ATTILA THE HUN AND ROME

Attila the Hun

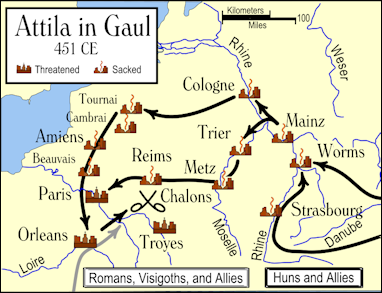

The western part of the Roman Empire began to decline and fall under attack in the A.D. 4th and 5th centuries. Attila and the Huns raided Gaul, Italy and Dacia in the mid 400s. Some have suggested that Rome fell because Roman soldiers could not fight horsemen like the Huns. The Huns first gained a foothold in eastern Europe north of the Danube. Under Attila, they raided Gaul, Italy, and the Balkans. In 447 they attacked Constantinople. In 451, they menaced France and besieged Orleans. In 448, they attacked Rome.

Attila invaded Italy in A,D. 452, but retired without attacking Rome. Attila was within a day's march of Rome when he called off his advance on Rome after a meeting with Pope Leo I who, some scholars say, may have told the invader that a Byzantine army was on the way. Although the Huns raided, attacked and pillaged with great success within Roman territory, no one knows why they didn't invade Rome — a city they probably could have taken.

Some scholars speculate that Attila called off an attack because he missed his family or because there wasn't not enough grass to feed the horses of his horde. Archeologist Dr. David Siren of Tucson University has suggested the Pope frightened Attila with gruesome accounts of malaria and other diseases in southern Italy.

See Separate Article ATTILA AND THE HUNS factsanddetails.com Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe: “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ;

Scythians iranicaonline.org ;

Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ;

The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ;

William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ;

Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ;

Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ;

Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

Hun Conquests

On horses bred for distance, Huns, spread from Volga area into China and Europe between A.D. 304 and 370. The Huns were steppe horsemen who entered Europe from central Asia in A.D. 372. As they moved westward they absorbed German tribal and Roman culture.

The Huns conquered large parts of Europe, Persia and India. The Roman historian Marcellinus dismissed them as barbarians that “fall at every step — they have no feet to walk; they live, wake, eat, drink, and hold counsel on horseback.” The Europeans called them the “Scourge fo God.”

Denis Sinor wrote in the “Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia”: No people of Inner Asia, not even the Mongols, have acquired in European historiography a notoriety similar to that of the Huns, whose name has become synonymous with that of cruel, destructive invaders. Just as the name of the Germanic Vandals has given us the term “vandalism,” the name Hun has been used pejoratively to stigmatize any ferocious, savage enemy. Their greatest ruler, Attila, “the scourge of God,” has become the legendary embodiment of a cruel, merciless leader of barbarians. [Source: The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by Denis Sinor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990]

“There are several reasons why the Huns caught the Western imagination. Firstly, not since Scythian times had any Inner Asian people seriously challenged the equilibrium of the Western World. The Germanic menace to Rome, serious though it was, presented nothing unusual or unexpected – it was part and parcel of Roman political life; the limits of conflict and the patterns of resolution were clearly established. The Huns presented a challenge of a different type: they did not fit into any conventional political category; their very looks, their mode of waging war set them apart from humanity as known to Europe. Secondly, they appeared on the European scene at a time when both the eastern and the western parts of the Roman Empire had to contend with serious internal disorders which weakened their military preparedness. Thirdly, the status quo of the period was disturbed not only by their direct action but even more by their being instrumental in setting into motion the great upheaval of peoples commonly known as the Völkerwanderung.”

Huns Move Into Europe

After the collapse of the Hsiung-nu state in the late first century c.e., the Huns migrated westward to Central Asia and in the process mixed with various Siberian, Ugric, Turkic, and Iranian ethnic elements. Around 350, the Huns migrated further west and entered the Ponto-Caspian steppe, from where they launched raids into Transcaucasia and the Near East in the 360s and 370s. Around 375, they crossed the Volga River and entered the western North Pontic region, where they destroyed the Cherniakhova culture and absorbed much of its Germanic (Gothic), Slavic, and Iranian (Sarmatian) ethnic elements. Hun movement westward initiated a massive chain reaction, touching off the migration of peoples in western Eurasia, mainly the Goths west and the Slavs west and north-northeast. Some of the Goths who escaped the Huns' invasion crossed the Danube and entered Roman territories in 376. In the process of their migrations, the Huns also altered the linguistic makeup of the Inner Eurasian steppe, transforming it from being largely Indo-European-speaking (mainly Iranian) to Turkic. [Source: Roman K. Kovalev, Encyclopedia of Russian History, 2004]

From 395 to 396, from the North Pontic the Huns staged massive raids through Transcaucasia into Roman and Sasanian territories in Anatolia, Syria, and Cappadocia. By around 400, Pannonia (Hungary) and areas north of the lower Danube became the Huns' staging grounds for attacks on the East and West Roman territories. In the 430s and 440s, they launched campaigns on the East Roman Balkans and against Germanic tribes in central Europe, reaching as far west as southern France. The Huns' attacks on territories beyond the North Pontic steppe and Pannonia were raids for booty, campaigns to extract tribute, and mercenary fighting for their clients, not conquests of their wealthy sedentary agricultural neighbors and their lands. Being pastoralists, they wielded great military powers, but only for as long as they remained in the steppe region of Inner Eurasia, which provided them with the open terrain necessary for their mobility and grasslands for their horses. Consequently, Hun attacks west of Pannonia were minor, unorganized, and not led by strong leaders until Attila, who ruled from about 444 or 445 to 453. However, even he continued the earlier Hun practice of viewing the Roman Empire primarily as a source of booty and tribute.

Huns March of Conquest Through Europe

The Huns first appeared in Europe in the 4th century. They show up north of the Black Sea around 370. The Huns crossed the Volga river and attacked the Alans, whom they subjugated. After the Huns defeated the Alans, the Huns and Alans started plundering Greuthungic settlements. The Greuthungic king, Ermanaric, committed suicide and his great-nephew, Vithimiris, took over. Vithimiris was killed during a battle against the Alans and Huns in 376. This resulted in the subjugation of most of the Ostrogoths. Refugees streamed into Thervingic territory, west of the Dniester. The Barbarian invasions of the 5th century were triggered by the destruction of the Gothic kingdoms by the Huns in 372-375. The city of Rome was captured and looted by the Visigoths in 410 and by the Vandals in 455. [Source: Wikipedia]

Huns and Rome With a part of the Ostrogoths on the run, the Huns next came to the territory of the Visigoths, led by Athanaric. Athanaric, not to be caught off guard, sent an expeditionary force beyond the Dniester. The Huns avoided this small force and attacked Athanaric directly. The Goths retreated into the Carpathians. Support for the Gothic chieftains diminished as refugees headed into Thrace and towards the safety of the Roman garrisons. [Ibid]

After these invasions, the Huns begin to be noted as mercenaries. As early as 380, a group of Huns was given Foederati status and allowed to settle in Pannonia. Hunnish mercenaries were also seen on several occasions in the succession struggles of the Eastern and Western Roman Empire during the late 4th century. However, it is most likely that these were individual mercenary bands, not a Hunnish kingdom. [Ibid]

The Huns do not then appear to have been a single force with a single ruler. Many Huns were employed as mercenaries by both East and West Romans and by the Goths. Uldin, the first Hun known by name, headed a group of Huns and Alans fighting against Radagaisus in defense of Italy. Uldin was also known for defeating Gothic rebels giving trouble to the East Romans around the Danube and beheading the Goth Gainas around 400-401. Gainas' head was given to the East Romans for display in Constantinople in an apparent exchange of gifts. [Ibid]

Huns Attack the Roman Empire

In 395 the Huns began their first large-scale attack on the East Roman Empire. Huns attacked in Thrace, overran Armenia, and pillaged Cappadocia. They entered parts of Syria, threatened Antioch, and swarmed through the province of Euphratesia. The forces of Emperor Theodosius were fully committed in the West so the Huns moved unopposed until the end of 398 when the eunuch Eutropius gathered together a force composed of Romans and Goths and succeeded in restoring peace. It is uncertain though, whether or not Eutropius' forces defeated the Huns or whether the Huns left on their own.

The Huns left the Eastern Roman Empire by 398. After this, the Huns invaded the Sassanid Empire. This invasion was initially successful, coming close to the capital of the empire at Ctesiphon, however, they were defeated badly during the Persian counter-attack and retreated toward the Caucasus Mountains via the Derbend Pass.

The East Romans began to feel the pressure from Uldin's Huns in 408. Uldin crossed the Danube and captured a fortress in Moesia named Castra Martis, which was betrayed from within. Uldin then proceeded to ransack Thrace. The East Romans tried to buy Uldin off, but his sum was too high so they instead bought off Uldin's subordinates. This resulted in many desertions from Uldin's group of Huns. Later in 409, the West Romans stationed ten thousand Huns in Italy and Dalmatia to fend off the Hun- eader Alaric, who then abandoned plans to march on Rome.

Huns Attack the Romans Under Attila the Hun and His Brother Bleda

Brothers Attila and Bleda ruled together, but each king had his own territory and people under him. Never did two Hun kings rule the same territory. Attila and Bleda forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus, giving the Huns trade rights and an annual tribute from the Romans. With their southern border protected by the terms of this treaty, the Huns could turn their full attention to the further subjugation of tribes to the east. [Source: Wikipedia]

However, when the Romans failed to deliver the agreed tribute, and other conditions of the Treaty of Margus were not met, both Hunnic kings turned their attention back to the Eastern Romans. Reports that the Bishop of Margus had crossed into Hun lands and desecrated royal graves further angered the kings. War broke out between the two empires, and the Huns capitalized on a weak Roman army to raze the cities of Margus, Singidunum and Viminacium. Although a truce was signed in 441, war resumed two years later with another failure by the Romans to deliver the tribute. In the following campaign, Hun armies came alarmingly close to Constantinople, sacking Sardica, Arcadiopolis and Philippopolis along the way. Suffering a complete defeat at the Battle of Chersonesus, the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II gave in to Hun demands and the Peace of Anatolius was signed in autumn 443. The Huns returned to their lands with a vast train full of plunder. In 445, Bleda died, leaving Attila the sole ruler of the Hun Empire. [Ibid]

Unified Huns Attack the Romans Under Attila the Hun

With his brother gone and as the only ruler of the united Huns, Attila possessed undisputed control over his subjects. In 447, Attila turned the Huns back toward the Eastern Roman Empire once more. His invasion of the Balkans and Thrace was devastating. The Eastern Roman Empire was already beset by internal problems, such as famine and plague, as well as riots and a series of earthquakes in Constantinople itself. Only a last-minute rebuilding of its walls had preserved Constantinople unscathed. An account of the invasion by Callinicus goes: “ The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. ... And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers.” [Source: Wikipedia]

Victory over a Roman army had already left the Huns virtually unchallenged in Eastern Roman lands and only disease forced a retreat, after they had conducted raids as far south as Thermopylae. Our only lengthy first-hand report of conditions among the Huns is by Priscus, who formed part of an embassy to Attila. The war finally came to an end for the Eastern Romans in 449 with the signing of the Third Peace of Anatolius. [Ibid]

Throughout their raids on the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had maintained good relations with the Western Empire, this was due in no small part to their friendship with Flavius Aetius, a powerful Roman general (sometimes even referred to as the de facto ruler of the Western Empire) who had spent some time with the Huns. However, this all changed in 450 when Honoria, the sister of the West Roman emperor, from an arranged marriage. Honoria had reportedly sent Attila a ring and Attila claimed her as his bride and demanded half of the West Roman Empire. [Ibid]

Battle of Châlons

During the Battle of Châlons-Sur-Marne during the Wars of the Western Roman Empire in A.D. 451 an army of Romans and Germanic Visigoths, along with Burgundians, and Franks, led by Flavius Aëtius and Theodoric I drove Attila the Hun's 40,000 member army across the Rhine, ending the invader's thrust into western Europe. The Huns were more hated by the Germans than by the Romans.

Attila has entered Gaul under the pretext of rescuing Honoria, the sister of the West Roman emperor, from an arranged marriage. Honoria had reportedly sent Attila a ring and Attila claimed her as his bride and demanded half of the West Roman Empire.

The Huns besieged Orleans in central Gaul. The Roman-Visigoth army rescued Orleans and forced Attila retreat to the Catlaaunian Plains near Châlons-Sur-Marne, where the Hun army reared around and engaged the Roman-Visigoth army on June 20, 451. The Huns repeated charged the Roman-Visigoth army and were repulsed.

The turning point was when the Visigoth king Theodoric was struck with a javelin and died. The Visigoths were enraged by the death of their king and fiercely attacked the Huns let flank, forcing the entire Hun army to retreat to its camp. By the end of the battle 3,000 Romans and 6,000 Huns were dead.

Attila was almost killed in this battle when he was surround by Germanic horsemen. He had to hide in the back of a covered wagon and fled under the cover of arrows. The day after the battle Attila was allowed to retreat back across the Rhine. The battle was his first and only defeat. The Huns returned two years later and scored a victory in the same area.

The battle was fought near Châlons has been called one of the great decisive battles of the world, because it relieved Europe from the danger of domination by horsemen from Central Asia. Aëtius later became the victim of court intrigue, and was murdered by the jealous prince Valentinian III. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

Defeat of Attila at the Battle of Chalôns

On The Battle of Chalôns, the Gothic historian Jordanes wrote in “History of the Goths”: “The armies met in the Catalaunian Plains. The battlefield was a plain rising by a sharp slope to a ridge which both armies sought to gain; for advantage of position is a great help. The Huns with their forces seized the right side, the Romans, the Visigoths and their allies the left, and then began a struggle for the yet untaken crest. Now Theodoric with his Visigoths held the right wing, and Aetius with the Romans the left [of the line against Attila]. On the other side, the battle line of the Huns was so arranged that Attila and his bravest followers were stationed in the center. In arranging them thus the king had chiefly his own safety in view, since by his position in the very midst of his race, he would be kept out of the way of threatened danger. The innumerable peoples of divers tribes, which he had subjected to his sway, formed the wings. Now the crowd of kings — if we may call them so — and the leaders of various nations hung upon Attila's nod like slaves, and when he gave a sign even by a glance, without a murmur each stood forth in fear and trembling, or at all events did as he was bid. Attila alone was king of kings over all and concerned for all. [Source: Jordanes (fl.c.550 A.D.): “History of the Goths” Chap. 38: The Battle of Chalôns, 451 A.D., William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 322-325]

Chalons disposition

“So then the struggle began for the advantage of position we have mentioned. Attila sent his men to take the summit of the mountain, but was outstripped by Thorismud [crown prince of the Visigoths] and Aetius, who in their effort to gain the top of the hill reached higher ground, and through this advantage easily routed the Huns as they came up. When Attila saw his army was thrown into confusion by the event he [urged them on with a fiery harangue and . . .] inflamed by his words they all dashed into the battle.

“And although the situation was itself fearful, yet the presence of the king dispelled anxiety and hesitation. Hand to hand they clashed in battle, and the fight grew fierce, confused, monstrous, unrelenting — a fight whose like no ancient time has ever recorded. There were such deeds done that a brave man who missed this marvelous spectacle could not hope to see anything so wonderful all his life long. For if we may believe our elders a brook flowing between low banks through the plain was greatly increased by blood from the wounds of the slain. Those whose wounds drove them to slake their parching thirst drank water mingled with gore. In their wretched plight they were forced to drink what they thought was the blood they had poured out from their own wounds.

“Here King Theodoric [the Visigoth] while riding by to encourage his army, was thrown from his horse and trampled underfoot by his own men, thus ending his days at a ripe old age. But others say he was slain by the spear of Andag of the host of the Ostrogoths who were then under the sway of Attila. Then the Visigoths fell on the horde of the Huns and nearly slew Attila. But he prudently took flight and straightway shut himself and his companions within the barriers of the camp which he had fortified with wagons. [The battle now became confused: chieftains became separated from their forces: night fell with the Roman-Gothic army holding the field of combat.]

“At dawn on the next day the Romans saw that the fields were piled high with corpses, and that the Huns did not venture forth; they thought that the victory was theirs, but knew that Attila would not flee from battle unless overwhelmed by a great disaster. Yet he did nothing cowardly, like one that is overcome, but with clash of arms sounded the trumpets and threatened an attack. [His enemies] determined to wear him out by a siege. It is said that the king remained supremely brave even in this extremity and had heaped up a funeral pyre of horse trappings, so that if the enemy should attack him he was determined to cast himself into the flames; that none might have the joy of wounding him, and that the lord of so many races might not fall into the hands of his foes. However, owing to dissensions between the Romans and Goths he was allowed to escape to his home land, and in this most famous war of the bravest tribes, 160,000 men are said to have been slain on both sides.

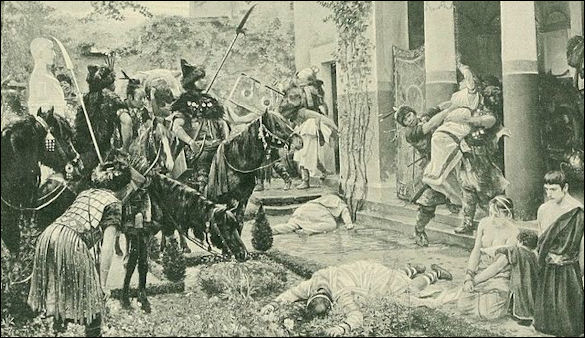

Huns in Italy by Checa

Why Didn’t Attila the Hun Attack Rome Itself

Although the Huns raped and pillaged with great success within Roman territory, no one knows why they didn't invade Rome — a city they probably could have taken. Attila the Hun invaded Italy in A.D. 452. He was within a day's march of Rome when he called off his advance on Rome after a meeting with Pope Leo I who, some scholars say, may have told the invader that a Byzantine army was on the way.

Some scholars speculate that Attila called off an attack because he missed his family or because there wasn't not enough grass to feed the horses of his horde. Archeologist Dr. David Siren of Tucson University has suggested the Pope frightened Attila with gruesome accounts of malaria and other diseases in southern Italy.

Priscus reports that superstitious fear of the fate of the Hun leader Alaric — who died shortly after sacking Rome in 410 — gave him pause. In reality, Italy had suffered from a terrible famine in 451 and her crops were faring little better in 452; Attila's devastating invasion of the plains of northern Italy in 452 did not improve the harvest. To advance on Rome would have required supplies which were not available in Italy, and taking the city would not have improved Attila's supply situation. Therefore, it was more profitable for Attila to conclude peace and retreat back to his homeland. Secondly, an East Roman force had crossed the Danube and proceeded to defeat the Huns who had been left behind by Attila to safeguard their home territories. Attila, hence, faced heavy human and natural pressures to retire from Italy before moving south of the Po. Attila retreated without Honoria or her dowry.

The new Eastern Roman Emperor Marcian then halted tribute payments. From the Carpathian Basin, Attila mobilised to attack Constantinople. Before this planned attack he married a German girl named Ildico. In 453, he died of a nosebleed on his wedding night.

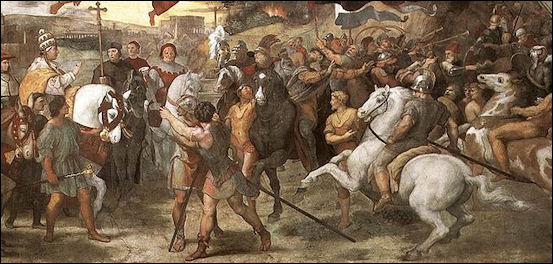

Pope Leo I and Attila

Prosper, a Christian chronicler, writing about 455, gives the following simple account of Leo's famous interview with Attila the Hun in 452: “Now Attila, having once more collected his forces which had been scattered in Gaul [Source: the battle of Chalons], took his way through Pannonia into Italy. . . To the emperor and the senate and Roman people none of all the proposed plans to oppose the enemy seemed so practicable as to send legates to the most savage king and beg for peace. Our most blessed Pope Leo -trusting in the help of God, who never fails the righteous in their trials - undertook the task, accompanied by Avienus, a man of consular rank, and the prefect Trygetius. And the outcome was what his faith had foreseen; for when the king had received the embassy, he was so impressed by the presence of the high priest that he ordered his army to give up warfare and, after he had promised peace, he departed beyond the Danube. [Source: accounts translated in J. H. Robinson, “Readings in European History,” (Boston: Ginn, 1905), pp. 49-51]

Pope Leo and Attila by Raphael

An anonymous later account goes: “Attila, the leader of the Huns, who was called the scourge of God, came into Italy, inflamed with fury, after he had laid waste with most savage frenzy Thrace and Illyricum, Macedonia and Moesia, Achaia and Greece, Pannonia and Germany. He was utterly cruel in inflicting torture, greedy in plundering, insolent in abuse. . . . He destroyed Aquileia from the foundations and razed to the ground those regal cities, Pavia and Milan ; he laid waste many other towns, and was rushing down upon Rome. [This is, of course, an exaggeration. Attila does not seem to have destroyed the buildings, even in Milan and Pavia.]

“Then Leo had compassion on the calamity of Italy and Rome, and with one of the consuls and a lar,e part of the Roman senate he went to meet Attila. The old man of harmless simplicity, venerable in his gray hair and his majestic garb, ready of his own will to give himself entirely for the defense of his flock, went forth to meet the tyrant who was destroying all things. He met Attila, it is said, in the neighborhood of the river Mincio, and he spoke to the grim monarch, saying "The senate and the people of Rome, once conquerors of the world, now indeed vanquished, come before thee as suppliants. We pray for mercy and deliverance. O Attila, thou king of kings, thou couldst have no greater glory than to see suppliant at thy feet this people before whom once all peoples and kings lay suppliant. Thou hast subdued, O Attila, the whole circle of the lands which it was granted to the Romans, victors over all peoples, to conquer. Now we pray that thou, who hast conquered others, shouldst conquer thyself The people have felt thy scourge; now as suppliants they would feel thy mercy."

“As Leo said these things Attila stood looking upon his venerable garb and aspect, silent, as if thinking deeply. And lo, suddenly there were seen the apostles Peter and Paul, clad like bishops, standing by Leo, the one on the right hand, the other on the left. They held swords stretched out over his head, and threatened Attila with death if he did not obey the pope's command. Wherefore Attila was appeased he who had raged as one mad. He by Leo's intercession, straightway promised a lasting peace and withdrew beyond the Danube.

Impact of Huns on Europe

The Huns sold horses and furs, but their biggest profit-making enterprise was selling slaves, most of which were either kidnapped during raids or captured during battles. They also collected large sums of money from ransoming kidnap victims. It is estimated that in one ten year period (between A.D. 440 and 450) the Huns collected six tons of gold in ransoms and bribes. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Although Attila was unsuccessful in his bid to conquer the Roman empire the Huns pushed enough barbarian Germans tribes into the western parts of the Roman empire to destabilize and weaken it, making it vulnerable it to attack from the Germans. The darkest years of the Dark Ages in Europe were after the Hun advances. Europe didn't really settle down again until 11th century after the Huns and the Steppe tribes that followed them — the Magyars — returned to the east.

Huns by Rochegrosse

Invasion from the Huns, Muslims, Magyars and Vikings set off a wave of castle building in Europe. Residences of the aristocracy, monasteries and entire towns were surrounded by massive fortifications, sometimes thirty feet high and ten feet thick, made of cut stone with rubble and dirt fill. for protection. Moats were also dug out at this times and the excavated material was used to crate ramparts.

Immediately after Attila's sudden death in 453, the diverse and loosely-knit Hun tribal confederation disintegrated, and their Germanic allies revolted and killed his eldest son, Ellac (d. 454). In the aftermath, most of the Huns were driven from Pannonia east to the North Pontic region, where they merged with other pastoral peoples. The collapse of Hun power can be attributed to their inability to consolidate a true state. The Huns were always and increasingly in the minority among the peoples they ruled, and they relied on complex tribal alliances but lacked a regular and permanent state structure. Pannonia simply could not provide sufficient grasslands for a larger nomadic population. However, the Hun legacy persisted in later centuries. Because of their fierce military reputation, the term "Hun" came to be applied to many other Eurasian nomads by writers of medieval sedentary societies of Outer Eurasia, while some pastoralists adopted Hun heritage and lineage to distinguish themselves politically. [Source: B.E. Kumekov, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2010]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~\; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018