ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S BIRTH

mosaic depicting the legendary birth of Alexander

Alexander was born in Pella, near the Aegean coast, on July 20, 356 B.C. to Philip II's forth wife Olmypias. He was taught warfare by his father, King Phillip II of Macedonia, religion by his mother Olympias and morality by Aristotle. His childhood was tough. He endured meals with little food and long marches. He excelled at everything he did, hung out with hard-drinking soldiers, horsemen and hunters and was inspired by Homer's tales.

Plutarch wrote: “Alexander was born the sixth of Hecatombaeon, which month the Macedonians call Lous, the same day that the temple of Diana at Ephesus was burnt; which Hegesias of Magnesia makes the occasion of a conceit, frigid enough to have stopped the conflagration. The temple, he says, took fire and was burnt while its mistress was absent, assisting at the birth of Alexander. And all the Eastern soothsayers who happened to be then at Ephesus, looking upon the ruin of this temple to be the forerunner of some other calamity, ran about the town, beating their faces, and crying that this day had brought forth something that would prove fatal and destructive to all Asia. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

“Just after Philip had taken Potidaea, he received these three messages at one time, that Parmenio had overthrown the Illyrians in a great battle, that his race-horse had won the course at the Olympic games, and that his wife had given birth to Alexander; with which being naturally well pleased, as an addition to his satisfaction, he was assured by the diviners that a son, whose birth was accompanied with three such successes, could not fail of being invincible.”

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Greek History (48 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Art and Culture (21 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek Life, Government and Infrastructure (29 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Greece: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Department of Classics, Hampden–Sydney College, Virginia hsc.edu/drjclassics ; The Greeks: Crucible of Civilization pbs.org/empires/thegreeks ; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ; Ancient-Greek.org ancientgreece.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art; The Ancient City of Athens stoa.org/athens; The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org; Classics FAQ MIT rtfm.mit.edu; 11th Brittanica: History of Ancient Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu

Sources on Alexander the Great

Plutarch, a Roman historian who lived during the first century AD (ca. 46-119), wrote his “Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans” intending to draw parallels between great figures of Greek antiquity and Romans of his own time. He chose to compare Alexander the Great with Julius Caesar. In his “Life of Alexander,” Plutarch tells some of the most famous stories related about Alexander. Plutarch wrote: “It being my purpose to write the lives of Alexander the king, and of Caesar, by whom Pompey was destroyed, the multitude of their great actions affords so large a field that I were to blame if I should not by way of apology forewarn my reader that I have chosen rather to epitomize the most celebrated parts of their story, than to insist at large on every particular circumstance of it. It must be borne in mind that my design is not to write histories, but lives. And the most glorious exploits do not always furnish us with the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men; sometimes a matter of less moment, an expression or a jest, informs us better of their characters and inclinations, than the most famous sieges, the greatest armaments, or the bloodiest battles whatsoever. Therefore as portrait-painters are more exact in the lines and features of the face, in which the character is seen, than in the other parts of the body, so I must be allowed to give my more particular attention to the marks and indications of the souls of men, and while I endeavour by these to portray their lives, may be free to leave more weighty matters and great battles to be treated of by others. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

maybe Plutarch

The “Anabasis of Alexander” was composed by Arrian of Nicomedia (A.D. 92-175), a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period. It is considered the best source on Alexander the Great’s the campaigns. On his work, Arrian wrote: “I have admitted into my narrative as strictly authentic all the statements relating to Alexander and Philip which Ptolemy,son of Lagus, and Aristobulus, son of Aristobulus (See Below), agree in making; and from those statements which differ I have selected that which appears to me the more credible and at the same time the more deserving of record. Different authors have given different accounts of Alexander’s life; and there is no one about whom more have written, or more at variance with each other. But in my opinion the narratives of Ptolemy and Aristobulus are more worthy of credit than the rest; Aristobulus, because he served under king Alexander in his expedition, and Ptolemy, not only because he accompanied Alexander in his expedition, but also because he was himself a king afterwards, and falsification of facts would have been more disgraceful to him than to any other man. Moreover, they are both more worthy of credit, because they compiled their histories after Alexander’s death, when neither compulsion was used nor reward offered them to write anything different from what really occurred. Some statements made by other writers I have incorporated in my narrative, because they seemed to me worthy of mention and not altogether improbable; but I have given them merely as reports of Alexander’s proceedings. And if any man wonders why, after so many other men have written of Alexander, the compilation of this history came into my mind, after perusing13 the narratives of all the rest, let him read this of mine, and then wonder (if he can).”

Ptolemy, son of Lagus (367- 283 B.C.) — one of the main sources for Arrian’s accounts — - served with Alexander from his first campaigns, and was the first ruler of the Ptolemy dynasty that ruled Egypt after Alexander’s death. He played a principal part in the campaigns in Afghanistan and India and participated in the Battle of Issus, commanding troops on the left wing under the authority of Parmenion. He accompanied Alexander during his journey to the Oracle in the Siwa Oasis and commanded the campaign that captured the rebel Bessus. During Alexander's campaign in the Indian subcontinent, Ptolemy was in command of the advance guard at the siege of Aornos and fought at the Battle of the Hydaspes River. [Source: Wikipedia]

Aristobulus of Cassandreia (c. 375 – 301 B.C.) — another the main sources for Arrian’s accounts — was a Greek historian who accompanied Alexander on his campaigns. He served throughout as an architect and military engineer as well as a close friend of Alexander, enjoying royal confidence. He wrote an account, mainly geographical and ethnological. It survives only in quotations by others, which may not all be faithful to the original. His work was largely used by Arrian. Plutarch also used him as a reference.

Paul Cartledge of the University of Cambridge wrote for the BBC: “Thanks above all to the literary text known as the “Alexander Romance,” created originally at the great leader's most famous foundation - the city of Alexandria, in Egypt - Alexander has featured internationally as a hero, a quasi-holy man, a Christian saint, a new Achilles, a philosopher, a scientist, a prophet, and a visionary. The more earthy musings of the hero of Shakespeare's Hamlet, in the graveyard scene, are just one chauvinistic illustration of the fact that Alexander has featured in the literature of some 80 countries, stretching from our own Britannic islands (as Arrian, called them) to the Malay peninsula - by way of Kazakhstan.” |::|

Rulers of Macedonia and Alexander’s Timeline

Alexander I coin

Rulers of Macedonia (496–168 B.C.)

Alexander I (496–454 B.C.)

Perdikkas II (454–413 B.C.)

Archelaos I (413–399 B.C.)

Aeropos II (398–395 B.C.)

Amyntas II (395–394 B.C.)

Amyntas III (393–370 B.C.)

Perdiccas III (365–359 B.C.)

Philip II (360/59–336 B.C.)

Alexander III (the Great) (336–323 B.C.)

Philip III Arrhidaios (323–317 B.C.)

Alexander IV (323–310 B.C.)

Olympias (317–316 B.C.)

Cassander (315–297 B.C.)

Philip IV (297 B.C.)

Antipatros and Alexander V (297–294 B.C.)

Demetrios I Poliorketes ("Besieger") (294–288 B.C.)

Pyrrhos of Epeiros (288/7–285 B.C.)

Philip II coin

Lysimachos (288/7–281 B.C.)

Seleukus (281 B.C.)

Ptolemaios Keraunos ("Thunderbolt") (281–279 B.C.)

Antigonos II Gonatas (ca. (277–239 B.C.)

Demetrios II (239–229 B.C.)

Antigonos III Doson (ca. (229–222 B.C.)

Philip V (222–179 B.C.)

Perseus (179–168 B.C.)

Alexander the Great Timeline:

356 B.C.: Born at Pella, Macedonia, to King Philip II and Olympias

336 B.C.: Acceded to throne of Macedon

336 B.C.: In same year, is recognised as leader of Greek-Macedonian expedition against Persia

334 B.C.: Wins Battle of the Granicus River

333 B.C.: Wins Battle of Issus

332 B.C.: Accomplishes siege of Tyre

331 B.C.: Wins Battle of Gaugamela

328 B.C.: Manslaughter of 'Black' Cleitus at Samarkand

326 B.C.: Wins Battle of river Hydaspes

326 B.C.: In same year, troops mutiny at river Hyphasis

324 B.C.: Troops mutiny at Opis

323 B.C.: Dies at Babylon

[Source: Professor Paul Cartledge, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Philip II of Macedon, Alexander the Great’s Father

Philip II of Macedonia. Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.), Alexander the Great's father, was the King of Macedonia and Olympias. He became king of Macedon in 359 B.C. at about the age of 23 and ruled for 23 years. An adept warrior, strategist and warrior, he transformed Macedonia from a loose confederation of tribes and cities into a powerful kingdom and introduced an agile cavalry and long pikes to warfare as he overhauled his army.

Philip II

Philip II was blinded by an enemy's arrow and was lamed in a battle. He enjoyed wine, lavish feasts and women. He had at least seven wives. Like many upper class Greek men, Philip was also reportedly a bisexual. He showed great courage in battle, was a shrewd politician and patronized the arts, filling his court with writers, artists, philosophers and actors.

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: “Philip II of Macedon took a faction-rent, semi-civilized country of quarrelsome landed nobles and boorish peasants, and made it into an invincible military power. The conquests of Alexander the Great would have been impossible without the military power bequeathed him by his almost equally great father. At the very outset of his reign Philip had to confront sore perils in his own family and among the vassals of his decidedly primitive kingdom."

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “During the first half of the fourth century B.C., Greek poleis, or city-states, remained autonomous. As each polis tended to its own interests, frequent disputes and temporary alliances between rival factions resulted. In 360 B.C., an extraordinary individual, Philip II of Macedonia (northern Greece), came to power. In less than a decade, he had defeated most of Macedonia's neighboring enemies: the Illyrians and the Paionians to the west and northwest, and the Thracians to the north and northeast. Phillip II instituted far-reaching reforms at home and abroad. Innovations—improved catapults and siege machinery, as well as a new kind of infantry in which each soldier was equipped with an enormous pike known as a sarissa—placed his armies at the forefront of military technology. In 338 B.C., at the pivotal battle of Chaeronea in Boeotia, Philip II completed what was to be the last phase of his domination when he became the undisputed ruler of Greece. His plans for war against Asia were cut short when he was assassinated in 336 B.C. Excavations of the royal tombs at Vergina in northern Greece give a glimpse of the vibrant wall paintings and rich decorative arts produced for the Macedonian royal court, which had become the leading center of Greek culture." [Source: Collete Hemingway, Independent Scholar, Seán Hemingway, Department of Greek and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org]

See Separate Article PHILIP II OF MACEDON — ALEXANDER THE GREAT’S FATHER --AND HIS, LIFE, LOVES, MURDER, TOMBS AND THE RISE OF MACEDON factsanddetails.com

Olympias, Alexander’s Mother

Olympias

Olympias, daughter of Neoptolemus, king of Epirus, wife of Philip II. of Macedon, and mother of Alexander the Great. Her father claimed descent from Pyrrhus, son of Achilles. It is said that Philip fell in love with her in Samothrace, where they were both being initiated into the mysteries (Plutarch, Alexander, 2). The marriage took place in 359 B.C., shortly after Philip's accession, and Alexander was born in 356 B.C. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911]

The fickleness of Philip and the jealous temper of Olympias led to a growing estrangement, which became complete when Philip married a new wife, Cleopatra, in 337. Alexander, who sided with his mother, withdrew, along with her, into Epirus, whence they both returned in the following year, after the assassination of Philip, which Olympias is said to have countenanced. During the absence of Alexander, with whom she regularly corresponded on public as well as domestic affairs, she had great influence, and by her arrogance and ambition caused such trouble to the regent Antipater that on Alexander's death (323) she found it prudent to withdraw into Epirus.

She remained in Epirus until 317, when, allying herself with Polyperchon, by whom her old enemy had been succeeded in 319, she took the field with an Epirote army; the opposing troops at once declared in her favour, and for a short period Olympias was mistress of Macedonia. Cassander, Antipater's son, hastened from Peloponnesus, and, after an obstinate siege, compelled the surrender of Pydna, where she had taken refuge. One of the terms of the capitulation had been that her life should be spared; but in spite of this she was brought to trial for the numerous and cruel executions of which she had been guilty during her short lease of power. Condemned without a hearing, she was put to death (316) by the friends of those whom she had slain, and Cassander is said to have denied her remains the rites of burial.

Alexander the Great's Relationship with His Parents

Alexander was very close to his mother, Olympias, a princess from Epirus in northwest Greece. She was proud, strong-willed, superstitious, and religious. She boasted she was a member of the orgiastic, ecstatic Dionysus cult that specialized in handling snakes.

Olympias could also be quite ruthless. After Phillip died she killed Philip's last wife Eurydice, and Eurydice's baby daughter, Europa “by dragging them over a bronze vessel filled with fire." Olympia is thought to have spoiled Alexander royally and he idolized here in return. As for his father, Peter Green, a classic professor at the University of Texas, told Smithsonian magazine that Alexander and Philip II had a love-hate relationship marked by “an ambivalent blend of genuine admiration and underlying competitiveness."

Richard Covington wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “From his father Alexander is believed to have inherited courage, quickness of decision and intellectual perceptiveness. His mother, who may have tried to turn their son against his father, gave him a will stronger than Philip’s, as well as fervent religiosity."

Alexander the Great’s Family Roots and His Father’s Vision

Plutarch wrote: “It is agreed on by all hands, that on the father's side, Alexander descended from Hercules by Caranus, and from Aeacus by Neoptolemus on the mother's side. His father Philip, being in Samothrace, when he was quite young, fell in love there with Olympias, in company with whom he was initiated in the religious ceremonies of the country, and her father and mother being both dead, soon after, with the consent of her brother, Arymbas, he married her. The night before the consummation of their marriage, she dreamed that a thunderbolt fell upon her body, which kindled a great fire, whose divided flames dispersed themselves all about, and then were extinguished. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Alexander's family from the Nuremberg chronicles

“And Philip, some time after he was married, dreamt that he sealed up his wife's body with a seal, whose impression, as be fancied, was the figure of a lion. Some of the diviners interpreted this as a warning to Philip to look narrowly to his wife; but Aristander of Telmessus, considering how unusual it was to seal up anything that was empty, assured him the meaning of his dream was that the queen was with child of a boy, who would one day prove as stout and courageous as a lion. Once, moreover, a serpent was found lying by Olympias as she slept, which more than anything else, it is said, abated Philip's passion for her; and whether he feared her as an enchantress, or thought she had commerce with some god, and so looked on himself as excluded, he was ever after less fond of her conversation. Others say, that the women of this country having always been extremely addicted to the enthusiastic Orphic rites, and the wild worship of Bacchus (upon which account they were called Clodones, and Mimallones), imitated in many things the practices of the Edonian and Thracian women about Mount Haemus, from whom the word threskeuein seems to have been derived, as a special term for superfluous and over-curious forms of adoration; and that Olympias, zealously, affecting these fanatical and enthusiastic inspirations, to perform them with more barbaric dread, was wont in the dances proper to these ceremonies to have great tame serpents about her, which sometimes creeping out of the ivy in the mystic fans, sometimes winding themselves about the sacred spears, and the women's chaplets, made a spectacle which men could not look upon without terror.

“Philip, after this vision, sent Chaeron of Megalopolis to consult the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, by which he was commanded to perform sacrifice, and henceforth pay particular honour, above all other gods, to Ammon; and was told he should one day lose that eye with which he presumed to peep through that chink of the door, when he saw the god, under the form of a serpent, in the company of his wife. Eratosthenes says that Olympias, when she attended Alexander on his way to the army in his first expedition, told him the secret of his birth, and bade him behave himself with courage suitable to his divine extraction. Others again affirm that she wholly disclaimed any pretensions of the kind, and was wont to say, "When will Alexander leave off slandering me to Juno?"”

Alexander the Great as a Child

Plutarch wrote: “While he was yet very young, he entertained the ambassadors from the King of Persia, in the absence of his father, and entering much into conversation with them, gained so much upon them by his affability, and the questions he asked them, which were far from being childish or trifling (for he inquired of them the length of the ways, the nature of the road into inner Asia, the character of their king, how he carried himself to his enemies, and what forces he was able to bring into the field), that they were struck with admiration of him, and looked upon the ability so much famed of Philip to be nothing in comparison with the forwardness and high purpose that appeared thus early in his son. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

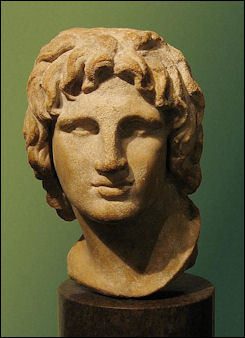

Alexander bust

“Whenever he heard Philip had taken any town of importance, or won any signal victory, instead of rejoicing at it altogether, he would tell his companions that his father would anticipate everything, and leave him and them no opportunities of performing great and illustrious actions. For being more bent upon action and glory than either upon pleasure or riches, he esteemed all that he should receive from his father as a diminution and prevention of his own future achievements; and would have chosen rather to succeed to a kingdom involved in troubles and wars, which would have afforded him frequent exercise of his courage, and a large field of honour, than to one already flourishing and settled, where his inheritance would be an inactive life, and the mere enjoyment of wealth and luxury.

“The care of his education, as it might be presumed, was committed to a great many attendants, preceptors, and teachers, over the whole of whom Leonidas, a near kinsman of Olympias, a man of an austere temper, presided, who did not indeed himself decline the name of what in reality is a noble and honourable office, but in general his dignity, and his near relationship, obtained him from other people the title of Alexander's foster-father and governor. But he who took upon him the actual place and style of his pedagogue was Lysimachus the Acarnanian, who, though he had nothing to recommend him, but his lucky fancy of calling himself Phoenix, Alexander Achilles and Philip Peleus, was therefore well enough esteemed, and ranked in the next degree after Leonidas.”

Alexander the Great Tames Bucephalus

When Alexander was twelve he mounted a wild horse that no one could break, causing Alexander's father to remark, "O my son, look out for a kingdom worthy of thyself, for Macedonia is not large enough to hold you." According to one story Alexander broke the horse after figuring out it reared when it saw its own shadow. Before he mounted him he calmly stroked the horse and pointed him towards the sun so he couldn't see his shadow. The horse, Bucephalas, was with Alexander on his march of conquest. When Bucephalas died at the age of 30 of battle wounds sustained fighting an elephant-mounted army in Pakistan he was given a royal funeral.

Alexander and Bucephalus

Plutarch wrote in “Life of Alexander”: “When Philonieus, the Thessalian, offered the horse named Bucephalus in sale to Philip [Alexander's father], at the price of thirteen talents, the king, with the prince and many others, went into the field to see some trial made of him. The horse appeared extremely vicious and unmanageable, and was so far from suffering himse lf to be mounted, that he would not bear to be spoken to, but turned fiercely on all the grooms. Philip was displeased at their bringing him so wild and ungovernable a horse, and bade them take him away. But Alexander, who had observed him well, said, "What a horse they are losing, for want of skill and spirit to manage him!" Philip at first took no notice of this, but, upon the prince's often repeating the same expression, and showing great uneasiness, said, "Young man, you find fault with your elders, as if you knew more than they, or could manage the horse better." "And I certainly could," answered the prince. "If you should not be able to ride him, what forfeiture will you submit to for your rashness?" "I will pay the price of the horse." [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46–120), “Life of Alexander,” John Langhorne and William Langhorne, eds., “Plutarch's Lives,” Translated from the Original Greek. Cincinatti: Applegate, Pounsford and Co., 1874, pp. 434-439]

“Upon this all the company laughed, but the king and prince agreeing as to the forfeiture, Alexander ran to the horse, and laying hold on the bridle, turned him to the sun; for he had observed, it seems, that the shadow which fell before the horse, and continually moved as he moved, greatly disturbed him. While his fierceness and fury abated, he kept speaking to him softly and stroking him; after which he gently let fall his mantle, leaped lightly upon his back, and got his seat very safe. Then, without pulling the reins too hard, or using either whip or spur, he set him a-going. As soon as he perceived his uneasiness abated, and that he wanted only to run, he put him in a full gallop, and pushed him on both with the voice and spur.

“Philip and all his court were in great distress for him at first, and a profound silence took place. But when the prince had turned him and brought him straight back, they all received him with loud acclamations, except his father, who wept for joy, and kissing him, said, "Seek another kingdom, my son, that may be worthy of thy abilities; for Macedonia is too small for thee..."

Aristotle and Alexander the Great

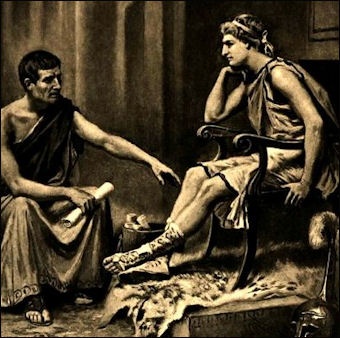

In 342 B.C., Philip II of Macedonia hired Aristotle to teach science and politics to his 13-year-old son Alexander the Great. Little is known about what transpired between the two. Neither Aristotle nor Alexander the Great had much to say about the other afterwards and neither seem to have much influence on the other.

Aristotle tutoring Alexander

Plutarch wrote in “Life of Alexander”: Philip “sent for Aristotle, the most celebrated and learned of all the philosophers; and the reward he gave him for forming his son Alexander was not only honorable, but remarkable for its propriety. He had formerly dismantled the city of Stagira, where that philosopher was born, and now he re-built it, and reestablished the inhabitants, who had either fled or been reduced to slavery... Aristotle was the man Alexander admired in his younger years, and, as he said himself, he had no less affection for him than for his own father.” [Source: Plutarch (A.D. c.46–120), “Life of Alexander,” John Langhorne and William Langhorne, eds., “Plutarch's Lives,” Translated from the Original Greek. Cincinatti: Applegate, Pounsford and Co., 1874, pp. 434-439]

One of the few things that Aristotle was recorded as saying was: “the young man is not a proper audience for political science. He has no experience of life, and because he still follows his emotions, he will only listen to purpose, uselessly." Aristotle appears to have written some pamphlets especially for Alexander. They include On Kingship , In Praise of Colones and The Glory of Rices.

The reason Philip chose Aristotle to be Alexander's teacher is not clear. Aristotle was not a well known philosopher at that time. His father served as court physician for Philip's father (Alexander's grandfather) and perhaps Philips choice was a political move aimed at rebuilding Stagira. Aristotle spent three years with Alexander, until he was 16, when he was made a regent while his father Philip was in Asia Minor.

Aristotle was well paid. Philip also helped Aristotle in his studies of nature by assigning gamekeepers to tag wild animals for him. After Alexander became king of Macedonia he gave Aristotle a lot of money so he could set up a school. While he was in Macedonia, Aristotle made friends with the general Antipater, who ran Macedonia while Alexander was on his campaign of conquest. The friendship was close enough that Antipater was the executor of Aristotle's will. Aristotle no doubt received some financial assistance from him as well.

Alexander had a deep love for Greek literature. He reportedly loved to recite passages from the plays of Euripides from memory. Plutarch wrote: "He regarded the Iliad as a handbook of the art of war and took with him on his campaigns a text annotated by Aristotle, which he always kept under his pillow together with a dagger." In the end Alexander proved more open minded than Aristotle, who tended to view non-Greeks as barbarians.

Plutarch on Alexander the Great and Aristotle

Plutarch wrote: “After this, considering him to be of a temper easy to be led to his duty by reason, but by no means to be compelled, he always endeavoured to persuade rather than to command or force him to anything; and now looking upon the instruction and tuition of his youth to be of greater difficulty and importance than to be wholly trusted to the ordinary masters in music and poetry, and the common school subjects, and to require, as Sophocles says- "The bridle and the rudder too," he sent for Aristotle, the most learned and most celebrated philosopher of his time, and rewarded him with a munificence proportionable to and becoming the care he took to instruct his son. For he repeopled his native city Stagira, which he had caused to be demolished a little before, and restored all the citizens, who were in exile or slavery, to their habitations. As a place for the pursuit of their studies and exercise, he assigned the temple of the Nymphs, near Mieza, where, to this very day, they show you Aristotle's stone seats, and the shady walks which he was wont to frequent. It would appear that Alexander received from him not only his doctrines of Morals and of Politics, but also something of those more abstruse and profound theories which these philosophers, by the very names they gave them, professed to reserve for oral communication to the initiated, and did not allow many to become acquainted with. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Another take on Alexander and Aristotle

“For when he was in Asia, and heard Aristotle had published some treatises of that kind, he wrote to him, using very plain language to him in behalf of philosophy, the following letter. "Alexander to Aristotle, greeting. You have not done well to publish your books of oral doctrine; for what is there now that we excel others in, if those things which we have been particularly instructed in be laid open to all? For my part, I assure you, I had rather excel others in the knowledge of what is excellent, than in the extent of my power and dominion. Farewell." And Aristotle, soothing this passion for pre-eminence, speaks, in his excuse for himself, of these doctrines as in fact both published and not published: as indeed, to say the truth, his books on metaphysics are written in a style which makes them useless for ordinary teaching, and instructive only, in the way of memoranda, for those who have been already conversant in that sort of learning.

“Doubtless also it was to Aristotle that he owed the inclination he had, not to the theory only, but likewise to the practice of the art of medicine. For when any of his friends were sick, he would often prescribe them their course of diet, and medicines proper to their disease, as we may find in his epistles. He was naturally a great lover of all kinds of learning and reading; and Onesicritus informs us that he constantly laid Homer's Iliads, according to the copy corrected by Aristotle, called the casket copy, with his dagger under his pillow, declaring that he esteemed it a perfect portable treasure of all military virtue and knowledge. When he was in the upper Asia, being destitute of other books, he ordered Harpalus to send him some; who furnished him with Philistus's History, a great many of the plays of Euripides, Sophocles, and Aeschylus, and some dithyrambic odes, composed by Telestes and Philoxenus. For a while he loved and cherished Aristotle no less, as he was wont to say himself, than if he had been his father, giving this reason for it, that as he had received life from the one, so the other had taught him to live well. But afterwards, upon some mistrust of him, yet not so great as to make him do him any hurt, his familiarity and friendly kindness to him abated so much of its former force and affectionateness, as to make it evident he was alienated from him. However, his violent thirst after and passion for learning, which were once implanted, still grew up with him, and never decayed; as appears by his veneration of Anaxarchus, by the present of fifty talents which he sent to Xenocrates, and his particular care and esteem of Dandamis and Calanus.”

Alexander Distinguishes Himself Early in Battle

from Philip II's tomb

The crucial phase of the Battle of Chaeronea was led by 18-year-old Alexander and his elite Companion cavalry unit. They found a break in the enemy line and went straight after the legendary crack Thebes unit, the Sacred Band, who had a reputation for fighting to the death of the last man and were buried, according to their code of honor, in a mass grave underneath a monumental lion.

Plutarch wrote: “While Philip went on his expedition against the Byzantines, he left Alexander, then sixteen years old, his lieutenant in Macedonia, committing the charge of his seal to him; who, not to sit idle, reduced the rebellious Maedi, and having taken their chief town by storm, drove out the barbarous inhabitants, and planting a colony of several nations in their room, called the place after his own name, Alexandropolis. At the battle of Chaeronea, which his father fought against the Grecians, he is said to have been the first man that charged the Thebans' sacred band. And even in my remembrance, there stood an old oak near the river Cephisus, which people called Alexander's oak, because his tent was pitched under it. And not far off are to be seen the graves of the Macedonians who fell in that battle. This early bravery made Philip so fond of him, that nothing pleased him more than to hear his subjects call himself their general and Alexander their king. [Source: Plutarch (A.D. 45-127), “Life of Alexander”, A.D. 75 translated by John Dryden, 1906, MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Alexander's birth, Flicker.com

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Canadian Museum of History historymuseum.ca ; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT, Online Library of Liberty, oll.libertyfund.org ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum.Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2018