ANCIENT GREEK TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE

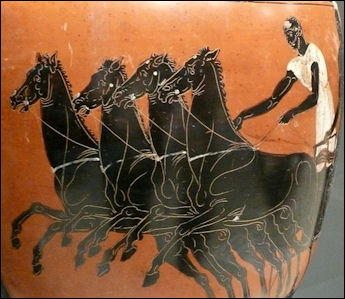

Leather sandal soles Egyptians, Assyrians and Greeks had chariots. The ancient Greeks seem to have used chariots mainly as transport and racing vehicles. One of the reasons for this was the rugged Greek countryside did not provide enough grazing land to feed a lot of horses, nor did it lend itself to chariot battles which need a lot of flat open space.

The Mycenaeans built roads graded for wagons and chariots. However ships were the primary vehicle for moving goods. Overland travel was difficult. Much fewer goods could be carried and the going was more difficult.

Ancient Greece had a postal system. The cost of sending a letter was around 2 talents and 300 drachmas, a considerable amount of money.

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

First Wheels and Wheeled Vehicles

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C. — the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Greek chariot Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — hows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

The wheel and axle were found near a wooden canoe. Both the wheel and the axle had been scorched, probably to protect them against pests. Slovenian experts surmise that the wheel they found belonged to a single-axle cart. The aperture for the axle on the wheel is square, which means the wheel and the axle rotated together and, considering the rough ground, the cart probably had only one axle. We can only guess what the cart itself was like. The Ljubljana marshes are a perfect place for old objects to be preserved. There have been many finds uncovered in this area. Apart from the wooden wheel, axle and canoe, there have been innumerable objects found which are up to 6,500 years old.

A wheel dated to 3000 B.C., was found near Lake Van in eastern Turkey. Wheels with simialr dates have been found in germany and Switzerland. One very old wheel was a wooden disc discovered at an archeological sight near Zurich. The wheel now can be seen in the Zurich museum.

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

First Domesticated Horses

horse on the Elgin Marbles The first domesticated horses appeared around 6000 to 5000 years ago. The first hard evidence of mounted riders dates to about 1350 B.C. Uncovering information about ancient horsemen however is difficult. They left behind no written records and relatively few other groups wrote about them. For the most part they were nomads who had few possession, and never stayed in one place for long, making it difficult for archeologists — who have traditionally excavated ancient cities and settlements of settled people — to dig up artifacts connected with them.

For similar reasons it is difficult to work out how different horsemen groups interacted and how individuals within the group behaved. What little is known about group interaction has been learned mostly from the work of linguists. Most of what is known about their behavior is based on observations of modern groups or a hand full of descriptions by ancient historians. . Based on these sources, scholars believe that early nomadic horsemen lived in small groups, often organized by clan or tribe, and generally avoided forming large groups. Small groups have more mobility and flexibility to move to new pastures and water sources. Large groups are much more unwieldy and more likely to generate feuds and other internal problems. On the steppe there generally was enough land for all so the only time horsemen needed to unite was to face a common threat.

The Eurasia steppe is the only place that horses survived after the last Ice Age. Domestication is believed to have occurred around 3000 B.C. when horses suddenly appeared in places where they hadn't been seen before like Turkey and Switzerland. It is difficult to pin down when domestication took place partly because the bones of wild horses and domesticated horses are virtually the same. [Source: William Speed Weed, Discover magazine, March 2002]

5th century BC figurine Horses are believed to have been domesticated from wild horses from Central Asia about 6,000 years ago. Ancient men viewed horses primarily as a source of meat and hunted them like other animals. One effective method of hunting horses was driving them over cliffs.

The first domesticated horses are believed to have been horses that were herded rather than hunted. Later they were used as beast of burdens, and later still they were ridden. Horse are believed to have first been ridden to keep track of domesticated animals that ranged over large expanses on the steppe. Some people have speculated that the first horsemen drank the blood of their animals as cattle-herding tribes in East Africa do today.

The first horseback riders and domesticated horses were originally believed to have come from Sredni Stog culture, a site in the steppe areas east of the Dnieper River and north of the Black Sea in what is now the Ukraine, dated between 4200 and 3500 B.C. Russian archeologists excavated Sredny Stog in the 1960s and found scraps of bone and horn that resembled the cheek pieces of bridles plus wear and tear on the teeth of an excavated horse that resembled the wear and tear caused by wearing a bit. Archeologist David Anthony of Hartwick College in New York examined horse teeth found at Sredni Stog sites and concluded the horse teeth dated to 400 B.C., and the site not the home of 6000-year-old riders.

Carts, Onangers and Horses

Bronze horse Animals pulling carts preceded mounted riders by as much as 2,000 years. A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur, dated to 2500 B.C., shows four onangers (donkey-like animals) pulling a cart for a king. The first animals used to pull sledges (carts without wheels) were probably oxen (bulls made more docile by castration). The first carts were probably sledges with logs rolled underneath them.

Over time onangers and donkeys — animals that often will not move even when furiously whipped — were later replaced by horses who are less stubborn, faster, and have a lower threshold for pain than a donkeys. In the second millennia B.C. horses were increasingly to pull weights on the Central Asian steppes. These horses were smaller and shaggier than modern horses, and much more difficult to control than oxen. Deep-furrowed plows also began to be utilized by farmers in the second millennia B.C. Muscular oxen proved to be much better suited for this kind of work than horses.

Herdsman at this time had learned to breed sheep, goats, and cattle, and it follows that they applied what they learned about breeding to horses. Through breeding, horses were made manageable enough to attach to carts with the mouth-fitted bit . By contrast donkeys were controlled by reins attached to nose rings and oxen were harnessed to yokes shaped around their shoulders.

First Horse-Pulled Chariots

Chariots preceded mounted riders by at least 1,000 years. Because oxen were better suited for pulling plows and heavy loads, horses were attached to lighter vehicles that evolved into chariots. Lightweight chariots, employing technology similar to that used to make racing bicycles light, could move quite fast. Ancient Egyptian chariots, pulled by a pair of horses and weighing only 17 pounds, could reach easily reach speeds of 20 miles-per-hour. A cart pulled by oxen, by contrast, rarely exceeded two miles-per-hour.

Chariots preceded mounted horses and saddles in part because the early domesticated horses were small and not strong enough to support men on their backs. The first chariots were probably used by shepherds to help them hunt wolves, leopards and bears that threatened their flocks and were alter adapted for warfare.

The important elements of a chariot were the wheels, chassis, draught pole and metal fittings. Advancement in metallurgy, woodworking, tanning and leatherworking, the uses of glues, bone and sinew all made the construction of chariots possible but the most important development of all was the improvement in physique of horse to pull such a vehicle.

Petroleum in the Ancient World

The first references to oil were made on cuneiform tablets in Babylonia in 2000 B.C. It was referred to as “ naptu” , which means "that which flares up." Naptu was used in construction, road building, waterproofing, skin ointments and cements. One cuneiform tablet from that era read: "If a certain place in the land “ naptu” oozes out, that country will walk in widowhood. If the water of a river bears...oil, want will seize on the peoples." Another states: "May donkey urine be your drink, “ naptu” your ointment."

Misfired clay lamps In the 5th century B.C. Herodotus described a famous spot in Persia where oil oozed from the ground. He wrote that a man with a wineskin "makes a dip with this, draws the liquid up, and then pours it over the receptacle, from there it passes into another, where it turns into three different shapes; the salt and the asphalt solidify while they collect on clay containers."

In ancient times oil came primarily from seepage. No one thought of drilling for in the ground until the 19th century. In the 1st century B.C., the Greek historian Diodorus wrote: "of all the marvels of Babylonia the most amazing is the mass of asphalt produced there...Uncountable numbers of people have drawn from it, as from some vast spring, yet the supply remains intact."

In the 1st century A.D., the Greek geographer Strabo wrote: "if naphtha is brought near a flame, it catches fire, and if you smear some on the body and come near a flame, the body will catch fire. It cannot be quenched with water — it just burns harder — unless a whole lot is used, but it can be smothered and quenched with mud, vinegar, alum or birdlime."

Romans burned petroleum in the their lamps instead of olive oil. The Byzantines used naptha for their Greek Fire weapons.

Ships in Ancient Greece

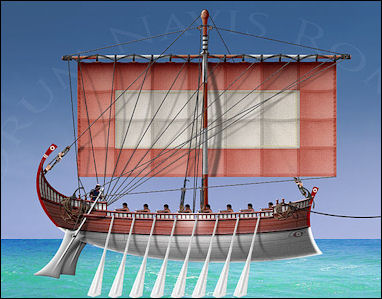

Greek ships were built of wood and had shelters to protect the crew from the fierce Mediterranean sun. Over the open sea they traveled using hand-woven square sails. Some were also outfit with oars. The planks were usually made of a soft wood like sealed pine placed across tennons of live oak and fastened with oak pegs and sealed with sap and resin. The keels and steering oars were made from a hard wood such as oak.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the largest human-power ship ever was a catamaran galley with 4,000 rowers built in Alexandria Egypt in 210 B.C. for Ptolemy II. The vessel was 420 feet long and had 8 men on each 57-foot oar.

building a ship Anchors were damaged or lost so often that ships often carried several of them. Rock was used as ballast. Early anchors were made of stone. Anchors from the 5th century B.C. had a lead core and wooden bod and looked like a Christian cross with a pick ax head, perpendicular to the cross, at the bottom. The weight of the lead help drive the pick-ax part of the anchor into the sea bed.

Many ships had decorative “eyes” placed on the bow of the ship to help guide the ship through the sea and avoid trouble. They were generally made from marble and were found on both merchant ships and war vessels. The custom remains alive today. One the roads of Turkey, truck drivers have “eyes” painted on their bumpers that serve a similar purpose.

Book: “ Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson

Navigation in Ancient Greece

Many ancient mariners navigated by looking at the coast. Most vessels were designed for hugging the coast. Navigation at night was done using stars such as the North Star as a reference point. One of the great problems with venturing southward along the African Coast was that once mariners passed below the equator, the North Star, the main reference point for celestial navigation, was no longer visible.

Hero's odometer, AD 1st century

Larry Freeman wrote in his Astronomy & Navigation Page:“ Sight Navigation: The earliest naval navigation consisted of following the coastline, watching for features on land that would mark their location (landmarks.) When these navigators lost sight of land, it was very likely they would could not find land again and would die. When fog came in, they could not sail close to land or they would run aground; nor could they sail too far from land or when the fog lifted they would be lost at sea. Also a storm could have the same effect. [Source: Larry Freeman's Astronomy & Navigation Page]

Sailing the latitude: By sighting on the North Star (Polaris), and measuring the angle to it from the horizon, navigators could tell how far in the north south direction (latitude) they were. If they knew the latitude of a location and whether the location was east or west of them, they could sail north or south to the latitude and then go east or west as required to reach the new location. This did require occasionally to see the North Star to determine their latitude and adjust their course accordingly.

Astrolabe: The astrolabe an instrument was invented by the Greeks to measure angles and was used to measure the angle to Polaris. It looked like a couple of school protractors fastened together at the center, so you would have a full circle instead of a half circle, and then putting a sighting rod pivoting at the center.

Astrolabes

Astrolabes — astronomical calculators used to solve problems relating to time and location based on the positions of the Sun and stars in the sky — were invented by the Greeks and improved by the Arabs. The only thing the Greek mariners needed to measure their latitudinal position was a sighting device that measured degrees above the horizon of either the sun or the north star. The north star was the easiest to measure because adjustments did not have to be made for the season like they did with the sun. The simple measuring device was made of two rods, hinged at one end. Held sideways, the bottom rod was leveled to the horizon and the upper one was pointed at the sun or star. The angle between the two rods yielded the angle of inclination of the sun or star, and with tables the latitude could be ascertained. More sophisticated astrolabes evolved from these devises.

AD 5th century Byzantine astrolabe

The Astrolabe enabled ship pilots to calculate latitude using the sun and stars. This in turn enabled the early explorers to venture out into the open sea without worrying about getting lost. Before the invention of the astrolabe most navigators stayed close to the shore so they could see where they were going. Longitude was more difficult to figure out. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

The astrolabe allowed mariners to use the sun and stars other than Polaris to determine latitude and direction and local time. Larry Freeman wrote in his Astronomy & Navigation Page: “The earth revolves on its axis nearly every 24 hours so the sun appears to revolve around the earth every 24 hours (on the average — our orbit is not circular). The sun is directly south (in the northern hemisphere) every noon (local time). The sun appears to move farther north as summer approaches and farther south as winter approaches because of the axis tilt. If you knew how far up in the sky the sun would be at noon and you measured how far the sun was up in the sky and how long away from noon (time before noon or after noon) you could compute your latitude. This analog computer was refined and used by the Arabic Moslems to do this calculation. It was called by the Europeans "astrolabe" (Greek meaning star taker). The Moslems needed to know the local time and their location so the would know when to pray and the direction to Mekka (Mecca) so they knew which direction to face. See Determine Directions with a Watch for an explanation how the time was determined. [Source: Larry Freeman's Astronomy & Navigation Page] “The astrolabe has a base that has measurements based on a close approximate to the latitude. Then it has a plate that slits on top of it that has a offset circle that represents the path of the sun through out the year. A rule is set on top of that and with measurements of the location of the sun to the offset circle, the local time and actual latitude and direction can be read off the underneath dial. They also added stars as little points on this plate so they could be used at night. The other side of this device provided the ability to measure the angles needed on the front side (the computer side). It could also be used to measure sine, cosine, and tangent of angles (cotangent of angles over 45 degrees). The first English technical manual, in 1391, was about the Astrolabe (Astrelabie) written by Geoffrey Chaucer, the same one that wrote "Canterbury Tales". The Astrolabe was considered to be the greatest of all scientific instruments.”

Ancient Greek Merchant Ships

cargo boat Merchant ships were generally sailing ships designed for sea travel or river travel. They had a few oars for maneuvering close to shore or in shallow water. They did not have large numbers of oars like fighting ships, which were designed to ram enemy ships.

Much of the cargo — usually grain, olive oil or wine — was carried amphorae (large clay jars) with two handles near the mouth that made it possible to pick them up and carry them. They generally were two to three feet tall and carried about seven gallons. Their shapes and markings were unique and these helped archaeologists date them and identify their place of origin.

A ship found off Cyprus, dated to 300 B.C., was 65 feet long and capable of carrying 2,000 to 3,000 amphorae. It was made of pine planks joined edge to edge with great skill.

The wreck of a merchant ship dated to 440-425 B.C., during the Greek Golden Age, was found in waters less than 100 meters deep off the west coast in Turkey about 40 kilometers south of Izmir. The ship was carefully excavated by archaeologists and its contents were brought to the surface and analyzed. The mid-size vessel was most likely used for coast-hugging, short-haul trips, most likely around the island of Chios. It mostly likely went down in a storm. The wooden hull had deteriorated but the shape of the ship could be determined by the contents that had been left behind. [Source: George Bass, National Geographic, March 2002]

Mostly what was discovered was amphorae. There were also hydria, kraters, drinking cups and pitchers made in nearby Chios, and they appear to have been cargo. Among the more interesting find were amphorae with cattle bones; oil lamps, one-handled cups; and the lead cores of wooden anchors.

See Rome, Trade, Archaeology

Large Merchant Ships

At the Antikythera shipwreck large hull planks were found Jacques Cousteau in the 1960s. Jo Marchant wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “At four inches thick, they rival those of 19th-century warships and are bigger than planks from the largest ships discovered from antiquity—including two 230-foot floating palaces sunk in Lake Nemi, Italy, built for the Roman emperor Caligula in the first century A.D. [Source: Jo Marchant, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015]

“If the ship is as large as the hull planks and anchors suggest, Foley speculates, it might be a grain carrier, either repurposed to carry a luxury cargo or transporting treasures along with what was most likely primarily wheat. These grain carriers were the biggest seagoing vessels in antiquity. Not one has been found, but ancient writers described how these oversized freighters traveled from Alexandria to Rome.

fighting ship “In the second century A.D., the Roman satirist Lucian described one such vessel, Isis, when it pulled in at Athens. Even larger was the Syracusia, reportedly built by Archimedes in the third century B.C. It carried grain, wool and pickled fish, and was equipped with flowerbeds, stables and a library. The cargo list of the maiden voyage, from Syracuse in Sicily to Alexandria, suggests it carried almost 2,000 tons. Finding one of these giants “has been one of the holy grails for archaeologists for generations,” Foley says. He can’t resist describing the Antikythera to journalists as “the Titanic of the ancient world.”“

Large Ancient Greek Ships

As time went the ships became larger and larger. Galleys rated as "fours," "fives," and "sixes" were introduced between 400 B.C. and 300 B.C. They were followed up by "16s," "20s" and "30s." The Emperor Ptolemy IV built a massive "40." The numbers refereed to the number pulling each triad of oars. Ships with more than three bank were built but ultimately they proved to be impractical.

Describing one of the largest boats, a 2nd century Greek wrote: "It was [420 feet] long, [58 feet] from gangway to plank and [72 feet] high to the prow ornament...It was double-prowed and double-sterned...During a trial run it took aboard over 4,000 oarsmen and 400 other crewmen, and on deck 2,850 marines."

In the late 1990s an English-Greek team built a 170-oar trireme at a cost of around $640,000. Held together with 20,000 tenons fastened with 40,000 oak pegs, it set sail with a an international crew of 132 men and 40 women. Describing, the team in action, Timothy Green wrote in Smithsonian, "the crew rowed together and sang together, getting up high spirits and up to seven knots.

Sea Travel and Routes in Ancient Greece

Xenophon described a "long day" journey by an oared vessel of 140 miles between Byzantium to Heracles on the southern shore of the Black Sea. The long day was believed to be 16 hours traveled at seven or eight knots an hour.

It was originally thought trade vessels hugged the coast within view of land and that Homer’s descriptions of open seas voyages and battling fierce storms was pure fantasy. Evidence for this was the fact that most shipwrecks were found near the shore.

But now it appears that ships regularly crossed the open Mediterranean out of site of land from Italy to Carthage in Northern Africa. These routes saved time and earned merchants sizable profits but some times ships was sunk in storms.

Evidence of this includes a Greek shipwreck, dated to 300 B.C., found in 10,000-foot-deep water in the middle of the eastern Mediterranean about 200 miles southwest of Cyprus. Surrounded by about 2,500 amphorae used to carry wine, the ship is the deepest ancient shipwreck and is believed to have been carrying wine from Rhodes to Alexandria. It was found by a team searching for a sunken Israeli submarine. The island of Rhodes controlled much of the sea trade in the eastern Mediterranean until the Roman era.

Fighting Ships, See Military

Greek colonies in Italy

Ancient Greece’s Huge Number of Ships and the Wood Needed to Build Them

Igor V.Bondyrev, of Georgian Academy of Sciences in Tbilisi, believes that one reason the colonization of the Black Sea region took place is that the Greek city states had exhausted their wood supplies to build huge numbers of ships to carry out military campaigns and trade, and needed new supplies of wood which the forests of the Black Sea region provided. [Source: Igor V. Bondyrev, Vakhushti Bagrationi Institute of Geography, Georgian Academy of Sciences, Tbilisi, Georgia, July 24, 2004]

Bondyrev wrote : According to research data on shipbuilding history [First, Patochka, 1977], it took from 2 to 4 thousand oak trees to construct a single ship and it oars. As about 100 to 800 trees grow on one hectare (ha) territory we may conclude that 25 to 40 ha of forest was felled for the construction of a single warship (32 ha on an average). It is quite clear that colonization of Pontus required much more ships and not only warships but freighters as well, which were 3- 4 times bigger.

Using the most rough calculations, about 10 to 12 thousand ships of different sizes took part in colonization, and thus 12000 x 32 ha =384,000 ha, or 3840 square kilometers, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. It should also be noted that the ships were seaworthy not more than 10 years. Therefore this figure is repeated every 10 year. For the 400 year period between the of 8th and 4th 4 centuries B.C., we get 384 000 ha x 400 = 153 600 000 ha, or 153,600, square kilometers of forest, an area equal to the size of England and Wales. “Such is the ecological value of one of the aspects of colonization of the Black Sea by the ancient Greeks.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, Boat pictures from the Terra Romana Project / Forum Navis Romana

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018