SIBERIAN CRANES

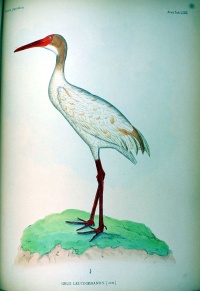

Siberian cranes (Grus leucogeranus) are beautiful, snowy white birds that reach a height of 1.25 meters (four feet) and have two meter (6.7 foot) wingspan. Often called “snow wreathes,” they have a bright red face and beak and black primary feathers on their wings,, Otherwise they are completely white. Regarded as the most specialized of cranes and the most endangered, Siberian cranes reside, nest and roost exclusively in bogs, marshes and wetlands. One reason for their severely endangered status is the shrinking of wetland habitats worldwide. [Source: George Archibald, National Geographic, May 1994]

Siberian cranes are majestic birds that have been described as poetry in motion because of their slow and deliberate movements and graceful mating dance. Their vocalizations are said to be flute-like with tones that float down to earth like music from the sky. Siberian cranes are the most far-ranging cranes. They migrate 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles) between their breeding ground in the Siberian Arctic and their wintering grounds in China and Iran. The journey of teh two populations passes through 11 countries and covers large distances over inhospitable terrain. The birds stop at wetlands along the way and call continuously when they fly.

The characteristic mating dances of Siberian cranes have inspired many cultures, who have incorporated some of the moves into their own dances. Images of these birds have dated to 6,000 years ago have been found on ancient cave walls. For the Yakut and Yukaghir people of northern Russia, white cranes are sacred birds associated with sun, spring and kind celestial spirits ajyy. In Yakut epics male and female Olonkho shamans transform into white cranes. Russians paid tribute to the crane’s loyalty with songs referring to the cranes as soldiers returning to their homeland. In the past they have been kept as pets. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

Siberian cranes live a long time. The world’s oldest living bird, according to the Guiness Book of World Records, is a Siberian crane named "Wolf" that died at the age of 82 at the International Crane Foundation facility in Wisconsin. Cranes have long been associated with longevity in China and Japan, where pictures and statues of cranes are displayed at weddings and birth ceremonies. They are symbols of health and prosperity and a life without war, therefore these birds are the symbol of peace. |=|

See Separate Article CRANES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Siberian Crane Habitat and Where They Are Found

Siberian cranes breed in the Arctic Russia and migrate south for the winter.There are two main populations of Siberian cranes: in western and eastern Russia. The eastern population migrates during winter from the Arctic tundra of eastern Russia to China while the western population migrates from Arctic tundra of western Russia and winters in Iran and formerly, in India and Nepal. Western Siberian cranes are on the verge of extinction. Only one of them was left in the wild as of 2010. See Migrations Below

The eastern population breeds between the Kolyma and Yana rivers and south to the Morma mountains. Non-breeding birds summer in Dauria, which embraces parts of China, Mongolia, and Russia. Main wintering sites are in the middle to lower reaches of the Yangtze river, Poyang Hu lake, China, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Western populations breeding in the Tyumen District, Russia and winter in Fereidoonkenar and Esbaran in Iran. There used to be a central population that bred on the basin of the Kunovat river in Russia and wintered in Keoladeo National Park, India. This population is now extinct. They are native to Asia. |=|

Siberian cranes nest and feed primarily in bogs, marshes, and other wetlands with wide expanses of shallow fresh water and good visibility. Their breeding areas are found mainly in lowland tundra, taiga/tundra transition, and taiga biogeographic regions. Their wintering areas are mainly in wetlands.

Siberian Crane Characteristics and Diet

Siberian cranes are thin, long birds. They range in weight from 4.9 to 8.6 kilograms grams (10.8 to 19 pounds) and range in length from 1.1 to 1.2 meters (3..5 to 4 feet). Their wingspan ranges from 2.1 to 2.3 meters (6.9 to 7.6 feet). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: The sexes look alike but males are larger. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Adults can be identified by their white plumage with the exception of the primaries, which are black. Located on the forecrown, forehead, face, and side of the head is a featherless cap which is brick red in color. Young cranes do not have this cap, instead they have feathers in that area and their plumage is cinnamon in color. The chicks eyes are blue at hatching, changing after about six months.

Adult Siberian cranes have reddish or pale yellow eye color and reddish-pink legs and toes. It is difficult to distinguish males from females because they are similar in appearance; however, males tend to be slightly larger than females. A unique characteristic is their serrated bill, which aids in catching slippery prey and assists with feeding on underground roots.

Siberian cranes are omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). They mainly feed on snails, roots, sedge tubers and insects. Other animal foods include fish, mollusks, terrestrial worms, frogs and occasional mammals . Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, roots and fruit such as cranberries. Siberian cranes forage during the early morning and afternoon, using their serrated bills to extract roots and tubers from wetland ponds. Siberian cranes are primarily herbivorous, but during the breeding season they eat more animal matter and fruits.

Siberian Crane Behavior

Siberian cranes fly and glides and are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), territorial (defend an area within the home range) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Their average territory size is 625 square kilometers. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Siberian cranes are somewhat social but less social that other crane social species. Family flocks are relatively small, made up of about 12 to 15 birds. Individuals are territorial during both breeding and winter seasons. They puff out their feathers and make loud calls to repel intruders. Males sometimes fight at their feeding spots. The fights are quick with the loser walking away, feigning indifference.

Siberian cranes are the most aquatic of cranes. They use wetlands for almost everything they do: feeding, nesting, rooting, and behavioral displays. Throughout the day they roost in shallow water, nest, preen, and attend to their young ones during breeding season. At night, Siberian cranes rest on one leg while the head is tucked under the shoulder. While roosting they remain separate from sarus crane groups (Grus antigone), which inhabit the same ponds. Sarus cranes are common at wintering areas and forage in habitats ranging from dry crop-lands to fairly deep water. Sarus cranes are larger, so often dominate the shallow foraging areas.

Siberian cranes are well-known for their dances, which they do at any time and with any available partner or by themselves. The dance includes leaping and bowing. The head and neck are brought forward from a fully vertical posture to a position with the neck and head reaching downward and backward between the legs. Although dancing is not directly connected with mating it can appear during the reproductive cycle as an expression of of excitement.

Siberian Crane Senses and Communication

Siberian cranes sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell and communicate with vision, sound and duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds). The voice of Siberian cranes has been described as melodious, yet peculiar. They have a flute-like voice. In contrast other cranes have a trumpet-like calls. Siberian cranes are more vocally active in the afternoon than in the morning, and their vocal activity may continue into the evening during roosting. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Vocalizations by Siberian cranes include: contact calls, stress calls, alarm calls, guard calls, flight-intention calls, food begging calls, location calls, as well as the unison call exhibited during courtship. These vocalizations are learned when they are fairly young and are important in social interactions among mating paisr and in groups. |=|

Vocalization is often accompanied by visual communication in the form of dancing. Certain calls are made with certain body movements. The unison call described below in the mating section is a good example of the connection between auditory and visual communication. Among the other forms of physical expression are tail fluttering, feather ruffling, preening of the back of the thighs, flapping, rigid strutting and threat postures, accompanied by hissing, growling, and stamping,

Siberian Crane Migrations

The main western Siberian crane migration routes have traditionally been: 1) from a summer breeding area around the Ob River near the Arctic Ocean and east of the Ural mountains and a wintering area at Keoladeo National Park in India, passing through Afghanistan and Pakistan along the way; 2) from a breeding area around Gorki Russia, just east of the Urals and just south of Arctic Ocean to a wintering area south of the Caspian Sea in Iran; and 3) from a summer breeding area in Chokurdakh in eastern Siberia near the Arctic Ocean to a wintering area at Poyang Lake in China.

Siberian cranes no longer migrate to India. They used to migrate 6,000 kilometers (3,400 miles) between Siberia and India, crossing the Himalayas and often attaining an elevation of up to 9,144 (30,000 feet) — the cruising altitude for commercial jets. Unlike many other birds cranes are not born with the instinct to fly their migrations paths. They have to be taught. They conserve energy by riding air currents for miles.

Scientists have trained Siberian cranes bred in captivity to fly to Iran rather than India, because there are less dangers on that route. World hang glider champion, Angelo d’Arrigo, has been involved in the program. The ultralights are basically hang gliders that have small motors which are used for take offs and situations in which there are no thermals to ride. The plan has been for the vast majority of the simulated migration flight to be done without the engine. Cranes were brought up with d’Arrigpo and his hang glider and were trained to follow it. Their journey was scheduled to take place over 40 days and 3,400 miles.

Siberian Crane Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Siberian cranes are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and mate for life and with males and females sharing nesting, foraging, incubating and child rearing duties. They engage in seasonal breeding. Siberian cranes breed once a year. Breeding occurs from May to August. The average number of eggs per season is two. Young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. Males and females both incubate eggs, protect, and feed their young. Males spend more time feeding the young than do females. The time to hatching ranges from 27 to 29 days, with the fledging age ranging from 70 to 75 days and the age in which they become independent ranges from eight to 10 months. Siberian cranes don’t breed until they are five to seven years old. In contrast other cranes begin breeding when they are three. [Source:Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Siberian crane pairs usually nest in bogs, marshes, and other wetlands. Courtship and pair bonding includes singing, known as unison calling, and dancing. Males and females fluff out their breast feathers and do a dance in the mating season. Females carefully preen their necks with mud as if it were make up. This means it is time to dance.

Catherine Bartnik wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Unison calling is a complex and extended series of coordinated calls. Males initiate calls by drawing their head and neck back into an S shape. They then rotate their neck downward and turn the bill toward the breast. They utter a high-pitched call while exposing the primaries, slowly turning the head until it is extended almost vertically. The neck is raised vertically during calls and lowered between calls. position of the neck is obtained with the head raised during calls and lowered between them. The wings are drooped during this time. The female joins in after the male has begun calling, holding her head upward and moving it up and down with each call in unison with the male. Rather than lifting their wings over the back, as do males, females keep them at their sides and folded. |=|

Parents generally incubate two eggs. Both eggs hatch but only one chick — the dominant hatchling — typically survives and is raised. Young Siberian cranes have brown heads and brown splotches on their wings and body. They grow an inch a day and imprint to their first care givers, even if they are humans. Parents teach their young to fly, find food and oil their feathers with a gland on their back to make them waterproof. Young cranes are born and spend just a short time in the Arctic summer before they have to make the journey south.

Endangered Siberia Cranes

Siberian cranes are the most endangered of the 15 species of crane. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Critically Endangered. They are protected under the US Migratory Bird Act. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants.[Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

There are estimated to be around 3,500 to 4000 of Siberian cranes, with 98 percent of them wintering at Poyang Lake in China, which is threatened by hydrological changes caused by the Three Gorges Dam and other water development projects. The western population had dwindled to four in 2002 and was thought to be extirpated but one individual was seen in Iran in 2010. The cranes that wintered in India are believed to be extinct. The number of them at Keoladea Ghana National Park in India declined from 200 in 1965 to five in 1998. There were nine in 1999. At that time six were seen in Iran. The Iran group is probably extinct now too. The last remaining flock winters in China. No other flocks are known.

Siberian cranes have been hurt by loss of habitat, mainly wetlands, caused by rapid development and deforestation, uncontrolled hunting and a lack of preservation effort to save them. Some cranes are believed to have been shot while flying over war-ravaged Afghanistan. Others have been brought down in Pakistan by hunters with rocks tied to twine. In Rajasthan, Indian in 1914, 4,000 birds were killed in a single day during a maharajahs hunting party.

In the past Siberian cranes have been hunted and trapped for food. The conversion of grasslands ro agriculture areas, dams and water diversion, urban expansion and land development, changes in vegetation, pollution and environmental contamination, and collision with utility lines have all negatively affected Siberian cranes. Direct exploitation through over-hunting, poaching, poisoning, and trapping has mostly stopped but played role in depleting populations in the past. Breeding and wintering grounds are in danger of being further disturbed or destroyed by human activity. [Source: Catherine Bartnik, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Siberian Crane Conservation

Measures have been taken to diminish certain threats by establishing sanctuaries and enforcing conservation laws. Young cranes have been successfully hatched and raised in captive breeding centers. Chicks are kept in visual and vocal isolation form their human keepers who feed them with hand puppets. Efforts to get adult cranes to teach captive bred youngsters to fly the route have failed.

Satellite telemetry was used to track the migration of the flock that wintered in Iran and it was observed that they rested on the eastern end of the Volga Delta. Satellite telemetry was also used to track the migration of the eastern population in the mid-1990s, leading to the discovery of new resting areas along the species' flyway in eastern Russia and China. Siberian cranes are one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies and is subject of the Memorandum of Understanding concerning Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane concluded under the Bonn Convention.

There have long been plans to raise Siberian crane chicks in captivity in Russia by people in crane costumes and train them to fly behind ultralight planes (motorized hang gliders) flown to their wintering areas. In autumn 2005, three ultralights were launched from Uvat, Russia and flew over western Kazakstan and stopped at the Volga River, Astrakhan nature Reserve and followed the Caspian Sea to crane wintering grounds in Iran. In September 2012, Russia's president Vladimir Putin piloted an ultralight over an Arctic wilderness while leading six endangered Siberian cranes at the beginning of their migration southward.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025