TIBET, GLACIERS AND WATER

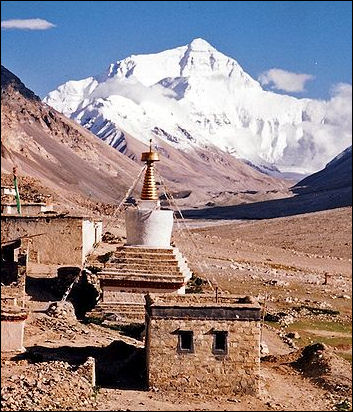

Everest from Rombok Gompa,Tibet With an average elevation of around 4,570 meters (15,000 feet), the Tibetan Plateau, is the world's highest and largest plateau, encompassing an area greater than western Europe. The vast amount of water stored in Tibetan and Himalayan glaciers play a crucial role in river flows, hydropower generation and agriculture in the Ganges, Yangtze, Mekong and Indus river systems in Asia and elsewhere.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “With nearly 37,000 glaciers on the Chinese side alone, the Tibetan Plateau and its surrounding arc of mountains contain the largest volume of ice outside the polar regions. This ice gives birth to Asia's largest and most legendary rivers, from the Yangtze and the Yellow to the Mekong and the Ganges — rivers that over the course of history have nurtured civilizations, inspired religions, and sustained ecosystems. Today they are lifelines for some of Asia's most densely settled areas, from the arid plains of Pakistan to the thirsty metropolises of northern China 3,000 miles away. All told, some two billion people in more than a dozen countries — nearly a third of the world's population — depend on rivers fed by the snow and ice of the plateau region. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“For thousands of years the glaciers have formed what Lonnie Thompson, a glaciologist at Ohio State University, calls "Asia's freshwater bank account" — an immense storehouse whose buildup of new ice and snow (deposits) has historically offset its annual runoff (withdrawals). Glacial melt plays its most vital role before and after the rainy season, when it supplies a greater portion of the flow in every river from the Yangtze (which irrigates more than half of China's rice) to the Ganges and the Indus (key to the agricultural heartlands of India and Pakistan).”

See Separate Articles: HIMALAYAS factsanddetails.com ; HIMALAYAN GLACIERS: IMPORTANCE, AVALANCHES AND DANGEROUS FLOODS factsanddetails.com; GLACIERS: THEIR MECHANICS, STRUCTURE AND VOCABULARY factsanddetails.com ; AVALANCHES factsanddetails.com; MOUNTAIN GLACIERS AND GLOBAL WARMING factsanddetails.com; STUDYING GLACIERS factsanddetails.com

Tibet and Global Warming

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “For all its seeming might and immutability, this geologic expanse is more vulnerable to climate change than almost anywhere else on Earth. The Tibetan Plateau as a whole is heating up twice as fast as the global average of 1.3̊F over the past century — and in some places even faster. These warming rates, unprecedented for at least two millennia, are merciless on the glaciers, whose rare confluence of high altitudes and low latitudes make them especially sensitive to shifts in climate.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“Natural mechanisms for sequestering atmospheric carbon dioxide are being overwhelmed by the burning of fossil fuels — coal, oil and natural gas. There is more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today than at any time during at least the past 650,000 years, based on analyses of the chemical composition of air bubbles entrapped in Antarctic ice over that time. By the end of this century, carbon dioxide levels could easily double, and many scientists expect global warming to disrupt regional weather patterns — including the Asian monsoon.”

The China Meteorological Administration calculates that temperatures on the plateau have risen an average of 0.58 degrees Fahrenheit per decade, more than four times the average warming rate in China as a whole. "A plateau is almost like a frying pan in the sky. It has to do with the way the land interacts with the atmosphere. Everywhere in the world, the mountains are heating up faster than the lowlands," said Barry Baker, a climate change expert with the Nature Conservancy, who is also studying the glaciers in Yunnan province. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, December 15, 2009]

Impact of Global Warming on Tibet

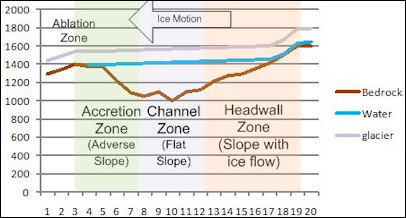

glacier overdeepening processGlobal warming is being blamed for unusual heat waves in Tibet. In 1998, Lhasa had its warmest June on record. The temperatures exceeded 77 degrees F for 23 days. People who live in the Himalayas say the sun is much stronger now than it used to be and say it snows less in the winter and the snow stays on the ground less time. By some estimates The plateau has lost 10 percent of its permafrost layer in the past decade.

The Qinghai-Tibet plateau has been warming faster than the global average with temperatures rising 0.16 degrees C per year. If the trend continues glaciers will recede significantly. The tjale — the 1.35 million square kilometer permafrost-like layer under the surface of the plateau — could thaw and be reduced by 60 percent by 2100. About 3,000 of the 4077 lakes in Qinghai Province’s Madoi County have disappeared. Large dune loom over some of the remaining ones.

There are indications that global warming could produce more precipitation in Tibet. In the past 40 years the average annual temperature in Nagqu prefecture — a 4,500-meter-high, 446,000 square kilometer on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau that accounts for 37 percent of Tibet Autonomous Region — has risen 0.6 to 1.5 degrees C. Over the same period annual precipitation has nearly doubled from 78 millimeters to 150 millimeters.

In western Tibet-Qinghai there is a mysterious "ozone valley" that thus far scientists have been unable to explain.Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The grasslands are dying out, as decades of warming temperatures — exacerbated by overgrazing — turn prairie into desert. Watering holes are drying up, and now, instead of traveling a short distance to find summer grazing for their herds, Ba O and his family must trek more than 30 miles across the high plateau. Even there the grass is meager. "It used to grow so high you could lose a sheep in it," Ba O says. "Now it doesn't reach above their hooves." The family's herd has dwindled from 500 animals to 120. The next step seems inevitable: selling their remaining livestock and moving into a government resettlement camp.[Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

Melting Glaciers in the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau

Himalayan glaciers are melting at an alarming rate. More than 15,000 glaciers in the Himalayas show evidence of shrinkage, some of it quite dramatic. Many are shrinking at a rates of 70 meters to a 100 meters a year. Some 2,000 Himalayan glaciers have disappeared since 1900. Fifteen-mile-long glaciers have lost a third of their length in the last 50 years. Many scientists think the retreat is linked to global warming. The Nepal-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development says, “small glaciers below 5,000 meters above sea level will probably disappear by the end of the century, whereas larger glaciers well above that level will still exist but be smaller.”

Glaciers in Tibet and the Himalayas are disappearing at a rate of 7 percent a year. By some estimates in the past 50 years 82 percent of the Tibetan plateau’s glacier ice has melted. Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Of the 680 glaciers Chinese scientists monitor closely on the Tibetan Plateau, 95 percent are shedding more ice than they're adding, with the heaviest losses on its southern and eastern edges. "These glaciers are not simply retreating," Thompson says. "They're losing mass from the surface down." The ice cover in this portion of the plateau has shrunk more than 6 percent since the 1970s — and the damage is still greater in Tajikistan and northern India, with 35 percent and 20 percent declines respectively over the past five decades.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“The rate of melting is not uniform, and a number of glaciers in the Karakoram Range on the western edge of the plateau are actually advancing. This anomaly may result from increases in snowfall in the higher latitude — and therefore colder — Karakorams, where snow and ice are less vulnerable to small temperature increases. The gaps in scientific knowledge are still great, and in the Tibetan Plateau they are deepened by the region's remoteness and political sensitivity — as well as by the inherent complexities of climate science.”

North Face of Everest toward Base Camp Tibet

Though scientists argue about the rate and cause of glacial retreat, most don't deny that it's happening. And they believe the worst may be yet to come. The more dark areas that are exposed by melting, the more sunlight is absorbed than reflected, causing temperatures to rise faster. (Some climatologists believe this warming feedback loop could intensify the Asian monsoon, triggering more violent storms and flooding in places such as Bangladesh and Myanmar.) If current trends hold, Chinese scientists believe that 40 percent of the plateau's glaciers could disappear by 2050. "Full-scale glacier shrinkage is inevitable," says Yao Tandong, a glaciologist at China's Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research. "And it will lead to ecological catastrophe."

David Breashears, the mountaineer and filmmaker, has been documenting the dwindling glaciers of the Himalayas and his images from Pakistan, China, and elsewhere show that some glaciers have lost up to three hundred and fifty vertical feet of ice — or, as a recent Asia Society report put it, somewhere around the height of a forty-five-story building.

Melting Himalayan Glaciers in China and Tibet

J. Madeleine Nash wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “In 2004, Chinese glaciologists published a survey of their country's 46,298 ice fields, the majority of which lie in Tibet. Compared with the 1960s, the area covered by glaciers shrank by more than 5 percent, and their volume by more than 7 percent, or more than 90 cubic miles. That much ice holds enough water to nearly fill Lake Erie. Moreover, the rate of ice loss is speeding up. Glaciers near 25,242-foot-high Naimona'nyi — the highest mountain in southwestern Tibet and the 34th highest in the world — are drawing back by eight million square feet per year, five times their rate of retraction in the 1970s”. [Source: J. Madeleine Nash, Smithsonian magazine, July 2007]

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “One of the fastest vanishing glaciers in the world is Mingyong glacier on Mt. Kawagebo, a sacred peak for Tibetan Buddhists. Out of religious sensitivity, scientists have not been permitted to work on the mountain. But through photographs they have observed that the tongue of the glacier — the farthest flung reach of snow — has retreated more than a mile and a half up the mountain.” [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, December 15, 2009]

Hiking up Kawagebo, Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “A mile and a half up the gorge that Mingyong Glacier has carved into sacred Mount Kawagebo, looming 22,113 feet high in the clouds above. There's no sign of ice, just a river roiling with silt-laden melt. For more than a century, ever since its tongue lapped at the edge of Mingyong village, the glacier has retreated like a dying serpent recoiling into its lair. Its pace has accelerated over the past decade, to more than a football field every year — a distinctly unglacial rate for an ancient ice mass. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

"This all used to be ice ten years ago," Jia Son [a farmer] says, as he scrambles across the scree and brush. He points out a yak trail etched into the slope some 200 feet above the valley bottom. "The glacier sometimes used to cover that trail, so we had to lead our animals over the ice to get to the upper meadows." Around a bend in the river, the glacier's snout finally comes into view: It's a deathly shade of black, permeated with pulverized rock and dirt. The water from this ice, once so pure it served in rituals as a symbol of Buddha himself, is now too loaded with sediment for the villagers to drink. For nearly a mile the glacier's once smooth surface is ragged and cratered like the skin of a leper. There are glimpses of blue-green ice within the fissures, but the cracks themselves signal trouble. "The beast is sick and wasting away," Jia Son says. "If our sacred glacier cannot survive, how can we?"

Melting Himalayan Glaciers on Yulong Snow Mountain

“If you want to see a glacier melt with your bare eyes, try Yulong Snow Mountain, an 18,000-foot peak in southern China's Yunnan province,” Demick wrote. “On this early December morning, the mountain is etched against the technicolor sky in shades of gray — definitely more gray than white. Naked boulders of limestone and daubs of shrubbery protrude from the shallow snow cover. In the study of climate change, glaciers are sometimes likened to the canaries in the coal mine, and to many observers the condition of Yulong ("Jade Dragon") mountain is troubling. [Demick, Op. Cit]

He Yuanqing, one of China's leading glacier experts, found that the mountain's largest glacier, known as Baishui No. 1, has retreated about 275 yards since 1982. He told the Los Angeles Times, "At this rate, the glacier could disappear entirely over the next few decades," said He, who heads a team of scientists who have been studying Yulong mountain since 1999 for the Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, a government-run think tank.

When glaciers disappear, they don't necessarily go quietly. The ice becomes unstable; gentle slopes of snow erode into steep ridges that can collapse at unpredictable times. Yulong has had two such avalanches recently — one in 2004 and another over the summer. "There are so many cracks in the ice that it could become dangerous soon for us to continue our work on the mountain," said scientist Du, who is part of the team working at Yulong.

More than 1 million tourists, most of them Chinese, visit Yulong every year. Situated just outside the quaint tourist town of Lijiang and equipped with a cable car, Yulong has some of the most accessible glaciers in China. In the park leading to the mountain, administrators have put up signs aimed at educating the public about global warming. The scientific team studying the glacier also intends to build a research station near the mountain and to open an exhibit to help tourists understand why they should worry about melting glaciers.

"Of course I'm concerned that the glaciers are disappearing," said Ye Xiaochen, 47, a factory worker from Sichuan province who was wearing new hiking gear and carrying a Japanese camera on a tour of Lijiang. "It's not true that Chinese only care about the economy — the environment is equally important." To prove his point, he turned to a colleague and snapped, "Put out that cigarette — you're making more pollution."

Shrinking Glaciers in Xinjiang

melting glacier in Xinjiang Glaciers in Xinjiang in far western China are shrinking at an alarming rate. About 80 percent of the glaciers in the Tian (Heaven) range have declined, though increased precipitation has also led a small number to expand. The 3,800-meter Urumqi No1 glacier, the first to be measured in China, has lost more than 20 percent of its volume since 1962, according to the Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute (Careeri) in Lanzhou.[Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, March 2, 2009]

“Xinjiang is particularly dependent on a steady supply of meltwater from glaciers, which act as solid reservoirs that store precipitation in the winter and release it in the summer,” Jonathan Watts, wrote in The Guardian, “Few city residents understand the problem because in recent years water supplies have surged thanks to the extra meltwater and increased rainfall. The excess supply has been used to water golf courses and make artificial snow for a ski slope in semi-desert Urumqi. But scientists say the glut is unsustainable because it comes from the release of water that has built up over thousands of years.”

“At the moment there is plenty of water in the big cities. But it is hard to say how long it will last,” He Yuanqing, a glaciologist at Careeri, told The Guardian. “On one hand, global warming is accelerating the melt. But on the other, it is increasing rainfall, so we need a way to store the extra water.”

Estimates of how long it will take Urumqi's glacial water supplies to start to decline range from 40 to 100 years. It is unclear, however, how long the water can be stored without replenishment. Experts have previously called for the reservoirs to be built underground so that the water does not evaporate in the summer, when Xinjiang has the highest average temperatures in China. Over-exploitation of river systems and oases has exacerbated the problem. The volume of water in the once vast Aibi lake in Xinjiang has decreased by two-thirds over the past 50 years, the Beijing News reported today.

Effect of Melting Himalayan Glaciers

The vast amount of water stored in Himalayan glaciers plays a crucial role in river flows, hydropower generation and agricultural run in the Ganges, Yangtze, Mekong and Indus river systems in Asia and elsewhere. J. Madeleine Nash wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The loss of high-mountain ice in the Himalayas could have terrible consequences for people living downstream. Glaciers function as natural water towers. It's the ice melt in spring and fall that sends water coursing down streams and rivers before the summer monsoon arrives and after it leaves. At present, too much ice is melting too fast, raising the risk of catastrophic flooding; the long-term concern is that soon there will be too little ice during those times when the monsoon fails, leading to drought and famine. [Source: J. Madeleine Nash, Smithsonian magazine, July 2007]

The shrinkage of Himalayan glaciers could result in water shortages that could affect more than 1 billion people, mainly people that rely on the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Mekong, Yellow, Yangtze and Salween rivers and their tributaries, which are fed by melt waters from Himalayan and Tibetan glaciers and snow.

According to a report by the WWF glacial melting is expected to increase even more. Initially the result will be flooding but this will be followed by a long steady decline of river flow that could have severe consequences on agriculture and fisheries. The melting glaciers have caused the levels of lakes to rise. The levels of 117 lakes in Nagqu prefecture have risen, The water level of Tibet’s second largest lake, Sering Ko, has rise 20 centimeters and grown to a size of 1,620 square kilometers. Since 1997, it has extended five kilometers to the west, 23 kilometers to the southwest, 3 kilometers to the south and 18 kilometers to the north. Rising water levels has submerged 106,667 hectares of pastureland and forced 1,400 household to build new homes.

One hydrologist told the Independent, "Glaciers tend to melt out in the summer and that is the time when a great deal of water is needed for agriculture. So it's precisely the time when water is most needed those glaciers give their water. And the threat is that in the future there won't be that water to use."

Effects of Melting Glaciers and Global Warming on the Tibetan Plateau

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The potential impacts extend far beyond the glaciers. On the Tibetan Plateau, especially its dry northern flank, people are already affected by a warmer climate. The grasslands and wetlands are deteriorating, and the permafrost that feeds them with spring and summer melt is retreating to higher elevations. Thousands of lakes have dried up. Desert now covers about one-sixth of the plateau, and in places sand dunes lap across the highlands like waves in a yellow sea. The herders who once thrived here are running out of options.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“Along the plateau's southern edge, by contrast, many communities are coping with too much water. In alpine villages like Mingyong, the glacial melt has swelled rivers, with welcome side effects: expanded croplands and longer growing seasons. But such benefits often hide deeper costs. In Mingyong, surging meltwater has carried away topsoil; elsewhere, excess runoff has been blamed for more frequent flooding and landslides. In the mountains from Pakistan to Bhutan, thousands of glacial lakes have formed, many potentially unstable. Among the more dangerous is Imja Tsho, at 16,400 feet on the trail to Nepal's Island Peak. Fifty years ago the lake didn't exist; today, swollen by melt, it is a mile long and 300 feet deep. If it ever burst through its loose wall of moraine, it would drown the Sherpa villages in the valley below.”

“This situation — too much water, too little water — captures, in miniature, the trajectory of the overall crisis. Even if melting glaciers provide an abundance of water in the short run, they portend a frightening endgame: the eventual depletion of Asia's greatest rivers. Nobody can predict exactly when the glacier retreat will translate into a sharp drop in runoff. Whether it happens in 10, 30, or 50 years depends on local conditions, but the collateral damage across the region could be devastating. Along with acute water and electricity shortages, experts predict a plunge in food production, widespread migration in the face of ecological changes, even conflicts between Asian powers.”

Effects of Shrinking Himalayan Glaciers on Farmers in China

Miao irrigation system Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, It's the only explanation that makes sense to Jia Son, a Tibetan farmer surveying the catastrophe unfolding above his village in China's mountainous Yunnan Province. "We've upset the natural order," the devout, 52-year-old Buddhist says. "And now the gods are punishing us." Fatalism may be a natural response to forces that seem beyond our control. But Jia Son...believes that every action counts — good or bad, large or small. Pausing on the mountain trail, he makes a guilty confession. The melting ice, he says, may be his fault.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“When Jia Son first noticed the rising temperatures — an unfamiliar trickle of sweat down his back about a decade ago — he figured it was a gift from the gods. Winter soon lost some of its brutal sting. The glacier began releasing its water earlier in the summer, and for the first time in memory villagers had the luxury of two harvests a year.”

“Then came the Chinese tourists, a flood of city dwellers willing to pay locals to take them up to see the glacier. The Han tourists don't always respect Buddhist traditions; in their gleeful hollers to provoke an icefall, they seem unaware of the calamity that has befallen the glacier. Still, they have turned a poor village into one of the region's wealthiest. "Life is much easier now," says Jia Son, whose simple farmhouse, like all in the village, has a television and government-subsidized satellite dish. "But maybe our greed has made Kawagebo angry."

Jia Son is taking no chances. Every year he embarks on a 15-day pilgrimage around Kawagebo to show his deepening Buddhist devotion. He no longer hunts animals or cuts down trees. As part of a government program, he has also given up a parcel of land to be reforested. His family still participates in the village's tourism cooperative, but Jia Son makes a point of telling visitors about the glacier's spiritual significance. "Nothing will get better," he says, "until we get rid of our materialistic thinking." It's a simple pledge, perhaps, one that hardly seems enough to save the glaciers of the Tibetan Plateau — and stave off the water crisis that seems sure to follow. But here, in the shadow of one of the world's fastest retreating glaciers, this lone farmer has begun, in his own small way, to restore the balance.

Barbara Demick wrote a similar story in the Los Angeles Times, “In the near term, the effects of the warming temperatures are a mixed blessing. In a nearby village, called Baisha, cafe tables are set out on the sidewalk to allow tourists to bask in the sunshine. Tiny plots of cabbages are kept well irrigated by the water spilling down from the mountain. For the residents, most of them members of the Naxi ethnic minority, there is much confusion about the changes in the climate. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, December 15, 2009]

"Electricity, tourists, global warming, we don't know why, but it is getting warmer and we don't have the snow that we used to," said 56-year-old He Shengxian, her feet sinking into the mud as she carried a bale of hay alongside a swollen stream. A farmer, Huang Xiaoquan, 53, says he is certain that the disappearance of the ice is "nature's punishment" against modern life. "But there's nothing we can do about it, so why worry?" said Huang.

Effect of Melting Himalayan Glaciers on India

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “It is not yet noon in Delhi, just 180 miles south of the Himalayan glaciers. But in the narrow corridors of Nehru Camp, a slum in this city of 16 million, the blast furnace of the north Indian summer has already sent temperatures soaring past 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Chaya, the 25-year-old wife of a fortune-teller, has spent seven hours joining the mad scramble for water that, even today, defines life in this heaving metropolis — and offers a taste of what the depletion of Tibet's water and ice portends.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

Chaya's day began long before sunrise, when she and her five children fanned out in the darkness, armed with plastic jugs of every size. After daybreak, the rumor of a tap with running water sent her stumbling in a panic through the slum's narrow corridors. Now, with her containers still empty and the sun blazing overhead, she has returned home for a moment's rest. Asked if she's eaten anything today, she laughs: "We haven't even had any tea yet.” Suddenly cries erupt — a water truck has been spotted. Chaya leaps up and joins the human torrent in the street. A dozen boys swarm onto a blue tanker, jamming hoses in and siphoning the water out. Below, shouting women jostle for position with their containers. In six minutes the tanker is empty. Chaya arrived too late and must move on to chase the next rumor of water.”

“Delhi's water demand already exceeds supply by more than 300 million gallons a day, a shortfall worsened by inequitable distribution and a leaky infrastructure that loses an estimated 40 percent of the water. More than two-thirds of the city's water is pulled from the Yamuna and the Ganges, rivers fed by Himalayan ice. If that ice disappears, the future will almost certainly be worse. "We are facing an unsustainable situation," says Diwan Singh, a Delhi environmental activist. "Soon — not in thirty years but in five to ten — there will be an exodus because of the lack of water."

“The tension already seethes. In the clogged alleyway around one of Nehru Camp's last functioning taps, which run for one hour a day, a man punches a woman who cut in line, leaving a purple welt on her face. "We wake up every morning fighting over water," says Kamal Bhate, a local astrologer watching the melee. This one dissolves into shouting and finger-pointing, but the brawls can be deadly. In a nearby slum a teenage boy was recently beaten to death for cutting in line.”

“For the people in Nehru Camp, geopolitical concerns are lost in the frenzied pursuit of water. In the afternoon, a tap outside the slum is suddenly turned on, and Chaya, smiling triumphantly, hauls back a full, ten-gallon jug on top of her head. The water is dirty and bitter, and there are no means to boil it. But now, at last, she can give her children their first meal of the day: a piece of bread and a few spoonfuls of lentil stew. "They should be studying, but we keep shooing them away to find water," Chaya says. "We have no choice, because who knows if we'll find enough water tomorrow."

Artificial Glaciers, Rains Rockets and Capturing Water from Melting Glaciers

Beijing is using rockets and artillery to seed clouds with rain-inducing chemicals. In Madoi County in Qinghai Province the program is so intense during the summer that the blasts of artillery keep people awake at night. Authorities insist the program is working and increasing rain and replenishing glaciers. Locals say the rockets just anger the gods and perpetuate the drought.

avalanche Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “In Ladakh, a bone-dry region in northern India and Pakistan that relies entirely on melting ice and snow, a retired civil engineer named Chewang Norphel has built "artificial glaciers"’simple stone embankments that trap and freeze glacial melt in the fall for use in the early spring growing season. Nepal is developing a remote monitoring system to gauge when glacial lakes are in danger of bursting, as well as the technology to drain them. Even in places facing destructive monsoonal flooding, such as Bangladesh, "floating schools" in the delta enable kids to continue their education — on boats.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“But nothing compares to the campaign in China, which has less water than Canada but 40 times more people. In the vast desert in the Xinjiang region, just north of the Tibetan Plateau, China aims to build 59 reservoirs to capture and save glacial runoff. Across Tibet, artillery batteries have been installed to launch rain-inducing silver iodide into the clouds. In Qinghai the government is blocking off degraded grasslands in hopes they can be nurtured back to health. In areas where grasslands have already turned to scrub desert, bales of wire fencing are rolled out over the last remnants of plant life to prevent them from blowing away.

Rockets and artillery are used to seed clouds with rain-inducing chemicals. In Madoi County in Qinghai Province the program is so intense during the summer that the blasts of artillery keep people awake at night. Authorities insist the program is working and increasing rain and replenishing glaciers. Locals say the rockets just anger the gods and perpetuate the drought.

Due to concerns over the future water supply posed by global warming, China plans to create 59 reservoirs to collect meltwater from shrinking glaciers in Xinjiang province, home of some of the world’s highest peaks and widest ice fields. The 10-year engineering project, which aims to catch and store glacier run-off that might otherwise trickle away into the desert. [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, March 2, 2009] Behind the measure is a desire to adjust seasonal water levels and address longer-term concerns that downstream city residents will run out of drinking supplies once the glaciers in the Tian, Kunlun and Altai mountains disappear.

In the first phase, 29 reservoirs will be built with a combined capacity of 21.8 billion cubic meters of water, according to the Xinhua news agency. Funding of about $30 million a year for three years, staring in 2010, has been approved for the project. Wang Shijiang, director of Xinjiang Water Resource Department, told Xinhua that the mountain reservoir system was designed to “intercept” meltwater so that it could be used more efficiently for irrigation and to adjust for seasonal variations in rainfall.

Water Shortages and the Politics of Melting Himalayan Glaciers

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “As the rivers dwindle, the conflicts could spread. India, China, and Pakistan all face pressure to boost food production to keep up with their huge and growing populations. But climate change and diminishing water supplies could reduce cereal yields in South Asia by 5 percent within three decades. "We're going to see rising tensions over shared water resources, including political disputes between farmers, between farmers and cities, and between human and ecological demands for water," says Peter Gleick, a water expert and president of the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California. "And I believe more of these tensions will lead to violence." [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“The real challenge will be to prevent water conflicts from spilling across borders. There is already a growing sense of alarm in Central Asia over the prospect that poor but glacier-heavy nations (Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan) may one day restrict the flow of water to their parched but oil-rich neighbors (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan). In the future, peace between Pakistan and India may hinge as much on water as on nuclear weapons, for the two countries must share the glacier-dependent Indus.”

“The biggest question mark hangs over China, which controls the sources of the region's major rivers. Its damming of the Mekong has sparked anger downstream in Indochina. If Beijing follows through on tentative plans to divert the Brahmaputra, it could provoke its rival, India, in the very region where the two countries fought a war in 1962.”

Members of the Nepalese Cabinet fear climate change poses a threat to glaciers and want developed nations to pledge 1.5 per cent of their earnings to protect the environment.

Melting Snow in Himalayas Helps Produce Huge Algae Blooms Visible from Space

Annapurna, world's highest 10th mountainMelting snow in the Himalayas has led to enormous growth of a ‘green slime’ in the Arabian Sea, with swirls of it visible from space. Rob Waugh wrote in Yahoo News UK: “Research published in Nature’s Scientific Reports used NASA satellite imagery to track the growth of the planktonic organism Noctiluca scintillans in the Arabian sea. “It was unheard of 20 years ago, but the huge blooms have grown to such an extent that it has disrupted the food chain and could threaten fisheries which sustain 150 million people. “The millimeter-size planktonic organism has forced out the photosynthesising plankton that used to support life in the area [Source: Rob Waugh, Yahoo News UK, May 6, 2020].

Joaquim Goes, from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said: “This is probably one of the most dramatic changes that we have seen that’s related to climate change.” “We are seeing Noctiluca in Southeast Asia, off the coasts of Thailand and Vietnam, and as far south as the Seychelles, and everywhere it blooms it is becoming a problem. It also harms water quality and causes a lot of fish mortality.”

“Normally, cold winter monsoon winds blowing from the Himalayas cool the surface of the oceans.But with the shrinking of glaciers and snow cover in the Himalayas, the monsoon winds blowing offshore from land are warmer and more moist, meaning that Noctiluca blooms have flourished. Noctiluca (also known as sea sparkle) doesn’t rely only on sunlight and nutrients; it can also survive by eating other microorganisms. This dual mode of energy acquisition gives it a tremendous advantage to flourish and disrupt the classic food chain of the Arabian Sea.

“Noctiluca blooms first appeared in the late 1990s. In Oman, desalination plants, oil refineries and natural gas plants are now forced to scale down operations because they are choked by Noctiluca blooms and the jellyfish that swarm to feed on them. The resulting pressure on the marine food supply and economic security may also have fuelled the rise in piracy in countries like Yemen and Somalia.

“The study provides compelling new evidence of the cascading impacts of global warming on the Indian monsoons, with socio-economic implications for large populations of the Indian sub-continent and the Middle East. “Most studies related to climate change and ocean biology are focused on the polar and temperate waters, and changes in the tropics are going largely unnoticed,” said Goes.

Affect of Shrinking Glaciers in the Himalayas Not as Bad as Previously Thought

Michael Casey of AP wrote, “Nearly 60 million people living around the Himalayas will suffer food shortages in the coming decades as glaciers shrink and the water sources for crops dry up” according to a study by Dutch scientists writing in the journal Science. The scientists concluded the impact would be much less than previously estimated a few years ago by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The U.N. report in 2007 warned that hundred of millions of people were at risk from disappearing glaciers. [Source: Michael Casey, AP Environmental Writer, June 10, 2010]

The reason for the discrepancy, scientists said, is that some basins surrounding the Himalayas depend more on rainfall than melting glaciers for their water sources. Those that do count heavily on glaciers like the Indus, Ganges and Brahamaputra basins in South Asia could see their water supplies decline by as much as 19.6 percent by 2050. China's Yellow River basin, in contrast, would see a 9.5 percent increase precipitation as monsoon patterns change due to the changing climate.

"We show that it's only a certain areas that will be effected," said Utrecht University Hydrology Prof. Marc Bierkens, who along with Walter Immerzee and Ludovicus van Beek conducted the study. "The amount of people effected is still large. Every person is one too many but its much less than was first anticipated."

The study is one of the first to examine the impact of shrinking glaciers on the Himalayan river basins. It will likely further fuel the debate on the degree that climate change will devastate the river basins that are mostly located in India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and China. The findings by the Dutch team in Science were greeted with caution with glacial experts who did not take part in the research. They said the uncertainties and lack of data for the region makes it difficult to say what will happen to the water supply in the next few decades. Others like Zhongqin Li, director of the Tianshan Glaciological Station in China, said the study omitted several other key basins in central Asia and northwest China, which will be hit hard by the loss of water from melting glaciers.

Still, several of these outside researchers said the findings should reaffirm concerns that the region will suffer food shortages due to climate change, exasperating already existing concerns such as overpopulation, poverty, pollution and weakening monsoon rains in parts of South Asia. "The paper teaches us there's lot of uncertainty in the future water supply of Asia and within the realm of plausibility are scenarios that may give us concern," said Casey Brown, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Massachusetts. "At present, we know that water concerns are already a certainty — the large and growing populations and high dependence on irrigated agriculture, which makes the region vulnerable to present climate variability," he said.

Bierkens and his fellow researchers said governments in the region should adapt to the projected water shortages by shifting to crops that use less water, engaging in better irrigation practices and building more and larger facilities to store water for extended periods of time. "We estimate that the food security of 4.5 percent of the total population will be threatened as a result of reduce water availability," the researchers wrote. "The strong need for prioritizing adaptation options and further increasing water productivity is therefore eminent."

Tibet's Permafrost Seems to Reduce CO2

Pakistan's Gasherbrum I, world's highest 11th mountainIn the Tibetan Plateau, climate change is increasing the carbon concentrations in the upper layers of permafrost soils, a study has shown. This represents a negative feedback to rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations, and could potentially slow the pace of climate change.

According to the International Business Times: Permafrost soils are known to store large amounts of carbon. As temperature rise and permafrost thaws, some of this carbon is released into the atmosphere. However, the upper layers of the permafrost soils can also trap a certain amount of carbon. [Source: Léa Surugue, International Business Times, May 8, 2017]

"In these cold regions as it gets warmer, the vegetation grows more and that puts more carbon in the top layers of the soil. What we are concerned about is the carbon that is in the frozen permafrost, deeper in the soil. Whether or not you have a bigger emission of carbon depends on the balance between how much carbon is released from those deep soils when permafrost thaws versus how much enters at the top", permafrost expert Sarah Chadburn from the University of Exeter (who was not involved with the study) told IBTimes UK. "Our models tend to predict that more carbon is coming out but it is helpful to get precise measurements of carbon concentrations at the top of the soil to get a better idea of how the whole system affects global warming".

So far, the effects of warming on the balance of carbon uptake and loss in permafrost regions has remained unclear. More accurate measurements of carbon concentration in permafrost soils are needed. The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, is based on repeated soil carbon measurements at more than 100 sites in the Tibetan Plateau, taken in the early 2000s and early 2010s. "This study is particularly interesting because it's coming from an area that was underrepresented in the scientific literature in terms of studying the carbon balance associated with thawing permafrost", Vladimir Romanovsky, from the Permafrost Laboratory at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (who was not involved with the research) told IBTimes UK.

The study's authors report an accumulation of soil organic carbon in the uppermost 30cm of the permafrost soils over this decade – a period when temperatures kept rising in the Tibetan Plateau. The scientists hypothesise that this increase in carbon stocks is probably the result of climate change-related vegetation growth in the region. Their findings suggest that the upper layer of the permafrost represents a substantial regional carbon sink to rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations in a warning climate. As such, it could help offset carbon losses from the deeper thawing permafrost and slow the pace of climate change.

Its not clear whether the findings also apply to other regions. Chadburn commented: "The Tibetan Plateau is a bit different to other permafrost regions. Most regions are at higher latitudes, like the Arctic permafrost region, whereas the Tibet Plateau is Alpine mountain permafrost. It's much further south so it is a different kind of climate. We don't know if these findings could apply to other permafrost regions. But we need to do the same kind of studies in other areas because such measurements are really useful to understand the role of permafrost in furthering climate change".

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2022