BIRD BEHAVIOR

Birds preen, bathe and go through a lot of efforts to stay clean. They will even try to keep their feet from getting dirty. When no water is available they take dust bathes or expose themselves to sunlight. All birds bathe and usually follow their bathes with drying, shaking or scratching, feather-smoothing and using their bill to massage oil from a preening gland into their roughed up feathers. Cleaning and preening are necessary to keep plumage healthy. Research has shown that 30 percent of the flying done by birds is done for fun.

Many birds sleep at night. When they are sleeping, half of a bird's brain sleeps while half remains alert. This might explain why many birds sleep with one eye open. Some birds can sleep while flying. Some protect themselves from snakes by fluffing up their feathers so that a striking snake would only get a mouthful of feathers.

The Austrian naturalist Konrad Lorenz was the first person to describe how the young of some species of birds have a psychological mechanism in their brains that impels them to follow the first large moving object they see after the hatch from their eggs. Lorenz called the process "imprinting." Imprinting has been observed in geese, rails, coots and most famously with ducks. With the mallard ducking the process is very precise: taking place between 13 and 16 hours after the ducking hatches. In almost all cases the first large objects the young see is their mother but Lorenz showed that birds deprived of their mother would follow him.

Marc Lallanilla of NBC News wrote: Birds' ability to learn from their environment is a constant source of surprise for researchers. Scientists have discovered, for example, that crows will use stones as tools to raise the water level in a pitcher and snatch a worm floating on the water (just like the clever crow in Aesop's famous fable). And birds that have a bad experience with humans (such as being trapped and banded for wildlife studies) will remember those particular people's faces — and will teach their friends which humans are the "bad humans," even years after an unpleasant encounter. [Source: Marc Lallanilla, NBC News, August 25, 2013]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BIRDS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, COLORS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD FLIGHT: FEATHERS, WINGS, AERODYNAMICS factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Resources on Birds: ; Essays on Various Topics Related to Birds stanford.edu/group/stanfordbird ; Avibase avibase.bsc-eoc.org ; Avian Web avianweb.com/birdspecies ; Bird.com birds.com ; Birdlife International birdlife.org ; National Audubon Society birds.audubon.org ; Cornell Lab of Ornithology birds.cornell.edu ; Ornithology ornithology.com ; Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Fraud and Mimicry Among Birds

In his book, “The Liars of Nature and the Nature of Liars”, Lixing Sun, a professor of animal behavior and biology at Central Washington University, addresses fraud and cheating in the animal — and human — world. Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: One way that animals cheat, in Sun’s schema, is by issuing false information, or, more plainly, by lying. Many animals (and even plants) communicate with one another; this is often a critical survival skill. But the possibility of communication inevitably opens up the possibility of miscommunication. Crows, for example, issue alarm calls to alert other crows to potential danger. Conniving corvids, according to Sun, “cry wolf” to scare their neighbors from food. [Source Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, March 27, 2023]

Consider the case of the superb fairy wren, a small, sweet-looking bird native to Australia. Horsfield’s bronze cuckoos—also small and sweet-looking—frequently parasitize fairy wrens’ nests. Fairy-wren moms, it seems, have come up with a musical defense: they sing a special tune to their chicks while they’re still in their shells. The mother birds repeat the tune until their chicks are ready to hatch, which is around the time when the bronze cuckoos swoop down to deposit their eggs. Once the fairy-wren chicks emerge, they incorporate the notes their mother has taught them into their begging call. The cuckoo chicks, either ignorant of the melodic password or unable to mimic it, get fed less, or sometimes not at all.

Bird Sounds

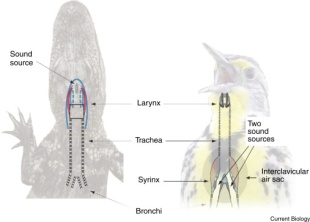

Birds produce vocal sounds in a similar way to humans except they use a syrinx, a box-shaped organ surrounded by rings of cartilage, rather than a larynx. Running between the syrinx and the lungs are tubes. Noises and songs are produced by fleshy lip that control the air flow into the syrinx and vibrating muscles within the syrinx that control pitch and note quality.

Birds have a larynx but it does not produce sound. It prevents food and water from entering its windpipe and lungs. The bird larynx is located at the base of the windpipe (trachea) as opposed to the top where mammals make their sounds.

To make sounds birds push air out of their lungs through the syringeal muscles, which the bird can squeeze almost shut until they vibrate like a trumpeter's lips. These vibrations produce sound waves that travel from the base of the birds windpipe to its mouth. Bigger birds generally have bigger tracheas and a deeper timbre to their voices.

Young birds often go through a babbling stage similar to of human infants as they learn to make notes and produce songs. Their brains are wired so that they learn songs of their species and ignore other songs the same way babies learn to speak by listening to people and shutting out noises from cars and dishwashers.

Bird Chirping

According to the Chinese Academy of Sciences: The cries of birds can be classified into two types, i.e. “chirping” and “singing”. Birds' chirping is rather simple but it means a lot. Birds chirp to indicate danger, warning and communication. Both male and female birds can chirp. The singing of birds is quite sweet and agreeable, often with a melodious tone. In most case, male birds will sing in mating seasons. It's the signal of a male bird to seek for spouse after occupying a territory. [Source: Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn]

It’s quite interesting to listen to the chirping of birds. Attention must be paid to the syllables and changes of the chirping when listening. People should judge whether the chirping is in single syllable or in plural syllables whether it is in a continuously repeated tone or in varied tones and whether it is rather course or is refined. People should also judge whether the chirping is like whistling or the friction sound of metals? If the chirping of birds is accompanied with concords, it will be more beneficial for people to recognize and to memorize them.

The chirping of cuckoo is like “bugu” the chirping of hawk cuckoo is like“beibeilou” or“cuiguya” small cuckoo's chirping is like“youqian dajiu hehe”, while the chirping of Flycatcher and Grey-headed canary flycatcher sounds like“qingqing xiuxiu”. Attention should also be paid to the reaction of birds while listening to their chirping. So to speak, the chirping for their communication can let all birds of the same kind gather together while the warning chirping will make the birds disband and fly away in no time. If you often observe their chirping, you’ll get to know their language and become an expert in understanding birds.

Bird Songs

Bird produce a variety of sounds for a variety of reasons. Most are believed to be associated with courtship, defining territory, sounding alarms, calling other birds, and distinguishing friendly neighbors form potentially hostile strangers. Some species have difficulty identifying their own kind by sight but can easily identify them by their song. In temperate areas the best time to hear birds is in the spring and summer during the morning.

Studies indicate that birds don’t just make random trills and noises but produce what can arguably be called music. They often make the same acoustic and aesthetic choices and abide by the same rules of composition that human musicians and composers do. Birds use notes, rhythmic variations, harmonic patterns and pitch relationships found in human music and musical phrases of a similar length. Some thrushes sing in the so-called pentatonic scale, in which octaves are divided into five notes, which is the basis of music, including rock n' roll, found in many human cultures.

Males songbird often sing to let other males know that a particular territory belongs to them. Their courting songs are among the most complex songs. Many of these have traditionally been thought to be linked to the male demonstrating his ability to the female to provide food and fight predators but songs themselves have no link to any such purpose. Studies show that bird with the most complex songs often get the girl but as soon as they get the girl the singing stops. Among many species, though, females need a song cue from their mate to begin producing eggs and building a nest.

The number os songs that a particular species can sing varies quite a bit. A woodpecker may sing just three songs; a thrush, 50. A thrasher can sing more tan 2,000. In at least 200 species of birds, males and females sing "tightly-scripted duets throughout their relationship.” As a rule the bird with the most beautiful and sophisticated songs are unremarkable looking while the bird with most beautiful feathers and displays have the most unremarkable songs.

Book: “ Why Birds Sing” by David Rothenberg (Basic Books, 2006)

Bird Babbling and Communication

Research by a team at MIT lead by Michael Fee published in the May 2008 edition of Science found that baby zebra fiches “babble” before they learn to sing their adult songs. “Birds start out babbling, just as humans do,” Fee told AP, while the adult bird produces a very precise pattern. With the finches the babbling took place during a 30 to 35 day period. The study also found that different parts of the brain controlled babbling and singing. Scientists were excited about the findings in that it offered insights into how language develops in humans and other animals.

Scientists have long wondered whether duets were the result of a pair birds singing together or an effort by two birds to avoid interfering with one another. A study of dueting Peruvian antbirds published in Current Biology by Joseph A. Tobias and Bathalue Seddon of Oxford University suggests it may be little of both with a pair singing together most of the time but the female occasionally attempting to jam the male’s song by singing over it. The findings were made by exposing antbird pairs to recorded songs of other antbirds and monitoring how they responded. When a tape of an intruding pair was played both the male and female cooperated to send out a message to stay away but when the song of a single female was splayed the male flirted while the female tried to drown out his song.

Some birds are very loud and pushy. According to Smithsonian.com: When they’re feeling frisky, male white bellbirds (Procnias albus) sidle up to a female, inhale deeply and scream directly into her face. Their calls are the loudest ever recorded in the avian world, peaking at roughly 115 decibels, the approximate equivalent of shoving your head into “a speaker at a rock concert,” researchers have said. While belting out multi-note ballads, the males will strut around and whip their wattles (fleshy outgrowths that dangle over their beaks) so vigorously that they sometimes slap their dates in the face. [Source: Katherine J. Wu , Rachael Lallensack, Smithsonianmag.com, February 14, 2020]

“Females don’t seem to mind the punishment. In fact, researchers suspect they’re pretty into the whole mess — an attraction that’s driven the evolution of such an extreme, possibly even deafening, trait. Perhaps the shrieks are the males’ way of boasting their physical prowess. Or maybe these boisterous boys just don’t know when to shut up — and the ladies know not to expect any less.

Bird Sex

About 90 percent of bird species are monogamous. Many times the male defends a territory with a sufficient food supply for his mate and their young. Male birds often have more flashy plumage than females. This may be at least partly because females need camouflage when they are nesting.

Birds copulate very quickly. Some species even copulate while they in the air. And male birds don't have a penis. Scientists speculate the reason for this may be a penis would weigh to much or interfere with standing or flying or engaging in a lengthy copulation would make the vulnerable to attacks for predators.

Both males and females posses a single rear vent called cloaca, which is connected to their sexual organs and their digestive tracts. During sex, both the male and female turn their cloacae inside out and place them end to end. Sperm from the male's sperms sacs travel through a duct and is transferred within seconds to the female's oviducts. It usually take some time for the sperm to travel up the oviduct and unite with the an egg. The sperm may remain alive in oviduct for days, even weeks.

David Attenborough wrote: "The actual mechanics of mating used by birds is clumsy. The male...has to mount rather precariously on the female's back, steadying himself by clinging onto her head feathers with his beak. She twists her tail to one side so that the two vents are brought together and the sperm, with a certain amount of muscle assistance from both partners is transferred to the female....The female has to remain very still or he topples off."

About 90 percent of bird species form pair bonds to breed. But some are not always faithful and will even pay for sex. Male great gray shrikes — elegant raptor-like birds with silver capes, white bellies and black tails — usually presents his mate with rodents, lizards, small birds and large insects that may be impaled on a stick. When seeking extra-marital sex he will offer a bigger kebab with even more goodies. Shrikes are also known for issuing alarm calls to warn one another of predators but also for issuing false alarms to drive other shrikes away.

Flocking Birds

A flock that moves as a group in one direction can form as birds begin to orient themselves more strongly with other birds in the group. It is believed that some birds hang out in flocks because members of the group can alert others if there is predator or other danger in the area. They also flock for social reasons.

Flocks of birds are effective at maintaining the well being of the flock. A flocking group is able to monitor a large area; gather information of what is there; relay the information to others and respond collectively to dangers and opportunities.

To examine the flocking behavior of birds, Craig Reynolds, a computer graphics researcher, created a seemingly simple steering program in 1986 called boids that helps demonstrate how flocking works. In the program generic birdlike objects, or boids, follow three simple rules: 1) avoid crowding nearby boids; 2) fly in the general direction of nearby boids, and 3) stay close to nearby boids. The result: convincing simulations of flocking behavior, including lifelike and unpredictable movements. The concept has been used to simulate swarming behavior in Hollywood movies, Sony video games and groups of small robots.

Studies by Iain Cousin at Oxford University found that a large group — say a flock of migrating birds — can head to a desired direction with only a couple of individuals knowing the way and each member of the group having two instincts; 1) staying with the group; and 2) moving in a desired direction. Two leaders may try to pull the flock in different direction but the flock tends to stay together.

Couzin told the New York Times, “As we increased the difference of opinion between the informed individuals, the groups would spontaneously come to a consensus and move in the direction chosen by the majority. They can make these decisions without mathematics or even recognizing each other or knowing that decision has been made.”

Website: Flock Patterns: red3d.com

Migrating Birds

Every year billions of birds migrate between summering areas, where they nest and breed, and wintering areas where they feed and escape the escape the cold. They travel to the wintering areas in the autumn, navigating through fog, night skies and sometimes long expanses of ocean and desert and return in the spring. When choosing their time to migrate, birds seem to respond to cues such as lengthening or shortening amounts of daylight. The birds that arrive first often get their pick of the best feeding and nesting areas.

Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: “If, like me, you live in North America and don’t know much about ornithology, you probably associate those migrations with a jagged V of Canada geese overhead, their half-rowdy, half-plaintive calls signalling the arrival of fall and spring. As migrants go, though, those geese are not particularly representative; they travel by day, in intergenerational flocks, with the youngest birds learning the route from their elders. By contrast, most migratory birds travel at night, on their own, in accordance with a private itinerary. At the peak of migration season, more than a million of them might pass overhead every hour after dark, yet they are no more a part of a flock than you are when driving alone in your S.U.V. on I-95 during Thanksgiving weekend. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

“The stories of these avian travellers are told in abundance in Scott Weidensaul’s “A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds.” An ardent ornithologist, Weidensaul sometimes shares a few too many details about a few too many species, but one sympathizes: virtually every bird in the book does book-worthy things. Consider the bar-headed goose, which migrates every year from central Asia to lowland India, at elevations that rival those of commercial airplanes; in 1953, when Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary made the first ascent of Mt. Everest, a member of their team looked up from the slopes and watched bar-headed geese fly over the summit. Or consider the Arctic tern, which has a taste for the poles that would put even Shackleton to shame; it lays its eggs in the Far North but winters on the Antarctic coast, yielding annual travels that can exceed fifty thousand miles. That makes the four-thousand-mile migration of the rufous hummingbird seem unimpressive by comparison, until you realize that this particular commuter weighs only around a tenth of an ounce. The astonishment isn’t just that a bird that size can complete such a voyage, trade winds and thunderstorms be damned; it’s that so minuscule a physiology can contain a sufficiently powerful G.P.S. to keep it on course.

Some birds migrate several thousand miles. The fly over deserts, tundra and mountain ranges and rely on wetlands along the way to rest and replenish themselves. Often they will take a more circuitous route over land than a more direct route over the sea to gain access to wetlands and feeding spots. Species of songbirds may divide into new species when different subopulations decide to take different migration routes. European backcaps, for example, are divided into two major subpopulations, each with its own migratory pattern. Members of the subpopopualtes tend to only mate with their own kind. Over time they could develop into new species.

Bar-Tailed Godwits — Birds That Fly Nonstop Between Alaska and New Zealand

Every year in September and October bar-tailed godwits fly 11,265 kilometers (7,000 miles) from Alaska to New Zealand — the longest nonstop migration of a land bird in the world— to breed and raise its young. They travel eight to ten days without eating, drinking or resting along the way.Jim Robbins wrote in the New York Times: Tens of thousands of bar-tailed godwits are taking advantage of favorable winds for their annual migration from the mud flats and muskeg of southern Alaska, south across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, to the beaches of New Zealand and eastern Australia.“The more I learn, the more amazing I find them,” said Theunis Piersma, a professor of global flyway ecology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and an expert in the endurance physiology of migratory birds. “They are a total evolutionary success.” [Source: Jim Robbins, New York Times, September 20, 2022]

The godwit’s epic flight through pounding rain, high winds and other perils is so extreme, and so far beyond what researchers knew about long-distance bird migration, that it has required new investigations. In a 2022 paper, a group of researchers said the arduous journeys challenge “underlying assumptions of bird physiology, orientation, and behavior,” and listed 11 questions posed by such migrations. Dr. Piersma called the pursuit of answers to these questions “the new ornithology.”The extraordinary nature of what bar-tailed and other migrating birds accomplish has been revealed in the last 15 years or so with improvements to tracking technology, which has given researchers the ability to follow individual birds in real time and in a detailed way along the full length of their journey. “You know where a bird is almost to the meter, you know how high it is, you know what it’s doing, you know its wing-beat frequency,” Dr. Piersma said. “It’s opened a whole new world.

The known distance record for a godwit migration is 13,000 kilometers, or nearly 8,080 miles. It was set last year by an adult male bar-tailed godwit with a tag code of 4BBRW that encountered inclement weather on his way to New Zealand and veered off course to a more distant landing in Australia. He had flapped his wings for 237 hours without stopping when he touched down. The globe-trotting birds are in search of an endless summer, and some 90,000 or so depart Alaska from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and environs, where they breed and raise their young. Both Alaska and New Zealand are rich in foods that godwits like, especially the insects in Alaska for newly hatched chicks. And New Zealand has no predatory falcons, while Alaska offers secure habitat.

See Separate Article: BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Human Obstacles to Bird Migrations

Every year tens of thousands of migrating birds are killed when they fly into buildings. Many are attracted by light or of fly into windows after seeing reflections of things such as trees. In New York City and Chicago more than 32,000 birds from 147 species have died this way.

The migration patterns of some birds already seems to be disrupted by global warming. Populations of pied flycatchers, for example, a bird that nests in Europe and winters in Africa, are shrinking because caterpillars that parents traditionally fed to their young are appearing earlier because of warming temperatures and past their peak in numbers when the flycatchers fed them to their young. Fewer young birds are surviving because they don’t get enough to eat.

Abraham Rinquist wrote in Listverse: Poachers in Cyprus are decimating the songbird population. Their hunting technique is simple and ancient. They use lime sticks covered in ultra-sticky gum derived from Syrian plums. The sticks are placed in the inviting lower branches of juniper trees. Foraging birds become ensnared. The quarry of the traditional Cypriot bird hunters is blackcaps, a common European wren considered an island delicacy. The problem with the gum-stick technique is that there is tremendous by-catch of endangered species—like the spotted flycatcher. There are many organizations and volunteers working to stop the songbird slaughter. The challenge is daunting. Bird hunting is an ancient part of Cypriot culture and there is no shortage of poachers. The lime sticks do tremendous damage to the birds. They are often fatally wounded in the rescue process. [Source: Abraham Rinquist, Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Studying Migrating Birds

Surprising little is known about the migrating habits of birds. Many patterns are thought to have evolved in the last 10,000 years because many places where birds spend the summer were under ice before that.

Scientist attempt to study migrating habits of birds by banding them. If someone finds a bird they are supposed to notify the contact imprinted on the band. A bird found in Ireland, for example, may have been banded and have a contact in Austria. The recovery rate of these bands is very poor. Of 450,000 pied flycatchers banded in their summering areas in Europe during a 60 year period fewer than five were recaptured in their wintering area.

Transmitters that send signals to satellites are too large for most birds. Tags placed on large sea birds, however, have recorded levels of ambient lights that can be translated into longitude and latitude and picked up by satellites. Sometimes birds are captured and kept in enclosures with ink on their feet. The direction the birds migrate is gauged by checking direction the birds want to fly based on the ink marks they leave behind.

Some scientists study whether birds winter or nest in southern or northern latitudes based on the amount of deuterium (the “heavy hydrogen” isotope) in their bodies. Deuterium is more prevalent on water supplies in northen latitudes. Migrations of large numbers of birds can be tracked with radar and satellites.

Using very small geolocaters, which weigh as little as paper clips and can be attached to even small birds, scientists have been able to track the migration of songbirds such as wood thrushes and purple martins for the first time. The scientist were surprised to find out how far the birds could fly. Some species traveled 480 kilometers a day, much further and faster than the 145 kilometers that had previously been estimated. Some purple martins that spend the winters in the Amazon, left Brazil in mid April and were back in North United States by the end of the month. Scientists had previously thought they must have left at least as early as March. The research was carried out by a team lead by Bridget Stutchbury, a professor of biology at the York University in Toronto.

The geolocators are small plastic devises that weigh 1.5 grams and record sunrise and sunset. They are placed in small backpacks that are fitted on the birds. When the birds are recaptured the times of the sunrises and sunset gives the location of the bird at each recording. In 2007 the devices were placed in 14 wood thrushes and 20 purples martins. In 2008 the geolocaters were retrieved on five wood thrushes and two purple martins. The wood thrushes wintered in Nicaragua and Honduras. The purple martins wintered in the Amazon, During the migration the birds rested for a few days in the southern United States and Mexico’s Yucatan area.

Migratory Birds Are Genetically-Programmed, Study Appears to Show

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The plan went something like this: Lash a Lilliputian knapsack to the back of a wild songbird called a Swainson’s thrush, release the bird to begin its grueling 8,000-mile round-trip migration, and then return a year later to the exact same spot in the vast Canadian forest to await the bird’s return and retrieve its miniature luggage, which holds a tracking device. “To our great surprise, we actually succeeded,” says Darren Irwin, a University of British Columbia ornithologist. His team, led by PhD student Kira Delmore, collected dozens of the devices as part of a study that provides the strongest evidence to date that certain genes govern avian migration patterns — and may also guide the mass movements of creatures from butterflies to wildebeests. [Source:Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, October 2016]

“It has long been an open question whether a migrating bird learns its complex flight path from other members of the flock, or, on the other wing, if the route is somehow encoded in its genes. Suspecting the latter, Delmore and the team, who published their findings in Current Biology, followed the Swainson’s thrush because the species is split into two subgroups that migrate along very different routes: Traveling south from British Columbia, one subgroup hugs the California coast and heads to Mexico, while the other veers over Alabama en route to Colombia. Every spring both return to Canada and — here’s the key — sometimes interbreed.

“Sorting through the tracking data, the researchers found that the hybrid offspring favored a flyway that was in between those of the two subspecies. Since the hybrid thrushes couldn’t have learned that middle road, it seems that the birds were guided by a mixture of genetic instructions inherited from both parents. To pinpoint the genes responsible, the researchers compared the DNA of parents and hybrids, zeroing in on a stretch that includes the “clock gene,” which is known to be related to circadian rhythms and believed to be involved in migration.

“The research promises big new insights into evolution. For instance, the hybrid thrushes’ flyway takes them over terrain where food may be scarcer than along the other two routes; if many end up starving to death, the hybrid subgroup may never get off the ground (so to speak), and the other two subspecies may become increasingly distinct until they split into separate species entirely. That would be evidence of a long-suspected but rarely observed phenomenon — genes that control behavior contributing to the origins of species. That process might take many years. But Irwin thinks the first clues are encoded in those little backpacks.

But instinct alone does not explain everything that migratory birds can do. Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: In 2006, scientists in Washington State trapped a group of white-crowned sparrows that had begun their annual migration from Canada to Mexico and transported them in a windowless compartment to New Jersey — the avian equivalent of the kidnapping thought experiment. Upon release, the juvenile birds — those making their first trip — headed south along the same bearing that they had been using back in Washington. But the adult birds flew west-southwest, correcting for a displacement that nothing in their evolutionary history could have anticipated. That finding is consistent with many others showing that birds become better navigators during their first long flight, in many cases learning entirely new and more efficient strategies. Subsequent experiments found that mature birds can be taken at least six thousand miles from their normal trajectory and still accurately reorient to their destination. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

How to Prevent Birds from Flying into Windows

According to the American Bird Conservancy, every year in the United States about 1 billion birds fly into glass and are killed. Alyse Messmer wrote in the Tacoma News Tribune: When birds see a window, they see a reflection of the sky or trees and believe its safe to fly towards, and according to The Humane Society of the United States, “at least half of the birds who hit windows die from their injuries or because another animal killed them while they were stunned and couldn’t escape or protect themselves,” its website states. [Source: Alyse Messmer, Tacoma News Tribune, March 15, 2022]

Here are five ways you can make your windows safer for birds and decrease the number of bird collisions this year: 1) Add a screen or a net outside your window, about 2”-3” away from the surface. This will allow the birds to bounce off of the window instead of hitting it. 2) Put decals on your window. Stores such as Amazon have a variety of window decals made to reflect light and deter birds from flying into the window. You can also paint designs on windows to help deter birds with soap or washable paints. Birds focus on the spaces between designs, so make sure not to space them too far apart.

3) Put strips of tape on your window, but be cautious of the spacing. The Humane Society suggests using tape strips outside the window, lined up vertically. If you use white tape, space the vertical strips four inches apart, and if you use black tape strips, spaced an inch apart. The spacing between the tape is important as if it’s too spread apart, birds may think they could fly between the tape strips. 4) Install external window shutters, awnings or shades. You can close the shades to get rid of the deceiving reflection of the window, or use an awning or shade to limit the reflection. 5) Install vertical blinds, not horizontal. Vertical blinds are better at deterring birds, especially when only open halfway or less.

According to the Humane Society, there are five things you can do to help a bird that has had a collision: 1) Gently handle the bird with a towel and put it in a cardboard box or paper bag with holes for air, but that is securely closed. 2) Keep the bird in a warm, dark quiet place. 3) Check on the bird in the box or bag every 30 minutes, but do not touch the bird. 4) If the bird is recovering, carefully take the bird outside and open the box or bag to see if it exits. If it does not, gently take the box back inside. 5) If the bird does not recover but is still breathing, contact a wildlife rehabilitator.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Mostly National Geographic articles. David Attenborough books, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2024