ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EDUCATION

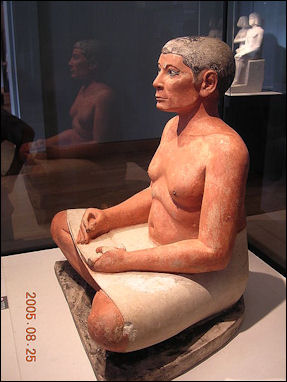

scribe Most people were illiterate. Most of people that learned to read or were educated were nobles and scribes.

Educated Egyptians often learned to read at the age of four. The pharaohs went to the equivalent of exclusive private schools with the children of government officials, nobility and bureaucrats. The students learned to recognize and pronounce several hundred hieroglyphics, then they were taught arithmetic and finally writing. A writing kit consisted of reeds and a palette of solid inks. Papyrus, the material they wrote on, was made was made of the pressed fibrous material of a plant, and only the richest people in Egypt could afford it.♀

Scribe school could be pretty tough. Describing his methods one instructor wrote: “The ear of a boy is on his back. He listens when he is beaten.” After school, in their free time, young Egyptian nobles wrestled and swam in the Nile. If they were good their fathers taught them how to hunt hare, gazelle, ibex and antelope.♀

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Egyptian History (32 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Religion (24 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Life and Culture (36 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Government, Infrastructure and Economics (24 articles) factsanddetails.com.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Ancient Egypt Magazine ancientegyptmagazine.co.uk; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Egyptian Study Society, Denver egyptianstudysociety.com; The Ancient Egypt Site ancient-egypt.org; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Education and Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The main purpose of education and apprenticeship in ancient Egypt was the training of scribes and of specialist craftsmen. The result of this profession-oriented educational system was restricted accessibility to schooling, most probably favoring male members of the Egyptian elite. Basic education offered in Egyptian local schools consisted of the teaching of language, mathematics, geography, and of other subjects appropriate for the preparation of potential scribes who were destined to work in local and national Egyptian institutions, such as the palace or the temples. The evidence for the existence of such an educational system in ancient Egypt comes mainly in the form of school exercises, schoolbooks, and references found in literary and documentary texts. There is comparatively less evidence, however, for the role of apprenticeship, which was a pedagogical method employed mainly for the training of craftsmen or for advanced and specialized education, such as that needed to become a priest. Although the main elements of pedagogy probably remained as such throughout Egyptian history, it is likely that foreign languages were taught from the New Kingdom onwards, culminating in the bilingual Egyptian-Greek education of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Like modern educational systems, ancient Egyptian education prepared the young members of middle and upper classes for entering the labor force of the country and actively participating in various professions and duties related to the civil, priestly, and military spheres. However, unlike education nowadays, the Egyptian school system mainly offered basic and rarely advanced training. Hence, there was probably no Egyptian equivalent to a modern university with its broad educational horizons and its large diversity of specializations. Also, unlike modern educational standards according to which schooling is in most countries a prerequisite for most professions and careers, the Egyptian local school focused primarily on the preparation of scribes and officials before they joined the complex system of local or national bureaucracy. Together with the priesthood, these were the main, highly- esteemed professions available for those who completed schooling.

“The narrow perspectives Egyptian schooling kept resulted in a limited curriculum and probably also in limited approaches to study material. Although such limitations would suggest a canonized model for Egyptian education, its program and curricula most likely allowed considerable space for local variation—given that there was no central authority for controlling the function of Egyptian schools, since there is no evidence that the palace was much involved in the shaping and maintenance of schools. The lack of a nationally organized system in schooling probably also resulted in education’s minor involvement in the building of a national identity for Egyptian students. By contrast, modern educational systems are designed and checked by the national authorities and are meant to contribute to the shaping and maintenance of a national identity.

“When one attempts to discover and re- construct the educational system of an ancient civilization, one seeks, first, evidence for the existence of schools. This can be in the form of: a) archaeological traces of school activity in specific localities; b) products of school activity, such as schoolbooks or school exercises; and c) references to specific schools or to a more general school education in literary or documentary texts. Second, in order to better understand the way the educational system functioned within an ancient society, one can try to identify the locality of specific schools, examining their spatial relationship with a nearby community or other institutions. In this way, one can consider the schools’ potential contact with other aspects of an ancient society, as well as their potential role in the life and development of that society.”

Education Versus Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The term “education” is used here, as in most related Egyptological studies, to denote a social institution (or an educational system) rather than a general idea encompassing all forms of teaching and learning. Thus, by definition, the study of ancient Egyptian education excludes the upbringing of children at home. The main reason for this exclusion is that there is very limited evidence for the way children were educated at home and for the relationship between home and school education. However, it must be noted that home education was probably a pedagogical method as important as schooling. The majority of the working population, including agricultural workers and local craftsmen, probably received their training within a domestic context, rather than at school. The existence of such a household/family-related training context is implied in evidence from Deir el- Medina, suggesting family connections between various groups of craftsmen (cf. the studies on woodcutters and potters). The same may have applied, to a certain extent, even to scribe candidates, since family relations between succeeding scribes are widely attested. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The study of ancient Egyptian education focuses on the function of the Egyptian schools, which aimed at providing the youth with a basic knowledge in a variety of subjects, such as language and mathematics, as well as at teaching ethics and rules of everyday conduct. The main term employed to denote “education” in the ancient Egyptian language read sbAyt and meant “instruction” with a connotation of “punishment”. This was the same term that featured in the titles of Egyptian works of wisdom known as “Instructions”—a fact that may suggest a pedagogical use of such literary works. Along with sbAyt, the term mtrt was also employed to denote the sense of “instruction,” this time with a connotation of “witnessing” or “personal experience.” The latter term was mainly used in the Late Period, but a semantic difference between mtrt and sbAyt has not been detected.

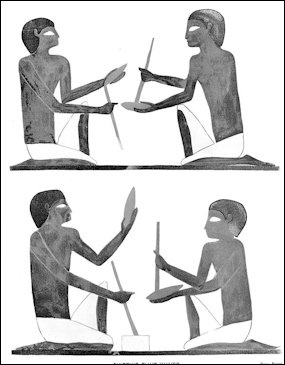

“In contrast to “education,” whose conventional definition, in the case of this essay, covers aspects of basic training received at school, “apprenticeship” is a term that usually refers to a specific method of instruction, namely the instruction offered by a single teacher to a single or a small number of students on one or more specialized subjects or skills. This was a very popular educational method that was employed mainly when advanced training was sought out in order to develop some of the aspects of the curricula of Egyptian schools, such as writing or mathematics, or to introduce new subjects and skills, such as the study of religious texts or the learning of a craft. In addition, apprenticeship was a manner of instruction that was probably also used in some local Egyptian schools even for basic training— perhaps due to the small number of teachers and students available.

“The term most probably denoting apprenticeship read Xrj-a, which literally meant “under the arm/control of,” while the expertteacher was called either nb, “master,” or jtj, “father.” The latter is a term employed mainly in literary contexts to imply a close father-son relationship for that between an instructor and his audience. Thus, for instance, the title “father” is often used in didactic texts, denoting the author of the instruction and teacher of an audience that has still much to learn: ‘Beginning of the sayings of excellent discourse spoken by the Prince….Ptahhotep, in instructing the ignorant to understand and be up to the standard of excellent discourse…So he spoke to his son.’ [Instruction of Ptahhotep]”

School Exercises in Ancient Egypt

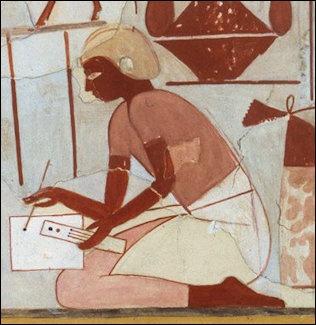

scribe palette and tablet

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “In the case of ancient Egypt, we have so far: 1) numerous copies of school exercises surviving mainly on pottery or stone ostraca (a potsherd used as a writing surface), on wooden or stone tablets, or on small papyrus fragments, coming from a great variety of localities, and dating to almost all phases of Egyptian history; 2) a considerable number of copies of schoolbooks, such as the Middle Kingdom standard version of a schoolbook known as Kemit, “the complete one” or “the summary”; and 3) a large number of references to school activity and educational methods in a range of textual sources from biographical inscriptions to the content of schoolbooks themselves, such as, for instance, a reference to the copying of one chapter per day as discussed by Fischer-Elfert. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian school exercises vary from basic exercises of grammar and orthography to copies of actual literary or documentary texts. There is a certain degree of difficulty in distinguishing between “professional” copies of texts produced by scribes and student copies produced in schools. In most of the cases, what determines whether a text is a student product are the material used as writing surface, the context of the artifact, as well as the style of writing and the contents. Hence, for instance, a school exercise, as mentioned above, was most frequently inscribed on pottery or stone ostraca that were useless otherwise. As far as the context is concerned, school exercises tend to be found in clusters, reflecting a massive use by a group of students and teachers. The location, however, of such quantities of easily moveable material is seldom used to locate an Egyptian school, a task that has so far proven to be very difficult (see below). Finally, the most defining characteristics of a school exercise are the contents of the inscribed text, which in most cases was in the form of a list of words or phrases, as well as the style of writing, which was mostly crude, full of mistakes, and corrections.

“In the case of apprenticeship in ancient Egypt, the available evidence concerns mainly the training of draftsmen and consists of: a) practice ostraca, and b) textual references to artisan training. As with school exercises, practice material can be identified as such due to their crude drawings and the fact that they were painted on ostraca.”

Schools and Their Place in Egyptian Society

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “The term probably used by the Egyptians to refer to a school, as an educational institute rather than a certain space in which teaching was taking place, read pr-anx, “house of life”. In addition, there is the less commonly employed term at-sbA, “house of instruction,” which could denote the school as a space. The meaning of pr-anx is still debated, since scholarly circles are divided between its translation as “school” and as “scriptorium” (that is, the space in which scribes worked— studying, producing, and copying various texts) or “university” (in the sense of an institute of advanced learning in contrast to the basic teaching offered in a common school). The pr-anx in the sense of a scriptorium is closely associated with the function of the Egyptian temple, given that most of the major temples included libraries and archives that were probably managed and maintained by scribes, the primary product of school education (for the existence of temple libraries and archives). However, there is very little evidence for the exact locations of the pr-anx or any other space used for teaching. Such evidence points towards the existence of schools, for instance, around the Ramesseum, at Deir el-Medina, and at the Mut temple in Karnak. No exact locations can be identified, however, mainly because schooling in Egypt probably took place outdoors and its location was not always fixed. References to the existence of a pr-anx vary from titles revealing a connection between administrative positions and school activity to actual references to a pr-anx in association with the life and activities of certain individuals. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

scribe's palette

“It is this connection to specific individuals that has led to the Egyptological consensus that not all individuals had access to a school education. Instead, it seems that school education was primarily for the elite and mostly for the male members of the Egyptian society, who were destined to work for the main Egyptian socio-political and religious institutions, such as the palace, the treasury, or the temple. It should be noted here that, although many priests also bore the title of the scribe, no school texts make direct references to the priestly profession as a goal of education. Perhaps this suggests that the priestly duties were taught after school, as part of an advanced apprenticeship in a temple, or that the children who were destined to become priests were trained in separate, special schools. The “be-a-scribe” orientation of Egyptian education is at the heart of most of the discovered Egyptian schoolbooks. Thus, for instance, in the Ramesside miscellany of Papyrus Lansing one encounters a number of short texts praising the scribal profession: ‘Befriend the scroll, the palette. It pleases more than wine. Writing for him who knows it is better than all other professions. It pleases more than bread and beer, more than clothing and ointment. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the West.’ [Papyrus BM 9994, 2,2 - 2,4]

“Judging from the various references to education and literacy made in Egyptian literary works, one could deduce that being a school graduate was, indeed, highly esteemed in Egyptian society. An example of such references made in Egyptian “Instructions” (that is, didactic works mostly ascribed to a famous sage and discussing, in the form of short sayings and admonitions, general matters of life and moral principles) is: ‘One will do all you say, If you are versed in writings; Study the writings, put them in your heart, Then all your words will be effective. Whatever office a scribe is given, He should consult the writings.’ [The Instruction of Any, lines 7,4 - 7,5]

“The general style of such literary references to education is well illustrated in this example: education is praised in connection with the scribal profession and its high status in Egyptian society. Hence, one may say that such references are really made by scribes (that is, the authors of such compositions) about the value of their own profession, addressing other scribes or students who are to follow the scribal profession. In other words, this is probably a dialogue between members of the same circle, reflecting little about the general appreciation of education among members of Egyptian society who have not gone through a scribal training.

“The apparent limited accessibility to schooling in ancient Egypt has also been one of the reasons some scholars have argued that literacy in most phases of Egyptian history was restricted to a very low percentage of the population, in some cases amounting only to 1 percent. Estimating degrees of literacy in ancient Egypt is, however, a very difficult task. Also, although nowadays literacy equals education, in ancient Egypt most men and women would have been illiterate, due to the limited orientation and accessibility of school education; but that does not necessarily mean that they were uneducated too, since home education and craftsman apprenticeship would train them in areas of specialized knowledge that did not require knowledge of writing or reading. Such home education was also likely for women, for whom there is no solid evidence that they could ever enter schools and be trained to read and write.

“At the same time, there may be some exceptions to the rule of education accessibility according to social status. Hence, for example, in the Middle Kingdom Instruction of Dua-Khety, or the Satire of the Trades as it is often also called, Dua-Khety, who apparently did not hold any important positions in his hometown, escorts his son to the 12th Dynasty Egyptian capital (probably near el-Lisht) where his son is to be admitted to the scribal school together with the children of the elite. Given that there is no reference to a special permission or reward granted to Dua-Khety, this situation seems to reflect an open admission to such schools, including children of lower classes, although it should probably be best taken simply as a piece of literary fiction.”

School Curriculum and Teaching Methods in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “Egyptian pupils entered school probably at the age of four or five and there they were mainly taught how to read and write (including the rules of rhetoric and proper speech), geography, mathematics, and geometry. In addition, there is some evidence for the learning of foreign languages in New Kingdom schools, a fact that historically corresponds to the era of Egyptian imperialism and of the extension of Egyptian foreign relations. This evidence, however, which includes, for example, lists of foreign words or names, is far from conclusive, since it shows more an acquaintance with foreign vocabulary, possibly used in Egyptian texts, rather than mastery over a foreign language. Nevertheless, the occasional use of foreign languages in Egyptian administration was surely a result of some training in foreign languages that could have taken place either in the Egyptian capital or in foreign schools. In addition to these subjects, sports, music, and other arts could have also featured in Egyptian education. The evidence for the treatment of such subjects is, however, scarce. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The first script an Egyptian pupil learnt how to read and write was probably hieratic, which was later (ca. fourth century B.C. onwards) replaced by Demotic. These were the scripts the pupils used to practice writing letters and various types of administrative documents. They were also exposed to literary works, whose language and style often differ from those used in documentary texts. That was the case, for example, in the New Kingdom, when older literary works in Middle Egyptian were studied in school along with works written in Late Egyptian. The pupil was taught language by doing a lot of spelling and grammar exercises, writing passages dictated by the teacher, and copying parts of real or model documentary and literary texts. Such model texts are found in the so-called “miscellanies”, which could be compilations made by teachers for classroom use. Given that some of the texts copied in schools were instructive, teaching mainly about general ethics, the Egyptian pupil was educated also through the study of the contents of such didactic texts. Probably at a later stage, the pupils learnt how to read and write hieroglyphs, the main script for monumental and archaizing writing during most periods of Egyptian history.

“An exemplary educational career of an elite child, who was to become high priest of Amun at Karnak, is described in the biographical texts inscribed on two block statues of Bakenkhons, now in Cairo and Munich. In these texts Bakenkhons mentions among other things: ‘I spent 4 years as an excellent youngster. I spent 11 years as a youth, as a trainee stable-master.’ [Munich statue, Gl. WAF 38, back pillar] ‘I came out from the room of writing in the temple of the lady of the sky as an excellent youngster. I was taught to be a wab-priest in the domain of Amun.’ [Cairo statue, Cairo CG 42155, back pillar (translated in Frood 2007: 43)]

“In contrast to the considerable amount of evidence available for basic school education in ancient Egypt, there is much less evidence for apprenticeship in advanced or special subjects and skills. Such evidence includes, for example, painted ostraca from Deir el-Medina that could have been made by artisan apprentices in situ. Probable references to such young apprentices are made in other ostraca from Deir el-Medina. Finally, there is also some evidence of the manner in which temple musicians were trained. Overall, the method of knowledge transfer through apprenticeship in Pharaonic Egypt was most likely informal and circumstantial, based not so much upon a uniform curriculum but rather upon the personal choices of the experienced professional who took over the education of his potential successors. The close relationship between artisan apprenticeship and school education is evident in the case of a number of tombs, in the context of which school exercises have been discovered. This evidence might indicate that Egyptian students were learning how to read and write by using the material inscribed on tomb walls. After all, tombs in ancient Egypt probably also functioned as places where important works of literature were meant to be preserved. In such cases, the artisan master who was overseeing the works in tombs would probably have also acted more broadly as a teacher.”

Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Education on the Post-Pharaonic Era

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “Historical developments in the educational system of ancient Egypt were probably closely linked to developments in Egyptian language. As mentioned above, hieratic, which was most likely the first script an Egyptian pupil was taught, was replaced at some point during the fourth century B.C. by Demotic. This change took place at the beginning of the Hellenistic era, during which Greek became the official language of the palace in Alexandria. Therefore, in terms of administration, Demotic and Greek co-existed and were used on different occasions, making their mastery a significant requirement for those who wanted to climb the social ladder in Hellenistic and, later, Roman Egypt. As a result, probably most of the local Egyptian schools of those eras added Greek to their curricula. In addition, Greek didaskaleia (“schools”) along with gymnasia (“sport schools”) were founded at most of the sites of Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, as in Alexandria, Antinoopolis, or Krokodilopolis, which included large non- Egyptian populations . The relationship between the Greek gymnasia and the Egyptian schools is not clear, but it seems they were attracting ethnically and/or socially different groups. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“As Demotic was replaced by Coptic from the second century CE onwards and the usage of Egyptian language retreated from the areas of administration and trade, in which Greek and Latin were used instead, the number of schools teaching in Egyptian probably decreased and were limited to Christian monasteries that took over the task of maintaining and developing Coptic language and literature.

“As far as the function of apprenticeship in the post-Pharaonic era is concerned, there is some evidence for children becoming apprentices to experienced craftsmen. Thus, for instance, contracts exist between such craftsmen and parents who sent their children off to learn a craft like weaving or playing a musical instrument. One of these contracts written in Greek and dated to 10 CE reads: “.we will produce our brother named Pasion to stay with you one year from the 40th year of Caesar and to work at the weaver's trade, and...he shall not sleep away or absent himself by day from Pasonis’ house.” [Papyrus Tebtunis 0384]”

Female Education and Literacy in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “It is uncertain, generally, how literate the Egyptian woman was in any period. Baines and Eyre suggest very low figures for the percentage of the literate in the Egypt population, i.e., only about 1 percent in the Old Kingdom (i.e., 1 in 20 or 30 males). Other Egyptologists would dispute these estimates, seeing instead an amount at about 5-10 percent of the population. In any event, it is certain that the rate of literacy of Egyptian women was well behind that of men from the Old Kingdom through the Late Period. Lower class women, certainly were illiterate; middle class women and the wives of professional men, perhaps less so. The upper class probably had a higher rate of literate women. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, middle and upper class women are occasionally found in the textual and archaeological record with administrative titles that are indicative of a literate ability. In the New Kingdom the frequency at which these titles occur declines significantly, suggesting an erosion in the rate of female literacy at that time (let alone the freedom to engage in an occupation). However, in a small number of tomb representations of the New Kingdom, certain noblewomen are associated with scribal palettes, suggesting a literate ability. Women are also recorded as the senders and recipients of a small number of letters in Egypt (5 out of 353). However, in these cases we cannot be certain that they personally penned or read these letters, rather than employed the services of professional scribes. -

“Many royal princesses at court had private tutors, and most likely, these tutors taught them to read and write. Royal women of the Eighteenth Dynasty probably were regularly trained, since many were functioning leaders. Since royal princesses would have been educated, it then seems likely that the daughters of the royal courtiers were similarly educated. In the inscriptions, we occasionally do find titles of female scribes among the middle class from the Middle Kingdom on, especially after the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, when the rate of literacy increased throughout the country. The only example of a female physician in Egypt occurs in the Old Kingdom. Scribal instruction was a necessary first step toward medical training. -

Instruction Letter to Egyptian Scribes

Beginning of the instruction in letter-writing made by the royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen-Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht for his apprentice, the scribe Wenemdiamun: “[The royal scribe] and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen- [Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht speaks to the scribe Wenemdiamun]. [Apply yourself to this] noble profession.... Your will find it useful.... You will be advanced by your superiors. You will be sent on a mission.... Love writing, shun dancing; then you become a worthy official. Do not long for the marsh thicket. Turn your back on throw-stick and chase. By day write with your fingers; recite by night. Befriend the scroll, the palette. It pleases more than wine. Writing for him who knows it is better than all other professions. It pleases more than bread and beer, more than clothing and ointment. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the west. [Source: Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), I, pp. 168-173.

“Young fellow, how conceited you are! You do not listen when I speak. Your heart is denser than a great obelisk, a hundred cubits high, ten cubits thick. When it is finished and ready for loading, many work gangs draw it. It hears the words of men; it is loaded on a barge. Departing from Yebu it is conveyed, until it comes to rest on its place in Thebes. So also a cow is bought this year, and it plows the following year. It learns to listen to the herdsman; it only lacks words. Horses brought from the field, they forget their mothers, Yoked they go up and down on all his majesty's errands. They become like those that bore them, that stand in the stable. They do their utmost for fear of a beating. But though I beat you with every kind of stick, you do not listen. If I knew another way of doing it, I would do it for you, that you might listen. You are a person fit for writing, though you have not yet known a woman. Your heart discerns, your fingers are skilled, your mouth is apt for reciting.

“Writing is more enjoyable than enjoying a basket of [?] and beans; more enjoyable that a mother's giving birth, when her heart knows no distaste. She is constant in nursing her son; her breast is in his mouth every day. Happy is the heart [of] him who writes; he is young each day. The royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen- Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht, speaks to the scribe Wenemdiamun, as follows. You are busy coming and going, and do not think of writing. You resist listening to me; you neglect my teachings.

“You are worse than the goose of the shore that is busy with mischief. It spends the summer destroying the dates, the winter destroying the seed-grain. It spends the balance of the year in pursuit of the cultivators. It does not let seed be cast to the ground without snatching it.... One cannot catch it by snaring. One does not offer it in the temple. The evil, shape-eyed bird that does no work! You are worse than the desert antelope that lives by running. It spends no day in plowing. Never at all does it tread on the threshing-floor. It lives on the oxen's labor, without entering among them. But though I spend the day telling you "Write," it seems like a plague to you. Writing is very pleasant!....

“See for yourself with your own eye. The occupations lie before you. The washerman's day is going up, going down. All his limbs are weak, [from] whitening his neighbor's clothes every day, from washing their linen. The maker of pots is smeared with soil, like one whose relations have died. His hands, his feet are full of clay; he is like one who lives in the bog. The cobbler mingles with vats. His odor is penetrating. His hands are red with madder, like one who is smeared with blood. He looks behind him for the kite, like one whose flesh is exposed. The watchman prepares garlands and polishes vase-stands. He spends a night of toil just as one on whom the sun shines.

“The merchants travel downstream and upstream. They are as busy as can be, carrying goods from one town to another. They supply him who has wants. But the tax collectors carry off the gold, that most precious of metals. The ships' crews from every house [of commerce], they receive their loads. They depart from Egypt for Syria, and each man's god is with him. [But] not one of them says: "We shall see Egypt again!" The carpenter who is in the shipyard carries the timber and stacks it. If he gives today the output of yesterday, woe to his limbs! The shipwright stands behind him to tell him evil things. His outworker who is in the fields, his is the toughest of all the jobs. He spends the day loaded with his tools, tied to his toolbox. When he returns home at night, he is loaded with the toolbox and the timbers, his drinking mug, and his whetstones.

“The scribe, he alone, records the output of all of them. Take note of it! Let me also expound to you the situation of the peasant, that other tough occupation. [Comes] the inundation and soaks him..., he attends to his equipment. By day he cuts his farming tools; by night he twists rope. Even his midday hour he spends on farm labor. He equips himself to go to the field as if he were a warrior. The dried field lies before him; he goes out to get his team. When he has been after the herdsman for many days, he gets his team and comes back with it. He makes for it a place in the field. Comes dawn, he goes to make a start and does not find it in its place. He spends three days searching for it; he finds it in the bog. He finds no hides on them; the jackals have chewed them. He comes out, his garment in his hand, to beg for himself a team.

scribe writing

“When he reaches his field he finds [it?] broken up. He spends time cultivating, and the snake is after him. It finishes off the seed as it is cast to the ground. He does not see a green blade. He does three plowings with borrowed grain. His wife has gone down to the merchants and found nothing for barter. Now the scribe lands on the shore. He surveys the harvest. Attendant are behind him with staffs, Nubians with clubs. One says [to him]: "Give grain." "There is none." He is beaten savagely. He is bound, thrown in the well, submerged head down. His wife is bound in his presence. His children are in fetters. His neighbors abandon them and flee. When it is over, there is no grain.

“If you have any sense, be a scribe. If you have learned about the peasant, you will not be able to be one. Take note of it!.... Furthermore. Look, I instruct you to make you sound; to make you hold the palette freely. To make you become one whom the king trusts; to make you gain entrance to treasury and granary. To make you receive the ship-load at the gate of the granary. To make you issue the offerings on feast days. You are dressed in fine clothes; you own horses. Your boat is on the river; you are supplied with attendants. You stride about inspecting. A mansion is built in your town. You have a powerful office, given you by the king. Male and female slaves are about you. Those who are in the fields grasp your hand, on plots that you have made. Look, I make you into a staff of life! Put the writings in your heart, and you will be protected from all kinds of toil. You will become a worthy official.

“Do you not recall the [fate of] the unskilled man? His name is not known. He is ever burdened [like an ass carrying things] in front of the scribe who knows what he is about. Come, [let me tell] you the woes of the soldier, and how many are his superiors: the general, the troop-commander, the officer who leads, the standard-bearer, the lieutenant, the scribe, the commander of fifty, and the garrison-captain. They go in and out in the halls of the palace, saying: "Get laborers!" He is awakened at any hour. One is after him as [after] a donkey. He toils until the Aten sets in his darkness of night. He is hungry, his belly hurts; he is dead while yet alive. When he receives the grain-ration, having been released from duty, it is not good for grinding.

“He is called up for Syria. He may not rest. There are no clothes, no sandals. The weapons of war are assembled at the fortress of Sile. His march is uphill through mountains. He drinks water every third day; it is smelly and tastes of salt. His body is ravaged by illness. The enemy comes, surrounds him with missiles, and life recedes from him. He is told: "Quick, forward, valiant soldier! Win for yourself a good name!" He does not know what he is about. His body is weak, his legs fail him. When victory is won, the captives are handed over to his majesty, to be taken to Egypt. The foreign women faints on the march; she hangs herself [on] the soldier's neck. His knapsack drops, another grabs it while he is burdened with the woman. His wife and children are in their village; he dies and does not reach it. If he comes out alive, he is worn out from marching. Be he at large, be he detained, the soldier suffers. If he leaps and joins the deserters, all his people are imprisoned. He dies on the edge of the desert, and there is none to perpetuate his name. He suffers in death as in life. A big sack is brought for him; he does not know his resting place.

“Be a scribe, and be spared from soldiering! You call and one says: "Here I am." You are safe from torments. Every man seeks to raise himself up. Take note of it! Furthermore. [To] the royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen-Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht. The scribe Wenemdiamun greets his lord: In life, prosperity, and health! This letter is to inform my lord. Another message to my lord. I grew into a youth at your side. You beat my back; your teaching entered my ear. I am like a pawning horse. Sleep does not enter my heart by day; nor is it upon me at night. [For I say:] I will serve my lord just as a slave serves his master.

“I shall build a new mansion for you [on] the ground of your town, with trees [planted] on all its sides. There are stables within it. Its barns are full of barley and emmer, wheat, cumin, dates, ...beans, lentils, coriander, peas, seed-grain, ...flax, herbs, reeds, rushes, ...dung for the winter, alfa grass, reeds, ...grass, produced by the basketful. Your herds abound in draft animals, your cows are pregnant. I will make for you five aruras of cucumber beds to the south.”

Tomb of Wah; What It Says About the Life of a Scribe

granary scribes

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Just over 4,000 years ago, in about 2005 B.C., a boy named Wah was born in the Upper Egyptian province of Waset, which took its name from the city better known today by its ancient Greek name—Thebes. At that time, Thebes was the capital of all Egypt, and Nebhepetre Mentuhotep, founder of the Middle Kingdom, was nearing the end of his long reign. Nebhepetre was a member of the Theban family that had controlled a large part of Upper Egypt for several generations. Early in the third decade of his reign, about twenty-five years before Wah's birth, the king reunited Upper and Lower Egypt after a period of civil war and took the Horus name Sematawy—Uniter of the Two Lands. For his accomplishment, Nebhepetre was forever honored by the Egyptians as one of their greatest pharaohs. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“While growing up, Wah undoubtedly heard tales of the difficult time when there had been no supreme leader ruling over the two lands of Egypt, and Thebes was cut off from trade with the foreign lands to the northeast. He must have been told countless times of the heroic deeds of Nebhepetre and his supporters, who had fought to reunite the Nile valley in the south with the delta in the north. But in Wah's lifetime there was peace, and prosperity was returning to the land. \^/

“Early in his life, probably when he was six or seven, Wah began studying to become a scribe . Learning the art of writing was a long, painstaking process, accomplished primarily by copying standard religious texts, famous literary works, songs, and poetry. Wah may have mastered both formal hieroglyphic and the cursive hieratic scripts, memorizing hundreds of signs and learning which had specific meanings in themselves; which represented sounds and could be used to spell out words; which were determinatives, or signs that give clues as to the meaning of a word; and which could be used in more than one of these ways. He would have practiced forming signs , learning their correct size and spacing in relation to one another. He would also have learned to mix ink and to make brushes from reeds, for Egyptian handwriting was a form of painting, and the finest scribes developed personal hands that were calligraphic in style. \^/

“Sometime in his youth, perhaps quite early in his scribal training, Wah went to work on the estate of Meketre, a wealthy Theban who had begun his career as a government official during the reign of Nebhepetre and eventually rose to the exalted position of "seal bearer," or treasurer—one of the most powerful positions at court. A man of Meketre's importance probably owned a great deal of land, and his private domain would have been virtually self-sufficient, with tenant farmers, artisans and other specialized laborers, scribes, administrators, and servants all living and working on the estate. Wah probably began his service as one of the lower-level scribes, keeping accounts and writing letters. Ultimately, he became an overseer, or manager, of the storerooms on the estate. \^/

“We can speculate about some of Wah's duties thanks to a set of wooden models that were probably made during his lifetime as part of the burial equipment of his employer, Meketre. These small scenes, which form one of the finest and most complete sets of Middle Kingdom funerary models ever discovered, can be interpreted on more than one level. All of them have symbolic meanings connected with Egyptian funerary beliefs, but they also provide a picture of the day-to-day tasks that were performed on an ancient Egyptian estate. The basis of Egypt's economy was agriculture, and the grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables raised on Meketre's lands would have been his most important assets. A large portion of the crops would have been dried or processed into oil and wine, stored, and used throughout the year in the estate's kitchens . Some of the produce was set aside for taxes and salaries. Anything left over could be traded for raw materials or luxury items not available on the estate. \^/

“Artisans on the estate produced ceramic vessels in which to store beer and wine; carpenters made and repaired furniture, doors, windows, and perhaps even coffins and other funerary equipment, when necessary; weavers wove the hundreds of yards of linen used in every aspect of life and for wrapping mummies after death. In his adult years, Wah probably oversaw the output of all of the artisanal shops, as well as the storage of agricultural produce, the paying of taxes, and the doling out of wages in grain, cloth, and other products for work done on the estate. \^/

“As a young man, Wah must have been an imposing individual; at nearly six feet, his height far exceeded that of most of his contemporaries. However, at some point he seems to have injured both of his feet, and his duties as a scribe and overseer probably allowed him to maintain quite a sedentary lifestyle. Perhaps as a result of these circumstances, by his mid-twenties Wah had become obese—a sign of great prosperity, but also perhaps of poor health, for he died before he was thirty. \^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018