PROBLEMS WITH FOREIGN AID

Aid in the Congo wasted The quality of foreign aid is often low and often inconsistent with trade policies and sometimes the donor countries benefit more from developing world programs than the countries they are intended to help.

A study by Oxfam and Action Aid reported that: 1) because of red tape, inefficiency and nepotism and other reasons only about one fifth of foreign aid actually reaches the people it is designed to help; 2) money is often channeled into “consultancy and infrastructure industries and geopolitical allies” rather than aimed at poverty reduction. In its worst form the report said it is “round tripping” — taking with one hand what is given by the other while advertising your generosity.”

The Oxfam and Action Aid report said inflated procurement and inefficiency cost $7 billion a year and “donors tend to more concerned about the success and visibility of their project or program that the success of a country’s development plan.” Then there is the problem of not paying up on pledges. In September 2010, the FAO noted that only a small fraction — $420 million — of the $20 billion in agricultural development assistance pledged by the 2009 Group of Eight developed nations summit and $2 billion more from a later G-20 meeting has materialized.

There is often little follow up or evaluation of programs to see if they worked, achieved the goals they set out to accomplish or improve the lives of the people who were targeted for help. When programs are evaluated they tend to be rated on how many schools are built, how many vaccinations are given, how many miles of road are built or how many micro-loans are given. Many think the best way to evaluate a program is through randomized evaluations in which the beneficiaries of a program are compared with non-beneficiaries to determine which group fared better. Drug companies use the method to determines whether drugs are effective.

Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, Aid organizations and their workers are entirely self-policing, which means that when it comes to the political consequences of their actions they are simply not policed. When a mission ends in catastrophe, they write their own evaluations. And if there are investigations of the crimes that follow on their aid, the humanitarians get airbrushed out of the story.” The journalist Linda Polman “suggests that it should not be so is particularly timely just now, as a new U.N. report on atrocities in the Congo between 1993 and 2003 has revived the question of responsibility for the bloody aftermath of the camps. There can be no proper accounting of such a history as long as humanitarians continue to enjoy total impunity. [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Legacy of Biafra and the Failure of Modern Humanitarian Aid

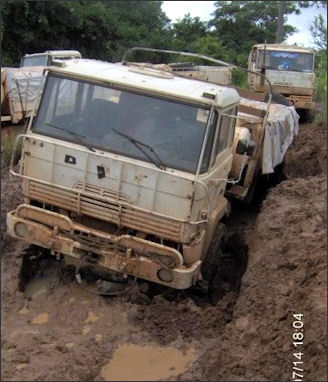

Food Convoy in Central African Republic Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “Since Biafra, humanitarianism has become the idea, and the practice, that dominates Western response to other people’s wars and natural disasters; of late, it has even become a dominant justification for Western war-making. Biafra was where many of the leaders of what de Waal calls the “humanitarian international” got their start, and the Biafra airlift provided the industry with its founding legend, “an unsurpassed effort in terms of logistical achievement and sheer physical courage,” de Waal writes. It is remembered as it was lived, as a cause célèbre — John Lennon and Jean-Paul Sartre both raised their fists for the Biafrans — and the food the West sent certainly did save lives. Yet a moral assessment of the Biafra operation is far from clear-cut. [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

After the secessionist government was finally forced to surrender and rejoin Nigeria, in 1970, the predicted genocidal massacres never materialized. Had it not been for the West’s charity, the Nigerian civil war surely would have ended much sooner. Against the lives that the airlifted aid saved must be weighed all those lives — tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands — that were lost to the extra year and a half of destruction. But the newborn humanitarian international hardly stopped to reflect on this fact. New crises beckoned — most immediately, in Bangladesh — and who can know in advance whether saving lives will cost even more lives? The crisis caravan rolled on. Its mood was triumphalist, and to a large degree it remains so.

How is it that humanitarians so readily deflect accountability for the negative consequences of their actions? “Humanitarianism flourishes as an ethical response to emergencies not just because bad things happen in the world, but also because many people have lost faith in both economic development and political struggle as ways of trying to improve the human lot,” the social scientist Craig Calhoun observes in his contribution to a new volume of essays, “Contemporary States of Emergency,” edited by Didier Fassin and Mariella Pandolfi (Zone; $36.95). “Humanitarianism appeals to many who seek morally pure and immediately good ways of responding to suffering in the world.” Or, as the Harvard law professor David Kennedy writes in “The Dark Sides of Virtue” (2004), “Humanitarianism tempts us to hubris, to an idolatry about our intentions and routines, to the conviction that we know more than we do about what justice can be.”

Maren, who came to regard humanitarianism as every bit as damaging to its subjects as colonialism, and vastly more dishonest, takes a dimmer view: that we do not really care about those to whom we send aid, that our focus is our own virtue. He quotes these lines of the Somali poet Ali Dhux:

A man tries hard to help you find your lost camels.

He works more tirelessly than even you,

But in truth he does not want you to find them, ever.

Humanitarian Aid at Its Worst in Sierra Leone

Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “In Sierra Leone, a Dutch journalist named Linda Polman squeezed into a bush taxi bound for Makeni, the headquarters of the Revolutionary United Front rebels. In the previous decade, the R.U.F. had waged a guerrilla war of such extreme cruelty in the service of such incoherent politics that the mania seemed its own end. While the R.U.F. leadership, backed by President Charles Taylor, of Liberia, got rich off captured diamond mines, its Army, made up largely of abducted children, got stoned and sacked the land, raping and hacking limbs off citizens and burning homes and villages to the ground. But, in May, 2001, a truce had been signed, and by the time Polman arrived in Sierra Leone later that year the Blue Helmets of the United Nations were disarming and demobilizing the R.U.F. The business of war was giving way to the business of peace, and, in Makeni, Polman found that former rebel warlords — such self-named men as General Cut-Throat, Major Roadblock, Sergeant Rape Star, and Kill-Man No-Blood — had taken to calling their territories “humanitarian zones,” and identifying themselves as “humanitarian officers.” As one rebel turned peacenik, who went by the name Colonel Vandamme, explained, “The white men are soon gonna need drivers, security guards, and houses. We’re gonna provide them.” [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Colonel Vandamme called aid workers “wives”—“because they care for people,” according to Polman, and also, presumably, because they are seen as fit objects of manipulation and exploitation. Speaking in the local pidgin, Vandamme told Polman, “Them N.G.O. wifes done reach already for come count how much sick and pikin [children] de na di area.” Vandamme saw opportunity in this census. “They’re my pikin and my sick,” he said. “Anyone who wants to count them has to pay me first.”

This was what Polman had come to Makeni to hear. The conventional wisdom was that Sierra Leone’s civil war had been pure insanity: tens of thousands dead, many more maimed or wounded, and half the population displaced — all for nothing. But Polman had heard it suggested that the R.U.F.”s rampages had followed from “a rational, calculated strategy.” The idea was that the extreme violence had been “a deliberate attempt to drive up the price of peace.” Sure enough, Polman met a rebel leader in Makeni, who told her, “We’d worked harder than anyone for peace, but we got almost nothing in return.” Addressing Polman as a stand-in for the international community, he elaborated, “You people looked the other way all those years. . . . There was nothing to stop for. Everything was broken, and you people weren’t here to fix it.”

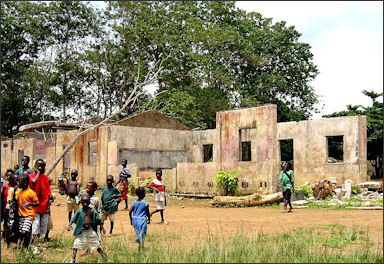

School destroyed by Sierra Leone Civil War In the end, he claimed, the R.U.F. had escalated the horror of the war (and provoked the government, too, to escalate it) by deploying special “cut-hands gangs” to lop off civilian limbs. “It was only when you saw ever more amputees that you started paying attention to our fate,” he said. “Without the amputee factor, you people wouldn’t have come.” The U.N.”s mission in Sierra Leone was per capita the most expensive humanitarian relief operation in the world at the time. The old rebel believed that, instead of being vilified for the mutilations, he and his comrades should be thanked for rescuing their country.

Is this true? Do doped-up maniacs really go a-maiming in order to increase their country’s appeal in the eyes of international aid donors? Does the modern humanitarian-aid industry help create the kind of misery it is supposed to redress? That is the central contention of Polman’s new book, “The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid?”. Three years after Polman’s visit to Makeni, the international Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Sierra Leone published testimony that described a meeting in the late nineteen-nineties at which rebels and government soldiers discussed their shared need for international attention. Amputations, they agreed, drew more press coverage than any other feature of the war. “When we started cutting hands, hardly a day BBC would not talk about us,” a T.R.C. witness said. The authors of the T.R.C. report remarked that “this seems to be a deranged way of addressing problems,” but at the same time they allowed that under the circumstances “it might be a plausible way of thinking.”

Polman puts it more provocatively. Sowing horror to reap aid, and reaping aid to sow horror, she argues, is “the logic of the humanitarian era.” Consider how Christian aid groups that set up “redemption” programs to buy the freedom of slaves in Sudan drove up the market incentives for slavers to take more captives. Consider how, in Ethiopia and Somalia during the nineteen-eighties and nineties, politically instigated, localized famines attracted the food aid that allowed governments to feed their own armies while they further destroyed and displaced targeted population groups. Consider how, in the early eighties, aid fortified fugitive Khmer Rouge killers in camps on the Thai-Cambodian border, enabling them to visit another ten years of war, terror, and misery upon Cambodians; and how, in the mid-nineties, fugitive Rwandan génocidaires were succored in the same way by international humanitarians in border camps in eastern Congo, so that they have been able to continue their campaigns of extermination and rape to this day.

And then there’s what happened in Sierra Leone after the amputations brought the peace, which brought the U.N., which brought the money, which brought the N.G.O.s. All of them, as Polman tells it, wanted a piece of the amputee action. It got to the point where the armless and legless had piles of extra prosthetics in their huts and still went around with their stubs exposed to satisfy the demands of press and N.G.O. photographers, who brought yet more money and more aid. In the obscene circus of self-regarding charity that Polman sketches, vacationing American doctors turned up, sponsored by their churches, and performed life-threatening (sometimes life-taking) operations without proper aftercare, while other Americans persuaded amputee parents to give up amputee children for adoption in a manner that seemed to combine aspects of bribery and kidnapping. Officers of the new Sierra Leone government had only to put out a hand to catch some of the cascading aid money.

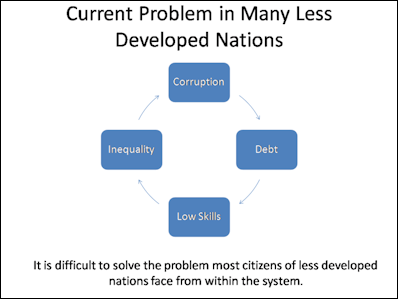

FlowChart for Problems in Less Developed Nations

Polman might also have found more heartening anecdotes and balanced her account of humanitarianism run amok with tales of humanitarian success: lives salvaged, epidemics averted, families reunited. But in her view the good intentions of aid — and the good that aid does — are too often invoked as excuses for ignoring its ills. The corruptions of unchecked humanitarianism, after all, are hardly unique to Sierra Leone. Polman finds such moral hazard on display wherever aid workers are deployed. In case after case, a persuasive argument can be made that, over-all, humanitarian aid did as much or even more harm than good.

“Yes, but, good grief, should we just do nothing at all then?” Max Chevalier, a sympathetic Dutchman who tended amputees in Freetown for the N.G.O. Handicap International, asked Polman. Chevalier made his argument by shearing away from the big political-historical picture to focus instead, as humanitarian fund-raising appeals do, on a single suffering individual — in this instance, a teen-age girl who had not only had a hand cut off by rebels but had then been forced to eat it. Chevalier wanted to know, “Are we supposed to simply walk away and abandon that girl?” Polman insists that conscience compels us to consider that option.

The scenes of suffering that we tend to call humanitarian crises are almost always symptoms of political circumstances, and there’s no apolitical way of responding to them — no way to act without having a political effect. At the very least, the role of the officially neutral, apolitical aid worker in most contemporary conflicts is, as Nightingale forewarned, that of a caterer: humanitarianism relieves the warring parties of many of the burdens (administrative and financial) of waging war, diminishing the demands of governing while fighting, cutting the cost of sustaining casualties, and supplying the food, medicine, and logistical support that keep armies going. At its worst — as the Red Cross demonstrated during the Second World War, when the organization offered its services at Nazi death camps, while maintaining absolute confidentiality about the atrocities it was privy to — impartiality in the face of atrocity can be indistinguishable from complicity.

Humanitarian Aid and the Genocide in Rwanda and the Congo

Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “In May of 1996, in the hill town of Kitchanga in the North Kivu province of eastern Congo (then still called Zaire), I spent a night in a dank schoolroom that had been temporarily set up as an operating room by surgeons from the Dutch section of Médecins Sans Frontières. A few days earlier, a gang from the U.N.-sponsored refugee camps for Rwandan Hutus — camps that were controlled by the killers, physically, politically, economically — had massacred a group of Congolese Tutsis at a nearby monastery. Members of the M.S.F. team had been patching up some of the survivors. A man with a gaping gunshot wound writhed beneath the forceps of a Belarusian doctor, chanting quietly—“Ay, yay, yay, yay, yay, yay” — before crying out in Swahili, “Too much sorrow.” [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Everyone knew that the Hutu génocidaires bullied and extorted aid workers, and filled their war chests with taxes collected on aid rations. Everybody knew, too, that these killers were now working their way into the surrounding Congolese territory to slaughter and drive out the local Tutsi population. (During my visit, they had even begun attacking N.G.O. vehicles.) In the literature of aid work, the U.N. border camps set up after the Rwandan genocide, and particularly the Goma camps, figure as the ultimate example of corrupted humanitarianism — of humanitarianism in the service of extreme inhumanity. It could only end badly, bloodily. That there would be another war because of the camps was obvious long before the war came.

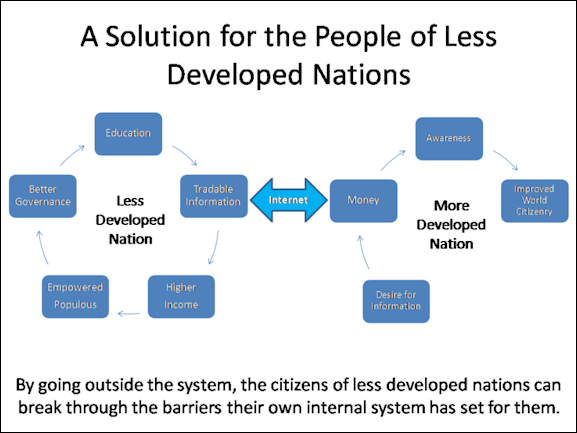

FlowChart, Solutions for Less Developed Nations

Aid workers were afraid, and demoralized, and without faith in their work. In the early months of the crisis, in 1994, several leading aid agencies had withdrawn from the camps to protest being made the accomplices of génocidaires. But other organizations rushed to take over their contracts, and those who remained spoke of their mission as if it had been inscribed in stone at Mt. Sinai. They could not, they said, abandon the people in the camps. Of course, that’s exactly what the humanitarians did when the war came: they fled as the Rwandan Army swept in and drove the great mass of people in the camps home to Rwanda. Then the Army pursued those who remained, fighters and noncombatants, as they fled west across Congo. Tens of thousands were killed, massacres were reported — and this slaughter was the ultimate price of the camps, a price that is still being paid today by the Congolese people, who chafed under serial Rwandan occupations of their country, and continue now to be preyed upon by remnant Hutu Power forces.

Sadako Ogata, who ran the U.N. refugee agency in those years, and was responsible for all the camps in Congo, wrote her own self-exculpating book, “The Turbulent Decade,” in which she repeatedly falls back on the truism “There are no humanitarian solutions to humanitarian problems.” She means that the solution must be political, but, coming from Ogata, this mantra also clearly means: no holding humanitarianism accountable for its consequences. One of Ogata’s top officers at the time said so more directly, when he summed up the humanitarian experience of the Hutu Power-controlled border camps and their aftermath with the extraordinary Nixonian formulation “Yes, mistakes were made, but we are not responsible.”

Humanitarian Aid and Failed State Politics

help for Somalia drought Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker, “The Crisis Caravan” is the latest addition to a groaning shelf of books from the past fifteen years that examine the humanitarian-aid industry and its discontent. Polman leans heavily on the seminal critiques advanced in Alex de Waal’s “Famine Crimes” and Michael Maren’s “The Road to Hell”; on Fiona Terry’s mixture of lament and apologia for the misuse of aid, “Condemned to Repeat”; and on David Rieff’s pessimistic meditation on humanitarian idealism, “A Bed for the Night.” All these authors are veteran aid workers, or, in Rieff’s case, a longtime humanitarian fellow-traveller. Polman carries no such baggage. She cannot be called disillusioned. In an earlier book, “We Did Nothing,” she offered a prosecutorial sketch of the pathetic record of U.N. peacekeeping missions. Then, as now, her method was less that of investigative reporting than the cumulative anecdotalism of travelogue pointed by polemic. Her style is brusque, hardboiled, with a satirist’s taste for gallows humor. Her basic stance is: J’accuse. [Source: Philip Gourevitch, The New Yorker, October 11, 2010]

Polman takes aim at everything from the mixture of world-weary cynicism and entitled self-righteousness by which aid workers insulate themselves from their surroundings to the deeper decadence of a humanitarianism that paid war taxes of anywhere from fifteen per cent of the value of the aid it delivered (in Charles Taylor’s Liberia) to eighty per cent (on the turf of some Somali warlords), or that effectively provided the logistical infrastructure for ethnic cleansing (in Bosnia). She does not spare her colleagues in the press, either, describing how reporters are exploited by aid agencies to amplify crises in ways that boost fund-raising, and to present stories of suffering without political or historical context.

Journalists too often depend on aid workers — for transportation, lodging, food, and companionship as well as information — and Polman worries that they come away with a distorted view of natives as people who merely suffer or inflict suffering, and of white humanitarians as their only hope. Most damningly, she writes: “Confronted with humanitarian disasters, journalists who usually like to present themselves as objective outsiders suddenly become the disciples of aid workers. They accept uncritically the humanitarian aid agencies’ claims to neutrality, elevating the trustworthiness and expertise of aid workers above journalistic skepticism.”

Maren and de Waal expose more thoroughly the ignoble economies that aid feeds off and creates: the competition for contracts, even for projects that everyone knows are ill-considered, the ways in which aid upends local markets for goods and services, fortifying war-makers and creating entirely new crises for their victims. Worst of all, de Waal argues, emergency aid weakens recipient governments, eroding their accountability and undermining their legitimacy. Polman works in a more populist vein. She is less patient in building her case — at times slapdash, at times flippant. But she is no less biting, and what she finds most galling about the humanitarian order is that it is accountable to no one. Moving from mess to mess, the aid workers in their white Land Cruisers manage to take credit without accepting blame, as though humanitarianism were its own alibi.

Improving Foreign Aid

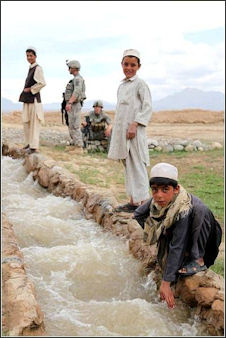

irrigation canal in Afghanistan Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, We must change the way the world goes about the business of providing development aid. We need a genuine partnership, in which developing countries take the lead, determining what they most acutely need and how best to use it. Weak capacity to absorb aid on the part of recipient countries is no excuse for donor-driven and donor-directed assistance. The aim should be to help create that capacity. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, September 14, 2010]

Doing so would serve donors’ interest as well. Aligning their assistance with national development strategies and structures, or helping countries devise such strategies and structures, ensures that their aid is usefully spent and guarantees the sustainability of their efforts. Donors should support an education policy rather than build a photogenic school; aid a health campaign rather than construct a glittering clinic; or do both — but as part of a policy or a campaign, not as stand-alone projects.

Trade is the other key area. In contrast to aid, greater access to the developed world’s markets creates incentives and fosters institutions in the developing world that are self-sustaining, collectively policed, and more consequential for human welfare. Many countries are prevented from trading their way out of poverty by the high tariff barriers, domestic subsidies, and other protections enjoyed by their rich-country competitors.

The European Union’s agricultural subsidies, for example, are high enough to permit every cow in Europe to fly business class around the world. What African farmer, despite his lower initial costs, can compete?

The onus is not on developed countries alone. Developing countries, too, have made serious commitments to their own people, and the primary responsibility for fulfilling those commitments is theirs. But Goal 8 assured them that they would not be alone in this effort. Unless that changes, the next five years will be a path to failure.

Small Global Taxes to Help the Poor?

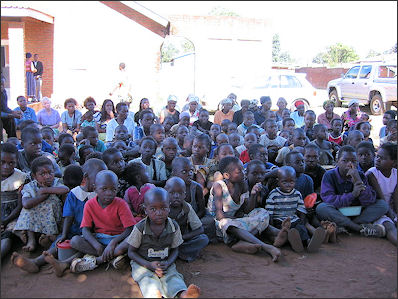

Orphans in Malawi France's Bernard Kouchner, Japan's Katsuya Okada, and Belgium's Charles Michel say that innovative financing to fund development projects is needed to lift up the world's poorest people. They wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “Actual measures for innovative financing include, among others, taxes on airline tickets to finance access to essential medicines through UNITAID, a fund hosted by WHO, and bonds secured by government pledges to finance for immunization (GAVI). Such measures have mobilized resources to fight against the three major infectious diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria) and to scale up immunization programs. They have produced remarkable results. Moreover, efforts to encourage voluntary contributions such as donations by citizens, consumers, and companies have been made. [Source: Bernard Kouchner, Katsuya Okada, Charles Michel,Christian Science Monitor, August 31, 2010, at that time Bernard Kouchner was the foreign minister of France, Katsuya Okada was the foreign minister of Japan, and Charles Michel was the development cooperation minister of Belgium]

The Doha Conference in November 2008 called on the world to change the dimensions of innovative development financing. New instruments that are based on global activities are becoming available to us — broad-based financing that could, through miniscule contributions repeated numerous times, change the dimensions of hope, if properly coordinated.

As a concrete step toward this aim, we established the Taskforce on International Financial Transaction for Development in October 2009 with the objective of coming up with a shared analysis of what is feasible, and making concrete, realistic proposals. A report by the task force assesses technical issues in a comprehensive manner and provides estimates on tax revenues. The report mentions that a levy of five cents for each $1,000 exchanged could bring in more than $30 billion per year. It supplements and updates other analyses carried out regularly over the years by the UN, the European Commission, and the Landau Report. It also offers us common ground to discuss innovative financing, and has started to play a significant role in evoking greater international discussion.

Toward 2015, the target year of the MDGs, we must provide safe water for a billion people; enough food for a billion people; appropriate treatment for major pandemics; education for children. For approaching these goals, we should not be inward-looking. We need to have sympathy, as fellow human beings, for people who are struggling throughout the world and extend support for developing countries. We cannot just only rely on the traditional overseas DA. The real challenge today is designing an innovative mechanism based on strict governance and allocation criteria. It is time to act, and to do it in an exemplary fashion.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012