SIR THOMAS RAFFLES LANDS IN SINGAPORE

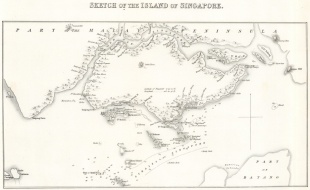

Concerned that Britain lacked a major port between China and India, the British explorer and merchant Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) scouted various locations in Southeast Asia for such a port. In 1819, Raffles explored what is now a Singapore and decided it was the perfect place to establish a port because it was a about halfway between the ports of India and China and it was situated on the Malacca Straits, an important shipping lane on which nearly all ships traveling between India and China and between Europe and the Far East passed.

Raffles was the Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) in Sumatra. He landed in Singapore on January 29, 1819, after a survey of the neighbouring islands. Recognising the immense potential of the island, he helped negotiate a treaty with the local rulers, establishing Singapore as a trading station. Soon, the island’s policy of free trade attracted merchants from all over Asia and from as far away as the U.S. and the Middle East. At the time Raffles arrived Singapore was covered by rainforests and swamps. The only inhabitants were 150 or so Malays. Raflles was determined that Singapore be an entrepot and free port, concentrating on providing services for commerce and shipping. Later Rafffles wrote: "The Settlement I had the satisfaction to form in this very centrical and commanding station has had every success ... our Port is already crowded with shipping from all the native Ports in the Archipelago."

In 1817, Raffles set off to find a suitable port site in the Strait of Malacca. Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar wrote in Archaeology magazine: The opium trade with China was growing, and Raffles was determined to build a British base in the region. In 1819, he lit upon a small island at the southern end of the strait, off the tip of Malaysia — an unremarkable settlement that he nonetheless believed was both strategically located and possessed of a glorious history. [Source: Vaishnavi Chandrashekhar, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

Raffles’ conviction about the island’s illustrious past came from reading his copy of the Malay Annals, a fifteenth-century narrative about the Malay kingdoms. According to this account, a Sumatran prince was out hunting on a hill when he spied a blinding white shore across the sea, a land he learned was called Temasek. On sailing over, he spotted what seemed to be a lion, and so named his new kingdom Singapura, or “Lion City” in Sanskrit. He ruled there for many years, as did his descendants after him, during which time, the Annals tell us, “Singapura became a great city, to which foreigners resorted in great numbers so that the fame of the city and its greatness spread through the world.” Eventually, this great Malay port was conquered by the Javanese and its king forced to flee north to Melaka.

Raffles, hundreds of years later, saw evidence on the island for the tale: the remains of a fortified wall and what locals called Forbidden Hill, said to conceal the graves of kings. Raffles negotiated with the local sultanate to develop the settlement, and wrote to his patroness, Princess Charlotte, that he had planted the British flag on “the site of the ancient maritime capital of the Malays.” Within a few years, a sleepy settlement had turned into a bustling port, the most important in the region.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SINGAPORE HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF SINGAPORE: LEGENDS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND 14TH CENTURY TRADE factsanddetails.com

ORANG LAUT— SEA NOMADS OF MALAYSIA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE GROWS AND PROSPERS IN THE 19TH CENTURY: TRADE, THE BRITISH, IMMIGRANTS factsanddetails.com

CHINESE, MALAYS AND INDIANS IN EARLY SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPAN'S MALAYA CAMPAIGN AND DEFEAT OF THE BRITISH IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE INVASION OF SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com

SINGAPORE DURING WORLD WAR II: POOR BRITISH DEFENSE, HARSH JAPANESE OCCUPATION factsanddetails.com

Life and Career of Sir Thomas Raffles

The son of an impoverished ship captain, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles began his career at an early age as a clerk for the British East India Company in London. He was promoted at the age of twenty-three to assistant secretary of the newly formed government in Penang in 1805. He was serious student of the history and culture of the region and became fluent in Malay. His achievements as an administrator in Penang earned him an appointment as Lieutenant Governor of Java (1811-1816), temporarily under British control after the Napoleonic Wars. After falling out with the company for making reforms to the Dutch colonial system, Raffles returned to England.

Raffles returned to Southeast Asia as governor of Bengkulu on the southwestern coast of Sumatra. The search that resulted in the founding of Singapore began after he convinced the British governor general in India of the importance of the Malacca Strait and the need to set up an outpost there to counteract Dutch expansionism in the area.

Raffles vigorously opposed his government's plan to abandon control of the China trade to the Dutch. In 1818 Raffles sailed from Bencoolen to India, where he convinced Governor General Lord Hastings of the need for a British post on the southern end of the Strait of Malacca. Lord Hastings authorized Raffles to secure such a post for the British East India Company, provided that it did not antagonize the Dutch. Arriving in Penang, Raffles found Governor General James Bannerman unwilling to cooperate. When he learned that the Dutch had occupied Riau and were claiming that all territories of the sultan of Johore were within their sphere of influence, Raffles dispatched Colonel William Farquhar, an old friend and Malayan expert, to survey the Carimon Islands (modern Karimun Islands near Riau). Disregarding Bannerman's orders to him to await further instructions from Calcutta, Raffles slipped out of Penang the following night aboard a private trading ship and caught up with Farquhar. Raffles knew of Singapore Island from his study of Malay texts and determined to go there. [Source: Library of Congress]

Purchase Singapore from the Sultan of Johore

When Rafflaes at Singapore it was owned by the Sultan of Johore, who agreed to sell part of it to the British East India Company. Johore was the Malay state at the extreme southern end of the Malay peninsula. According to the agreement, British jurisdiction would extend over a limited part of the island. In 1824, the island was ceded outright to the company by the Sultan of Johore, In 1826, it was incorporated with Malacca (Melaka, Malaysia) and Penang (Pinang, Malaysia) to form the Straits Settlements

The treaty was concluded between the British East India Company and the sultan of Johore stated "the island of Singapore together with the adjacent seas, straits and islets to the extent of 10 geographical miles from the coast of Singapore were given up in full sovereignty and property to the English East India Company." [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

For the first years of its founding, Singapore was one of the dependencies of Bencoolen. The city subsequently came under the control of the Bengal government and thereafter in 1826 was incorporated with Penang and Malacca to form the Straits Settlements under the control of British India. Although containing only a small fishing and trading village, Singapore quickly attracted Chinese and Malay merchants. The port grew rapidly, soon overshadowing Penang and Malacca in importance. By 1832 Singapore had become the center of government for Singapore, Penang and Malacca. On April 1, 1867, the Straits Settlements became a crown colony under the jurisdiction of the colonial office in London.[Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Raffles and the Establishment of Singapore

On January 28, 1819, Raffles and Farquhar anchored near the mouth of the Singapore River. The following day the two men went ashore to meet Temenggong Abdu'r Rahman, who granted provisional permission for the British East India Company to establish a trading post on the island, subject to the approval of Hussein. Raffles, noting the protected harbor, the abundance of drinking water, and the absence of the Dutch, began immediately to unload troops, clear the land on the northeast side of the river, set up tents, and hoist the British flag. Meanwhile, the temenggong sent to Riau for Hussein, who arrived within a few days. Acknowledging Hussein as the rightful sultan of Johore, on February 6 Raffles signed a treaty with him and the temenggong confirming the right of the British East India Company to establish a trading post in return for an annual payment (in Spanish dollars, the common currency of the region at the time) of Sp$5,000 to Hussein and Sp$3,000 to the temenggong. Raffles then departed for Bencoolen, leaving Farquhar in charge, with instructions to clear the land, construct a simple fortification, and inform all passing ships that there were no duties on trade at the new settlement. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The immediate reaction to Raffles' new venture was mixed. Officials of the British East India Company in London feared that their negotiations with the Dutch would be upset by Raffles' action. The Dutch were furious because they considered Singapore within their sphere of influence. Although they could easily have overcome Farquhar's tiny force, the Dutch did not attack the small settlement because the angry Bannerman assured them that the British officials in Calcutta would disavow the whole scheme. In Calcutta, meanwhile, both the commercial community and the Calcutta Journal welcomed the news and urged full government support for the undertaking. Lord Hastings ordered the unhappy Bannerman to provide Farquhar with troops and money. Britains foreign minister Lord Castlereagh, reluctant to relinquish to the Dutch "all the military and naval keys of the Strait of Malacca," had the question of Singapore added to the list of topics to be negotiated with the Dutch, thus buying time for the new settlement. *

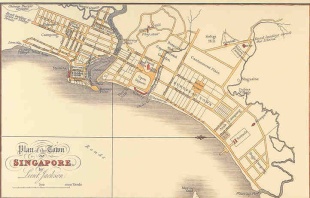

The opportunity to sell supplies at high prices to the new settlement quickly attracted many Malacca traders to the island. Word of Singapore's free trade policy also spread southeastward through the archipelago, and within six weeks more than 100 Indonesian interisland craft were anchored in the harbor, as well as one Siamese and two European ships. Raffles returned in late May to find that the population of the settlement had grown to nearly 5,000, including Malays, Chinese, Bugis, Arabs, Indians, and Europeans. During his four-week stay, he drew up a plan for the town and signed another agreement with Hussein and the temenggong establishing the boundaries of the settlement. He wrote to a friend that Singapore "is by far the most important station in the East; and, as far as naval superiority and commercial interests are concerned, of much higher value than whole continents of territory." *

At this time, Singapore had about 1,000 inhabitants. David Lamb wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Singapore, then just a pimple on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, was a swampy fishing and trading village when Raffles arrived. It had few people, no resources and no relief from the blistering heat. But like all valuable real estate, it had three key attributes: location, location, location. "The City of the Lion" stood at the crossroads of the Orient, amid the Strait of Malacca and the shipping lanes that link the lands of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Like Hong Kong and Gibraltar, it would become a cornerstone of Britain's empire, and its port would eventually become one of the world's busiest. [Source: David Lamb, Smithsonian magazine, September 2007]

Singapore Under Raffle’s Plan and Administration

When Raffles returned to Singapore from Bencoolen in October 1822, he immediately began drawing up plans for a new town. An area along the coast about five kilometers long and one kilometer deep was designated the government and commercial quarter. A hill was leveled and the dirt used to fill a nearby swamp in order to provide a place for the heart of the commercial area, now Raffles Place. An orderly and scientifically laid out town was the goal of Raffles, who believed that Singapore would one day be "a place of considerable magnitude and importance." Under Raffles' plan, commercial buildings were to be constructed of brick with tiled roofs, each with a two-meter covered walkway to provide shelter from sun and rain. Spaces were set aside for shipyards, markets, churches, theaters, police stations, and a botanical garden. Raffles had a wooden bungalow built for himself on Government Hill. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Each immigrant group was assigned an area of the settlement under the new plan. The Chinese, who were the fastest growing group, were given the whole area west of the Singapore River adjoining the commercial district; Chinatown was further divided among the various dialect groups. The temenggong and his followers were moved several kilometers west of the commercial district, mainly in an effort to curtail their influence in that area. The headmen or kapitans of the various groups were allotted larger plots, and affluent Asians and Europeans were encouraged to live together in a residential area adjacent to the government quarter. *

In the absence of any legal code, Raffles in early 1823 promulgated a series of administrative regulations. The first required that land be sold on permanent lease at a public auction and that it must be registered. The second reiterated Singapore's status as a free port, a popular point with the merchants. In his farewell remarks, Raffles assured them that "Singapore will long and always remain a free port and no taxes on trade or industry will be established to check its future rise and prosperity." The third regulation made English common law the standard, although Muslim law was to be used in matters of religion, marriage, and inheritance involving Malays. *

Raffles was an enlightened administrator for his time. He believed in the prevention of crime and the reform, rather than the mere punishment, of criminals. Payment of compensation to the injured by the offender was to be considered as important as punishment. Only murder was to be considered a capital offense, and various work and training programs were used to turn prisoners into useful settlers. Raffles shut down all gambling dens and heavily taxed the sale of liquor and opium. He abolished outright slavery in 1823, but was unable to eradicate debt bondage, by which immigrants often were forced to work years at hard labor to pay for their passage. *

Raffles felt that under Farquhar the temenggong and the sultan had wielded too much power, receiving one-third of the proceeds from the opium, liquor, and gambling revenues, and demanding presents from the captains of the Asian ships that dropped anchor there. Hussein and the temenggong, however, viewed Singapore as a thriving entrepôt in the mold of the great port cities of the Malay maritime empires of Srivijaya, Malacca, and Johore. As rulers of the island, they considered themselves entitled to a share of the power and proceeds of the settlement. In June 1823, Raffles managed to persuade Hussein and the temenggong to give up their rights to port duties and their share in the other tax revenues in exchange for a pension of Sp$1,500 and Sp$800 per month, respectively.

Because the Dutch still contested the British presence in Singapore, Raffles did not dare push the issue further. On March 17, 1824, however, the AngloDutch Treaty of London was signed, dividing the East Indies into two spheres of influence. The British would have hegemony north of a line drawn through the Strait of Malacca, and the Dutch would control the area south of the line. As a result, the Dutch recognized the British claim to Singapore and relinquished power over Malacca in exchange for the British post at Bencoolen. On August 3, with their claim to Singapore secure, the British negotiated a new treaty with the sultan and the temenggong, by which the Malay rulers were forced to cede Singapore and the neighboring islands to the British East India Company for cash payments and increased pensions. Under the treaty, the Malay chiefs also agreed to help suppress piracy, but the problem was not to be solved for several more decades. *

In October 1823, Raffles left Singapore for Britain, never to return. Before leaving, he replaced Farquhar with the Scotsman John Crawfurd, an efficient and frugal administrator who guided the settlement through three years of vigorous growth. Crawford continued Raffles' struggles against slavery and piracy, but he permitted the gambling houses to reopen, taxed them, and used the revenue for street widening, bridge building, and other civic projects. He failed to support, however, Raffles' dream of higher education for the settlement. As his last public act, Raffles had contributed Sp$2,000 toward the establishment of a Singapore Institution, which he had envisioned as a training ground for Asian teachers and civil servants and a place where European officials could gain an appreciation of the rich cultural heritage of the region as Raffles himself had. He had hoped that the institution would attract the sons of rulers and chiefs of all the region. Crawfurd, however, advised the company officials in Calcutta that it would be preferable to support primary education. In fact, education at all levels was neglected until much later. *

Early Days of British-Controlled Singapore

Singapore ultimately prospered in its role as a free-trade hub for Southeast Asia, but the early years, according to to Lonely Planet “were marred by bad sanitation, disease, Empire-sponsored opium addiction and piracy.” Large-scale immigration of Chinese workers occurred, with some Chinese intermarrying with local Malays to create the Peranakan people and culture. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Although the India-China trade was partly responsible for the overnight success of Singapore, even more important was the well-established entrepôt trade of the East Indies that the new port captured from Riau and other trade centers. The news of the free port brought not only traders and merchants but also permanent settlers. Malays came from Penang, Malacca, Riau, and Sumatra. Several hundred boatloads of Hussein's followers came from Riau, and the new sultan had built for himself an istana (palace in Malay), thus making Singapore his headquarters. The growing power of the Dutch in Riau also spurred several hundred Bugis traders and their families to migrate to the new settlement. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Singapore was also a magnet for the Nanyang Chinese who had lived in the region for generations as merchants, miners, or gambier farmers. They came from Penang, Malacca, Riau, Manila, Bangkok, and Batavia to escape the tariffs and restrictions of those places and to seek their fortunes. Many intermarried with Malay women, giving rise to the group known as the Baba Chinese. The small Indian population included both soldiers and merchants. A few Armenian merchants from Brunei and Manila were also attracted to the settlement, as were some leading Arab families from Sumatra. Most Europeans in the early days of Singapore were officials of the British East India Company or retired merchant sea captains. *

Not wanting the British East India Company to view Singapore as an economic liability, Raffles left Farquhar a shoestring budget with which to administer the new settlement. Prevented from either imposing trade tariffs or selling land titles to raise revenue, Farquhar legalized gambling and the sale of opium and arak, an alcoholic drink. The government auctioned off monopoly rights to sell opium and spirits and to run gambling dens under a system known as tax farming, and the revenue thus raised was used for public works projects. Maintenance of law and order in the wideopen seaport was among the most serious problems Farquhar faced. There was constant friction among the various immigrant groups, particularly between the more settled Malays and Chinese from Malacca and the rough and ready followers of the temenggong and the sultan. The settlement's merchants eventually funded night watchmen to augment the tiny police force. *

Why Singapore’ was Important to the British

The establishment of Singapore was driven largely by the need to safeguard the China trade of the English East India Company and its private agents. This trade centred on the exchange of tea from Canton (modern-day Guangzhou) for opium produced in Bengal. Commerce between Europe, India, Southeast Asia, and China moved primarily along two maritime corridors: the Straits of Malacca to the north and the Straits of Sunda to the south. While the southern passage remained under Dutch control, the British founding of Penang at the northern entrance to the Straits of Malacca in 1781, followed by Singapore in 1819, brought both gateways under British influence. This effectively ensured British dominance over the China trade. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Anglo-Dutch rivalry during the second quarter of the nineteenth century kept political arrangements unsettled, yet Singapore prospered amid this uncertainty. Its rapid success encouraged Britain to insist on retaining the settlement in negotiations that culminated in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1825. The treaty formalised a division of spheres of influence: the British took control of the northern sector of the Straits of Malacca, while the Dutch retained the southern portion. By then, Singapore had already become a favoured port for British private traders, who, after the opening of the India trade in 1813, had begun to engage extensively in commerce with China.

Singapore soon emerged as an important transshipment centre. European merchants collected Chinese silks there, while British textiles were deposited for onward shipment to China by Chinese traders. This intermediary role diminished after 1833, when the China trade was fully liberalised. Nevertheless, Singapore’s designation as a free port had already laid the foundations for extraordinary growth, both regionally and within an expanding global trading network.

In 1827, George Windsor Earl, a British colonial official and ethnographer, offered a vivid assessment of Singapore following his travels through Java, Borneo, the Malay Peninsula, and Siam. He noted that Singapore’s position at the tip of the Malay Peninsula enabled communication between the China Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Beyond European commerce, he observed, traders from across the world were drawn by the absence of duties, exchanging Indian manufactures for the rich products of the archipelago. Ships of many nations crowded the harbour, where British, Dutch, French, and American flags flew alongside the banners of Chinese junks and the brightly coloured sails of native prahus.

Earl’s account was both perceptive and precise. His description captured the astonishing pace of Singapore’s growth within a decade of its founding and hinted at the vast possibilities that lay ahead. From the outset, Singapore was conceived as a free port, a defining feature that fuelled its rapid rise and enduring commercial significance.

Pirates and Triads in Early Singapore

Probably the most serious problem facing Singapore at midcentury was piracy, which was being engaged in by a number of groups who found easy pickings in the waters around the thriving port. Some of the followers of the temenggong's son and heir, Ibrahim, were still engaging in their "patrolling" activities in the late 1830s. Most dangerous of the various pirate groups, however, were the Illanun (Lanun) of Mindanao in the Philippines and northern Borneo. These fierce sea raiders sent out annual fleets of 50 to 100 well-armed prahu, which raided settlements, attacked ships, and carried off prisoners who were pressed into service as oarsmen. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

The Illanun attacked not only small craft from the archipelago but also Chinese and European sailing ships. Bugis trading captains threatened to quit trading at Singapore unless the piracy was stopped. In the 1850s, Chinese pirates, who boldly used Singapore as a place to buy arms and sell their booty, brought the trade between Singapore and Cochinchina to a standstill. The few patrol boats assigned by the British East India Company to protect the Straits Settlements were totally inadequate, and the Singapore merchants continually petitioned Calcutta and London for aid in stamping out the menace. *

By the late 1860s, a number of factors had finally led to the demise of piracy. In 1841, the governor of the Straits Settlements, George Bonham, recognized Ibrahim as temenggong of Johore, with the understanding that he would help suppress piracy. By 1850 the Royal Navy was patrolling the area with steam-powered ships, which could navigate upwind and outmaneuver the pirate sailing ships. The expansion of European power in Asia also brought increased patrolling of the region by the Dutch in Sumatra, the Spanish in the Philippines, and the British from their newly established protectorates on the Malay Peninsula. China also agreed to cooperate in suppressing piracy under the provisions of treaties signed with the Western powers in 1860. *

In addition, Chinese secret societies (some of which later evolved in Triads) flourished, and violent crime was a fact of life in the early decades of British-controlled Singapore. Thomas Dunman, Singapore's first superintendent of police, was a young British merchant who was respected by leaders of the European community and supported by influential Malays and Indians, who felt powerless to prevent Chinese gangs from roving into their districts, assaulting people, and robbing homes and businesses. In 1843 Dunman recruited a small group of itinerant workers and single-handedly trained and organized them into an effective police force. By 1856 gang robberies no longer were a major problem, but the secret societies continued to control lucrative gambling, drug, and prostitution operations. *

British Military and Police in Singapore in the Early 1800s

In the years preceding the founding of Singapore in 1819, neither the British government nor the British East India Company was eager to risk the establishment of new settlements in Southeast Asia. From 1803 to 1815, London was preoccupied with war with France and, after Napoleon's abdication in October 1815, with establishing a stable peace in Europe. Britain administered the Dutch colonies in Malaya and Indonesia from 1795 to 1815 when the Netherlands was under French occupation. The British government returned control of these territories to the Dutch in 1816 over the objections of a small minority of British East India Company officials, including Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987*]

Raffles, in London from 1816 to 1818, failed to convince the directors of the British East India Company to support a plan to challenge Dutch supremacy in the Malay Archipelago and Malaya. Enroute from London to Malaya, however, Raffles stopped in India and gained the support of Lord Hastings, the British East India Company's governor general of India, for a less ambitious plan. They agreed to establish a trading post south of Britain's settlement in Penang, Malaya.*

From 1819 to 1867, when Singapore was administered by the British East India Company, Britain relied on its navy to protect its interests there and in Malaya. The Netherlands was the only European country to challenge the establishment of Singapore. In 1824, however, the Dutch ceded Malacca on the Malay Peninsula to Britain and recognized the former's claim to Singapore in exchange for British recognition of Amsterdam's sovereignty over territories south of the Singapore Strait. Two years later, the British East India Company united Singapore with Malacca and Penang to form the Presidency of the Straits Settlements. With no threat to its interests, the British employed the policy of allowing Singapore to assume responsibility for its own defense, although British naval vessels called in Singapore to show the flag and to protect shipping in the Singapore Strait.

Between 1819 and 1867, the British East India Company worked closely with citizens' councils that represented the European, Chinese, Malay, and Indian communities to maintain law and order in Singapore. The British civil service comprised a small and overworked staff that often tried unsuccessfully to enforce British laws in the Straits Settlements. The resident councillor for Singapore was responsible for adjudicating most criminal and civil cases. More serious cases were referred to the governor of the Straits Settlements in Penang, or, on rare occasions, to the governor general in India.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Singapore Tourism Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026