VILLAGE BATHROOMS AND TOILETS

old toilet in Beijing More than 2.6 billion people around the world don't have access to safe sanitation. Instead of using toilets connected to sewer lines, most leave their waste on the ground or in a ditch or pit. The result is unsightly, unsanitary and contributes to illness. Some 1.5 million children die each year from diarrhea-related diseases, often connected to poor sanitation. Many development experts believe most of these deaths could be prevented with proper sanitation, safe drinking water and improved hygiene.

According to a United Nations report, half the world's people don't have access to toilet or a clean latrine People often relieve themselves in the bushes or in a field. Only 30 percent of the world uses toilet paper. Alternatives include hands, water, sand, small rocks, mud, leaves, rope and seaweed.

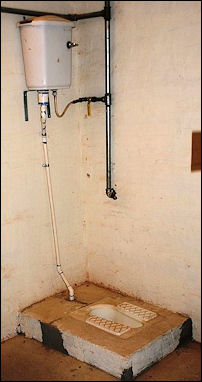

A typical bathroom is a shed-like outhouse in back of the house with cinder blocks walls and a metal door and roof. The toilet may be a Wester-style model but more often that not it is a latrine or a hole in the ground surrounded by concrete. People sit on makeshift boxes with a hole or they squat instead of sit. If there is a flushing system it is more often than not a ladle and a bucket of water. Most guesthouses and hotels used by foreigners have Western style toilets.

Toilets can be very wasteful. The water from one flush of a toilet is equal to what an average person uses each day in the 30 world’s poorest countries.

American-style soft toilet paper is bad for the environment environmentalists say. To make it soft and fluffy requires chopping down trees, in some cases from virgin rain forests in Brazil and Indonesia. The long fibers from old trees produce a smoother and more supple web and this translates to softer toiler paper. Toilet paper made with recycled paper — which has shorter fibers — is stiffer and courser. Environmental groups such as Greenpeace have been trying to get toilet paper makers like Kimberly-Clark to use more recycled paper in their products. In recent years executives with the company have said they will try but have their customers to worry about.

squatting in the AndesIn Indonesia and other places in Southeast Asia and the tropical world many people take a “mandi” — a “shower” with cold water, using a ladle-like scooper and a bucket or basin. In some places the mandi consists of a cement container filled with water and a large plastic ladle or cut up detergent bottle used for scooping up water. Often hot water is not available and when it is it is often heated in a pot in the kitchen and brought in a bucket.

Where the weather is hot a cold shower is often preferable to a hot one anyway. In some places a mandi is a big bucket. In other places it is a square concrete trough. When taking a mandi first fill up the basin, bucket or trough with water, usually from a tap, and dip the ladle or scooper in the water and water and then douse yourself using the ladle. It is a good idea to run water from the tap while you are taking a mandi to make sure there is enough water. It is good etiquette and leave water in the basin for the person who takes a mandi after you. Standing in the basin is unacceptable behavior.

Lack of Toilets and Sanitation in the Developing World

Two out of every five people in the world have no access to safe toilets. Rather than using flush toilets they use open pits or latrines that flush waste into the streets or simply go in a nearby field. Places with sewers often have no waste-water treatment facilities and sewage is dumped directly into water supplies from which people draw their water.

According to the United Nations poor sanitation kills 1.5 million children a year. Most die of diarrhea from drinking contaminated water. Diarrhea is the world’s No.2 leading killer of children. Poor sanitation is also blamed for the spread of intestinal worms, pneumonia and cholera.

Studies have shown that providing clean water offers tremendous benefits. Health costs go down. People live longer, stay healthier and are more productive. But often there is little political will to invest in sanitation.

Jack Sim, a retired real estate entrepreneur and founder of the World Toilet Organization, has made it his goal to improve health in the developing world by introducing more toilets to villages. He said the biggest obstacle that needs to be overcome is the embarrassment factor. He told Time, “It’s a question of marketing toilets as a status symbol. I want people to aspire to owning a toilet.” As a starting point he has been promoting ecologically-sound latrines, which can cost as little as $10 a piece. Sim is also working with fertilizer businesses and engineers on effective ways to collect waste and use it to grow crops and generate biogas for cooking stoves.

Peace Corps volunteers have taught people how to build latrines with 112 mud bricks, at least 50 feet downhill from their homes.

Cleaning Pit Latrines by Hand and Sanitation for the Poor in Developing World Cities

squat toilet in Iraq

Reporting from Nairobi, Kenya, Donna Blankinship and Tom Odula wrote in Associated Press, “At dawn every Sunday, Joseph Irungu leads an army of 50 men pushing hand carts fitted with old 42-gallon oil drums through the narrow alleyways of one of Kenya's most populous slums. With their bare hands, they use buckets to draw the feces from the pit latrines in Korogocho, fill the oil drums and push them to a river to deposit the waste. Every trip leaves the men with splotches of sewage on their faces and hands. [Source: Donna Blankinship and Tom Odula, Associated Press, July 19, 2011]

Irungu has been leading this sanitation brigade since 1998, when the Nairobi City Council refused his request to drain the pit latrine at his plot of rental houses. "It was too much," he said. "I had to do something, so I picked up a bucket and drained it myself. I realize that many other landlords were facing similar problems and a business opportunity presented itself."

Irungu, 47, says the main problem in communities like the Korogocho slum is the lack of sewage facilities and access to water. He has already seen a positive impact from his efforts, including a decrease in cholera outbreaks. "This place used to smell because people would go the toilet in (plastic) bags and throw them in the streets because they could not go to the toilets which were overflowing with waste," he said.

Paying to use clean toilets and water is an extra expense many slum dwellers cannot afford, so they end up using the dirty facilities that can expose them to diseases. The use of a toilet costs about two cents, or two Kenyan shillings. If better toilets are introduced Irungu will lose his business, but he says he feels guilty disposing waste in a river. He says he has no alternative. The slum was built on rocky land, so many landlords dig shallow pit latrines that fill quickly because they are sometimes used by as many as 30 people.

For every latrine drained, Irungu takes home about $2, a solid income in an area where many residents earn less that $1 a day. Through this work he has been able to educate his five children, he said. Korogocho resident Veronica Wanjiru, 29, who has two children aged 7 and 11, says cleanliness is a problem. "Most of the tenants choose to use a donor-funded toilet facility which you pay 2 shillings," she said. "Many of us cannot afford this fee so our children use potties until they are even 14 years or for those who cannot afford that they use paper bags which are then thrown into a ditch."

Wanjiru said that if her family used the public toilet twice a day, it would cost her 12 shillings (13 cents), which she cannot afford. Instead, her children leave their waste in a portable, self-contained toilet chair. She dumps its contents into a ditch. "I know that disposing of feces in the ditch is bad but I have no choice. I have no toilet. I don't have a steady job," said Wanjiru, who washes clothes for a living. "Disposing the feces in the ditch is bad because that is where my children play."

Poor Sanitation and Health Problems Among the Poor

Primitive toilet in Indonesia

Reporting from southern Ethiopia, Tina Rosenberg wrote in National Geographic, “Much of the cash they do have goes for four- to eight-dollar visits to the village health clinic to cure the boys of diarrhea caused by bacteria and parasites they regularly get from the lack of proper hygiene and sanitation and from drinking untreated river water. At the clinic, nurse Israel Estiphanos said that in normal times 70 percent of his patients suffer waterborne diseases — and now the area was in the midst of a particularly severe outbreak. Next to the clinic a white tent had arisen for these patients. By my next visit, Estiphanos was attending to his patients wearing high rubber boots. [Source: Tina Rosenberg, National Geographic, April 2010]

Sixteen miles away at the district health center in Konso's capital, almost half the 500 patients treated daily were sick with waterborne diseases. Yet the health center itself lacked clean water. On the walls of the staff rooms were posters listing the principles of infection control. But for four months a year, the water feeding their taps would run out, said Birhane Borale, the head nurse, so the government would truck in river water. "We use water then only to give to patients to drink or swallow medicine," he said. "We have HIV patients and hepatitis B patients. They are bleeding, and these diseases are easily transmittable — we need water to disinfect. But we can clean rooms only once a month."

Even medical personnel weren't in the habit of washing hands between patients, as working taps existed at only a few points in the building — most of the examining rooms had taps, but they were not connected. Tsega Hagos, a nurse, said she had gotten spattered with blood taking out a patient's IV. But even though there was water that day, she had not washed her hands afterward. "I just put on a different glove," she said. "I wash my hands when I get home after work."

Encouraging hygiene is a challenge. Wako Lemeta is one of two hygiene promoters whom WaterAid has trained in Foro. Lemeta, rather shy and poker-faced, stops by Binayo's house and asks her husband, Guyo Jalto, if he can check their jerry cans. Jalto leads him to the hut where they are stored, and Lemeta uncovers one and sniffs. He nods approvingly; the family is using WaterGuard, a capful of which purifies a jerry can of drinking water. The government began to hand out WaterGuard at the beginning of the recent outbreak of disease. Lemeta also checks if the family has a latrine and talks to villagers about the advantages of boiling drinking water, hand washing, and bathing twice a week.

Many people have embraced the new practices. Surveys say latrine use has risen from 6 to 25 percent in the area since WaterAid began work in December 2007. But it is a struggle. "When I tell them to use soap," Lemeta explains, "they usually tell me, 'Give me the money to buy it.' "

Sanitation and Clean Water Declared 'Human Right’ by the U.N

In July 2010, the U.N. General Assembly declared access to clean water and sanitation a "human right" in a resolution that more than 40 countries including the United States didn't support. The resolution adopted by the 192-member world body expresses deep concern that an estimated 884 million people lack access to safe drinking water and more than 2.6 billion people do not have access to basic sanitation. U.N. anti-poverty goals adopted by world leaders in 2000 call for the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation to be cut in half by 2015. [Source: Associated Press, July 29, 2010]

AP reported: “The non-binding resolution, sponsored by Bolivia, was approved by a vote of 122-0 with 41 abstentions including the United States and many Western nations though Belgium, Italy, Germany, Spain and Norway supported it. Bolivia's representative said many rights have been recognized including the rights to health, life, and education. He said the Bolivian government introduced a resolution on the right to adequate water and sanitation because contaminated water causes more than 3.5 million deaths every year - more than any war.

Explaining why the U.S. didn’t support the resolution, U.S. diplomat John Sammis told the General Assembly that the United States "is deeply committed to finding solutions to our water challenges," but he said the resolution "describes a right to water and sanitation in a way that is not reflective of existing international law."

The resolution calls the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation "a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights." It calls on U.N. member states and international organizations to provide funding, technology and other resources to help poorer countries "scale up" efforts to provide clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all people.

On the U.N. Millennium Development Goals of cutting the the proportion of people without access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation cut in half by 2015, the latest U.N. assessment on progress toward achieving the goals said that "with half the population of developing regions without sanitation, the 2015 target appears to be out of reach" but it said "the world is on track to meet the drinking water target, though much remains to be done in some regions" especially sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania.

Bill Gates Foundation Gives $42 Million to Improve Toilets

In July 2011 at the AfricaSan Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced $42 million in grants to encourage innovation in the capture, storage and repurposing of waste as an energy resource. More than 2.6 billion people around the world don't have access to safe sanitation and some 1.5 million children die each year from diarrhea-related diseases, often caused by poor sanitation.

AP reported, “Because the Gates Foundation believes most of these deaths could be prevented with proper sanitation, safe drinking water and improved hygiene, foundation officials are in Africa this week to launch this new initiative. The foundation is focusing on toilets and sanitation, in part, because it's the least attractive part of world development, said Frank Rijsberman, director of the foundation's water, sanitation and hygiene initiative. "It's almost taboo. ... It's not exactly a subject in polite conversation," he said.[Source: Donna Blankinship and Tom Odula, Associated Press, July 19, 2011]

Before the end of the year, the foundation hopes to have 50 to 60 groups working on ideas for the next generation of toilets, which should run without water or electricity and not be attached to a sewer system. Rijsberman said they're aiming for a toilet that is useful in more than one way, such as one that turns waste into something that can be used for energy. If all goes as planned, in three to five years there will be a handful of solutions that will lead to products or innovations to serve tens of millions of people, he said.

Fertilizer-Producing Ecological Sanitation Toilet

A Japanese housewife-run NGO called NICCO has introduced an "ecological sanitation toilet," which converts human waste into safe and effective fertilizer, in poor countries like Malawi. Asako Kisui wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The toilet is designed to use separate tanks--one for urine that can be immediately used for fields if it is diluted with water and the other for solid waste that is likely to include pathogens. The solid waste can be converted into fertilizer through a process that includes mixing it with ash to make it alkaline to kill the pathogens, and drying it for about six months. [Source: Asako Kisui, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 26, 2011]

new toilet in China In Malawi the toilets were not used effectively by local people at first. They sometimes used the toilets as storage sheds as they had no habit of using human waste to make fertilizer. To convince Malawian farmers of the effectiveness of fertilizer derived from human waste, NICCO showed them a comparison of corn crop yields in a field with such fertilizer and a field without it. Crop yields in the fertilized field were 2.3 times bigger than those in the unfertilized field. Seeing the results, an increasing number of farmers began to use the toilet.

A total of 666 toilets were then constructed in the country. The Malawian government praised the toilets and began to investigate benefits of using them, according to NICCO. Morie Otoyo, 33, a NICCO staffer stationed in the country, said: "Villagers are pleased, saying things like, 'We could buy new cattle, as our cash income has increased.' Compared with the time when people simply dug holes to use as toilets, the number of dysentery and cholera infections has decreased."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Julie Chao

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012