AFRICAN ROCK ART AND PAINTING

San Thomas river rock art Rock art was a common form of expression among ancient peoples. It has been found on every continent except Antarctica. Africa has more rock art sites than any other continent and these sites are widely distributed across the continent. Rock art has been in numerous sites in the Sahara (See Below) and in southern Africa in the Kalahari and Drakenburg mountains of South Africa, Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

The oldest known — in Namibia in southern Africa — is are estimated to be around 27,000 years old but may be as old as 40,000 years old. By contrast the oldest rock art in Europe is about 30,000 years old. In Australia some works may be 75,000 years old but the jury is still out on this date.

There are thousands — probably tens of thousand and perhaps hundreds of thousands — of rock art sites. Many lie undiscovered because they are situated in remote areas of the Sahara or in other places rarely visited or not visited at all by humans. The art has endured sun, sand and occasional thunderstorms.

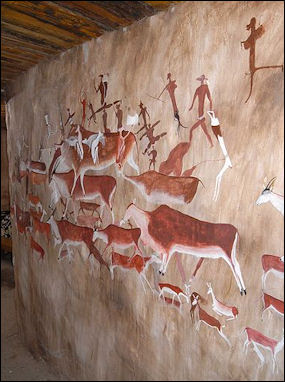

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Rock paintings and engravings are Africa's oldest continuously practiced art form. Depictions of elegant human figures, richly hued animals, and figures combining human and animal features—called therianthropes and associated with shamanism—continue to inspire admiration for their sophistication, energy, and direct, powerful forms. The apparent universality of these images is deceptive; content and style range widely over the African continent. Nevertheless, African rock art can be divided into three broad geographical zones—southern, central, and northern. The art of each of these zones is distinctive and easily recognizable, even to an untrained eye. [Source: Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas,Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org October 2000 \^/]

“Not all rock art in these three zones is prehistoric; in some areas these arts flourished into the late nineteenth century, while in other areas rock art continues to be made today. In the Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa, a number of rock paintings depict clashes between San (Bushmen) people and European colonists mounted on horses and armed with rifles. Many of the Drakensberg works use subtle polychrome shading that gives their subjects a hint of three-dimensional presence. The product of many authors, time periods, and cultures, the flowing naturalism and lively sense of movement of the best rock art attests to the conviction of masterful hands and trained eyes.

Websites and Resources on Prehistoric Art: Chauvet Cave Paintings archeologie.culture.fr/chauvet ; Cave of Lascaux archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en; Trust for African Rock Art (TARA) africanrockart.org; Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com; Australian and Asian Palaeoanthropology, by Peter Brown peterbrown-palaeoanthropology.net

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

Books on Cave Art: “Cave Art” by Jean Clottes (Phaidon, 2008); “The Cave Painters” by Gregory Curtis (2006), with interesting insights offer by a non-specialist; “The Nature of Paleolithic Art” by R. Dale Guthrie (2005); “Images of the Past” by Douglas I. Price and Gary M. Feinman (McGraw-Hill, 2006); “The Human Past: World Prehistory & the Development of Human Societies’ edited by Chris Scarre (Thames & Hudson, 2005); “The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Palaeolithic Cave Painting” by André Leroi-Gourhan (Cambridge University Press, 1982); “The Origin of Modern Humans” by Roger Lewin (Scientific American Library, 1993).

Books on African Cave Art: 1) “Origins: The Story of the Emergence of Humans and Humanity in Africa” edited by Geoffrey Blundell (Double Storey, 2006); “African Rock Art: Paintings and Engravings on Stone” by David Coulson, and Alec Campbell (Abrams, 2001); 3) “Early Art and Architecture of Africa” by Peter Garlake (Oxford University Press, 2002); 4) “Rock Art in Africa: Mythology and Legend” by Jean-Loïc Le Quellec (Flammarion, 2004); 5) .”Images of Mystery: Rock Art of the Drakensberg” by J. David Lewis-Williams (Double Storey, 2003); 6) “San Spirituality: Roots, Expression, and Social Consequences” by J. David Lewis-Williams and David G. Pearce. (AltaMira Press, 2004); 7) “Zambia's Ancient Rock Art: The Paintings of Kasama” by Benjamin Smith (Livingstone, Zambia: National Heritage Conservation Commission, 1997)

Southern African Rock Art

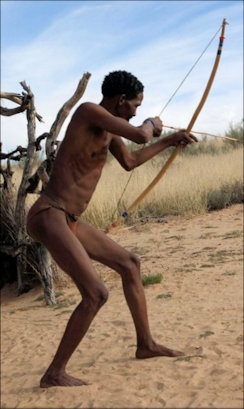

Bushman hunting

Rock art by hunter-gatherers, herders, and/or later farming communities occurs in almost all countries in Africa. There is, however, a distinctive set of Southern African traditions, with regional and temporal variation, in Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland, and Lesotho. [Source: Janette Deacon, 2002, Southern African Rock Art Project (SARAP). Full Text see icomos.org/studies/sarockart ]

Archeologist Janette Deacon wrote: “Many individual sites and images - both paintings and engravings - are masterpieces of human creative genius that illustrate a combination of sophisticated ideas and beliefs, exquisite and unusual detail, extraordinary imagination, and artistic mastery of the chosen media. Collectively, over a period of nearly thirty millennia in the subcontinent, the artists recorded significant interchanges of human values - particularly with respect to religious and ritual practices - that cannot be recovered from stone artefacts and other inanimate remains.

“There is excellent ethnographic information available from indigenous people in certain key areas that has assisted in the understanding and authentic interpretation of the meaning and motivation of the art - a feature that is missing in many other regions of the world. Paintings and engravings of successive traditions have been done at selected places and areas over a long time period and the integrity of this relationship is still intact, incrementally adding to the tangible and intangible significance and power of these places and the landscape; and The shamanistic inspiration for much of the art demonstrates the time depth and nature of the human quest for supernatural power in this part of the world.”

Geoffrey Blundell of the University of the Witwatersrand wrote: “This zone stretches from the South African Cape to the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia formed by the Zambezi River. The rock painting of this region is characterized by exquisitely minute detail and complex techniques of shading. Engravings are also found in this zone, generally on boulders and rocks in the interior plateau of southern Africa, while paintings are found in the mountainous regions that fringe the plateau. There are only a few places where paintings and engravings are found in the same shelter. Aboriginal San hunter-gatherers made most of these paintings and engravings. [Source: Geoffrey Blundell, Origins Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2001 \^/]

“While the rock art of southern Africa is different from that of the central and northern zones, it is not homogenous. There is, for example, great diversity between the art of the Matopo Hills in Zimbabwe, the Brandberg in Namibia, and the Drakensberg Mountains in South Africa. Nevertheless, scholars have suggested that a great deal of San art throughout southern Africa may be explicitly and implicitly linked to San shamanic religion. Principally, a great deal of San art depicts their central most important ritual, the healing or trance dance, and the complex somatic experiences of dancers. \^/

“In addition to San rock art, there are also rock paintings and engravings made by closely related Khoi pastoralists. These people acquired domestic stock through close interaction with Bantu-speaking people some 2,000 years or more ago. Although there is some evidence that they also made engravings, Bantu-speakers' rock art is characterized by finger painting in a thick, white pigment. Often found superimposed over San or Khoi paintings, this art is implicated in initiation rituals and in political protest and is not a shamanistic art. \^/

Southern African Rock Art Sites

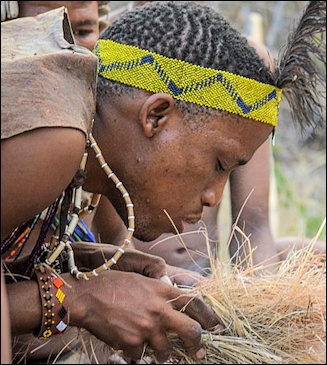

Bushman making a fireerg

A summary of rock art databases in Southern African countries indicates that there are at least 14 000 sites on record, but that many more exist than have been formally recorded. There are probably well in excess of 50,000 sites in the region as a whole, with a conservative estimate of more than two million individual images.

The main sites are: 1) Kondoa-Irangi District in Tanzania (hunter-gatherer paintings with unusual technique and content); 2) Dedza-Chongoni District in Malawi (agriculturist paintings with good ethnographic detail); 3) Manica Province in Mozambique (well-preserved hunter-gatherer paintings); 4) Kasama District in Zambia (well-preserved hunter-gatherer and agriculturist paintings with good ethnographic detail); 5) Matopos National Park in Zimbabwe (high quality, well preserved, detailed hunter-gathere paintings in natural landscape); 6) Tsodilo in Botswana (large number of well preserved herder paintings in natural landscape); 7) Brandberg in Namibia (large number of high-quality, well-preserved hunter-gatherer rock paintings in natural landscape); 8) Twyfelfontein in Namibia (large number of high-quality, well-preserved hunter-gatherer rock engravings in natural landscape); 9) uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park in South Africa (large number of high-quality, detailed and well-preserved hunter-gatherer rock paintings in natural landscape); 10) Xam Heartland in South Africa (cultural landscape with excellent ethnographic records and high quality rock hunter-gatherer engravings).

With the exception of the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park in South Africa, Tsodilo in Botswana, and the Brandberg in Namibia, few areas have been thoroughly searched and recorded. The densest known concentrations of rock art occur in parts of Lesotho, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Zambia, and Zimbabwe The lowest numbers of recorded sites are in Angola, Malawi, and Mozambique.

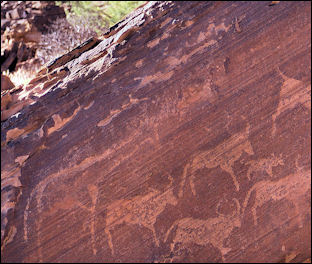

The region has both rock engravings (petroglyphs) and rock paintings (pictographs). There are no reliable records to indicate the relative percentage of paintings to engravings, but painting sites are probably in the majority. In general, both paintings and engravings have similar themes and images, but the engravings tend to include less detail and fewer human figures.

The distribution of the two techniques is largely governed by geology. Engravings occur out in the open and are usually, but not exclusively, associated with igneous rocks such as dolerite. Such rock formations tend not to form shelters or caves. Rock paintings, on the other hand, are most common in areas where there are caves or rock shelters in outcrops of granite and in sedimentary rocks formations of limestone, sandstone and quartzite. It is rare, but not unknown, to find both rock paintings and engravings together at the same site.

In several cases in hunter-gatherer, herder, and agriculturist traditions, there is ethnographic evidence that rock art has been used to enhance the power and significance of particular places in the landscape. The paintings or engravings were placed there because it was a rainmaking or initiation site, adding intangible value to the place. In a few cases, such as Kasama (Zambia) and the /Xam heartland in South Africa, there are ethnographic records that explain the significance of the place. Good examples are Tsodilo (Botswana), the Matopos (Zimbabwe), the Brandberg (Namibia), and the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park and the /Xam Heartland (South Africa).

Tsodilo Hills and Rhino Cave Botswana — Maybe 100,000 Years Old

According to the British Museum:Tsodilo Hills, located in north-west Botswana, contains around 400 rock art sites with more than 4,000 individual paintings, and has been termed the “The Louvre of the Desert”. Designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2001, Tsodilo comprises four main hill: Male Hill, Female Hill, Child Hill and North Hill with paintings occurring on all four. This region shows human occupation going back 100,000 years. At sunset the western cliffs of the Hills radiate a glowing light that can be seen for miles around, for which the local Juc’hoansi call them the “Copper Bracelet of the Evening”.

The paintings at Tsodilo are unique in comparison to other San|Bushmen rock art in both techniques and subject matter. San|Bushmen paintings are well-known throughout southern Africa for their fine-line detail because they were brush painted, but those at Tsodilo are finger painted. In addition, 160 depictions of cattle are portrayed in the same style as wild animals, and more geometric designs appear here than anywhere else. Tsodilo animal drawings are larger and the geometric designs simpler than those found elsewhere. In comparison to human figures elsewhere in southern Africa, those at Tsodilo appear without bows and arrows, clothing or any forms of personal ornamentation. In addition, numerous cupules and grooves are incised and ground into rock surfaces, sometimes close to painted rock art sites and some on their own. For the residents of Tsodilo, the hills are a sacred place inhabited by spirits of the ancestors.

The subject matter of red finger-painted depictions can be divided into animals, human figures and geometric designs. Unusually, animals, mainly large mammals and cattle have been depicted in twisted perspective with two horns and two or four legs displayed in silhouette. Human figures are schematic and depicted by two intersecting lines, a vertical line which thickens at the middle to indicate hips and buttocks, and the other a horizontal shorter line joined at the middle to represent a penis. Female figures are depicted with two legs and show two projections near the top indicating breasts.

Rhino Cave is regarded as one oldest occupied sites. In Rhino Cave there are 346 small round depressions ground into the rock, known as cupules, carved into a vertical wall and nearly 1,100 at Depression Shelter. The purpose or meaning of cupules is unknown; they may have denoted a special place or the number of times a site had been visited. However, we have no dates for any of the cupules and even if they are adjacent to a rock art site, they are not necessarily contemporaneous. From their patina and general wear it has been proposed that some cupules may date back tens of thousands of years to the Middle Stone Age. If paintings also existed at this time they have long since disappeared.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Tsodilo Hills, Botswana britishmuseum.org

Traditions and Styles of Southern African Rock Art Sites

San Rock Art in Cederberg In broad terms, there are three rock-art traditions in the region with distinctive styles and content that are largely the result of differences in the cosmology and beliefs of Stone Age hunter-gatherers, of Stone Age herders, and of Iron Age agriculturists. Within these traditions, and often cross-cutting them, there are further differences in the techniques used to paint and engrave.

Paintings: As elsewhere in the world, the most common pigment used for rock paintings is red ochre, with some paintings in maroon, yellow, black, and white. There is some ethnographic evidence that the pigment was mixed with a variety of binders such as blood, egg, fat and plant juices, but the exact recipes are not known. The techniques applied in the majority of paintings can be summarized as follows:

Fine-line paintings, almost exclusively the work of hunter-gatherers, in red or yellow ochre, white clay, or black charcoal or manganese oxide, done with a brush or other fine instrument, using techniques such as the following: A) Outline of the image with a single line (rare everywhere); B) Outline of the image with the interior filled with lines of the same colour (characteristic of Tanzania, with some examples elsewhere); C) Monochrome image with the colour blocked in (most common almost everywhere); D) Outline in one colour with the image filled in with another slightly different colour; E) ichrome, in which two blocks of colour are used in the same image; F) Polychrome in which three or more colours are used in the same image (most common in Namibia, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Lesotho); G) Shaded polychrome in which several colours blend into each other to create depth and shading (most common in Lesotho and the Drakensberg region of South Africa); H) Handprints and finger-dots

Paintings done with a finger or very broad brush or applicator, most often by herders and agriculturists, often bold and highly stylized designs that include domesticated animals, in: A) Monochrome red, white, or black (yellow rare); 2) Bichrome (rare); 3) Handprints, both plain and decorated.

3) Engravings: Rock engravings in all traditions were made most commonly by removing the weathered outer surface of rocks such as dolerite to create a colour contrast with the underlying unweathered rock. This could be achieved by using another harder rock such as quartz or chalcedony. The weathered surface was either scraped away over the whole area of the image, or the image was outlined in a single line, or the weathered rock was pecked out in a chopping motion. Some engravings show extraordinary artistic skill with careful details of skin folds, eyes and posture delicately portrayed. Engravings are also found on rocks where there is little or no colour contrast but where a large flat expanse is exposed, for example on ancient glacial pavements in the Northern Cape Province in South Africa.

So-called cupules and grooves, sometimes in regular patterns, have been made in relatively soft rock types where the colour contrast between the surface and underlying rock has been less important than the granularity of the rock. Many of these were probably not 'art', although they may have had a ritual use.

Dating of Southern African Rock Art Sites

Khoekhoen rock art Namibia The engravings and paintings on the rocks of Southern Africa dates back at least 27,500 years and persisted in some areas until the 20th century AD. The oldest date is the average calculated from fifteen radiocarbon dates on charcoal from an occupation layer in Apollo 11 cave in southern Namibia. Seven small painted slabs, on rock that was not derived from the cave wall or floor, were recovered during two excavations in 1969 and 1972. The next oldest date is from the Matopos in Zimbabwe, where a spall that had flaked off the painted wall in the Cave of Bees was found incorporated in the deposit in the floor. Charcoal from the relevant layer was dated to about 8,500 B.C, giving a minimum age for the original painting.

The oldest dated rock engravings in the region come from Wonderwerk Cave in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Five small slabs with clearly identifiable fine-line rock engravings of animals and non-representational geometric patterns, and another six with lines that may have been part of engravings, were found in different layers. Associated charcoal dated the oldest to about 8,200 B.C. and the youngest to about 2000 years ago. Cation ratio dates on rock engravings from open sites in South Africa also gave preliminary results of between 10,000 and 2000 years. Relative dating of the weathered crust on engraved surfaces on a small sample of South African rock engravings suggests that the fine- line style is the oldest, and that the pecked and scraped engravings were done more recently.

Geometric zigzag patterns, combined to make diamond shapes and engraved on two small pieces of hard ochre, have been found in a cave at Blombos on the southern coast of South Africa; associated with Middle Stone Age artefacts. A layer of dune sand overlying the deposit has been dated at 77,000 years ago by optical luminescence. Although the find is claimed by some to be the earliest art the archaeologists who excavated the site argue only that people at that time were capable of abstract thought and design. Similar designs are found on bone artefacts and ostrich eggshell dating within the last 18 000 years, but are not common in either rock paintings or rock engravings.

Most of the art was done by hunter-gatherers whose traditions persisted in south-eastern South Africa until the A.D. 19th century. In some countries, such as Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique, where there are no reports of hunter-gatherer style paintings that include domesticated animals or images of the colonial era, the hunter-gatherer art is estimated to be older than A.D. 1000.

Within the last 2000 years, herders and Iron Age agriculturist people entered the region from the north and added to the corpus of rock art with different styles and content. The oldest art in these traditions is generally thought to be less than 1500 years old and the most recent paintings and engravings were done in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In some areas in South Africa, Zambia, and Malawi, agriculturist art was still being practised for initiation rituals in the late twentieth century.

Ethnography of the Southern African Rock Art Sites

There is a wealth of ethnographic information from the 19th and 20th centuries that can and has been used successfully to interpret many of the metaphors and symbols in hunter- gatherer and later agriculturist art dating back hundreds and even thousands of years. This information gives an unparalleled insight into the meaning and context of rock art. An understanding of altered states of consciousness, and its role in shamanism and rock art as developed by researchers David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson. has in turn helped to identify the source of some of the metaphors found in the Palaeolithic rock art in western Europe. With the exception of Australia and North America, very few rock-art regions elsewhere have such detailed sources for interpretation.

San rock art Namibia The ethnographic records provide considerable evidence in Southern Africa that hunter-gatherer rock paintings and rock engravings were part of religious practices for rain- making, healing, and other shamanistic activities such as out-of-body travel and the control of game animals. These practices involved altered states of consciousness that enabled medicine people or shamans to access supernatural power through certain animals or through ancestral spirits. The wide distribution of this rock-art tradition, from South Africa to Tanzania, provides evidence for a broad high-level similarity in the cosmology of Southern African hunter-gatherer peoples. There are nevertheless important regional differences in the way that shamanistic experiences were perceived and used and in the metaphors that were transferred to the art.

For example, the beliefs of the /Xam San that were recorded in the 1870s led to an understanding in the 1970s of the reason why the eland was the animal most commonly depicted in the rock art in the south-eastern region in South Africa. The work of anthropologists and psychologists amongst 20th century San in Botswana and Namibia enabled some of the /Xam records to be interpreted and better understood. By combining the information from these diverse sources, Vinnicombe concluded that the eland was the pivot around which the social organization and beliefs of the Drakensberg San revolved. Lewis-Williams described how the eland played a key role in boys' and girls' initiation, and its role in healing and rainmaking because it was believed that associating with the eland could bring the medicine-person or shaman closer to god and supernatural power. Shamans in trance would feel as though they were transformed into eland, as is clear in many paintings of therianthropes with human and eland body parts that are combined in one image. In other areas such as Zimbabwe and Namibia, however, the eland is less common than animals such as the kudu and the giraffe. This suggests regional variation in the ritual significance of particular animals.

There is relatively little ethnography that has been applicable to herder rock art, and indeed there is only circumstantial evidence that the schematic and highly stylized art with a wider range of geometric patterns, best represented at Tsodilo (Botswana), was done by early herders. This art is attributed to herders because it includes domesticated animals, and because in places where it occurs with the earlier tradition it tends to be superimposed on what is clearly hunter-gatherer art. Herder art is also found above and below hunter-gatherer art. A good example is the Limpopo Valley, where there was a brief period of interaction between the two groups in the A.D. 1st millennium.

Agriculturist rock-art displays some general similarities within the region and is quite distinct from the hunter-gatherer art in several respects. It tends to be bolder, less detailed, more schematic, and with a smaller range of colours and subject matter. In some areas the paintings are called 'late whites' because where superimposition occurs they are always on top and they are done in white paint with a finger rather than a brush. Local traditions and ethnographic records in Zambia and Malawi indicate some of this art was part of secret male and female initiation practices and of rituals such as rainmaking. The meaning of the designs is known only to the initiated.

Content of Southern African Rock Art Sites

The content of the rock art varies within the region, but there are several themes that are sufficiently widespread to indicate broad, high-level geographical and temporal continuity within the Southern African hunter-gatherer, herder, and agriculturist belief systems over the period in which rock paintings and rock engravings were done. The most significant similarities are the persistent occurrence of illustrations of and metaphors for altered states of consciousness or trance experience, particularly in the art of the hunter-gatherers. These experiences are evident in the postures in which people are illustrated, the consistent selection of certain animals in preference to others, and in the presence and incorporation of geometric patterns that depict entoptic phenomena 'seen' during trance.

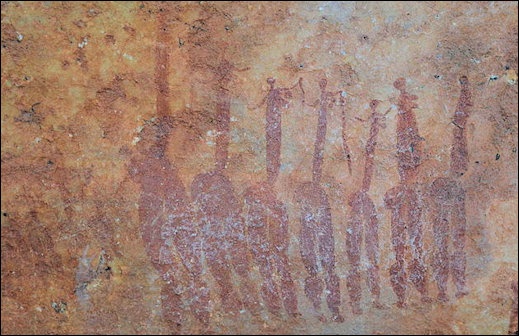

In hunter-gatherer art people are shown in postures such as bending from the waist, lying down horizontally, or with contorted limbs. Additional details such as bleeding from the nose or a red line that sometimes has white dots emanating from the back of the neck or the feet may be seen, as well as the transformation of people into animals and animals into people. Processions of dancing people or groups of clapping women record the dances that helped shamans go into trance. Healers, shown touching sick people to draw out the arrows of sickness, may be associated with arrows, they may have animal heads, or may be sweating or bleeding from the nose. Rainmakers may be shown in close contact with large rain animals such as elephant, hippo, or eland, or with huge animals that are not identifiable to species. People in deep trance may be shown collapsing as if dead, or swimming underwater with fish or fish tails, or flying, with or without wings.

Images of transformed medicine-people with animal heads and other features (therianthropes) are especially detailed in paintings in the Drakensberg (South Africa and Lesotho), in Zimbabwe, and in the Brandberg (Namibia). Animals may also be shown with human hind legs. Therianthropes occur in parts of Angola, Botswana, Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, and Tanzania, but are not as common as they are in the other Southern African countries.

Differences in the content of the art can be seen in the posture and dress of the people who are illustrated. For example, paintings of people in Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania have dramatic hairstyles that are not seen so often in the art further south. In contrast, there are many more paintings in the south of people wearing cloaks, some of which are elaborately decorated.

As noted above, there are variations in the frequency of certain animals depicted in the rock paintings and engravings of the region. These variations are not a mirror of the distribution of fauna, but an indication of the animals that the artists and their society regarded as significant in their religious and ritual practices. The eland predominates in the south-east, the eland and elephant in the south-west, the rhino is prominent in some areas, while in Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Tanzania the kudu and giraffe reign supreme.

In some parts of South Africa, Zambia, and Malawi the rock art is dominated by agriculturist paintings depicting symbols significant during initiation ceremonies and ritual practices. A stylized image of the crocodile or lizard is most common in some areas where it is a symbol of power, while in others domesticated cattle are more prevalent. Agriculturist art also records activities associated with colonial times such as trains, motor vehicles, aircraft, wagons, horses, camels, and other forms of transport.

Schematic designs illustrating entoptic phenomena with dots, zigzags, grids, wavy lines, nested u-shapes, concentric circles, sunbursts, and vortices are widespread and occur in all rock-art traditions, not only in Southern Africa but elsewhere in the world as well. In Southern Africa they are more common in rock engravings than in paintings, but are nevertheless seen in paintings throughout the region. In the hunter-gatherer tradition they are subtly integrated into the fine-line paintings and engravings; in the herder art they are often more common than images of people or animals; and in the agriculturist art they may be combined with other stylized designs. The presence of these entoptic patterns in all three traditions emphasises their connection with altered states of consciousness and, therefore, the link between the art and trance experience that persisted in various forms over a long period of time and through major changes in economy and beliefs.

San painting of animals

Bushman Art

Bushmen paintings can be found throughout most of southern Africa and as far north as Tanzania. The highest concentration of them is in South Africa, where many are located near the top of high escarpments, places Bushmen have traditionally scanned the horizon for game. Most of them are painted on the walls of rock shelters under a protective overhang which also served as the Bushmen's home. The painting themselves are similar to shelter paintings and rock art found in the Sahara and North Africa as well as famous Stone-Age painting in Lascaux, France and Altamira, Spain. [Source: Alfred Friendly, National Geographic, June 1963]

The Bushmen are people who have lived as hunters and gatherers until recent times. In his 1874 treatise on Bushmen mythology Dr. W. H. Bleek wrote, "This fact of Bushman paintings illustrating Bushman mythology...gives at once to Bushman art a higher character and teaches us to look upon it as products not as mere daubings of figures for idle pastime, but as truly artistic conception of the ideas which most deeply moved the Bushman mind and filled it with religious feeling."

The Bushmen used paint brushes made from the tails and manes of the black wildebeest. The horns of antelopes were used as paint pots. Pointed pieces of bone were used to make fine details. Most of the paintings were done in red, and yellow. Red and brown pigments appear to have been concocted from a finely ground and possibly roasted iron oxide mixed with a binder like animal fat, milk, urine, blood or honey. White was made from zinc, and black from manganese or charcoal. The paint penetrated the sandstone shelter surfaces, which is one of the main reasons why the painting have held up all these years. The iron oxide is thought to have some from nodules of sandstone that can be pried out of rock and split open like melons.

As to the age of the Bushmen paintings, some anthropologists say that because they were exposed to the air (unlike the European paintings which were often found in nearly sealed off caves) the colors were unlikely to last more than a 1,000 years. Most are probably between 300 and 800 years old. Some of them show Bantu and their cattle. Others depict European soldiers with guns and horses that were painted between 1820 and 1870.

Tourist who visit the cliff hanging Bushmen shelters often complain about the wearying climbs and wonder why they bothered. After watching a small duiker climb effortlessly among the rocks scholar Berry Malan told Friendly "To the Bushman the climb was no harder than to the duiker. He was used to it from infancy.

Bushman Art Subjects

Bushmen paintings portrayed themselves, their enemies, but most of all they depicted the animals they hunted for food — rhebok, eland, springbok and hartebeest — and the animals they were often in contact with — elephants, giraffes, leopards, lions, snakes, and birds. Some paintings were drawn with life-size proportions but more often than not they consisted of tiny inch-high figures.

Most painting by bushmen were of large animals and hunting scenes, and many of them are reminiscent of the prehistoric cave paintings found in France and Spain. Some depict animals with unusual colorations. No one is sure why Bushmen often drew animals using the wrong colors. "Perhaps the Bushmen was limited as to available pigments," wrote Alfred Friendly of the Washington Post, "Often, however, he had a most variegated palette. One Bushman slain in [Lesotho] about 1866, and the last known painter of his band, was found to have ten small pots of animal horn slung around his belt. Each pot contained a different color."

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, who spent a great deal of time studying Bushmen, once gave the Bushmen some paper and paints. At first only the children would draw, but later the adults joined in, and everyone was laughing and having a good time. Many of their animals and figures resembled those found in cave painting. The only difference was that some of them looked like they were seen from above.

Sevilla rock art

Bushman Art Human Figures

The Bushmen drew more human figures than their Stone Age counterparts in France and Spain, but their figures never had faces or individualized forms. The Stone Age paintings in France and Spain are generally more dramatic and sophisticated.

The sex and hairstyles of the human figures depicted in Bushman paintings is clearly defined and many have patterns which are believed to have magical, religious or ceremonial purposes. Present-day bushmen have forgotten how to make the painting and interpret them. [Source: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

The Bushmen paintings depict figures playing reed flutes, escaping from ambushing leopards and dressed in knee-length cloaks. A figure in one cave had hooves instead of feet. In another they had heads and skins of buffalo. Anthropologists speculate these images might carry a religious message.

Purpose of the Bushman Paintings

Bushmen artists frequently drew over paintings that were already there. Some shelters have pictures with overlays, three or four deep. Some anthropologists suggest that for Bushmen artists "the act of painting was sometimes more important than the result."

Archeologists theorize that paintings had magical significance, and have argued that a depiction of a subject might put a curse on that subject. The Bushmen's Bantu enemies were easily recognized; they were painted big and black (the Bushmen painted themselves little and red) and they often carried clubs and shields, and had apelike faces.

"His paintings, " wrote South African writer Laurens van Van der Post, " show him clearly to be illuminated with spirit; the lamp may have been antique, but the oil is authentic and timeless, the flame was well and tenderly lit. Indeed, his capacity for love shows up like fire on a hill at night. He, alone of all the races in Africa, was so much of its earth and innermost being that he tried constantly to glorify it by adorning its stones and decorating its rocks with paintings. We other races went through Africa like locusts devouring and stripping the land for what we could get out of it. The Bushman was there solely because he belonged to it."

Game Pass shaman at work

Game Pass

Geoffrey Blundell of the University of the Witwatersrand wrote: “High in a secluded valley in the Drakensberg Mountains is the spectacular site of Game Pass. Here, on the walls of a narrow sandstone shelter, are painted a great many images of eland (the largest of all antelopes). For a shelter so open to the elements, the paintings are miraculously well preserved and in some places the brush marks can still be seen. Situated among the many images of eland are smaller human figures in running postures. This site, however, is most famous for a cluster of images tucked away on one side of the shelter. It was extensive analysis of these images that first led scholars to the realization that the art was a system of metaphors closely associated with San shamanistic religion. [Source: Geoffrey Blundell, Origins Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2001 \^/]

“This cluster of images is comprised of an eland with closely associated anthropomorphic figures. The eland's head is lowered, turned toward the viewer with staring hollow eyes. Its one front leg bends under its weight, while its two back legs are crossed over as it stumbles, and the hair on its neck and dewlap is erect. This sort of behavior is characteristic of eland when they have been wounded by one of the poisoned arrows that the San use to hunt. They stumble about, their heads sway loosely from side to side, they sweat profusely and even bleed from the mouth and nose, and the hair along their neck and back stands erect. This image, then, is of an eland in its final death throes. \^/

“Behind the eland, a human figure holds the tail of the animal; this figure's legs are also crossed, mimicking those of the eland's back legs. This human figure's legs continue all the way underneath the rock shelf, and close inspection reveals that the figure does not have feet but antelope hooves. Next to this figure are two more in similar pigment. The first is of a human figure bending forward with one arm stretched out behind its back. It apparently has no head—although the pigment may have worn away—and a short skin-cloak, known as a kaross, falls from the chest. Just above and to the right of this figure is one with an animal head, wearing a full kaross. To the right, in an orange pigment, is another human figure with an arm behind its back. This figure too, like the one clutching the eland's tail, has antelope hooves instead of feet and its hairs are erect like those on the eland itself. The arms-back posture—adopted by contemporary San at dances in the Kalahari Desert of Namibia and Botswana when they ask God to infuse them with supernatural energy—is frequently depicted in San art. Bending forward is closely related to the arms-back position and is adopted by dancers when the supernatural energy begins to "boil" in their stomachs. These three human-animal figures suggest a close association between the dying eland and the ecstatic experience of dancers. \^/

“Indeed, in the Kalahari, the San often like to perform a trance dance around or near the carcass of a freshly killed eland in order to harness supernatural energy (known as n/om) from the animal. When they have harnessed this energy, they enter an altered state of consciousness in which they stumble about, sweat profusely, and the hair on their bodies stands on end. So closely are the experiences of trance and the death of eland in their physical manifestation that the San talk about trance as "the death that kills us all." They speak of their experience metaphorically; for them, there is no difference between death and trance. \^/

“The link between the dying eland and the human figure clutching its tail in this cluster of images is a graphic metaphor—an allusion to the close parallels between death and trance. Once this metaphor was identified at this site, a new vista opened up for scholars, and many other religious metaphors and symbols were identified in San art. It is for this reason that the site is often referred to as the Rosetta Stone of southern African rock art.

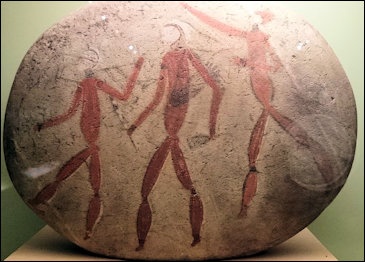

Coldstream Stone

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “This small polychrome stone, found buried with a human skeleton near the Lottering River in the southern part of the Western Cape province of South Africa, is famous not only for its great age but also its beautiful and unusually well-preserved imagery. Three figures with white faces and vibrantly elongated ocher bodies stride across this round stone's surface. [Source: Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, \^/]

“Documentations of South African Khoisan religious and trance practices recorded in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have been used to interpret not only more recent rock art but also rock paintings and engravings thousands of years old. Southern African rock paintings and engravings often combine geometric forms with images of humans and animals, in what some scholars have argued represents hallucinatory trance imagery. Although the Coldstream Stone itself does not contain references to animals or geometric patterns, some scholars have interpreted it in terms of Khoisan trance practices because of the nasal hemorrhaging of some of the figures. \^/

Apollo 11 (ca. 25,500–23,500 B.C.) and Wonderwerk (ca. 8000 B.C.) Cave Stones

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The earliest history of rock painting and engraving arts in Africa is uncertain. Increasing archaeological research in Africa demonstrates that many sites remain to be discovered. In addition, artworks on exposed rock walls are vulnerable to damaging weather and harsh climates, and although many do survive, only tentative steps have been made toward direct dating techniques. [Source: Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2000, \^/]

Apollo 11 stone slab

“Much more easily datable are painted and engraved rocks that have been buried deliberately, or that have fallen off the wall and become submerged in soil. Radio-carbon dating provides an estimate of when these rocks were buried, although it is still not possible to determine how old the images were before burial. \^/

“The seven slabs of rock with traces of animal figures that were found in the Apollo 11 Cave in the Huns Mountains of southwestern Namibia have been dated with unusual precision for ancient rock art. Originally brought to the site from elsewhere, the stones were painted in charcoal, ocher, and white. Until recently, the Apollo 11 stones were the oldest known artwork of any kind from the African continent. More recent discoveries of incised ocher date back almost as far as 100,000 B.C., making Africa home to the oldest images in the world. \^/

“Incised stones found at the Wonderwerk Cave in the Northern Cape province of South Africa suggest that rock engraving has also had a long history on the continent. The stones, engraved with geometric line designs and representations of animals, have been dated to circa 8200 B.C. and are among the earliest recorded African stone engravings. \^/

Central African Rock Art

Geoffrey Blundell of the University of the Witwatersrand wrote: “Of the three zones, the art of Central Africa is the least studied and least well understood. This zone stretches from the Zambezi River to below the Sahara Desert. The art differs significantly from that to the south and to the north in that images of animals and human beings do not predominate. Instead, the art is principally comprised of finger-painted, monochromatic geometric images. Because of the finger-painted geometric images, some scholars are investigating the link between the central zone and the Khoi art of the southern zone. [Source: Geoffrey Blundell, Origins Centre, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org, October 2001, \^/]

“There is one anomaly in the central zone—the art of the Kondoa region in central Tanzania. Although very faded with age, the art in this region is not finger painted but, like the fine-line southern African images, is also brush painted. In subject matter and style, it is more closely related to southern African San painting—and, in particular, that of Zimbabwe—than to any of the images in the central zone. It is believed that this enigmatic body of art is closely related to the Hadza and Sandawe people who, until recently, were still involved in hunting and gathering.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024