PRODUCTS FROM THE RAINFOREST

Cocona juice from

the Peruvian rain forest Items which can be harvested from the rainforest include chicle, used in making gum; latex, the main ingredient of rubber; allspice, which serves as both a spice and medicine; rattan, used for making baskets; and a number of key ingredients for medicines. Rainforests also produce a large variety of resins, tannins, steroids, waxes, bamboo, flavorings and dyes stuffs used to make consumer goods such as lubricants, glue, golf balls, nail varnish, deodorant, tooth paste, shampoos, mascara and lipstick.

Among the foods that originated in the rainforests and are still produced there are pineapples, bananas, citrus fruits, yams, cocoa, sago, cassava, heart-of-palm, avocado, papayas, mangos Brazil nuts, winged beans and several edible oils. Spices that come from rainforest plants are vanilla, nutmeg, cinnamon and black pepper. Some plants have multiple purposes. The South American babassu is being raised as a source of edible oil, margarine and shortening and ingredients for detergents, soap or plastics.

"One can only guess," journalist Peter White wrote in National Geographic, " at the number of new pharmaceuticals, fibers, vegetable oils and other materials waiting to be discovered." In the 1980s, scientists harvested protein from the wing base of insects that could tolerate bending far longer than any other material. One scientist told National Geographic: "This is just what I want for paint — wouldn't it be nice to have a paint you can stick over a door and it can bend with the hinge. Once we know its structural properties, we may build those insights into plastic, or whatever structure breaks down with continual flexing. There could be thousands of applications."

One of the tragedies of deforestation is that a managed forest yields a higher rate of income in perpetuity than a cleared parcel of land used for timber, ranching or agriculture. One study determined that a hectare of forest could yield $500 worth of fruit, nuts, latex, rattan and other products a year, for a total of $10,000 over 20 years, more than could be earned from the same plot over the same period by timber extracting, ranching or farming. The plot could be worth even more if medicinal plants and valuable oils are extracted..

Brazil nuts When the carbon storage capacity of the forest is factored in the value of the forest is even higher. The World Bank estimates that an acre of rain forest converted to crops is worth $100 to $250. It’s worth far more under a system that puts a value on carbon. An average acre stores about 200 tons of carbon; assuming a low price of $10 a ton, that acre is suddenly worth $2,000.

Websites and Resources: Rainforest Action Network ran.org ; Rainforest Foundation rainforestfoundation.org ; World Rainforest Movement wrm.org.uy ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Forest Peoples Programme forestpeoples.org ; Rainforest Alliance rainforest-alliance.org ; Nature Conservancy nature.org/rainforests ; National Geographic environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rainforest-profile ; Rainforest Photos rain-tree.com ; Rainforest Animals: Rainforest Animals rainforestanimals.net ; Mongabay.com mongabay.com ; Plants plants.usda.gov ;Books: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); “Portraits of the Rainforest” by Adrian Forsythe. National Geographic articles “Rainforest Canopy, the High Frontier” by Edward O. Wilson, December 1991 ▸; “Tropical Rainforests: Nature's Dwindling Treasures”, by Peter T. White, January 1983 ∩

See Separate Articles: TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS AND WEATHER factsanddetails.com; AMAZON: THE RIVER AND FOREST AND THEIR HISTORY AND ECOLOGY factsanddetails.com; STUDYING THE RAINFOREST: METHODS, TECHNOLOGIES AND HARD WORK factsanddetails.com PEOPLE IN THE RAINFOREST: INDIGENOUS TRIBES, SETTLERS AND SLASH-AND-BURN AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

Medicines from the Rainforest

quinine Tropical rainforests are the source of between 10 and 15 percent of the natural medicines prescribed today. Chemicals found in rainforest plants have been used for treating cancer, Hodgkin's disease, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis, and as an aid for surgery, and for the production of sex hormones. Scientist know the chemical composition of less than ten percent of the rainforest's plants.

Drugs from the rainforest include quinine (from the cinchona tree, used for treating malaria), ipecac (used make people vomit certain poisons), emetine (from a South American plant, used to cure amoebic dysentery); Tubocurarine and curare (muscle relaxants used in surgery, derived from poison frogs), resperine (from a Southeast Asia plant, use t o alleviate hypertension); picrtoxin (from the Levant berry of South and Southeast Asia, used to relieve convulsions and restore breathing after barbiturate overdose); Salagem (used to reduce the side effects of radiation treatment on cancer patents) and cocoa (cocaine).

Tea made from a kind of yam found in Mexico was used for birth control by rainforest women for hundreds of years. In the 1960s, drug companies discovered its potential and isolated and reproduced the active ingredient, diosgenin, giving birth to "the pill."

About 25 percent of the pharmaceutical drugs sold in the United States are derived from 40 plants, about and 40 percent of the all drugs sold are extracted from plants, animals, fungi and microorganisms. Drugs that come from plants include aspirin (from white willow bark), digitalis heart medication (from foxglove), and the cancer treatment taxol (from the Pacific yew tree). No doubt there are more out there to discovered. Only about 1 percent of the worlds 265,000 flowering plants have been examined for potential drugs.

Rainforest People and Medicines

Cinchona, source of quinine Indigenous people use rainforest plants for a number of folk medicines that scientist haven't even begun to explore yet. Some rainforest Indians employ plants that are purported to relieve arthritis and hepatitis and prevent pregnancy for two years with a single dose. Others use fungus solutions dripped through curved leaves to treat earaches and brew special teas that are said to instantly soothe queasy stomachs. If these indigenous people are lost or become to assimilated into the modern world we risk losing knowledge of medicines and plants that could benefit all fo mankind.

In their daily lives rainforest people, who often don’t have access to modern medicine, treat wasp stings with certain leaves, soothes burns with a red sap, get rid of skin fungus with crushed leaves, and "make you skinny" with juice extracted from a "sweet-smelling plant." In Africa, the shavings of Gracinia tree are used to treat diarrhea. In South America, leaves for one plant are chewed raw to reduce a fever and boiled and rubbed on the skin around snake bites. Another plant is brewed into tea for suppressing colds and coughs and berries are used to treat centipede bites. [Source: Donald Dale Jackson, Smithsonian magazine, February 1989]

Most medicines are taken from the roots, bark, leaves and saps of plants and then made into a "tea" or external poultice. To treat diabetes with the bark and fruit from a medium-size tree, South American shaman told Smithsonian magazine, "You take boiling water and put pieces of bark in it. You take a glass of it. It gives people the qualities of a tiger and makes them strong, very strong...If the patients with the disease aren't treated, they die."

Some rainforest medicines "cures" are probably little more than placebos and some remedies are down right preposterous. In some parts of South America, for example, headaches are "cured" by witch doctors who suck them out through their fist or stick a large bumblebee under the patients hat.

Scientists, Rainforest People and Medicines

palm leaf Scientists have investigated the use of vampire bat blood to dissolve blood clots; patented a scared Amazonian mushroom; examined pastes made from red seeds used by Irula tribes in India to treat cobra bites; studied frogs used by the Brazilian Yawanawa Indians to treat intestinal problems; and helped the Kani people in India market a energy-giving berry. There are even taking blood samples form certain tribes in the Philippines and Brazil and analyzing their DNA to develop gene therapy that take advantage of immunities these tribes have to diabetes and cancer.

Some of the rainforest chemicals that biologists and pharmacologists are interested in the most are toxins. These often hold the most promise for combating diseases because the toxins are often harmful to disease-causing viruses, bacteria and microorganisms. One plant used to treat rheumatism was picked out for investigation because its bark seem to ward of insects and fungi.

"Antidote plants" that often grow very close to poisonous plants are also studied. One shaman described in the Wall Street Journal showed the scientists a fern that has potential as a potent analgesic that grew near a species called the Devil's garden tree, which gives off a chemical that prevents other plants from flourishing. "The fact that the fern can overcome a chemical threat means it could have its own chemical arsenal,” one of the scientists said.

Scientist often are forced to make snap decisions in the field on which plant to study and which to ignore because investigating them can be so expensive. When the scientists followed by Smithsonian magazine was shown a plant used against headaches that also generated visions and made “it possible to see the future," he commenting "Hmm, that not so good," worrying about the potential side effects."

Some scientists investigating the use of herbal medicines by shamans try not to influence shamans by asking them directly about medicines. They converse about the weather, their children and approach the subject they are interested in a circular fashion. Describing scientists who use pictures, Thomas Burton, wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "The botanists show the medicine man photographs of patients with various symptoms, such as rashes and swelling of viral and fungal origin, yellow eyes associated with hepatitis, and foot sores typical of diabetes. They don't steer the shaman in any direction; they keep poker faces, betraying neither excitement or displeasure."

Mark Plotkin, Shaman's Apprentice

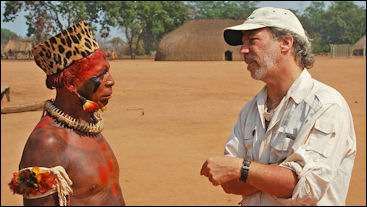

Mark Plotkin with Wauru chief Dr. Mark Plotkin, the author of “Tales of the Shaman's Apprentice” and “Medicine Quest: In Search of Nature's Hidden Cure”, is a major advocate for the belief that miracle medicines and marketable goods can be found in the rainforest. Plotkin's Amazon Conservation Team is supported by actress Susan Sarandon and Todd Oldham. [Source: Donald Dale Jackson, Smithsonian magazine, February 1989]

The son of a Jewish shoe salesman from New Orleans, Plotkin dropped out of the University of Pennsylvania's biology department because he was more interested in studying whole organisms rather than cells. Plotkin later studied at Yale and Tufts and worked at the Harvard Botanical Museum under Dr. Richard Evans Schultes, who inspired Plotkin and others with tales of Indian rituals and hallucinogenic potions. Plotkin began working with shaman in South America as part of his studies to be an ethnobotanist. His reputation grew when he was featured on the cover of Smithsonian magazine and was described as real life Indiana Jones and the Carl Sagan of the rainforest.

Plotkin has spent a great deal of time among in the Amazon rainforests among tribes such the Sikiyan-Chikena. In one of his books he described a Sikiyan-Chikena shaman who treated a woman who was near death with severe diabetes with concoctions made herbs and vine sap gathered from the forest. The morning after she took the concoction her blood sugar had returned to normal and within a few days she was healthy enough to return to work. "I was knocked over," Dr. Plotkin told the New York Times. "He literally raised that woman from the dead."

Book: “Tales of the Shaman's Apprentice” and “Medicine Quest: In Search of Nature's Hidden Cure” by Mark Plotkin.

Drug Companies and the Rainforest

Even though some scientists say the search for new drugs in the rainforest is "quixotic," and fueled by "naive, over-optimistic expectations," the major drug companies have offices in Iquitos, Peru and other Amazon cities, invested large amounts of money in research and very secretive about what they are doing.

Merck & CO. made a $1 million dollar deal with Coast Rica's National Institute of Biodiversity to screen plants, insects and micro-organisms for medicinal compounds. G.D. Searle & Co and Pfizer have similar arrangements with U.S. botanical gardens.

The drug companies primarily collect specimens and ship them to North American or European laboratories where they are analyzed and tested. One of the hot issues is whether drugs made from the rainforest can be patented.

Shaman Pharmaceutical

Shaman Pharmaceutical Inc. of San Francisco is company that believed it could turn a profit from medicine found in the rainforest. Even though it lost million in was unable to get any drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration, it attracted investments of $55 million, including $4 million from El Lily Co., in the early 1990s and developed two promising drugs — one for herpes and other for a childhood respiratory disease — in that made it to the clinical trials. Both drugs are derived from the South American croton tree, which is cultivated by shaman in the rainforest. [Thomas Burton, Wall Street Journal, July 7, 1994]

rattan furniture

Shaman Pharmaceutical has sent people to the rainforest in West Africa, Papua New Guinea, Ecuador and Peru to investigating plants with compounds that could be used to fight diabetes and viral and fungal infections and looking for an effective nonaddictive painkiller. Hundred of pounds of stems, roots, bark and berries collected are sent back to California for analysis in five-foot-long duffel bags. About 20 percent of the company’s budget is earmarked to help finance water, school and social welfare projects in exchange for knowledge about medicinal floras. The company gave one jungle community $5,000 to build an airstrip, new school and water system and provide it with doctors.

None of the drugs Shaman Pharmaceutical worked on panned out. By the late 1990s their stock had slid to practically nothing and the company announced it dropped its quest for new drugs from the rainforest and was concentrating dietary supplements." One scientist with the company told the New York Times, "The rhetoric ran away from reality. And the whole thing has backfired. We have not found new drugs. And the fact that the idea is deeply flawed was never questioned."

Yes, Indians have found effective treatments in the forest but many of the most promising plants have already been screened, beginning with Spanish conquistadors, and the ones that yielded medicines, such as quinine and curare, have already been exploited.

Perfume Companies in the Rainforest

Representatives from perfume companies, looking for new fragrances and scents, mostly from orchid,. are also in the rainforest. Employees of Givaudan Roure, a company that creates fragrances for perfumeries and other companies, has sent employees to the rainforest in French Guiana and hired rainforest scientists to assist in the search for new fragrances.

The scientist often check out flowers that attract moths because the scents that attract them and usually considered pleasant by humans. To take samples, the scientists use "head space" technology — equipment used by beer brewers to analyze the air above beer head and determine when fermentation process is complete — to trap the air and scent around a flower. The air is captured in a globe then directed through a cylinder of absorbent material called Tenax that is sealed when it is filled. The cylinders are taken to a lab and the gases are analyzed with a mass spectrometer.

Rattan

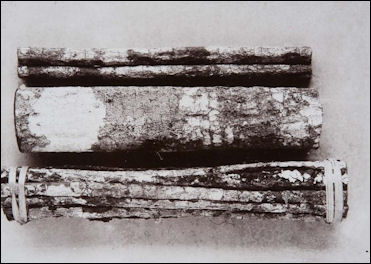

Rattans are climbing palms native to southeast Asian. The have tough and slender stems as thick as a man’s finger and tendrils with hooks sharp enough to rip a shirt or scrape skin. The hooks are used to attach to trees so the plants can climb upwards. In the forest they flourish as parasitic vines that cling to the forest with “multiple throned tentacles” hundreds of feet long.

rattan palm Rattan palms yield a fiber called, obviously enough, rattan that is prized for making furniture, baskets, mats, brushes, hampers, and even canes. The strongest and most valuable part of the vine is the skin. The fibers are covered with spines which are used for climbing up the trunks of trees.

Once a rattan establish itself on a tree it can climb to the top of the canopy and sprout huge palm-leaves that can block out the sun on its host plants. Rattans continue to grow vigorously even if their weight overwhelms branches and brings the host plants crashing to the ground. They can grow to length of over 500 feet, giving them longer stems than any other plant, and thereby, by some standards, making them the world’s longest plants. .

Like other palms, rattans are nearly always unbranched and grow only from the bud at their end. If something happens to the bud, the plant can die. The crown is often very tasty and animals like to eat it. Their sharp spines for protection.

Rattan palms have some very complicated relationships with other forms of life. The tips of some species of rattan are protected by small black ants that produce a loud hissing noise by banging their heads on dry husks when disturbed and mass together and viciously bite any intruders. In return the rattan provides the ants with a place to nest and raise aphids, which turn feed on sap in the rattan and in turn excrete a liquid called honey dew that the ants feed on. [Source: David Attenborough, The Private Life of Plants, Princeton University Press, 1995]

Uses and Kinds of Palms

There are several thousand species of palms. Valuable kinds of palm include coconut palms, date palms, sago palms, betel nut palms. Some palms produces a sweet sap that is made into candy, sugar and wine. The nuts of the tagua palm yields vegetable ivory. Carnauba palm leaves produce wax.

Palm tree trunks are used in the construction of houses, boats and bridges that cross canals. They are used to make grids and fences. Elastic fibers that the cover the trunks are used to make camel and horse saddles. Parts of the leafstalk are used as trowels by mason and as beaters by washerwomen. Mats, plates and baskets are made with stalks. Among the other things made with palms are dye, paper, surfboards, and wax.

See Coconuts, Dates, Palm Oil, Palm Hearts, Food

Bamboo

giant bamboo Bamboo is a kind of grass that can grow to size of a tree. The stems are, hollow, polished and jointed and sometimes reach three feet across. Some flower and seed every year; other only do so one every 60 years or so. Some species of bamboo die off en masse after a single flowering. One such die off killed hundred of giant pandas in China in the 1980s. Depending on the species, the die off can occur everywhere from one every dozen year or so to once every century.

In the short term bamboo reproduce by sending up new stems rather than by producing seeds. A single root may produce as many as 100 stems. These stems breaks the soil with it nodes already formed and can grow as much as a meter in a single day. Bamboo doesn't have rings like a tree. The hollow nodes are already developed when they emerges in the spring and grows like an uncoiling party favor.

There are more than 500 species of bamboo. Some species of bamboo’such as Bambusa Arundinacea of India and Phyllostacys and China — reach heights of 100 feet. Bamboo is both flood- and drought resistant. Hikers who run out of water in the Malaysian rainforest can get about a canteen's worth by boring a hole right above the joint of large stalks of bamboo.

Bamboo is used for all kinds of things: homes, musical instruments, food, scaffolding, Bamboo has been made into a fabric used to make denim trousers. Surprisingly soft, it is naturally antimicrobial and odor resistant.

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2011