RADIATION RELEASED FROM FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT

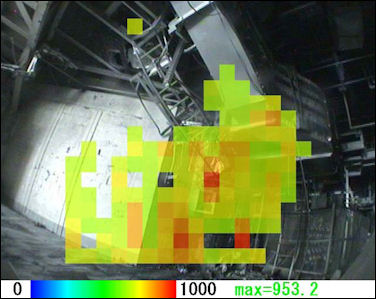

radiation map of a Fukushima reactor The total amount of radiation discharged from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant is one-sixth of the estimated 5.2 million tera-becquerels emitted in the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, TEPCO said. The amount of radioactive material that leaked into the environment from the Nos. 1 to 3 reactors in the five days following the March 11 disaster is estimated at 900,000 terabecquerels. Radiation amounts released after those five days was considerably less, the utility said. One terabecquerel is equal to 1 trillion becquerels. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 26, 2012]

“The amount of radioactive material discharged as a result of the hydrogen explosion at the No. 1 reactor building on March 12 and at the No. 3 reactor building on March 14 was relatively small at 5,000 terabecquerels and 1,000 terabecquerels, respectively, the report said. Radioactive emissions from steam venting operations carried out to relieve pressure within the No. 1 and No. 3 containment vessels were also relatively small at a total of about 1,400 terabecquerels, it said.

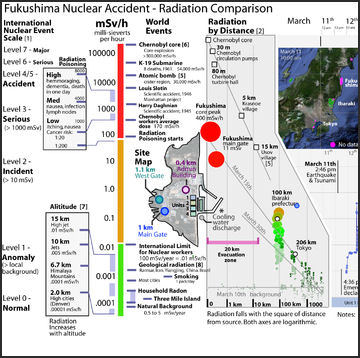

No one, including personnel who worked in the buildings at Fukushima nuclear power plant, died from radiation exposure. Robert Peter Gale and Eric Lax wrote in Bloomberg, “Why are the anticipated risks from Japan’s nuclear accident so small? Perhaps the most important reason is that about 80 percent of the radiation released was blown into the ocean. Radioactive contamination of the sea sounds dreadful, but because oceans naturally contain large amounts of radioactive materials, the net increase in oceanic radioactivity is minuscule. Another reason the public was protected is that the 200,000 or so people living within 15 miles of Fukushima were rapidly evacuated. People living in a few hotspot towns slightly farther away who didn’t leave on their own received the highest civilian doses. [Source: Robert Peter Gale & Eric Lax, Bloomberg, March 10, 2013. Robert Peter Gale, a visiting professor of hematology at Imperial College London, has for 30 years been involved in the global medical response to nuclear and radiation accidents. He helped victims at Chernobyl. Eric Lax is a writer and author of “Radiation: What It Is, What You Need to Know.”]

Links to Articles in this Website About the 2011 Tsunami and Earthquake factsanddetails.com : MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI IN JAPAN: DEATH TOLL AND ITS BEGINNING factsanddetails.com ; ARTICLES ABOUT THE CRISIS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DAMAGE FROM 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER AFTER THE MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI factsanddetails.com ; MELTDOWNS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HOURS OF THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com ; TEPCO AND THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER: SHODDY SAFETY MEASURES, THE YAKUZA AND POOR MANAGEMENT factsanddetails.com ; JAPANESE GOVERNMENT'S HANDLING OF THE TSUNAMI AND THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com ; BRAVE WORKERS AND ROBOTS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT factsanddetails.com ; RADIOACTIVE WATER CONTAINMENT AT FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT factsanddetails.com COLD SHUTDOWN AND LONGER TERM MANAGEMENT OF FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR CRISIS factsanddetails.com ; RADIATION RELEASES, FEARS AND HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com

Distribution and Types of Radiation Released by the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plants

“A breakdown of radioactive emissions showed that short-lived iodine-131 stood at 500,000 terabecquerels, while cesium amounted to 400,000 terabecquerels in iodine equivalents, the report said. Emissions from the Nos. 2 and 3 reactors accounted for about 40 percent and 20 percent, respectively, of the total, according to the report. TEPCO said there were no significant leaks from No. 4 reactor, which had been halted for regular maintenance at the time of the disaster, as spent nuclear fuel stored in its fuel pool was not subject to any serious damage from the March 11 earthquake and tsunami. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 26, 2012]

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: The impact of a nuclear accident depends, to an extraordinary degree, on luck — not only on the fateful actions of workers in a crisis but on the direction of the wind. For four days after the meltdown, the wind blew out to sea. But then it swung sharply around and turned to the northwest. To make matters worse, there was rain and snow, which captured radioactive particles in the air and drove them deep into Fukushima’s mountain forests and streams. For days, the government stayed silent about where the fallout was going. Leaders were “afraid of triggering a panic,” Goshi Hosono, the minister in charge of the crisis, has said. It was unwise; some evacuees fled into the plume, a mistake that has prompted one local mayor to accuse the government of murder. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 17, 2011]

Radioactive barium, cesium, iodine and tellurium were detected March 16 in a radiation plume released by damaged nuclear reactors at Fukushima. A partly dispersed cloud passed by the Tokyo area the same day, Austria’s Meteorological and Geophysics Center reported. In June 2011 Japan's nuclear safety agency said the amount of radiation that leaked from Fukushima Daiichi in the first week of the accident may have been more than double that initially estimated by Tepco.

radiation suits How bad is the Fukushima fallout? According to an article in Yomiuri Shimbun, “Fallout of cesium-137 has been monitored for every 24-hour period since March 18 at observation points in each prefecture, except quake-hit Fukushima and Miyagi. Cesium-137 is an international indicator for radioactive contamination. Monitoring data has shown the total fallout of cesium-137 in Hitachinaka, Ibaraki Prefecture, for 18 days through Tuesday morning was 26,399 becquerels per square meter. In Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo, the figure was 6,615 becquerels per square meter. Rain on March 21-22--the first since the nuclear crisis began--brought down a large amount of cesium-137, spreading the contamination to Tokyo and 13 prefectures in and around the Kanto region.”

In October 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported, plutonium believed to have been released from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant after the March 11 earthquake was founded in six locations. A map released by the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry on shows plutonium was found in soil samples taken from six locations in Futabamachi, Namiemachi and Iitatemura, Fukushima Prefecture. One of the spots is 45 kilometers from the plant. However, a ministry official said because amounts of both substances were very small, decontamination efforts should focus on radioactive cesium.

Strontium-89 and strontium-90, both believed to have been released from the power plant, were detected at 45 spots. The maximum quantity of strontium-90, whose half-life of about 29 years is much longer than the approximately 50-day half-life of strontium-89, was 5,700 becquerels per square meter detected in Futabamachi. This is six times that of the maximum quantity of 950 becquerels found before the Fukushima plant accident.

No. 2 Reactor Source of Most of the Radiation

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Tokyo Electric Power Co. has revealed that the damaged containment vessel of the No. 2 reactor at its Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant was the main source of radiation contamination in Iitate and neighboring areas in northeastern Fukushima Prefecture. The damaged No. 2 reactor's containment vessel released an estimated 160,000 terabecquerels of radioactive substances on March 15, causing the soil in surrounding areas to become heavily contaminated, TEPCO said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 26, 2012]

“TEPCO's estimates covered the period from March 12 to March 31. Radioactive emissions after the beginning of April were considered less than 1 percent of those in March and were not included in the latest estimates, the utility said. TEPCO arrived at the estimate by reverse calculating data such as radiation readings taken at the crippled nuclear plant. Radiation sources were also determined by examining changes in reactor steam pressure, the company said.

“There is a high probability that pressure inside the No. 2 reactor's containment vessel rose to 1.5 times the designated maximum in the early hours of March 15, causing damage to seams and other parts of the vessel, it said. A southeasterly wind later that afternoon, followed by rain in the evening, contributed to the heavy soil contamination in and around Iitate, the company said.

“Radioactive emissions from the nuclear power plant registered a maximum level of 180,000 terabecquerels the day after the disaster. However, it is considered to have diffused into the atmosphere as there was no rainfall that day, TEPCO said.Pressure inside the No. 3 reactor's containment vessel declined by more than one-third on March 15 and 16, indicating a massive amount of radioactive steam may have leaked out of the damaged vessel during the two days, the utility's report said.

Areas with High Levels of Radiation

place with high radiation levels The worst radiation readings were taken northwest of the Fukushima nuclear power plant on the sides of mountains and hills facing the plant apparently because winds blew radiation in that direction after the most intense concentrations of radiation were released during the hydrogen explosions and were brought to the ground by the mountains and weather systems around the mountains.

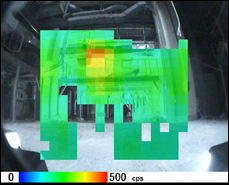

Radiation readings taken in mid April recorded: 1) 110 microsieverts per hour within three kilometers of the Fukushima nuclear power plant: 2) 31.5 microsieverts per hour at Katsuaomura 20 kilometers northwest of the Fukushima plant; 3) 29.8 microsieverts per hour at Namiemachi 19 kilometers northwest of the plant; 4) 1.15 microsieverts per hour at Tamura 19 kilometers west of the plant; 5) 3.54 microsieverts per hour at Okumamachi eight kilometers southwest of the plant; and 6) 16 microsieverts per hour at Tomiokamachi 10 kilometers south of the plant.

Traces of radioactive material were detected in the breast milk of women in the Tokyo area and the area hit by earthquake and tsunami but the levels were far below levels that would be considered a health risk. A Japanese government health official said, “The levels defected wouldn’t harm the health of the mothers or their infants, so they can keep breast-feeding as normal.”

Even in places where radiation readings were relatively low, schools kept their students indoors out of concern they would be exposed to radiation. As part of the effort to reduce radiation earth movers and workers were brought in remove soil contaminated with radioactivity.

In May the education ministry has estimated children who attend schools in Fukushima Prefecture where radiation exceeds government limits but restrict their outdoor activities will be exposed to about 10 millisieverts of radiation a year, less than the annual limit set by the government due to the nuclear crisis.

In mid June, Fukushima city began conducting extensive surveys of radiation levels all over the city with spot checks by hand-held radiation-measuring devices often done on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis with the results shown immediately to residents. Sometimes there were high readings in unexpcted places. In late June health checks began for all 2 million or so of Fukushima Prefecture’s residents, with plans for follow ups to continue for more than 30 years.

Fatal Radiation Level Found at Japanese Plant

In late July 2011, TEPCO said it measured the highest radiation levels within the plant since it was crippled by a devastating earthquake. However, it said the discovery would not slow continuing efforts to bring the plant’s damaged reactors under control. [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 1, 2011]

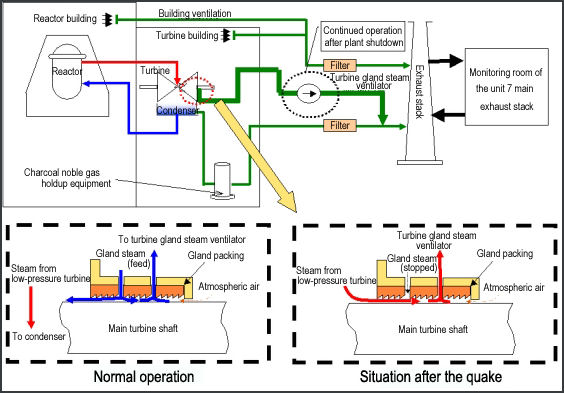

TEPCO said it had found an area near Reactors No. 1 and 2, where radiation levels exceeded their measuring device’s maximum reading of 10 sieverts (10,000) per hour — a fatal dose for humans. The company said the reading was taken near a ventilation tower, suggesting that the contamination happened in the days immediately after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami, when workers desperately tried to release flammable hydrogen gas that was then building up inside the reactor buildings.

gravel with high radiation levels The Yomiuri Shimbun reported the record-high radiation levels were detected on a pipe at the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant and exposure to radiation of that level for just six minutes would be enough to cause nausea and other acute symptoms. According to TEPCO, the pipe connects the containment vessels of the Nos. 1 and 2 reactors to a main exhaust stack. No work was scheduled to be conducted in the area, and TEPCO has prohibited anyone from coming within three meters of the pipe. The previously highest level detected at the plant was 4 sieverts per hour inside the No. 1 reactor building. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 2011]

TEPCO said workers noticed the high radiation levels Sunday while using a camera that detects gamma rays to check the area from some distance away. The three workers who measured the radiation were exposed to up to 4 millisieverts per hour, the utility said. The company said the workers who found the reading were safely protected by antiradiation clothing. TEPCO said this would not hamper efforts to build a new cooling system and remove contaminated water.

Junichi Matsumoto, acting director of TEPCO's Nuclear Power and Plant Siting Division, said the pipe might have been "hot" since the day after the March 11 quake and tsunami knocked out the plant's cooling functions. "It's possible that radioactive substances released when the No. 1 reactor vents were opened on March 12 might have accumulated inside the pipe," Matsumoto said Monday.

However, Kenzo Miya, a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo and an expert in nuclear engineering, suggested another possible explanation. He told the Yomiuri Shimbun, "As well as radiation spilling out when the vents were opened, we can't rule out that radioactive substances poured into the pipe during the hydrogen explosion" that damaged the reactor on March 12. "Radiation levels also could be high in the exhaust stacks of the Nos. 3 and 4 reactors. This should be closely checked to ensure the safety of workers at the plant," he said.

Distribution of Radiation on Land

Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times, “When radiation is released with gas, as it was at the Japanese reactors, the particles are carried by prevailing winds, and some will settle on the earth. Rain will knock more of the suspended particles to the ground. “There is an extremely complex interaction between the type of radionuclide and the weather and the type of vegetation,” Dr. Ward Whicker of Colorado State University, who developed a model for following food chain, said. “There can be hot spots far away from an accident, and places in between that are fine.” [Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, March 21, 2011]

As much as 50 percent to 90 percent of radioactive cesium on the ground in forested areas as a result of the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant accident is concentrated on fallen leaves and branches, according to measurements by a research team led by Tsukuba University Prof. Yuichi Onda. The discovery indicates it is possible to reduce large amounts of ground radiation by removing fallen forest materials, and likely will become basic data for decontamination measures. Onda said removing fallen leaves would be an effective way of decontaminating forests. "In addition to this, we want the government to consider trimming branches and cutting down trees as decontamination measures," he said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun , September 15, 2011]

Radiation from Fukushima Detected in the United States

decontamination on U.S. Navy ship A United Nations forecast of the possible movement of radioactive plumes coming from Fukushima reactors predicted they would move across the Pacific, touch the Aleutian Islands before hitting Southern California. Health and nuclear experts emphasized that radiation in the plumes would be diluted as they traveled and, at worst, posed extremely minor health risks in the United States, and more likely would be barley detectable.

Small amounts of radioactive sulfur released from Fukushima nuclear power plant were detected in the atmosphere near San Diego on the U.S. West Coast in weeks after the disaster. The amounts were extremely small and posed no health threats.

In September 2011, Kyodo reported: Radioactive cesium that was released into the ocean from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant is likely to flow back to Japan's coast in 20 to 30 years after circulating in the northern Pacific Ocean in a clockwise pattern according to Researchers at the Meteorological Research Institute and the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry . According to the analysis, the cesium is expected to first disperse eastward into the northern Pacific. It will then be carried southwestward before some of it returns to the Japanese coast carried northward by the Japan Current from around the Philippines. [Source: Kyodo, September 15, 2011]

Tests of milk samples taken in Spokane, Washington two weeks after the earthquake and tsunami indicated the presence of radioactive iodine from the Fukushima plant in Japan, but at levels far below those at which action would have to be taken, the Environmental Protection Agency said. Trace amounts of radiation from the Fukushima plant was also picked up at 12 air-monitoring sites around the U.S. These reports alarmed many Americans. In some places there was a run on potassium iodine pills which protect the thyroid gland from radioactive iodine (the drug works by flooding the body with iodine so the thyroid gland doesn’t pick up the radioactive iodine).

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory said in a statement posted on its blog that it is not expecting harmful radioactivity from Japan to reach the United States: We are working with other U.S. government agencies to monitor the situation in Japan — and to monitor for radioactive releases and to be prepared to predict their path. Fortunately, all the available information at this time indicates weather conditions have taken the small releases from the Fukushima reactors out to sea away from the population...And, importantly, given the thousands of miles between Japan and us — including Hawaii, Alaska, the U.S. territories and the U.S. West Coast — we are not expecting to experience any harmful levels of radioactivity here. We would like to repeat — we are not expecting to experience any harmful levels of radioactivity here.”

Americans weren’t the only ones freaked out by the radiation. In South Korea, more than 100 schools canceled or shortened classes over fears that rain falling across the country might include radiation from the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

Most Fukushima Residents Exposed to Modest Amounts of Radiation

high radiation affects film In February 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: About 58 percent of Fukushima Prefecture residents were likely externally exposed to radiation measuring less than 1 millisievert during the first four months of the Fukushima nuclear crisis, according to a survey by the Fukushima prefectural government. The prefectural government released its estimate of the external radiation doses of 10,468 people. The prefecture has a population of about 2 million people. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, February 21, 2012]

Of 9,747 people, excluding workers at the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, 57.8 percent were estimated to have been exposed to levels less than 1 millisievert--which is considered the annual limit of radiation exposure under normal circumstances--during the first four months, according to the survey. The survey found 94.6 percent of residents were considered to have been exposed to less than 5 millisieverts of radiation.

Only two women were estimated to have been exposed to radiation levels exceeding 20 millisieverts. The main reason behind the two women's high exposure level is that the two stayed in the expanded evacuation zone--the area spanning five municipalities beyond a 20-kilometer radius around the power plant--for more than three months. One of the women is thought to have been exposed to 23 millisieverts of radiation, the highest among people who did not work at the nuclear plant.

"In past epidemiological examinations, obvious health effects have not been observed with cumulative doses of 100 millisieverts or less. The results of the survey show the level of radiation exposure will not likely impact residents' health," an official of the prefecture said. Among 1,693 people under 20 years old who were surveyed, one male was estimated to have been exposed to 18.1 millisieverts, but all others were exposed to less than 10 millisieverts. Among workers at the nuclear plant, the highest level was 47.2 millisieverts.

Japanese Government Withheld Information on Radiation Dispersal

radiation air shower There were a series of delays in the release by the Japanese government of information related to the spread of radioactive substances. The government did not release much of the data on radiation spread forecasts computed by its Nuclear Safety Technology Center's computer system. A $300 million system — comprised of the Emergency Response Support System (ERSS) and the Environmental Emergency Dose information (SPEEDI) — that was supposed collect information about the nuclear reactors and predict the volume of radioactive materials released into the environment didn’t work because power to it was cut off.

[Source: Kyodo, April 30, 2011]

Kyodo reported: “The chief of the Meteorological Society of Japan has drawn flak from within the academic society over a request for member specialists to refrain from releasing forecasts on the spread of radioactive substances from the troubled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. In the request posted March 18 on the society's website, Hiroshi Niino, professor at the University of Tokyo, said such forecasts, which he says carry some uncertainty, "could jumble up information about the government's antidisaster countermeasures unnecessarily...The basic principle behind antidisaster measures is to enable people to act on unified reliable information," he said.

The System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose information (SPEEDI) — the government computer system that projects the dispersal of radioactive substances — was designed to pinpoint which areas should be evacuated after a nuclear accident. An interim report released in December 2011 by a government panel investigating the crisis at the Fukushima plant stated the Japanese government initially withheld SPEEDI projections after the Fukushima nuclear crisis erupted, claiming that releasing the data "would cause unnecessary panic." [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 30, 2011]

Overseen by the Education, Science, Culture, Sports and Technology Ministry, SPEEDI estimates where radioactive material will spread based on data, including figures provided by the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) on the amount of radioactive material released. After the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami the ministry decided such data would be unavailable due to the loss of power at the plant following the massive March 11 earthquake. That evening, it began projecting how much radioactive material would leak every hour, on the assumption that one becquerel was released per hour--a figure in line with Nuclear Safety Commission guidelines.

This data was shared with NISA, the commission and the Fukushima prefectural government. However, none of these entities knew how to make maximum use of this information.Residents near the nuclear plant started evacuating on the evening of March 11. On this point, the report says SPEEDI was useful. "[Its projection] was at least effective for determining that residents should evacuate," the report said.

The science ministry, NISA and the commission calculated the projected spread of radioactive material from the crippled plant using SPEEDI. NISA submitted some of SPEEDI's results to the Prime Minister's Office after 1:30 a.m. on March 12. However, as the results were accompanied by documents suggesting the data "were not very reliable," they were not passed to then Prime Minister Naoto Kan.

The ministry came under growing pressure from the media to reveal the SPEEDI results. On March 15, the ministry had made projections for what would happen if all radioactive material was discharged from the nuclear plant. However, it did not release the figures for fear of panicking the public. Eventually, the Prime Minister's Office ordered the commission be put in charge of SPEEDI. However, the commission continued to withhold some data churned out by the system. The ministry received a request to disclose more information on March 24. The ministry, NISA and the commission discussed what data should be made public, and concluded information that was not highly accurate should not be released.

Public Response in the Fukushima Area to the Radiation

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: The local newspaper was running charts of radiation readings regularly, like the weather report. There was also a lot of bad information going around: in a sign of how far public confidence had sunk, people were invoking the Soviet handling of Chernobyl as a standard to aspire to. When I visited a community center that was conducting free radiation checks of food and objects, people arrived with boxes of snow peas, turnips, eggs, and meat. A father whispered that he had secretly swiped a sample of swimming-pool water from his daughters’ school. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 17, 2011]

It was an oppressive combination of stresses: people were drowning in jargon’sieverts and becquerels and half-lives — at the very moment that they were trying to make decisions about their family’s health. Natsuko, a young mother, was among the parents who turned up at the community center. “If we stay here for one year, how much radiation would my son be exposed to?” she asked a social worker who was helping arrange relocations. Natsuko’s husband, a thickset office worker, was seated nearby; their two-year-old son, wearing a cowboy hat, cargo pants, and a tiny cotton facemask with cartoon cars printed on it, sat between them. “Well,” the social worker said, entering numbers into a calculator, “it comes to fourteen millisieverts. Even though the government is giving free checkups, that doesn’t mean you’ll be healthy. If I were the parent of a small child, I would be leaving right now.”

Natsuko’s shoulders slumped. “I didn’t evacuate in March, and I regret that. Is there anything I can do to make up for it?” she asked. Tears appeared on her cheeks. The boy looked at his mother, then his father, then the social worker, and then his mother again. His father scooped him up and they went for a walk. The social worker said, “It’s not too late. Even for two or three months, you should evacuate.”

Fukushima Kids Exercise Indoors

radiation check Yuko Ohiro of AsiaOne wrote: “Making exercise more fun for kids is a goal that has been spreading in Fukushima Prefecture where the length of time that residents spend outdoors must be limited due to the effects of radiation from the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

At a private kindergarten in Koriyama, Tamuramachi Tsutsumi Yochien, there is plenty of equipment for children to play with indoors.In one corridor, children walked along marks that were spaced about 50 centimeters apart on the floor. One of them told the others, "Let's race to see who is the fastest."Banners were hung from the ceiling, and some of the children jumped to try to touch them. Teoshi-guruma (wheelbarrow) is a popular game for exercise where children walk on their hands as teachers lift their ankles. [Source: Yuko Ohiro, AsiaOne, June 1, 2013]

“Kimiko Tsuji, 72, principal of the kindergarten, said, "Because the children have been forced to stay indoors, it's important that adults find ways to encourage them to be active." About 70 per cent of day care centers had restricted their outdoor activities as of last October. Public day care centers in Koriyama have limited outdoor play time to 15 to 30 minutes a day.

“Radiation levels in kindergartens and day care centers for children have been less than the central government's limit of one microsievert per hour. But in light of parents' concerns, some kindergartens still do not allow children to play outdoors. Tamuramachi Tsutsumi Yochien resumed outdoor activities in June 2011, but the time was limited to 20 to 30 minutes a day. To get children to play indoors, the kindergarten bought balls and trampolines. However, in November, a 3-year-old boy broke his leg while jumping on a trampoline. Tsuji expressed regret, saying, "We should have given children the proper amount of exercise while considering their physical fitness, which seems to have declined." Eimi Yonemoto, 39, a mother of a child in the kindergarten's senior class, said: "Before I was worried about the effects of radiation, but now I'm worried about the amount of exercise. I have to get my child to play more at home." Since May, the kindergarten has extended outdoor play time to about one and a half hours a day. Indoor activities will still continue.

Fears and Rumors About Radiation

Evan Osnos write in The New Yorker, “In the vacuum, fantastical stories circulated: that the Emperor and the Empress had been secreted away from the capital to Kyoto, in advance of a nuclear cloud; that a private citizen with a Geiger counter had tested the area around the Fukushima plant and recorded levels of radiation higher than those at Chernobyl. “[Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, March 28, 2011]

Harmful rumors were spread concerning the radiation and the crisis at the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Sports teams refused to come to Japan to play games. Sri Lanka, for example, for example, refused to send its rugby team to a game scheduled to be played in July in Tokyo, four months after the disaster and the International Rugby Board pulled matches involving Tonga, Samoa and Fiji out of Japan.

There were not only rumors that farm produce was contaminated by radiation but also industrial goods. Abut nations restricted imports of things like vehicles and electronic from Japan. Italy and Taiwan checked Japanese industrial goods for radiation. The United States inspected ships that sailed from Japan. In Hong Kong there radiation checks on medicines and cosmetics from Japan. In Belgium radiation test were performed in motor vehicles. None of the check turned up any significant amounts of radiation. In fact many Japanese firms bent over backward to conduct test themselves to make sure exported products were radiation free.

More than 30 country banned agriculture products from Japan. Some countries not only banned the import of produce from around Fukushima nuclear power plant they banned them from all of Japan, en though vegetable and faut from most places in Japan were fine,

radiation protection measures There appeared to be a lot of word-of-mouth rumors about danger posed by eating food from Japan. Japanese restaurants in Hong Kong — including one that had been in business for more than 40 years — were forced to close down because of concerns people had about radiation in food and ocean products from Japan. The International Herald tribune was to issue an apology after it ran an editorial cartoon with Snow White being offered apples by an old hag and asking, “Hey, wait a minute, do you came from Japan.”

At least 4,330 foreign students left Japan or didn’t come due to fears and concerns about earthquakes, tsunamis and radiation. At Sophia University in Tokyo 120 of the 149 students that were supposed to be enrolled for the spring semester and 75 of the 140 students that enrolled in the fall were not in class in April. A liaison officer at the university said, “It seems students have been told by their parents not to go to Japan, although they want to,

Thousands of Chinese students and so-called trainee workers returned home to China. Some experienced the earthquake and were spooked by it. Others had radiations fears. China was the first country to organize mass evacuations, providing transport for at least 3,000 of its citizens from Tokyo and northern Japan last week. Other Chinese simply took off on their own, in some cases paying triple or more the regular airfare to get out in a hurry. But their departures left many businesses in a lurch, suddenly without employees to provide basic labor.

Car Racing and Radiation Fears from the Fukushima Disaster

Twin Motegi, where the 2011 IndyCar race and the MotoGP motorcycle race were scheduled to be held, is only 120 kilometers away from the Fukushima nuclear power plant, where meltdowns occurred after the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in 2011. Not much of deal was made about radiation at Japan’s Formula One Grand prix, which was held at Suzuka in October 2011, which was 500 kilometers from the Fukushima nuclear power plant, compared to Motegi, which is only 120 kilometers away. Formula One drivers did various kinds of promotions to help draw attention and bring in donations of the victims of the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011. McLaren drivers Jenson Button sported a helmet that said “Ichiban“ (“No.1") in Japanese, Button has a Japanese girlfriend and a deep affection for Japan.

MotoGP postponed its April race until October because of concerns stemming from the Fukushima crisis. Motorcycle riders Valentino Rossi and Jorge Lorenzo said they wanted the Moto GP event in Japan to be cancelled because of concerns they had about radiation at the Motegi track which is north of Tokyo but several hundred kilometers south of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. "People are very scared," Rossi, the seven-time champion, told AP, "The problem is, for example, that I don't really know what the real danger is. "Everyone that I know in the paddock thinks the same, that they would prefer not to go to Japan. Let's hope we can reach a consensus and not go." Lorenzo intends to persuade his fellow riders to boycott the race in Motegi, which lies north of Tokyo but several hundred kilometers south of the worst-affected radiation zones in northeastern Japan. "To be asking yourself (for) your entire life if (the radiation) will affect you doesn't sit well with me," the defending world champion said from the Catalunya GP. "I'm going to try to convince as many riders as possible not to run in Japan." He added in El Pais newspaper: "I don't want to go. I'm very young and I don't want to be asking myself if in 20 years I'll have some kind of reaction or if my children will be born with some kind of deformity." [Source: AP, June 4, 2011]

IndyCar went forward with its event. It couldn't run the race on the oval because of safety concerns, so the race was shifted to a road course. In September 2011, Associated Press reported that Indy race car driver Danica Patrick said she is concerned about traveling to Japan for the Sept. 18 IndyCar race at Twin Ring Motegi. "I don't want to make anyone mad, but heck yeah, I'm concerned," Patrick said at Richmond International Raceway. "MotoGP has made a big fuss about going there, and their race got delayed, and is still after ours next weekend. They had a study done that seemed it was relatively safe. The radiation seems OK."

But Patrick said she is concerned about the food and water, as well as the earthquakes that have occurred since the March disaster. She and her husband plan to pack as much food and water as possible. "They say don't eat beef, which probably means don't eat vegetables and fruit," she said. "I read something about nine times the radiation in mushrooms so far out of Fukushima in that area. And there's earthquakes every week. It seems every other week there's a pretty big one." Her only victory in the IndyCar Series came at Japan, in 2008, on the oval track.

French “Fukushima Effect” Joke Angers Japanese

Japan was angered by a joke made by French TV comedian presenter Laurent Ruquier that attributed the success of the Japanese goalie in a soccer game against France to deformations caused by Fukushima radiation. Following Japan's surprise 1-0 victory over France in a game played in France TV station France 2 showed a composite image of goalkeeper Eiji Kawashima with an extra set of arms, blaming the extra limbs — and his excellent performance — on the "Fukushima Effect." [Source: Ryan Bailey, Dirty Tackle, October 16, 2012]

Japanese politicians were upset by the remark, finding it in extremely poor taste. The Guardian reported: “Japan's chief cabinet secretary Osamu Fujimura called Ruquier's remark, a reference to last year's nuclear crisis in Fukushima, "inappropriate". He added that the Japanese Embassy in France had sent a letter of protest to the TV station France 2. The letter said the remark "hurts the feelings of people affected by the disaster and hinders efforts for reconstruction," Fujimura added.

Handheld Decontaminator and Smartphone Geiger Counter

In July 2011, the S.T. Corp. Introduced 105-gram radiation dosimeters for home use that cost about $190. In September 2011, Docomo introduced the prototype for a smartphone cover capable of measuring radiation levels. In October 2011 researchers from the Wakasa Wan Energy Research Center in Fukui Prefecture, central Japan said it had developed a handheld device capable of removing radioactive substances using laser beams. The device uses laser beams moving at a high speed to scrape off radioactive substances attached to the surface of pipes and other objects at nuclear power plants. The dust is then collected inside the machine.The researchers say that, since only the surface is scraped off, the machine generates one thousand times less radioactive waste than conventional methods. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com October 28, 2011]

The device is about 30 centimeters high and wide, and 40 centimeters long. The team says it is the world's first portable radiation decontaminator. When the researchers began developing the machine 7 years ago, they meant it to be used to reduce radioactive waste from nuclear plants, and also in the decommissioning of a prototype test reactor in Fukui Prefecture.

vehicle decontamination Sanwa Corp., a manufacturer in Otamamura, Fukushima Prefecture, has developed a geiger counter that allows users to display radiation readings on a smartphone. Selling for about $120, the device is 14 centimeters long, three centimeters wide and 2.5 centimeters thick. Users who connect it to their smartphone also can create maps of radiation levels on the phone's screen. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 16, 2011]

"I wanted to develop measuring devices for parents who are concerned about their children's health [due to possible radiation exposure]," said company President Yuichiro Saito, 43. He and his 11 employees have worked on the product since June, as part of an Internet project in which participants shared knowledge to develop measuring devices. Sanwa also plans to release another geiger counter with a liquid crystal display at 18,800 yen per unit. The company has already received about 3,000 reservations for the two products. (Nov. 16, 2011)

After the Japanese government lifted an evacuation advisory for parts of Tamura City and 4 other municipalities outside the 20-kilometer no-entry zone around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in September 2011, Tamura City began monitoring radiation levels of farmlands and forests with a small unmanned helicopter. The Japan Atomic Energy Agency, which began monitoring radiation using the drone at the request of the city, first tested a 300-meter-long, 150-meter-wide area of a rice field from a helicopter equipped with a measuring instrument about 20 meters above the ground. It also carried out tests on forests. Data transmitted by the helicopter is reportedly translated into radiation levels 1 meter above the ground and indicated by instruments at ground level. Aircraft are suitable for measuring radiation levels of large areas and other locations that are difficult for people to access. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com November 5, 2011]

High Levels of Radioactive Cesium Found in Tokyo

Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times, “Takeo Hayashida signed on with a citizens’ group to test for radiation near his son’s baseball field in Tokyo after government officials told him they had no plans to check for fallout from the devastated Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Like Japan’s central government, local officials said there was nothing to fear in the capital, 160 miles from the disaster zone. Then came the test result: the level of radioactive cesium in a patch of dirt just yards from where his 11-year-old son, Koshiro, played baseball was equal to those in some contaminated areas around Chernobyl. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times October 14, 2011]

The patch of ground was one of more than 20 spots in and around the nation’s capital that the citizens’ group, and the respected nuclear research center they worked with, found were contaminated with potentially harmful levels of radioactive cesium. It has been clear since the early days of the nuclear accident that that the vagaries of wind and rain had scattered worrisome amounts of radioactive materials in unexpected patterns far outside the evacuation zone 12 miles around the stricken plant. But reports that substantial amounts of cesium had accumulated as far away as Tokyo have raised new concerns about how far the contamination had spread, possibly settling in areas where the government has not even considered looking.

A radioactivity level higher than that of areas near the crippled Fukushima nuclear power plant has been detected at a Tokyo elementary school. A level of 3-point-99 microsieverts per hour was observed 5 centimeters above ground just beneath a rainwater pipe at the school in Tokyo's Adachi Ward. Radiation levels in Fukushima City about 60 kilometers from the plant were around 1 microsievert per hour. The ward is about 210 kilometers from the plant. Ward authorities plan to remove soil and trees from the school area and measure radiation in ditches at about 800 locations including schools, parks and other public facilities. The school's principal says he was stunned to hear about the radiation and cancelled physical education classes and other activities in the schoolyard for the day. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com October 14, 2011]

Tokyo Residents Do Their Own Radiation Testing

Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times, “Tokyo residents knew soon after the March 11 accident that they were being exposed to radioactive materials. Researchers detected a spike in radiation levels on March 15. Then as rain drizzled down on the evening of March 21, radioactive material again fell on the city. In the following week, however, radioactivity in the air and water dropped rapidly. But not everyone was convinced. Some Tokyo residents bought dosimeters. The Tokyo citizens’ group, the Radiation Defense Project, which grew out of a Facebook discussion page, decided to be more proactive. In consultation with the Yokohama-based Isotope Research Institute, members collected soil samples from near their own homes and submitted them for testing. [Source: japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times October 14, 2011]

Some of the results were shocking: the sample that Mr. Hayashida collected under shrubs near his neighborhood baseball field in the Edogawa ward measured nearly 138,000 becquerels per square meter of radioactive cesium 137, which can damage cells and lead to an increased risk of cancer. Of the 132 areas tested, 22 were above 37,000 becquerels per square meter, the level at which zones were considered contaminated at Chernobyl.

Edwin Lyman, a physicist at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, said most residents near Chernobyl were undoubtedly much worse off, surrounded by widespread contamination rather than isolated hot spots. But he said the 37,000 figure remained a good reference point for mandatory cleanup because regular exposure to such contamination could result in a dosage of more than one millisievert per year, the maximum recommended for the public by the International Commission on Radiological Protection.

The most contaminated spot in the Radiation Defense survey, near a church, was well above the level of the 1.5 million becquerels per square meter that required mandatory resettlement at Chernobyl. The level is so much higher than other results in the study that it raises the possibility of testing error, but micro hot spots are not unheard of after nuclear disasters.

Japan’s relatively tame mainstream media, which is more likely to report on government pronouncements than grass-roots movements, mainly ignored the citizens’ group’s findings. “Everybody just wants to believe that this is Fukushima’s problem,” said Kota Kinoshita, one of the group’s leaders and a former television journalist. “But if the government is not serious about finding out, how can we trust them?”

Hideo Yamazaki, an expert in environmental analysis at Kinki University in western Japan, did his own survey of the city and said he, too, discovered high levels in the area where the baseball field is located. “These results are highly localized, so there is no cause for panic,” he said. “Still, there are steps the government could be taking, like decontaminating the highest spots.”

Since then, there have been other suggestions that hot spots were more widespread than originally imagined. In September, a local government in a Tokyo ward found a pile of composted leaves at a school that measured 849 becquerels per kilogram of cesium 137, over two times Japan’s legally permissible level for compost. A few weeks later civilians who tested the roof of an apartment building in the nearby city of Yokohama — farther from Fukushima than Tokyo — found high quantities of radioactive strontium.

The government’s own aerial testing showed that although almost all of Tokyo had relatively little contamination, two areas showed elevated readings. One was in a mountainous area at the western edge of the Tokyo metropolitan region, and the other was over three wards of the city — including the one where the baseball field is situated. The metropolitan government said it had started preparations to begin monitoring food products from the nearby mountains, but acknowledged that food had been shipped from that area for months. Mr. Hayashida, who discovered the high level at the baseball field, said that he was not waiting any longer for government assurances. He moved his family to Okayama, about 370 miles to the southwest. “Perhaps we could have stayed in Tokyo with no problems,” he said. “But I choose a future with no radiation fears.”

Radiation "Measurement Movement”

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: When it comes to radiation, residents have decided to take matters into their own hands. In what has become known as the "measurement movement," young families in this nation long known for safety and hygiene have acquired their own Geiger counters and dosimeters to gauge radiation exposure. Many of the devices can be purchased at DVD rental stories, where they are stocked next to the latest blockbuster movies. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, December 18, 2011]

As the central government has relaxed radiation limits for food, nuclear workers and even school playgrounds, residents have established community groups to take collective action to ensure that the levels remain safe. The Radiation Defense Project, for instance, which grew out of a Facebook discussion page, has taken steps such as collecting money to take soil samples on school grounds in Tokyo and elsewhere and have them analyzed at private testing facilities.

Even after the Tokyo city government tried to reassure residents, announcing that it would conduct radiation tests on samples of store-bought food, consumers remain doubtful. Some independent groups have established free, on-the-spot analysis of radioactive isotopes in food products at stores in Fukushima prefecture, where the nuclear meltdown took place.

Health Consequences of Fukushima Radiation Releases

radiation inside Unit 1 Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: Government scientists estimate that the total radiation released on land was about a sixth of the level at Chernobyl. Unlike the Russians, Japanese authorities warned parents not to give local milk to their children. An analysis published by the Princeton University physicist Frank von Hippel estimated that roughly a thousand deadly cancers may result from the Fukushima meltdowns; he cautioned that the data are preliminary and that psychological effects should be considered as well. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 17, 2011]

Dr. Fred A. Mettler, Jr., the American representative to a United Nations committee on radiation assessment, said, “Forty per cent of people in developed countries get cancer anyway, so, compared to that normal rate, I think the risk is going to be low — and may not be detectable.” Of nearly four thousand workers who have passed through the plant since the meltdowns, only a hundred and three have been found to have received more than a hundred millisieverts of radiation. At that level, scientists predict about a one-per-cent increase over the normal rate of cancer. The most serious cases are two workers who were exposed to more than five hundred millisieverts in the first weeks of the crisis.

Discover health journalist Jeff Wheelwright says the evidence linking small radiation doses to cancer is flimsy. He wrote: “Radiation can be precisely measured in the environment, but the biological effects at low levels can only be guessed at. That there will be some human cancers is assumed, thanks to the linear no-threshold theory of cancer, which holds that no radiation dose is so small that it cannot produce a probability of cancer. This theory was proposed after World War II, when researchers found that survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had disproportionately high rates of cancer later in life. Scientists used those data to extrapolate how many excess cancer cases would develop at lower radiation doses. Today these incremental cases are believed to exist even though there is no way to detect them against the normal background of disease: Even without man-made radiation exposure, about one in three people develop cancer. [Source: Jeff Wheelwright, Discover, July 5, 2012]

“Fukushima evacuees will be allowed to return home once cleanup efforts bring exposure down to 20 millisieverts per year, equivalent to two or three abdominal CAT scans. The no-threshold theory predicts that if everyone returns and absorbs that dose during their first year back, 80 extra people (1 in 1,000) will eventually develop cancer. “They take the very tiny radiation and multiply it by a large population,” says John Boice Jr., director of the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. “It causes undue alarm. Those cancers can’t be measured. They may not be there at all.”

How Much is 20 Millisieverts? 1) Six times the yearly dose absorbed in the course of everyday life; 2) two to three times the radiation from one abdominal CAT scan; 3) one fifth the lowest does known to increase cancer risk.

See Separate Article RADIATION AND PROBLEMS WITH NUCLEAR ENERGY factsanddetails.com

Iodine 131, Cesium 137 Worries About Radiation from the Fukushima Plants

Radioactive material is a term that comprises unstable elements that discharge radioactivity and heat in nuclear fission. There are many kinds of such material found in nature. Uranium and plutonium are two kinds that are used as fuel in nuclear power generation. The level of risk they pose to humans varies. If radioactivity harms the genes in human cells or other organs, the risk of cancer and leukemia increases. In a worst case scenario, people may suffer from acute radiation poisoning.

In a nuclear accident, radioactive isotopes including iodine-131 and cesium-137, which are normally contained inside the fuel rods, may be released into the atmosphere as gases or particulates if the rods are damaged. These can be inhaled or ingested through contaminated food or water. Children are especially susceptible to radiation poisoning from iodine, which can accumulate in the thyroid gland, according to the World Health Organization.

The radiation initially released by the explosions at leaks at the Fukushima nuclear power plant was mostly isotope iodine 131, which is not that dangerous in the long term because it decays relatively quickly. Iodine 131 has a half life of only eight days and disappears completely from the environment within a couple months. Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times, “Iodine 131 is dangerous because it concentrates in the thyroid gland, resulting in high radiation doses to that vulnerable organ. The thyroid is such an iodine magnet that a week after a nuclear weapons test in China, iodine 131 could be detected in the thyroid glands of deer in Colorado, although it could not be detected in the air or in nearby vegetation.”

More serious worries were raised when a long-lasting radioactive element, cesium 137 were measured at levels that pose a long-term danger at one spot 25 miles from the Fukushima plant. The amount of cesium 137, measured in one village 25 miles from the plant by the International Atomic Energy Agency exceeded the standard that the Soviet Union used as a gauge to recommend abandoning land surrounding the Chernobyl reactor. Using a measure of radioactivity called the becquerel, the tests found as much as 3.7 million becquerels per square meter; the standard used at Chernobyl was 1.48 million. This lead to concerns that a large chunk of land might to have to be abandoned for years. Cesium-137 has a relatively long half life of about 30 years and can accumulate in the muscles once it is in the body and can cause cancer.

The New York Times reported: “In contrast to iodine 131, which decays rapidly, cesium 137 persists in the environment for centuries. The reported measurements would not be high enough to cause acute radiation illness but far exceed standards for the general public designed to cut the risks of cancer. The Japanese authorities and the anti-nuclear environmental group Greenpeace have reported similar readings from the area; Greenpeace and some other groups are pressing for the affected area to be evacuated.” More than 15 years after the Chernobyl accident in what is now Ukraine, studies found that cesium 137 was still detectable in wild boar in Croatia and reindeer in Norway, with the levels high enough in some areas to pose a potential danger to people who consume a great deal of the meat.

Cesium-137 that enters the body is distributed throughout the soft tissues, especially in muscle. Cesium-137 is eliminated faster from the body than other radionuclides, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Slowly, but surely it will pass out of the body,” Stephen Lincoln, a professor of chemistry at the University of Adelaide in South Australia, told Bloomberg. [Source: Kanoko Matsuyama and Yuriy Humber, Bloomberg, December 7, 2011]

One of the critical factors determining the extent of the danger posed by radiation releases has been wind direction. Most of the time the prevailing westerlies carried the radiation out to sea, where it didn’t pose much of a threat to human life and largely dispersed before it reached inhabited areas in the Americas. Most worrisome for Japan were northerly winds that pushed the radiation south towards Tokyo and other densely populated areas of Japan.

Thyroid Cancer, Children and the Fukushima Accident

In October 2011, the Fukushima prefectural government began thyroid examinations for children in an effort to assess the health impact of the nuclear accident. The examinations will cover around 360,000 youths aged 18 or younger, Their health will be monitored for their lifetime. Radioactive iodine released from the damaged nuclear plant could accumulate in children's thyroid glands, raising the possibility of cancer.

On the first day of testing 150 children from some municipalities in the government-designated evacuation zone, such as Iitate Village and the Yamakiya district of Kawamata town, underwent ultrasound examinations for tumors or other problems at Fukushima Medical University. The results are expected to be mailed to them in about a month. Specific test results will not be made public. The prefectural government says it plans to have all the children examined by 2014. After that, it says the children will undergo a thyroid check every 2 years until they turn 20, and will be examined once every 5 years after that age.

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “In the case of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, Prof. Shinichi Suzuki of Fukushima Medical University believes there is "a low probability" that local children will develop thyroid cancer. He cites restrictions being issued on drinking locally produced milk and tap water soon after they were found to have been contaminated with radioactive material beyond regulated standards as one factor supporting his views.

Suzuki's opinion is shared by Minoru Kamata, director emeritus at Suwa Central Hospital in Chino, Nagano Prefecture, who offered medical assistance in 1991 in areas hit by the Chernobyl accident. "However, those children who were outdoors just after the nuclear accident [at the Fukushima plant] will need to be checked for possible adverse reactions," he said.

Tatsuhiko Kodama, head of the University of Tokyo's Radioisotope Center, said it took 20 years for experts to prove that the Chernobyl accident caused the increase in thyroid cancer incidents among the local children. "Epidemiological studies alone take time [to prove a link between a disease and its cause]," he said. "And when we are able to confirm this link, it's usually too late to take countermeasures. "If more and more people in Fukushima Prefecture develop other types of cancers [apart from thyroid], we need to think of other measures, such as providing medical checkups to investigate possible damage to genes," Kodama said.

Thyroids of Fukushima Children Same As Other Children But High Internal Radiation Exposure Found in Some Kids

Jiji Press reported: “Thyroid lumps detected in children in Fukushima Prefecture, home to the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, appear at almost the same rate as in children from three other prefectures, according to the Environment Ministry. In the survey, a total of 4,365 people aged between 3 and 18 in the three prefectures of Aomori, Yamanashi and Nagasaki underwent the same ultrasound examination being performed on children in Fukushima. The survey, conducted from November last year, found that 2,469 of them, or 56.6 percent, have lumps measuring 5 millimeters or smaller, or cysts of 20 millimeters or smaller in their thyroid glands in a status known as A2, the ministry said in a preliminary report Friday. Forty-four, or 1 percent, are in status B, having larger lumps or cysts that require further examination, the report said. No lumps or cysts were found in the remaining 1,852 children, it added. [Source: Jiji Press, March 10, 2013 ^^]

“The survey examined children in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture; Kofu, Yamanashi Prefecture; and Nagasaki. Meanwhile, ultrasounds are being conducted by the Fukushima prefectural government on residents in the prefecture from newborns to those who were 18 years old at the outbreak of the crisis at Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima plant. The results of the tests were available for about 130,000 people as of January, with the proportion of those classified as A2 and B coming to 41.2 percent and 0.6 percent, respectively. The ministry believes the figures were lower in Fukushima than in the other prefectures because the data in Fukushima covered children from newborns to the age of 2. The Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant has released a massive amount of radioactive substances, including iodine, after being damaged in the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami in March 2011. Radioactive iodine tends to accumulate in the thyroid gland. ^^

In October 2011, Kyodo reported: Two boys in Fukushima Prefecture have been internally exposed to the highest levels of radiation among the nearly 4,500 residents who were checked amid the nuclear crisis. The level of exposure is estimated to be equivalent to 3 millisieverts during their lifetime, which is not expected to harm their health, prefectural officials said. The local government has not disclosed the boys' exact ages, saying only that they are between 4 and 7 years old. [Source: Kyodo, japan-afterthebigearthquake.blogspot.com October 22, 2011]

Both boys are from the town of Futaba, which partly hosts the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant. The two had the highest levels of internal exposure among 4,463 residents tested between June 27 and September 30 in 13 high-risk municipalities, the officials said. Among others tested, eight people measured 2 millisieverts, six registered 1 millisievert and the remaining 4,447 residents had less than 1 millisievert, they said.

They were tested with whole body counters at either the National Institute of Radiological Sciences in the city of Chiba or at the Japan Atomic Energy Agency in Tokai, Ibaraki Prefecture. Estimates for adults were calculated to measure accumulated radiation exposure in the coming 50 years, and for children until they reach the age of 70.

In November 2011, a medical consulting firm in Tokyo says radioactive material has been detected in the urine of 104 children in Fukushima Prefecture, the site of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. RHC JAPAN collected urine from children aged 6 or younger in Minamisoma City to check for possible internal exposure. Those checks were done at the request of parents of preschool children. Tests being carried out by local governments only cover elementary school students and older. Of 1,500 samples that have been analyzed so far, 7 percent contain radioactive cesium.

The levels of material detected were mostly between 20 and 30 becquerels per liter, slightly above the detection limit. The highest was 187 becquerels in the sample of a one-year-old boy. The firm says there has been no internal exposure that could affect human health. National Institute of Radiological Sciences Director Makoto Akashi says that although those test results need verification, they do point to the possibility of internal exposure in Fukushima children. He added that the level of internal exposure would not increase if one eats food tested for radioactivity.

Japanese Governement Raises Radiation Limits

John M. Glionna and Kenji Hall wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The parents were furious: Why, they demanded, had Japanese officials raised the acceptable level of radiation exposure for schoolchildren near the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant? By upping the limit, children were allowed on playgrounds containing higher levels of radioactivity than had been permitted before the nearby atomic plant was damaged by the devastating March 11 earthquake and tsunami, the parents said. Although it may be impossible to rid the air of dangerous isotopes, they said, the ground is a different matter. [Source: John M. Glionna and Kenji Hall, Los Angeles Times, June 14, 2011]

“At a government-convened meeting here parents demanded that authorities reinstate stricter radioactivity standards and begin stripping the top layer of soil off contaminated playgrounds. But officials stood their ground. And in a nation where polite public discourse is the norm, the dialogue quickly turned hostile. A woman in the front row cut off one spokesman: "In the playground, in the sandbox, children put dirt into their mouths! They breathe in the dust! You should do the same! Lick the dirt!" she shouted to applause. “You wouldn't do this to your own kids!?"

“Under the new guidelines, the government set the upper limit of safe radiation exposure for children at 20 millisieverts per year, from 1 millisievert previously. Later, Japan's Education Ministry pulled an about-face, announcing plans to return exposure limits for children at school to 1 millisievert a year. Officials said they would also cover the cost of removing the surface soil from schoolyards where the limit is exceeded.” "We have taken the measure so children and their parents can feel relieved," Education Minister Yoshiaki Takaki said at a news conference.

“Scientists say a cumulative dose of 500 millisieverts of radiation increases the risk of cancer and that children in the region of the plant consequently face a particularly high risk over the course of their lifetimes. The government's initial raising of the exposure limit for schoolchildren prompted one key nuclear adviser to quit in protest.” At times fighting back tears, Toshio Kosako, a professor at the University of Tokyo and an expert on radiation exposure, told reporters in late April that he was against what he considered inappropriate radiation limits.

"I cannot allow this as a scholar," said Kosako, who was appointed by Prime Minister Naoto Kan. "I feel the government response has been merely to bide time."

Iodine releases

“As the debate raged, some cities took matters into their own hands. In Koriyama city, 40 miles west of the stricken nuclear plant, officials found high radiation levels on playgrounds at many schools. They hired bulldozers to scrape the top layer of soil from playgrounds at 67 day care centers, elementary schools and junior high schools. The move lowered radiation levels by 40 percent to 90 percent, according to results posted on the city's website. "We decided not to wait for guidance from the central government," said Hiroshi Nozaki, a Koriyama board of education official.”

On May 23, hundreds of demonstrators braved a steady drizzle in Tokyo to protest the government's policy, holding signs that said "The government kills people" and "Adults are responsible." Afterward, in a hallway at a government ministry where the protesters gathered, Saori Kanzawa tended to her daughter Riko, a 4-year-old with pins holding her bangs and Little Mermaid socks. The family had fled Koriyama for Tokyo, worried about radiation from the damaged plant. "Had we stayed at home, we would have had to tell Riko that she can't go to this park or play on that slide," said Kanzawa, 32. "It's impossible to know how the radiation would affect Riko in the next five to 10 years or longer. She may want to have children in the future, and as parents we have to do everything we can to limit her risk of radiation exposure."

Image Sources: TEPCO and Greenpeace Japan

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, Daily Yomiuri, Japan Times, Mainichi Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2020