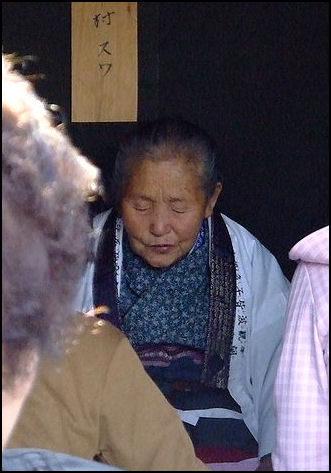

ITAKO SHAMAN OF JAPAN

Itako shaman There are still shaman in Japan.. Itako are shaman or mediums that have traditionally been blind or sight impaired old women that were called upon by bereaved family members to communicate with the dead. They embrace folk religion and animist traditions but also call upon Buddhist and Shinto gods for help. Each itako has her own gods that she calls upon. Some use aids such as beads and stringed bows to call the gods.

Itako have traditionally been looked down upon as little more than beggars. They were persecuted in the Meiji period and they sought refuge in remote places. They often dress in ragged clothes. When other people saw them they threw horse dung at them.

Itako were once common throughout Japan. According to one researcher there may have been 1 million of them roaming the countryside, working as mediums and healers, 150 years ago. They usually traveled with yamabushi (See Buddhism). Only about 20 or so itako remain, they are mostly in Aomori.

Onmyoji are traditional shaman trained in Taoist, Buddhist and Shinto magic. They are sometimes called on to perform exorcisms, which are done by convincing the spirits they should leave rather than forcing them out.

One itako told the Daily Yomiuri that when she was a child her poor eyesight kept her from attending school and “people thought I was strange because I said strange things.” She started to became aware of her itako powers when she discovered she could predict future events, such as natural disasters and accidents that would affect people and was able to find things people lost.

Itako train as an apprentice for five to seven years and then go through an initiation and series of tough endurance tests. The itako above began learning scripture by ear when she was a teenager from an itako master and stopped eating meat and eggs. She became an itako at the age of 18.

See Separate Article Itako Shaman factsanddetails.com; ANIMISM, SHAMANISM AND TRADITIONAL RELIGION factsanddetails.com; SHAMANISM IN SIBERIA AND RUSSIA factsanddetails.com; SHAMANISM AND FOLK RELIGION IN MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

Korean Shaman

Shamanism is Korea's oldest indigenous belief system. Originating from the North, it is still widely practiced in villages and even cities, especially during times of ritual transition and crisis. Shamanist rituals are performed on mountaintops, at traditional shrines or in village homes. Traditional Korean shaman religions that existed before the introduction of Buddhism include “Ch'ordogyoisn” and “Taejonggyo” , both of which are still practiced today. Ancient kings in the Shilla Dynasty were regarded as shaman as well political rulers.

Korean Hyewon-Munyeo Shamanism has experienced a rebirth in recent years more as an expression of nationalism and culture than religion. Most shaman are women. Shamanistic rituals are widely performed before ticket-buying audiences. Many shaman are women. Often their spiritual power is so great that they have to be separated from society in some way.

About 40,000 shaman are still active in Korea today. The are called “mudang” or “manshin” (literally "ten thousand spirits," a reference t number of spirits they can summon) and their rituals are known as “kut” . Nearly all of them are women who become shaman after being possessed by a spirit or god during a life-threatening illness. To maintain their rapport with gods they do things like rub rosary beads, consults old texts, and take cold shower, even in the winter time.

One shaman told the New York Times that she became a shaman after to being chronically sick beginning at the age of 43. "I went to hospital, but they couldn't cure me," she said. "I felt something bottled up inside me, and I couldn't get it out." She tried Christianity for three years and then went through initiation rites at the age of 49. "Ever since then," she said, "we've been happier and we've been making money."

Koreans often visit shaman if they are inexplicable sick, have marriage problems or need help producing children. Shaman charge about $2,000 for a ritual dance and usually require that the money be paid up front. At least until the last few decades the majority of villages in South Korea had shamans. Because villagers have often grown up with shaman in their village and sometimes doubt they really possess spiritual powers, they usually visit a shaman in another village if they need help.

See Separate Article SHAMANISM AND SPIRITS IS KOREA factsanddetails.com

Shamanism in China

Ancient historical texts described shamanist rituals in southern China in the forth century B.C. that honored mountain and river goddesses and local heros with erotic ceremonies that climaxed with fornication with the gods. The following poem describes such a ritual, performed by men and women shaman, who wore colorful clothes and doused themselves in perfume: Strike the bells until the bell-stand rocks! Let the flutes sound! Blow the pan-pipes! See, the priestess, how skilled and lovely! Whirling and dipping like birds in flight... I aim my long arrow and shoot the Wolf of heaven; I seize the Dipper to ladle cinnamon wine. Then holding my reins I plunge down to my setting.

According to a 4th century B.C. Chinese text "Discourses of the State", "Ancient men and spirits did not intermingle. At that time there were certain persons who were so perspicacious, single-minded and reverential that their understanding enabled them to make meaningful collation of what lies above and below and their insight [enabled them] to illuminate what is distant and profound Therefore the spirits would descend into them."

"The possessors of such power were, if men call “xi”, and if women, “wu”," the text continued. "It is they who supervised the positions of the spirits at the ceremonies, sacrificed to them, and otherwise handled religious matters...as a consequence the spheres of the divine and the profane were kept distinct. The spirits sent down blessing on the people, an accepted from them offerings. There were no natural calamities."

You can still find shaman today in China. Reporting from Xi Wuqi city in Inner Mongolia, Jonathan Kaiman wrote in The Guardian, “Erdemt is a 54-year-old former herder (who, like many Mongolians, only goes by one name), and as a shaman, he is considered an intermediary between the human and spiritual worlds. Although he is new to the role – he became a shaman in 2009 – thousands of people, all of them ethnically Mongolian, have visited so that he could decipher nightmares, proffer moral guidance and cure mysterious ills. His patients pay him as much as they wish.[Source: Jonathan Kaiman, The Guardian, September 23, 2013 ^^^]

See Separate Article SHAMANISM AND EXORCISMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Miao Religion and Spirits

The Miao are a colorful and culturally- and historically-rich ethnic minority that lives primarily in southern China, Laos, Burma, northern Vietnam, and Thailand. Originally from China, the Miao are animists and ancestor worshipers and have traditionally lived in villages located at 3,000 to 6,000 feet. The Miao are known in Southeast Asia as the Hmong (pronounced mung).

The Miao (also known as the Hmong) are animists, shamanists and ancestor worshipers whose beliefs have been shaped somewhat by Chinese religions, namely Taoism and Buddhism, and, more recently in the case of some groups, Christianity. Within a house there are special altars for the spirits of sickness and wealth in the bedroom, the front room, and loft and near the house post and the two hearths.

Male household leaders are usually in charge of the domestic worship of ancestor spirits and household gods. Part time specialist act as priests, diviners and shaman. They don special clothes when the preside over rites and employ chants, prayers and songs they have memorized. They are paid in food for their services. Shaman are generally called upon on cure illnesses by bringing back lost souls. They play a key role in funeral rites and are called upon to explain misfortunes and preside over rites that protect households and villages.

Miao spirits, known as tlan, are thought to live in high concentrations in places like sacred groves, caves, stones, wells and bridges. Household ancestor spirits (dab) are distinguished from spirts called up by shaman (neeb). The spirts that protect homes and villages are sometimes thought of as dragons.

The Miao pantheon of gods and spirits include Saub, a beneficent deity often invoked for help; Siv Yis, the first shaman; and the two malevolent underworld kings, Ntxwj Nying and Nyuj Vaj Tuam Teem.

Some Miao groups believe in a pre-eminent spirit that presides over all earth spirits; some do not. A few believe in a kind of cargo cult in which Jesus will arrive in a jeep and military fatigues and bring all kinds of wonderful things.

See Separate Article MIAO MINORITY: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

Dong Religion and Healers

Oroqen shaman costume The Dong are related to Thais and Lao and live primarily in the hills along the border of Hunan, Guizhou and Guangxi provinces in China. A 1990 census counted 2,514,000 Dong in China. They have their own language, Kam, a Sino-Tibetan tongue, and had no written language until the Communist government gave them one after 1949. [Source: Amy Tan, National Geographic, May 2008]

The Dong believe in spirits, ghosts and supernatural being such as the ganjin, a gremlin-like creature that has backward feet and lives in the mountains and is blamed for causing illnesses and trouble. When a child gets sick offerings of rice, chicken eggs, wine and anyu fish paste are made to ganjin to leave the sick child’s body.

Ceremonies and healing rites are often conducted by village feng shui masters, who have learned their trade from a senior family members and serve as herbalists and village doctors. Feng shui masters often receive patients in their kitchen may see a half dozen to a dozen people an hour. Describing a feng shui master at work in the village of Dimen, Amy Tan wrote in National Geographic, “One woman reported that her grandson had developed sudden pains in the head and stomach. The herbalist burned paper and floated ash in water with rice grains. He said an incantation counted on his fingers the names of gods who might have answers — God of Kitchen, God of Bridges, God of Injury, The diagnosis came back, The boy had seen the ghost of his great-grandmother. As a remedy the woman should make the great-grandmother a feast of rice wine and anyu, then invite her to eat week before the journey to the world of Yin, the underworld.”

“Another patient woke up with a stabbing pain in her throat,” Tan wrote. “The herbalist told her she was inhabited by the ghost of a man who had been hanged. A woman whose body hurt all over was inhabited but an ancestor who was unhappy that he never had a tombstone these past 200 years.”Prepare the anyu and bow. I’ll come tonight, and the ghost will be gone.” For a baby with diarrhea caused by drinking unboiled water he headed to a hillock, where he picked various leaves and long grasses to make a potion.

“He charged nothing for his healing services. But his grateful patients gave small gifts, an egg, some rice. He argued with one woman, who tried to give him two kwai, about 2 cents, for a rice fortune that would tell her future.” Most of the feng master’s patients are old people. A singing teacher in her 20s told Tan, “It’s superstition. It’s just old people who believe in ghosts.” Patients that go to clinics are inevitably given IV drips for whatever is wrong, whether it be a hacking cough, a stomach ache. If that doesn’t worker they visit the feng shui master.

See Separate Article DONG MINORITY: THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Yi Religion

The Yi are one the largest minority groups in China and the largest group in southwest China. They are uplands farmers and herders who live mostly in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces in the areas of the Greater and Lesser Liangshan mountain ranges at elevations of between 2000 meters and 3500 meters. They are particularly associated with the Hong River and Xiaoliang Mountains in Yunnan and the Daliang Mountains in Sichuan.

The Yi are also known as the Axi, Lolo, Loulou, Misaba, Nosu and Sani. The 1990 census counted 6,572,000 Yi in China. About 3 million live in Yunnan and 1.3 million live in Liangshin Li Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan. Another 560,00 live in Guizhou. There are also significant numbers in Guangxi.

Tiger man The have traditionally honored a pantheon of spirits and gods — including ones representing animals, plants, the sun, the moon and the stars — and incorporated elements of Buddhism and Taoism into their spiritual belief system. Sacrifices have been made to ancestors and ghost have been placated. According to the Yi creation myth: “In the beginning there was only women.” Protestant and Catholic missionaries had some success converted the Yi in the early 20th century and some of these communities remain alive today.

Yi shaman are known as bimo. Highly respected, they carry out sacrifices and perform healing rituals with incense and bowls of chicken blood. Headmen are responsible for controlling ghosts with magic. Often bimo were the only ones who could read the sacred texts that included clan histories, myths and literature.

The dead are believed to travel to another world where they can continue their lives. Special care is taken to placate the dead to make sure they don’t become malevolent ghosts. The Yi of Liangshan, Sichuan cremate their dead.

The chicken is an important totemic animal to the Yi. It is honored in a special dance performed at night by dozens of people wearing hats with strung beads arranged in the shape of chicken combs. To the accompaniment of a moon guitars, the dancers execute fast tempo steps from the knee down that mimic the movements of a chicken.

See Separate Article YI MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

Lisu Religion

.jpg)

Last Oroqen shaman in July 1994 The Lisus, along with the Hmong, have traditionally been one of the Golden Triangle's largest opium-producing tribes. They are a fairly large ethnic minority that lives in southwest China, northern Thailand, northern Laos, eastern Myanmar and northeast India. Traditionally slash and burn farmers, they reside in villages widely scattered among other groups and are regarded as one of the most colorful ethnic minorities in Southeast Asia.

The Lisu have traditionally believed in a spirts associated with natural phenomena and deceased human beings. Great care was taken not to offend the spirits thought to have the power to cause illness and bring misfortune. Each village has its own primary spirit. Divinations with pig livers, chicken femurs and bamboo dice were traditionally performed before important activities such building a house or embarking on a hunting trip.

Most traditional villages have a priest who is chosen through divinations. He keeps track of events scheduled by the lunar calendar and presides over rituals. Some villages have a shaman. His primary responsibility is contacting deceased ancestors and spirits to seek their help to cure the sick. In a typical healing ceremony a shaman goes into a trance, invokes the spirt associated with the disease the person is suffering from and calls on the family of the sick to sacrifice a pig or chicken.

At funerals, prayers are recited and ritual offerings are made with the aim of speeding the soul on its journey to the next world. Those who died in violent deaths or accidents are given exorcisms. The Lisu believe the spirit of dead person is potentially dangerous for three years. Ancestor spirits are honored with regular offerings of rice liquor, joss sticks and ragweed.

See Separate Article LISU MINORITY: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor worship involves the belief that the dead live on as spirits and that it is the responsibility of their family members and descendants to make sure that are well taken care of. If they are not they may come back and cause trouble to those family members and descendants.

Unhappy dead ancestors are greatly feared and every effort is made to make sure they are comfortable in the afterlife. Accidents and illnesses are often attributed to deeds performed by the dead and cures are often attempts to placate them. In some societies, people go out of their way to be nice to one another, especially older people, out of fear of the nasty things they might do when they die.

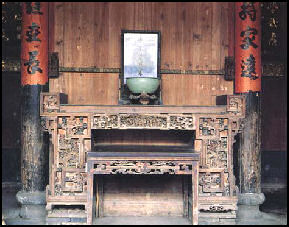

Home ancestor altar in Fujian, China Some people attribute poor weather to unhappy ancestors, so prayers are said and special ceremonies are performed so the dead will use their influence to bring good weather and enough rain to produce a good harvest. Sometimes property is still believed to be in the procession of dead ancestors, and before a piece of property or a family possession is sold, the dead are consulted through special ceremonies.

Ancestor worship is perhaps the world's oldest religion. Some anthropologists theorize that it grew out of belief in some societies that dead people still exist in some form because they appear in dreams.

Ancestor worship is a strong cohesive force in primitive societies and one of the most widespread beliefs in primitive religions. Customs and traditions are passed down orally, without written records, there is no sense of history as we know it, and often myth and fact from the past become inseparable.

Ancestor Worship in China

Ancestor worship is very deeply rooted in China and still very much alive today. Ancestors are generally honored and appeased with daily and seasonal offerings and rituals. It has been said spirituality emanates from the family not a church or temple.

Pictures of dead relatives are featured on family alters in many Chinese homes, where religious rituals and prayers are regularly performed. Candles are regularly lit and offerings are made at ancestral shrines and graves, which are often visited during holidays. One Chinese man told AFP that the Chinese "believe their ancestors are still watching them, unlike the Western Christian belief that their ancestors go to heaven and that's the end of it."

Offerings to ancestors Ancestor worship goes back deep into Chinese history. More than 5,000 years ago, the cultures of northern China were venerating the dead through highly systemized ceremonies. Echoes of these traditions still survive today. Peter Hessler wrote in National Geographic, “In ancient times the dead functioned in an extensive bureaucracy. Royal names were changed after death to mark the transition to new roles. The purpose of ancestor worship was not to remember the way people had been in life. Instead, it was about currying favor with the departed, who'd been given distinct responsibilities. Many oracle-bone inscriptions request that an ancestor make an offering of his own to an even higher power. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, January 2010]

“In a culture as rich and ancient as China's, the line from past to present is never perfectly straight, and countless influences have shaped and shifted the Chinese view of the afterlife. Some Taoist philosophers didn't believe in life after death, but Buddhism, which began to influence Chinese thought in the second century A.D., introduced concepts of rebirth after death. Ideas of eternal reward and punishment also filtered in from Buddhism and Christianity.

See Separate Article ANCESTOR WORSHIP IN CHINA: ITS HISTORY AND RITES ASSOCIATED WITH IT factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012