NANCHAO PERIOD (A.D. 650–1250)

Located on the southwestern border of China’s Tang empire (A.D. 618–907), Nanchao served as a buffer for and later rival to China. The Tai originally lived in Nanchao. The state of Nanchao played a key role in Tai development. In the mid-seventh century A.D., the Chinese Tang Dynasty, threatened by powerful western neighbors like Tibet, sought to secure its southwestern borders by fostering the growth of a friendly state formed by the people they called man (southern barbarians) in the Yunnan region. This state was known as Nanchao. Originally an ally, Nanchao became a powerful foe of the Chinese in subsequent centuries and extended its domain into what is now Burma and northern Vietnam. In 1253 the armies of Kublai Khan conquered Nanchao and incorporated it into the Yuan (Mongol) Chinese empire. [Source: Library of Congress]

Nanchao's significance for the Tai people was twofold. First, it blocked Chinese influence from the north for many centuries. Had Nanchao not existed, the Tai, like most of the originally non-Chinese peoples south of the Chang Jiang, might have been completely assimilated into the Chinese cultural sphere. Second, Nanchao stimulated Tai migration and expansion. Over several centuries, bands of Tai from Yunnan moved steadily into Southeast Asia, and by the thirteenth century they had reached as far west as Assam (in present-day India). Once settled, they became identified in Burma as the Shan and in the upper Mekong region as the Lao. In Tonkin and Annam, the northern and central portions of present-day Vietnam, the Tai formed distinct tribal groupings: Tai Dam (Black Tai), Tai Deng (Red Tai), Tai Khao (White Tai), and Nung. However, most of the Tai settled on the northern and western fringes of the Khmer Empire.

First Thai Kingdom in Sukhothai

The Thais didn't really enter the scheme of things in Southeast Asia until the 13th century, when large numbers of Thais fled present-day Burma and China to escape the Mongol armies of Kublai Khan. The Thais set up a kingdom in Khmer territory at Sukhothai.

The Thai have traditionally regarded the founding of the kingdom of Sukhothai as marking their emergence as a distinct nation. Tradition sets 1238 as the date when Tai chieftains overthrew the Khmer at Sukhothai, capital of Angkor's outlying northwestern province, and established a Tai kingdom. A flood of migration resulting from Kublai Khan's conquest of Nanchao furthered the consolidation of independent Tai states. Tai warriors, fleeing the Mongol invaders, reinforced Sukhothai against the Khmer, ensuring its supremacy in the central plain. In the north, other Tai war parties conquered the old Mon state of Haripunjaya and in 1296 was involved in the founding of the kingdom of Lan Na with its capital at Chiang Mai.

The Kingdom of Sukhothai, meaning the Dawn of Happiness, is regarded as the beginning of the Thai nation state and the cradle of Thai civilization. Situated on the banks of the Mae Nam Yom some 375 kilometers north of present-day Bangkok, it is the place where Thailand’s institutions, writing system and culture first developed. Indeed, it was there in the late thirteenth century that the people of the central plain, lately freed from Khmer rule, took the name Thai, meaning "free," to set themselves apart from other Tai speakers still under foreign rule.

Sukhothai Period (1238–1438)

In 1238 a Tai chieftain, Sri Intraditya, declared independence from Khmer overlords and established a kingdom at Sukhothai in the Chao Phraya Valley in central Thailand. The people of the central plain took the name “Thai” , which means “free,” to distinguish themselves from other Tai people still under foreign rule. According to Lonely Planet it “quickly expanded its sphere of influence, taking advantage not only of the declining Khmer power but the weakening Srivijaya domain in the south. Under King Ramkhamhaeng, the Sukhothai kingdom extended from Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south to the upper Mekong River valley (Laos) and to Bago (Myanmar). For a short time (1448–86) the Sukhothai capital was moved to Phitsanulok. It was annexed by Ayuthaya in 1376, by which time a national identity of sorts had been forged.

The Kingdom of Sukhothai conquered the Isthmus of Kra in the thirteenth century and financed itself with war booty and tribute from vassal states in Burma, Laos, and the Malay Peninsula. During the reign of Ramkhamhaeng (Rama the Great, r. 1279–98), Sukhothai established diplomatic relations with the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) in China and acknowledged China’s emperor as its nominal overlord. After Ramkhamhaeng’s death, the vassal states gradually broke away; a politically weakened Sukhothai was forced to submit in 1378 to the rising new Thai Kingdom of Ayutthaya and was completely absorbed by 1438. [Source: Library of Congress]

Endowed with rich natural resources at their disposal, the people were engaged primarily in agriculture. After the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng, however, the Sukhothai Kingdom lost much of its power. After the death of King Maha Thammaracha I, or King Lithai, in 1370 Sukhothai further declined in power, and various satellite states gradually broke away. The establishment of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya to the south in 1350 also affected Sukhothai’s stability, as Ayutthaya was situated in a more strategic and more fertile location than Sukhothai was. Owing to the combination of all these factors, compounded by internal political problems, the Kingdom of Sukhothai was finally merged into the Ayutthaya Kingdom, with merely the status of a local center north of Ayutthaya. [Source:Thailand Foreign Office, The Government Public Relations Department]

During and following the Sukhothai period, the Thai-speaking Kingdom of Lan Na flourished in the north near the border with Burma. With its capital at Chiang Mai, the name also sometimes given to this kingdom, Lan Na emerged as an independent city-state in 1296. Later, from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, Lan Na came under the control of Burma. See Lanna Below.

See Separate Article SUKHOTHAI AND THE RUINED TEMPLES AND NATIONAL PARKS NEAR IT factsanddetails.com

King Ramkhamhaeng and Other Sukhothai Period Rulers

Sukhothai was established in 1238 by King Si Inthrathit, who established the tradition of a benign, fatherly rule. The best-known ruler of the Kingdom of Sukhothai, however, was King Ramkhamhaeng, his second son, who guided the Sukhothai Kingdom to the zenith of progress and prosperity in terms of the economy, the arts, culture, and power. As a 19 year old prince of a fledgling kingdom, Rama led his fathers troops to victory and thus earned the name Ramkhamhaeng (Rama the Bold).

Ramkhamhaeng (Rama the Great, 1277-1298) is the first ruler of Sukhothai for whom historical records survive. He was a famous warrior who claimed to be "sovereign lord of all the Tai" and financed his court with war booty and tribute from vassal states in Burma, Laos, and the Malay Peninsula. Ramkhamhaeng invented the Thai script and had a stone inscription made. In his reign, the Kingdom of Sukhothai expanded in territory and especially in economic clout, as the Kingdom embraced a free trade system, levying no taxes. Sukhothai thus grew into a major trade hub and a center of diverse cultures. [Source: Thailand Foreign Office, The Government Public Relations Department]

As king Ramkhamhaeng was a populist, assuring his subjects of fair treatment and allowing them freedom to worship animist spirits while staunchly supporting the development of Buddhism. The kingdom of Sukhothai flourished during his reign as he generally chose to avoid unnecessary conflict and allied himself with King Mangrai of Lan Na and Ngam Muang of Phayao. Almost exclusively under the reign of King Ramkhamhaeng was Sukhothai an expansive and prosperous kingdom that would develop an artistic style renowned for its great beauty.

During Ramkhamhaeng’s reign, the Thai established diplomatic relations with China and acknowledged the Chinese emperor as nominal overlord of the Thai kingdom. Ramkhamhaeng brought Chinese artisans to Sukhothai to develop the ceramics industry that was a mainstay of the Thai economy for 500 years. He also devised the Thai alphabet by adapting a Khmer script derived from the Indian Devanagari script.

King Maha Thammaracha I, or King Lithai, who ruled Sukhothai during the period 1347-1370, brought in Buddhism, to be propagated among the citizens and to restore the administration. Sukhothai declined rapidly after Ramkhamhaeng's death, as vassal states broke away from the suzerainty of his weak successors. Despite the reputation of its later kings for wisdom and piety, the politically weakened Sukhothai was forced to submit in 1378 to the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya.

Ramkhamhaeng Stele

King Ramkhamhaeng the Great’s reign is noted as a time of prosperity and well-being, as recorded in a stone inscription well-known to Thais. Part of the so-called Ramkhamhaeng inscription reads: “This realm of Sukhothai is good. In the water there are fish; in the fields there is rice. The ruler does not levy a tax on the people who travel along the road together, leading their oxen on the way to trade and riding their horses on the way to sell. Whoever wants to trade in elephants, so trades. Whoever wants to trade in horses, so trades. Whoever wants to trade in silver and gold, so trades.”

The inscription records that King Ramkhamhaeng set up a bell at one of the gates to allow his subjects to seek the help to the king to settle dispute, seek justice and voice their grievances. The passage related to this reads: “The king has hung a bell in the opening of the gate over there; if any commoner has a grievance which sickens his belly and grips his heart, he goes and strikes the bell. King Ram Khamhaeng questions the man, examines the case and decides it justly for him.”

Mant think the Ramkhamhaeng stele is a 19th century fabrication. According to to Wikipedia: “This stone was allegedly discovered in 1833 by King Mongkut (then still a monk) in Wat Mahathat. The authenticity of the stone – or at least portions of it – has been brought into question. Piriya Krairiksh, an academic at the Thai Khadi Research institute, notes that the stele's treatment of vowels suggests that its creators had been influenced by European alphabet systems; he concludes that the stele was fabricated by someone during the reign of Rama IV or shortly before. The subject is very controversial, since if the stone is a fabrication, the entire history of the period will have to be re-written.

Scholars are divided over the issue about the stele's authenticity. It remains an anomaly amongst contemporary writings, and in fact no other source refers to King Ramkhamhaeng by name. Some authors claim the inscription was completely a 19th-century fabrication, some claim that the first 17 lines are genuine, some that the inscription was fabricated by King Lithai (a later Sukhothai king). Most Thai scholars still hold to the inscription's authenticity. The inscription and its image of a Sukhothai utopia remain central to Thai nationalism, and the suggestion it may have been faked caused Michael Wright, an expatriate British scholar, to be threatened with deportation under Thailand's lèse majesté laws.

The Ram Khamhaeng stele has also been brought into the discussions of the Wat Traimit Golden Buddha, a famous Bangkok tourist attraction. In lines 23-27 of the first stone slab of the stele, "a gold Buddha image" is mentioned as being located "in the middle of Sukhothai City". This has been interpreted by some scholars as referring to the Wat Traimit Golden Buddha.

Ruins of Sukhothai Today

Sukhothai (375 kilometers north of Bangkok) was the capital of Thailand's first important kingdom and the birthplace of the Thai alphabet and many elements of Thai culture. Founded in 1238, it existed for only 100 years before it was superseded by Ayutthaya in the late 14th century. Today, Sukhothai is a large historical park with one of Thailand's most impressive set of ruins. Restored by the Fine Arts Department and named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1991, it features the remains of a royal palace, several major Buddhist temples, ruined walls and a complex system of canals and ponds used to supply water to the city. Sukhothai architecture is dominated by Lotus-bud-shaped stupas.

The temples and ruins at Sukhotahi receive less tourists than the ones at Ayutthaya. Because they are spread out over a large area, many tourist get around in carts pulled by white oxen. A good place to start a visit to Sukotahi is the Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, which has a large collection of Buddha images, ceramics and art objects discovered at Sukhothai and nearby provinces as well as a model of the old city, which will give you a sense of what the ancient city is like as whole. The walking Buddha of Sukhothai at the museum is one of Thailand's most famous works of art.

Across a foot bridge from the museum is Wat Trapang, which is still in use. The largest and most significant group of ruins, at Wat Mahathat, contains the remains of 198 chedis, numerous stone Buddhas, columns, and lotus-bud towers, many of which are still standing. A pond in front of this Wat provides a nice reflection of the site. The open three-sided Wat Sri Chum contains a massive sitting Buddha that measures 35 feet from knee to knee. Here, children with candles will show you how to get to a secret tunnel. Wat Sra Sri, situated on an island in the middle of a pond, features several elaborately inscribed stone prangs. To the east is Wat Chang Lom, with a chedi surrounded by 36 stone elephants. A mile to the west standing on a hillside is a large Buddha which looks down on the city.Also worth checking out are the four major stone gates to Sukhotahi, with inscriptions written in Thai, Chinese and Burmese; Wat Sau, with a famous seated Buddha; Si Sawai, with three Lopburi-style stupas; Si Awai, containing a Hindu shrine; and the Noi Thurin Kilns, a group of 500 kilns scattered over a square mile area.

Si Satchanalai (45 kilometers north of Sukhothai) was a satellite city during the Sukhothai period. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and located on the banks of the Yom River, this group of ancient temples is regarded as more impressive and beautifully situated than those at Sukhothai. Among the most interesting ruins are Wat Chedi Jet Thae, featuring a group of intricately-carved stupas; Wat Chang Lom, with chedi surrounded by Buddha statues and 39 elephant buttresses; and Wat Phra Si Ratana Mahathat, which has a well-preserved prang surrounded by seated and standing Buddhas. Nearby Golden Mountain provides a good view of the ancient city and river which flows through it.

Kamphaeng Phet (in the Sukhothai area) has also been designated as a UNESCO World heritage Site. An important center of the Sukhothai kingdom, this walled city contains a number of interesting structures from the 13th and 14th century. They include Wat Phra That, with a beautiful round chedi; Wat Phra Kaeo, with a huge seated Buddha; and Lak Muang, the foundation stone of the city. There are also forest temples to the north of the city.

Early Thai Kings

Thai rulers were absolute monarchs whose office was partly religious in nature. They derived their authority from the ideal qualities they were believed to possess. The king was the moral model, who personified the virtue of his people, and his country lived at peace and prospered because of his meritorious actions. At Sukhothai, where Ramkhamhaeng was said to hear the petition of any subject who rang the bell at the palace gate to summon him, the king was revered as a father by his people. But the paternal aspects of kingship disappeared at Ayutthaya, where, under Khmer influence, the monarchy withdrew behind a wall of taboos and rituals. The king was considered chakkraphat, the Sanskrit-Pali term for the "wheel-rolling" universal prince who through his adherence to the law made all the world revolve around him. As the Hindu god Shiva was "lord of the universe," the Thai king also became by analogy "lord of the land," distinguished in his appearance and bearing from his subjects. According to the elaborate court etiquette, even a special language, Phasa Ratchasap, was used to communicate with or about royalty.

As devaraja (Sanskrit for "divine king"), the king ultimately came to be recognized as the earthly incarnation of Shiva and became the object of a politico-religious cult officiated over by a corps of royal Brahmans who were part of the Buddhist court retinue. In the Buddhist context, the devaraja was a bodhisattva (an enlightened being who, out of compassion, foregoes nirvana in order to aid others). The belief in divine kingship prevailed into the eighteenth century, although by that time its religious implications had limited impact.

The early Thai kings could be quite cruel. On occasion they had pregnant women captured and crushed by elephants so that their fierce spirits would protect the Thai capital from attack.

King Trailok and the Saktina System

One of the numerous institutional innovations of King Trailok (1448-88) was to create the position of uparaja, or heir apparent, usually held by the king's senior son or full brother, in an attempt to regularize the succession to the throne — a particularly difficult feat for a polygamous dynasty. In practice, there was inherent conflict between king and uparaja and frequent disputed successions.

By fusing Hindu and Confucian ideas with Thai interpretations, King Trailok also developed the “saktina” system of political, social and hierarchal organization that lasted until the 20th century and still exerts an influence today. King Trailok realized that land ownership was the key behind wealth and power and set up the system in which no person posed a threat to the monarchy and the only way they could increase their land holdings or wealth was through royal patronage.

Under the saktina system each landowner was given a number which corresponded to the amount of land he owned. This number was called “ saktina”, literally “power of the fields.” Top officials, the “Chao Phya”, held a grading of 10,000 and were allowed to own up to 4,000 acres of land. Peasants on the other hand had a grading of only 20 and were not allowed to own more than 10 acres (eight is regarded as enough to support of family of six).

A man’s first wife held half the saktina points as her husband. A minor wife held one quarter. Slave’s held nothing but if a female slave of the landowner gave birth to child she attained the same status of a minor wife. People were taxed, punished and compensated in relation to their saktina. Economic and social life were bound to the system. For example, if a group of people met with a slightly smaller group of people, the smaller group would wai to the larger group. The saktina didn’t adapt very well to modern commerce and international trade and was abolished, along with slavery in 1905 under King Chulalongkorn.

Lan Na Kingdom

Lanna, Lan Na or Lannathai, was a prosperous self-ruling kingdom, once the power base of the whole of Northern Thailand as well as parts of present-day Myanmar and Laos. Its name means "Land of a Million Rice Fields.” Lanna extended across northern Thailand to include Wiang Chan (present-day Vientiane in Laos) along the middle part of the Mekong River. In the 14th century Wiang Chan was taken from Lanna by Chao Fa Ngum of Luang Prabang, who made it part of his Laotian Lan Xang (Million Elephants) kingdom. Wiang Chan prospered as an independent kingdom for a short time during the mid-16th century and eventually became the capital of Laos. After a period of dynastic decline, Lanna fell to the Burmese in 1558. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Thai historians have long painted Lanna as a kingdom that was destined to be part of Thailand, but in reality it had little to do with Siam before the late 19th century other than fighting a few battles in the 15th century and conducting a couple of expeditions in the 17th and 18th centuries. Historian Chris Baker said they “had about the same level of contact, as between, say, France and Sweden. Very little in the way of language, culture administrative practices or whatever seems to have been exchanged.”

The rich culture and history of Lan Na (and northern Thailand today) owe much to the influence of Burma and, to a certain extent Laos. Still found in northern temples is the script of Lanna, which is probably the original Thai script and thought to be based on Mon. A similar script is still in use today by the Shan people. Today Lan Na is completely different from other provinces of Thailand in cuisine, culture and custom.

Chris Baker wrote in the Bangkok Post: “the topography of narrow valleys separated by north-south hill ranges shaped the social geography” of Lan Na. “For safety people coagulated in “mueang” centres and surrounding clusters of villages. Each mueang was relatively independent, and the population sparse. Lan Na emerged under Phraya Mengrai and his successors, from the late 13th century onwards. But it did not suddenly pop up in 1296 with the founding of Chiang Mai, Mengrai had been greatly elevated by later historiography, because that is what happens to founders. But his main contribution was to establish some warrior domination over the nueang in the Kok, Ping and Wang rivers. Lan Na became something than just a loose and limited confederation over the following century...The term “Lan Na” was first used under Mengrai’s successor, Kuena, in the mid-14th century, and only in general use in the mid 15th century. [Source: Chris Baker, Bangkok Post, March 2006]

“The factor which transformed warrior politics into something more like statehood seems to have been Buddhism. The process began when Mengrai seized the established Mon Buddhist center of Hariphunchai (Lampun) in 1287 for reasons which had nothing to do with religion: ‘We have heard the news that Haribhunjaya is very rich—richer than our own domain. How can we make it our own? The process gathered more momentum after proselytizing monks brought the Lankan version of Buddhism north from Sukhothai over the next century . Along with the teaching came writing, literacy, learning and art. The city’s monks wrote scriptures and chronicles, and the city’s foundries turned out huge beautiful Buddhist images. Chiang Mai became a center of culture which elevated the city above other mueang, its ruler gaining prestige and legitimacy as the protector of this resplendent place.”

But politics lagged behind culture. The political structure remained fairly simple. Succession was by openly contest within the ruling clan. The four key government posts were occupied by members of the ruling family . A truculent council of nobles provided some checks and balances. Taxation was mostly by a levy on people’s labour. Outlying mueang were integrated by the personal fealty of ruler to ruler which broke down at every succession.

Book: “History of Lan Na” by Sarassawadee Ongsakul (Silkworm Books, 2005]

See Separate Article LANNA KINGDOM factsanddetails.com

Mongols in South-East Asia

Present-day Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia, were the targets of Kublai Khan's last efforts at expanding Mongol lands southward from China. The jungle-covered, hot and humid lands of Southeast Asia were quite different from the steppes of Central Asia and stretched the Mongol armies to their limits. There were also the challenges of a sea transport and unfamiliar styles of warfare.

According to historian Stephen Turnbull: “The Mongols had fought everywhere from the steppes of Mongolia to the snowy forests of Russia, from the mountains in Korea to the deserts of Syria but it was in the jungles of south-east Asia were the Mongols were faced with conditions and factors that were the most unfamiliar to them. These factors, most notably the heat and humidity took their toll on the Mongol military. Dense jungles, tropical swamps and long rivers were not suited to Mongol styles of warfare and although the Mongol army was able to adapt they were essentially never in their element during any of their south-east Asian campaigns.” [Source: “The Mongols” by Stephen Turnbull; “Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests” by Stephen Turnbull; Bloodswan: medieval2.heavengames.com ^]

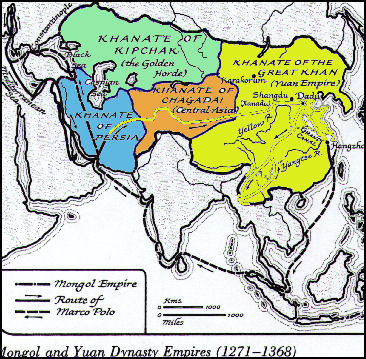

The Mongol wars in Southeast Asia marked the southern limit of the Mongol conquests. By this time the Mongol empire had split into various khanates with the most notable being the Il-khans of Persia, the Golden horde of Russia and the Jagadai khanate of central Asia. On top of this was the Yuan dynasty of China founded by Kublai Khan. A series of wars between the khanates effectively ended Mongol expansion westward whilst the campaigns against Japan and in Southeast Asia ordered under Kublai ended eastward expansion of the Yuan Mongol-Chinese Empire. These campaigns were very costly and many ended without effectively achieving their goals. The Mongol failures in Southeast Asia and Japan also marked the beginning of the end of Mongol power in China by undermining the Yuan dynasty's formidable military reputation.

Mongols and Siam and Khmer Empire

Historian Stephen Turnbull wrote: The Mongol campaigns in Siam were vastly different from those of the others already mentioned. The land we know as Thailand today was at this time a number of separate states. King Ramkhamhaeng of Siam whose capital was at Sukhothai took a very different approach to the Mongol empire than his contemporaries in Burma and Java. The king of Siam actively sought good relations with Kublai and negotiated a treaty of amity with the Yuan dynasty in 1282. He made a personal visit to China to see the khan shortly before his death in 1294. [Source: “The Mongols” by Stephen Turnbull; “Genghis Khan and the Mongol Conquests” by Stephen Turnbull, Bloodswan: medieval2.heavengames.com ^]

To the north of Siam was the kingdom of Lan Na. It was ruled by King Mangrai whose capital was at Chiang Mai. A border dispute led to war in 1296 but an expedition carried out in 1301 ended in a Mongol disaster.^

The only other kingdom not yet mentioned is that of the Khmers of Cambodia. This once glorious empire that built the wonderful temples, shrines and palaces of Angkor was already overrun by Thais. They had already taken Sukhothai from the Khmers in 1220 and made it their capital. Ramkhamhaeng played a master-stroke in this regard. Whilst the Mongols threatened to destroy their enemies in Burma and Vietnam and with his Northern opponent in Lan Na in a state of concern, King Ramkhamhaeng could prosper at the Khmer's expense. His Mongol allies had no concern over his realm and if matters changed, he still had Lan Na as a buffer in the north. Angkor held out until 1431 when it was finally taken by the Siamese. ^

Thai-Chinese Caravans

Dating back at least to the 15th century a caravan existed between southern China and northern Thailand. Controlled during much of its duration by Muslim traders, it followed three main routes through present-day Myanmar and Laos and utilized mules and ponies as beasts of burden in China and water buffalo, oxen and elephants in Southeast Asia. The British chronicler Ralph Fitch, who traveled in Southeast Asia from 1583 to 1591 wrote: “To the town of Jamahey [Chiang Mai] comes many merchants out of China, and bring a great store of Muske, Gold, Silver, and many other things of Chinese worke.”

Goods that moved south from China to Southeast Asia included silk, opium, tea, dried fruit, ponies, musk lacquerware and mules. Goods that moved north from Southeast Asia to China included gold, copper, cotton, edible bird’s nests, betel nut, tobacco, betel nut and ivory. The famous night market in Chiang Mai has its roots in this trade. Luang Prabang in Laos was a major caravan stop.

These Yunnanese Muslim traders were called “Ho” or “Chin Ho” in Thai.Wang Luilan of Kyoto University wrote: “In the nineteenth century, Ho caravans coming to Thailand from Yunnan increased in number, and their details were recorded by Western travelers and missionaries who were also moving around the region. Ho caravans traveled to and from Yunnan, Burma, Laos, and northern Thailand, with only a few traders settling along the way. They journeyed south to Thailand once or twice a year, normally in the dry season, bringing hand-woven cottons, felts, silks, medicines, and daily goods from Yunnan and returning home with ivory and traditional medicines, such as pilose antlers (Antrodia), tiger and leopard skins and bones, and bear livers. From Burma they brought opium poppies, a valuable trading commodity. [Source: Wang Luilan, Kyoto University, March 2004]

Yunnanese Muslims began settling in what is now northern Thailand in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Wang wrote: “Although most of them went back to China as merchants, some of them started to settle in the area. As their numbers gradually increased, families gathered to form communities. Currently, the greatest number of Yunnanese mosques are in the districts of Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong Son, with some in Lampang. As of 1997, the mosques had become the centers of Yunnanese Muslim communities of approximately 250 households (1,500 people). The Baan Ho mosque, the oldest in Chiang Mai City, is today the heart of the Yunnanese Muslim community. It was established in the early twentieth century by a trader called Zheng who hailed from Yuxi in Yunnan province. Zheng left Yunnan and passed through Kengtung in Burma, Lampang, Tak (where he married a local Thai woman), Lamphun, and Mae Sai, along the Thai-Burmese border. In 1905, he migrated to Chiang Mai City.

Decline and End of Lan Na

Lanna's power began to wane by the end of the 15th century and was repeatedly attacked by Lao and Burma whose troops and puppet lords occupied the area on many occasions. They introduced their own styles of food, buildings, costume and culture. Chiang Mai swayed between Burmese and Central Thai control with intermittent spells of self-government; The Burmese occupied the Lan Na region from 1556 until it was finally annexed by Central Thailand in the late 18th century. However their loyalties of the locals were to themselves and they sided with Thai or Burmese armies at different periods. [Source: Tourist Authority of Thailand]

Chris Baker wrote in the Bangkok Post: “The Burmese took the whole lot over in 1556 in just three days...The Burmese started well by imposing only a light, indirect rule. They respected local custom, kept the local rulers and nobles in place, and left well enough alone. But indirect rule rarely works well, and from 1664 the Burmese switched to direct control by military garrisons. This regime became more and more extractive and oppressive until the area was seething with petty revolts led by monks, holy men, displaced nobles and bandits....Then Lan Na almost disappeared, the late 18th century was a devastating period throughout the region. Warriors had the new idea that war was not just about winning precedence but about wiping rival capitals off the map. Chiang Mai was totally abandoned...and did not fully recover for over 50. Large areas of Lan Na were totally depopulated and not occupied for over a century. [Source: Chris Baker, Bangkok Post, March 2006]

Chiang Mai was deserted for 15 years (1776-1791) as the result of successive wars. Lampang was made temporary capital. It was Rama I (of the present Chakri Dynasty) who re-established the city after several skirmishes with the Burmese. The Thai commander, Kawila, was given the title "Prince of Chiang Mai" for his valiant efforts. Chiang Mai has remained a part of Thailand (Siam) ever since despite frequent Burmese raids. Around this time Chiang Saen was under siege by Thai forces attempting to starve out the Burmese occupiers. The Thai army did not succeed and retreated fearing a Burmese counter-attack. Meanwhile the residents revolted slaying the Burmese troops and opening the city gates for their liberating compatriots to enter.

Rama I ordered the destruction of Chiang Saen in 1804 to prevent the Burmese from using it as a springboard to attack Chiang Mai. He did likewise to the surrounding Shan states towns (now in Burma and Laos). With Chiang Saen in flames the 23,000 residents were sent to populate Chiang Mai, Lampang and Nan which is why, even today, the town of Chiang Saen is little more than a village. Skirmishes, uprising and wars were an integral part of daily life in Lan Na during these times and it would require much more space than we have here to cover many of the past conflicts.

When Lan Na recovered it was part of a different world. The new dynasty of Chao Kawila was helped to dominance by Bangkok and, for the first time, Chiang Mai became a tributary state. But the economy remained oriented to Burma. The key trade route ran dwn the Salween River to Moulmein, and the currency was rupees. The Lan Na tried to manipulate these cross-cutting ties to preserve some independence. But as Burma succumbed to Britain during the 19th century, their economic links became bound into British colonialism first through trade, and then logging. Lan Na found itself in the cross hairs of the competing territorial ambitions of Britain, France and Siam...Siam’s takeover of Lan Na during the Fifth reign (1868-1910) has the smack of colonialism. Governors arrived at the head of troop columns and were annoyed the locals could not speak Thai, They bought off the old elite with money, and flattened peasant resistance bullets. They taxed everything they could, and reoriented trade from the Salween to the Chao Phraya....The Yuan language and Shan script went into steep decline. Monks were pried away from old traditions. Burmese and Shan traders were ousted by Chinese. The local nobility disappeared. The auspicious political centre of Chiang Mai was built over by a collection of drab government offices.” The last ruler of Chiang Mai with Northern connections was Chao Keo Naovarat. A Bangkok appointed governor replaced him in 1939. A bridge, connecting the east of the city with the old city is named in his honor.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Tourist Authority of Thailand, Thailand Foreign Office, The Government Public Relations Department, CIA World Factbook, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2020