MESOPOTAMIAN FOOD

Mari Baking mold The Mesopotamians consumed barley bread, onions, dates, fruit, fish, lamb, fowls, honey, ghee and milk. Sometimes the best cuts of meat were given to the gods. The Bible refers to people in Abraham's time eating pottage made from red lentils. Major crops included barley, dates, wheat, lentils, peas, olives, pomegranates, grapes, vegetables. Chickpeas originated from southeastern Turkey near Mesopotamia along with lentils and peas, and wheat, and several other wild crop progenitors. Pistachios were grown in royal gardens in Babylonia. See First Villages Agriculture, Livestock

The oldest known recipe dates back to 2200 B.C. It called for snake skin, beer and dried plums to be mixed and cooked. Another tablet from the same period has the oldest recipe for beer. Babylonian tablets now housed at Yale University also listed recipes. One of the two dozen recipes, written in a language only deciphered in the last century, described making a stew of kid (young goat) with garlic, onions and sour milk. Other stews were made from pigeon, mutton and spleen. The Mesopotamians ate ghee and meat from goats, sheep, gazelles, ducks and other wild game. Around 30 percent of bones excavated in Tell Asmar (2800-2700 B.C.) belonged to pigs. Pork was eaten in Ur in pre-Dynastic times. After 2400 B.C. it had become taboo.

Sausages made stuffing spiced meat in a animal intestines were made by the Babylonians around 1500 B.C. The Greeks also at them and the Romans called hem “salsus”, the source of the word sausage.

Book: “The Oldest Cuisine in the World” by French historian Jean Bottéro was published in French in 2002, in English in 2004 and as a paperback in 2011; “The Silk Road Gourmet, Vol. 1, Western and Southern Asia” by Laura Kelley Websites: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World in 2012, (http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/201206/new.flavors.for.the.oldest.recipes.htm); Ancient Food ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Silk Road Gourmet website silkroadgourmet.com/tag/mesopotamia ; Near Eastern Scholars such as Jean Bottéro , Jack Sasson and Piotr Steinkeller are knowledgeable about Mesopotamian food.

Categories with related articles in this website: Mesopotamian History and Religion (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Mesopotamian Culture and Life (38 articles) factsanddetails.com; First Villages, Early Agriculture and Bronze, Copper and Late Stone Age Humans (50 articles) factsanddetails.com Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Mesopotamia: Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; Mesopotamia University of Chicago site mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu; British Museum mesopotamia.co.uk ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Louvre louvre.fr/llv/oeuvres/detail_periode.jsp ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology penn.museum/sites/iraq ; Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago uchicago.edu/museum/highlights/meso ; Iraq Museum Database oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/dbfiles/Iraqdatabasehome ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Oriental Institute Virtual Museum oi.uchicago.edu/virtualtour ; Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur oi.uchicago.edu/museum-exhibits ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org

Archaeology News and Resources: Anthropology.net anthropology.net : serves the online community interested in anthropology and archaeology; archaeologica.org archaeologica.org is good source for archaeological news and information. Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com features educational resources, original material on many archaeological subjects and has information on archaeological events, study tours, field trips and archaeological courses, links to web sites and articles; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org has archaeology news and articles and is a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America; Archaeology News Network archaeologynewsnetwork is a non-profit, online open access, pro- community news website on archaeology; British Archaeology magazine british-archaeology-magazine is an excellent source published by the Council for British Archaeology; Current Archaeology magazine archaeology.co.uk is produced by the UK’s leading archaeology magazine; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com is an online heritage and archaeology magazine, highlighting the latest news and new discoveries; Livescience livescience.com/ : general science website with plenty of archaeological content and news; Past Horizons, online magazine site covering archaeology and heritage news as well as news on other science fields; The Archaeology Channel archaeologychannel.org explores archaeology and cultural heritage through streaming media; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu : is put out by a non-profit organization and includes articles on pre-history; Best of History Websites besthistorysites.net is a good source for links to other sites; Essential Humanities essential-humanities.net: provides information on History and Art History, including sections Prehistory

Types of Foods Eaten in Mesopotamia

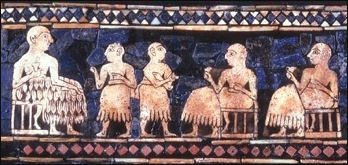

Akkadian banquet scene

A Sumerian-Akkadian bilingual dictionary, recorded in cuneiform script on 24 stone tablets dated about 1900 B.C., lists over 800 different items of food and drink. Included are 20 different kinds of cheese, over 100 varieties of soup and 300 types of bread - each with different ingredients, filling, shape or size. A stone bas-relief discovered at Nineveh describes delicacies such as grasshoppers en brochette and meat-filled intestine casings — perhaps the world's first known sausage. There are records of people eating pickles in Mesopotamia as far back as 2400 B.C.. [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011, Shannon Cothran, CNN.com, August 7, 2009]

One of the earliest accounts of the distribution of barley can be found on a clay tablet from Mesopotamia, written in Cuneiform dating to 2350 B.C. It called for a ration of 30-40 pints for adults and 20 pints for children.

Laura Kelly wrote:“Well-known sources, such as the Sumerian and Akkadian lexicon found on the Urra=Hubullu tablets, as well as Assyrian bas-relief wall panels, show a rich culinary culture. Fruits named or shown range from pomegranates and dates to apricots, apples and pears; vegetables include radishes, beets and lettuce. Sheep and goats were both milked and eaten for meat, while other meat came from cattle, bison and oxen as well as from wild game. Wild and domesticated fowl, fish and shellfish of many varieties were enjoyed, as were milk products ranging from butter and cheese to yogurt and sour cream. These sources depict bountiful harvests at home; vibrant foreign trade and the flow of people in and out of the empire brought additional ingredients and culinary knowledge. [Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com , Laura Kelley (laurakelley@silkroadgourmet.com) has long enjoyed food, travel and cultures. She is author of The Silk Road Gourmet, Vol. 1, Western and Southern Asia, available at www.silkroadgourmet.com]

John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: “Records of deliveries to the royal kitchens at Ur include suckling pigs, wood-pigeons, ducks, lambs and geese. Other texts list many kinds of fresh- and saltwater fish, the preferred kinds being those raised in the reservoirs which were part of Mesopotamia's intricate irrigation system. “Mesopotamia was much more fertile in ancient times than it is today. Chickpeas and lentils - still important crops in today's Syria, Iraq and Jordan - head on Sumerian listing of foods that grew there. But the cornerstone of the Mesopotamian diet appears to have been the onion far - including leeks, shallots and garlic. Sumerians also ate lettuce and cucumber and apples, pears, grapes, figs, pistachios and pomegranates were widely grown. he Sumerians also used a wide range of spices and herbs, including coriander cumin and watercress, says Belgian scholar Henri Limet. That indicates, he says that at least the upper classes enjoyed cuisine that was not only varied in its ingredients but refined in its preparation.” [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011]

Hittite Food: Lard, Bread and Olive Oil

Olives

The Hittites, who were based in present-day Turkey, were contemporaries of the Mesopotamians. They left behind numerous texts on food and food preparation and had many laws related to how certain foods were prepared, cooked and served. The main ingredients of Hittite cuisine were dairy products, meat, grain products and other natural products such as honey. Hittites loved bread and had recipes for as many as 180 types of bread in different shapes and with varying ingredients as well as skewered meat like present-day shish kebab. Hittite food recipes were generally similar to that of contemporary civilizations, especially in regard to meat and dairy dishes, but were unique with regard to the plants used in cooking, as Anatolia has its own unique vegetation. Wine was consumed by the Hittites on regular basis and used for religious festivals and rituals. [Source: Wikipedia]

Harry A. Hoffner, Jr wrote in “Oil in Hittite Texts”: “In an instructions text in Old Hittite handwriting, "high-quality lard" is mentioned at the head of a list of foodstuffs: cheeses, rennet, wheat flour, and bread. Lard was considered a tasty dish even for gods and humans as can be seen from its inclusion alongside of honey, cheese, rennet, sweet milk, and other foodstuffs in two other Old Hittite rituals specifying offerings to the gods. [Source: Harry A. Hoffner, Jr., “Oil in Hittite Texts,” Internet Archive, from Emory/Biblical Archaeology /=/]

“That animal fat was valuable is clearly indicated by No. 90 of the Hittite law code which specifies that, if a dog eats lard (í SAH "oil/fat of a pig"), the owner of the lard is justified in killing the animal and retrieving the lard from the dog's stomach. This same law also proves that Ì SAH was solid and durable enough to have value even after having been subjected to partial digestion in the stomach of a dog. Furthermore, according to the wording of the law, the dog does not lap up the lard, but eats or devours it. [Swine Fat = Lard] /=/ “Butter or ghee (Ì.NUN) was used in the analogical speeches in the Old Hittite incantations: "As (this) honey is sweet, as (this) butter is soft/mild, so may the mind of Telipinu likewise be sweet and mild!". The relative price of butter or ghee is considered below under "Fine Oil;" while its use is noted under "Anointing/Rubbing Horses" and "Burning Oil."

“When olive oil is mentioned alongside breads on lists, the latter are "thin breads" (i.e., pita). In some passages a sample (anahi) of "thin bread" is dipped in olive oil and placed on the hearth .The same verb (suniya-) for "dipping" the bread in olive oil is used in the Hurro-Hittite bilingual in a passage about a dog who steals a freshly baked loaf of bread from an oven, dips it in oil, sits down, and eats it (Hoffner 1994). In a prayer of Muwatalli II, the cult officiant breaks successively three loaves for the Sun goddess of Arinna, for the Storm god pihassassi, for Hebat, and for the Storm god of the Sky, dips them in honey and í.DôG.GA, and places them on the offering table of the respective deity (KUB 6.46 i 40-56; cf. Pritchard 1969 and Lebrun 1980). When used in rituals, olive oil is associated with "fine/good oil" (í.DôG.GA) and honey (KBo 5.2 i 12).

“Oil was used in the preparation of many foods, especially the breads and pastries. Among these foods we may mention NINDA.í and NINDA.í.E.Dƒ.A. The latter was a special delicacy made from a wide spectrum of sweet and oily ingredients: oil, sheep fat, milk, butter, and honey. It has been compared to Turkish helva. A stew or thick soup flavored with oil was considered a particular delicacy and was often served to the king. Olive oil and honey were also poured on top of roasted mutton as a kind of sauce. Singer (1987) thinks this was done to make it tender.” /=/

Book: "Hittite Cuisine", published by Alpha Publishing (08-2008) in Turkey. Various books are written in Turkish about the Hittite cuisine and the Hittite University in Çorum in Turkey has published articles about Hittite cuisine recently.

Archaeology of Mesopotamian Food

Ur feastJohn Lawton wrote in Aramco World: “One text that has come down to us is a Sumerian-Akkadian bilingual dictionary, recorded in cuneiform script on 24 stone tablets about 1900 B.C.. It lists terms in the two ancient Mesopotamian languages for over 800 different items of food and drink. Included are 20 different kinds of cheese, over 100 varieties of soup and 300 types of bread - each with different ingredients, filling, shape or size. [Source: John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011 /~/]

“Other archaeological evidence suggests that a complete shopping list of available Mesopotamian foodstuffs would be at least twice as long: A stone bas-relief discovered at Nineveh, for example, shows servants carrying choice delicacies - among them grasshoppers en brochette - to the royal table, while a satirical text about meat-filled intestine casings indicates that the Mesopotamians made, and presumably ate, the world's first known sausage. /~/ “Nonetheless, the actual dishes the Mesopotamian peoples ate, and how they cooked them, remained a mystery until recently. Although Sumerian lexicographical lists and economic records indicate that a wide range of foodstuffs was consumed, not a single recipe existed from this early Mesopotamia period. /~/

“Indeed, the earliest cookbook we knew about - and it is more of a menu reference list than a step-by-step guide - is De Re Coquinaria, a Roman work probably compiled in the fourth century, a good 20 centuries after the Mesopotamian kingdoms flourished. Lacking information, scholars had depicted the peoples of ancient Mesopotamia as consumers of nothing more interesting than sorry mushes.” /~/

Jean Bottéro and Deciphering Mesopotamian Cuisine

John Lawton wrote in Aramco World: “That was the case until eminent French Assyriologist Jean Bottéro, himself an accomplished chef, succeeded in deciphering three cracked, caramel-colored clay tablets written in Akkadian around 1700 B.C.. Though his predecessors had thought they contained pharmaceutical formulas, the tablets in fact recorded the world's oldest extant recipes, revealing a varied Mesopotamian cuisine of striking richness, sophistication and artistry. [Source:John Lawton, Aramco World, April 6, 2011 /~/]

Vase from Uruke

“Bottéro spent several years studying the three recipe tablets, which are part of Yale University's 40,000-piece Babylonian Collection, the largest assemblage of Mesopotamian antiquities in the United States. Acquired by Yale in 1933, baked in a kiln to preserve them in 1942, and copied by hand onto paper in 1952, the tablets had not received much attention until recently. Now they are among the collection's most talked-about pieces; just looking at them reported the New Haven Register imaginatively, "you almost can smell a 4,000-year old leg of lamb bubbling in a sauce thick with mysterious Mesopotamian herbs." /~/

“Additionally, says Bottéro, truly recreating the Mesopotamian dishes is practically impossible because of the difficulty in matching the original ingredients precisely, and because of the tantalizing shorthand in which the recipes were written. In fact, he confided in a letter to Jack Sasson, who translated his findings into English, "I would not wish such meals on any save my worst enemies." /~/

“But Bottéro is convinced that the Mesopotamians - and not only Mesopotamia royalty - enjoyed them. "It is my opinion," he wrote in the The Journal of the American Oriental Society, "that in any given culture, imagination and refinement, whether culinary or otherwise, are by themselves easily contagious. We might imagine, therefore, that even small households must have introduced some experimentation into their everyday eating, within the limits of their economic' capabilities. "In other words, I do not believe that the cuisine of even the most modest of [Mesopotamian] households is necessarily reflected in the sorry mushes and doleful mastications to which we Asyriologists have consigned them so sadistically.” /~/

Yale Culinary Tablets

“Tucked away in a dark room of a Gothic-style library at Yale University, what may be the world's oldest known cookbooks are shedding light on an ancient cuisine,” AP reported in 1988. Known as the Yale culinary tablets, the three small Mesopotamian clay slabs, dating to about 1700 B.C., contain what are probably the oldest known written recipes, according to William W. Hallo, the curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection and a professor of Assyriology and Babylonian literature. [Source: The Associated Press, January 03, 1988]

Yale culinary tablet

The tablets, the largest of which measures 7 by 9 1/2 inches, are covered with compact, tiny lines of cuneiform writing. Unlike hieroglyphic panels from ancient Egypt, the recipes are not much to look at. They are three brownish clay tablets, with the two largest being about the size of ordinary sheets of paper, filled with the puzzling geometric shapes that comprise cuneiform. Scholars conjecture that the recipes were preserved in a library that was attached to a temple. Temples at that time were centers of ritual animal slaughter, which provided another context for dining. Although the tablets probably have been in Yale's Babylonian collection for decades, their contents have only become generally known in the last few years. The collection, which has about 40,000 items, recently celebrated its 75th anniversary.

''Three of our clay tablets are by far the most ancient collections of recipes from anywhere in the world,'' Hallo told the New York Times. ''There are no competitors in sight at the moment.'' Scholars date these clay tablets from the 18th century B.C., roughly during the time of Hammurabi, and situate them in the Kingdom of Larsa, territory that now falls within southern Iraq.''They are written in a mix of first- and second-person,'' Mr. Hallo said, ''suggesting that we have a kind of record made from the oral dictation of a master chef to an apprentice.'' The texts are written in Akkadian using cuneiform, the wedge-shaped script used widely in ancient Mesopotamia.

''They are recipes and as such practically a unique genre that one simply has not encountered before in cuneiform literature,'' Mr. Hallo said. The common Mesopotamian rarely, if ever, tasted the dishes described in the tablets, Mr. Hallo said. He cited the quality and quantity of the ingredients as well as the elaborate instructions for their preparation. ''It's clear they are festive meals of some kind of presumably the elite of the population,'' Mr. Hallo said. Much of the Babylonian population ''subsisted on the barest necessities,'' he said.

Nor were the tablets intended for uses similar to today's common cookbook, according to scholars. ''A cook - who along with almost everyone else, was illiterate - would not have had the slightest idea of writing books for other cooks, who were as unlettered as he,'' Mr. Bottero wrote. ''I don't know whether they had a scribe sitting there in the kitchen and saying, 'First you take a pigeon and split it in half,' '' said Ulla Kasten, museum editor of the Yale Babylonian Collection.

Hand copies of the Larsa recipes first appeared in print in 1985, in Volume 11 of the Yale Oriental Series-Babylonian Texts. Mary Inda Hussey's copies of the recipes were presented in a collection titled ''Early Mesopotamian Incantations and Rituals,'' though Mr. Hallo acknowledged that the recipes were not quite either. Mr. Hallo later assigned translations of the Larsa recipes to a French scholar, Jean Bottéro. His French translations appeared (with an introduction in English) in 1995 as ''Mesopotamian Culinary Texts.''

Mesopotamian Grains

emmer wheat

Laura Kelly wrote in silkroadgourmet.com:“Kanasu = Emmer Wheat. (Kunasu in Akkadian). Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum), also known as farro in Italian. Emmer a proto-wheat or awned-wheat that was one of the first domesticated crops. Emmer is one of the ancestors of spelt (Triticum spelta). The use of it in Mesopotamian recipes probably refers to wheat flour, but possibly to wheat berries. [Source: Laura Kelly, silkroadgourmet.com, March 16, 2010, ]

“Qaiiatu = rolled oats or pounded oats or oat flour. Used roasted and added to the stews, soups and pilafs represented in the Yale Babylonian culinary tablets.

“Samidu = Semolina. Assyrian samidu, Syrian semida “fine meal”, Greek semidalis “the finest flour”. A fine flour called semida in the Talmud. Semida is the Targum Yonatan translation for solet – also meaning “fine flour”. Probably used in broths, soups and stews to thicken the liquid (much as corn starch is commonly used today), or could be used to form small “dumplings” as is done in Central Asian cooking today.

“Tuhu = Cracked ryeberries or wheatberries. In TCM Bottero called these beets. However, Tuh’hu is the accepted word for bran in Old Assyrian. I think, however, that instead of denoting “bran” it might be used for a cracked wheat, rye or a wild grass berry. From a culinary point of view, the cracked rye or wheatberries make more sense than bran.

Mesopotamian Meat and Dairy Products

Herodotus wrote in 403 B.C.: “There are likewise three tribes among them who eat nothing but fish. These are caught and dried in the sun, after which they are brayed in a mortar, and strained through a linen sieve. Some prefer to make cakes of this material, while others bake it into a kind of bread.”

Laura Kelly wrote in Saudi Aramco World: “Sheep and goats were both milked and eaten for meat, while other meat came from cattle, bison and oxen as well as from wild game. Wild and domesticated fowl, fish and shellfish of many varieties were enjoyed, as were milk products ranging from butter and cheese to yogurt and sour cream.” [Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com ]

Assyrian banquet scene

Kelly wrote in silkroadgourmet.com: “Siqqu = Salted Fish or other salted meat. Bottero defines this as garum like the Carthaginian fish sauce often associated with the Romans. There is nothing that I can find that defines Siqqu as a sauce. References only point to fish and salt as the principal ingredients. Additionally, one reference records a person complaining that the siqqu they bought is not moist. How can liquid not be moist? Siqqu may have been eaten with a selection of fruits like dates and date-plums and splashes of fruit vinegar. [Source: Laura Kelly, silkroadgourmet.com, March 16, 2010, silkroadgourmet.com/tag/mesopotamia ]

“Zamzaganu = Field birds. Sumerian, Old Babylonian. A possible compound noun of zamzam (bird) and ganu (field).

“Hirsu = A cut slice sliver, piece, portion. Akkadian. In TCM Bottero gives no definition for this. He states that it appears before words designating “leg and mutton?” – so it is possible that it refers to the shank. Lamb or sheep shanks, at least in that context.

“Kisimmu = Sour Cream or Yogurt. Undefined in OCM. Called a sort of cheese in TCM. Clearly defined as a sour milk product in multiple sources in reference 1. Unclear whether it would have been moist like yogurt, partially dried like chaka or fully dried like dry kishk.

“Tiktu = A dairy product. Possibly a type of kashk. In Assyrian – Diktu. Likely to be a product like kashk, because in OCW, it is mixed with beer to create a sauce. In OCW, Bottero does not define this, but uses it to denote a sort of flour. It is possible that the term “tiktu-flour” used by Bottero is a mixture of kashk and cracked wheat as is done in the Levant. The combination is called Kishk and the dried flour is the base for a traditional hearty soup or gravy with meat, onions, and garlic. The sauce or gravy is eaten by scooping out with flat bread.

“Zurumu = Small intestine or lining thereof. Surumu as small intestine in Akkadian.. Moran specifies that Surumu is Akkadian for “lining” of part of the digestive tract. Used like intestines and lining of digestive organs are used today: ubiquitously in soups and stews, stir fries etc. for flavor and texture. Tripe or Chit’lins.

Mesopotamian Vegetables and Fruits

dates on a date palm

Fruits and vegetables consumed in Mesopotamia included pomegranates, dates, apricots, apples pears, onions, radishes, beets and lettuce. Laura Kelly wrote in silkroadgourmet.com: “Suhutinnu = A root vegetable. Possibly a parsnip, turnip or carrot. Sahutinnu in Assyrian (Begins with letter “shin”). In the Babylonian tablets translated by Bottero, it is always used “raw”. Ref 1 states that it is an alliaceous plant, but there is no evidence to support that it is anything other than a root vegetable. Tablets simply report that they are “dug up”. [Source: Laura Kelly, silkroadgourmet.com, March 16, 2010, silkroadgourmet.com/tag/mesopotamia ]

“Baru = Dates. In Early Old Babylonian, the word “barUD” means dates. According to Bottero in Textes Culinaire Mesopotamien(TCM), the tablet reads, “Clean some baru and add it”. This could be referring to pitting the date or removing the stone before it is added to a dish. (ref 2).

“Zanzar = Date-plum, (fruit of Diospyros lotus, the Caucasian persimmon). Zanzaliqqu is specified as a type of tree bearing fruit (sometimes said to be inedible). When date palms are unripe they are very bitter and inedible as raw fruits. They change significantly as they ripen and dry and lose their tartness. Same word as Zarzar(u). (An alternative reading of zararu as sarsar(u) or sansar(u) (a type of locust) are possible zarzar is separated out as a plant because of its association with the verb ittabsi in ARM 2 107. That said, the concept of using “locusts” to make siqqu is questionable – although locusts were regarded as food items as shown in representative art.)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and Yale University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018