PERSEPOLIS

Persepolis Persepolis (30 miles northeast of Shiraz) was the capital of the ancient Persian empire. Built by Darius the Great (522-486 B.C.) and enlarged by his immediate successors, Xerxes (486-465 B.C.) and Artaxerxes (465-424 B.C.), it was spiritual hub of the empire and one of the most glorious cities of the ancient world. Ravaged over the centuries by invaders and earthquakes, it looks a lot the ruins you see in Greece and is surrounded by barren hills.

Situated on a plateau on the slopes of Kuh-e-Rahmat, Persepolis was where the Persian kings celebrated the Persian New Year on the spring equinox, met foreign dignitaries, presided over religiosu ceremonies and were buried after the died. It was only occupied a few days a year. The kings lived with their courts at Susa to the west and Hamadan to the north. When Alexander the Great captured the city in 330 B.C. he “accidently” burnt it to the ground as an act of revenge for when the Persians burnt down Athens. The treasure of gold and jewels and other goodies he took reportedly required 30,000 mules to carry back to Greece.

Persepolis is a Greek name that means “City of Parsa” (Pasa being the Greek name for the Persians). The Persians called it Takh-e-Jamshid (“Throne of Jamshid”), after a legendary king. The ruins consist of stone columns with elaborate bases and capitals, royal quarters, audience halls, council chambers, courtyards, stone door and window jams, facades and staircases, some with bas-reliefs and sculptures. The roofs are gone. At one time it was surrounded by a 18-meter-high wall, which also is mostly gone.

Darius’s Palace in Persepolis

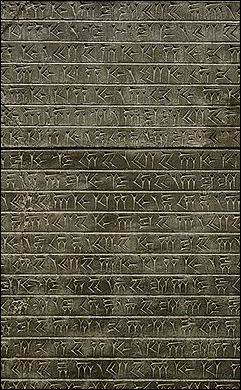

Inscriptions from PesepolisThe monumental doorways are nearly all that remain of Darius’s palace, known as Tachara. Their design, with Egyptian-style cornices, underscores the cosmopolitan tastes of the Achaemenids. The dignitaries that visited Persepolis and presented gifts after walking up the stairways and ramps were awed by reliefs of the achievements of kings and statues of griffins and human-headed lions. In one image a powerful lion brings down a bull---a metaphor of the power of the Persian king. There are many images of soldiers but they are not fighting and their weapons are not drawn. The many images of people from far away lands bearing gifts and putting their hands on each other’s shoulders. Archeologist Kim Codella told National Geographic , “The art of Persepolis was brilliant propaganda.”

On the reliefs the kings are nearly always depicted as bigger and higher than everyone else and are often accompanied by a man who stands behind the throne, swatting away flies (people in the area still pick an herb, reportedly used in ancient Persian times to drive off flies). A motif seen over and over again depicts Darius lifting up a lion by the mane and plunging a dagger into its stomach. At the museum there is an inscription that described Darius as “Great King, King of Kings, King of countries containing all kinds of things.”

Persepolis was rediscovered in the 1930s and dug out of the sand. In 1971, the Shah hosted a lavish party here to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of Persian culture. Unless you visit on Friday, the Muslim Sabbath, there is a good chance you will have the entire place to yourself. [Source:Marguerite del Giudice, National Geographic, August 2008; Fen Montaigne, National Geographic, July 1999]

Buildings in Persepolis

perseopolis

Takht-e Jamshid is a stone platform that stands 12 meters high on a terrace of natural rock and measures 450-x-300 meters and is flanked by plains on three sides and merges with a mountain on the forth side. The complex of 15 palaces and buildings built here were the most important structures at Persepolis. They include the Apadana Palace, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Gate House of Xerxes, the Treasury, the “Harem,” the so called central building and the palaces of Darius the Great, Xerxes, Artaxerexes I and Artaxerxes III. The Grand Stairway is the only entrance to Takht-e Jamshid. At the top is a ramp that leads to the Xerxes Gateway, which features 23-foot-high stone bulls with heads of kings and wings of eagles.

Apadana Palace (within Takht-e Jamshid) is the most impressive ruin at Persepolis. It was used by the king to receive visitors and hold audiences. The roof was once held up by 36 stone columns, each about 60 feet high. The roof is gone but some of these columns remain more or less intact. The most impressive sight is a stairway that was once 300 meters long and was painted with bright colors.

Gateway of Nations (within Apadana Palace) is comprised of the remains of the stairway. It consists of two rows of stairs that have been decorated with reliefs of foreign envoys offering tributes to the Persian monarchy. Particularly impressive is one relief on the side of the stairs that shows bearded envoys bearing flowers climbing the processional staircases. The figures have their feet raised as if they were walking on the staircases. The figures have stiff Egyptian-style postures and Assyrian-style curlicue beards and hairstyles.

The envoys are from all of Persia’s vassal states. They are organized in three rows, offering gifts to the Persian kings. Each envoy is dressed in native costume and offers a special gift. You can see Egyptians with a bull, Elamites leading a lion, Pathans and Sogdians with camels and animal pelts, Armenians with a large vase, Babylonians with cloth, Assyrians with spears and Cilicians with decorated cups. Another relief depicts the “Immortals,” palace guards that were willing to give their lives for the king.

Other Ruins at Persepolis include the Hall of a Hundred Columns, with a large portal, a large courtyard and 110 stairs; the Treasury of Darius (mostly destroyed); the remains of a tent city from the Shah’s party; and a small museum. The Palace of Darius and Palace of Xerex were small palaces that served as the royal living quarters while the king was in town. They were made with reflective black stone, reportedly so the king could see who was behind him.

Tombs in Persepolis

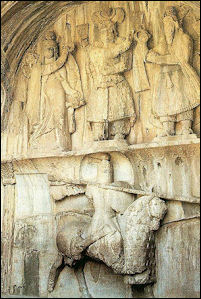

Tomb of Cyrus the Great Naghsh-e-Rostam (two miles north of Persepolis) is comprised of vertical cliffs carved with the Persian tombs believed to belong to Darius the Great, Xerxes, Artaxerexes I and Artaxerxes III. The bottoms of the tombs are several meters off the ground. Facing the cliffs are the remains of a fire sanctuary known as Ka’be-e-Zardosht.

The cross-shaped tombs cut into cliffs that held the bodies of Darius and his immediate successors look somewhat like the tombs in Petra, Jordan. The purpose of a large cube-like building that stands in front of Darius’s tomb is a mystery. Some archeologist have speculated it may have played a role in Achaemenid coronations.

Each tomb has a facade fronted by a porch supported by four columns with Persian bull-style capitals. On the faced the kings are shown respectfully facing the sun and the fire alter. On the lower levels of the cliffs are eight extraordinary Sassanid rock reliefs

Carvings from Persepolis

A carving in a doorway at Persepolis portrays Darius the Great with the famous Persian short sword killing a winged monster. Whether or not there was cultic significance to this scene is not known, but perhaps it is meant to symbolize Darius' defeat of demonic forces. The Tribute Bearer, a stone relief from Persepolis depicting a tribute bearer features a rosette pattern, popular motif in Persian art, at the top of the relief. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

In the carved along the stairway to the Apadana (hall of pillars) at Persepolis, the two outer figures with the fluted headdress are Persians, and the central figure with the domed headdress, short skirt and trousers, is an Elamite. Their rather rigid position with the spear held on the left toe may indicate some sort of salute. Darius the Great constructed this magnificent city, and Alexander the Great demolished it.

Persian Culture

Persian clay seal The ancient Persians practiced Zoroastrianism. Persian men often wore trousers and sported tattoos. They showed their respect to kings by bowing their heads and covering their mouths. Persian women inserted salt-water-soaked sponges in their vaginas in the belief it killed sperm.

Bisotoun Rock in western Iran is a cliff face carved with cuneiform characters that describe the achievements of Darius the Great in three languages: Persian, Babylonian and Elamatic. A sort of Mesopotamian Rosetta Stone, it allowed Sir Henery Rawlinson to decipher the Babylonian and Assyrian languages.

Hockey is one of the oldest stick and ball games. Early forms of hockey were played in ancient Egypt, Greece and Persia.

The Persians. Phoenicians and Greeks built most of their cities on hilltops. Water came from springs and was often carried in subterranean tunnels. The ancient Iranians carried the wares with them wherever the went. A surprisingly number of Iranian artifact gave been found in China dating to the 1st through 5th century B.C.

Persian Art

The Archeology Museum in Tehran is widely regarded as the finest museum in Iran. Many of the best works of art and most impressive artifacts found at archeological and historical sites around the country have been brought here. The museum contains artifacts, carpets, ceramics, glassware, calligraphy and manuscripts and has impressive prehistoric, ancient Persian and Islamic sections. Memorable pieces include a pair of 3000-year-old tweezers, a 14th century manuscript detailing the constellations, and a statue of a woman though to Penelope (Ulysses’ wife).

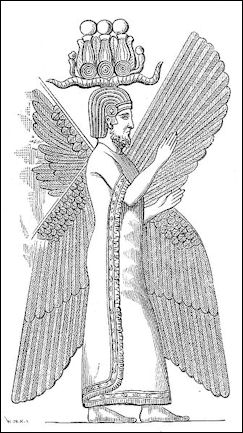

Persian guard

Many of the finest works of art from Persopolis have been brought here. One of the museums most famous piece’s is a larger-than-life bas relief of a 5th century Persian kings receiving subjects. Taken from Persepolis, it features superb craftsmanship and details. The subjects have long curly hair. They are bowing their heads and covering their mouths to show respect.

An ancient Persian bowl dated to 5000 B.C. is 8.5 centimeters high and 13 centimeters wide. It has a round-bottomed shape and straight sides and was made from solid marble ground to an impossibly thin thickness. Another piece from around the same period is the size of a bathtub and was made of conventional clay. Some vessels from this era were made of unusual materials such as chlorite, which is similar to mica, but not flaky; bitumen, a kind of natural asphalt; and green chert, a rock resembling flint. [Source: Tom Baker, Daily Yomiuri, July 2006]

Many old pieces of Persian pottery are decorated with zigzagging geometric patterns and highly stylized and abstract animal images that strongly resemble---coincidently---images found on pottery by Hopi Indians in the American southwest. Some ritual vessels are comprised of three small pots connected by tubes and drains, with a single spout. Exactly how these pieces were used is still not completely understood.

One striking piece is a tall beaker with the silhouette of a ram nears its base. The ram, though rather small, has large horns that loop around a mysterious object that looks like the sun---but is revealed through a window cut to be a river. Other animals that appear repeatedly include fish, sheep, stags with branching antlers and monster-like bears.

The most frequently depicted animal is the zebu, an ox with with a pronounced hump on its neck. Ancient Persians exaggerated the hump so that it was almost as large as the animal’s torso, with the two body parts coming together to form an L. Clay zebu vessels have a spout where the face should be.

Classical Persian Art

Persian relief

Persian art and culture, from the classic Achaemenian period (550 to 330 B.C.) was varied and incorporated many styles of its subject civilizations. In Persian reliefs, the columns and clothes resembled those of the Greeks, the hairstyles and beards resembled those of the Mesopotamians and figures and architecture resembled those of the Egyptians.

Persian art was most like the art in the Mesopotamian culture of Assyria. The figures in Persian reliefs look very much like those in Assyrian reliefs. Persian art that remains today includes life-size silver goats with wings on their backs, masks of human-headed winged lions, gold and silver vessels, silk garments and realist life-size statues. One of the loveliest objects from ancient Persia is a silver-and-gold ibex, dated to 600 to 300 B.C.

The ancient Persians were adept at making tiles and ceramics with wonderful multi-colored glazes and decorations. They decorated their palaces with beautiful vases and tile patterns. They originated a deep blue coloring that became a fixture of Middle Eastern pottery and mosque domes and minarets. Blue coloring was exported to China and was used to decorate some famous Ming era porcelain.

In Persepolis, precious metals were formed into vessels, which could be used as royal tableware and stored away or given as gifts. Craftsmen had incredible skill and developed new style of decorating metals. See Persepolis.

Rhytons---trumpet-like drinking vessels with a sculpted animal or animal head affixed to the narrow, bottom end to serve as a stand---were common in ancient Persia and show up in the art of numerous culture in Central Asia from the classical to medieval period. One of the oldest rhytons is decorated with a clay ram’s heads. It lacks a flat base and has to be lain on its side when not in use, Another rhyton that is also as old is made of silver and is decorated with three ram’s heads whose noses for a tripod allowing the vessel to stand upright. An impressive Achaemenian dynasty rhyton is made of pure gold and stands upright on a base in the shape of an intricately rendered winged lion.

Yazd, a Persian Town

Persian Achaemenian vessel Yazd (east of Isfahan and 420 miles southeast of Tehran) is one of the oldest cities in Iran. Situated between the Great Salt Desert and the Great Sand Desert, it is built around an oasis fed by qanats and was founded, according to some sources, by Alexander the Great, who built a prison here. It was also visited by Marco Polo, who called it a “good and noble city.”

Yazd is a splendid example of a traditional Persian-style mud-walled town. Its remote location sparred it from looting and sacking by Mongols and other invaders. Its dry climate (annual rainfall is only between two to four inches) has helped preserve many old buildings. Yazd is located at an elevation of 1,214 meters. It is hot in the summer, with temperatures sometimes reaching 45̊F, and cold in the winter and pleasant in the spring and autumn.

Yazd also contains Iran’s largest Zoroastrian community (around 12,000 members) . Again, the city’s isolation helped the community survive as long as it did. The main industry in is textiles. For over a thousand years Yazd was famous for its silk. Although weavers who made the town famous are largely gone examples of Yazd silk can be found in the city’s 12 busy bazaars and some traditional weaving factories.

Yazd’s old quarter is a labyrinth of mud-walled building and meandering streets. Some old buildings have wind-catcher towers which bring air to cool the interiors and even make ice by using the wind. The town gets its water from wells but most dwellings in the old quarter still have openings to qanats. There are many fire temples and other points of interest associated with Zoroastrianism. The main atashkadeh is located in the old quarter. It has holds a sacred fire said to have been burning continuously since A.D. 470.

About ten miles outside of town are two abandoned Towers of Silence, which were used from the 17th century until the mid 20th century. Around them are some bones and the remains of a kitchen and camps used by relatives while the dead were being consumed by vultures. Pir-e-Sabz (45 miles north of Yazd) is where Zoroastrians from all over the world gather for religious ceremonies in the summer. An eternal flame found here has been burning for 1,500 years.

Qanats

inside of a qanat

Qanats underlie large areas of Iran, Afghanistan and western China. One of the ancient world’s great engineering feats, they are underground canals and boreholes used to carry water---from melted snow, springs and water tables under hills--- from the highlands to farming areas. Some date back to the time of Alexander the Great.

Qanats follow slopes down hill and are built underground so the water doesn't evaporate in the hot sun. From the sky they look like a long rows of gopher holes, giant anthills or donuts. These holes are outlets for vertical shafts that provide ventilation, and a means of excavating material. Dirt is piled around the entrances to prevent potentially-eroding rainwater from entering the system. Most of the holes are about 10 to 30 feet deep but some drop down almost 100 feet.

Qanats have largely been dug by hand from head wells on high ground near the source of the water to places where the water is used. It is believed millions of hours of forced labor was needed to build them. The long, downward slopping tunnels were dug using the vertical holes to reach the underground tunnel from the surface.

Qanat tunnels have traditionally been communally owned, with villagers splitting the cost of building and maintaining them. Holes used to dig the tunnels are used by laborers today to reach the underground canals, which from time to time have to be cleared of dirt and rubble.

Digging the tunnels and maintaining the qanat system is hard and dangerous work. The men who do the digging, repairing and cleaning have traditionally been highly skilled and well paid. To repair the tunnels workers climb down the entry shaft to the tunnels. There they clean out the tunnels and stabilize weak sections with ceramic hoops. The work is often done by lantern light in extremely cramped conditions---most of the tunnels are barely large enough for a man to crawl through.

Persian Geography

Strategically situated between the Middle East and South and Central Asia, and bordered by the Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman and Arabian Sea to the south, Turkey and Iraq to the west, Afghanistan and Pakistan to the east, and the Caspian Sea and the former Soviet republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan to the north. east, modern Iran covers 636,296 square miles (647,999 square kilometers), which makes it roughly the size of Alaska or three times the size of France or half the size of India. It is the world’s 16th largest country, stretching for roughly 1,400 miles from east to west and 860 miles from north to south.

Iran is relative sparsely populated. It has a population density of 102 per square mile (35 per square kilometers). About 11 percent of Iran is covered by forests; 27 percent is occupied by grasslands; and 9 percent is good for agriculture. Much of the agricultural land is in north and northwest, around the Caspian Sea, irrigated areas along rivers and in mountain valleys. Much of the agricultural land is irrigated. The forest are found predominantly around the Caspian Sea and in the mountains. They are made up mostly of oak, beech, linden and elm trees. There are pistachio forest in southern and eastern Iran.

A wide plateau---that is very hot in the summer and often very cold in the winter---occupies about 90 percent of Iran. Surrounded by high mountains that roughly correspond with the country’s border, it varied in elevation between 3,000 and 5,000 feet and is broken here and there by highlands, enclosed basins and lesser mountain ranges that generally run from northwest to southeast and become more plentiful as one moves eastward towards Afghanistan. The mountains in north and west cut off the rain supply, producing vast deserts..

The Straits of Hormuz separates the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman (a branch of the Arabian Sea, which in turn is part of the Indian Ocean. Iranian Azerbaijan is completely mountainous with many areas above 2,000 meters and the highest peaks above 5,000 meters near Ardebil in the east.

The most significant rivers run along the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. The only navigable rivers, Arvand Rood and Karoon, are located in the Southwest. The Karoon originates in the Zagros mountains and empties in the Shattal-Arab, which in turn flows into the Persian Gulf. Most rivers are only filled with water part of the time and empty into dry interior basins or salt lakes. Most of Iran’s lakes are salt water. In addition to the Caspian Sea, these include the salt lake of Uremyeh which is 85 feet (26 meters) below sea level and has an area of 1879 square miles (4,868 square kilometers).

Deserts and Mountains in Iran

Deserts and semideserts cover about 85 percent of Iran, with true deserts covering about 50 percent of the country. The deserts are concentrated mostly in the center part of the country. The semi deserts in the west are not as dry as those to the east. These deserts resemble deserts on southern California. Plant life includes tamarisk shrubs, and biblical plants like of apple-of-Sodom and Christ-thorn tree.

Lying mostly on the plateau, the desert of Iran include salt deserts and semi-deserts with thorny shrubs. The eastern third of Iran is covered by barren desert with virtually no plant life whatsoever. Here you can find, Iran’s two largest deserts: the Kavir-e-Loot (“Great Salt Desert”) in the northeast and the Dasht-e-Kavir (“Great Sand Desert”) in the southwest. This area receives water from seasonal streams that originate in the mountains and dry up in salt flats and lake beds. There are, however, lots of oases.

Iran’s mountains can be divided into four main groups---Northern, Western, Southern and Central-Eastern Ranges. They surround the central plateau and roughly define Iran’s borders. There are two major mountain ranges: the Elburz (or Alborz) in the northeast and the Zagros in the southwest. The highest peak in Iran is 18,600-foot-high (5,670-meter-high) Mount Damavand. It is north of Tehran in the Elburz mountain range. This range forms a high, thin barrier which separates the coastal Caspian Sea region from the dry interior regions.

The Northern Ranges begins from Mt. Ararat in Turkey, included the Elburz range north of Tehran and continues across northern Iran and links up with mountains in Afghanistan. The Western ranges originate at Mt. Ararat and extend from northwest to southwest, embracing he Zagros Mountain, whose highest peak is 15,592 feet (4752 meters). The Southern Mountains link up with mountains in Pakistan. The Central-Eastern mountains embrace the Karkas, Shirkuh, Hezar and Taftan ranges. The highest peak here is 14,645 feet (4,464 meters) high.

With the exception of mountains in the northeast, most of the mountains in Iran are treeless but they many have highlands and valleys with sparse grass that has traditionally been utilized by nomadic herders and their animals. At the foot of the mountains are scattered oases, many watered by qanats (underground aqueducts). Around these oases are mud-brick towns.

Iranian Climate and Weather

The weather in Iran varies a great deal according elevation and location but generally it is cold or mild in the winter and very hot in the summer and dry throughout the year. The Caspian Sea region has a temperate climate. The northern interior has a dry continental climate. And the southern part of the country has a desert climate. Spring and autumn are pleasant in much of the country. Precipitation is very rare in most of the country and tends to fall in the autumn and winter. The temperatures in the mountains get increasingly cooler as one rises in elevation

The Caspian Sea region receives precipitation throughout the year. But rainfall is heaviest between September and November. It is a little warmer in the winter and a little cooler in the summer than the interior of Iran. The heaviest precipitation is in the mountains and on the windward northern sides of the mountains, facing the Caspian Sea. Most of Iran receives relatively little rain because the mountains in the north, west and south block the moisture carried by the winds from the Caspian Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Persian Gulf.

Precipitation in most of Iran falls in the winter and to a lesser extent the autumn and sometimes the spring. The amount rainfall generally diminishes as one travels westward and southward. The Caspian Sea region gets about 50 to 80 inches (125 to 200 centimeters) of precipitation and southeast receives less than two inches (five centimeters). Tehran gets only about 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain a year. The semideserts in the west get about 15 inches of rain. The barren deserts in the east get around 5 inches..The Persian Gulf area receives little rain but can oppressively humid and hot.

The interior of Iran can be as cold as Siberia in the winter and hot as the Sahara in the summer, in addition to being very windy throughout the year. In the winter the temperatures can drop to -30̊F. The hot, dry summers feature little rain and high temperatures over 100̊F. There can be great extremes of hot and cold on a daily basis and yearly basis. Daytime and nighttime differences of 80̊F have been recorded. Southeastern Iran embraces large deserts, with mild winters and summer high temperatures that average around 110̊F and regularly top 120̊F. The hottest place is Khuzistan at the head of the Persian Gulf. Sometimes temperatures here reach over 125̊F.

Low pressure in Pakistan generates two regular wind patterns over the plateau: the “shamal”, which blows from northwest through the Tigris and Euphrates Valley from February to October; and the “120 day” summer, which sometimes reaches 70mph in the Sistan region. In the Caspian Sea Region the mixing of sea and mountain air brings a nightly cool breeze.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018