PAINTING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

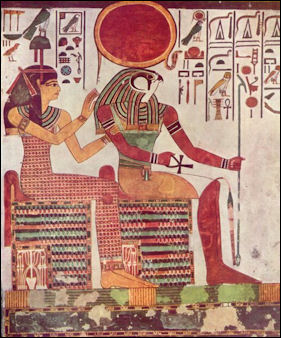

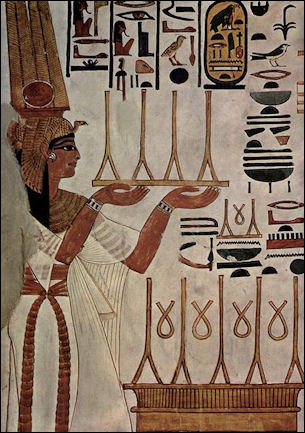

Nefertari tomb painting The Egyptians painted on papyrus rolls, tomb walls, coffin lids and a host of other surfaces. Egyptians used a variety of materials for pigments. They made yellow and orange pigments from soil and produced blue and red from imported indigo and madder and combined them to make flesh color. By 1000 B.C. they developed paints and varnishes using the gum of the acacia tree (gum arabic) as their base.

Described Egyptian painting French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero (1846-1916) wrote: "Their conventional system differed materially from our own. Man or beast, the subject was never anything but a profile relived against a flat background. Their object, therefore, was to select forms which presented a characteristic outline capable of being reproduced in pure line upon a plane surface.”

“The calm strength of the lion in repose, the stealthy and sleepy tread of the leopard, the grimace of the ape, the slender grace of the gazelle and the antelope, have never been better expressed than in Egypt. But it was not easy to project man — the whole man — upon a plane surface without some departure from nature. A man cannot be satisfactorily produced by means of mere lines, and a profile outline necessarily excludes too much of his person."

Categories with related articles in this website: Ancient Egyptian History (32 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Religion (24 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Life and Culture (36 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Egyptian Government, Infrastructure and Economics (24 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Ancient Egypt Magazine ancientegyptmagazine.co.uk; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Egyptian Study Society, Denver egyptianstudysociety.com; The Ancient Egypt Site ancient-egypt.org; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Perspective and Unnatural Poses in Ancient Egyptian Art

The Egyptians never developed perspective. Human heads often looked like the heads of flounders and soles — profiles with two frontal eyes placed on them. The human body was also twisted in an awkward position in which the shoulder faced the viewer but the waist and legs faced sideways. Quantity — such as number of prisoners killed in a battle or animals killed on a hunting trip — was expressed with the items painted in long rows. Ordinary people and servants were generally depicted as considerably smaller than gods, pharaohs, and other important people.

Nefertari tomb painting Different points of view often appeared in the same picture. An image of fisherman might include a side view of the fishermen and a top view of the fish swimming in a pond. It was considered important to show all the important features of a person which some say is why individuals are drawn with combined front and side views. The head is usually a side profile with the eyes drawn as they appear from the front. The shoulders and skirts are also presented from a front view.

Reliefs and paintings were often shown in profile with the eyes, eyebrows, shoulder and upper torso present on one head. While unnatural, these perspectives have become conventions of Egyptian art. Dorthea Arnold, curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, told Smithsonian, "These artistic conventions set the way to show people: axial, not symmetrical, afrontal confrontation, a set number of poses. It was almost like a language. Yet it was elastic, capable of any number of variations within the formula. It showed how creative the artist could be within the canon."

Some scholars say that a painting of Nefertari in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens features the first example of three-dimensional painting, with facing using the technique of Chiaroscuro. The first full frontal representation of a Pharaoh was discovered by Spanish archaeologists in 2004. The 3,500-year-old portrait was found sketched on a plaster-coated board in a Luxor tomb and thought to depict Tutmosis III.

Ancient Egyptian Painting and Expression

Even though Egyptian artists had difficulty with perspective and certain aspects of the human form, they were able to express subtle expression and individuality. They were also very good and recording nature. They produced images of birds and animals that allow modern scientists to identify the species.

The pharaohs were central to Egyptian painting as they were to other art forms. In most cases only the pharaoh, his wife and the people who were conquered by him, or who worked for him were the only people portrayed in Egyptian art. There were set symbols. For example, figures spread out their arms flat like a diver doing a swan dive when they were grieving. A bull's tail hanging down the back of a pharaoh’s skirt symbolized victory.

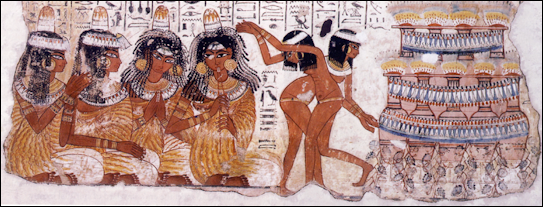

Ancient Egyptian tomb painting from 2500 B.C. graphically illustrated every day along the Nile. People are shown hunting, fishing, herding cattle, building boats, cultivating and irrigating their fields, harvesting crops, playing music, dancing, and making beer. Scribes were usually shown in a seated position like priests with a papyrus scroll and writing materials. Tombs of noblemen contained paintings with inventories of their possessions, to be taken with them to the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian Tomb Paintings

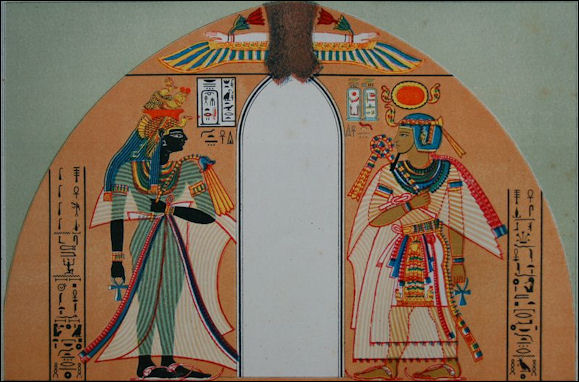

Tombs of kings, queens and nobles were typically decorated with murals with images of deities and people known to the deceased. Sometimes there were images of the daily lives of ordinary people. Images in tombs are often accompanied by texts from the “Book of the Dead” , which sometimes explain what is going on in the picture. Some of the greatest existing works of Egyptian art are the tomb paintings in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, particularly the tomb of Neferteri.

Tombs typically contained: 1) images of the deceased performing tasks from everyday life or doing some great deed or achievement; 2) images of the deceased making offerings or sacrifices to Gods such as Anabus, Isis and Orissis; 3) images of cobras, gods with weapons or scorpions on their head intended to keep evil spirits from entering the tomb and protect the deceased; 4) images of deceased at the gates of the Nether World asking for permission to enter. To pass through each gate the deceased had to say the name of the gate and the god that guards it.

Nebamun tomb fresco of dancers and musicians

The deceased is often pictured proceeding on a journey to the nether world, on which he or she comes in contact with different gods and acquires their power and then caries their symbols with him or her. The ceilings of the tombs often feature a dark blue sky with thin, tightly-packed, five-pointed golden stars. There are often images of farmers, cooks, musicians, rowers — people who could carry out duties in the afterlife.

The head of the deceased is often pictured on the body of the bird Alba, whose duty it was to carry the soul of the dead to the Nether World. Maate, the winged Goddess of Justice and the winged serpent are often present, with her wings spread, on lintels over doorways in the tombs of pharaohs and their wives in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens.

Heirakonpolis contains one of the oldest tomb painting. Created in 3200 B.C., it features stick-like figures. Some of the tombs have been dated to 5000 B.C..

Palettes of Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “Flat stone palettes for the grinding of pigments are particularly associated with Predynastic Egypt, when they were made almost exclusively of mudstone and were formed into distinctive geometric and zoomorphic shapes. Ceremonial palettes of the late Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods are linked with the emerging ideology of kingship, and are especially elaborate, as they are often decorated with carved relief over the entire surface. Following the Early Dynastic period, the importance of palettes diminishes significantly. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Flat pieces of stone upon which colored mineral matter could be ground are known from Paleolithic and Neolithic times in Egypt. In the Badarian period, these artifacts began to be fashioned into elongated forms with notches at each end and were made almost exclusively of the greenish-grey stone procured from the Wadi Hammamat. This material continued to be almost the sole medium for the production of palettes in the Predynastic period. This stone is often mistakenly identified as slate or schist, but it is in fact a form of greywacke, which is an umbrella term that encompasses the other geological stones siltstone and mudstone, and these stones only differ in the size of the grains that make up the rock.

“Such preferential selection of stone for the production of Upper Egyptian palettes, in comparison to the diversity of materials utilized by contemporary groups in Nubia and Lower Egypt for the same purpose, is suggestive of a perceived social value in the Wadi Hammamat rock. Thus, the significance and value of the palettes may have resided as much in their originating area, their visually perceptible qualities or “numina”, as in the material’s amenability to the production of flat pieces of stone.

Amenhotep I

“The vivid green mineral malachite was most often ground upon the palettes of the Predynastic period, at least as far as we know from burial contexts, in which the majority have been found. Palettes thus apparently played a role in the production of cosmetics. In particular, it is often assumed, following Petrie, that the minerals ground upon palettes were used to prepare eye paint. Although the use of green eye paint is attested in Early Dynastic times, corroborating evidence from Predynastic contexts is limited, with a large baked clay female head with eyelids outlined with green from the Naqada I grave H97 at Mahasna being one of the few sources suggestive of the practice. More recently, direct traces of malachite on the faces of several bodies at Adaima have been observed, bolstering Petrie’s original hypothesis. The symbolism of the green color prompts speculation as to a possible connection with regeneration and fertility, properties certainly appropriate for a mortuary context. Galena, hematite, and red ocher are also known to have been processed on the palettes, probably mixed with resins, oils, or fats. There has been the suggestion, on the basis of the excavations at Adaima, that red ocher was more commonly used on palettes in the settlement. Smooth brown or black jasper pebbles were used to grind the pigment, and these types of pebbles often accompany palettes in Predynastic burials.

“The use of both plain palettes and ceremonial palettes waned from the outset of the First Dynasty and flat, shaped, mudstone palettes as a distinct category disappeared by the mid- First Dynasty. It is evident that cosmetics retained a potent symbolic role throughout Pharaonic history, as the inclusion of malachite and kohl in tomb offering lists demonstrates. Examples of rather thick, rectangular grinding palettes, often trapezoidal in cross-section with a rectangular depression, have been recovered from later tombs, such as Old Kingdom mastabas at Giza and Middle Kingdom tombs at Beni Hassan, but no standard material was used in their production, and their forms were rarely elaborate.”

Form of Palettes in Ancient Egypt

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “There was a diversity of palette forms in the Predynastic period; this was first presented in Petrie and Quibell’s Naqada and Ballas publication, although it was not until 1921 that Petrie published his corpus. Predynastic palettes display a clear chronological development, but their long life- histories mean that they are less reliable than ceramics for dating contexts. Many palettes exhibit evidence of a longevity of use, including deep depressions as a result of repeated mineral grinding, or smoothed-down breaks. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In the Naqada I period, palettes were primarily rhomboidal in shape and could vary in size from two centimeters to large examples of over 70 centimeters in length. Some palettes have a pair of horns or a bird embellishing one end. At the end of Naqada I and during Naqada II, palette forms proliferated. While rhomboid examples decreased in frequency, animal forms such as turtles, birds, and, in particular, fish appear, together with shield-shaped examples, the latter often being decorated with antithetically facing bird heads. These forms are repeated across different media and types of objects, appearing on contemporary stone vessels, pins, and combs, and thus, as Wengrow suggests transcend strict distinctions between decorative form, medium, and function. Other animal forms, such as hippopotami, elephants, and gazelles, are far less common shapes for palettes. The appearance of such animals is as if in “silhouette” , with the only interior feature commonly delineated being an eye, which is occasionally enhanced with a small shell or bone ring; occasionally, the edge of fins, feet, or tails are incised. A single hole is often drilled at the central edge of the palette, presumably for suspension. Rough and unworked pieces of mudstone were also used for the grinding of minerals in the Naqada I and II periods, although their frequency is more difficult to determine given that early excavation reports focusing on unusual or special-interest objects tended to be brief. There was a decline in zoomorphic forms from the Naqada III period onwards, with a concurrent proliferation of geometric types, predominately rectilinear, and, to a lesser extent, circular and oviform pieces. These often have incised border lines.

Neolithic paint holder

“A minority of palettes are further elaborated with incised designs. For instance, the el- Amrah palette, from a Naqada IID1 grave, bears the “Min emblem,” while a palette from grave 59 at Gerzeh (the so-called “Hathor” or “Gerzeh Palette”) is carved in rough low relief with a stylized cow’s head surrounded by five stars. The “Manchester” or “Ostrich Palette” is particularly elaborate and is decorated with a relief of a man following a group of ostriches. “Diminutive examples of Naqada I and II palettes have been typologically distinguished from larger palettes through their designation as “magic slates”. These miniature palettes are presumed to have had no utilitarian function, rather only a symbolic one, although they are of the same design and material as their “normal-sized” counterparts. There is, however, a continuum in the size of palettes, thus the assessment of what constitutes the distinction between functional and non-functional palettes is arbitrary. Moreover, any distinction between “utilitarian” and “non-utilitarian” erroneously assumes that there is a dichotomy between the functional and symbolic meanings of palettes.

“Palettes became progressively rarer towards the end of the Predynastic period, from Naqada IIIA2-B onwards, possibly because the source of the material used to make them had been appropriated by the elite and was exploited for other purposes, such as the production of bangles, stone vessels, and, in particular, ceremonial palettes (see below). This reduction in the availability of palettes, together with the progressive plainness of such pieces, contrasts with the ceremonial, elite versions, which are discussed in more detail below. This phenomenon forms part of what has been termed the “evolution of simplicity” in Naqada III, and the “aesthetic deprivation of the non-elite”.

“Attempts to interpret the “meaning” of palette forms tend to appeal to, and thus impose upon prehistory, the ideologies of later periods, such as interpreting the zoomorphic repertoire of palettes in terms of gods like Horus, or interpreting fish-shaped palettes with reference to later Egyptian word-play. At best, such anachronistic interpretations remain speculative. The specificity of the stones used for palettes and grinding pebbles, together with the relatively limited repertoire of designs, are qualities that can be reasonably presumed to have symbolic meanings, but the content of that symbolism currently remains obscureContext Palettes have been found in the graves of both children and adults alike, usually near the hands and face of the deceased. Despite being cited as the most frequent object in Predynastic graves after pottery, palettes were certainly not standard mortuary equipment. On average, only 15 percent of graves in any Predynastic cemetery contained a palette, although grave robbing may have led to an underestimation of their frequency. From Naqada IIIA2-B onwards, this apparently low frequency decreased even further. The majority of the Predynastic palettes are not associated with richly furnished graves. One limiting factor that is often asserted is that palettes were the property of females. Statistical analysis of burial contexts suggests that while palettes are more common in the graves of females, they are not exclusively associated with females, although the accuracy of sexing skeletons found on early excavations must be taken into account.”

Ceremonial Palettes in Ancient Egypt

Narmer Palette, 3100 BC

Alice Stevenson of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford wrote: “In the Naqada III period, within the context of emerging kingship, palettes were appropriated as vehicles to convey the ideology and iconography of a small ruling elite. Skillfully carved in elaborate relief, these palettes are referred to as ceremonial palettes, and share stylistic similarities with other ceremonial objects such as knives and maces. Just over 25 of these ceremonial palettes are known, both whole and fragmentary, and while it is hard to assess how representative these objects are, the small numbers found in comparison to other classes of object do suggest that the ownership of such palettes was restricted. [Source: Alice Stevenson, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The quintessential ceremonial palette is undoubtedly the Narmer Palette, from the “Main Deposit” at Hierakonpolis. On the basis of its style, with the composition arranged using registers and with examples of some of the earliest hieroglyphs, it is considered to be chronologically one of the latest ceremonial palettes, in comparison to an earlier group, on which the images are scattered across the surface. Examples of this latter type include the Hierakonpolis Two-dog Palette, carved with primarily zoomorphic scenes; the Hunters’ or Lion Hunt Palette, depicting hunting scenes; and the Battlefield Palette, bearing defeated naked prisoners. Within the decorated surface, many ceremonial palettes retain a circular area bounded by a raised edge for the grinding of minerals, although indicative traces of such use are absent.

“The motifs on the ceremonial palettes have been the subject of extensive scholarly debate. Early twentieth century interpretations considered palettes such as the Narmer Palette and the Cities (or Libyan) Palette to be historical documents depicting actual events. Such literal interpretations are seldom fully accepted today; rather, more general observations on the overall representational schema on the palettes and the ideology conveyed in this medium occupy academic discourse. For instance, the dominant role of animals, in both their natural and fantastic conceptions, is one focus. These animal motifs have been variously interpreted as ideological referents to themes such as the hunt, chaos and order, containment and rule, as well as social otherness. Notable is the inclusion of what are regarded as Near Eastern motifs on the ceremonial palettes including the serpopards on the Narmer Palette, and the palm tree flanked by two giraffes found on the Louvre Palette and the Battlefield Palette.

“Often, however, such deliberations abstract the surface imagery of the palettes from the artifact itself. Recent discussions have appealed for a more holistic approach that situates ceremonial objects as historically contingent classes of artifact that draw efficacy from the role that their antecedents played in the social lives of communities throughout the Predynastic period. Unlike the common Predynastic palettes discussed above, the provenances of most of these ceremonial palettes are unknown. The final resting place of the Narmer and Two- dog palettes, while recognized as the Hierakonpolis “Main Deposit,” is clearly not the context of their original manufacture or use. Similarly, the most recently discovered palette, the Minshat Ezzat palette, despite being found in situ in an elite three- chambered First Dynasty (Naqada IIIC1) mastaba , is in a poor state of preservation indicative of a longevity of use prior to its interment. A recent attempt to assess a likely context of use is provided by O’Connor, who considers the possibility of a secluded temple context.”

Painted Funerary Portraits from Roman-Era Egypt

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter in the UK wrote: “The term “painted funerary portraits” used here encompasses a group of portraits painted on either wooden panels or on linen shrouds that were used to decorate portrait mummies from Roman Egypt (conventionally called “mummy portraits”). They have been found in cemeteries in almost all parts of Egypt, from the coastal city of Marina el-Alamein to Aswan in Upper Egypt, and originate from the early first century AD to the mid third century with the possible exception of a small number of later shrouds. Their patrons were a wealthy local elite influenced by Hellenistic and Roman culture but deeply rooted in Egyptian religious belief. To date, over 1000 portraits, but only a few complete mummies, are known and are dispersed among museums and collections on every continent.” [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Er-Rubayat in the oasis Fayum some 50 kilometers south of Cairo is the place associated most with these portraits. British Egyptologist W.M. Flinders Petrie “excavated the vast necropolis of Hawara in the Fayum—which lent the genre its alternative name of “Fayum portraits”—according to the then latest scientific standards, took plenty of notes, and published his finds quickly both in public journals and in scholarly books. Until today, his reports provide the fullest account of burials of portrait mummies.

Fayum mummy portrait

“However, as we know from sporadic additional information from other sites, the shallow sand pits in which he found the majority of the mummies were not the norm everywhere. At some places, e.g., at Saqqara, at er-Rubayat, or at Aswan, portrait mummies were buried in re-used rock-cut tombs from the Pharaonic Period. At Antinoopolis, the city founded by emperor Hadrian and named after his beloved Antinoos, and at Panopolis/Achmim, another site yielding a considerable number of portrait mummies, both tomb types were used. Unfortunately, none of the lucky finders, including some archaeologists, provided any reports that give more details about the kinds of tombs, grave goods, burial practices, and rituals surrounding the portrait mummies.

“This problem still exists, although a Polish team lead by Daszewsky made an exciting discovery in 1991/92. In a necropolis near the coastal city of Marina el- Alamein, they found a large tomb consisting of a splendid heroon with a dining hall above ground, with a colonnaded portico facing the sea and an interred courtyard with an altar onto which a burial chamber with burial niches opened. From a stepped ramp connecting the two parts, two smaller undecorated chambers branched off to both sides and included a total of 15 mummies of men, women, and children, which had been placed next to each other on the naked floor; five of them were decorated with painted panel portraits . The variety of tomb types is remarkable—from simple sand pits to re-used older graves to magnificent new tombs built for an aspiring family—but one common feature seems to be the very simple form of deposition of the portrait mummies in entirely inconspicuous cavities or chambers and with only occasional, insignificant grave goods. This suggests that the costly and lavishly decorated mummies were mainly appreciated during the funerary ceremonies and festivals for the dead before burial.

“In the absence of archaeological contexts, the dating of the mummy portraits has been based on two criteria: their style and their antiquarian detail, especially their fashion hairstyles.” Criticism of these methods “is based on the following observations: 1) Research in other artistic genres has shown that there was no linear development of style and that both naturalistic and abstract styles were used simultaneously throughout the Roman era. Thus, any dating based on style should be backed up by other evidence. 2) A systematic comparison of the hairstyles on mummy portraits reveals that the vast majority of them correspond to the fast-changing fashion of hairstyles used by the elite of the rest of the Roman Empire. They, in turn, often followed the fashion of the Roman emperors and their wives, whose images and coiffures can be dated through their depictions on coins. 3) Those hairstyles fashionable in the later third and fourth centuries are almost completely absent from the mummy portraits. These observations led to the suggestion, which is now widely accepted, that the production of mummy portraits increased slowly over the course of the first century, had its peak during the second century, declined dramatically from the early third century onwards, and came to an end around the middle of the third century, with the possible exception of a small number of highly characteristic shrouds from a very limited number of sites of the fourth century. This is well in accordance with the development of portraiture elsewhere in the Mediterranean.” [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Patron -Subjects of Roman-Era Egyptian Painted Funerary Portraits

Fayum mummy portrait

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter wrote: “Some tried to interpret the patrons’ features in terms of their assumed character, an approach that has proven highly problematic. It not only ignores the fact that the images were made to impress their viewers and thus present us with a representation that is at least partly a deliberate construction, but it also underestimates the gap between the ancient and our own culture. Another hot topic of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was the ethnic identity of the individuals, which was equally approached with much confidence through their physical features. [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Anthropologists had long demonstrated that there is no firm methodological basis for identifying peoples on the basis of their facial features alone. Moreover, papyrologists and historians have found that there was so much intermarriage between native Egyptians and immigrants from the entire eastern Mediterranean already during the Hellenistic era that distinct ethnic groups no longer existed in the Imperial Period except for the poor peasant population. Accordingly, focus now shifted to the far more interesting question of social class and the different cultural traditions from which this mixed population took their inspiration and constructed their identities. The deceased were identified as belonging to the rich elite of the local population. Not just the paintings but especially the mummies were extremely expensive, and even more so when they were gilded. Several men present themselves in military guise and thus are likely to be veterans of the Roman army. They received Roman citizenship and other privileges after retirement and belonged to the financial and social elite of their villages.

“One individual is identified by an inscription as a naukleros, a freight contractor for commercial transport by water, an occupation known through papyri to have been particularly profitable. A number of boys stand out through their unusual coiffure with long hair parted on the forehead and bound into a bun in the neck. The ancient author Lucian identified this hairstyle as typical for children of the noblest local elite of Egypt, who trained their sons in the gymnasium and cultivated their Greek heritage. Hairstyles, dress, and jewelry correspond closely to the fashions followed by the elite of the rest of the Roman Empire. These observations are in accordance with the sites from which the portrait mummies derive, almost all of which were cities and villages that had accommodated a large number of Greek immigrants from the Hellenistic Period on, after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander. The same locations were also the preferred settlement sites of veterans in the Roman Period.

“When it comes to religious beliefs, however, the hellenized villages of Egypt had entirely adapted to the Egyptian cult, which also determined their burial rites. Thus, mummification was not just an arbitrary whim. The decoration on many of these mummies consists of scenes and symbols that are entirely intelligible and express the most fundamental ideas of Egyptian belief about resurrection and a cheerful afterlife in the presence of the gods. This twofold anchoring in the Hellenic as well as Egyptian tradition is corroborated by the names that are sometimes inscribed on either the portrait or the mummy itself. We find Greek names as well as Egyptian and a few Latin ones. They indicate a particular affinity with one or the other cultural framework, though papyrological evidence makes it clear that individuals could also have two names from a different background, which they would use according to the traditions a particular social environment drew upon. The patrons of the mummy portraits can thus be identified as members of the affluent local elite of towns and villages that were strongly influenced by Hellenistic and, to a lesser extent, Roman culture, who were keen to be members of the wider elite of the Empire and, at the same time, appreciated the wisdom and promises of Egyptian religion.”

Purpose of the Roman-Era Painted Funerary Portraits

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter wrote: “The fact that many of the painted funerary portraits are highly naturalistic and individualistic and that older individuals are very rare has suggested to some that the likenesses were painted during the lifetime of the individuals depicted, that they had decorated the walls of their houses and were put onto the mummy only after the sitter’s death. During the “Third Reich”, the doubtful results of such attempts were integrated into Nazi propaganda. The alleged identification of a large number of Jews in the mummy portraits served to demonstrate the danger of Jewish infiltration of society already in antiquity. As a reaction, after the Second World War scholars mostly steered clear of any attempts at identifying the portraits’ patrons. It was only in the late sixties and especially from the later nineties of the last century onwards that the question was approached again from a different angle. [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“This assumption has been seriously challenged. As recent studies of both papyrological evidence and anthropological studies of Roman cemeteries have confirmed, the average life expectancy was rather low. CAT scans of preserved portrait mummies did not reveal any obvious discrepancy in age of the painting and body either. Given the very rarity of portrait mummies—Petrie counted one to two for every 100 burials—it is also possible that this honor was only awarded to those whose death was considered particularly tragic, such as a premature demise. Moreover, the background of the paintings often does not cover the entire panel, and only the oval central part was fully covered by paint, in anticipation of what would be visible on the mummy, i.e., framed by the mummy wrappings.

“Some highly realistic portraits painted on the outermost layer of the linen shroud in which the mummy was wrapped could only have been painted at the last stage, thus confirming that naturalistic images could also be created after death— either from memory or based on another portrait of a different function. It is therefore very likely that the portraits were created with their funerary purpose in mind.While mummification and Egyptian scenes and symbols on the mummy secured the survival of the deceased in the world beyond, the realistic portrait alluding to the deceased’s status and life on earth secured his or her survival in the memory of society.”

Mummy Wrapping Painting Techniques and Styles

Fayum portrait

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter wrote: “The portraits were painted in three different techniques on either wooden panels or the outermost layer of the linen shrouds in which the mummies were wrapped. The majority of the portraits were painted in tempera technique with a water- based medium. These paintings can be identified by their even surface and the matt, slightly chalky appearance of the color. Many of them are fast-painted, rather stylized, stereotypical renderings with hardly any interest in a faithful portrayal of their patrons’ features. The second largest group is painted in wax color, possibly sometimes with some oil added. This technique is often called “encaustic” (from Greek enkaio = to burn in). The pigments were mixed in with the molten wax, which was either painted onto the support with a brush or spread out with a spatula-like instrument. Details such as eyelashes were sometimes incised with a tip. These paintings have uneven surfaces and rich and luminous colors, and many of them are very naturalistic likenesses. [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Few examples were painted in a hybrid technique with an emulsion paint, which could be brushed on in extremely thin and delicate lines like tempera but had a shine and richness of color almost like encaustic paintings. The boards were often made from imported wood such as limewood, oak, cedar, or cypress, but also local sycamore, fig, or citrus wood have been identified. The boards could be up to 1.5 centimeters thick—especially in the case of lesser paintings—but often were as thin as just 1.5 to 2 mm. Wood and canvas were occasionally primed but mostly painted upon directly. There are instances where the painting has been traced in black in a first stage. “Most of the pigments are colors derived from natural minerals, but dyes including madder, cochineal, and indigo were also quite common. There are several instances for the use of artificially produced Egyptian blue, and red lead was most likely produced synthetically as well. In many instances, gold leaf or gold paint—a color and material that symbolized eternity—was added for wreaths, jewelry, or as (part of) the background. The wooden panels were fixed over the head of the deceased so that the outermost wrappings held them in place. These wrappings often consisted of layers of narrow linen bands that were wrapped around the body in such a way as to create three- dimensional rhombic patterns or lozenges, the centers of which could be decorated with gilded studs. The feet of these mummies were sometimes encased in cartonnage with the feet indicated on the top and captive enemies painted on the soles of the shoes below. In other cases, the entire mummy was wrapped in one large shroud that was either left plain or else decorated with the body of the deceased or religious scenes and symbols. In a third group, the entire body except the head area with the painting was covered in stucco or plaster painted in red or, more rarely, gilded and decorated with religious symbols rendered in relief.”

Art Historical Significance of Roman-Era Funerary Paintings

Barbara E. Borg of the University of Exeter wrote: “The most striking feature of the painted funerary portraits is their naturalism and immediacy, which delude us to believe we could have met the person somewhere on the street just a day or two ago. While there were occasional attempts at naturalism in Egyptian art, it was only in Hellenistic Greece that the kind of realism we are faced with in the mummy portraits was introduced. Due to less favorable conditions for preservation in that region, very few paintings—painted on stone rather than wood or linen—have come down to us. However, the existence of panel paintings is attested in the written sources, and the naturalistic style is documented in marble portraiture. [Source: Barbara E. Borg, University of Exeter, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“With the Romans, self- representation through naturalistic portraiture became more widespread and an important marker of status. While material evidence for panel paintings is still lacking from the rest of the Mediterranean, there are occasional examples of painted portraits on walls and glass disks, which are rather similar in style to the mummy portraits. This is in accordance with the introduction date of mummy portraits into Egypt. The style of painting must have been introduced by the Greeks already in the Hellenistic Period, at least in Alexandria, while the adoption of realistic portraits into funerary imagery was encouraged by the new requirements of Roman society.

“It is sometimes claimed that Christian icons depended on the mummy portraits. This statement is both right and wrong. It is wrong insofar as the mummy portraits had long been buried when the first icons were produced and could not have served as direct inspiration. It is correct, however, in the sense that icons continued the old tradition of portrait painting of which the mummy portraits have been one group among others. For the history of art and painting, the mummy portraits are not so much important as examples of a particular style or developmental stage. Their significance lies in the fact that they are basically the only panel and canvas paintings that have been preserved from the ancient world. As such, their value can hardly be overestimated.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018