MYSTERY CULTS IN THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD

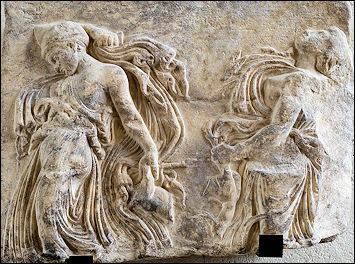

Dancing maenads There were hundreds of local gods and hundreds of cults, many devoted to specific gods. Many of the cults, were very secretive and had special initiation rituals with sacred tales, symbols, formulas and special rituals oriented towards specific gods. These are often described as mystery cults. Fertility cults and goddesses were often associated with the moon because its phases coincided the menstruation cycles of women and it was thought the moon had power over women.

Many of the cults, were very secretive and had special initiation rituals with sacred tales, symbols, formulas and special rituals oriented towards specific gods. These are often described as mystery cults. The word “mystery” come from the Greek word “mysterion,” which has a range of meanings, from the specific “Eleusinian ritual” to the more general “secret knowledge”. It often inferred something which one was initiated into.

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote:“Shrouded in secrecy, ancient mystery cults fascinate and capture the imagination. A pendant to the official cults of the Greeks and Romans, mystery cults served more personal, individualistic attitudes toward death and the afterlife. Most were based on sacred stories (hieroi logoi) that often involved the ritual reenactment of a death-rebirth myth of a particular divinity. In addition to the promise of a better afterlife, mystery cults fostered social bonds among the participants, called mystai. Initiation fees and other contributions were also expected. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Mystery cults continue to vex scholars because the surviving evidence is problematic, comprising a few written sources, mostly late in date, and often with questionable aims and biases. Modern reconstructions that view the mysteries as a cohesive religious phenomenon run the risk of oversimplification. Early twentieth-century scholarship, for instance, interpreted the ancient mysteries as a forerunner to Christian soteriological beliefs, thus challenging the latter's originality. The often interchangeable terminology found in the ancient texts, which encompasses variant ritual structures such as initiation and ecstasy (mysteria, mystes, telete, orgia), has encouraged the conception of unifying themes. Yet the wide variety and highly localized nature of these cults defy attempts at summary. One need only contrast the belief of the Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus that the purpose of the mysteries is purification and direct contact with the gods with the proclamation of the Christian apologist Clemens of Alexandria: "Here we see what mysteries are, in one word, murders and burials."” \^/

Mystery Cults generally had some kind of initiation. On initiations, Plato wrote that Socrates said: “I fancy that those men who established the mysteries were not unenlightened, but in reality had a hidden meaning when they said long ago that whoever goes uninitiated and unsanctified to the other world will lie in the mire, but he who arrives there initiated and purified will dwell with the gods. For as they say in the mysteries, 'the thyrsus-bearers are many, but the mystics few'; and these mystics are, I believe, those who have been true philosophers. And I in my life have, so far as I could, left nothing undone, and have striven in every way to make myself one of them. But whether I have striven aright and have met with success, I believe I shall know clearly, when I have arrived there, very soon, if it is God's will. [Source: Plato. “Plato in Twelve Volumes,” Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler; Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966]

Book: “Mystery Cults in the Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden (Thames and Hudson, 2010)

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece and Rome:

Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk;

Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ;

The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ;

Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history;

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Mysterious Things That Mystery Cult Members Did

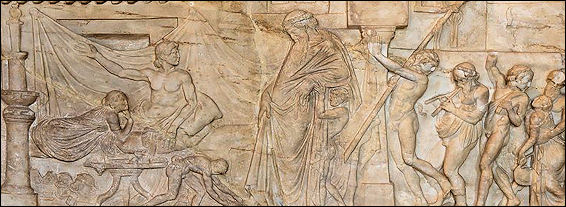

Dionysiac procession What went on in the mystery cult meetings and initiations is still largely a mystery. Members were expected to keep their “secret knowledge” secret. Altars for Hercules Roman initiation ceremonies depicted in a painting at the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, shows devotees reading liturgy, making offerings, symbolically suckling a goat, unveiling a mystic phallus, whipping themselves (symbolic of ritual death), dancing to resurrection and preparing for holy marriage.

Cambridge classics professor Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “Livy includes in his history of Rome a lurid tale of the cult of Bacchus, which stresses debauchery, murder and a clever trick with sulphurous torches, which stayed alight even when plunged into the waters of the Tiber. Early Christian writers found these initiatory cults a predictably easy target. Clement of Alexandria, for example, at the end of the second or beginning of the third century AD, tried to forge an etymological link between the ritual cry of the Bacchic worshippers (“euan, euoi”) and the Judaeo-Christian figure of Eve — helped by a reputed fondness of the Bacchists for snakes. Clement's idea was that they were actually worshipping the originator of human sin. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, June 2010 ==]

In a review of the book “Mystery Cults in Ancient World” by Hugh Bowden, Beard wrote: “For modern scholars, it has always been a frustrating task to discover the secret of these ancient mystery cults. What was it that the initiates of Dionysus or the “Great Mother” knew that the uninitiated did not? In his refreshing new survey, “Mystery Cults in Ancient World,” Hugh Bowden suggests that we have perhaps been worrying unnecessarily about that question. In fact, we don't have to imagine the ancients were so much better keepers of secrets than we are, for no secret knowledge, as such, was transmitted at all. To be sure, there was a whole range of objects involved in these cults that outsiders could not see, and words that they were not allowed to hear. (In the cult at Eleusis, from descriptions of the public procession to the sanctuary, we can judge that the cult objects were small — at least small enough comfortably to be carried in containers by the priestesses.) But that is quite different from thinking that some particular piece of secret doctrine was revealed to the faithful at their initiation.”

How true some of the descriptions of cult activities were is a matter of debate. Beard wrote that Bowden “takes many scholars to task (myself included) for assuming that the cult of the Great Mother in Rome, based on the Palatine Hill, just next to the Roman imperial palace, was served by ecstatic eunuch priests who castrated themselves with a piece of flint. Some of us had already been a little more circumspect about this than Bowden allows: you only have to read accounts of pre-modern full castration (for the Great Mother was supposed to demand the removal of both penis and testicles) to recognize that few priests could have survived any such procedure. But he shows that, feasible or not, the practice is anyway much less clearly attested in Roman literature than we like to think. “More often than not, in fact, the details of these cults may not be quite as they seem." Bowden “cites an intriguing second-century AD inscription from just outside Rome, listing the members of a Bacchic troupe (or thiasos), under a priestess called Agripinilla. It is anyone's guess whether we see here a group of respectable Roman men and women really imitating the mad Bacchants of Euripides’ play, and taking to the mountains in religious fervour — or whether this was the ancient equivalent of modern morris dancing (that is to say the Roman equivalent group of bank managers on their days off pretending to be lusty medieval rustics). My hunch, as Bowden almost suggests, is the latter.

“This overlap between civic and initiatory religion comes out particularly vividly in a series of inscriptions commemorating leading pagan aristocrats of the late Roman Empire, which proudly list all their religious offices — initiation into mystery cults next to official state priesthoods. These were men who boasted of holding the traditional offices of augur or pontifex, as well as of being initiated into the cult of Mithras or Egyptian Isis. Bowden rightly focuses on these at the end of his book and argues against a common view that they reflect a new form of aggressive pagan religiosity, developed in response to the rise of Christianity, or that they are part of a pagan “revival” in a Christian context. Much more likely they show — albeit under the magnifying glass of late imperial Rome (where everything appears larger than life) — just how closely different forms and styles of cult, “mystery” or not, had always gone hand in hand. However secretive they might have been about what went on in their ceremonies, however uncertain or elusive the “message” of the cults might have been amid all that sound and light — initiation in a variety of different cults was something that these late antique aristocrats were happy to parade.

bacchanal

Analysis of Mystery Cults in Ancient Greece

Beard wrote, “Bowden would prefer to see the religious culture of the mysteries in “imagistic” terms. Drawing — perhaps a little over-enthusiastically — on recent work on the anthropology of prehistoric religions, he contrasts imagistic with doctrinal forms of religious experience. The latter are best seen in the institutionalized, regular patterns of (relatively low-key) worship, associated with modern mainstream Christianity. The former rely on the kind of striking, occasional, intense, episodic moments of religious change that are associated with ancient mystery and initiatory cults: impressive and mind-blowing maybe, but not defined by a doctrinal message (hence all that stuff about sound and light).

For Bowden, what these initiatory religions offer is a face-to-face vision of the divine. One of the big issues of Greek and Roman culture in general is exactly how far the gods are, safely, visible to mortals. The cautionary mythological tale here is that of Semele, who (as brilliantly refigured in Handel’s opera) demands to look at her lover, Jupiter, only to be destroyed by that vision of godhead. In standard ancient ritual practice, there were all kinds of ways in which the worshipper’s direct vision of the gods was avoided (through representation in statues, for example). Bowden shows convincingly that the mysteries broke through this veil, and offered a direct vision of the god — and, unlike Semele’s experience, one that did not kill the worshipper. As Lucius, the initiand in the cult of Isis in Apuleius” novel The Golden Ass, observes: “I approached the gods below and the gods above face-to-face, and worshipped them from nearby”.

But it is also the case that some of the concerns of the initiatory religions overlap strikingly with those of civic cult. Bowden rightly lays stress on all kinds of problematic issues of naming, and on the uncertainty of divine identity within mystery cults. Some mystery gods are nameless, some are addressed under a variety of alternative titles. Some inscribed texts hedge their bets: “Great Gods of Samothrace”, or “Dioscuri”, or “Kabeiroi”? Uncertainty and ambivalence, in Bowden’s view, were part of the essence of the mysteries. But so also were they part of the essence of civic cults, where those who wanted to play safe in addressing a god always hedged their bets: “whether you are god or goddess” was a standard Roman formula of prayer, just to make sure that there had been no mistake about the sex of the deity.

Likewise the question of incomprehensibility. As Bowden explains, the Greek mysteries of the island of Samothrace “included someone reciting incomprehensible words” — another index of the intellectual puzzlement at the heart of such mystery cults. But, although Bowden does not mention it, there is plenty of incomprehensibility in ancient civic, official cults too: in the first century AD, when the priests known as the “salii” danced through the streets of Rome twice a year and sang their special hymn, no one (not even the priests themselves) had the foggiest clue what the hymn meant. Perhaps in the early periods of Rome’s history, the participants had understood; or more likely it had always been mumbo-jumbo. All ancient religion celebrates its own incomprehensibility, as part of its mystique.

Pythagoras Emerging from the Underworld by Salvator Rosa

History of Mystery Cults

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Most mysteries started as family or clan cults and were later taken over by the city-state, the polis, as in the case of the Theban Kabeiria. Kabeiros and his son Pais, collectively known as Kabeiroi, were patrons of herdsmen worshipped in Boeotia and Lemnos. In the absence of written sources, valuable information for their enigmatic cult comes primarily from excavations at their sanctuary in Thebes. The architectural remains of the Theban Kabeirion reveal a concern with controlling access and directing foot traffic. Most probably there were preliminary sacrifices, a procession, and, at least in Roman times, initiation in two stages (epopteia and myesis) performed inside the anaktoron, the main hall of the sanctuary. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Numerous votive figurines of bulls, often inscribed, have been retrieved from the site together with a very distinctive type of locally manufactured pottery, the so-called kabeirion ware. Beginning around 450 B.C., these are almost exclusively drinking cups, either black-glazed or decorated with black-figure vegetation motifs, and less often, Pygmy-like grotesque figures. Understood in the context of the symposium, these vases were probably custom made according to the specifications of the cult participants. \^/

“Known among the Greeks as Kybele, or Great Mother of the Gods (Matar Kubileya, mother of mountains in Phrygia, or Kubaba in neo-Hittite), originated in Anatolia, where there was a long-standing tradition of worshipping mother figures. It was imagined that Kybele resided on inaccessible mountain tops where she ruled over wild animals. The goddess is represented wearing a long belted dress, a polos headdress, and a veil. She is seated on a throne flanked by two lions and holds a tympanon, a circular drum resembling a tambourine, and a libation bowl . Ritual purity was a prerequisite of initiation into the ecstatic cult of the Mother. Her priests, the Korybantes, and followers worshipped her with wild, loud music produced by cymbals and frenzied dancing, which, like the revels in honor of Dionysos, carried the participants despite and beyond themselves. By the third century B.C., the Mother became important at Ilium and Pergamon and hence eventually Rome, where she was worshipped as Magna Mater. \^/

“In 395 A.D., the sanctuary of Eleusis was destroyed by the Goths and was never rebuilt. The Emperor Theodosius with a series of decrees forbade pagan worship and ordered the destruction of temples and altars. By the fifth century, the mysteries were extinct.”

Dionysus Cult

Because his half-breed status made his position at Olympus tenuous, Dionysus did everything he could to make his mortal brethren happy. He gave them rain, male semen, the sap of plants and "the lubricant and stimulant of dance and song" — wine.

In return the Greeks held winter-time festivals in which large phalluses was erected and displayed, and competitions were held to see which Greek could chug his or her jug of wine the quickest. Processions with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and nymphs were staged, and at the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed. [Source: "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin,μ]

The text believed to be from funeral of an Dionysus cult initiate read: “I am a son of Earth and Starry Sky; but I am desiccated with thirst and am perishing, therefore give me quickly cool water flowing from the lake of recollection.” The “long, cared way which also other...Dionysus followers gloriously walk” is “the holy meadow, for which the initiate is not liable for penalty” or “shall be a god instead of a mortal.”

Dionysos

During Thesmophoria, an annual Athenian event to honor Demeter and Persephone, women and men who required to abstain from sex and fast for three days. Women erected bowers made of branches and sat there during their fast. On the third day they carried serpent-shaped images thought to have magical powers and entered caves to claim decayed bodied of piglets left the previous years. Pigs were sacred animals to Demeter. The piglet remains were laid on an Thesmphoria altar with offerings, launching a party with feasting, dancing and praying. This rite also featured little girls dressed up as bears.

Wild Dionysus Festivals

To pay their respect to Dionysus, the citizens of Athens, and other city-states, held a winter-time festival in which a large phallus was erected and displayed. After competitions were held to see who could empty their jug of wine the quickest, a procession from the sea to the city was held with flute players, garland bearers and honored citizens dressed as satyrs and maenads (nymphs), which were often paired together. At the end of the procession a bull was sacrificed symbolizing the fertility god's marriage to the queen of the city.μ

The word “maenad” is derived from the same root that gave us the words “manic” and “madness”. Maenads were subjects of numerous vase paintings. Like Dionysus himself they often depicted with a crown of iv and fawn skins draped over one shoulder. To express the speed and wildness of their movement the figures in the vase images had flying tresses and cocked back head. Their limbs were often in awkward positions, suggesting drunkenness.

The main purveyors of the Dionysus fertility cult "These drunken devotees of Dionysus," wrote Boorstin, "filled with their god, felt no pain or fatigue, for they possessed the powers of the god himself. And they enjoyed one another to the rhythm of drum and pipe. At the climax of their mad dances the maenads, with their bare hands would tear apart some little animal that they had nourished at their breast. Then, as Euripides observed, they would enjoy 'the banquet of raw flesh.' On some occasions, it was said, they tore apart a tender child as if it were a fawn'"μ

One time the maenads got so involved in what they were doing they had to be rescued from a snow storm in which they were found dancing in clothes frozen solid. On another occasion a government official that forbade the worship of Dionysus was bewitched into dressing up like a maenad and enticed into one of their orgies. When the maenads discovered him, he was torn to pieces until only a severed head remained.μ It is not totally clear whether the maenad dances were based purely on mythology and were acted out by festival goers or whether there were really episodes of mass hysteria, triggered perhaps by disease and pent up frustration by women living in a male-dominate society. On at least one occasion these dances were banned and an effort was made to chancel the energy into something else such as poetry reading contests.

Eleusinian Mysteries

Eleusinian hydria Antikensam

Mary Beard wrote in the Times of London, “The ancient Greeks and Romans must have been very good at keeping secrets. Or so our lack of information on the famous “Eleusinian Mysteries” (celebrated in an impressive sanctuary just a few miles outside Athens) would suggest — not to mention our lack of information on all the other, similar, initiatory religions found throughout the ancient world, from the ecstatic cult of Dionysus featured in Euripides’ Bacchae to the worship of the god Mithras by the Roman squaddies on Hadrian’s wall. There must have been literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of initiates, across the millennium of Classical history. And at Eleusis they included some of the most prominent (and garrulous) writers, thinkers and politicians of antiquity: Socrates and Plato, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius, and many more. These cults are often set apart, by modern writers, from the calmer, less participatory, less emotional traditions of Graeco-Roman state religion. But we have no explicit ancient account of what the secret mysteries of any cult actually were, what happened at initiation or what exactly was revealed to the initiates. So far as we can now tell, there was hardly a leaky vessel among them; or, at any rate, whatever the gossip on the ancient street, there was no one who risked committing the religious secrets to writing and so sharing them with posterity. [Source: Mary Beard, Times of London, June 2010]

It is true that on one notorious occasion, in the middle of the Peloponnesian War just before the disastrous expedition sailed to Sicily, a group of elite young Athenians were said to have parodied the Eleusinian Mysteries at private parties, and so “revealed the secret things to the uninitiated”. The jape (assuming it was no more than that) had a deathly serious end. Prosecuted for the offence, the men were found guilty and — those that had not escaped into exile first — were executed. But we hear of nothing of that kind ever again. The attitude of Pausanias in his second-century ad Guide to Greece is far more typical. Whenever he comes to describe a sanctuary of a secret cult of this type, he makes it very clear that he cannot give the game away. At Eleusis he even claims to have been warned in a dream not to divulge any of “the things within the wall of the sanctuary” — because “the uninitiated [that is, many of his readers] are not allowed to learn about what they cannot take part in”.

In the absence of any explicit eyewitness (or even second-hand) accounts, we have to rely on various kinds of indirect evidence. There are some general descriptions of initiation by ancient writers, which often dwell on strange sounds and bright lights, or the clash of light and dark. There are some notable works of literature which may engage with the theology of these cults: the so-called “Homeric Hymn to Demeter”, which tells the story of Demeter’s grief after the rape of her daughter Persephone by Hades, is often thought to reflect the myth underlying the rituals at Eleusis. There are also a number of speculative, and probably almost entirely imaginary, accounts written by ancient critics of the cults.

Roman Mystery Cults

Basket of snakes on a Roman sarcophagus

Mystery cults dedicated to Bachus were popular in the Roman Empire. Cults for Isis and Osiris and Mithras were popular with traders and soldiers. Initiates to cults honoring Cybele in Asia Minor were baptized in bull blood, which some thought ensured eternal life. Once accepted into the cult devotees were expected to castrate themselves as offering of their fertility in exchange for the fertility of the world. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Scholars have long argued that the idea of mystery cults was introduced to Rome from the East. Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “The weakening of the old stock and the constantly increasing number of Orientals in the West, along with the campaigns of the armies in the East naturally encouraged the introduction of eastern cults and the spread of their influence. The cult of the Magna Mater found a reviving interest among the people from her part of the world. The mystery religions gained strength, with their rites of purification and assurance of happiness after death. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Among them the worship of Isis had come from Alexandria with the Egyptians and spread among the lower classes. Mithraism came in from the eastern campaigns with the captives, and later with the troops that had served or had been enlisted in the East. It established itself in Rome and in other cities and followed the army from camp to camp. There were many Jews in Rome, and their religion made some progress. Christianity appeared at Rome first among the lower classes, particularly the Orientals, and finally made its way upward.” |+|

Personal Piety, Mystery Cult Membership and Talisman

On personal piety in Rome, Lucius Apuleius (c.123-c.170 A.D.) wrote in Apologia 55-6: “ I might discourse at greater length on the nature and importance of such accusations, on the wide range for slander that this path opens for Aemilianus, on the floods of perspiration that this one poor handkerchief, contrary to its natural duty, will cause his innocent victims! But I will follow the course I have already pursued. I will acknowledge what there is no necessity for me to acknowledge, and will answer Aemilianus' questions. You ask, Aemilianus, what I had in that handkerchief. Although I might deny that I had deposited any handkerchief of mine in Pontianus' library, or even admitting that it was true enough that I did so deposit it, I might still deny that there was anything wrapped up in it. If I should take this line, you have no evidence or argument whereby to refute me, for there is no one who has ever handled it, and only one freedman, according to your own assertion, who has ever seen it. Still, as far as I am concerned I will admit the cloth to have been full to bursting. Imagine yourself, please, to be on the brink of a great discovery, like the comrades of Ulysses who thought they had found a treasure when they stole the bag that contained all the winds. Would you like me to tell you what I had wrapped up in a handkerchief and entrusted to the care of Pontianus' household gods? You shall have your will. [Source: “Apologia and Florida Of Apuleius of Madaura, translated by H.E.. Butler Fellow of New College, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1909, gutenberg.org]

gold Roman amulet

“I have been initiated into various of the Greek mysteries, and preserve with the utmost care certain emblems and mementoes of my initiation with which the priests presented me. There is nothing abnormal or unheard of in this. Those of you here present who have been initiated into the mysteries of father Liber alone, know what you keep hidden at home, safe from all profane touch and the object of your silent veneration. But I, as I have said, moved by my religious fervour and my desire to know the truth, have learned mysteries of many a kind, rites in great number, and diverse ceremonies. This is no invention on the spur of the moment; nearly three years since, in a public discourse on the greatness of Aesculapius delivered by me during the first days of my residence at Oea, I made the same boast and recounted the number of the mysteries I knew. That discourse was thronged, has been read far and wide, is in all men's hands, and has won the affections of the pious inhabitants of Oea not so much through any eloquence of mine as because it treats of Aesculapius. Will any one, who chances to remember it, repeat the beginning of that particular passage in my discourse? You hear, Maximus, how many voices supply the words. I will order this same passage to be read aloud, since by the courteous expression of your face you show that you will not be displeased to hear it. (The passage is read aloud.)

“Can any one, who has the least remembrance of the nature of religious rites, be surprised that one who has been initiated into so many holy mysteries should preserve at home certain talismans associated with these ceremonies, and should wrap them in a linen cloth, the purest of coverings for holy things? For wool, produced by the most stolid of creatures and stripped from the sheep's back, the followers of Orpheus and Pythagoras are for that very reason forbidden to wear as being unholy and unclean. But flax, the purest of all growths and among the best of all the fruits of the earth, is used by the holy priests of Egypt, not only for clothing and raiment, but as a veil for sacred things. And yet I know that some persons, among them that fellow Aemilianus, think it a good jest to mock at things divine. For I learn from certain men of Oea who know him, that to this day he has never prayed to any god or frequented any temple, while if he chances to pass any shrine, he regards it as a crime to raise his hand to his lips in token of reverence. He has never given firstfruits of crops or vines or flocks to any of the gods of the farmer, who feed him and clothe him; his farm holds no shrine, no holy place, nor grove. But why do I speak of groves or shrines? Those who have been on his property say they never saw there one stone where offering of oil has been made, one bough where wreaths have been hung. As a result, two nicknames have been given him: he is called Charon, as I have said, on account of his truculence of spirit and of countenance, but he is also—and this is the name he prefers—called Mezentius, because he despises the gods. I therefore find it the easier to understand that he should regard my list of initiations in the light of a jest. It is even possible that, thanks to his rejection of things divine, he may be unable to induce himself to believe that it is true that I guard so reverently so many emblems and relics of mysterious rites. I care not a straw what Mezentius may think of me; but to others I make this announcement clearly and unshrinkingly. If any of you that are here present had any part with me in these same solemn ceremonies, give a sign and you shall hear what it is I keep thus. For no thought of personal safety shall induce me to reveal to the uninitiated the secrets that I have received and sworn to conceal.”

Magna Mater (Cybele) Cults

Magna Mater (Cybele)

Magna Mater ("Great Mother") was the Roman version of Cybele, an Anatolian mother goddess that may date back to 10,0000-year-old Çatalhöyük, the world’s oldest town, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations. She is Phrygia's only known goddess, and was probably its state deity. Her Phrygian cult was adopted and adapted by Greek colonists of Asia Minor and spread to mainland Greece and its more distant western colonies around the 6th century B.C.. Some scholars say the cult of Cybele was brought to Rome in 205 or 204 B.C.. The Roman state adopted and developed a particular form of her cult after the Sibylline oracle recommended her conscription as a key religious ally in Rome's second war against Carthage. Roman mythographers reinvented her as a Trojan goddess, and thus an ancestral goddess of the Roman people by way of the Trojan prince Aeneas. With Rome's eventual hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Romanized forms of Cybele's cults spread throughout the Roman Empire. The meaning and morality of her cults and priesthoods were topics of debate and dispute in Greek and Roman literature, and remain so in modern scholarship. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 204 B.C., during the Second Punic War, the Romans consulted the Sibylline Oracles, which declared that the foreign invader would be driven from Italy only if the Idaean Mother (Cybele) from Anatolia were brought to Rome. The Roman political elite, in a carefully orchestrated effort to unify the citizenry, arranged for Cybele to come inside the pomerium (a religious boundary-wall surrounding a city), built her a temple on the Palatine Hill, and initiated games in honor of the Great Mother, an official political and social recognition that restored the pax deorum. [Source: Claudia Moser, Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2007, metmuseum.org \^/]

“After Cybele and the foreign ways of her exotic priesthood were introduced to Rome, she became a popular goddess in Roman towns and villages in Italy. But the enthusiasm that accompanied the establishment of her cult was soon followed by suspicion and legal prohibitions. The eunuch priests (galli) that attended Cybele's cult were confined in the sanctuary; Roman men were forbidden to castrate themselves in imitation of the galli, and only once a year were these eunuchs, dressed in exotic, colorful garb, allowed to dance through the streets of Rome in jubilant celebration. Nevertheless, the popularity of the goddess persisted, especially in the Imperial period, when the ruling family, eager to emphasize its Trojan ancestry, associated itself with and publicly worshipped Cybele, a goddess whose epithet, Mater Idaea, designated her as Trojan and whose cult was deeply connected with Troy and its origins.” \^/

Livy on Magna Mater Cults

Magna Mater box

Livy wrote in “History of Rome” (A.D. c. 10): “About this time the citizens were much exercised by a religious question which had lately come up. Owing to the unusual number of showers of stones which had fallen during the year, an inspection had been made of the Sibylline Books, and some oracular verses had been discovered which announced that whenever a foreign foe should carry war into Italy he could be driven out and conquered if the Mater Magna were brought from Pessinos [in Phrygia] to Rome. The discovery of this prediction produced all the greater impression on the senators because the deputation who had taken the gift to Delphi reported on their return that when they sacrificed to the Pythian Apollo the indications presented by the victims were entirely favorable, and further, that the response of the oracle was to the effect that a far grander victory was awaiting Rome than the one from whose spoils they had brought the gift to Delphi. In order, therefore, to secure all the sooner the victory which the Fates, the omens, and the oracles alike foreshadowed, they began to think out the best way of transporting the goddess to Rome. [Source: Livy, “The History of Rome,” by Titus Livius, translated by D. Spillan and Cyrus Edmonds, (New York: G. Bell & Sons, 1892); The Bible (Douai-Rheims Version), (Baltimore: John Murphy Co., 1914)]

“In this state of excitement men's minds were filled with superstition and the ready credence given to announcement of portents increased their number. Two suns were said to have been seen; there were intervals of daylight during the night; a meteor was seen to shoot from east to west; a gate at Tarracina and at Anagnia a gate and several portions of the wall were struck by lightning; in the temple of Juno Sospita at Lanuvium a crash followed by a dreadful roar was heard. To expiate these portents special intercessions were offered for a whole day, and in consequence of a shower of stones a nine days' solemnity of prayer and sacrifice was observed. The reception of Mater Magna was also anxiously discussed. M. Valerius, the member of the deputation who had come in advance, had reported that she would be in Italy almost immediately and a fresh messenger had brought word that she was already at Tarracina. Scipio was ordered to go to Ostia, accompanied by all the matrons, to meet the goddess. He was to receive her as she left the vessel, and when brought to land he was to place her in the hands of the matrons who were to bear her to her destination.

“As soon as the ship appeared off the mouth of the Tiber he put out to sea in accordance with his instructions, received the goddess from the hands of her priestesses, and brought her to land. Here she was received by the foremost matrons of the City, amongst whom the name of Claudia Quinta stands out pre-eminently. According to the traditional account her reputation had previously been doubtful, but this sacred function surrounded her with a halo of chastity in the eyes of posterity. The matrons, each taking their turn in bearing the sacred image, carried the goddess into the temple of Victory on the Palatine. All the citizens flocked out to meet them, censers in which incense was burning were placed before the doors in the streets through which she was borne, and from all lips arose the prayer that she would of her own free will and favor be pleased to enter Rome. The day on which this event took place was 12th April, and was observed as a festival; the people came in crowds to make their offerings to the deity; a lectisternium [7-day citywide feast] was held, and Games were constituted which were known afterwards as the Megalesian.

Magna Mater Worship

Magna Mater altars

The Magna Mater goddess reportedly was served by self-emasculated priests known as galli. Until the emperor Claudius, Roman citizens could not become priests of Cybele, but after that worship of her and her lover Attis took their place in the state cult. One aspect of the cult was the use of baptism in the blood of a bull, a practice later taken over by Mithraism. [Source: Lucretius, “On the Nature of Things,” translation by William Ellery Leonard. Complete version online at MIT classics.mit.edu/Carus/nature_things]

Describing the cult, the Epicurean poet Lucretius (98-c.55 B.C.) wrote in “On the Nature of Things”:

“Wherefore great mother of gods, and mother of beasts,

And parent of man hath she alone been named.

Her hymned the old and learned bards of Greece.

Seated in chariot o'er the realms of air

To drive her team of lions, teaching thus

That the great earth hangs poised and cannot lie

Resting on other earth. Unto her car

They've yoked the wild beasts, since a progeny,

However savage, must be tamed and chid

By care of parents. They have girt about

With turret-crown the summit of her head,

Since, fortressed in her goodly strongholds high,

'Tis she sustains the cities; now, adorned

With that same token, to-day is carried forth,

With solemn awe through many a mighty land,

The image of that mother, the divine.

Her the wide nations, after antique rite,

Do name Idaean Mother, giving her

Escort of Phrygian bands, since first, they say,

From out those regions 'twas that grain began

Through all the world. To her do they assign

The Galli, the emasculate, since thus

They wish to show that men who violate

The majesty of the mother and have proved

Ingrate to parents are to be adjudged

Unfit to give unto the shores of light

A living progeny. The Galli come:

And hollow cymbals, tight-skinned tambourines

Resound around to bangings of their hands;

The fierce horns threaten with a raucous bray;

The tubed pipe excites their maddened minds

In Phrygian measures; they bear before them knives,

Wild emblems of their frenzy, which have power

The rabble's ingrate heads and impious hearts

To panic with terror of the goddess' might.

And so, when through the mighty cities borne,

She blesses man with salutations mute,

They strew the highway of her journeyings

With coin of brass and silver, gifting her

With alms and largesse, and shower her and shade

With flowers of roses falling like the snow

Upon the Mother and her companion-bands.

Here is an armed troop, the which by Greeks

Are called the Phrygian Curetes. Since

“Haply among themselves they use to play

In games of arms and leap in measure round

With bloody mirth and by their nodding shake

The terrorizing crests upon their heads,

This is the armed troop that represents

The arm'd Dictaean Curetes, who, in Crete,

As runs the story, whilom did out-drown

That infant cry of Zeus, what time their band,

Young boys, in a swift dance around the boy,

To measured step beat with the brass on brass,

That Saturn might not get him for his jaws,

And give its mother an eternal wound

Along her heart. And it is on this account

That armed they escort the mighty Mother,

Or else because they signify by this

That she, the goddess, teaches men to be

Eager with armed valour to defend

Their motherland, and ready to stand forth,

The guard and glory of their parents' years.”

Sacred Orgy of Cybele

Magna Mater figure

Catullus (c.84-c.54 B.C.) wrote in Carmina 63: “Over the vast main borne by swift-sailing ship, Attis, as with hasty hurried foot he reached the Phrygian wood and gained the tree-girt gloomy sanctuary of the Goddess, there roused by rabid rage and mind astray, with sharp-edged flint downwards dashed his burden of virility. Then as he felt his limbs were left without their manhood, and the fresh-spilt blood staining the soil, with bloodless hand she hastily took a tambour light to hold, your taborine, Cybele, your initiate rite, and with feeble fingers beating the hollowed bullock's back, she rose up quivering thus to chant to her companions. [Source: Catullus, “The Carmina of Gaius Valerius Catullus,” translated by. Leonard C. Smithers. London. Smithers. 1894]

““Haste you together, she-priests, to Cybele's dense woods, together haste, you vagrant herd of the dame Dindymene, you who inclining towards strange places as exiles, following in my footsteps, led by me, comrades, you who have faced the ravening sea and truculent main, and have castrated your bodies in your utmost hate of Venus, make glad our mistress speedily with your minds' mad wanderings. Let dull delay depart from your thoughts, together haste you, follow to the Phrygian home of Cybele, to the Phrygian woods of the Goddess, where sounds the cymbal's voice, where the tambour resounds, where the Phrygian flutist pipes deep notes on the curved reed, where the ivy-clad Maenades furiously toss their heads, where they enact their sacred orgies with shrill-sounding ululations, where that wandering band of the Goddess flits about: there it is meet to hasten with hurried mystic dance.”

“When Attis, spurious woman, had thus chanted to her comity, the chorus straightway shrills with trembling tongues, the light tambour booms, the concave cymbals clang, and the troop swiftly hastes with rapid feet to verdurous Ida. Then raging wildly, breathless, wandering, with brain distraught, hurries Attis with her tambour, their leader through dense woods, like an untamed heifer shunning the burden of the yoke: and the swift Gallae press behind their speedy-footed leader. So when the home of Cybele they reach, wearied out with excess of toil and lack of food they fall in slumber. Sluggish sleep shrouds their eyes drooping with faintness, and raging fury leaves their minds to quiet ease.

“But when the sun with radiant eyes from face of gold glanced over the white heavens, the firm soil, and the savage sea, and drove away the glooms of night with his brisk and clamorous team, then sleep fast-flying quickly sped away from wakening Attis, and goddess Pasithea received Somnus in her panting bosom. Then when from quiet rest torn, her delirium over, Attis at once recalled to mind her deed, and with lucid thought saw what she had lost, and where she stood, with heaving heart she backwards traced her steps to the landing-place. There, gazing over the vast main with tear-filled eyes, with saddened voice in tristful soliloquy thus did she lament her land:

““Mother-land, my creatress, mother-land, my begetter, which full sadly I'm forsaking, as runaway serfs do from their lords, to the woods of Ida I have hasted on foot, to stay amid snow and icy dens of beasts, and to wander through their hidden lurking-places full of fury. Where, or in what part, mother-land, may I imagine that you are? My very eyeball craves to fix its glance towards you, while for a brief space my mind is freed from wild ravings. And must I wander over these woods far from my home? From country, goods, friends, and parents, must I be parted? Leave the forum, the palaestra, the race-course, and gymnasium? Wretched, wretched soul, it is yours to grieve for ever and ever. For what shape is there, whose kind I have not worn? I (now a woman), I a man, a stripling, and a lad; I was the gymnasium's flower, I was the pride of the oiled wrestlers: my gates, my friendly threshold, were crowded, my home was decked with floral garlands, when I used to leave my couch at sunrise. Now will I live a ministrant of gods and slave to Cybele? I a Maenad, I a part of me, I a sterile trunk! Must I range over the snow-clad spots of verdurous Ida, and wear out my life beneath lofty Phrygian peaks, where stay the sylvan-seeking stag and woodland-wandering boar? Now, now, I grieve the deed I've done; now, now, do I repent!”

Magna Mater votive relief

“As the swift sound left those rosy lips, borne by new messenger to gods' twinned ears, Cybele, unloosing her lions from their joined yoke, and goading, the left-hand foe of the herd, thus speaks: “Come,” she says, “to work, you fierce one, cause a madness urge him on, let a fury prick him onwards till he returns through our woods, he who over-rashly seeks to fly from my empire. On! thrash your flanks with your tail, endure your strokes; make the whole place re-echo with roar of your bellowings; wildly toss your tawny mane about your nervous neck.” Thus ireful Cybele spoke and loosed the yoke with her hand. The monster, self-exciting, to rapid wrath spurs his heart, he rushes, he roars, he bursts through the brake with heedless tread. But when he gained the humid verge of the foam-flecked shore, and spied the womanish Attis near the opal sea, he made a bound: the witless wretch fled into the wild wood: there throughout the space of her whole life a bondsmaid did she stay. Great Goddess, Goddess Cybele, Goddess Dame of Dindymus, far from my home may all your anger be, 0 mistress: urge others to such actions, to madness others hound.”

Christian View of a “Bloody” Magna Mater Ritual

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (A.D. 348-418), a Roman Christian poet, wrote at time when Christianity had become established and “paganism” was caste in an unfavorable light: “The high priestess who is to be consecrated is brought down under ground in a pit dug deep, marvellously adorned with a fillet, binding her festive temples with chaplets, her hair combed back under a golden crown, and wearing a silken toga caught up with Gabine girding. Over this they make a wooden floor with wide spaces, woven of planks with an open mesh; they then divide or bore the area and repeatedly pierce the wood with a pointed tool that it may appear full of small holes.

“Here a huge bull, fierce and shaggy in appearance, is led, bound with flowery garlands about its flanks, and with its horns sheathed---its forehead sparkles with gold, and the flash of metal plates colors its hair. Here, as is ordained, they pierce its breast with a sacred spear; the gaping wound emits a wave of hot blood, and the smoking river flows into the woven structure beneath it and surges wide. Then by the many paths of the thousand openings in the lattice the falling shower rains down a foul dew, which the priestess buried within catches, putting her head under all the drops.

She throws back her face, she puts her cheeks in the way of the blood, she puts under it her ears and lips, she interposes her nostrils, she washes her very eyes with the fluid, nor does she even spare her throat but moistens her tongue, until she actually drinks the dark gore. Afterwards, the corpse, stiffening now that the blood has gone forth, is hauled off the lattice, and the priestess, horrible in appearance, comes forth, and shows her wet head, her hair heavy with blood, and her garments sodden with it. This woman, all hail and worship at a distance, because the ox's blood has washed her, and she is born again for eternity.”

Magna Mater Taurobolium

Demeter-Eleusian Cult Initiation in Athens

The Lesser Mysteries: Athenian 'flower-month' Anthesterion (February/March) — with 12th Pithoigia 'opening the jars', 13th Choes 'wine amphorae' and 14th Chytrai — was held at Agrai, in Athens, on the south east side of the Ilissos stream, just outside the old walls, where there was a shrine for Demeter (Metroon) and for Artemis. It was said the maiden Oreithyeia was abducted here by Boreas ('North Wind': Death/cold) and ravished. Her companion was Pharmakeia ('user-of-drugs'). [Plato Phaedrus 229c] [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Greater Mysteries:: Athenian 'bull-running' month Boedromion (September-October). On the 13th and 14th Boed., young aristocratic Athenian Ephebes (teens engaged in military training) escorted the 'sacred things' from Eleusis to Athens. The ‘sacred things’ were brought to the Eleusinion, at the west foot of the Acropolis. Their arrival was then reported to the priestess of Athena Polias (City-Athena). The first four days of the festival took place in Athens (15th to 18th): 15th Agrimos ('Gathering'), 16th 'Seaward, Initiates', 17th 'Hither the victims', 18th Epidauria (at Athens), 19th March to Eleusis, 20th Initiation, 21st Plemochoiai

The festival was supervised by the Athenian magistrate, the Basileus ('King'), with two assistants from the Athenian Citizen body and a representative of the Clan Eumolpidai and Clan Kerykes. Initiates had to bathe in the sea and sacrifice a pig to Demeter. The 20-kilometer Procession to Eleusis (14 miles) was led by statue of Iacchos (Bacchus). Participants wore crowns of myrtle on their heads and carried bundles of leaves bound with bacchoi (rings). At night inside a small building called the A naktoron ('King's house' wanax) in the Telesterion ('Hall of Initiation') in Eleusis, the sacred things were placed in baskets (kistai) were 'shown' by the Hierophant

Epopteia ('Beholding') was an optional festival held the year following for Greater Mysteries festival. The Mystai (initiates of the previous year's ceremony) A fresh-cut wheat stalk was 'shown'.”

Demeter-Eleusinian Mystery Cults

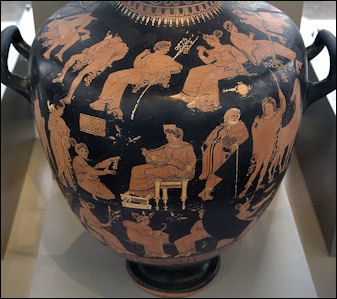

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In classical antiquity, the earliest and most celebrated mysteries were the Eleusinian. At Eleusis, the worship of the agricultural deities Demeter and her daughter Persephone, also known as Kore, was based on the growth cycles of nature. Athenians believed they were the first to receive the gift of grain cultivation from Demeter. [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/]

Eleusinian Caryatid

“Extraordinarily, the goddess herself revealed to them the solemn rites in her honor, as we learn in the Homeric hymn to Demeter, which relates the foundation myth of the Eleusinian cult. Hades abducted Persephone while she was picking flowers with her companions in a meadow and carried her off to the Underworld. After wandering in vain looking for her daughter, Demeter arrived at Eleusis. There the wrath of the distressed mother caused a complete failure of the crops, prompting Zeus to order his brother Hades to return the girl. He cunningly tricked Persephone into eating some pomegranate seeds before leaving, thus condemning her to spend part of the year in the Underworld as his wife and the rest among the living with Demeter.

“During the Great Eleusinia, the public aspect of which culminated in the grand procession from the center of Athens to Eleusis along the Sacred Way, the actions and experiences of the initiates mirrored those of the two goddesses in the sacred drama (drama mystikon). In the early sixth century B.C., the "Queen of the Underworld" persona of Kore was introduced and a nocturnal initiation rite called katabasis was added to the festival: a simulated descent to Hades and ritual search for Persephone. Before the entrance to the Telesterion, the central hall of the sanctuary where the secret rites were performed, priestly personnel holding torches met up with the initiates, who until then were wandering in the dark. At the Eleusinian mysteries, the tension between public and private, conspicuous and secret was inherent in the double nature of the cult. Unlike city-state (polis) religion, participation was restricted to individuals who chose to be initiated, to become mystai. At the same time, it was far more inclusive, being open not only to Athenian male citizens, but to non-Athenians, women, and slaves.” \^/

See Separate Article on the Eleusinian Mysteries

Mysteries for Demeter

Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusia

Pausanias wrote in “Description of Greece” Book II: Corinth (A.D. 160): Celeae, a town near Phlius in the northwestern Peloponnese, “is some five stades distant from the city, and here they celebrate the mysteries in honor of Demeter, not every year but every fourth year. The initiating priest is not appointed for life, but at each celebration they elect a fresh one, who takes, if he cares to do so, a wife. In this respect their custom differs from that at Eleusis, but the actual celebration is modelled on the Eleusinian rites. [Source: Pausanias, “Description of Greece,” with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D. in 4 Volumes. Volume 1.Attica and Cornith, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1918]

“The Phliasians themselves admit that they copy the "performance" at Eleusis. They say that it was Dysaules, the brother of Celeus, who came to their land and established the mysteries, and that he had been expelled from Eleusis by Ion, when Ion, the son of Xuthus, was chosen by the Athenians to be commander-in-chief in the Eleusinian war. Now I cannot possibly agree with the Phliasians in supposing that an Eleusinian was conquered in battle and driven away into exile, for the war terminated in a treaty before it was fought out, and Eumolpus himself remained at Eleusis. But it is possible that Dysaules came to Phlius for some other reason than that given by the Phliasians. I do not believe either that he was related to Celeus, or that he was in any way distinguished at Eleusis, otherwise Homer would never have passed him by in his poems. For Homer is one of those who have written in honor of Demeter, and when he is making a list of those to whom the goddess taught the mysteries he knows nothing of an Eleusinian named Dysaules. These are the verses:

‘She to Triptolemus taught, and to Diocles, driver of horses,

Also to mighty Eumolpus, to Celeus, leader of peoples,

Cult of the holy rites, to them all her mystery telling.

At all events, this Dysaules, according to the Phliasians, established the mysteries here, and he it was who gave to the place the name Celeae. I have already said that the tomb of Dysaules is here. So the grave of Aras was made earlier, for according to the account of the Phliasians Dysaules did not arrive in the reign of Aras, but later. For Aras, they say, was a contemporary of Prometheus, the son of Iapetus, and three generations of men older than Pelasgus the son of Arcas and those called at Athens aboriginals. On the roof of what is called the Anactorum they say is dedicated the chariot of Pelops.

Demeter-Eleusian Cult Initiation in Athens

procession of initiates

The Lesser Mysteries: Athenian 'flower-month' Anthesterion (February/March) — with 12th Pithoigia 'opening the jars', 13th Choes 'wine amphorae' and 14th Chytrai — was held at Agrai, in Athens, on the south east side of the Ilissos stream, just outside the old walls, where there was a shrine for Demeter (Metroon) and for Artemis. It was said the maiden Oreithyeia was abducted here by Boreas ('North Wind': Death/cold) and ravished. Her companion was Pharmakeia ('user-of-drugs'). [Plato Phaedrus 229c] [Source: John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Greater Mysteries:: Athenian 'bull-running' month Boedromion (September-October). On the 13th and 14th Boed., young aristocratic Athenian Ephebes (teens engaged in military training) escorted the 'sacred things' from Eleusis to Athens. The ‘sacred things’ were brought to the Eleusinion, at the west foot of the Acropolis. Their arrival was then reported to the priestess of Athena Polias (City-Athena). The first four days of the festival took place in Athens (15th to 18th): 15th Agrimos ('Gathering'), 16th 'Seaward, Initiates', 17th 'Hither the victims', 18th Epidauria (at Athens), 19th March to Eleusis, 20th Initiation, 21st Plemochoiai

The festival was supervised by the Athenian magistrate, the Basileus ('King'), with two assistants from the Athenian Citizen body and a representative of the Clan Eumolpidai and Clan Kerykes. Initiates had to bathe in the sea and sacrifice a pig to Demeter. The 20-kilometer Procession to Eleusis (14 miles) was led by statue of Iacchos (Bacchus). Participants wore crowns of myrtle on their heads and carried bundles of leaves bound with bacchoi (rings). At night inside a small building called the A naktoron ('King's house' wanax) in the Telesterion ('Hall of Initiation') in Eleusis, the sacred things were placed in baskets (kistai) were 'shown' by the Hierophant

Epopteia ('Beholding') was an optional festival held the year following for Greater Mysteries festival. The Mystai (initiates of the previous year's ceremony) A fresh-cut wheat stalk was 'shown'.”

Dionysos Mystery Cults

Kiki Karoglou of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “While at Eleusis and other sanctuary-based cults participation in the mysteries was a single transformative event, the initiates of the Bacchic mysteries met repeatedly. Bacchus was an epithet of the god Dionysos, possibly referring to the namesake branch carried by his initiates, who also wore headbands tied into a bow. In myth, Dionysos is followed by his thiasos, a retinue of satyrs and maenads who wear fawn skins, are crowned by wreaths of ivy or oak, and hold thyrsoi: giant fennel stalks covered with ivy and topped by pine cones, often wound with fillets. Bacchic thiasoi existed from at least the fifth century B.C. onward. They were small voluntary organizations of worshippers, sponsored in Roman times by wealthy patrons. Secret activities, called teletai or orgia, took place in the mountains, where the Bacchoi engaged in ecstatic dancing, singing, revelry, and even eating raw meat (homophagia). The wine-induced Bacchic frenzy was seen as a temporary madness that transported them from civilization to wilderness, both literally and metaphorically [Source: Kiki Karoglou, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2013, metmuseum.org \^/] \^/

“The followers of Dionysos derived many of their eschatological beliefs and ritual prescriptions from Orphic literature, a corpus of theogonic poems and hymns. The mythical Thracian poet Orpheus, the archetypical musician, theologian, and mystagogue, was credited with the introduction of the mysteries into the Greek world. According to myth, Orpheus' reclusion that followed his unsuccessful attempt to bring back his wife Eurydice from the Underworld or, alternatively, his invention of homosexuality brought about the tragic, violent death he suffered at the hands of Thracian women. \^/

“References by Herodotus and Euripides attest to the existence of certain Bacchic-Orphic beliefs and practices: itinerant religion specialists and purveyors of secret knowledge, called Orpheotelestai, performed the teletai, private rites for the remission of sins. For the Orphics, Dionysos was a savior god with redeeming qualities. He was the son of Zeus and Persephone and successor to his throne. When the Titans attacked and dismembered the baby Dionysos, Zeus in retaliation blazed the perpetrators with his thunderbolt. From the Titans' ashes the human race was born, burdened by the horrific inheritance of an "original sin." Similarly to the Pythagoreans, the Orphics did not consume meat and were not to be buried in woolen garments. Archaeological finds from southern Italy, northern Greece, the Pontic area, and Crete provide important evidence for the Bacchic-Orphic mysteries: to ensure personal salvation and eternal bliss in the afterlife, objects such as the famed Derveni papyrus, inscribed bone plaques and gold leaves (lamellae), or gilded mouth-pieces were buried with the initiates.” \^/

Bacchanal sarcophagus

Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

James W. Jackson wrote in the Villa of Mysteries website: “This villa, built around a central peristyle court and surrounded by terraces, is much like other large villas of Pompeii. However, it contains one very unusual feature; a room decorated with beautiful and strange scenes. This room, known to us as "The Initiation Chamber," measures 15 by 25 feet and is located in the front right portion of the villa. [Source: James W. Jackson, Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii website]

“The term "mysteries" refers to secret initiation rites of the Classical world. The Greek word for "rite" means "to grow up". Initiation rites, then, were originally ceremonies to help individuals achieve adulthood. The rites are not celebrations for having passed certain milestones, such as our high school graduation, but promote psychological advancement through the stages of life. Often a drama was enacted in which the initiates performed a role. The drama may include a simulated death and rebirth; i.e., the dying of the old self and the birth of the new self. Occasionally the initiate was guided through the ritual by a priest or priestess and at the end of the ceremony the initiate was welcomed into the group.

“The chamber is entered through an opening located between the first and last scenes of the fresco The fresco images seem to part of a ritual ceremony aimed at preparing privileged, protected girls for the psychological transition to life as married women. The frescoes in the Villa of Mysteries provide us the opportunity to glimpse something important about the rites of passage for the women of Pompeii. But as there are few written records about mystery religions and initiation rites, any iconographic interpretation is bound to be flawed. In the end we are left with the wonderful frescoes and the mystery. Nevertheless, an interpretation is offered, see if you agree or disagree.

“At the center of the frescoes are the figures of Dionysus, the one certain identification agreed upon by scholars, and his mother Semele (other interpretations have the figure as Ariadne). As he had been for Greek women, Dionysus was the most popular god for Roman women. He was the source of both their sensual and their spiritual hopes.

Scenes in Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

James W. Jackson wrote in the Villa of Mysteries website: “Scene 1: The action of the rite begins with the initiate or bride crossing the threshold as the preparations for the rites to begin. Her wrist is cocked against her hip. Is she removing her scarf? Is she listening to the boy read from the scroll? Is she pregnant? The nudity of the boy may signify that he is divine. Is he reading rules of the rite? He wears actor's boots, perhaps indicating the dramatic aspect of the rites. The officiating priestess (behind the boy) holds another scroll in her left hand and a stylus in her right hand. Is she prepared to add the initiate's name to a list of successful initiates?” Later, “The initiate, now more lightly clad, carries an offering tray of sacramental cake. She wears a myrtle wreath. In her right hand she holds a laurel sprig. [Source: James W. Jackson, Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii website]

“Scene 2: A priestess, wearing a head covering and a wreath of myrtle removes a covering from a ceremonial basket held by a female attendant. Speculations about the contents of the basket include: more laurel, a snake, or flower petals. A second female attendant wearing a wreath, pours purifying water into a basin in which the priestess is about to dip a sprig of laurel. Mythological characters and music are introduced into the narrative. An aging Silenus plays a ten-string lyre resting on a column.

“Scene 3: A young male satyr plays pan pipes, while a nymph suckles a goat. The initiate is being made aware of her close connection with nature. This move from human to nature represents a shift away from the conscious human world to our preconscious animal state. In many rituals, this regression, assisted by music, is requisite to achieving a psychological state necessary for rebirth and regeneration. The startled initiate has a glimpse of what awaits her in the inner sanctuary where the katabasis will take place. This is her last chance to save herself by running away. Perhaps some initiates did just that. The next scene provides hints about what both frightens and awaits the initiate.

Villa of Mysteries at Pompeii

“Scene 4: “The Silenus looks disapprovingly at the startled initiate as he holds up an empty silver bowl. A young satyr gazes into the bowl, as if mesmerized. Another young satyr holds a theatrical mask (resembling the Silenus) aloft and looks off to his left. Some speculate that the mask rather than the satyr's face is reflected in the silver bowl. So, looking into the vessel is an act of divination: the young satyr sees himself in the future, a dead satyr. The young satyr and the young initiate are coming to terms with their own deaths. In this case the death of childhood and innocence. The bowl may have held Kykeon, the intoxicating drink of participants in Orphic-Dionysian mysteries, intended for the frightened initiate.

“Scene 5: This scene is at the center of both the room and the ritual. Dionysus sprawls in the arms of his mother Semele. Dionysus wears a wreath of ivy, his thyrsus tied with a yellow ribbon lies across his body, and one sandal is off his foot. Even though the fresco is badly damaged, we can see that Semele sits on a throne with Dionysus leaning on her. Semele, the queen, the great mother is supreme.

“Scene 6: The initiate, carrying a staff and wearing a cap, returns from the night journey. What has happened is a mystery to us. But in similar rituals the confused, and sometimes drugged initiate emerges like an infant at birth, from a dark place to a lighted place. She reaches for a covered object sitting in a winnowing basket, the liknon. The covered object is taken by many to be a phallus, or a herm. To the right is a winged divinity, perhaps Aidos. Her raised hand is rejecting or warding off something. She is looking to the left and is prepared to strike with a whip. Standing behind the initiate are two figures of women, unfortunately badly damaged. One woman (far left) holds a plate with what appear to be pine needles above the initiate's head. The apprehensive second figure is drawing back.

“Scene 7: The two themes of this scene are torture and transfiguration, the evocative climax of the rite. Notice the complete abandonment to agony on the face of the initiate and the lash across her back. She is consoled by a woman identified as a nurse. To the right a nude women clashes celebratory cymbals and another woman is about to give to the initiate a thyrsus, symbolizing the successful completion of the rite.

“Scene 8: This scene represents an event after the completion of the ritual drama. The transformed initiate or bride prepares, with the help of an attendant, for marriage. A young Eros figure holds a mirror which reflects the image of the bride. Both the bride and her reflected image stare out inquiringly at us, the observers.

“Scene 9: The figure above has been identified as: the mother of the bride, the mistress of the villa, or the bride herself. Notice that she does wear a ring on her finger. If she is the same female who began the dramatic ritual as a headstrong girl, she has certainly matured psychologically. Scene 10: Eros, a son of Chronos or Saturn, god of Love, is the final figure in the narrative.”

Livy’s Account of Dionysiac Frenzy in Italy

Describing the Senatusconsultum de Bacchanalibus in Italy, Livy wrote in “History of Rome”, Book 39. 8-19 (186 B.C.): "During the following year, the consuls Spurius Postumius Albinus and Quintus Marcius Philippus were diverted from the army and the administration of wars and provinces to the suppression of an internal conspiracy.... A lowborn Greek came first into Etruria [Tuscany], a man who was possessed of none of the numerous arts which [the Greeks] have introduced among us for the cultivation of mind and body. He was a mere sacrificer and a fortuneteller–not even one of those who imbue men’s minds with error by preaching their creed in public and professing their business openly; instead he was a hierophant of secret nocturnal rites. At first these were divulged to only a few. Then they began to spread widely among men, and women. To the religious content were added the pleasures of wine and feasting–to attract a greater number. [Source: (Livy History of Rome Book 39. 8-19: 186 B.C., John Adams, California State University, Northridge (CSUN), “Classics 315: Greek and Roman Mythology class]

Poussin's Bacchanal

“When they were heated with wine and all sense of modesty had been extinguished by the darkness of night and the commingling of males with females, tender youths with elders, then debaucheries of every kind commenced. Each had pleasures at hand to satisfy the lust to which he was most inclined. Nor was the vice confined to the promiscuous intercourse of free men and women! False witnesses and evidence, forged seals and wills, all issued from this same workshop. Also, poisonings and murders of kin, so that sometimes the bodies could not even be found for burial. Much was ventured by guile, more by violence, which was kept secret, because the cries of those calling for help amid the debauchery and murder could not be heard through the howling and the crash of drums and cymbals.

“This pestilential evil spread from Etruria [Tuscany] to Rome like a contagious disease. At first, the size of the city, with room and tolerance for such evils, concealed it. But information at length reached the Consul Postumus.... Postumus laid the matter before the Senate, setting forth everything in detail-first the information he had received; and then, the results of his own investigations. The Senators were seized by a panic of fear, both for the public safety (lest these secret conspiracies and nocturnal gatherings contain some hidden harm or danger) and for themselves individually (lest some relatives be involved in this vice). They decreed a vote of thanks to the Consul for having investigated the matter so diligently and without creating any public disturbance. Then they commissioned the consuls to conduct a special inquiry into the Bacchanalia and nocturnal rites. They directed them to see to it that Aebutius and Faecenia suffer no harm for the evidence they had given, and to offer rewards to induce other informers to come forward; the priests of these rites, whether men or women, were to be sought out not only in Rome but in every forum and conciliabulum, so that they might ‘be at the disposal of’ the consuls. Edicts were to be published in the City of Rome and throughout Italy, ordering that none who had been initiated into the Bacchic rites should be minded to gather or come together for the celebration of these rites, or to perform any such ritual. And above all, an inquiry was to be conducted regarding those persons who had gathered together or conspired to promote debauchery or crime.

“These were the measures decreed by the Senate. The consuls ordered the Curule Aediles to search out all the priests of this cult, apprehend them, and keep them under house arrest for the inquiry; the Plebeian Aediles were to see that no rites were performed in secret. The Three Commissioners (Tresviri Capitales) were instructed to post watches throughout the City, to see to it that no nocturnal gatherings took place and to take precautions against fires. And to assist them, five men were assigned on each side of the Tiber, each to take responsibility for the buildings in his own district....

“The Consuls then ordered the Decrees of the Senate to be read [in the Assembly] and they announced a reward to be paid to anyone who brought a person before them, or, in the absence of the person, reported his name. If anyone took flight after being named, the Consuls would fix a day for him to answer the charge, and on that day, if he failed to answer when called, he would be condemned in absentia. If any person were named who was beyond the confines of Italy at the time, they would set a more flexible date, in the event that he should wish to come to Rome and plead his case. Next, they ordered by edict that no person be minded to sell or buy anything for the purpose of flight; that no one harbor, conceal, or in any way assist fugitives.... Guards were posted at the gates, and during the night following the disclosure of the affair in the Assembly, many who tried to escape were arrested by the Tresviri Capitales and brought back. Many names were reported, and some of these, women as well as men, committed suicide. It was said that more than 7,000 men and women were implicated in the conspiracy.”

“Next the Consuls were given the task of destroying all places of Bacchic worship, first at Rome, and then throughout the length and bradth of Italy–except where there was an ancient altar or a sacred image. For the future, the Senate decreed that there should be NO Bacchic rites in Rome or in Italy. If any person considered such worship a necessary observance, that he could not neglect without fear of committing sacrilege, then he was to make a declaration before the Praetor Urbanus, and the Praetor would consult the Senate. IF permission were granted by the Senate (with at least one hundred senators present), he might perform that rite–provided that no more than five persons took part in the ritual, and that they had no common fund and no master or priest...."”

Bacchanal

Dionysius in the Bacchae by Euripides

Euripides wrote in “The Bacchae,” 677-775: The Messenger said: “The herds of grazing cattle were just climbing up the hill, at the time when the sun sends forth its rays, warming the earth. I saw three companies of dancing women, one of which Autonoe led, the second your mother Agave, and the third Ino. All were asleep, their bodies relaxed, some resting their backs against pine foliage, others laying their heads at random on the oak leaves, modestly, not as you say drunk with the goblet and the sound of the flute, hunting out Aphrodite through the woods in solitude. [Source: Euripides. “The Tragedies of Euripides,” translated by T. A. Buckley. Bacchae. London. Henry G. Bohn. 1850.

“Your mother raised a cry, standing up in the midst of the Bacchae, to wake their bodies from sleep, when she heard the lowing of the horned cattle. And they, casting off refreshing sleep from their eyes, sprang upright, a marvel of orderliness to behold, old, young, and still unmarried virgins. First they let their hair loose over their shoulders, and secured their fawn-skins, as many of them as had released the fastenings of their knots, girding the dappled hides with serpents licking their jaws. And some, holding in their arms a gazelle or wild wolf-pup, gave them white milk, as many as had abandoned their new-born infants and had their breasts still swollen. They put on garlands of ivy, and oak, and flowering yew. One took her thyrsos and struck it against a rock, from which a dewy stream of water sprang forth. Another let her thyrsos strike the ground, and there the god sent forth a fountain of wine. All who desired the white drink scratched the earth with the tips of their fingers and obtained streams of milk; and a sweet flow of honey dripped from their ivy thyrsoi; so that, had you been present and seen this, you would have approached with prayers the god whom you now blame.

“We herdsmen and shepherds gathered in order to debate with one another concerning what strange and amazing things they were doing. Some one, a wanderer about the city and practised in speaking, said to us all: “You who inhabit the holy plains of the mountains, do you wish to hunt Pentheus' mother Agave out from the Bacchic revelry and do the king a favor?” We thought he spoke well, and lay down in ambush, hiding ourselves in the foliage of bushes. They, at the appointed hour, began to wave the thyrsos in their revelries, calling on Iacchus, the son of Zeus, Bromius, with united voice. The whole mountain revelled along with them and the beasts, and nothing was unmoved by their running.