SEX IN ANCIENT GREECE

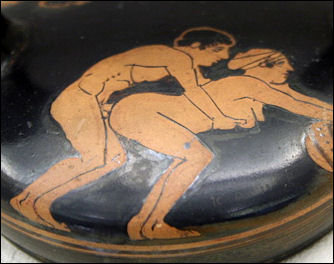

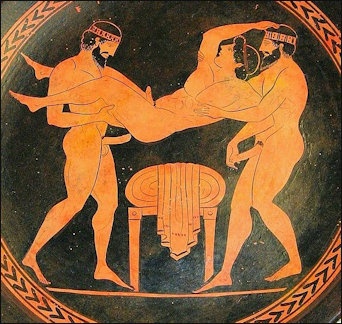

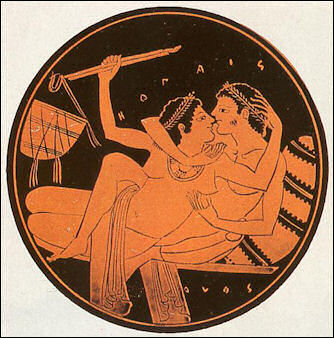

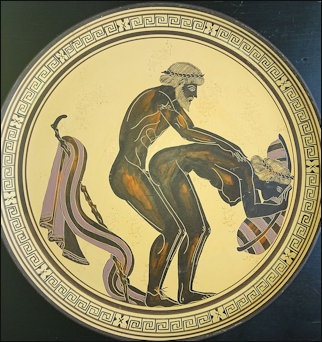

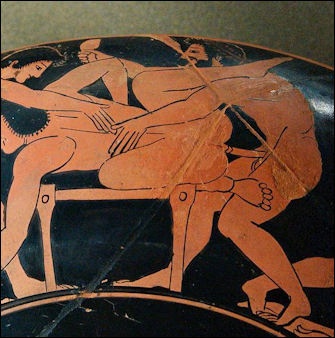

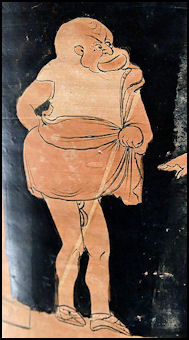

The Greeks gave sexual matters a fair amount of attention. Men raised monuments to their genitalia and had sex with the sons of their friends. Some had slave lovers. Naughty images were featured on vases and drinking cups. Sexual themes were common in Greek drama and actors routinely wore conspicuously short costumes with massive woolen phalluses hanging out the bottom. The word "ecstacy comes from the Greek word “ ekstasis” , which means to "stand forth naked."

The Greek gods realized that sex was the driving force behind all things. According to Herodotus, “the Athenians were first to make statues of Hermes with an erect phallus. Hippocrates was one of the first to advise men to preserve their semen to boost vitality. The Greek poet Hero wrote in the 4th century B.C. that a man's sex drive decreases in the late summer when "goats are the fattest" and "the wine tastes best."

The Greeks believed that the root of purple-flowered mandrake was an aphrodisiac. The root is shaped like a pair of human legs. The Romans and Greeks regarded garlic and leeks as aphrodisiacs. Truffles, artichokes and oysters were also associated with sexuality. Anise-tasting fennel was popular with Greeks who thought it made a man strong. Romans thought it improved eyesight.

Ray Tannahill wrote in the “ History of Sex” : "Masturbation, to the Greeks, was not a vice but a safety valve, and there are numerous literary references to it...Miletus, a wealthy commercial city on the coast of Asia Minor, was the manufacturing and exporting center of what the Greeks called the “ olisbos” , and later generations, less euphoniously, the dildo...The imitation penis appears in Greek times to have been made either of wood or pressed leather and had to be liberally anointed with olive oil before use...Among the literary relics of the third century B.C., there is a short play consisting of a dialogue between two young women, Metro and Coritto, which begins with Metro trying to borrow Coritto's dildo. Coritto, unfortunately, his lent it to someone else, who has in turn lent it to another friend."

For women sex was used as a form of power. In Aristophanes’s “ Lysieria” the heroine leads the women of Athens in a sex strike in which wives refuse to sleep with their husbands to get even with the dominate male class. The strike paralyzes the city and the women seize the Acropolis and the treasure of the Parthenon. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Book: “ Courtesand and Fishcakes: the Consuming Passions of Classical Athens” by James Davidson (St. Martins Press, 1998)

Sex and Religion in Ancient Greece

priestess of Delphi by Collier

Greek pilgrims are said to have visited a temple in Corinth dedicated to Aphrodite and cavorted with prostitute-priestesses there. Strabo wrote in 2 B.C.: "The temple of Aphrodite was so rich that it employed more than a thousand hetairas, whom both men and women had given to the goddess. Many people visited the town on account of them, and thus these hetairas contributed to the riches of the town: for the ship captains frivolously spent their money there, hence the saying: 'The voyage to Corinth is not for every man'. (The story goes of a hetaira being reproached by a woman for not loving her job and not touching wool, and answering her: 'However you may behold me, yet in this short time I have already taken down three pieces'.)"

The Greek creation story emphasizes the creation of gods not the creation of the Earth and has a lot of sex in it. The Greeks believed that love and sex existed at the beginning of creation along with the Earth, the heavens, and the Underworld . Chaos, apparently the first Greek celestial being, was a goddess who beget "Gaia, the broad-breasted" and "Eros, the fairest of the deathless gods." Chaos also gave birth to Erebos and black Night. These two offspring mated and gave birth to Ether and Day. They in turn gave birth to the Titans.

The Titans existed before the gods. They were the sons of the heaven and earth. Cronus , the father of Zeus was one of the Titans. He castrated his father, Uranus, and out his blood emerged the Furies, the Giants and the Nymphs from the Ash Trees. Aphrodite arose from the discarded genitals. The god's lovemaking positions were also a little weird. Tartarus, the goddess of the Underworld , made love with Typhoeus while he was one her shoulders with his hundred snake heads "licking black tongues darting forth." [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

Sex and Literature in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek literature is filled with sex, violence and scandal. Some of the most famous works by Aristophanes — including “The Birds” , “Lysistrata” and especially “Women at the Thesmoporia” “are filled with obscenities and sexual innuendos. The reasons why some of the works are relatively clean today — and more boring than the otherwise might be — is that many of the translations were done by Victorian era Britons. Greek dramas often featured liberal use actors of with giant phalluses and references to homosexuality. In “ Clouds” Aristophanes wrote: "How to be modest, sitting so as not to expose his crotch, smoothing out the sand when he arose so that the impress of his buttocks would not be visible, and how to be strong...The emphasis was on beauty...A beautiful boy is a good boy. Education is bound up with male love, an idea that is part of the pro-Spartan ideology of Athens...A youth who is inspired by his love of an older male will attempt to emulate him, the heart of educational experience. The older male in his desire of the beauty of the youth will do whatever he can improve it."

maenad and satyr

In Aristophanes's “ The Birds” , one older man says to another with disgust: "Well, this is a fine state of affairs, you demanded desperado! You meet my son just as he comes out of the gymnasium, all rise from the bath, and don't kiss him, you don't say a word to him, you don't hug him, you don't feel his balls! And you're supposed to be a friend of ours!"

Love

Simon May wrote in the Washington Post: “Only since the mid-19th century has romance been elevated above other types of love. For most ancient Greeks, for example, friendship was every bit as passionate and valuable as romantic-sexual love. Aristotle regarded friendship as a lifetime commitment to mutual welfare, in which two people become “second selves” to each other. [Source: Simon May, Washington Post, February 8, 2013. May, the author of “Love: A History,” is a visiting professor of philosophy at King’s College London]

“The idea of human love being unconditional is also a relatively modern invention. Until the 18th century, love had been seen, variously, as conditional on the other person’s beauty (Plato), her virtues (Aristotle), her goodness (Saint Augustine) or her moral authenticity (the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau). Even Saint Thomas Aquinas, perhaps the greatest of all Christian theologians, said we would have no reason to love God if He weren’t good.

Many of the great thinkers of love acknowledged its mortality. Aristotle said that love between two people should end if they are no longer alike in their virtues. Even Jesus seemed to suggest that God’s love for humanity isn’t necessarily eternal. After all, at the Last Judgment, the righteous will be rewarded with the Kingdom of God — with everlasting love — but those who did not act well in their lives will hear the heavenly judge say: “You that are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.” And Jesus adds: “These will go away into eternal punishment.”

Love in Ancient Greece

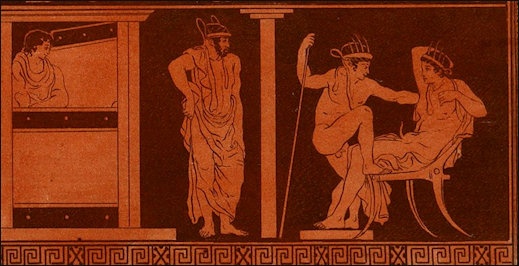

Courtship scene Some scholars claim that the idea of love began with the Greeks and the notion of romantic love began with chivalry in the Middle Ages. The ancient Greek poet Nimnerus wrote: "What is life, what is joy without golden Aphrodite?/ May I die when these things no longer move me?/ hidden love affairs, sweet nothings and bed."

According to one myth, Zeus originally created three sexes: men, women and hermaphrodites. The hermaphrodites had two heads, two set of arms and two sets of genitals. Alarmed by their power, he separated each one in half: some became lesbians, some became male homosexuals and some became heterosexuals. Each felt incomplete and spent his or her life trying to track his or her other half down.

Arisphanes expressed similar ideas. In an attempt define love he wrote: "Each of us when separated, having one side only, like a flat fish, is but the indenture of man, and he is always looking for his other half...And when one of them meets his other half, the actual half of himself, whether he be a lover of youth or of another sort, the pair are lost in amazement of love and friendship and intimacy, and will not be out of the other's sight, as I may say, even a moment...yet they could not explain what they desire in one another" other than "this meeting and melting into one another, this becoming one instead of two, was the very expression of an ancient need."

Plato espoused similar ideas. He viewed lovers as incomplete halves who could not find peace until they found each other. His ponderings in The “ Symposium” , a banquet staged in honor of Eros, are the oldest known attempt to systematically unravel the mysteries of love. In “ The Republic” , Plato wrote about marriage mainly as a means of reproduction while he wrote about the erotic loves in “ Symposium” in "blushingly romantic terms."

Ancient Greek Love Tablets

Kalliarista stele

from Rhodes A curse that focuses on erotic love found on a potsherd perhaps heated in a ritual read: “Burn, torch the soul of Allous, her female body, her limbs, until she leaves the household of Apollonius. Lay Allous low with fever, with unceasing sickness, lack of appetite, senselessness.”

The text of one Greek curse found rolled up in the mouth of a red-haired mummy found in Eshmunen in Ptolemaic Egypt read: “Aye, lord demain, attract, inflame, destroy, burn, cause her to swoon from love as she is being burnt, inflamed. Goad the tortured soul, the heart of Karosa...until she leaps forth and comes to Apalos...out of passion and love, in this very hour, immediately. Immediately, quickly, quickly...do not allow Karosa herself...to think of her [own] husband, her child, drink, food, but let her come melting for passion and love and intercourse, especially yeaning for the intercourse of Aapalos.”

One tablet addressed to a ghost goes: “Seize Euphemia and lead her to me Theon, loving me with mad desire, and bind her with unloosable shackles, strong ones of adamantine, for the love of me, Theon, and do not allow her to eat, drink, obtain sleep, jest or laugh but make her leap out...and leave behind her father. Mother, brothers, sisters, until she comes to me...Burn her limbs, live, female body, until she comes to me, and not disobeying me.”

Sex and Love Spells

John Opsopaus of hermetic.com wrote: “Most of the spells from the magical papyri here were discovered in Egypt the nineteenth century and brought together as part of the Anastasi Collection. It is quite likely that many of the papyri come from a single source, perhaps a tomb or temple library, and it is commonly supposed that they were collected by a Theban Magician. In any case, they are one of the best sources of Greco-Egyptian magic and religion.” [Source: John Opsopaus, Papyri Graecae Magicae hermetic.com |+|]

To be Able to Copulate a Lot: “Grind up fifty Tiny Pinecones with 2 ozs. of Sweet Wine and two Pepper Grains and drink it. [Papyri Graecae Magicae VII.184-5] |+|

To Get an Erection: When You Want Grind up a Pepper with some Honey and coat your Thing. [Papyri Graecae Magicae VII.186] |+|

Love Salve: Hawk's Dung; Salt, Reed, Bele Plant. Pound together. Anoint your Phallus with it and lie with the Woman. If it is dry, you should pound a little of it with Wine, anoint your Phallus with it, and lie with the Woman. Very Good. [Papyri Demoticae Magicae xiv.1155-62]

Love Spell: “Aphrodite's Name, which becomes known to No One quickly, is NEPHERIE'RI [i.e. Nfr-iry.t, “the beautiful eye”, an epithet for Aphrodite/Hathor] - this is the Name. If you wish to win a Woman who is beautiful, be Pure for 3 days, make an offering of Frankincense, and call this Name over it. You approach the Woman and say it seven times in your Soul as you gaze at her, and in this way it will succeed. But do this for 7 days. [Papyri Graecae Magicae IV.1265-74] |+|

Birth Control and Contraceptives in Ancient Greece

According to historians, demographic studies suggest the ancients attempted to limit family size. Greek historians wrote that urban families in the first and second centuries B.C. tried to have only one or two children. Between A.D. 1 and 500, it was estimated the population within the bounds of the Roman Empire declined from 32.8 million to 27.5 million (but there can be all sorts of reason for this excluding birth control).

silphion Birth control methods in ancient Greece included avoiding deep penetration when menstruation was "ending and abating" (the time Greeks thought a woman was most fertile); sneezing and drinking something cold after having sex; and wiping the cervix with a lock of fine wool or smearing it with salves and oils made from aged olive oil, honey, cedar resin, white lead and balsam tree oil. Before intercourse women tried applying a perceived spermicidal oil made from juniper trees or blocking their cervix with a block of wood. Women also ate dates and pomegranates to avoid pregnancy (modern studies have shown that the fertility of rats decreases when they ingest these foods).

Women in Greece and the Mediterranean were told that scooped out pomegranates halves could be used as cervical caps and sea sponges rinsed in acidic lemon juice could serve as contraceptives. The Greek physician Soranus wrote in the 2nd century A.D. : "the woman ought, in the moment during coitus when the man ejaculates his sperm, to hold her breath, draw her body back a little so the semen cannot penetrate into the uteri, then immediately get up and sit down with bent knees, and this position provoke sneezes."

Valuable Ancient Greek Contraceptive Plant

In the seventh century B.C., Greek colonists in Libya discovered a plant called “ silphion” , a member of the fennel family which also includes “ asafoetida” , one of the important flavorings in Worcester sauce. The pungent sap from silphion, the ancient Greeks found, helped relieve coughs and tasted good on food, but more importantly it proved to be an effective after-intercourse contraceptive. A substance from a similar plant called “ ferujol” has been shown in modern clinical studies to be 100 percent successful in preventing pregnancy in female rats up to three days after coitus. [Source: John Riddle, J. Worth Estes and Josiah Russell, Archaeology magazine, March/April 1994]

silphion symbol Known to the Greeks as silphion and to the Romans as silphium, the plant brought prosperity to the Greek city-state of Cyrene. Worth more than is weight on silver, it was described by Hippocrates, Diosorides and a play by Aristophanes.

Sixth century B.C. coins depicted women touching the silphion plant with one hand and pointing at their genitals with the other. The plant was so much in demand in ancient Greece it eventually became scarce, and attempts to grow it outside of the 125-mile-long mountainous region it grew in Libya failed. By the 5th century B.C., Aristophanes wrote in his play “ The Knights” , "Do you remember when a stalk of silphion sold so cheap?" By the third or forth century A.D., the contraceptive plant was extinct.

Abortions in Ancient Greece

Abortions were performed in ancient times, says North Carolina State history professor John Riddle, and discussions about featured many of the same arguments we hear today. The Greeks and Romans made a distinction between a fetus with features and one without features. The latter could be aborted without having to worry about legal or religious reprisals. Plato advocated population control in the ideal city state and Aristotle suggested that "if conception occurs in excess...have abortion induced before sense and life have begun in the embryo.”

The Stoics believed the human soul appeared when first exposed to cool air, and the potential for a soul existed at conception. Hippocrates warned physicians in his oath not to use one kind of abortive suppository, but the statement was misinterpreted as a blanket condemnation of all of abortion. John Chrystom, the Byzantine bishop of Constantinople compared abortion to murder in A.D. 390, but a few years earlier Bishop Gregory of Nyssa said the unformed embryo could not be considered a human being. [Riddle has written a book called “ Contraception and Abortion from the Ancient World to the Renaissance” ].

Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) On Rape and Adultery

The Law Code of Gortyn (450 B.C.) is the most complete surviving Greek Law code. According to the Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: “In Greek tradition, Crete was an early home of law. In the 19th Century, a law code from Gortyn on Crete was discovered, dealing fully with family relations and inheritance; less fully with tools, slightly with property outside of the household relations; slightly too, with contracts; but it contains no criminal law or procedure. This (still visible) inscription is the largest document of Greek law in existence (see above for its chance survival), but from other fragments we may infer that this inscription formed but a small fraction of a great code.” [Source:Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece, Fordham University]

“II. If one commit rape on a free man or woman, he shall pay 100 staters, and if on the son or daughter of an apetairos ten, and if a slave on a free man or woman, he shall pay double, and if a free man on a male or female serf five drachmas, and if a serf on a male or female serf, five staters. If one debauch a female house-slave by force he shall pay two staters, but if one already debauched, in the daytime, an obol, but if at night, two obols. If one tries to seduce a free woman, he shall pay ten staters, if a witness testify. . .

“III. If one be taken in adultery with a free woman in her father=s, brother=s, or husband=s house, he shall pay 100 staters, but if in another=s house, fifty; and with the wife of an apetairos, ten. But if a slave with a free woman, he shall pay double, but if a slave with a slave=s wife, five. . .

Sex Life of the Amazons

Joshua Rothman wrote in The New Yorker: The Greeks, of course, were fascinated by the Amazons’ sex lives. They came up with all sorts of lurid ideas—that they were single-breasted lesbians who killed their male children, or that they mated once a year with strangers to perpetuate an all-female society, or that an Amazon had to kill a man before she could lose her virginity. [Source: Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker, October 17, 2014]

“ The idea was that the Amazons had, in some sense, renounced their femininity. The reality of Amazon family life was different. There seems to have been great diversity in approaches to child rearing: archaeologists have found childrens’ skeletons interred with lone men, lone women, and couples. Some groups may have practiced “fosterage”: the exchange of children to cement alliances. The best accounts of “Amazon sex,” meanwhile, suggests that it “was robust, promiscuous. It took place outdoors, outside of marriage, in the summer season, with any man an Amazon cared to mate with.” (Among some groups, “the sign for sex in progress was a quiver hung outside a woman’s wagon.”)

“You can get a sense of the roundedness of the Amazon life by looking at Amazon names. Mayor worked with a linguist and vase expert to examine some of the words on vases depicting Amazons. Previously, they had been considered “nonsense words,” but they turned out to be “suitable names for male and female Scythian warriors in their own languages, translated for the first time after more than twenty-five hundred years.” These ancient Circassian names include Pkpupes, “worthy of armor”; Kepes, “hot flanks/eager sex”; Barkida, “princess”; and Khasa, “one who heads a council.”“

Herodotus on Coupling Between Scythian Youth and on the Amazons

Amazon

Joshua Rothman wrote in The New Yorker: “Nearby, there happened to be a settlement of Scythians. Most Scythians were nomadic, horse-riding people of the steppe. But these were Royal Scythians—wealthy traders who had settled in towns. To avoid being raided, the Royal Scythians sent out scouts, who discovered that the strange marauders were Amazons. The Scythians found this intriguing. They had planned to send soldiers to kill the marauders; instead, they assembled a party of nice young men. Life in town was luxurious, but it lacked a certain something: the Royal Scythian women mostly stayed indoors, doing chores and feeling bored. Maybe a few fearless, untamed Amazons could spice things up. The band of bachelors travelled out onto the steppe and found the horsewomen. They set up camp and hung around until, one afternoon, one of them encountered a single Amazon, walking alone. “Wordlessly he made advances and she responded,” Adrienne Mayor writes, in “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World.” “They made love in the grass. Afterward, the Amazon gestured to indicate that he should return the next day to the same spot—and to bring a friend. She made it clear that she would bring a friend too.” [Source: Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker, October 17, 2014]

“Soon, the Amazons and the Scythians consolidated their camps, and the young men extended a proposal: Why not come back and live with them? They had money, houses, and parents—surely settled life would be better than life on the steppe. The Amazons, incredulous, made a proposal in return: Why not leave town behind and live as they did: riding, raiding, and sleeping under the stars? The men packed their things. Herodotus reports that the Sarmatians, the people descended from that union, created a society characterized by gender equality, in which men and women led the same sort of life. It’s a story, Mayor points out, in which the “answer to the question of who will be dominated and tamed is no one.”“

Herodotus wrote in “Histories” Book 4, 110.1-117.1: “The youth went away and told his comrades; and the next day he came himself with another to the place, where he found the Amazon and another with her awaiting them. When the rest of the young men learned of this, they had intercourse with the rest of the Amazons. Presently they joined their camps and lived together, each man having for his wife the woman with whom he had had intercourse at first. Now the men could not learn the women's language, but the women mastered the speech of the men; and when they understood each other, the men said to the Amazons, “We have parents and possessions; therefore, let us no longer live as we do, but return to our people and be with them; and we will still have you, and no others, for our wives.” To this the women replied: “We could not live with your women; for we and they do not have the same customs. We shoot the bow and throw the javelin and ride, but have never learned women's work; and your women do none of the things of which we speak, but stay in their wagons and do women's work, and do not go out hunting or anywhere else.

“So we could never agree with them. If you want to keep us for wives and to have the name of fair men, go to your parents and let them give you the allotted share of their possessions, and after that let us go and live by ourselves.” The young men agreed and did this. So when they had been given the allotted share of possessions that fell to them, and returned to the Amazons, the women said to them: “We are worried and frightened how we are to live in this country after depriving you of your fathers and doing a lot of harm to your land. Since you propose to have us for wives, do this with us: come, let us leave this country and live across the Tanaïs river.” To this too the youths agreed; and crossing the Tanaïs, they went a three days' journey east from the river, and a three days' journey north from lake Maeetis; and when they came to the region in which they now live, they settled there.

“Ever since then the women of the Sauromatae have followed their ancient ways; they ride out hunting, with their men or without them; they go to war, and dress the same as the men. The language of the Sauromatae is Scythian, but not spoken in its ancient purity, since the Amazons never learned it correctly. In regard to marriage, it is the custom that no maiden weds until she has killed a man of the enemy; and some of them grow old and die unmarried, because they cannot fulfill the law.”

Prostitutes and Courtesansin Ancient Greece

Greek aristocrats had courtesans and all-make drinking parties often featured naked prostitutes. Marriages who often arranged and men sought satisfaction with courtesans or male lovers. Prostitutes at Ephesus advertised their services outside the doorway of the brothel with an inscription of a foot and a woman with a mohawk haircut.◂

The Greek women with the most power and freedom, surprisingly, were courtesans, known as “ hetaeras” . When they weren't working Grecian courtesans didn't have to maintain an image of virtue so they could do what they wanted, and they had money to do it with. [Source: "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum,||]

“On Wives and Hetairai (Prostitues),” “Demosthenes wrote (c. 350 B.C.): “We take a hetaira for our pleasure, a concubine for daily attention to our physical wants, a wife to give us legitimate children and a respected house.”

Strabo wrote in “Geographia,” (c. 20 A.D.) about Greece around 550 B.C: “And the temple of Aphrodite in Corinth was so rich that it owned more than a thousand temple slaves — prostitutes — whom both free men and women had dedicated to the goddess. And therefore it was also on account of these temple-prostitutes that the city was crowded with people and grew rich; for instance, the ship captains freely squandered their money, and hence the proverb, "Not for every man is the voyage to Corinth."”

Grecian consorts were similar to geisha girls. They entertained their patrons with poems, dancing and singing at drinking parties (called “symposiums” ). Sex was extra, in some cases a lot extra. Sometimes their prices were set according to how many sexual positions they had mastered. One courtesan who had mastered 12 positions charged the most for one called “ keles” (meaning "racehorse" in which the woman mounted the man from the top).

Famous Ancient Greek Courtesans

During the Golden Age of Greece perhaps the most powerful person after the Athenian leader Pericles was his consort Aspasia. Some historians claim she wrote many of his speeches and pulled strings behind the scene.

Lamia, a Greek courtesan, charged king Demetetrius of Macedonia 250 talents ($300,000) for her services. To pay off the expense the king instituted a tax on soap. The famous Athenian orator and statesman Demosthenes wanted the Sicilian-born Greek courtesan so bad he offered "1,000 drachmas for a single night." She took one look at him and upped the figure to 10,000 drachmas ($20,000), a figure he was still happy to pay.◂

Mnesarte was said to be the most beautiful prostitute in Greece during the 4th century B.C. Once when it looked as if she was going to be found guilty in a court of law for the crime of profanity, she ripped open her robe in front of the judge and was acquitted.◂

According to Hermippus of Smyrna the glamorous courtesan Phyrne was never seen naked but "at the great festival of the Eleuina and that of the Posidonoa.” There he wrote “in full sight of a crowd that had gathered from all over Greece, she removed her cloak and let loose her hair before stepping into the seas; and it was from her that Apelles painted his likeness of Aphrodite coming out of the sea." Other famous courtesans included Lais, Gnathaena and Naera.

Poems on Ancient Greek Prostitutes

Philemon wrote in “Hetairai” [Prostitutes] (c. 350 B.C.):

“But you did well for every man, O Solon:

For they do say you were the first to see

The justice of a public-spirited measure,

The savior of the State (and it is fit

For me to utter this avowal, Solon);

You, seeing that the State was full of men,

Young, and possessed of all the natural appetites,

And wandering in their lusts where they'd no business,

Bought women and in certain spots did place them,

Common to be and ready for all comers.

They naked stood: look well at them, my youth —

Do not deceive yourself; aren't you well off ?

You're ready, so are they: the door is open —

The price an obol: enter straight — there's

No nonsense here, no cheat or trickery;

But do just what you like, how you like.

You're off: wish her good-bye;

She's no more claim on you.”

[Source: Mitchell Carroll, Greek Women, (Philadelphia: Rittenhouse Press, 1908), pp. 96-103, 166-175, 210-212, 224, 250, 256-260]

Anaxilas wrote in Hetairai (c. 525 B.C.):

“The man whoe'er has loved a hetaira,

Will say that no more lawless, worthless race

Can anywhere be found: for what ferocious

Unsociable she-dragon, what Chimaira

Though it breathe fire from its mouth, what Charybdis,

What three-headed Skylla, dog o' the sea,

Or hydra, sphynx, or raging lioness,

Or viper, or winged harpy (greedy race),

Could go beyond those most accursed harlots?

There is no monster greater. They alone

Surpass all other evils put together.”

Eubulus wrote in “The Reproach of the Hetairai (c. 350 B.C.):

“By Zeus, we are not painted with vermilion,

Nor with dark mulberry juice, as you are often:

And then, if in the summer you go out,

Two rivulets of dark, discolored hue

Flow from your eyes, and sweat drops from your jaws

And makes a scarlet furrow down your neck,

And the light hair which wantons o'er your face

Seems gray, so thickly is it plastered o'er.”

Dancing Girls in Ancient Greece

maenad dancing with a satyr

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “Lipsius discourses on public prostitutes in the theatre. Telethusa and Quinctia were probably Gaditanian damsels who combined the professions of dancer and harlot. These dancing girls were called saltatrices. Ovid in his Amores, speaks of dancing women: 'One pleases by her gestures, and moves her arms to time, and moves her graceful sides with languishing art in the dance; to say nothing about myself, who am excited on every occasion, put Hippolytus there — he would become a Priapus.' Dancing was in general discouraged amongst the Romans. During the Republic and the earlier periods of the Empire women never appeared on the stage, but they frequently acted in the parties of the great. These dancing girls accompanied themselves with music (the chief instrument being the castanet) and sometimes with song. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

” In the Banquet of Xenophon reference is made to their agility and intelligence: “Immediately Ariadne entered the room, richly dressed in the habit of a bride, and placed herself in the elbow-chair ... Then a hoop being brought in with swords fixed all around it, their points upwards, and placed in the middle of the hall, the dancing-girl immediately leaped head foremost into it through the midst of the points, and then out again with a wonderful agility ... I see the dancing-girl entering at the other end of the hall, and she has brought her cymbals along with her ... At the same time the other girl took her flute; the one played and the other danced to admiration; the dancing-girl throwing up and catching again her cymbals, so as to answer exactly the cadency of the music, and that with a surprising dexterity.

“The costume of female acrobats was of the scantiest. In some designs the lower limbs of the figures are shown enveloped in thin drawers. From vase paintings we see that female acrobatic costume sometimes consisted solely of a decorated band swathed round the abdomen and upper part of the thighs, thus resembling in appearance the middle band adopted by modern acrobats. Juvenal speaks of the 'barbarian harlots with embroidered turbans', and the girls standing for hire at the Circus; and in Satire XI he says, 'You may perhaps expect that a Gaditanian singer will begin to tickle you with her musical choir, and the girls encouraged by applause sink to the ground with tremulous buttocks.' This amatory dancing with undulations of the loins and buttocks was called cordax; Plautus and Horace term a similar dance Iconici motus. Forberg, commenting on Juvenal, says, 'Do not miss, reader, the motive of this dance; with their buttocks wriggling the girls finally sank to the ground, reclining on their backs, ready for the amorous contest. Different from this was the Lacedaemonian dance bíbasis, when the girls in their leaps touched their buttocks with their heels. Aristophanes in Lysistrata writes — 'Naked I dance, and beat with my heels the buttocks.' And Pollux, 'As to the bíbasis, that was a Laconian dance. There were prizes competed for, not only amongst the young men, but also amongst the young girls; the essence of these dances was to jump and touch the buttocks with the heels. The jumps were counted and credited to the dancers. They rose to a thousand in the bíbasis.' Still worse was the kind of dance which was called eklaktisma, in which the feet had to touch the shoulders.”

Masturbation, Fellatio and Irrumation in Antiquity

Actor The Roman poet Martial (A.D. 40-104) in one of his epigrams wrote: 'Veneri servit amica manus' — 'Thy hand serves as the mistress of thy pleasure.' He also discussed Phrygian slaves masturbating themselves to overcome the amorous feelings which the sight of their master having connection with his wife provoked in them. Martial has many allusions. He tells us that Mercury taught the art to his son Pan, who was distracted by the loss of his mistress, Echo, and that Pan afterwards instructed the shepherds. Mirabeau mentions a curious practice which he declares to be prevalent amongst the Grecian women of modern times: that of using their feet to provoke the orgasm of their lovers. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Aristophanes, in the Wasps, touches on the subject, and one of the most charming of the shorter poems of Catullus contains an allusion: O Caelius, our Lesbia, Lesbia, that Lesbia whom Catullus more than himself and all his kin did love, now in the public streets and in alleys husks off the magnanimous descendants of Remus.

“The tertia poena (third punishment) referred to in Epigram 12 on page 42 is irrumation or coition with the mouth. The patient (fellator or sucker) provokes the orgasm by the manipulation of his (or her) lips and tongue on the agent's member. Galienus calls it lesbiari (Greek lesbiázein), as the Lesbian women were supposed to have been the introducers of this practice. Lampridius says: “That lecherous man, whose mouth even is defiled and dishonest.” Minutius Felix says:(They who lick men's middles, cleave to their inguina with lustful mouth). He refers to the ancient belief that the raven ejected the semen in coition from its beak into the female, a belief that Aristotle refuted.

“The Phoenicians used to redden their lips to imitate better the appearance of the vulva; on the other hand the Lesbians who were devoted to this practice whitened their lips as though with semen. The word 'husking' used by Glubit can be interpreted as describing irrumation or masturbation. Plutarch says that Chrysippus praised Diogenes for masturbating himself in the middle of the marketplace, and for saying to the bystanders: 'Would to Heaven that by rubbing my stomach in the same fashion, I could satisfy my hunger.'”

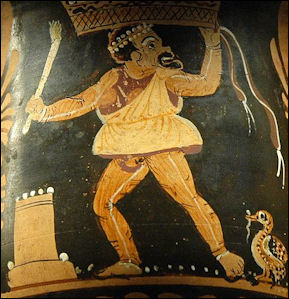

Bestiality and Greco-Roman Gods

Silenus The following passage from The Golden Ass by Apuleius (A.D. 125-170), a Carthage-based Latin-language prose writer and Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. “The mother of the Minotaur was Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos. Burning with desire for a snow-white bull, she got the artificer Daedalus to construct for her a wooden image of a cow, in which she placed herself in such a posture that her vagina was presented to the amorous attack of the bull, without fear of any hurt from the animal's hoofs or weight. The fruit of this embrace was the Minotaur — half bull, half man — slain by Theseus. According to Suetonius, Nero caused this spectacle to be enacted at the public shows, a woman being encased in a similar construction and covered by a bull. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

“The amatory adventures of the Roman gods under the outward semblance of animals cannot but be regarded with the suspicion that an undercurrent of truth runs through the fable, when the general laxity of morals of that age is taken into account. Jupiter enjoyed Europa under the form of a bull; Asterie, whom he afterwards changed into a quail, he ravished under the shape of an eagle; and Leda lent herself to his embraces whilst he was disguised as a swan. He changed himself into a speckled serpent to have connection with Deois (Proserpine). As a satyr (half man, half goat), he impregnated Antiope with twin offspring. He changed himself into fire, or, according to some, into an eagle, to seduce Aegina; under the semblance of a shower of gold he deceived Danaë; in the shape of her husband Amphitryon he begat Hercules on Alcmene; as a shepherd he lay with Mnemosyne; and as a cloud embraced Io, whom he afterwards changed into a cow. Neptune, transformed into a fierce bull, raped Canace; he changed Theophane into a sheep and himself into a ram, and begat on her the ram with the golden fleece. As a horse he had connection with the goddess Ceres, who bore to him the steed Arion. He lay with Medusa (who, according to some, was the mother of the horse Pegasus by him) under the form of a bird; and with Melantho, as a dolphin. As the river Enipeus he committed violence upon Iphimedeia, and by her was the father of the giants Otus and Ephialtes. Saturn begat the centaur (half man, half horse) Chiron on Phillyra whilst he assumed the appearance of a horse; Phoebus wore the wings of a hawk at one time, at another the skin of a lion. Liber deceived Erigone in a fictitious bunch of grapes, and many more examples could be added to the list.”

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: “According to Pliny, Semiramis prostituted herself to her horse; and Herodotus speaks of a goat having indecent and public communication with an Egyptian woman. Strabo and Plutarch both confirm this statement. The punishment of bestiality set out in Leviticus shows that the vice was practised by both sexes amongst the Jews. Pausanius mentions Aristodama, the mother of Aratus, as having had intercourse with a serpent, and the mother of the great Scipio was said to have conceived by a serpent. Such was the case also with Olympias, the mother of Alexander, who was taught by her that he was a God, and who in return deified her. Venette says that there is nothing more common in Egypt than that young women have intercourse with bucks. Plutarch mentions the case of a woman who submitted to a crocodile; and Sonnini also states that Egyptians were known to have connection with the female crocodile. Vergil refers to bestiality with goats. Plutarch quotes two examples of men having offspring, the one by a she-ass, the other by a mare. Antique monuments representing men copulating with goats (caprae) bear striking testimony to the historian's veracity; and the Chinese are notorious for their misuse of ducks and geese.”

Sex Positions of Cyrene and Elephantis

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Pindar's 9th Pythian ode, Cyrene or Kyrene (Ancient Greek:"sovereign queen") was the daughter of Hypseus, King of the Lapiths, although some myths state that her father was actually the river-god Peneus. She was a nymph who gave birth to the god Apollo, Aristaeus and Idmon while with Ares. She alsi identified as the mother of Diomedes of Thrace. Cyrene was a fierce huntress, called by Nonnus a "deer-chasing second Artemis, the girl lionkiller." [Source: Wikipedia +]

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: 'Cyrene was a celebrated whore, known under the name of Dodecamechanos, as she knew how to do the amorous work in twelve positions.' In “Frogs,” Aristophanes speaks of the dozen postures of Cyrene. In “Peace,” Aristophanes says, “So that you may, by lifting up her legs, Accomplish high in air the mysteries.” In “Birds,” he writes: “Of the girl you sent, I lifted first her feet, And entered her domain.” [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

“Elephantis was a Greek poetess who wrote on nine different sex positions in a famous sex manual that has been lost to time. According to Suidas, Astyanassa, the maid of Helen of Troy, was, the first writer on erotic postures, and Philaenis and Elephantis (both Greek maidens) followed up the subject. Aeschrion however ascribes the work attributed to Philaenis to Polycrates, the Athenian sophist, who, it is said, placed the name of Philaenis on his volume for the purpose of blasting her reputation. This subject occupied the pens of many Greek and Latin authors, amongst whom may be mentioned: Aedituus, an erotic poet noticed by Apuleius in his Apology: Annianus (in Ausonius); Anser, an erotic poet cited by Ovid; Aristides, the Milesian poet; Astyanassa, above mentioned; Bassus; Callistrate, a Lesbian poetess, noted for obscene verses.”

Elephantis (late 1st century B.C.) is credited with “setting out new modes of venery” ( pursuit of or indulgence in sexual pleasure). Due to the popularity of courtesans taking animal names in classical times, it is likely Elephantis is two or more persons of the same name. Elephantis was also a physician. Pliny references her performance as a midwife, and Galen notes her ability to cure baldness. She also wrote a manual about cosmetics and another about abortives. +

None of Elephantis works have survived, though they are referenced in other ancient texts. According to Suetonius, the Roman Emperor Tiberius took a complete set of her works with him when he retreated to his resort on Capri. One of the poems in the Priapeia refers to her books: "Lalage dedicates a votive offering to the God of the erect penis, bringing shameless pictures from the books of Elephantis, and begs him to try and imitate with her the variety of intercourse of the figures in the illustrations." And an epigram by the Roman poet Martial, which Smithers and Burton included in their collection of poems concerning Priapus, reads: "Such verses as neither the daughters of Didymus know, nor the debauched books of Elephantis, in which are set out new forms (“novae figura”) of lovemaking .") "Novae figurae" has been read as "novem figurae" (i.e., "nine forms" of lovemaking, rather than "new forms" of lovemaking), and so some commentators have inferred that she listed nine different sexual positions. +

Cunnilinges

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Cunnilinges — defined as causing “a woman to feel the venereal spasm by the play of the tongue on her clitoris and in her vagina” — was a taste much in vogue amongst the Greeks and Romans. Martial lashes it severely in several epigrams, that against Manneius being especially biting. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Catullus compares cunnilinges to bucks on account of their foetid breath; and Martial mocks at the paleness of Charinus's complexion, which he sarcastically ascribes to his indulgence in this respect. Maleager has a distich upon Phavorinus (Huschlaus, Anaketa Critica), and Ammianus (Brunck, Analecta) has written an epigram, both of which appear to be directed against the vice. Suetonius (Illustrious Grammarians) speaks of Remmius Palaemon, who was addicted to this habit, being publicly rebuked by a young man who in the throng could not contrive to avoid one of his kisses; and Aristophanes says of Ariphrades in Knights: ‘Whoever does not execrate that man, Shall never from the same bowl drink with us.’ According to Juvenal women were not addicted to exchanging this kind of caress with one another: 'Taedia does not lick Cluvia, nor Flora Catulla.'

“Many passages in the classics, both Greek and Roman, refer to the cunnilinges swallowing the menstrual and other secretions of women. Aristophanes frequently speaks of this. Ariphrades sods his tongue and stains his beard with disgusting moisture from the vulva. The same person imbibes the feminine secretion, 'And throwing himself on her he drank all her juice.' Galienus applies the appellation 'drinkers of menses' to cunnilinges; Juvenal speaks of Ravola's beard being all moist when rubbing against Rhodope's privities; and Seneca states that Mamercus Scaurus, the consul, 'swallowed the menses of his servant girls by the mouthful'. The same writer describes Natalis as 'that man with a tongue as malicious as it is impure, in whose mouth women eject their monthly Purgation.'

“In the Analecta of Brunck, Micarchus has an epigram against Demonax in which he says, 'Though living amongst us, you sleep in Carthage,' i.e. during the day he lives in Greece, but sleeps in Phoenicia, because he stains his mouth with the monthly flux, which is the colour of the purplish-red Phoenician dye. In Chorier's Aloisia Sigea, we find Gonsalvo de Cordova described as a great tongue-player (linguist). When Gonsalvo desired to apply his mouth to a woman's parts he used to say that he wanted to go to Liguria; and with a play upon words implying the idea of a humid vulva, that he was going to Phoenicia or to the Red Sea or to the Salt Lake--as to which expressions compare the salty sea of Alpheus and the salgamas of Ausonius and the 'mushrooms swimming in putrid brine' which Baeticus devours. As it was said of fellators (who sucked the male member) that they were Phoenicising because they followed the example set by the Phoenicians, so probably the same word was applied to cunnilinges from their swimming in a sea of Phoenician purple. Hesychius defines scylax (dog) as an erotic posture like that assumed by Phoenicians. The epithet excellently describes the action of a cunnilinge with regard to the posture assumed; dogs being notoriously addicted to licking a woman's parts. The reader who desires more information on the subject will find further details in Forberg, from whose pages I have drawn part of the material which constitutes this note.

“The word labda (a sucker) is variously derived from the Latin labia and do, to give the lips; and from the Greek letter lambda, which, is the first letter in the word leíchein or lesbiázein, the Lesbians being noted for this erotic vagary. Ausonius says, 'When he puts his tongue [in her coynte] it is a lambda'- that is the conjunction of the tongue with the woman's parts forms the shape of the Greek letter {lambda}. In an epigram he writes:

Lais, Eros and Itus, Chiron, Eros and Itus again,

If you write the names and take the initial letters

They will make a word, and that word you're doing, Eunus.

What that word is and means, decency lets me not tell.

(The initial letters of the six Greek names form the word leíchei, he licks)”

Sodomy in Antiquity

Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton wrote in the notes of “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus”: Paedico means to pedicate, to sodomise, to indulge in unnatural lewdness with a woman often in the sense of to abuse. In Martial’s Epigrams 10, 16 and 31 jesting allusion is made to the injury done to the buttocks of the catamite by the introduction of the 'twelve-inch pole' of Priapus. [Source: “Sportive Epigrams on Priapus” translation by Leonard C. Smithers and Sir Richard Burton, 1890, sacred-texts.com]

Orpheus is supposed to have introduced the vice of sodomy upon the earth. In Ovid's Metamorphoses: He also was the first adviser of the Thracian people to transfer their love to tender youths ...presumably in consequence of the death of Eurydice, his wife, and his unsuccessful attempt to bring her to earth again from the infernal regions. But he paid dearly for his contempt of women. The Thracian dames whilst celebrating their bacchanal rites tore him to pieces.

François Noël, however, states that Laius, father of Oedipus, was the first to make this vice known on earth. In imitation of Jupiter with Ganymede, he used Chrysippus, the son of Pelops, as a catamite; an example which speedily found many followers. Amongst famous sodomists of antiquity may be mentioned: Jupiter with Ganymede; Phoebus with Hyacinthus; Hercules with Hylas; Orestes with Pylades; Achilles with Patrodes, and also with Bryseis; Theseus with Pirithous; Pisistratus with Charmus; Demosthenes with Cnosion; Gracchus with Cornelia; Pompeius with Julia; Brutus with Portia; the Bithynian king Nicomedes with Caesar,[1] &c., &c. An account of famous sodomists in history is given in the privately printed volumes of 'Pisanus Fraxi', the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (1877), the Centuria Librorum Absconditorum (1879) and the Catena Librorum Tacendorum (1885),

Who Knocked the Phalluses Off Hermes?

Theater slave During the Peloponnesian War, an group of vandals went around Athens knocking the phalluses off Hermes - the steles with the head and phallus of the God Hermes which were often outside houses. This incident, which lead to suspicions of the Athenian general Alciabiades, provided Thucydides with a spring board to recount the story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, two homosexual lovers credited by the Athenians with overthrowing tyranny.

Thucydides wrote in “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book (ca. 431 B.C.): “There they found the Salaminia come from Athens for Alcibiades, with orders for him to sail home to answer the charges which the state brought against him, and for certain others of the soldiers who with him were accused of sacrilege in the matter of the mysteries and of the Hermae. For the Athenians, after the departure of the expedition, had continued as active as ever in investigating the facts of the mysteries and of the Hermae, and, instead of testing the informers, in their suspicious temper welcomed all indifferently, arresting and imprisoning the best citizens upon the evidence of rascals, and preferring to sift the matter to the bottom sooner than to let an accused person of good character pass unquestioned, owing to the rascality of the informer. The commons had heard how oppressive the tyranny of Pisistratus and his sons had become before it ended, and further that that had been put down at last, not by themselves and Harmodius, but by the Lacedaemonians, and so were always in fear and took everything suspiciously. [Source: Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” 6th. Book, ca. 431 B.C., translated by Richard Crawley]

In a review of Debra Hamel’s “The Mutilation of the Herms: Unpacking an Ancient Mystery,” Carolyn Swan of Brown University wrote in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review: “The ancient Greek herm—a semi-iconic statue, consisting of a rectangular stone pillar topped by the bearded head of Hermes and sporting an erect phallus (carved in relief or in-the-round)—is unquestionably an unusual sculptural type, and one that has never been treated in a particularly thorough or satisfactory manner. Likewise, the sudden and wide-scale mutilation of the Athenian herms in 415 B.C. is an event that remains puzzling despite the contemporary literary accounts that survive. Debra Hamel rightly draws attention to the ongoing obscurity of the event in this slim, self-published volume; she uses the event as a case study to illustrate both the principles and limitations of Classical scholarship to a non-Classicist and student audience. In seventeen short chapters—each chapter consisting of one to three pages of text, for a total of about 40 pages—Hamel presents the reader with an overview of the events of 415 B.C., identifies the men who were involved, and comments on the nature of their individual testimonies. [Source: Carolyn Swan, The Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2012.12.40]

“In her introductory chapter, Hamel gives a brief overview of the facts: one morning in the spring of 415 B.C. it was discovered that the herms dotting the urban landscape of Athens had been vandalized, which launched an investigation into impious acts and caused many Athenians to flee or be put to death. In the second chapter (“How Were the Herms Damaged?”), Hamel highlights the evidence for the manner in which the herms were actually vandalized. Although contemporary sources like Thucydides refer to the damage of faces (prosopa) specifically, Hamel speculates it is unlikely that the damage ended there. She points primarily to the references in Aristophanes’ 411 B.C. comedy Lysistrata (lines 1093-1094) that warns the ithyphallic characters in the play of the dangerous hermokopidai (“herm-choppers”), and thus Hamel suggests it would be reasonable to conclude that the phalloi of the statues did not escape the attention of the vandals.

“The third chapter (“The Sicilian Expedition”) identifies the Peloponnesian War and the Athenians’ planned naval attack on Sicily as the main social and historical context of the events under consideration. Hamel observes that the mutilation of the herms had a major impact on the Sicilian expedition—regardless of whether or not this outcome was the intention of the vandals. The Eleusinian Mysteries are introduced in Chapter Four (“The Mysteries”) as an integral part of the larger story. After the mutilated herms were discovered, a commission of inquiry was established to investigate the crime and rewards were offered for information about any sacrilegious acts (not just the desecration of the herms). Most importantly, Alcibiades—one of the three Athenian generals appointed to command the Sicilian expedition—was implicated in profanation of the Mysteries.

“The following four chapters make up a chronological discussion of the various witnesses who came forward and their testimonies about the mutilation of the herms and the profanation of the Mysteries. Chapter 5 (“Andromachus’ Testimony”) presents the first of these witnesses, a slave who implicated Alcibiades and ten other men in the profanation of the Mysteries, while Chapter 6 (“Alcibiades and the Departure of the Fleet”) describes Alcibiades’ reluctance to depart for Sicily before the charges brought against him were actually addressed in trial. Chapter 7 (“Teucer, Agariste, Lydus, and Leogoras”) outlines several testimonies that took place after Alcibiades’ departure, which included information about both the herms and the Mysteries. Chapter 8 (“Diocleides’ Story”) outlines an interesting but probably false eyewitness account of the herm mutilation; Chapter 9 suggests why the story of Diocleides was particularly believable, introducing to the reader the role of social clubs (hetaireiai) and drinking parties (symposia) in Athenian society.

“In the next three chapters, Hamel draws attention to the fact that the main source of evidence we have for the information presented during the inquiry comes from a speech given by Andocides ca. 400/399 B.C., when he himself was accused of profanation. Chapter 10 (“Andocides’ On the Mysteries”) introduces the circumstances of his trial and makes the point that Andocides was likely not an impartial reporter of the events of 415 B.C. Chapter 11 (“Andocides’ Story”) and Chapter 12 (“Was Andocides Guilty?”) are two of the slightly longer chapters of the book, describing in somewhat more detail the testimony of Andocides and its effect on the outcome of the inquiry, and considering whether he was lying about his own involvement in the impieties. Hamel wraps up her discussion of the evidence in Chapter 13 (“Case Closed”) by noting that Andocides’ confession largely ended the matter in the minds of the Athenians. She also acknowledges that most modern scholars accept the conclusion that members of a hetaireia were responsible for the mutilation of the herms, likely as a pledge of group trust (pistis). “

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018