LABOR IN ANCIENT EGYPT

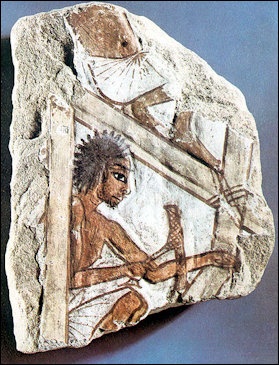

Egyptian carpenter

As agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen.

Organized labor was also needed to build other structures, quarry stone, mine precious metals and stones and build and maintain irrigation canals and other water projects. The Egyptians built many canals and irrigations systems. They didn’t make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them.

Among those that worked in trades and professions in ancient Egyptian were: barbers, potters, arrow makers, merchants, basket makers, record keepers, tool and weapons makers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, butchers, stonemasons, water carriers, fishermen, estate workers, farmers, tanners, weavers, boatbuilders, furniture makers, bakers, metal workers, pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers and jewelers.

Many craftsmen and artisans were employed by the state and nobles. Their shops and workshops were often set up near the palaces of the pharaohs, aristocrats or high officials. Their crafts tended to be passed on from one generation to the next

Being a scribe was considered a good job. Dr. Carol R. Fontaine, an assistant professor of Old Testament at the Andover Newton Theological School in Massachusetts, told the New York Times, that, according to papyri that have been translated, the scribes regarded writing as a good way to make a living, much better than being potterymakers (who were ''smeared with soil, like one whose relations have died''), merchants (who spent all their time in river travel), watchmen (who suffered bad hours), shoemakers (who forever had ''red hands'') and soldiers (who drank bad water, marched up hills a lot and ran the risk of getting killed). See Scribes Under People and Life, Language

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Egyptian History (32 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Religion (24 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Life and Culture (36 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Government, Infrastructure and Economics (24 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Ancient Egypt Magazine ancientegyptmagazine.co.uk; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Egyptian Study Society, Denver egyptianstudysociety.com; The Ancient Egypt Site ancient-egypt.org; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Work in Ancient Egypt

As agriculture became more advanced, surpluses were generated, freeing farmers to perform other jobs. Over time former farmers could earn enough to specialize in certain tasks and become what would qualify as craftsmen. Organized labor was also needed to build other structures, quarry stone, mine precious metals and stones and build and maintain irrigation canals and other water projects. The Egyptians built many canals and irrigations systems. They didn't make so many roads. Roads were not so important because they relied on the Nile for transportation. The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them.

grinding grain

For much of the year it seems that most people in ancient Egypt were involved in agricultural activity of some kind, but during the flood (July-October) the workforce was used by the state to do things like build pyramids and monuments or engage in major projects such as "rehabilitation" of the land following the recession of the flood. This involved re-establishing property boundaries and maintaining the irrigation system through work such recutting canals and rebuilding dykes.” [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

According to the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: “During and after the annual flood of the Nile, the population were subject to compulsory labour on state projects such as building and maintenance of the irrigation system. In life it would be possible to avoid this by providing a substitute; in death, mummiform figurines or "Answerers" could serve the same purpose. The Egyptian words for these statuettes (usually called shabtis in English), are ushabti and shawabti. These words are of uncertain origin but may have been derived from the Egyptian word wSb(1) meaning "answer." [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

In ancient Egypt there was paid labor (usually through rations), corvée compulsory labor and slavery. In addition there were farmers, at least some of whom were also workers during the season when there was not much agricultural work to do. Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “An income strategy different from subsistence was labor, either voluntary or compulsory. Compulsory labor is known from ancient Egypt in two forms: corvée and slavery. Corvée (bH) is well attested as periodical compulsory labor (especially in earlier periods), and everyone but the highest functionaries could be subjected to it. In the Old Kingdom, groups of workers subject to this practice were called mrt and worked in agricultural domains founded by the government . The same word mrt was used for the personnel of temple workshops in the New Kingdom; these were often prisoners taken during military campaigns. In the Middle Kingdom, temporary compulsory labor on state fields was controlled by the xnrt (interpreted as "labor camp" by Quirke). Even the nmH(y) of the New Kingdom (see Institutional and Private Interests above) could be summoned for service to government officials, as becomes clear from the decree of King Horemheb.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Among those that worked in trades and professions in ancient Egyptian were: barbers, potters, arrow makers, merchants, basket makers, record keepers, tool and weapons makers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, butchers, stonemasons, water carriers, fishermen, estate workers, farmers, tanners, weavers, boatbuilders, furniture makers, bakers, metal workers, pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers and jewelers. Many craftsmen and artisans were employed by the state and nobles. Their shops and workshops were often set up near the palaces of the pharaohs, aristocrats or high officials. Their crafts tended to be passed on from one generation to the next

Satire of the Trades

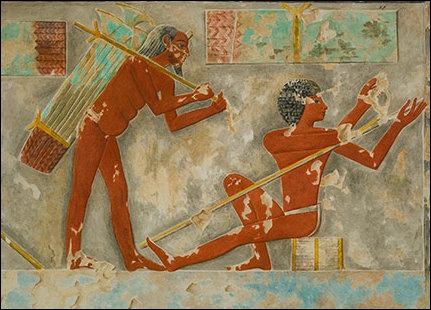

men splitting papyrus

A text called “The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety”from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) offers a scribe’s unflattering view of various jobs. It goes: “I do not see a stoneworker on an important errand or a goldsmith in a place to which he has been sent, but I have seen a coppersmith at his work at the door of his furnace. His fingers were like the claws of the crocodile, and he stank more than fish excrement. [Adolf Erman, “The literature of the ancient Egyptians; poems, narratives, and manuals of instruction, from the third and second millennia B. C.,” 1927, London, Methuen & co. ltd., pp. 67f. reshafim.org]

“Every carpenter who bears the adze is wearier than a fieldhand. His field is his wood, his hoe is the axe. There is no end to his work, and he must labor excessively in his activity. At nighttime he still must light his lamp. The jeweler pierces stone in stringing beads in all kinds of hard stone. When he has completed the inlaying of the eye-amulets, his strength vanishes and he is tired out. He sits until the arrival of the sun, his knees and his back bent at (the place called) Aku-Re. The barber shaves until the end of the evening. But he must be up early, crying out, his bowl upon his arm. He takes himself from street to street to seek out someone to shave. He wears out his arms to fill his belly, like bees who eat (only) according to their work.

“The reed-cutter goes downstream to the Delta to fetch himself arrows. He must work excessively in his activity. When the gnats sting him and the sand fleas bite him as well, then he is judged. The potter is covered with earth, although his lifetime is still among the living. He burrows in the field more than swine to bake his cooking vessels. His clothes being stiff with mud, his head cloth consists only of rags, so that the air which comes forth from his burning furnace enters his nose. He operates a pestle with his feet with which he himself is pounded, penetrating the courtyard of every house and driving earth into every open place.

“I shall also describe to you the bricklayer. His kidneys are painful. When he must be outside in the wind, he lays bricks without a garment. His belt is a cord for his back, a string for his buttocks. His strength has vanished through fatigue and stiffness, kneading all his excrement. He eats bread with his fingers, although he washes himself but once a day.

“It is miserable for the carpenter when he planes the roof-beam. It is the roof of a chamber 10 by 6 cubits. A month goes by in laying the beams and spreading the matting. All the work is accomplished. But as for the food which is to be given to his household (while he is away), there is no one who provides for his children.”

More Jobs from “Satire of the Trades”

pottery maker

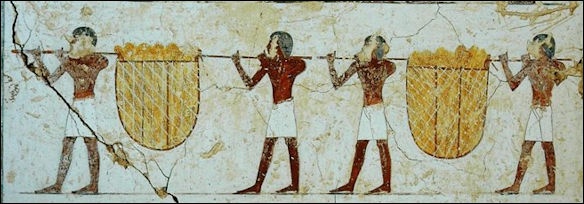

“The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety” from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) continues: “The vintner carries his shoulder-yoke. Each of his shoulders is burdened with age. A swelling is on his neck, and it festers. He spends the morning in watering leeks and the evening with corianders, after he has spent the midday in the palm grove. So it happens that he sinks down (at last) and dies through his deliveries, more than one of any other profession.

“The fieldhand cries out more than the guinea fowl. His voice is louder than the raven's. His fingers have become ulcerous with an excess of stench. When he is taken away to be enrolled in Delta labour, he is in tatters. He suffers when he proceeds to the island, and sickness is his payment. The forced labour then is tripled. If he comes back from the marshes there, he reaches his house worn out, for the forced labor has ruined him.

“The weaver inside the weaving house is more wretched than a woman. His knees are drawn up against his belly. He cannot breathe the air. If he wastes a single day without weaving, he is beaten with 50 whip lashes. He has to give food to the doorkeeper to allow him to come out to the daylight. The arrow maker, completely wretched, goes into the desert. Greater than his own pay is what he has to spend for his she-ass for its work afterwards. Great is also what he has to give to the fieldhand to set him on the right road to the flint source. When he reaches his house in the evening, the journey has ruined him.

“The courier goes abroad after handing over his property to his children, being fearful of the lions and the Asiatics. He only knows himself when he is back in Egypt. But his household by then is only a tent. There is no happy homecoming. The furnace-tender, his fingers are foul, the smell thereof is as corpses. His eyes are inflamed because of the heaviness of smoke. He cannot get rid of his dirt, although he spends the day at the reed pond. Clothes are an abomination to him. The sandal maker is utterly wretched carrying his tubs of oil. His stores are provided with carcasses, and what he bites is hides.

“The washerman launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile. I shall go away, father, from the flowing water, said his son and his daughter, to a more satisfactory profession, one more distinguished than any other profession. His food is mixed with filth, and there is no part of him which is clean. He cleans the clothes of a woman in menstruation. He weeps when he spends all day with a beating stick and a stone there. One says to him, dirty laundry, come to me, the brim overflows.

“The fowler is utterly weak while searching out for the denizens of the sky. If the flock passes by above him, then he says: would that I might have nets. But God will not let this come to pass for him, for He is opposed to his activity. I mention for you also the fisherman. He is more miserable than one of any other profession, one who is at his work in a river infested with crocodiles. When the totalling of his account is made for him, then he will lament. One did not tell him that a crocodile was standing there, and fear has now blinded him. When he comes to the flowing water, so he falls as through the might of God.”

Activities and Occupations in Ancient Egyptian Villages

hunter

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Leaving aside such “institutional” communities as Deir el-Medina or the pyramid towns, which relied directly on the Pharaonic administration, agriculture and herding were the main productive activities of Egyptian villages. It is probable that fishing and extensive herding led to the development of specific kinds of settlements and temporary encampments in particularly favored areas like the Fayum or the Delta. The 8th Dynasty inscription of Henqu of Deir el-Gabrawi, for instance, opposes two kinds of landscape, one formerly inhabited by fowlers, fishermen, and extensive herders, but subsequently settled by people and provided with flocks . The Gebelein papyri, from the end of the 4th Dynasty, contain a detailed list of the (presumable) heads of the households of several localities. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Many villagers were Hm nswt, “serf of the king,” or jst, “member of a team of workers,” and were probably peasants, but others were involved in activities such as herding, hunting, collecting honey, or fishing, and even some Hrj-Sa, “nomad”, are cited. Moreover, other people worked as millers and ship’s carpenters, whereas the scribes and agents of the crown must have formed the local elite alongside the chiefs of the villages. Thus, these documents provide an invaluable glimpse into the occupations and economic activities of some villages. Commercial activities are rarely documented, but marketplaces put the villagers in contact with other producers, traders, and institutions. Several New Kingdom papyri record ships in the service of temples, which collected goods from many localities, and some data suggest that private trade was also conducted during these journeys. It is possible that the growing importance of dmj(t) (“town, village,” but formerly “moorings, port”) in New Kingdom sources might be related to the growing importance of trade and river connections in the organization of the landscape. Finally, the tomb robbery papyri of the late New Kingdom reveal that private trade linked villagers and merchants, with precious metals fuelling non-institutional economic circuits where gold and silver were exchanged for plots of land, animals, and goods.

“Differences in wealth were obviously mirrored in the economy of villagers. Thus, for instance, yokes and ploughs, and probably donkeys too, were only accessible to rich peasants, whereas common villagers seem to have practiced intensive horticulture in small gardens. Archaeozoological research is providing increasing evidence of the importance of small-scale animal husbandry (pigs, sheep, and goats) in humble domestic contexts, and fish appears to have been an important component of poor people’s diets, sometimes imported from distant places thanks to private commercial circuits. Regional patterns of production and processing of food (i.e., barley at Abydos as opposed to emmer in Giza and Memphis), seasonal activities, the importance of fodder provision, the social patterns of differentiated consumption, etc. reveal a village economy less static and rather more complex than previously assumed, which was also subject to changes over time. Consequently, social hierarchy and wealth inequalities were reinforced by the risks inherent to agriculture as well as by indebtedness or heritage divisions, thus fostering clientelism and servitude and reinforcing the power of local leaders whose status was further enhanced by their connections with temples, regional potentates, and the agents of the crown.

Paid Labor Versus Corvee Labor in Ancient Egypt

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Textual sources apparently concerned with wage labor actually refer to institutional workforces who were given rations. Rations could, however, could be so high as to enable the receiving institutional craftsmen to trade with their grain surplus. The same craftsmen could use their expertise to produce items for the market in their spare time in order to obtain additional income. There are no indications of the existence of a free labor market for craftsmen or other specialized workers. It is unlikely, however, that craftsmanship was only institutional: archaeological and ethnological research suggests industry, seasonal or permanent, in peasant households and local workshops.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Little is known about the payment of urban workers, employed in either private or public constructions, in the form of wages rather than in the context of compulsory work (corvée labor). However, many inscriptions from the Old Kingdom do refer to officials who built their tombs with their own means and who remunerated the craftsmen and builders involved with copper and cloth, as well as grain and beer. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Thus, apparently, craftmen could be paid on a private basis and their skills put occasionally at the service of customers rather than institutional workshops. The huge New Kingdom construction projects at Pi-Ramesse, Karnak, and elsewhere, or the temples built in the first millennium BCE, likely mobilized a considerable combined mass of skilled workers, farmers engaged in unskilled work on a seasonal basis, craftspeople, and workers in charge of transport activities, etc., engaged on a “contractual” basis (not as corvée) and paid with wages (in some cases by private patrons).

“Indeed, demand for the latter individuals might have stimulated urban markets —for instance, the production of fresh vegetables in artificially irrigated gardens. In sharp contrast, the bulk of information at our disposal about people living in cities refers to scribes, administrators, priests, members of the court, military personnel, and agents of the crown.”

Corvee Labor in the Middle Kingdom

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “The collapse of the Old Kingdom was followed by the tumultuous First Intermediate Period during which the equilibrium between the central authority and powerful provincial interests broke down. The pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom were able to stabilize the central government. From the Middle Kingdom comes detailed documentation of punishments inflicted on peasants who sought to avoid the corvée and thereby deny the state its right to their occasional labor tilling fields, maintaining irrigation channels, working on construction projects, or obtaining raw materials abroad. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University of Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Papyrus Brooklyn 35.1446 describes the situation of eighty inhabitants of Upper Egypt who fled their national service obligations in the reign of Amenemhat III and were subsequently sentenced to indefinite terms of compulsory labor on government xbsw lands, their families imprisoned until their return. The agricultural labor referred to in this text is perhaps better described as conscription to forced tenancy on land undergoing development or redevelopment than what is commonly understood by the term “corvée labor”.

“Such conscription was a form of taxation by the state imposed upon all Egyptians below the rank of official, including priests and, most importantly, unskilled laborers from a huge labor pool at the bottom of Egyptian society, largely consisting of peasants tied to the land they worked, irrespective of its ownership. The burden of such forced agricultural labor for the vast majority of Egyptian laborers was not only inescapable but often unfairly and ruthlessly applied despite pleas to the authorities from persons unjustly seized. It is difficult to see how such persons would have benefited from a redistributive tax system, with the possible exception of those peasant farmers toiling upon the estates of temples exempted from the corvée by royal charter.

Worker’s Village of Amarna

Deir el-Medina

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The village is one of few housing areas at Amarna to have been formally planned: it is laid out with rows of 73 equally sized house plots, and one larger house, all surrounded by a perimeter wall around 80 centimeters thick with two entranceways. Apart from the larger house, thought to belong to an overseer, the village houses exhibit at ground-floor level a tripartite plan not generally found in the riverside suburbs, with a staircase leading to a roof or further s tory/s above . Perhaps quite soon after the village was founded, its occupants modified and added to their houses and settled the land outside the village walls, constructing chapels, tombs, animal pens, and garden plots. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The latter reflect the efforts of the villagers themselves to sustain their community, but the isolated location of the site, and lack of a well, also made it dependent on supplies from outside. An area of jar stands known as the Zir Area on the route into the village seems to represent the standing stock of water for the village, supplied by deliveries from the riverside city, the route of which is still marked by a spread of broken pottery vessels (Site X2). Near the end of the sherd trail there is a small building (Site X1), which may be a checkpoint connected with the importation of commodities.

“Given its location and similarity to the tomb workers’ village at Deir el-Medina, the Workmen’s Village is thought to have housed workers, and their families, who cut and decorated the rock-cut tombs, including those in the Royal Wadi. This identification is supported by the discovery at the site of a statue base mentioning a “Servant in the Place,” recalling the name “Place of Truth ” used by the tomb-cutters at Deir el-Medina.

“The internal history of the village, however, is not easy to reconstruct. At some stage an extension was added to the walled settlement, possibly to accommodate a growing workforce to help complete the royal tombs. It has also been suggested that, perhaps late in its occupation, the site housed a policing unit. Excavations have produced a relatively high proportion of jar labels and faience jewelry from the last years of the reign of Akhenaten and those of his successors, suggesting a burgeoning of activity at this time, but without ruling out earli er occupation. The discovery of a 19 th Dynasty coffin beside the Main Chapel indicates that the village site was still known of later in the New Kingdom.”

Substitute Workers in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Interestingly, Old Kingdom lists of personnel frequently state that workers were actually replaced by their wives, fathers, brothers, sons, or daughters, or by other persons. Middle Kingdom papyri from Lahun confirm this practice: in one case the names of several workers were accompanied by annotations specifying that they should be brought in person or replaced by their wives, mothers, or Asiatics (serfs?) ; in another case, a governor requested two workers or, in their place, men or women from among their own dependants; finally, another papyrus not only listed a labor force but also identified the persons (usually priests and officials) for whom the worker answered the call. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“Sometimes, workers recruited on a local basis came from the households (pr) and districts (rmny) of provincial potentates. New Kingdom sources also mention tenants acting as agents of scribes . At a higher social level, clients or colleagues were expected to replace their “patrons” when performing ritual services in the temples. In exchange for their services, the superior was expected to take care of his subjects. Such bonds linking clients and subordinates to their patron’s household were significantly marked by the use of kinship terms.

“Thus, compulsory workers were sometimes described as the “sons” of prominent citizens: “N, he is called the son of Senbebu, a priest of Thinis,” “N, he is called the son of Hepu, a commander of soldiers [of This]” (Hayes 1955: 25 - 26), while palatial officials were explicitly labeled as “friends” (xnms.f) or “(pseudo-)children” (Xrd.f) of their superior. More clearly, the patron-client relationship was sometimes formalized by means of legal contracts, even by fictitious adoptions that masked what constituted, in fact, the voluntary servitude of the person called Srj “son”. Lastly, vertical integration often implied that someone was the client or subordinate of another person who, in turn, proved to be the client of a third individual.

Apprenticeship in Ancient Egypt

Nikolaos Lazaridis of the Centre for Research in Information Management wrote: “In contrast to “education,” whose conventional definition, in the case of this essay, covers aspects of basic training received at school, “apprenticeship” is a term that usually refers to a specific method of instruction, namely the instruction offered by a single teacher to a single or a small number of students on one or more specialized subjects or skills. This was a very popular educational method that was employed mainly when advanced training was sought out in order to develop some of the aspects of the curricula of Egyptian schools, such as writing or mathematics, or to introduce new subjects and skills, such as the study of religious texts or the learning of a craft. In addition, apprenticeship was a manner of instruction that was probably also used in some local Egyptian schools even for basic training— perhaps due to the small number of teachers and students available. [Source: Nikolaos Lazaridis, Centre for Research in Information Management, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The term most probably denoting apprenticeship read Xrj-a, which literally meant “under the arm/control of,” while the expertteacher was called either nb, “master,” or jtj, “father.” The latter is a term employed mainly in literary contexts to imply a close father-son relationship for that between an instructor and his audience. Thus, for instance, the title “father” is often used in didactic texts, denoting the author of the instruction and teacher of an audience that has still much to learn: ‘Beginning of the sayings of excellent discourse spoken by the Prince….Ptahhotep, in instructing the ignorant to understand and be up to the standard of excellent discourse…So he spoke to his son.’ [Instruction of Ptahhotep]”

On the issue of sources regarding apprenticeships “in ancient Egypt, the available evidence concerns mainly the training of draftsmen and consists of: a) practice ostraca, and b) textual references to artisan training. As with school exercises, practice material can be identified as such due to their crude drawings and the fact that they were painted on ostraca...In contrast to the considerable amount of evidence available for basic school education in ancient Egypt, there is much less evidence for apprenticeship in advanced or special subjects and skills. Such evidence includes, for example, painted ostraca from Deir el-Medina that could have been made by artisan apprentices in situ. Probable references to such young apprentices are made in other ostraca from Deir el-Medina. Finally, there is also some evidence of the manner in which temple musicians were trained. Overall, the method of knowledge transfer through apprenticeship in Pharaonic Egypt was most likely informal and circumstantial, based not so much upon a uniform curriculum but rather upon the personal choices of the experienced professional who took over the education of his potential successors. The close relationship between artisan apprenticeship and school education is evident in the case of a number of tombs, in the context of which school exercises have been discovered. This evidence might indicate that Egyptian students were learning how to read and write by using the material inscribed on tomb walls. After all, tombs in ancient Egypt probably also functioned as places where important works of literature were meant to be preserved. In such cases, the artisan master who was overseeing the works in tombs would probably have also acted more broadly as a teacher.”

Workers on the Move in Ancient Egypt

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “Apart from members of expeditions and of the army, other travelers with a variety of occupations are mentioned in the texts. Egyptian physicians not only took part in expeditions, but they were sent out by the pharaoh on building projects and to foreign royal courts, due to the considerable repute they enjoyed. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Architects were on the move for professional reasons and on behalf of the pharaoh to supervise official building projects. One such architect was Nekhebu of the 6th Dynasty. He was sent out several times by Pepy I to Upper and Lower Egypt to oversee the digging of a canal in Qus and the royal building projects in Heliopolis, where he stayed for six years. During this time, he made a few official trips to the residence in Memphis.

“The mobility of scribes arose from the fact that, being part of the bureaucracy, they were transferred by official order to new places of employment as required. This could be sent within Egypt but abroad as well. Such a widely traveled scribe was Nebnetjeru, whose graffiti is found between Kalabsha and Dendur, near Tonkalah, and possibly even at Toshka.

“Craftsmen were also on the move. There is evidence of craftsmen in the service of private individuals and of pharaoh. They were not necessarily tied to a particular workshop but were sent out on expeditions and large-scale royal building projects. Even higher-ranking craftsmen with titles such as Hmw wr, jmj-rA kAt, and jmj-rA nbjw n pr Ra are among those whose project-related work orders caused them to travel.

“Priests traveled not only as members of expeditions but also in order to fulfil special duties for temples or to organize religious festivities, as did Ikhernofret at Abydos in the 12th Dynasty. A high official’s occupational move to a different location is frequently mentioned. Mayors , viziers, as well as the pharaoh traveled on official government business—e.g., inspections, and diplomatic or military missions. Royal journeys are shown to have taken place beginning in Predynastic times from several sources including annals. Furthermore, the so-called Smsw 1rw, the “following of Horus,” took place every two years and led the king through the whole land . In the New Kingdom, Pharaoh traveled yearly for religious reasons to Thebes to celebrate the Opet Festival. Royal travels are further attested in the annals of Thutmose III reporting his war campaigns or the inscriptions at the temple of Kanais recording a visit by Sety I to the Eastern Desert.”

Scribe: A Good Job in Ancient Egypt

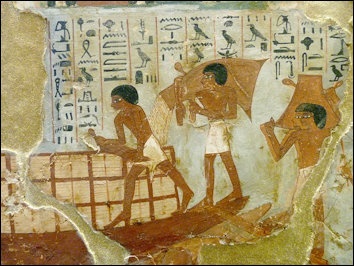

granary scribes

Being a scribe was considered a good job. Dr. Carol R. Fontaine, an assistant professor of Old Testament at the Andover Newton Theological School in Massachusetts, told the New York Times, that, according to papyri that have been translated, the scribes regarded writing as a good way to make a living, much better than being potterymakers (who were ''smeared with soil, like one whose relations have died''), merchants (who spent all their time in river travel), watchmen (who suffered bad hours), shoemakers (who forever had ''red hands'') and soldiers (who drank bad water, marched up hills a lot and ran the risk of getting killed). See Scribes Under People and Life, Language

Ancient Egypt writing-and also reading-was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.

“One final position within the priesthood highly worthy of mention is that of the Scribes. The scribes were highly prized by both the pharaoh and the priesthood, so much so that in some of the pharaoh's tombs, the pharaoh himself is depicted as a scribe in pictographs. The scribes were in charge of writing magical texts, issuing royal decrees, keeping and recording the funerary rites (specifically within The Book of The Dead) and keeping records vital to the bureaucracy of Ancient Egypt. The scribes often spent years working on the craft of making hieroglyphics, and deserve mentioning within the priestly caste as it was considered the highest of honors to be a scribe in any Egyptian court or temple. +\ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Instruction Letter to Egyptian Scribes

Beginning of the instruction in letter-writing made by the royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen-Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht for his apprentice, the scribe Wenemdiamun: “[The royal scribe] and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen- [Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht speaks to the scribe Wenemdiamun]. [Apply yourself to this] noble profession.... Your will find it useful.... You will be advanced by your superiors. You will be sent on a mission.... Love writing, shun dancing; then you become a worthy official. Do not long for the marsh thicket. Turn your back on throw-stick and chase. By day write with your fingers; recite by night. Befriend the scroll, the palette. It pleases more than wine. Writing for him who knows it is better than all other professions. It pleases more than bread and beer, more than clothing and ointment. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the west. [Source: Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), I, pp. 168-173.

“Young fellow, how conceited you are! You do not listen when I speak. Your heart is denser than a great obelisk, a hundred cubits high, ten cubits thick. When it is finished and ready for loading, many work gangs draw it. It hears the words of men; it is loaded on a barge. Departing from Yebu it is conveyed, until it comes to rest on its place in Thebes. So also a cow is bought this year, and it plows the following year. It learns to listen to the herdsman; it only lacks words. Horses brought from the field, they forget their mothers, Yoked they go up and down on all his majesty's errands. They become like those that bore them, that stand in the stable. They do their utmost for fear of a beating. But though I beat you with every kind of stick, you do not listen. If I knew another way of doing it, I would do it for you, that you might listen. You are a person fit for writing, though you have not yet known a woman. Your heart discerns, your fingers are skilled, your mouth is apt for reciting.

scribe stuff

“Writing is more enjoyable than enjoying a basket of [?] and beans; more enjoyable that a mother's giving birth, when her heart knows no distaste. She is constant in nursing her son; her breast is in his mouth every day. Happy is the heart [of] him who writes; he is young each day. The royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen- Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht, speaks to the scribe Wenemdiamun, as follows. You are busy coming and going, and do not think of writing. You resist listening to me; you neglect my teachings.

“You are worse than the goose of the shore that is busy with mischief. It spends the summer destroying the dates, the winter destroying the seed-grain. It spends the balance of the year in pursuit of the cultivators. It does not let seed be cast to the ground without snatching it.... One cannot catch it by snaring. One does not offer it in the temple. The evil, shape-eyed bird that does no work! You are worse than the desert antelope that lives by running. It spends no day in plowing. Never at all does it tread on the threshing-floor. It lives on the oxen's labor, without entering among them. But though I spend the day telling you "Write," it seems like a plague to you. Writing is very pleasant!....

“See for yourself with your own eye. The occupations lie before you. The washerman's day is going up, going down. All his limbs are weak, [from] whitening his neighbor's clothes every day, from washing their linen. The maker of pots is smeared with soil, like one whose relations have died. His hands, his feet are full of clay; he is like one who lives in the bog. The cobbler mingles with vats. His odor is penetrating. His hands are red with madder, like one who is smeared with blood. He looks behind him for the kite, like one whose flesh is exposed. The watchman prepares garlands and polishes vase-stands. He spends a night of toil just as one on whom the sun shines.

“The merchants travel downstream and upstream. They are as busy as can be, carrying goods from one town to another. They supply him who has wants. But the tax collectors carry off the gold, that most precious of metals. The ships' crews from every house [of commerce], they receive their loads. They depart from Egypt for Syria, and each man's god is with him. [But] not one of them says: "We shall see Egypt again!" The carpenter who is in the shipyard carries the timber and stacks it. If he gives today the output of yesterday, woe to his limbs! The shipwright stands behind him to tell him evil things. His outworker who is in the fields, his is the toughest of all the jobs. He spends the day loaded with his tools, tied to his toolbox. When he returns home at night, he is loaded with the toolbox and the timbers, his drinking mug, and his whetstones.

“The scribe, he alone, records the output of all of them. Take note of it! Let me also expound to you the situation of the peasant, that other tough occupation. [Comes] the inundation and soaks him..., he attends to his equipment. By day he cuts his farming tools; by night he twists rope. Even his midday hour he spends on farm labor. He equips himself to go to the field as if he were a warrior. The dried field lies before him; he goes out to get his team. When he has been after the herdsman for many days, he gets his team and comes back with it. He makes for it a place in the field. Comes dawn, he goes to make a start and does not find it in its place. He spends three days searching for it; he finds it in the bog. He finds no hides on them; the jackals have chewed them. He comes out, his garment in his hand, to beg for himself a team.

“When he reaches his field he finds [it?] broken up. He spends time cultivating, and the snake is after him. It finishes off the seed as it is cast to the ground. He does not see a green blade. He does three plowings with borrowed grain. His wife has gone down to the merchants and found nothing for barter. Now the scribe lands on the shore. He surveys the harvest. Attendant are behind him with staffs, Nubians with clubs. One says [to him]: "Give grain." "There is none." He is beaten savagely. He is bound, thrown in the well, submerged head down. His wife is bound in his presence. His children are in fetters. His neighbors abandon them and flee. When it is over, there is no grain.

“If you have any sense, be a scribe. If you have learned about the peasant, you will not be able to be one. Take note of it!.... Furthermore. Look, I instruct you to make you sound; to make you hold the palette freely. To make you become one whom the king trusts; to make you gain entrance to treasury and granary. To make you receive the ship-load at the gate of the granary. To make you issue the offerings on feast days. You are dressed in fine clothes; you own horses. Your boat is on the river; you are supplied with attendants. You stride about inspecting. A mansion is built in your town. You have a powerful office, given you by the king. Male and female slaves are about you. Those who are in the fields grasp your hand, on plots that you have made. Look, I make you into a staff of life! Put the writings in your heart, and you will be protected from all kinds of toil. You will become a worthy official.

scribes working a granery

“Do you not recall the [fate of] the unskilled man? His name is not known. He is ever burdened [like an ass carrying things] in front of the scribe who knows what he is about. Come, [let me tell] you the woes of the soldier, and how many are his superiors: the general, the troop-commander, the officer who leads, the standard-bearer, the lieutenant, the scribe, the commander of fifty, and the garrison-captain. They go in and out in the halls of the palace, saying: "Get laborers!" He is awakened at any hour. One is after him as [after] a donkey. He toils until the Aten sets in his darkness of night. He is hungry, his belly hurts; he is dead while yet alive. When he receives the grain-ration, having been released from duty, it is not good for grinding.

“He is called up for Syria. He may not rest. There are no clothes, no sandals. The weapons of war are assembled at the fortress of Sile. His march is uphill through mountains. He drinks water every third day; it is smelly and tastes of salt. His body is ravaged by illness. The enemy comes, surrounds him with missiles, and life recedes from him. He is told: "Quick, forward, valiant soldier! Win for yourself a good name!" He does not know what he is about. His body is weak, his legs fail him. When victory is won, the captives are handed over to his majesty, to be taken to Egypt. The foreign women faints on the march; she hangs herself [on] the soldier's neck. His knapsack drops, another grabs it while he is burdened with the woman. His wife and children are in their village; he dies and does not reach it. If he comes out alive, he is worn out from marching. Be he at large, be he detained, the soldier suffers. If he leaps and joins the deserters, all his people are imprisoned. He dies on the edge of the desert, and there is none to perpetuate his name. He suffers in death as in life. A big sack is brought for him; he does not know his resting place.

“Be a scribe, and be spared from soldiering! You call and one says: "Here I am." You are safe from torments. Every man seeks to raise himself up. Take note of it! Furthermore. [To] the royal scribe and chief overseer of the cattle of Amen-Re, King of Gods, Nebmare-nakht. The scribe Wenemdiamun greets his lord: In life, prosperity, and health! This letter is to inform my lord. Another message to my lord. I grew into a youth at your side. You beat my back; your teaching entered my ear. I am like a pawning horse. Sleep does not enter my heart by day; nor is it upon me at night. [For I say:] I will serve my lord just as a slave serves his master.

“I shall build a new mansion for you [on] the ground of your town, with trees [planted] on all its sides. There are stables within it. Its barns are full of barley and emmer, wheat, cumin, dates, ...beans, lentils, coriander, peas, seed-grain, ...flax, herbs, reeds, rushes, ...dung for the winter, alfa grass, reeds, ...grass, produced by the basketful. Your herds abound in draft animals, your cows are pregnant. I will make for you five aruras of cucumber beds to the south.”

Tomb of Wah; What It Says About the Life of a Scribe

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Just over 4,000 years ago, in about 2005 B.C., a boy named Wah was born in the Upper Egyptian province of Waset, which took its name from the city better known today by its ancient Greek name—Thebes. At that time, Thebes was the capital of all Egypt, and Nebhepetre Mentuhotep, founder of the Middle Kingdom, was nearing the end of his long reign. Nebhepetre was a member of the Theban family that had controlled a large part of Upper Egypt for several generations. Early in the third decade of his reign, about twenty-five years before Wah's birth, the king reunited Upper and Lower Egypt after a period of civil war and took the Horus name Sematawy—Uniter of the Two Lands. For his accomplishment, Nebhepetre was forever honored by the Egyptians as one of their greatest pharaohs. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“While growing up, Wah undoubtedly heard tales of the difficult time when there had been no supreme leader ruling over the two lands of Egypt, and Thebes was cut off from trade with the foreign lands to the northeast. He must have been told countless times of the heroic deeds of Nebhepetre and his supporters, who had fought to reunite the Nile valley in the south with the delta in the north. But in Wah's lifetime there was peace, and prosperity was returning to the land. \^/

“Early in his life, probably when he was six or seven, Wah began studying to become a scribe . Learning the art of writing was a long, painstaking process, accomplished primarily by copying standard religious texts, famous literary works, songs, and poetry. Wah may have mastered both formal hieroglyphic and the cursive hieratic scripts, memorizing hundreds of signs and learning which had specific meanings in themselves; which represented sounds and could be used to spell out words; which were determinatives, or signs that give clues as to the meaning of a word; and which could be used in more than one of these ways. He would have practiced forming signs , learning their correct size and spacing in relation to one another. He would also have learned to mix ink and to make brushes from reeds, for Egyptian handwriting was a form of painting, and the finest scribes developed personal hands that were calligraphic in style. \^/

“Sometime in his youth, perhaps quite early in his scribal training, Wah went to work on the estate of Meketre, a wealthy Theban who had begun his career as a government official during the reign of Nebhepetre and eventually rose to the exalted position of "seal bearer," or treasurer—one of the most powerful positions at court. A man of Meketre's importance probably owned a great deal of land, and his private domain would have been virtually self-sufficient, with tenant farmers, artisans and other specialized laborers, scribes, administrators, and servants all living and working on the estate. Wah probably began his service as one of the lower-level scribes, keeping accounts and writing letters. Ultimately, he became an overseer, or manager, of the storerooms on the estate. \^/

“We can speculate about some of Wah's duties thanks to a set of wooden models that were probably made during his lifetime as part of the burial equipment of his employer, Meketre. These small scenes, which form one of the finest and most complete sets of Middle Kingdom funerary models ever discovered, can be interpreted on more than one level. All of them have symbolic meanings connected with Egyptian funerary beliefs, but they also provide a picture of the day-to-day tasks that were performed on an ancient Egyptian estate. The basis of Egypt's economy was agriculture, and the grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables raised on Meketre's lands would have been his most important assets. A large portion of the crops would have been dried or processed into oil and wine, stored, and used throughout the year in the estate's kitchens . Some of the produce was set aside for taxes and salaries. Anything left over could be traded for raw materials or luxury items not available on the estate. \^/

“Artisans on the estate produced ceramic vessels in which to store beer and wine; carpenters made and repaired furniture, doors, windows, and perhaps even coffins and other funerary equipment, when necessary; weavers wove the hundreds of yards of linen used in every aspect of life and for wrapping mummies after death. In his adult years, Wah probably oversaw the output of all of the artisanal shops, as well as the storage of agricultural produce, the paying of taxes, and the doling out of wages in grain, cloth, and other products for work done on the estate. \^/

“As a young man, Wah must have been an imposing individual; at nearly six feet, his height far exceeded that of most of his contemporaries. However, at some point he seems to have injured both of his feet, and his duties as a scribe and overseer probably allowed him to maintain quite a sedentary lifestyle. Perhaps as a result of these circumstances, by his mid-twenties Wah had become obese—a sign of great prosperity, but also perhaps of poor health, for he died before he was thirty. \^/

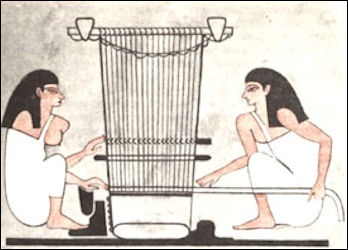

Women's Occupations in Ancient Egypt

women weaving

Career options for women were limited. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Women might find work as professional mourners--one sees a cluster of them gesturing and wailing in a funerary carving--or as performers in court and temple rituals. In a relief from the tomb of a Middle Kingdom queen, female musicians raise frondlike hands in the air as they clap out a rhythm.

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “In general, the work of the upper and middle class woman was limited to the home and the family. This was not due to an inferior legal status, but was probably a consequence of her customary role as mother and bearer of children, as well as the public role of the Egyptian husbands and sons who functioned as the executors of the mortuary cults of their deceased parents. It was the traditional role of the good son to bury his parents, support their funerary cult, to bring offerings regularly to the tombs, and to recite the offering formula. Because women are not regularly depicted doing this in Egyptian art, they probably did not often assume this role. When a man died without a surviving son to preserve his name and present offerings, then it was his brother who was often depicted in the art doing so. Perhaps because it was the males who were regularly entrusted with this important religious task, that they held the primary position in public life. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“As far as occupations go, in the textual sources upper class woman are occasionally described as holding an office, and thus they might have executed real jobs. Clearly, though, this phenomenon was more prevalent in the Old Kingdom than in later periods (perhaps due to the lower population at that time). In Wente's publication of Egyptian letters, he notes that of 353 letters known from Egypt, only 13 provide evidence of women functioning with varying degrees of administrative authority. -

“On of the most exalted administrative titles of any woman who was not a queen was held by a non-royal women named Nebet during the Sixth Dynasty, who was entitled, "Vizier, Judge and Magistrate." She was the wife of the nomarch of Coptos and grandmother of King Pepi I. However, it is possible that the title was merely honorific and granted to her posthumously. Through the length of Egyptian history, we see many titles of women which seem to reflect real administrative authority, including one woman entitled, "Second Prophet (i.e. High Priest) of Amun" at the temple of Karnak, which was, otherwise, a male office. Women could and did hold male administrative positions in Egypt. However, such cases are few, and thus appear to be the exceptions to tradition. Given the relative scarcity of such, they might reflect extraordinary individuals in unusual circumstances. -

“Women functioned as leaders, e.g., kings, dowager queens and regents, even as usurpers of rightful heirs, who were either their step-sons or nephews. We find women as nobility and landed gentry managing both large and small estates, e.g., the lady Tchat who started as overseer of a nomarch's household with a son of middling status; married the nomarch; was elevated, and her son was also raised in status. Women functioned as middle class housekeepers, servants, fieldhands, and all manner of skilled workers inside the household and in estate-workshops. -

“Women could also be national heroines in Egypt. Extraordinary cases include: Queen Ahhotep of the early Eighteenth Dynasty. She was renowned for saving Egypt during the wars of liberation against the Hyksos, and she was praised for rallying the Egyptian troops and crushing rebellion in Upper Egypt at a critical juncture of Egyptian history. In doing so, she received Egypt's highest military decoration at least three times, the Order of the Fly. Queen Hatshepsut, as a ruling king, was actually described as going on military campaign in Nubia. Eyewitness reports actually placed her on the battlefield weighing booty and receiving the homage of defeated rebels. -

Careers for Women in Ancient Egypt

dancers

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “In fact, other than housewife and mother, the most common 'career' for women was the priesthood, serving male and female deities. The title, 'God's Wife', held by royal women, also brought with it tremendous political power second only to the king, for whom they could even deputise. The royal cult also had its female priestesses, with women acting alongside men in jubilee ceremonies and, as well as earning their livings as professional mourners, they occasionally functioned as funerary priests. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Their ability to undertake certain tasks would be even further enhanced if they could read and write but, with less than 2 percent of ancient Egyptian society known to be literate, the percentage of women with these skills would be even smaller. Although it is often stated that there is no evidence for any women being able to read or write, some are shown reading documents. Literacy would also be necessary for them to undertake duties which at times included prime minister, overseer, steward and even doctor, with the lady Peseshet predating Elizabeth Garret Anderson by some 4,000 years. |::|

“By Graeco-Roman times women's literacy is relatively common, the mummy of the young woman Hermione inscribed with her profession 'teacher of Greek grammar'. A brilliant linguist herself, Cleopatra VII endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity-the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs. |::|

“With the concept that 'a woman's place is in the home' remaining largely unquestioned for the next 1,500 years, the relative freedom of ancient Egyptian women was forgotten. Yet these active, independent individuals had enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve. |::|

Ancient Egyptian Workers Got Paid Sick Leave

Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: Among the texts found at Deir el-Medina, a village of artisans near the Valley of the Kings, “are numerous daily records detailing when and why individual workmen were absent from their jobs. Nearly one-third of these absences occur when a workman was too sick to work. Yet, monthly ration distributions from Deir el-Medina are consistent enough to indicate that these workers were paid even if they were out sick for several days. [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

“These texts also identify a workman on the crew designated as the swnw, physician. The physician was given an assistant and both were allotted days off to prepare medicine and take care of colleagues. The Egyptian state even gave the physician extra rations as payment for his services to the community of Deir el-Medina. This physician would have most likely treated the workers with remedies and incantations found in his medical papyrus. About a dozen extensive medical papyri have been identified from ancient Egypt, including one set from Deir el-Medina. ***

“These texts were a kind of reference book for the ancient Egyptian medical practitioner, listing individual treatments for a variety of ailments. The longest of these, Papyrus Ebers, contains more than 800 treatments covering anything from eye problems to digestive disorders. As an example, one treatment for intestinal worms requires the physician to cook the cores of dates and colocynth, a desert plant, together in sweet beer. He then sieved the warm liquid and gave it to the patient to drink for four days. ***

“Just like today, some of these ancient Egyptian medical treatments required expensive and rare ingredients that limited who could afford to be treated, but the most frequent ingredients found in these texts tended to be common household items such as honey and grease. One text from Deir el-Medina indicates that the state rationed common ingredients to a few men in the workforce so that they could be shared among the workers. ***

“Despite paid sick leave, medical rations and a state-supported physician, it is clear that in some cases the workmen were actually laboring through their illnesses. For example, in one text, the workman Merysekhmet attempted to go to work after being sick. The text tells us that he descended to the King’s Tomb on two consecutive days, but was unable to work. He then hiked back to Deir el-Medina where he stayed for the next 10 days until he was able to work again. Although short, these hikes were steep: The trip from Deir el-Medina to the royal tomb involved an ascent greater than climbing to the top of the Great Pyramid. Merysekhmet’s movements across the Theban valleys probably were at the expense of his health. This suggests that sick days and medical care were not magnanimous gestures of the Egyptian state, but rather calculated health-care provisions designed to ensure that men like Merysekhmet were healthy enough to work.” ***

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018