JAPANESE TEA CEREMONY

The tea ceremony, known in Japan as “chanoyo” or “sado”, is unique to Japan and one of country's most famous cultural traditions. It is an art form that incorporates various elements of Japanese culture such as Zen Buddhism, flower arrangement, ceramics, architecture, calligraphy, social etiquette and food. “Chanyo” means "way of the tea." The strict rules of tea ceremony etiquette, which at first glance may appear burdensome and meticulous, are in fact carefully calculated to achieve the highest possible economy of movement. When performed by a master they are a delight to watch. The tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) said, “The way of tea is just to boil water, make tea and only drink it...this you should know.”

On things to love about life in Japan, Andrew Bender wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Tea ceremony. Yes, there's tea involved, but that's only one part of it. In the tea ceremony (I prefer a direct translation of the Japanese word sado, the way of tea), the setup is as important as the action: fresh picked flower in the tokonoma, calligraphy scroll conveying a precise emotion, bowls and vases selected specificly for the season. It's all about making the most of this one moment — it sounds very Zen, and in this case that's not a cliché. [Source: Andrew Bender, Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2012]

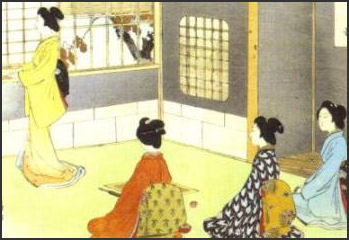

The tea ceremony is the ritualized preparation and serving of powdered green tea in the presence of guests. A full-length formal tea ceremony involves a meal (“ chakaiseki”) and two servings of tea (“ koicha “and “ usucha”) and lasts approximately four hours, during which the host engages his whole being in the creation of an occasion designed to bring aesthetic, intellectual, and physical enjoyment and peace of mind to the guests. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“To achieve this, the tea host or hostess may spend decades mastering not only the measured procedures for serving tea in front of guests, but also learning to appreciate art, crafts, poetry, and calligraphy; learning to arrange flowers, cook, and care for a garden; and at the same time instilling in himself or herself grace, selflessness, and attentiveness to the needs of others. Though all efforts of the host are directed towards the enjoyment of the participants, this is not to say that the Way of Tea is a selfindulgent pastime for guests.

“The ceremony is equally designed to humble participants by focusing attention both on the profound beauty of the simplest aspects of nature’such as light, the sound of water, and the glow of a charcoal fire (all emphasized in the rustic tea hut setting) — and on the creative force of the universe as manifested through human endeavor, for example in the crafting of beautiful objects. Conversation in the tearoom is focused on these subjects. The guests will not engage in small talk or gossip, but limit their tea ceremony conversation to a discussion of the origin of utensils and praise for the beauty of natural manifestations.

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Formal Tea Gathering japanesegardening.org ; Japanese Tea Ceremony apanese-tea-ceremony.net ; Essay Evolution of the Tea Ceremony on aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Rituals and Symbolism of the Tea Ceremony aabss.org/journal1999 ; Anthropological Look at the Japanese Tea Ceremony humnet.ucla.edu ; Sally’s Place Glimpse at Chanoyu sallybernstein.com ; Teanobi teanobi.com ; Brief Description holymtn.com/tea ; Another Brief Description markun.cs.shinshu-u.ac ; ; Urasenke Tradition of Tea in Washington D.C, urasenkedc.org ; Urasenke School Urasenke . Ogasawara Sencha Service School Ogasawara Tea ceremony for English speakers in Tokyo JNTO ; Tea ceremony in Kyoto Kyoto Travel Guide ; Books: “The Japanese Way of Tea” by Sen Soshitsu (University of Hawaii, 1999); “The Book of Tea” by Okakura Akuzo (Dover, 1964).

Flower Arranging Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Ikebana International Ikebana International ; Ikenobo ikenobo.jp ; Ikebana Links users.telenet.be/ikebana ; Flower arranging classes in Tokyo JNTO

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEA CEREMONY AND FLOWER ARRANGING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Tea Ceremony Tea

“Matcha” is high quality powdered green tea used in the tea ceremony. Tea varieties have different tastes that are determined by different cultivation methods, picking seasons, sections of the tea leaves used, and production processes. “Sencha” is regular green tea. The most widely consumed tea in Japan, it has a balanced stringent, bittersweet taste and made using steamed leaves to maintain a bright green color. Gyokuro is high quality tea made from the finest new leaves carefully protected from direct sunlight. It has a sweet and mellow taste.

Tea was introduced to Japan from China around the 8th century. Buddhist monks introduced matcha (green tea) for medicinal purposes in the 12th century. Even today Zen monk extol Japanese tea as a "most wonderful medicine" and "the secret of long life."

Objective of the Tea Ceremony

tea house The objective of the tea ceremony is to purify the soul by becoming one with nature through a ritual that pays homage calmness, gracefulness, balance, harmony, purity and the "aesthetic of austere simplicity and refined poverty." Some also regard it as an effort to boost endurance and build a strong spirit. This contrasts with the Chinese perception of tea drinking which is associated with the martial arts and relaxing. The great 20th century tea master Hounsai Soshitsu Sen said, "In tea, we purify things we can see and seek catharsis in the process. This way, the sense that one is being healed returns. The host and the guests at the tea gathering share in that feeling, which we call 'Ichigo, ichie.' Roughly translated, this Zen axiom means 'One lifetime, one chance.'"

The objective of a tea gathering is that of Zen Buddhism — to live in this moment — and the entire ritual is designed to focus the senses so that one is totally involved in the occasion and not distracted by mundane thoughts. People may wonder if a full-length formal tea ceremony is something that Japanese do at home regularly for relaxation. This is not the case. It is rare in Japan now that a person has the luxury of owning a tea house or the motivation to entertain in one. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Entertaining with the tea ritual has always been, with the exception of the Buddhist priesthood, the privilege of the elite. However, ask if there are many people in Japan who study the Way of Tea, and the answer is yes, there are millions — men belonging to a hundred or more different tea persuasions in every corner of Japan. Every week, all year round, they go to their teacher for two hours at a time, sharing their class with three or four others. Each takes turns preparing tea and playing the role of a guest. Then they go home and come again the following week to do the same, many for their whole lives.

“In the process, the tea student learns not only how to make tea, but also how to make the perfect charcoal fire; how to look after utensils and prepare the powdered tea; how to appreciate art, poetry, pottery, lacquerware, wood craftsmanship, and gardens; and how to recognize all the wild flowers and in which season they bloom. They learn how to deport themselves in a “ tatami “(reed mat) room and to always think of others first. The teacher discourages learning from a book and makes sure all movements are learned with the body and not with the brain. The traditional arts — tea, calligraphy, flower arranging, and the martial arts — were all originally taught without texts or manuals.

Philosophy and Metaphysics of the Tea Ceremony

The goal is not the intellectual grasp of a subject, but the attainment of presence of mind. Each week there are slight variations in the routine, dictated by the utensils and the season, to guard against students becoming complacent in their practice. The student is reminded that the Way of Tea is not a course of study that has to be finished, but life itself. There are frequent opportunities for students to attend tea gatherings, but it does not matter if the student never goes to a formal four-hour “ chaji” — the culmination of all they have learned — because it is the process of learning that counts: the tiny accumulation of knowledge, the gradual fine-tuning of the sensibilities, and the small but satisfying improvements in the ability to cope gracefully with the little dramas of the everyday world. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The power of the tea ritual lies in the unfurling of self-realization. After being imported from China, green tea came to be drunk in monasteries and the mansions of the aristocracy and ruling warrior elite from about the 12th century. Tea was first drunk as a form of medicine and was imbibed in the monasteries as a means of keeping awake during meditation. Early forms of the tea ceremony were largely occasions for the ostentatious display of precious utensils in grand halls or for noisy parties in which the participants guessed the origins of different teas.

Early History of Tea in Japan

Tea was consumed as far back as the 7th century by meditating Buddhist monks to stay alert. Historical records report tea being given to Emperor Saga by a priest who has returned from China in A.D. 815. By the 14th century tea drinking had developed in an elaborate and expensive pastime enjoyed by the upper classes. There are some tea plants native to Japan but nobody ever thought of drinking tea made from their leaves until after tea was introduced to Japan from China.

According to legend, tea was created 1,300 years ago by an Buddhist monk with bushy eyebrows, named Bodhidharma, who mediated for nine years by staring at the wall of a cave. To battle his occasional bouts of drowsiness, he drank tea and came up with the novel idea of cutting off his eyelids so his eyes wouldn't close. On the place where he placed his severed eyelids, the first tea bushes appeared. This is reportedly why tea and the tea ceremony are so important to Zen Buddhism and Japanese culture as a whole.

Some trace the tea ceremony back to the 12th century when Abbot Yoisai (also known as Eisai, 1141-1215) introduced to Japan a new method for making powdered green tea. A member of the Rinzai school of Zen, he is said to have brought back tea seeds from tea bushes from China and planted them at his temple. At that time tea had a number of health benefits ascribed ti it in China and was used to harmonize different parts of the body.

Japanese Tea Rooms

In the Ashikaga Period (1338-1573), the Japanese upper classes considered it a pleasure to sit in a quite room with friends, separated from the worries of life, and listen to the soft sound of water boiling. Members of the aristocracy created special tea rooms in their palaces or tea houses in their gardens that looked simple in appearance but were actually created with a careful eye for detail. Daimyo held important meetings in tea houses that were set up to display their wealth.

tea room

The idea of the traditional tea ceremony cottage was to create an atmosphere of calm and meditation. Tea cottage designed by the great 15th century architect Senno Rikyu (1522-1591) were small and contained a bamboo ceiling, bare walls, sliding doors covered with snow-white translucent Japanese paper, and pillars made with wood still containing their bark. The only adornment was a hanging scroll will calligraphy or a flower arrangement in the “tokonoma”, an alcove in a traditional Japanese home intended for displaying a flowers or art.

The goal was to create a facsimile of a hermit's hut with a sense of “wabi” (quiet taste) and “shibumi” (sobriety). Hedges, stepping stones, a hand-washing basin and stone lanterns were placed on path to prepare one's spirit for the ceremony.

History of Tea Ceremony in Japan

Eisai taught early practitioners of Zen to drink tea before the mediated to purify their mind and relax and said the attainment of enlightenment itself could be easier with tea. Eisai is said to have planted many tea seeds. Many of the tea bushes in Kyoto, Fukuoka and Saga Prefectures are said to have originated from seeds brought back by Eisai from China.

The true tea ceremony was devised by Murata Juko (died 1490), an advisor to the Shogun Ashikaga. Juko believed one of the greatest pleasures in life was to live like a hermit in harmony with nature, and he created the tea ceremony to evoke this pleasure. The tea ceremony was influenced by samurai culture and Zen Buddhism, both of which emphasized discipline and simplicity. The tea ceremony was an important aspect of a samurai's training. Samurai class developed certain rules and procedures that participants of the tea ceremony were supposed to follow.

The form of tea ceremony practiced today was created in the late 1500s by the tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). He served as tea master for Hideyoshi Toyotomi and is credited with simplifying the tea ceremony in accordance with Zen ethos and the concept of wabi (simplicity) and bringing the tea ceremony from the upper classes to ordinary people. He replaced Chinese porcelain with hand-molded Japanese ceramics formalized the austere aesthetic and emphasized the use simple tools that reflected the unpredictable aspects of nature. Rikyu died after committing ritual suicide for reasons that are still mysterious.

Momoyama period tea ceremony wasn’t all austerity. Rikyu’s protégé and successor, Furuta Oribe (1543-1615), preserved the wabi style but also experimented with it. Ceramics created under his tutelage were strangely formed and colored with greens and yellows. Pieces that were cracked and had odd asymmetrical shapes were greatly prized. Others were shaped like pinwheels and flowers. He too died by his own sword on the command of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Tea Ceremony Schools

Through the influence of Zen Buddhist masters of the 14th and 15th centuries, the procedures for the serving of tea in front of guests were developed into the spiritually uplifting form in which millions of students practice the Way of Tea in different schools today. One 15th-century Zen master in particular — Murata Juko (1422--1502) — broke all convention to perform the tea ritual for an aristocratic audience in a humble four-and-a-half-mat room. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

There are 10 major tea ceremony schools with 5 million followers nationwide. The details of each school vary slightly and may be different from the description provides here. There are three main Senke schools, inspired by Sen ni Rikkyu: Ura, Omete and Muskakoji. Other influential schools include Enshu, Yabunouch and Sohen. To be able to present the tea ceremony one has to take a three-year course. After graduating one receives a licence and tea name.

The largest of all the tea schools today are Urasenke and Omotesenke, founded by two of Rikyu’s great-grandsons. Under their influence and that of certain other major schools, the Way of Tea is now being taught around the world, while in Japan both men and women are reappraising the value of the Way of Tea as a valuable system for attaining mastery of life.

The great 20th century tea master Hounsai Soshitsu Sen was the 15th grand master of the Urasenke school of tea ceremony. He has traveled to 62 countries on more than 300 occasions to promote world peace. He took this calling after World War II in which he was trained as a Kamikaze pilot.

The Urakuryu school of tea ceremony is sometimes referred to a the samurai-style tea school. It was founded by Oda Urakusai, the younger brother of Oda Nobunaga, a 16th century warlord and one of Japan’s most well known historical figures. Among its practitioners were members of the Tokugawa family, one of the most important ruling Japanese families. Among the school’s customs are placing the “ fukusa “, a small silk cloth used to wipe utensils, in the right side of the obi. Most schools place it in the left side. The Urakuryu school place it in the right side because samurai kept their swords in the left side.

Tea Ceremony Great Masters

Sen no Rikyu “The tea master who perfected the ritual was Sen no Rikyu (1522--1591). Rikyu was the son of a rich merchant in Sakai, near Osaka, the most prosperous trading port in Japan in the 16th century. His background brought him into contact with the tea ceremonies of the rich, but he became more interested in the way priests approached the tea ritual as an embodiment of Zen principles for appreciating the sacred in everyday life. Taking a cue from Juko’s example, Rikyu stripped everything non-essential from the tearoom and the style of preparation, and developed a tea ritual in which there was no wasted movement and no object that was superfluous. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Instead of using expensive imported vessels in a lavish reception hall, he made tea in a thatched hut using only a simple iron kettle, a plain lacquered container for tea, a tea scoop and whisk whittled from bamboo, and a common rice bowl for drinking the tea. The only decoration in a Rikyu-style tearoom is a hanging scroll or a vase of flowers placed in the alcove. Owing to the very lack of decoration, participants become more aware of details and are awakened to the simple beauty around them and to themselves.

“The central essense of Rikyu’s tea ceremony was the concept of “ wabi”. “ Wabi “literally means “desolation.” Zen philosophy the gathering and to tea ceremony takes the positive side of this and says that the greatest wealth is found in desolation and poverty, because we look inside ourselves and find true spiritual wealth there when we have no attachments to things material. His style of tea is thus called “ wabi-cha”. After Rikyu’s death, his grandson and later three great-grandsons carried on the Rikyu style of tea.

“Meanwhile, variations on “ wabi-cha “grew up under the influence of certain “ samurai “lords, whose elevated status required them to employ more sophisticated accoutrements and more elaborate manners and procedures than the simple “ wabi-cha”. New schools developed, but the “ wabi-cha “spirit can be said to be central to all. When the warrior class was abolished in Japan’s modern era (beginning in 1868), women became the main practitioners of tea. The tea ceremony was something that every young woman was required to study to cultivate fine manners and aesthetic appreciation. At the same time, political and business leaders and art collectors used tea as a vehicle for collecting and enjoying fine art and crafts.

Proper Full Length Tea Ceremony

At a full-length formal tea ceremony (“ chaji”), the guests first gather in a waiting room where they are served a cup of the hot water that will be used for making tea later on. They then proceed to an arbor in the garden and wait to be greeted by the host. This takes the form of a silent bow at the inner gate. Guests then proceed to a stone wash basin where they purify their hands and mouths with water and enter the tearoom through a low entrance, designed to remind them that all are equal. Guests admire the hanging scroll in the alcove, which is usually the calligraphy of a Zen Buddhist priest, and take their seats, kneeling on the “ tatami “(reed mat) floor. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“After the prescribed greetings, the host adds charcoal to the fire and serves a simple meal of seasonal foods, just enough to take away the pangs of hunger. This is followed by moist sweets. Guests then return to the arbor and wait to be called again for the serving of tea. The tea container, tea scoop, and tea bowl are wiped in a symbolic purification, the rhythmic motions of which put the guests into a state of focused calm. Tea of a thick consistency is prepared in silence and one bowl of tea is passed between guests, who drink from the same place on the bowl in a symbolic bonding.

“The host then adds more charcoal to the fire, serves dry sweets, and prepares tea of a thinner, frothier consistency. During this final phase the atmosphere lightens and guests engage in casual conversation. However, talk is still focused on appreciation of utensils and the mood. It is the main guest’s duty to act as a representative of all those present and ask questions about each of the utensils and decorations chosen for the gathering and to work in unison with the host to ensure that the gathering proceeds perfectly, with nothing to distract the guests from their inspiration.

“The guest carries a packet of folded papers on which sweets should be placed before eating. A special cake pick is used to cut and eat moist sweets but dry sweets are eaten with the fingers.

Setting for the Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony is best held in a simple, beautiful, austere tea room or cottage, with little furniture in the inner part of a garden. There are two rooms. One is the guest room or tea room. The other is the anteroom used by the host. Everything has a time, place and reason.

The ritual begins before one even enters the door. As the guests enter the garden they see a waiting ardor. Here all the guests meet before they enter the tearoom. A narrow path paved with stepping stones leads through the garden and connects the arbor to the tea room.

Bennet Schiff wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "the path through a garden to the tea house is irregular. It is not a path you can get to along a plumb line. Each selected stone on the path is to be appreciated, as is the garden itself: the waterfall, the carp as they perform light-struck shadowy arabesques in the pond." [Source: Bennet Schiff, Smithsonian magazine, November 1988]

When the guests are ready to be received, they are welcomed by the host, sometimes with a few strikes to a gong. The guests then proceed towards the tea room, after rinsing their mouths and hands in a stone basis that sits by the side of the path. The host comes out about halfway to meet them.

The spare, bare little tea house is entered through a door about three feet high or a hole in a large door. When arriving for the tea ceremony you are supposed enter on you hands and knees to show humility and are expected to admire the flowers in the tokonama niche.

Tea Ceremony Master

A proper tea ceremony is led by a tea master. The tea master Hounsai Soshitsu Sen of the Urasenk Tea School was the son of a tea master. He began his training at the age of six and became a grand teas master at the age of 41 when his father died.

Sen told the Daily Yomiuri, "Having stood back and watched my father all those years, I was naturally ready to follow in his footsteps...We still need to practice hundreds, even thousands, or more than other people, and learn to live with embarrassing mistakes, in order to be better than our fathers." Sen said that he never touches coffee. "I like its aroma," he said. "But as a grand tea master, I can't allow myself to give in to temptation."

Late Zen master Taiki Tachibana, a prominent figure in Buddhist circles in Kyoto, reportedly told Konosuke Matsushita, the late founder of home appliance giant Panasonic Corp., to his face: "Because of you, Japan has become an awful place [with people] losing their compassion and only seeking material gratification. This must be corrected under your responsibility." The absence of compassion was something the widely revered Taiki deplored.

This episode was recounted in the book "Cha no yu gatari, hito gatari" (stories of tea ceremonies and people) written by then Hakuhodo Inc. President Michitaka Kondo, who was present at the tea ceremony in the autumn of 1975. In the book, published by Tankosha Publishing Co., Kondo recalled that Matsushita remained amiable and appeared to be deep in thought after this rebuke. Four years later, Matsushita founded the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management to nurture human resources with the skills to manage state affairs. Yoshihiko Noda, 54, who later became Japan’s prime minister, was in the institute's inaugural class.

Tea Ceremony Posture and Movements

In the traditional tea ceremony every movement is graceful and understated and carried out according with highly stylized etiquette. Newcomers often find the process tedious and uncomfortable. Connoisseurs insist it takes years of practice and training to fully appreciate and decades to learn all the responsibilities of the tea master.

Tea ceremony participants are expected to sit with their backs straight, their feet tucked under their butts a precise distance from the edge of the tatami mat, with their eyes caste downward. To the uninitiated this position can be uncomfortable for short period and torture if held for 15 minutes or more.

The participants are encouraged to relax and meditate on their surroundings and the craftsmanship of the tea utensils. Sometimes small cakes, sweets or snacks are offered to guests. These are eaten before tea with a pick-like utensils called a “kuromoji” are designed to encourage reflecting upon the seasons.

Tea Ceremony Objects

Object used in the tea ceremony included special porcelain or ceramic bowls, a cast-iron kettle with bronze lid, freshwater water jars, ceramic of lacquer container for powdered tea, and tea caddies. There are four main principals defining the way people and tea objects interact: “wa” (harmony); “kei” (respect); “sei” (purity) and “jyaku” (tranquility).

Smithsonian curator for ceramics Louise Allison Cort wrote, the tea ceremony "played a special role in the development of distinctive Japanese view of materials. The host preparing to make tea assembled a group of utensils made of disparate but complementary materials...Juxtaposition and contrast of the materials within the compact space emphasized their distinctive qualities."

Within the tea ceremony "there developed the singular Japanese appreciation for tea bowls, vases and water jars made of unglazed stoneware clay — material relegated yo utilitarian purposes elsewhere in the world. Terms such as "chilled" and "withered' were used to describe the emotional response to the wood-fired clay surface."

Since the 16th century, crafts, regarded as great works of art, have been created for the tea ceremony. These crafts have provided work for generations of highly-skilled craftsmen and workshops. It is not unusual for connoisseurs to shell out tens of thousands of dollars for a perfectly-made modern tea ceremony bowl and hundreds of thousands of dollars for a classic piece.

Tea Ceremony Tea Drinking

The key elements of the tea ceremony include: 1) measuring of powdered green tea into a bowl with a bamboo spoon; 2) poring the water with a ladle dipped in a kettle heated over a charcoal fire; 3) whisking of the tea into a creamy foam with a bamboo whisk; 4) serving the guests one at a time in formal movements; and 5) turning the cup to admire the beauty and texture of the tea before you drink it. After the tea is prepared it is passed down the line to drinkers. Monks traditionally cup the bowl in their hands while kneeling and drink the hot liquid in three slow swallows.

“When you receive a bowl of tea, place it between you and the next guest and bow to excuse yourself for going first. Then put it in front of your knees and thank the host for the tea. Pick the bowl up, put it in the palm of the left hand and raise it slightly with a bow of the head in thanks. Turn the bowl so that the front, distinguished by a kiln mark or decoration, is away from the lips. Drink and wipe the place you drank from with your fingers. Turn the front of the bowl back to face you. Put the bowl down on the “tatami” in front of you and with your elbows above your knees pick up the bowl and admire it. When returning the bowl, ensure that the front is turned back to face the host.

Michelle Green, who attended a tea ceremony as a tourist, wrote in the New York Times, “We kneeled facing one another across an enormous kettle on a brazier. Like a priestess, Ms. Fujii drew a small kit from the front of her kimono and extracted a bit of silk in which she purified the lacquerware tea container, the long-handed bamboo spoon, the spider-like whisk.”

“With a shallow spoon, Ms. Fuji tapped green matcha into a bowl selected for its quiet beauty. A stream of boiling water turned the powder into a pea-colored liquid that she whisked into a froth. Fast, then slower, in a prescribed motion; only the right hand, never the left. She issued invitations and cued my responses as they were lines in a play...As I held the bowl of tea that she had made for me and drank deeply, my teacher remained silent so I could take in the sharp fragrance and the creamy, bitter taste,” When its over one bows.

There are many variations. At Kenninji Temple in Kyoto, the home temple of Eisai, four monks each carrying serving trays with eight tea bowls and sweets, serve 32 guest seated around the perimeter of a room and a monk goes around and pours hot water in each bowl. This method was traditionally used to serve high-ranking priests, aristocrats who were seated according to their rank and status. In Nara there is a tea ceremony in which people drink the tea from huge punch-bowl-size bowls that they lift up to their mouths with two hands.

Image Sources: 1) Diagram and illustrations, JNTO and Asian Art Mall; 2) pictures, Japan Zone (tea, Rikyu , Wikipedia (1st photo) , Ray Kinnane (tea house) , Nicolas Delerue (Flower arranging)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013