FOOD AND FOOD CROPS

Ivory Coast market

Fermentation is as important for foods as it is drinks. Bill Buford wrote in The New Yorker, “Fermentation has been around forever. It is older than cooking. It was probably the first method of food preparation. Fermentation transforms grapes into wine, grains into beer, wheat into leavened bread. It transforms a raw ingredient, often valued for its nutrition, into one valued for its taste. It yields vinegar, yogurt, sauerkraut, cheese, prosciuto, vanilla and pickles. It occurs most readily in fruits, because they have, in abundance, the two essential elements: sugar and yeast. A yeast is on a leaf or a branch or in the air. It is a fine white powder on the skin of a grape, like a dust that you should wash off. At its most basic, fermentation is how sugar becomes alcohol. See Alcohol

Traditionally mankind has relied on 7,000 plant species for their basic food needs. These days, mechanized agriculture has whittled that number down to 150 species, with the majority of people living on only 12 different plants. Hundreds of varieties of corn, wheat, potatoes and tomatoes and other crops have disappeared. Many blame the Green Revolution which promoted the standardization of agricultural techniques and the use of uniform, high-yield crops.

Many of the world’s food crops come from single strains or varieties that are vulnerable to devastating diseases or pests like fungus that caused the Irish potato famine in the 19th century, Panama disease which wiped out much of the commercial banana crops in the 1950s and 60s or a corn fungus that devastated the corn crop in the southern United States in 1970. Different varieties may also be needed in the future to meet challenges presented by changing climate conditions associated with global warming and other environmental challenges.

There is a growing movement to protect crops diversity and discourage use of single crop types. The United Nations Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, which goes into effect in 2006 requires countries to preserve existing crops and calls for the creation of an international system for sharing crops and plant genes. Unfortunately, already many strains and plant types have been lost

Widely consumed and used food crops are sold in world commodities markets. Sometimes people buy futures (a promise to buy a commodity in the future at a specific price) as a hedge for some unforseen problem or as speculative move to make money. The world price for commodities is often set as much by speculation as it is by economic fundamentals such as production, demand and supply.

There are commodity markets for food crops. A futures contact is an obligation to buy or sell a commodity at a set price for delivery by a specific date.

Grapes, wheat, barley, rice, various legumes, melons, dates, pistachios and almonds are the earliest known crops. See Separate Articles Agriculture, Crops, Grains and Fruits factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) statistics faostat.fao.org ; Index Mundi food statistics indexmundi.com/en/commodities/agricultural ; U.S. Department of Agriculture Info ers.usda.gov ; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) agricultrual production fao.org/economic/ess ; Food Timeline, History of Food foodtimeline.org ; Food and History teacheroz.com/food ; Food Issues, Food Museum foodmuseum.com ; Center for Global Food Issues cgfi.org ; Global Issues globalissues.org/issue/749/food-and-agriculture-issues ; International Institute of Tropical Agriculture iita.org ; Food reference.com foodreference.com ; Purdue University Crop Index hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/Indices ; World’s Healthiest Foods /whfoods.org ; Cambridge World History of Food (a few chapters available online) cambridge.org/us/books ;

Book: “Oxford Companion to Food” by Alan Davidson (Oxford University Press, 1999); “The New Oxford Book of Food Plants” by J.G. Vaughun and C.A. Geissler (Oxford University Press)

Flavor and Scent Industry

The food and flavor industry is led by two companies: Givaudan, the industry leader, and International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF), the close-behind No. 2. Givaudan has been compared to Coke and IFF to Pepsi, Together they control about 30 percent of the of the $18 billion global market for flavors and fragrances that not only embraces food and perfumes but also toothpaste, shampoos, deodorants and cleaning products. IFF’s five largest customers are Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Colgate, Estee Lauder and Pepsi. [Source: Jeremy Caplan, Time magazine, May 14, 2007]

Beans in a market in India

IFF spends about 9 percent of its revenues, or $185 million, on research. It employs more than 100 scientists whose job is not just to produce smells and flavors but to devise clever strategies on how to embed scents and flavor into products. Among the most valuable employees are noses who are experts at determining flavors and scents. IFF values its noses so much two of them are not allowed to fly on the same plane. When bonuses for successful flavors and fragrances are factored in IFF’s best noses can earn over $1 million a year. Some are so skilled they can pick up almost any product and identify the three most prominent notes by smell and can often tell you who designed it.

Also valuable are “scientists” who travel the world on “scent treks” to locate new flavors and scents. They may travel the globe checking out a plant in New Guinea that produces a chocolately flavor, a particularly tasty spicy soup in Sichuan, China or some clay or cardamom flowers from southern India. Many of them carry a solid-phase micro extractor, a $100 penlike device that can record specific molecules present around objects. In their laboratories they rely on bell-shaped cells that captures the “headspace” or air around living plants. This can be analyzed using chromatography and mass spectrometry and computer programs that map out the components. Most plants have 60 to 100 primary components and as many as 100 minor tones. Sometimes the smell can be duplicated using a company’s supply of natural and synthetic oils. [Ibid]

Vegetarians and Organic Food

Some trace the origins of vegetarianism to the Pythagoreans of a Samos, a community of 5th century B.C. mystical mathematicians that generally avoided eating meat on the grounds that animals have “a right to live in common with mankind.” The idea was brought back in the 4th century A.D. by Neoplatonists who saw it as means of purifying the soul in the quest for the afterlife.

Vegetarianism has been part of Hinduism for longer and part of Buddhism for almost as long. Most devout Buddhists are vegetarians who are opposed to killing any animals. Buddhists believe in reincarnation and they maintain that killing an animal is killing the soul of a being that may one day be a human being. Many Buddhists go as far as rescuing insects from their tea. Some Buddhists hold special ceremonies for dead chickens or dead fish.

Hindus believe that all living creatures — from bacteria to blue whales, and even some plants — have souls, which are essentially equal, and all these life forms are manifestations of the unity of the universe. This is why Hindus are vegetarians and abhor killing animals; and “ahimsa” , the belief that it is a sin to harm any living creature, is an important precept in Hinduism. The concept was eluded to in the Upanishads and contrasts sharply with doctrines of Western religions which holds that mankind is a special creation on a plane higher than other creatures.

Lee Silver, a professor of molecular biology at Princeton and a major proponent of GM food, wrote in Newsweek: “Consumers tend to assume that all organic crops are grown as advertised without chemical pesticides. This is false. Organic farmers can spray their crops with many chemicals including pyrethrin, a highly toxic pesticide, and rotenone, a potent neurotoxin recently linked to Parkinson’s disease. Because these substance occur in nature — pyrethrin is produced by chrysanthemums and rotenone comes from a native Indian vine — they are deemed acceptable for use on organic farms.”

Book: “Bloodless Revolution: A Cultural History of Vegetarianism from 1600 to Modern Times by Tristram Stuart (Norton, 2007).

Food, Population, Famine and History

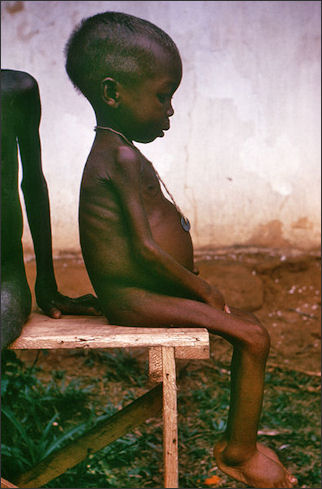

Starved girl in Biafra in the 1970s Ever since agriculture was developed around 12,000 years ago agricultural advancements such as the domestication of animals, irrigation and rice production have lead to corresponding increases of population. By the same token when agricultural productivity plateaued so too did population. Arab and Chinese writers made note of the relationship.

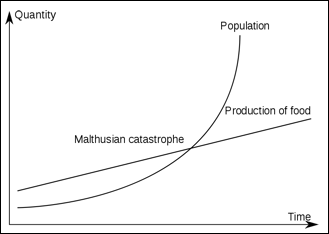

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) is the father of the idea that human population is doomed by overpopulation and the limitations of what the Earth can provide in terms of food. Malthus wrote that if unchecked population increases geometrically — doubling every 25 years or so — while agriculture advances more slowly at an arithmetic pace. “The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man,” he wrote in “Essay in the Principle of Population” in 1798. “This implies a strong and constantly operating check on population from the difficulty of subsidence.” Among the checks he mentioned were birth control, abstinence , delayed marriage, war, famine and disease.

Traditionally as long leaders were able to keep their populations fed they remained in power but had problems if they couldn’t. The Ming dynasty was ousted in China after a famine. Revolutionaries that ousted Marie Antoinette and the French king were motivated by hunger as much as anything else. One of the primary reasons the British decided to leave India was they realized the could not cope with the consequences of famine there.

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, author of “Food: A History”, wrote in the Times of London, “The Natufians of Syria — the first sedentary civilization in the world, whose people once enjoyed such abundance that they could build permanent settlements while living on wild grains and products of the hunt — ran out of food 14,000 years ago. The graves of Minoan Crete, where oil and grain once filled the great palace labyrinths are full of malnourished bones. Environmental overkill helped to exhaust the soil and empty the cities of the Maya lowlands...A couple of centuries later, food failure wiped out the civilizations in the south-west of North America...The Aztec Empire collapsed when invaders cut off its supplies. Famines checked growth repeatedly in Europe until new crop varieties solved perennial food shortages in the 18th century.”

Books: “End of Food” by Paul Roberts (Houghton Mifflin “Food: A History” by Felipe Fernandez-Armesto;

Hunger

Despite all the advances that have been made with the Green Revolution and improvements with agriculture, hunger remains as much of a problems as it ever was. More people are hungry today than ever. In 2008 and 2009, the economic crisis and high food prices pushed the number of hungry people over 1 billion according to United Nations food officials. In some cases families cut back on school clothes and basic medical care so their children could have a meal according to a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report.

Why do hunger and food shortages exist in some places while people grow fat from too much food in other places? The answer is complex and involves many things: food prices, weather, depletion of soils, corruption in African countries, American farm politics, war, poverty, global warming, among other things. Many blame neglect and a lack of political will for not effectively tackling the problem.

Malthus's Theory

Norman Borlaug, the father of the Green Revolution, said in 2007 that “the battle to ensure food security for hundreds of millions of miserably poor people is far from won...World peace will not be built of empty stomachs. It is within America’s technical and financial power to help end this human tragedy and injustice, if we set our hearts and minds to it.”

The success of the Green Revolution has also been blamed. Andrew Martin wrote in the New York Times, “So much grain was being produced so cheaply that Western leaders encouraged poor nations to buy grain on the world market rather than grow it themselves. Surplus was shipped to poor countries as food aid. But that aid system has often been ineffective in alleviating hunger in a timely way and in dressing broader agricultural problems facing impoverished countries, Support for agricultural research in developing countries was also cut back for other priorities, The result? While the food supply grew faster than the world’s population from 1970 to 1990, as the Green Revolution’s gains took hold, the situation has now reversed itself. Productivity gains in agriculture have slowed, and since 1990, the growth rate of food production has fallen below population growth.”

A food summit at the United Nations’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome was held in November 2009. It was quickly labeled a failure even before it really got going as the delegates for 192 countries failed to commit themselves to $44 billion in annual agricultural development aid. To show sympathy for and solidarity with the world’s 1 billion poorest people on the eve of the meeting, the head of the Food and Agriculture Organization, Jacques Diouf, called for global day of fasting.

Small Land Owners in the Developing World

A typical subsistence farm contains a vegetable plot, a mango or banana grove, and larger plots with maize, cassava, rice or sorghum. A farmer may own a few chickens or some pigs. If he is lucky or relatively well off he may have a water buffalo or a cow.

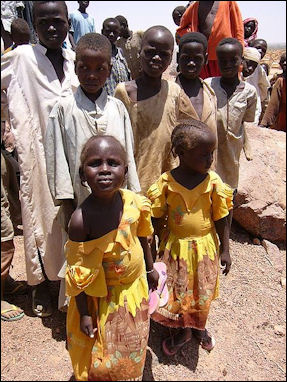

Refugee children in ChadPoor farmers eat most of what they grow. With the help of fertilizer and erosion control, they can raise enough to feed their families and have a little left to sell but remain poor. Sharecroppers working for landowners generally have to fork over a large share of grain or a cash crop to pay their landlords for rents. Local official may demand high taxes.

Villagers need money for improved seeds, tools, machinery, fertilizer and pesticides. They can't afford tractors or often even plow animals and fertilizer is so precious it is carefully dispensed a handful at a time. Villagers have to be careful about borrowing money to buy animals or fertilizer. Money is often borrowed at high interest and one bad harvest can mean the loss of their land.

Some farmers have traditionally divided their land equally among their oldest sons. But often the land has been subdivided so many times that individual plots do not produce enough food to feed a family. Others have been kicked off their land so that cash crops can be grown for export to earn money to pay off government debts.

Large Land Owners in the Developing World

In some countries cash crops have traditionally been raised on plantations with production concentrated into the hands of so few landowners that one percent of plantations raise 45 percent of the country's sugar and coffee. Money from these crops provides the financial base of the oligarchy, the country’s wealthiest families.

Although most of the money from African exports during the colonial period came from mining, agricultural exports also increased. The land was cultivated one of three ways: 1) by peasant farmers on small plots of land; 2) black laborers on farms owned by white settlers; or 3) on large plantations run by big companies. Peanuts, cocoa and palm oil were the major export products.

White plantations often failed because the farmers were ignorant of tropical agriculture and their specialized farms were vulnerable to pests and disease. There was a shortage of labor so new plantations had a hard time attracting labor cheap enough to make their enterprises profitable.

"The development of the [cocoa] industry," wrote Nigerian governor Hugh Clifford, "has been practically spontaneous on the part of the inhabitants. The inevitable result of the rapid increase of the people's wealth has been to bring about what almost amounts to a revolution. The commensal ownership of the land is being largely repudiated for individual ownership.; the sale of the land , and almost unheard of practice has became a matter of everyday life; a tendency for the maker of a cocoa plantation to leave his property to his son rather than his sister's son has brought about a change from matrilineal to patrilineal descent.”

Fertilizer Prices and Phosphorus Shortages

Another problem that has to be dealt with is high fertilizer prices. When oil prices rise so too do the prices of petroleum-based fertilizer. There is also a looming shortage of phosphorus, a key ingredient of fertilizer. Increased agriculture production increases use of phosphorus. The drive to develop biofuel and increased meat consumption are viewed as a threat to phosphorus sources. During the food crisis in 2008 the price of phosphorus surged more than 700 percent to $367 a ton in 14 months.

There are no synthetic alternatives to phosphorus. Scientists at the University of Technology in Sydney estimate that current supplies will be depleted in 50 to 100 years. In Sweden scientists are designing toilets that separate and collect urine and then derive phosphorus from it.

The are lots of phosphorous sources but few of them are suitable for mining. Morocco holds 32 percent of the world’s proven reserves of phosphorus. Other large reserves are found in Western Sahara, South Africa, Jordan, Syria and Russia.

Higher Food Prices

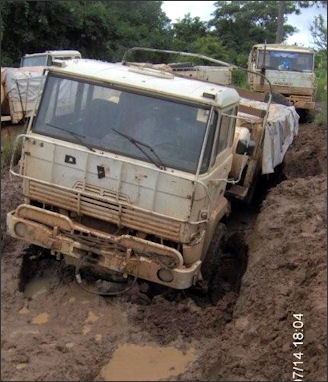

road in in Central African Republic

Some see higher food prices as a long-term good thing in that they would make food more precious and valuable and the resources needed to produce them would be better appreciated. Plus, more money could flow to farmers and this would hopefully improve the lives of farmers in developing countries by giving them more money for their crops.

Improving the agricultural sector is perhaps the best way to generate economic growth in poor countries. According to the World Bank, the very poor get three times as much extra income from an increase in farm productivity as from the same gain in industry or services.

The Economist reported: “Dearer food has the capacity to do enormous good and enormous harm. It will hurt urban consumers, especially in poor countries, by increasing the price of what already is the most expensive item in their household budgets. It will benefit farmers and agricultural communities by increasing the rewards of their labor, in many poor rural places it will boost the most important source of jobs and economic growth....If politicians do nothing, or wrong things, the world faces more misery, especially among the urban poor. If they get policy right, they can help increase the wealth of the poorest nations, aid the rural poor, rescue farming from subsidies and neglect — and minimize the harm to the slum dwellers and landless laborers.”

Roads, Food Distribution, Logistics and Crop Prices

The fortunes of farmers who grow cash crops like coffee, sugar and cacao rise and fall with the fluctuated world prices of these commodities. Before they make decisions about what they are going to grow farmers must calculate if the world price or government subsidized price for their crop is enough to justify the expenses for new seeds, fertilizer and pesticide.

Explaining how her village markets its harvest one Chinese villager told Nature Conservancy magazine: “Our Jiyu Village is an administrative village that has the most croplands in the Lashi Township. So we grow and harvest more grain and cash crops here. Naturally more cropland means more hard work in the fields. During harvest time, crop dealers come to buy farm crops like flour, corn and beans, because the people in Tai’an only grow potatoes, we sometimes go there to sell our grain crops or exchange with people there for their potatoes.”

Hunger today is often more the result of inadequate distribution and lack of infrastructure than lack of food or crops. Many villagers have difficulty getting their crops to market before they rot because of poor roads. Some remote areas have been greatly helped by the completion of roads that link fields and farms to major roads.

Commodity Prices and the Negative Affects of Globalization

More than 2 billion people worldwide make a living producing agricultural commodities. The dependence on income from these commodities is especially pronounced in the 50 least developed countries, or LDCs. More than 85 developing countries depend on commodities for more than half their export earnings. High commodity prices can help farmers in these countries climb out of poverty. Low commodity prices can make the poor farmers even poorer and saddle them with crushing debts. The market is notoriously cyclical. For every high there is a crash.

While demand for commodities such as coffee, tea, cocoa, cotton and sugar has risen in recent years and prices for these goods has risen and consumers pay more for them at supermarkets and malls the money that farmers receive is often relatively less than what they received before. Robusta coffee producers in Ivory Coast, for example, received 17.5 percent of each consumer dollar spent on their product in 1980-88 but only 7.2 percent in 1999-2003. For coffer growers in Cambodia and Indonesia the decline was from 19.2 percent to 7 percent. [Source: Kemal Dervis]

As demand for commodities has increased production has increased to meet the demand. The production of rice increased by 67.5 percent between 1993-95 and 2003-05. In the same period cotton production increased by 48.8 percent, fresh and chilled vegetables was up 69.7 percent and flowers were up 72.9 percent.

Kemal Dervis, an administrator with the United National Development Program wrote: “The complexities of the “value chain” between production and the supermarket shelf do not work to the advantage of low-income, smallholder farmers. The process may be global, but the benefits do not reach the poorest. The higher end, where and natural textiles are “differentiated” — processed in ways that appeal, packaged attractively, branded and advertised — is where most of the money concentrated.”

“Part of the problem is that developing world governments are still learning how best to benefit from the globalization. During the 1990s, when the international financial mantra was that governments should keep their hands off and let the free market work, many developing country governments were told to stop negotiating prices and organizing transport and marketing for thousands of small farmers...A number of them, especially in Africa and Latin America, did stop, but private substitutes for these services did not appear and thousands of small producers with very limited access to market information, transport and credit were left to fend for themselves against very large, very sophisticated international buyers such as supermarket chains. And these farmers continue to compete will colleagues in developed countries who receive generous subsidies while home markets are protected by high tariffs.”

“Investment...has been lacking in roads and ports. If delivery is uncertain and slow, major international customers are less interested and pay less...Both public and private investment is vital: warehouses for groups of rural farmers, for example, makes a huge difference. If prices are low, they store their coffee or cocoa, and sell it when prices are up. Too often now they can only sell it when they have to. And higher end stuff-grinding, grading, standardizing, packaging — might happen in-country instead of far away, if the facilities could be built and expertise acquired.” In May 2007 a conference on these issues entitled “Global Initiative on Commodities: Building on Shared Interests” was held.

Empowering Women Farmers

In the developing world, much of the agricultural work is done by women. Female farmers grow around 80 percent of the crops grown for food consumption in Africa. In Africa and Asia, women have traditionally focused on the food production side of agriculture while men have traditionally grown cash crops or migrated to the cities for work. Despite this women own only a tiny percentage of the world’s land — estimates are generally less than 2 percent.

Former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan has called for women to be the heart of a “policy revolution” to improve small-scale farming in Africa. Annan said, “Today the African farmer is the only farmer who takes all the risk herself. No capital, no insurance, no price supports, and little help — if any — from governments. These women are tough and daring...but they need help.”

village woman in Bangladesh A 2008 FAO report highlighted the benefits of improving women’s access to technology, land and finance. The report said that providing equal land rights for women in Ghana could double the use of fertilizer and profits. It also said that elsewhere in Africa if entrepreneurial women were given the same education and inputs as men agriculture revenues would increase by 20 percent. A study in Ivory Coast found that increasing a woman’s income by $10 brings improvements to children’s health and nutrition that would require a $110 increase in men’s income.

Many countries have equal rights laws on their books but these are often poorly enforced and often they clash with customs that give property and ownership rights to men. In many cases if a woman’s husband dies she has to marry her husband’s brother to keep farming the family plot of land. Marcela Villareal of FAO’s gender equality division told Reuters, “People continue to think that doing things for women is part of a welfare program, and doing things for men — big investments or credit — that is agriculture, that is GDP-related. Women continue not to be seen as part of the productive potential of a country.”

In Malawi, the FAO is working with government leaders and village chiefs to inform women of their legal rights and provide them with wind up radios so they can listen to radio shows in their own language that gives them tips on farming and things liking writing wills. Among those involved in improving the conditions of women farmers is Rwanda’s agriculture minister Agnes Kalibata, , who has helped set up micro-financing for female farmers and given them access to markets and co-operatives, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has attached conditions on improving women’s farming to their grants.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012