ANCIENT GREEK MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE

Wedding procession Greek marriages were usually arranged by parents and families. Men tended to marry relatively late, around 30, and women married when they were relatively young, around 14..

It was common for well-traveled, high-status middle aged man to marry a virgin of 16. The main duty of the new bride was to produce children. Menader wrote: "I give you this woman (my daughter) for the ploughing of legitimate children."

As the years wore on, married life lost some of its appeal. One Roman magistrate described marriage as "legalized hardship" and the historian Plautus once said to his wife: "Enough is enough, woman. Save your voice. You'll need it to nag me tomorrow."** Marriages who often arranged and men sought satisfaction with courtesans or male lovers. On Marriage, the Greek comic poet Susarion wrote (c. 440 B.C.): “Hear, O ye people! Susarion says this, the son of Philinus, the Megarian, of Tripodiscus: women are an evil; and yet, my countrymen, one cannot set up house without evil; for to be married or not to be marries is alike bad. [Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

The lyric poet Theognis wrote (c. 550 B.C.): “Rams and asses, Cyrnus, and horses, we choose of good breed, and wish them to have good pedigrees; but a noble man does not hesitate to wed a baseborn girl if she bring him much money; nor does a noble woman refuse to be the wife of a base but wealthy man, but she chooses the rich instead of the noble. For they honor money; and the noble weds the baseborn, and the base the highborn; wealth has mixed the race. So, do not wonder, Polypaides, that the race of the citizens deteriorates, for the bad is mixed with the good.”

Divorces were fairly common and easy to get in ancient Greece and Rome. Providing legal grounds for divorce was not necessary. A man could divorce his wife simply if he didn't like her anymore. All he had to was get a document from a magistrate. There is no record of one ever being denied.

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Ancient Greek Weddings

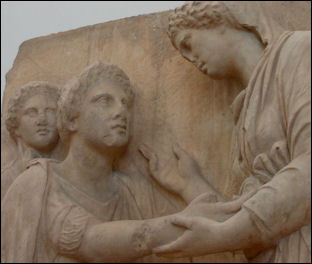

family scene on funerary stele It is likely that many ancient Greek brides and grooms never even met each other before their wedding day. Greek historian Ian Jenkins speculates that for some young brides the shock of being taken away from home and placed in a house with a complete stranger was "a frightening, even traumatic, experience." To symbolize the passing of her youth, on the day before her wedding, the bride sacrificed all of her toys to the virgin goddess Artemis and took a ritual bath with perfumed water from a vessel depicting a marriage scene and then swore fealty to Demeter, the goddess or agriculture and married women.| [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

On the wedding day itself, rich couples rode in a chariot to the groom's house, where the ceremony was held; poor couples were taken in an ox or mule cart. Before she was picked up the bride often pleaded with her mother to be hidden somewhere. When the couple arrived at the groom's house they were showered with dates, figs, nuts and small coins by the groom's family. After some verses were recited in a small ceremony, the couple was ushered into a bedroom where the marriage was consummated. It wasn't until the next day that the two families got together for a big wedding party. Presents, which were given only to the bride, were held in a trust so that if her husband died prematurely (not an uncommon occurrence) she would have a way of taking care of herself.||

Ancient Greek and Roman Wedding Customs

Greek brides wore veils. In Aphrodisias it was a common custom for women to prostitute themselves in the Temple of Aphrodite before they were married. The money they earned was donated to the goddess. Women who didn't want to go along with this could sacrifice their hair instead. Aphrodite was a metamorphosed form of the Babylonian fertility goddess, Ishtar, who Julius Caesar, Romulus and Remus, and the Trojan Aeneashave were all said to have descended from. [Source: Kenan T. Erim, National Geographic, October 1981 **]

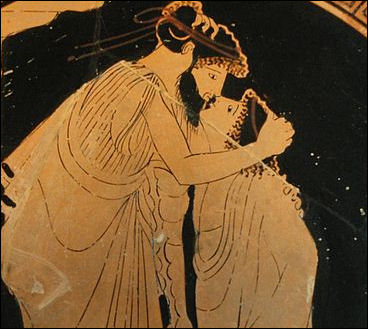

a kiss In Sparta, the bride was usually kidnapped, her hair was cut short and she dressed as a man, and laid down on a pallet on the floor. "Then," Plutarch wrote, "the bride groom...slipped stealthily into the room where his bride lay, loosed her virgin's zone, and bore her in his arms to the marriage-bed. Then after spending a short time with her, he went away composedly to his usual quarters, there to sleep with the other men."||

At Roman weddings, guests sang bawdy songs, boys dived for nuts as a symbol of fertility and rings were placed on the bride's middle finger of her left hand. A nerve, Roman believed, ran from the middle finger to the heart.**

The tradition of carrying the bride across the threshold began with the Romans. The groom first went into the house to light the hearth while the bride smeared oil and grease around the doorway as a sign of good luck. To ensure that the bride wouldn't do anything like stumble, bringing bad luck to the house, she was carried into the house left foot first. The only difference between the way the Roman's did it and the way we do it today is that slaves carried her into the house not her husband.**

The world's first known stag parties were held by the Spartans. At these parties Spartan grooms were given a feast by their friends and comrades the night before his wedding. There was no doubt singing, drinking and lewd jokes. The ritual marked the end of bachelorhood and the groom assured his comrades he would remain loyal to them and not leave them.

Wedding Songs from Ancient Greece

Aristophanes, “Wedding Song to Hymenaios,” c. 400 B.C.

Zeus, that god sublime,

When the Fates in former time,

Matched him with the Queen of Heaven

At a solemn banquet given,

Such a feast was held above,

And the charming God of Love

Being present in command,

As a bridegroom took his stand

With the golden reins in hand,

Hymen, Hymen, Ho!

[Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260]

alabastron with a courtship scene

Theocritus, “The Bridal Hymn,” c. 250 B.C.

Slumber so soon, sweet bridegroom?

Are you overfond of sleep?

Or have you leaden-weighted limbs?

Or have you drunk too deep

When you did fling come to your lair?

Betimes you should have sped,

If sleep were all your purpose,

unto your bachelor's bed,

And left her in her mother's arms

To nestle and to play,

A girl among her girlish mates,

Till deep into the day---

For not alone for this night,

Nor for the next alone,

But through the days and through the years

You have her for your own.

“Sleep on, and love and longing

Breathe in each other's breast,

But fail not when the morn returns

To rouse you from your rest;

With dawn shall we be stirring,

When, lifting high his fair

And feathered neck, the earliest bird

To clarion to the dawn is heard.

O! God of brides and bridals,

Sing, 'Happy, happy pair!'

“Anacreon, The Morning Nuptial Chant", c. 400 B.C.

Aphrodite, queen of goddesses;

Love, powerful conqueror;

Hymen, source of life:

It is of you that I sing in my verses.

'Tis of you I chant, Love, Hymen, and Aphrodite.

Behold, young man, behold your wife!

Arise, O Straticlus, favored of Aphrodite,

Husband of Myrilla, admire your bride!

Her freshness, her grace, her charms,

Make her shine among all women.

The rose is queen of flowers;

Myrilla is a rose midst her companions.

May you see grow in your house a son like to you!

Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) On Divorce and Adoption

The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“IV. If a husband and wife be divorced, she shall have her own property that she came with to her husband, and the half of the income if it be from her own property, and whatever she has woven, the half, whatever it may be, and five staters, if her husband be the cause of her dismissal; but if the husband deny that he was the cause, the judge shall decide. . .

“VI. If a woman bear a child while living apart from her husband after divorce, she shall have it conveyed to the husband at his house, in the presence of three witnesses; if he do not receive the child, it shall be in the power of the mother to bring up or expose. . .

“XVII. Adoption may take place whence one will; and the declaration shall be made in the market-place when the citizens are gathered. If there be no legitimate children, the adopted shall received all the property as for legitimates. If there be legitimate children, the adopted son shall receive with the males the adopted son shall have an equal share. If the adopted son shall die without legitimate children, the property shall return to the pertinent relatives of the adopter. A woman shall not adopt, nor a person under puberty.

Ancient Greek Families and Men

In ancient Greece and Rome inheritance was transferred from father to oldest son. A typical household consisted of a wife, children, unmarried brothers and sisters and slaves.

Upper class Greek men have been characterized as creatures who worked out in gym in the morning and discussed philosophy and democracy in the afternoon.

Aristotle wrote that men were more perfect embodiments of human beings than women and it was natural that they live longer. Priam of Troy had 60 children.

Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) on Property and Inheritance

The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“V. If a man die, leaving children, if his wife wish, she may marry, taking her own property and whatever her husband may have given her, according to what is written, in the presence of three witnesses of age and free. But if she carry away anything belonging to her children she shall be answerable. And if he leaves her childless, she shall have her own property and whatever she has woven, the half, and of the produce on hand in possession of the heirs, a portion, and whatever her husband has given her as is written. If a wife shall die childless, the husband shall return to her heirs her property, and whatever she has woven the half, and of the produce, if it be from her own property, the half. If a female serf be separated from a male serf while alive or in case of his death, she shall have her own property, but if she carry away anything else she shall be answerable.

“VII. The father shall have power over his children and the division of the property, and the mother over her property. As long as they live, it shall not be necessary to make a division. But if a father die, the houses in the city and whatever there is in the houses in which a serf residing in the country does not live, and the sheep and the larger animals which do not belong to the serf, shall belong to the sons; but all the rest of the property shall be divided fairly, and the sons, howsoever many there be, shall receive two parts each, and the daughters one part each. The mother's property also shall be divided, in case she dies, as is written for the father's. And if there should be no property but a house, the daughters shall receive their share as is written. And if a father while living may wish to give to his married daughter, let him give according to what is written, but not more. . .

“X. As long as a father lives, no one shall purchase any of his property from a son, or take it on mortgage; but whatever the son himself may have acquired or inherited, he may sell if he will; nor shall the father sell or pledge the property of his children, whatever they have themselves acquired or succeeded to, nor the husband that of his wife, nor the son that of the mother. . . If a mother die leaving children, the father shall be trustee of the mother's property, but he shall not sell or mortgage unless the children assent, being of age; and if anyone shall otherwise purchase or take on pledge the property, it shall still belong to the children; and to the purchaser or pledgor the seller or pledgee shall pay two-fold the value in damages. But if he wed another, the children shall have control of the mother's property.

“XIV. The heiress shall marry the brother of the father, the eldest of those living; and if there be more heiresses and brothers of the father, they shall marry the eldest in succession. . . But if he do not wish to marry the heiress, the relatives of the heiress shall charge him and the judge shall order him to marry her within two months; and if he do not marry, she shall marry the next eldest. If she do not wish to marry, the heiress shall have the house and whatever is in the house, but sharing the half of the remainder, she may marry another of her tribe, and the other half shall go to the eldest. . .

“XVI. A son may give to a mother or a husband to a wife 100 staters or less, but not more; if he should give more, the relatives shall have the property. If anyone owing money, or under obligation for damages, or during the progress of a suit, should give away anything, unless the rest of his property be equal to the obligation, the gift shall be null and void. One shall not buy a man while mortgaged until the mortgagor release him. .

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018