ECSTASY

MDMA crystal Ecstasy (or simply "E") is the street name for a euphoric stimulant with mild hallucinogenic effects called MDMA (the abbreviation for 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine). MDMA is a synthetic drug that alters mood and perception (awareness of surrounding objects and conditions). It is chemically similar to both stimulants and hallucinogens, producing feelings of increased energy, pleasure, emotional warmth, and distorted sensory and time perception. There are estimated to be 20 million “ecstasy” users globally..Global Seizures in 2019 were 16 tons, an increase of 38 percent from 2018. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC); U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)]

MDMA has been described as an entactogen — a drug that can increase self-awareness and empathy. Researchers have determined that many ecstasy tablets contain not only MDMA at different concentrations, but also a number of other drugs or drug combinations that can be harmful. Adulterants found in ecstasy tablets purchased on the street have included methamphetamine, the anesthetic ketamine, caffeine, the diet drug ephedrine, the over-the-counter cough suppressant dextromethorphan, heroin, phencyclidine (PCP), and cocaine. [Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2017]

According to the United States' Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in its 2001 report 'Ecstasy: Rolling Across Europe',“80 percent of the world's ecstasy is produced in clandestine laboratories in The Netherlands and, to a lesser extent, Belgium”. Some operators in Belgium and the Netherlands appear to have started to also manufacture methamphetamine, a drug for which the demand seems to have increased in 2020.

See Separate Article ECSTASY: HISTORY, USE, EFFECTS AND HOW IT WORKS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) justice.gov/dea/concern ; Vaults of Erowid erowid.org ; United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) unodc.org ; Wikipedia article on illegal drug trade Wikipedia ; Frank’s A-to-Z on Drugs talktofrank.com ; Streetdrugs.org streetdrugs.org ; Illegal Drugs, country by country listing, CIA cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook

Books: “Buzzed" by Cynthia Kuhn Ph.D. Scott Swartzwelder, Ph.D., Wilkie Wilson Ph.D. of the Duke University Medical Center (Norton, 2003); “Consuming Habits: Drugs in Anthropology and History" by Goodman, Sharratt and Lovejoy; “Drug War Heresies: Learning from Other Vices, Times and Places" by Robert MacCoun and Peter Reuter (Cambridge University Press).

Ecstacy Production and Supply

Netherlands and Belgium are believed to be the two largest producers of ecstasy and amphetamines in Europe. Spain, Poland, Romania and other countries in eastern Europe have also been producers.

According to the UNODC: “Ecstasy” manufacture takes place in all regions but remains concentrated in Europe A total of 18 countries reported the dismantling of more than 340 “ecstasy” laboratories in the period 2015–2019, while 36 countries were identified as countries of origin of seized quantities of the drug. Nonetheless, “ecstasy” continues to be manufactured primarily in Europe, most notably in Western and Central Europe. Europe accounted for 58 percent of the “ecstasy” laboratories dismantled worldwide in the period 2015–2019, followed by Oceania (19 percent), the Americas (12 percent) and Asia (11 percent). The ongoing concentration of “ecstasy” manufacture in Europe seems to be linked to the ability of the operators of such laboratories to employ a high degree of chemical expertise, innovation and flexibility in overcoming shortages in the supply of traditional precursors by identifying new, alternative substances that can be easily imported and used as pre-precursors. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

Although eight European countries reported the dismantling of “ecstasy” laboratories in the period 2015–2019, including countries in Western and Central Europe and in Eastern Europe, the number of both “ecstasy” laboratories dismantled and reports of source countries of the drug continue to point to Belgium and the Netherlands as the countries where most “ecstasy” manufacture takes place in Europe.

The dismantling of “ecstasy” laboratories has been reported in both North America (Canada and the United States) and Latin America (most notably Argentina and Brazil and, to a lesser extent, the Dominican Republic) in the period 2015–2019. This suggests that “ecstasy” is no longer exclusively imported into Latin America. In Asia, the largest number of dismantled “ecstasy” laboratories was reported by Malaysia, followed by Indonesia. In Oceania, most of the “ecstasy” laboratories dismantled were in Australia. In Africa, the dismantling of “ecstasy” laboratories to date has been limited to South Africa.

Ecstasy Labs

Ecstasy lab in Jakarta Unlike amphetamines, ecstasy is relatively hard to make and requires sophisticated chemical and pharmaceutical knowledge and equipment to make it.

Ecstasy tablets have contained the images of Donald Duck, Batman, Queen Elizabeth, Princess Diana, and the Flintstone's Dino as well as four-leaf clovers, horseshoes, the Nike symbol, the Yin-yang symbol, the Mercedes symbol and candy canes. In the late 1990s, Mitsubishis were especially popular.

In the late 1990s, about 80 percent of the world’s ecstasy was produced in clandestine urban and rural laboratories in the Netherlands. Along the Dutch-Belgian border a number of labs were set up in abandoned barns and garden sheds, where chemicals were sometimes mixed in filthy cans. The cost of producing a single pill is about $.10.

In the early 2000s, ecstasy tablets were manufactured in makeshift mobile labs set up inside large trucks or floating barges. Many were run by Israeli gangsters. Dutch officials tried to shut down the labs but said they were "overwhelmed" by the extent of the problem.

Ecstasy Sales and Distribution

Ecstasy sells for about $20 to $50 a hit on the street and at raves and clubs. According to the United Nations annual report on drugs, issued in June 2009, global production of stimulants — namely methamphetamines and ecstasy — rose in 2008.

The Netherlands is also a major distribution point. It funnels ecstasy produced in Eastern Europe to points in Europe. MDMA seized in the United States is primarily synthesized in Canada and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands. There are a small number of illegal MDMA labs operating in the United States.

For a while In the 1990s and 2000s, much of the ecstasy in Europe and the United States is distributed by Israeli and Russian organized crime. Egyptians, Syrians and Koreans are also reportedly involved in the trade. Many of the Israelis in the trade are Russian émigrés with prior convictions for cocaine and heroin smuggling. Many are also involved in diamond smuggling from Antwerp, which has traditionally been the turf of the Russian mafia.

Couriers to the United States have included Hasidic Jews, middle-class Texas families and Los Angeles strippers. Young Hasidic Jews, recruited because they were believed to arouse little suspicion by customs inspectors, reportedly have been given $1,500 each for carrying 30,000 to 45,000 pills in their suitcases. One major ring has used Federal Express to ship large amounts of ecstasy from Amsterdam to places in Europe via Korea, France and Mexico.

According to the UNODC: Over the period 2015– 2019, besides supply from within the subregion (Canada and the United States), supply from a number of countries in Western and Central Europe (Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands) was also reported. In 2019, United States authorities reported that close to 70 percent of the “ecstasy” found on the domestic market had originated in the Netherlands and almost 30 percent in Germany; about 98 percent of the “ecstasy” had entered the United States by mail and 2 percent by land (mainly trafficked from Canada).

“Ecstasy” trafficking from Canada to the United States appears to have declined in recent years, while shipments of “ecstasy” from Europe (where laboratory operators have successfully experimented with the use of alternative pre-precursors) to North America have increased. It seems that these transactions are increasingly being carried out by Asian organized crime groups located in the United States, who often purchase the “ecstasy” from Asian organized crime groups based in Europe. However, the increase in recent years of “fake” “ecstasy” tablets containing other substances than MDMA on the United States market suggests that there could be an ongoing shortage of MDMA on that market. In fact, data from twelfth-grade high-school students in the United States suggest that the availability of “ecstasy” has declined in recent years, from 37.1 percent reporting that it was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to obtain the substance in 2015 to 23.5 percent in 2019, a far larger decrease than for any other drug.

Regional distribution of the quantities of “ecstasy” seized, 2015–2019: A) Western and Central Europe: 24 percent; B) North America: 21 percent; C) Oceania 20 percent; D) South-Eastern Europe: 17 percent; E) Asia: 12 percent; F) Other Americas: 3 percent; G) Africa: 2 percent; H) Eastern Europe: 1 percent.

Trends in Ecstasy Production and Trafficking

According to the UNODC: Increase in trafficking in “ecstasy” over the period 2011–2019 A number of indicators, including the number of “ecstasy” laboratories dismantled, the number of “ecstasy” seizure cases, the quantities of “ecstasy” seized and reported trends in trafficking in “ecstasy” on the basis of qualitative information, showed a clear upward trend in the supply of the drug between 2011 and although this upward trend appears to have reversed in 2020 as a consequence of the restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

“Ecstasy” manufactured in regions other than Europe seems to be mostly intended for use within the region where it is manufactured, although there are exceptions. Countries in Oceania report not only imports from Europe and local manufacture of “ecstasy” but also shipments from countries in Asia (notably China and Israel in the period 2015–2019). However, in the fiscal year 2018/19 in Australia, the 10 most common embarkation countries for “ecstasy” shipments were all located in Europe. Intercepted shipments of “ecstasy” in Australia mainly involved shipments by mail (98 percent); by weight, air cargo accounted for the greatest proportion of detections (48 percent), followed by international mail (28 percent).

Another exception seems to be “ecstasy” manufactured in North America, which is also reported as a source of supply in Asia, although less frequently (5 percent of all mentions of countries of origin and departure over the 2015–2019 period) than imports from Europe (51 percent) and local manufacture in Asia (39 percent). In Asia, the most commonly reported countries of origin and departure of “ecstasy” were the Netherlands, followed by Malaysia. The most commonly mentioned source country in North America was the United States.

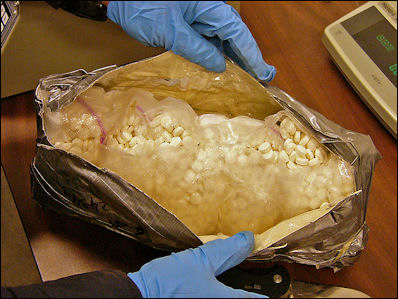

Seized Ecstasy In contrast to most other drugs, there seems to be two-way trafficking in “ecstasy”, from East and Southeast Asia to North America, but also from North America to Asia, most notably to East and Southeast Asia. For a long time, “ecstasy” trafficking in North America primarily involved Asian organized crime groups located in Canada, working together with Asian organized crime groups located in the United States. MDMA was either imported from East and Southeast Asia into Canada or manufactured in Canada from precursor chemicals obtained from East and Southeast Asia, and then smuggled into the United States.

The quantity of “ecstasy” seized at the global level almost quadrupled after the low in 2011 to reach 16 tons in 2019, the second-highest level ever reported. There has been a marked increase in the quantity of “ecstasy” seized in almost all regions since 2011. In Europe, “ecstasy” seizures quadrupled, to reach 7 tons in 2019, in parallel with signs of an ongoing expansion of the “ecstasy” market, including increasing use of “ecstasy” pre-precursors in the manufacture of the drug in the region, a decline in “ecstasy” prices and a very sharp increase in the MDMA content of “ecstasy” tablets since the second half of the 2000s. The average MDMA content of tablets more than doubled over the past decade in European Union countries to reach 132–181 mg (interquartile range) per tablet in 2018, with very large amounts of MDMA (up to 409 mg) found in some batches of the drug in 2018, resulting in an increase in the potential harm linked to the use of “ecstasy”. Overall, 101 countries reported seizures of “ecstasy” in the period 2015–2019, up from 71 countries in the period 1995–1999, suggesting a clear geographical expansion of trafficking in “ecstasy” over the past two decades.

Analysis of individual seizures show substantial “ecstasy” trafficking in Europe but also in Southeast Asia, the Americas and Australia. In contrast to many other drugs, where one country often continues to dominate global seizures over a prolonged period, the situation seems to change quite frequently in the case of “ecstasy”. For example, the largest quantities of “ecstasy” seized in 2014, 2016 and 2017 were reported by Australia, in 2018 by Turkey and in 2015 and 2019 by the United States. European countries still dominate “ecstasy” seizures, however. Among the 15 countries reporting seizing the largest quantities of “ecstasy” in 2019, 9 were located in Europe.

Efforts to Crack Down on Ecstasy Production

Most of the chemical used to make Ecstasy are controlled by international law. The Europe Commission has aimed to disrupt the drug manufacturing business by placing more restrictions on chemicals that can be used to make Ecstasy, amphetamines and LSD. They also have tried to expand present drug laws to cover new synthetic drugs that appear on the market. As of the 2000s, it took two to three years for a new drug to become outlawed. Unlike heroin, cannabis and cocaine, which all originate from field plants, amphetamine and ecstasy production can not be monitored by satellites because it takes place in garages, shacks and small factories that can not be easily identified.

Eline Schaart wrote in Politico, “Producers can get round such measures by slightly altering their chemical makeup, meaning authorities then have to restart the long legal process to get the new substance listed. Alternatively, the producers can re-create the listed substance from pre-precursors. Local police don't always have the capacity to follow up on a case, and even if they do manage to catch the people dumping the waste red-handed, the drug bosses usually remain beyond their reach. [Source: Eline Schaart, Politico, July 22, 2019]

Ecstacy Precursors

According to the UNODC: Manufacture of “ecstasy” is on the increase and increasingly based on non-controlled pre-precursors The long-term upward trend in the global supply of “ecstasy” in the 1980s and 1990s gave way to a (temporary) downward trend in the second half of the first decade of the new millennium, prompted by a shortage of traditional “ecstasy” precursor chemicals on the market (most notably 3,4-MDP-2-P), which was mainly due to improved precursor control at the global level, and in China in particular. This changed after 2011, when operators of laboratories succeeded in identifying alternative chemical precursors. A number of indicators have shown a clear upward trend in the supply of the drug since 2011; and several countries reported that the MDMA content of “ecstasy” tablets was higher in 2019 (over 100 mg of MDMA per tablet) than it had been a decade prior, which also points to a likely increase in the availability of “ecstasy”. The latest information shows that traffickers continue the search for innovative solutions for accessible precursors. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

Following the placing under international control in 2019 of two “ecstasy” pre-precursors, 3,4-MDP-2-P methyl glycidate and 3,4-MDP-2-P methyl glycid acid,264 their presence on the market drastically reduced (as evidenced by the large decrease in the amount of them seized), while other potential alternatives have emerged.In 2019, there was an increase in the number of reports and in the geographical spread of the use of helional, an alternative pre-precursor for the manufacture of MDA and MDMA.

Nonetheless, it seems unlikely that the substances mentioned above, at least in the short term, will be able to compensate for the reduction in the supply of the well-established “designer precursors” 3,4-MDP-2-P methyl glycidate and 3,4-MDP-2-P methyl glycid acid resulting from their international control in 2019, suggesting that the global manufacture of “ecstasy” may have started to decline after its peak in 2019.

Even though helional has been encountered since 2011 in the manufacture of “ecstasy” in a number of countries, including Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States, its use has now also spread to other countries. For example, in 2019, Brazil reported seizures of almost 220 kilograms of helional in two clandestine laboratories involved in the synthesis of MDA. Seizures of methylamine, which is used in the manufacture of “ecstasy”, methamphetamine and synthetic cathinones, were reported in 2019 by the Netherlands (more than 4.3 tons), Mexico (more than 2,600 litres) and Viet Nam (70 litres), although the seizures in the last two countries seem to have been related to the manufacture of methamphetamine rather than “ecstasy”. In recent years, countries in North America also reported seizures of formaldehyde and ammonium chloride, substances that were seemingly intended to be used in the clandestine manufacture of methylamine in order to manufacture methamphetamine.

Is It Really Ecstacy in Those Ecstacy Tablets?

According to the UNODC: “Ecstasy” is a term that was originally used to describe tablets containing MDMA.However, an increasing number of different substances or products marketed as “ecstasy” have appeared on the markets in the past two decades.From the mid- to late 2000s, owing in particular to the declining availability of and controls placed on the precursors used to manufacture MDMA, the tablets sold as “ecstasy” in the various markets contained ever decreasing quantities of MDMA as the active ingredient and showed increasing adulteration, as well as substitution with other psychoactive substances. [Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), World Drug Report 2021]

As a result over the years “ecstasy” tablets containing little or no MDMA, and containing any of its analogues (including MDA and MDEA), substituted with other chemicals such as PMA or PMMA, or containing NPS (including 2C-B or piperazines), were reported, although not necessarily in all markets at the same time.While those diverse “ecstasy” products have persisted in different markets, since 2010/11, “ecstasy” products with a high MDMA content have gradually re-emerged, especially in the European market, as well as elsewhere. For example, in Europe tablets with an average of 125 mg of MDMA have been reported (although they also contain binding agents), compared with the 50–80 mg of MDMA reported in the 1990s and 2000s. The forms of “ecstasy” have also diversified; it may also be sold in powder form as finely ground MDMA crystals, with other substances added, and in a crystal form that may contain MDMA in the purest form.

In the European drug markets, for instance, MDMA crystal, powder and tablets can be found side by side in the market, sometimes as competing products. Notwithstanding the diversity of “ecstasy” products, they are still commonly referred to as “ecstasy” in many parts of the world; however, in some reports in Europe, such products are categorized as MDMA. It is difficult to determine which of the “ecstasy” products are predominantly used in a subregion. Nevertheless, in the following sections the term “ecstasy” has been used to describe the use of “ecstasy” or MDMA-type products in the different regions.

Production of Ecstasy in the Netherlands

Netherlands is as a major production country for the ecstasy. In 2008, the U.N. reported that 42 percent of the ecstasy seized worldwide originated in the Netherlands. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) also recognized that seized batches were primary produced in clandestine laboratories in the Netherlands and Belgium. Because the Netherlands is considered a source country, the Dutch government has taken an active role in detecting production sites and devising countermeasures. Much of the production and trafficking is controlled by organized crime groups.[Source: Melvin R. J. Soudijn, Landelijke Eenheid and M F J Vijlbrief, “Routledge Handbook of International Criminology, pp.248-259, Chapter: 24, Routledge, January 2011]

Synthetic drugs — primarily ecstasy and amphetamines — with a street value of ($22 billion) were produced in the Netherlands in 2017, according to the report by the Police Academy in the Dutch city of Apeldoorn. Out of that total, an estimated $2.5 billion to $4.5 billion billion remained in the hands of Dutch producers, authorities said. [Source: DW, August 25, 2018]

In 2017, 21 active ecstasy laboratories were dismantled in the EU, up from 11 in 2016 — and all of them were in the Netherlands, according to a report released by the EU drugs agency in June, 2019. Dutch drugs production added up to 614 million grams of amphetamine and 972 million ecstasy pills in 2017. Most of these illicit substances are produced for export: Around 80 percent ends up elsewhere in Europe, in Southeast Asia and Australia. [Source: Eline Schaart, Politico, July 22, 2019]

DW reported: The report by Police Academy in Apeldoorn underscored that its figures were only estimates, saying that the actual numbers are likely to be much higher. Researchers and authorities attribute the country's position as a top drug producer to a combination of factors, including the Netherlands' tolerant approach towards drug use as well as its relatively low penalties for those caught making the drugs. The country's good infrastructure and location in Europe also makes it a hub for producing and transporting the illegal substances.

The police report also criticized the government's response to combating illegal drugs, saying that information available on synthetic drugs is "woefully inadequate." "Anti-drug efforts only receive priority when friendly heads of state (the US, France) raise the alarm about the drug industry in the Netherlands," the report stated, adding that the "effect of this outside pressure is also relatively short-lived."

North Brabant: Home of Many Dutch Drug Labs

North Brabant, a Dutch province close to the Belgian border, is Europe's biggest producer of synthetic drugs, such as ecstasy and amphetamine.“ Many of the drug labs dismantled by police in the Netherlands have been here. In North Brabant an ecstasy pill costs $2.30; in Australia its around $30. There’s a massive profit margin on these drugs.” Willem-Jan Uijtdehage, spokesman for the local police, told Politico.[Source: Eline Schaart, Politico, July 22, 2019]

Eline Schaart wrote in Politico, North Brabant is an ideal location, according to Uijtdehage of the local police, with the ports of Antwerp, Rotterdam and Vlissingen handy for global exports and the Belgian border nearby. But forest ranger de Jong believes there's a local characteristic among the local people that also makes North Brabant such a popular location for producing illegal drugs: "There's a mentality of looking the other way, averting your gaze when it comes to your neighbors," he said.

In May, a police raid on a floating crystal meth laboratory in Moerdijk was literally scuppered after the 85-meter boat — containing methamphetamine oil with a street value of more than €4.5 million — suddenly began to sink. Police believe it was a remotely operated attempt to destroy evidence.

Environmental Damage from Drug Labs in the Netherlands

Reporting from Bergen op Zoom, Netherlands, Eline Schaart wrote in Politico: “Next to the train tracks, down a winding dirt road, lie piles of black garbage bags and empty jerrycans... Forest ranger Erik de Jong spotted the dump on his daily rounds. He's not surprised. In 16 years' work in North Brabant, the 36-year-old ranger has found countless such garbage sites related to the production of illicit drugs in the area. "When I started working in this area these findings were still occasional, maybe once or twice a year. But now there are times when it's my full-time job, with sometimes up to 10 findings a week," he said. [Source: Eline Schaart, Politico, July 22, 2019]

“The long list of ingredients for synthetic drugs includes acetone, formic acid and hydrochloric acid, while producing just 1 kilogram results in an average 18-24 liters of waste, depending on the type of drug and process. Local government experts estimate the annual volume of waste from illicit drug production is about 255,000 kilograms per year. Most of it is dumped in the countryside, resulting in 109 reported findings in 2018, up from 83 in 2017.

“Over the years, the producers have found innovative ways to dispose of waste: in the car wash, in manure — resulting in traces of speed and ecstasy found in corn — or from a driving car, leaving trails up to 9 kilometers long. The consequences for people, animals and the landscape are serious: Waste acid wreaks havoc in the sewage system and residues can be dangerous not just via direct contact, but also via the groundwater.

The economic damage is also considerable: The removal and processing of drug waste and contaminated soil costs tens of thousands of euros. In Baarle-Nassau, a water treatment plant had to be shut down twice because of major drug discharges, and the clean up cost between €80,000 and €100,000 each time.

Is the Netherlands a 'Narco-State'

Eline Schaart wrote in Politico, The Dutch synthetic drugs industry was born in the late '60s with amphetamine and moved into ecstasy in the mid-'80s, supported by technical expertise that lent a reputation for reliability and safety to the "made in Holland" brand.In the wider Dutch context, the illicit drugs trade benefits from a strong criminal network. Indeed, a 2018 report from the Dutch police union said the Netherlands "fulfils many characteristics of a narco-state" — one where public institutions are vulnerable to penetration by influence and money from drug mafias. "Only one in nine criminal groups can be tackled with the current people and resources," the report said. "Detectives see small criminals developing into wealthy entrepreneurs who establish themselves in the hospitality industry, housing market, small businesses, travel agencies." [Source: Eline Schaart, Politico, July 22, 2019]

Justice Minister Ferdinand Grapperhaus presented a package of new measures in July 2019 to fight the drug trade, including a proposed watchlist of chemicals whose possession, transport, import and export would be subject to a maximum prison sentence of six years. He also wants to recoup the costs of destroying seized drugs from convicted criminals. But for MP Maarten Groothuizen, justice spokesman for the center-left D66 party which belongs the four-party ruling coalition along with Grapperhaus' Christian Democrats, the proposals are mainly symbolic. "In most cases no one is arrested, so this has a symbolic value," he said.

Groothuizen said he understands the need to tackle trade in the raw materials, but questioned whether it would really help. "It's a very complex issue, but we must seek to regulate this type of drugs on an EU-level in a different way from the one we are currently seeking through criminal law," he said, hinting at the Dutch gedoogbeleid (“tolerance policy”) that's already in place for the sale of cannabis in coffee shops and for prostitution.

Image Source: DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration)

Text Sources: 1) “Buzzed, the Straight Facts About the Most Used and Abused Drugs from Alcohol to Ecstasy” by Cynthia Kuhn, Ph.D., Scott Swartzwelder Ph.D., Wilkie Wilson Ph.D., Duke University Medical Center (W.W. Norton, New York, 2003); 2) National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 3) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and 4) National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, The Independent, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, , Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2022