LABOR IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

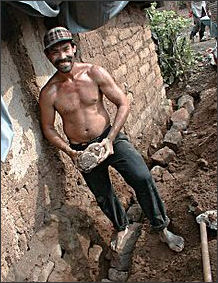

Villagers often work seven days a week, 52 weeks a year, doing this and that. In a typical week the father works 80 hours and the mother works 126 hours (18 hours of daily housework and a variety of chores). The poor generally do not take vacations, but have opportunities to rest during agricultural down times.

Many men live and work in the cities and send money home to their families in their village. People who work overseas or as shopkeepers and laborers in their cities are often treated like big shots back in their home village.

The biggest worry that many workers and farmers have is getting hurt or sick. In many cases the can't afford proper hospital care and their wages or earnings from crops are not enough to cover medical costs. Plus if they can’t work they can’t earn money to feed their families. Many who do get injured seek help from a local healer and to do not fully recover and are unable to get factory work again.

The issue of hiring and firing workers in companies that are often supported by the government are often dealt with differently than in the West. One labor expert told the New York Times that while decision on laying off people in the United States is often based on the “cold-hearted business perspective” in other countries decisions on such matters are often defined more by political considerations, legal restrictions and cultural taboos. Often it is easier to marginalize a worker than fire him.

It is not common for a person with a good job to take care of his or her family but also nephews and cousins. One NGO worker told National Geographic, "300 or more members, the extended family can be a massive burden. In small privately owned business...the owner has to fulfil his obligations to his family by providing jobs...One small body shop here does a good business and could provide a decent living for the owner, his son and two brothers. Instead it has 17 employees, all family whom the owner was obligated to hire, with the result that no one makes a descent living, the owner cannot expand, and his own family is living just above the poverty level."

Third World Sweatshops

Chinese-made bobbing head dolls Sweatshops are small factories that produce things like garments and shoes and light assembly plants that produce things like toys and cheap electronics. Stereotyped ones are hot, stuffy places, hence the name, where workers put in long hours, often working under harsh conditions, for low pay.

Most poor people would like to see more sweatshops rather than less of them. They provide scarce jobs for people who otherwise wouldn’t have jobs. Even salaries of two or three dollars a day, which seem minuscule by Western standards, are a lot of money for people living on sustenance level in agricultural villages.

Sachs and Paul Krugman of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, say that sweatshops are the first step taken by developing countries on the road to becoming developed ones. The economies of Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea all got started with sweatshops.

Responding to critics of sweatshops, Krugman told the New York Times, "A policy of good jobs in principle, but no jobs in practice, might assuage our consciences but it is no favor to its alleged beneficiaries.”

Nike, Reebok, Adidas and Poor Working Conditions

Nikes are manufactured in Vietnam, China, Indonesia and Thailand. It has been criticized for hiring underage workers, paying subsistence wages, hiring abusive managed and exposing employees to dangerously high levels of toxic chemicals.

Nike produces 78 million shoes a year from contract manufacturers in China. About 160,000 workers in China rely as 2001. Nike says the labor cost for a $85 shoe are about $2.50. If materials are included the cost is $16. If administrative labor is excluded the labor cost are only about $1.

Some Nike factories have been described as "little more than prison labor camps." Employees work 72 hour weeks and can be fired for refusing over time. One study found that workers at factories that make Nikes and Reeboks, monitored in 1995 and 1997, earned as little as 10 cents an hour and toiled for up to 17 hours a day. In response to criticisms, Nike asserts it doesn't make shoes, it subcontract the work.

Responding the criticism Nike promised to raise the age of employment to 18. improve safety use water-based rather solvent-based glues and use machines that do cause serious injuries. Some factories offer free day car and health checks and provide continuing education for their employees.

Adidas has been accused of using slave labor to make soccer balls. According to a lawsuit brought on behalf of dissident Baso Get, political prisoners in China "were coerced into waxing, stitching, and sewing Adidas soccer balls 14-18 hours a day in inhumane conditions" to make soccer balls for the 1998 World Cup. In 1998, Tim Larimer of Time wrote: "Nike's factories in the region are above average...[We] found them to be clean, brightly lit and well-ventilated. Where the employees have to use foul-smelling glues, there are plenty of fans to carry the fumes.”

See Separate Article WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Working Women

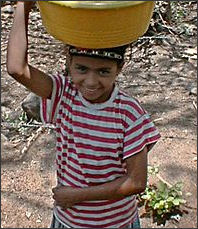

Mayan woman making souvenirs It is not unusual for girls to be pulled out of school when they are ten or so to work in the fields. When they are 14 or 15 they are sent off to work in factories far from their home towns

In China in imperial times women were prohibited from holding official position and prevented by foot binding from doing many kinds of physical labor. They worked hard at domestic chores and produced textiles for the home and to sell. The Communists claimed to give equal rights in regards to work and employment opportunities. Equality existed more in theory than in practice. Women toiled in factories and on farms and worked as teachers and doctors but held relatively few positions with power or real decision-making.

There are a fairly large number of female doctors in China. Even so women generally don’t hold very high-status positions or jobs. They are often encouraged to become secretaries, tour guides and hostess, not lawyers, managers and executives. Women are usually the last hired and the first laid off because unemployed women are considered less "socially destabilizing" than unemployed men.

Women in China traditionally control family finances. Millions of housewife have invested their family's money in real estate and stocks and four million operate private firms of a "substantial scale." A survey in 2000 by J. Walter Thompson on goals found 74 percent of the women interviewed ranked personal success first, 54 percent chose wealth and only 19 percent picked friendship.

Slaves, Bonded Servitude and Forced Labor in the Developing World

An estimated 2.5 million people are trafficked and enslaved each year. By some counts there are 30 million slaves in the world today.

Some villagers are little more than indentured servants to landlords who give the peasants loans which they can not pay back. The landlords then set the prices of the crops and the terms of the payments and make nice profits while burdening the villagers with such heavy debts that even their children and grandchildren will never be able to pay them back.

About two thirds of the world’s bonded captive laborers are in found in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. According to Human Right Watch there are 65 million adults and children working as bonded laborers, many working to pay off debts of their fathers, and even grandfathers. Virtual slaves, they are often indebted to the same people who pay their wages. Often their wages are so low they have no hope of every escaping from their debt.

Bonded servants in India work as laborers in stone quarries and farms and are used to weave carpets. Many people have become bonded serfs by falling into debt to come up with payments for dowries. Many children don't go to school because they have been sold into bonded serfdom by their parents.

Brick kilns have entire families of bonded servants working for them. Men are often put to work stoking the kilns while women and children carry the bricks and firewood. The kilns often obtain workers by lending money to poor families for expenses far beyond what they can afford, such as for health care, a wedding, a dowery or a funeral and then force them unto indentured servitude to pay back the loans. The period of servitude is prolonged by increasing their debts with loan-shark interest rates and shady bookkeeping.

Legislation and efforts to stop bonded servitude have largely not worked. Some have been released from bondage by police.

Anti slavery groups: American Anti-Slavery Group (www.iabolish.com ); Anti-Slavery International (www.antislavery.org ); Coalition to Abolish Slavery (www.castla.org ) Free the Slaves.

Child Labor in the Developing World

An estimated 200 million children worldwide, aged 5 to 14, work. The streets in tourist areas are often filled shoeshine boys who let their presence be known by tapping their brushes on the edges of their wooden boxes and children who roam from café to café selling cigarettes, chewing gum, lighters, batteries, tissue packets at other small items.

Many more work as laborers and sweat shop workers. Describing a6-year-old boy and girl child laborers who carried bricks on their back from an oven to a brickyard, New York Times photographer Jean-Pierre Laffont said, "They don't grow up, their legs arch and they stay five feet tall." The children played and rested while the bricks baked and then went to work when the oven door opened. "These kids feel that they accomplish more by working than the kids who go to school, producing nothing. They think they are imitating adults before they understand they are working."

Most children who work in the developing world — from 92 percent in Vietnam to 63 percent in Guatemala — are engaged in agriculture. They do things like fetch water and tend livestock, work for their families and are not paid directly. Many children, especially girls, are employed as domestic servants, They are denied access to education and vulnerable to sexual abuse. Over all relatively few work in factories.

The conventional view on child labor was that it was a manifestation of parental ignorance about the benefits of education. Policies focused on educating parents on the benefits of education and banning children’s employment to remove the temptation.

Studies seem to show that child labor is a manifestation of poverty and that in many cases parents would prefer to send their children to school but have no choice but put them to work to help the family scrape by. Studies show that as income levels rise children are more likely to go to school; when income levels drop they are more likely to work. Eric Edmond, an expert of child labor at Dartmouth College told the New York Times: “In every context that I’ve looked at things, child labor seems to be almost entirely about poverty. I wouldn’t say it’s only about poverty, but its got a lot to do with poverty.”

Industry in the Developing World

Textiles is an important industry in many developing countries and are relatively easy to start up. Textile factories employ lots of people.

Most textile products are made by small factories or cottage industries with a work force that is 75 percent or more female. Most of these women are between the ages of 16 and 24, who earn as little as $1.80 a day and work six days a week. Most major clothing and shoe companies have their products made in the developing world.

See Separate Article CHEAP LABOR INDUSTRIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

”Better Work” and Difficulties in Monitoring Factory Work Conditions

In March 2012, Rachel Louise Snyder wrote in the Washington Post: Monitoring, when done effectively, takes a lot of time, from two days to a week. It’s not simply a matter of walking around a factory checking ventilation systems, light bulbs and fire exits; it’s painstakingly comparing export records with buyers’ contracts and calendars (to make sure that work is not happening on a Sunday, say) and sometimes even weather reports. If multiple groups are auditing a factory annually, it can spend weeks out of each season just working with them. One factory I visited in China had an entire department devoted solely to working with the many monitors who came through. On top of that, third-party monitoring is very expensive. The International Labor Organization puts the cost at $1,500 to $3,000 per audit, and many factories are audited five or six times in one month, though the frequency varies greatly. [Source: Rachel Louise Snyder, Washington Post, March 30, 2012]

Underage employees are often weeded out by auditors simply walking around attempting to spot young-looking workers — most often girls — or thumbing through employee records. I interviewed dozens of workers in the course of writing a book about the global manufacturing industry, and every one told me that she would help hide underage co-workers if need be, because the families of these girls must be in dire straits to send their daughters to work.

There is, though, a better way. Cambodia has proved it. In the late 1990s, the country negotiated a deal with the Clinton administration that linked good factory conditions to increased access to the U.S. market. Cambodia brought in the International Labor Organization to oversee factory monitoring and create unions, among other things, and in less than a decade, garments became the country’s primary export — more than 95 percent of all goods exported, in fact. Eventually, the ILO turned over administration of the program to local authorities. And while there were factories that fell out of compliance, and mistakes were made, by and large it was a successful experiment.

Kohler factory

Today, federal law guarantees the garment workers of Cambodia breast-feeding breaks, 43 paid vacation days annually, medical clinics on site and 90-day paid maternity leave, among other things. The program, called Better Factories Cambodia, has become a model for many other countries. That program, now called Better Work, is used in Haiti, Lesotho, Jordan, Nicaragua, Indonesia and Vietnam. It is a partnership among the ILO, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, international brands, local factories, local governments and nongovernmental organizations. It costs $7 million to $10 million over the course of five years to establish the program — though in a country the size of China, it would be much more. Half the money so far has come from development grants, and the other half from fees shared by factories, international buyers, unions and local governments. While it might sound like a lot of money, it is far more economical than the ad hoc system of third-party monitoring. The ILO estimates that Better Work will ultimately cost just $2,000 per factory annually.

The program also streamlines many of the economic, cultural and political issues surrounding international brands and third-party auditors working in foreign arenas. “Factories don’t live in isolation,” one ILO official told me several years ago. “They live in the context of laws and the country. Say your factory is great, but outside the factory there’s no rule of law. It creates fear in the community. All of us are realizing we have to have a way to move forward at the enterprise level, but it’s got to be broader than that. You’ve got to build the nations’ ability to run good labor standards and industrial relations.”

Apple, admittedly, is in a tight spot. China does not allow formal labor unions (apart from the government’s own union), and labor laws are generally set by prefecture rather than at the federal level. Allowable overtime, for example, might differ from one area to another. To get around this, one factory I visited in China had created its own worker-led union to advocate for workers with management. The reality is that Apple has the influence, economically and otherwise, to flex a little muscle. The company has long been visionary when it comes to technology that enhances the lives of privileged Westerners. Now let’s see if it can take on the moral and ethical challenge of improving the lives of its overseas workers.

”Ethical Supply Chain” Movement

According to The Economist: Any big company that makes things in poor countries faces scrutiny of its supply chain. Campaigners against harsh working conditions (and unions back home that hate competition from low-wage countries) will pounce on any hint of scandal. Horrified headlines can tarnish a brand. Companies need to pay heed. Wages for factory workers in China have been soaring at double-digit rates for years, for reasons that have little if anything to do with Western activists and a lot to do with productivity improvements. But some workers are abused, as even Apple admits. [Source: The Economist, March 31, 2012 ]

Bamboo furniture makerAfter a bad press in the early 1990s, Nike is now one of the loudest advocates of improving working conditions. In 1992 it established a code of conduct for suppliers. In 1996 Nike helped create the Apparel Industry Partnership, which drew up a code of conduct for factories, and in 1999 evolved into the FLA. Having a code of conduct and being part of an industry initiative on workers’ rights has become standard practice for multinationals. But there are big differences in the toughness of codes, how rigorously compliance is monitored and how remedial action is taken.

Factory audits also vary. Nike first published the overall results of its monitoring in 2000, but did not list details of all the factories in its supply chain until 2006. (Apple did not publish details of its supply chain until this year.) When Nike opened up it was a conscious effort to challenge industry norms. Clothing and shoe firms took it for granted that revealing which factories they used would put them at a competitive disadvantage. But Nike reckoned the downside was negligible and the lack of transparency hindered the monitoring process, says Hannah Jones, the firm’s head of corporate social responsibility. Secrecy led to some factories that worked for a variety of companies undergoing multiple audits. Other factories escaped entirely.

Another challenge is preventing corruption, says Alan Hassenfeld, a former boss of Hasbro who is now the driving force behind the International Council of Toy Industries’ code, called ICTI Care. Factory managers sometimes bribe auditors. Some firms use fake books showing shorter hours and higher pay. Some workers collaborate in these violations more willingly than is assumed. Many migrants, for example, want to work long hours to save as much money as possible in a short time — and then go home.

Limitations of the “Ethical Supply Chain” Movement

NGOs can be both a help and a hindrance, reckons Mr Hassenfeld. Some only campaign. Others work with firms to help put things right. Some do both. Campaigning NGOs can put pressure on a firm to do better, but they rarely support it when expelling a factory from its supply chain, which also hurts workers, says Mr Hassenfeld. “One of the things we need to do is be tougher with repeat offenders, to make an example of them,” he adds.

”Governments are not pulling their weight,” complains Aron Cramer of BSR, an NGO. He thinks there has been “too much outsourcing of enforcement to the private sector”. Individual firms may find enforcement difficult. Governments may do better, but few governments of emerging markets like to be bossed around.

”Nobody thinks this process is perfect, but we have made progress,” says Mr Hassenfeld. Mr Cramer agrees. At least for firms at the top of the supply chain, “the old problems of forced labour and child labour are largely gone,” he says. The worst abuses tend to be further down the supply chain, and in particular sectors, such as agriculture and mining. Nonetheless, there remains much to do even among first-tier suppliers on things like excessive hours and inadequate pay, says Mr Cramer.

Making Real Improvements to the “Ethical Supply Chain”

The Economist reported: Richard Locke of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has taken a detailed look at how things really work. He persuaded four global firms regarded as leaders in ethical supply chains (Nike, Coca-Cola, HP and PVH, a big American producer of clothing) to let him analyse six years of data from their factory audits, starting in 2005. His research, to be published this year in a book, “Promoting Labour Rights in a Global Economy”, drew four conclusions. [Source: The Economist, March 31, 2012 ]

First, codes of conduct, compliance programmes and audits “[do] not deliver sustained improvements in labour conditions over time,” he says. Rather, these things help gather information that highlights the problem without remedying it. At HP, for example, only seven of the 276 factories in its supply chain fully complied with its code of conduct at the last audit. At the factories he visited, Mr Locke typically found that many suppliers serving global brands drift in and out of compliance.

Second, investing time and money in helping factories improve their managerial and technical capabilities did produce some benefit in improved working conditions. But his third conclusion found that for significant and sustained improvement to take place, the relationship between a company and its suppliers needed to change too. The relationship had to become more collaborative. In particular, gains from changes in the production process needed to be shared.

Mr Locke’s fourth conclusion poses the toughest challenge. For firms trying to improve working conditions the fault may well be in their own business model. Just-in-time manufacturing has made supply chains leaner. Slimmer inventory cuts costs and allows firms to move more quickly. As products’ life-cycles shorten, this is a crucial competitive edge. But a last-minute design change or the launch of a new product can mean suppliers having to pull out all the stops to keep up — or face a stiff financial penalty.

Timberland, a bootmaker and vocal supporter of ethical working practices, admitted as much in 2007 in a company report, noting that “some of our procedures were making it difficult for factories to control working hours”, including developing a huge number of new styles and the simultaneous launch of many new products. Nike has since said much the same.

As part of his research, Mr Locke visited an inkjet-printer factory in Malaysia which, at its historic peak in 2007, produced 1 million products a month for HP. The factory, which made six to eight models a year with an average lifespan of less than nine months, experienced extreme demand volatility — with the result that it sometimes had to increase monthly output by 250 percent, then cut it again. This forces suppliers to ask their workers to put in vast amounts of overtime. Apple’s product launches presumably produce similar surges.

Nike’s Ms Jones says her company has taken this to heart by trying to incorporate the need to protect workers into the design of its production process. She is now jointly accountable for enforcing the code of conduct with the head of the supply chain, a change which she says has removed an “us-versus-them problem”. Members of Nike’s 140-strong corporate social responsibility team are now involved in all branches of the supply chain. The firm is thinking harder about how it schedules product launches. And it espouses a philosophy of continuous improvement by delegating more responsibility to workers. This will only work if they are treated well, says Ms Jones.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; China Labor Watch; Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012