CAPITALISM AND THE DEVELOPING WORLD

![]()

World Bank symbol The combined wealth of the three richest people — Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and Carlos Sims — is equal to the combined GNP of the world's 26 poorest countries.

In a 2009 GloboScan-BBC survey in 27 countries, more than a quarter of the people that responded said that capitalism was fatally flawed and a new economic system was needed. Only 11 percent of the 29,000 people surveyed said they believed capitalism worked well and did not think greater regulation was needed, About half said the problems of capitalism could be addressed with regulation and reform.

Washington Consensus Versus Beijing Consensus

Some refer to the Chinese economic model of relying on a strong authoritarian government to guide economic policy, allowing free markets but clamping down on human rights, as the Beijing Consensus. Cui Zhiyuan, a professor of public policy at Tsinghua University, told the Washington Post , “It is very possible that Beijing Consensus can replace the Washington Consensus — which emphasizes free trade, civilization, and prudent fiscal policy. Since the economic crisis the world doesn’t have as much confidence in the U.S. economic model as before.”

Ramesh Thakur wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Some countries have been trying to replace the Washington Consensus of free-market, deregulation, privatization, pro-trade and globalization policies with a Beijing Consensus of one-party, state-guided development, strictly controlled capital markets and an authoritarian decision-making process that can make tough strategic choices and long-term investments without being distracted by daily polls.[Source: Ramesh Thakur, Daily Yomiuri, November 26, 2010]

Columnist Anatole Kaletsky wrote in the Times of London that a leading U.S. diplomat told him that since the economic crisis in the late 2000s “developing countries have lost interest in the old Washington consensus that promoted democracy and liberal economics. Wherever I go in the world, governments and business leaders talk about the new Beijing consensus — the Chinese route to prosperity and power, The West must come up with a new model of capitalism that’s consistent with our political values. Either we reinvent ourselves or we will lose.”

The model of the Beijing Consensus is less painful for struggling economies in the developing world than the “shock therapy” prescribed by the IMF and Washington. It calls for gradual reforms, opening up to foreign trade while remaining self reliant and economic reforms having precedence over political reforms.

Barry Sautman, a political scientist at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, told the Washington Post, the Beijing Consensus “takes seriously the aspirations of developing states often ignored or opposed in the West” such as “a more equitable international distribution of wealth and power.”

There has even been mentions of a Seoul Consensus, raised when South Korea hosted the G-20 meeting in November 2010, which shifts the spotlight away from foreign aid toward investments in infrastructure, education, health, technology and manufacturing. The Seoul Consensus puts the emphasis on private sector-led, poverty-reducing economic growth and job creation that is inclusive, sustainable, resilient and balanced.

Calls to Reform the International Financial System

Moises Naim wrote in the Washington Post, “After every global financial crash — such as the Mexican peso crisis of 1994 and the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s — world leaders would gather at summits and pledge to drastically reform the international financial system to ensure that no more crises would occur. The need for “a new international financial architecture” became a frequent mantra. Typically, however, once the sense of emergency passed and struggling economies began to recover, the costs and complications of overhauling the international financial system became apparent — and the political will to undertake major reforms evaporated. [Source: Moises Naim, Washington Post, April 8, 2011. Naim, a former executive director of the World Bank, is a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace]

In recognition of this reality, calls for a new financial architecture following the great recession of 2008 have been replaced with more modest promises to modernize the “plumbing” of the financial system: to tighten banking regulations, revise accounting standards, examine the role of hedge funds and credit rating agencies, and other such measures.

These things are very important — but also very boring. Recruiting idealistic young activists to march against Basel III (as the new global regulatory standards for banks’ capital adequacy, adopted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, are known) is surely far more difficult than finding college kids willing to march in favor of debt relief for poor countries.

Globalization

World Bank building entrance Globalization and free trade have been touted by some as the best anti-poverty measure ever invented. Others claim they are intrinsically evil, primarily benefitting the developed countries at the expense of the developing ones in a way that is not all that different from old-fashioned imperialism.

In some places, particularly in China. factories, employees and workers have dramatically improved their standard of living and the once moribund economies have blossomed as a result of globalization and trade. Columbia economists Jeffrey Sachs wrote: “Globalization, more than anything else, has reduced the numbers of extreme poor in India by 200 million and in China by 300 million since 1990. Far from being exploited by multinational companies, these countries and many others like them have achieved unprecedented rates of growth on the basis of foreign direct investments and the export-led growth that followed.”

In other places, companies from rich countries have exploited resources like oil, gold, timber, coffee and bananas and degraded the environment and produced mostly low-paying menial and sweat shop jobs, giving the best jobs to non-locals.

According to a 168-page report by the World Commission on the Social Dimensions of Globalization, put together with the help of the presidents of Finland and Tanzania, “There is a missing link in today’s globalization between opportunities and access to opportunities.” The report said that the most vivid illustration of this is the widening income gap between the richest and poorest countries. In the 1960s the per capita income was $212 for the world’s poorest countries and $11,417 for the world’s richest countries. In 2002 the per capita income had only risen to $267 for the world’s poorest countries while it rose to $32,339 for the world’s richest countries.

See Trade

State-Capitalism and the Myth of Free Trade

In response to arguments by Stefan Halper in his book “The Beijing Consensus: How China’s Authoritarian Model Will Dominate the Twenty-First Century” and Ian Bremmer in his book “Uprising: Will Emerging Markets Shape or Skae the World Economy” that China unfairly uses “state-driven capitalism” as opposed to playing by the rules of free markets to gain an a competitive edge, John Cassidy persuasively argues in a New Yorker article that China is far from the first to do this.

In an article entitled Enter the Dragon in the December 12, 2010 issue of The New Yorker Cassidy wrote: “From Lord Palmerston to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Western officials have long demanded that countries open their domestic markets to foreign competition. But Britain and the United States embraced free trade as an ideal only after they had built up manufacturing industries that could dominate those of foreign rivals? In 1721, the [British] government of Robert Walpole placed a range of tariffs on all manufactured imports, erecting a protective wall around businesses that created the Industrial Revolution. A century later, while the heirs of Adam Smith were expounding the theoretical virtues of free trade, Britain retained some of the highest import tariffs in the world: more than fifty percent on many manufactured goods. [Source: John Cassidy, The New Yorker, December 13, 2010]

“Those levies stayed high until the eighteen-sixties, when the country’s competitive advantage in textiles, steel and other industries was firmly established. As the late economic historia Paul bairoch stressed, the idea that Britain rose to economic dominance through free trade is nonsense...The same is true of the United States? During the War of 1812, which was precipitated in part by trade disputes, [Congress] doubled import duties on manufactured goods, to twenty-five per cent. A few years later, the levies were raised to an average of forty per cent. Then Abraham Lincoln raised them again, to roughly fifty percent. [Ibid]

Ha-Joon Chang, an economist at the University of Cambridge, has observed that Lincoln, revered as the Great Emancipator, “might have equally be labeled the great protector — of American manufacturing.” Cassidy wrote: “During the half century after Lincoln’s presidency, the business-backed republican part was in power for most of the time, and tariffs on manufactured goods remained at forty to fifty per cent, the highest levels anywhere. It was during these years that the U.S. economy grew to rival the economies of Britain and Germany in industries such as iron and steel and chemicals — all of which benefitted from protection.” [Ibid]

Many have given credit to Japan, followed by South Korea and Taiwan, for pioneering the model of protecting industries and agriculture at home while developing an exports to spur raid economic growth. But as Ha-Joon Chang points out in Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (2008), “Policies that many believe, as I myself used, to have been invented by Japanese policy-makers in the 1950s...were actually early British inventions.”

Cassidy goes on to talk about how protectionism still exists in the U.S. in many industries, most notably in the form of agriculture subsidies. He also shows some of the recent fruits of these American protectionist policies; to again use the most notable example, the internet was a product of the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Cassidy ends the article by saying: “Unfortunately, in policy circles — and among much of the general public — the old mantras about the free market and private enterprises continue to dominate. In seeking to broaden access to private health insurance, the Obama administration was accused of plotting a takeover of the entire health-care industry. In cutting taxes and boosting federal spending to avert a depression, it was accused of embracing socialism. Even supposedly serious economists lend support to these views, arguing that the dysfunctional health-care industry is best left to its own devices, or that the eight-hundred-billion dollar stimulus program has had virtually no impact on jobs and on G.D.P. This is what comes of forgetting the critical role that states have played in nurturing, protecting, and financing their industries, as well as in taxing and taming them. The greatest danger that Western prosperity now faces isn’t posed by any Beijng consensus; it’s posed by the myth of the free market.”

Double Standards of Globalization

Ryo Takahashi wrote in the Japan Times, “One aspect of the globalized world today is that the world has plunged into fast-paced, turbulent times where everyone is connected — so much so that British sociologist Anthony Giddens has been compelled to write of today's age as one where "the local and the global are inextricably intertwined." [Source: Ryo Takahashi, Japan Times, 23, 2010. Takahashi is a Tokyo-based freelance writer and is the founder of Japan Commentator. He currently attends the University of Tokyo]

The fetters to a more egalitarian world order, as Joseph Stiglitz, former chief economist for the World Bank has observed in his book "Globalization and its Discontents," is that many international institutions have formulated policies in favor of developed countries at the expense of developing nations still mired in poverty. These kind of policies lead to conspicuous macro-inequalities such as the "North-South problem."

The North-South problem, the stark gap in living standards between the haves and have-nots in the Northern and Southern hemisphere, underscores the lopsided rules of the world economy. Of course, developed countries don't necessarily impose unfair trade rules out of villainous intent: Many have simply dug their heels firmly into the ground to maintain employment at home.

Employment in developed countries is often maintained through the use of protective barriers such as tariffs and subsidies. This helps to keep what would otherwise be unprofitable industries, in particular industries that are labor-intensive, lucrative.

Unfortunately, the double standard followed by developed countries — namely, defending trade protectionism for themselves and imposing trade liberalization abroad — leads all too often to developing countries becoming little more than markets for developed countries. Without fairer trade terms, it remains despairingly difficult for developing countries to achieve true economic independence.

The disparities in income between developed countries and developing countries cannot be amended while international policies remain largely unequal. Although institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have begun to bring poverty reduction to the fore, there is still much room for improvement. Of course, when it comes to international policymaking, it would be wrong for any one party to claim the moral high ground, but any nonpartisan would still be able to see that the rules of today's world economy continue to favor a select few countries.

Whether globalization is a force that brings about a more egalitarian world order or a force that exacerbates inequality remains to be seen. Critiquing something as broad in scope, and as obfuscating, as globalization is a daunting task, but there are two things that can be said with some degree of certainty: (1) Technological advances increase globalization's potential to act as a force that can greatly improve people's living standards, as was exemplified earlier by the ability of citizens to exercise their freedom of expression on equal terms over the Internet. (2) Global governance mandated by international institutions needs a dramatic overhaul so that more people can enjoy the benefits of international communication and world trade.Globalization has opened the door to a more egalitarian world order; whether we all step through the door is entirely up to us.

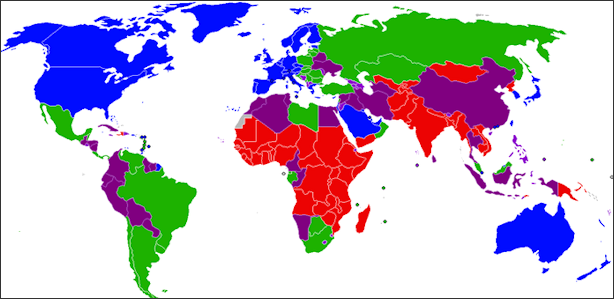

World Bank income groups

Global Inequality

The Economist reported in January 2011: “Globally, the gap between the rich and the poor has actually been narrowing, as poorer countries are growing faster. Nor is there a monolithic trend within countries (see article). In Latin America, long home to the world’s most unequal societies, many countries — including the biggest, Brazil — have become a bit more equal, as governments have boosted the incomes of the poor with fast growth and an overhaul of public spending to improve the social safety-net (but not by raising tax rates for the rich). [Source: The Economist, January 20, 2011]

The gap between rich and poor has risen in other emerging economies (notably China and India) as well as in many rich countries (especially America, but also in places with a reputation for being more egalitarian, such as Germany). But the reasons for this differ. In China inequality has a lot to do with the hukou system of residency permits, which limits internal migration to the towns; by some measures inequality has peaked as rural labour becomes more scarce. In America income inequality began to widen in the 1980s largely because the poor fell behind those in the middle. More recently, the shift has been overwhelmingly due to a rise in the share of income going to the very top — the highest 1 percent of earners and above — particularly those working in the financial sector. Many Americans are seeing their living standards stagnate, but the gap between most of them has not changed all that much.

These nuances suggest that rather than fretting about inequality itself, policymakers need to differentiate between its causes and focus on ways to increase social mobility. A global market offers far bigger returns to those at the top of their game, be they authors, lawyers or fund managers. Modern technology favours the skilled. These economic changes are themselves often reinforced by social ones: educated men now tend to marry educated women. The result of all this, as our special report this week shows, is the rise of a global elite.

At heart, this is a meritocratic process; but not always. Rules and institutions are often rigged in ways that limit competition and favour insiders at the expense both of growth and equality. The rules can be blatantly unfair: witness China’s limits to migration, which keep the poor in the countryside. Or they can involve more subtle distortions: look at the way that powerful teachers’ unions have stopped poorer Americans getting a good education, or the implicit “too big to fail” system that encouraged bankers to be reckless and left the rest with the tab. These are very different problems, but they all lead to wider inequality, fewer rungs in the ladder and lower growth.

Viewed from this perspective, the right way to combat inequality and increase mobility is clear. First, governments need to keep their focus on pushing up the bottom and middle rather than dragging down the top: investing in (and removing barriers to) education, abolishing rules that prevent the able from getting ahead and refocusing government spending on those that need it most. Oddly, the urgency of these kinds of reform is greatest in rich countries, where prospects for the less-skilled are stagnant or falling. Second, governments should get rid of rigged rules and subsidies that favour specific industries or insiders. Forcing banks to hold more capital and pay for their implicit government safety-net is the best way to slim Wall Street’s chubbier felines. In the emerging world there should be a far more vigorous assault on monopolies and a renewed commitment to reducing global trade barriers — for nothing boosts competition and loosens social barriers better than freer commerce.

Globalization and Inequality

An editorial in the Nation, a Bangkok newspaper, read: “The future of uncontrolled globalisation is massive income disparity, hyper-inflation, wage stagnation, poverty and revolt. The social and political upheavals in Tunisia, Egypt and other Arab countries are now rooted firmly in the growing income disparity. The cake has not been divided equally between the haves and the have-nots. Yet this is a global phenomenon that has been brought about by the economic and global integration of the past few decades. [Source: Nation, a Bangkok newspaper, February 18, 2011]

It might be true that globalisation has lifted millions out of poverty, yet it has also left billions of others behind in a worsening state of impoverishment. There are more than 6 billion people on this planet, but 2 billion of us are living on just US$1 to $2 dollars a day. When commodity prices rise sky-high as a result of monetary inflation, the poor can only revolt - because they are forced to spend 50 to 80 per cent of their wage on food and other basic necessities. It is safe to say that the uprising in the less-developed economies is the consequence of central banks' money printing, which erodes confidence in currencies and drives commodity prices to record highs.

Let us take a look at the income distribution in the United States, the model of free-market capitalism. The US situation is no better than other countries, with the rich racking up most of the benefits from the growth and capital gains of the last decade. An online article by CNNmoney.com called "How the middle class became the underclass" gives us a clear picture of an income distribution that has gone wrong over a generation. And it is getting worse. It has been found that 90 per cent of Americans have been stuck in a neutral or constant income level for decades, while the richest Americans have enjoyed the lion's share of economic wealth generation.

"In 1988, the income of an average American taxpayer was $33,400, adjusted for inflation. Fast forward 20 years, and not much had changed: The average income was still just $33,000 in 2008, CNNMoney quoted IRS data as saying. "Meanwhile, the richest 1 per cent of Americans - those making $380,000 or more - have seen their incomes grow 33 per cent over the last 20 years, leaving average Americans in the dust."

Experts have been trying to find the usual suspects for the huge income disparity. Some point to technology and globalisation; others to a decline in the trade unions and other labour protections, and to the hollowing out of jobs to the emerging-market economies such as China. But few address the core issue, which is the global imbalances, the indebtedness and corporate/banking structure that governs the markets, industries and economies.

Belgian Congo

We may have reached the dead-end of growth, as the current system has exhausted resources and the capacity for further consumption to drive growth. As the recession continues and inflationary fire has taken root, we will be seeing more failures in governments if not nation states due to the disintegration of the social and political fabric.

Dominique Moisi, a French intellectual, wrote, “It would be absurd to condemn, as some do, globalization as the main and only culprit in the erosion of traditional sources of support for the poor. Globalization is above all a context, an environment, even if the consequences of the first major financial and economic crisis of the global age will further deepen the gap between the very rich and the very poor. But globalization makes the weakest among us more visible, and therefore makes the absence of social justice more unacceptable. A world of much greater transparency and interdependency creates new responsibilities for the rich. Or, more precisely, it makes the old responsibility to protect the weakest both more difficult and more urgent.

Need for More Global Cooperation

Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “There's a danger we're already sowing the seeds of the next great financial crisis. We need better global coordination to address the biggest transformation of the world economy in history. In our interdependent world, only concerted action across continents can tackle these challenges. [Source: Gordon Brown, Christian Science Monitor, April 25, 2011]

Two years ago, the formal creation of the G20 helped prevent the world recession from becoming a world depression. World leaders agreed to a $1 trillion underpinning of the world economy, and strengthened the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Trade Organization. In its concluding statement, however, the G20 promised more: that it would work towards implementing new global standards and regulations across the world’s banking system, and that it would be the architect of a global growth agreement designed to deliver rising prosperity and create jobs in the decades ahead.

Two years on, what some now call mini-lateralism seems to be the order of the day. The immediate crisis has passed, and despite outstanding leadership in our international institutions and bold international initiatives by some national leaders, many governments have retreated into their national shells. We cannot agree on the proposed “global growth pact”; a world trade agreement is yet again stalled, risking the first failure of a planned trade agreement since 1948; and even after a nuclear catastrophe in Japan and a period of violent volatility in oil prices, there is still insufficient momentum for a global climate change agreement.

So what has happened? The need for cooperation cannot be in dispute. Indeed, this year the world is facing an unremitting onslaught of new challenges — food shortages, commodity price increases, youth unemployment and social unrest, and large imbalances even as inflation reappears. Some now talk not of a crisis but of crisis-ism, a state of ever-recurring crises that cannot easily be resolved by nations acting autonomously.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012