IWATE PREFECTURE

Tsunami Damage Iwate Prefecture, located in the northeast part of Japan, covers 15,278.4 square kilometers (5,900 square miles), is home to about 1.3 million people and has a population density of 83.8 people per square kilometer. It is in Tohoku on northern Honshu island and has 10 districts and 33 municipalities. The coast of Iwate and towns and fishing settlements there were badly damaged by the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami

Iwate is the second largest prefecture after Hokkaido. It is full of charm throughout the four seasons and boasts stunning views of the sea from the rias coastline, elegant mountains, and many historical sites. A rias coastline is made up of long, narrow inlets formed by the partial submergence of a river valleyes. Goshono Jomon Park (Ichinohe) contains the ruins of Jomon period settlements dating back to about 4,000 years ago. Morioka Castle Site Park in Morioka is famous for its cherry blossoms in the spring and fall colors in the autumn. “Hiraizumi-Temples, Gardens, and Archaeological Sites Representing the Buddhist Pure Land” in Hiraizumi was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. See Sendai articles factsanddetails.com

Morioka

Morioka (accessible by the shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo) is the capital and largest city in Iwate Prefecture , with about 300,000 people. Located inland at the confluence of three rivers — the Kitakami, the Shizukuishi and the Nakatsu — almost equidistant fromm the Pacific Ocean and Sea of Joan, it was in an area inhabited by the Emishi people into the Heian period. During the Enryaku era Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, was ordered north to Shiwa Castle in 803 to establish s a military center to extend the domination of the Yamato dynasty over Mutsu Province.

Sights in the city include the The Iwate Museum of Art the Rock-Breaking Cherry Tree (designated a natural monument of Japan), the Iwate Prefectural Museum, Morioka Castle, the Shiwa Castle ruins and Bank of Iwate Red Brick Building. Getting There: It takes about 2 hours and 10 minutes from Tokyo to Morioka Station on the Tohoku Shinkansen line.

Iwate Museum of Art opened in 2001 in Morioka City’s Chuo Park. It holds a large collection of works by artists from the region, namely Tetsugoro Yorozu, Shunsuke Matsumoto, and Yasutake Funakoshi; all important figures in shaping Japanese modern art. The museum also organizes exhibitions with contemporary artists, as well as young artists from Iwate. Nearby in Chuo Park are the Study Museum of Archeological Site, the Children’s Science Museum, and the Morioka Memorial Museum of Great Predecessors, all worth visiting.

Places in Iwate Prefecture

Esashi-Fujiwara Heritage Park (Oshu City) is where “Homura Tatsu,” a long-running TV series on the Heian Era’s rise and fall of the Oshu-Fujiwara clan, was shot.Around 120 buildings from 794 to 1192 have been reproduced on a site of about 20 hectares. The entrance fee in ¥1,200. Esashi in the land where the first generation of the Oshu-Fujiwara clan, Lord Kiyohira, and his father, Lord Tsunekiyo, lived. Lord Kiyohira is the person who erected the “KONJIKIDO” in Hiraizumi, a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site. “Esashi-Fujiwara Heritage Park” was built in 1993.The reconstruction of buildings and streets of the Heian period has been used for the filming of other TV shows.

Hachimantai Hills is a pleasant place for hiking and enjoying nature. The Hachimantai region, part of the Towada-Hachimantai National Park, features alpine meadows and forest trails. In winter, don’t miss the soaring snow walls, superb skiing or a soak in the region’s famed hot springs. Hachimantai Mountain Hotel https://hachimantai-mountainhotel.com/en/

Tono (50 kilometers northwest of Hiraizumi) is known best for its association with old folk tales and supernatural beings. Attractions include a folk village, a temple with a lion people rube for good luck and a traditional farmhouses with quarters with people and horses.

Disaster Tour of the Miyako Coast

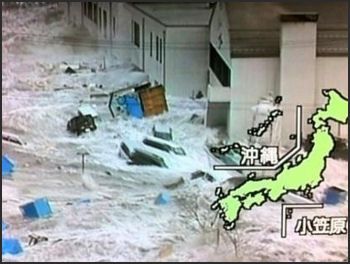

Tsunami on Japanese television

The Miyako Coast of Iwate is a beautiful area that extends for some distance along the Pacific Ocean but devastated by the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Yuka Matsumoto wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The sea of oddly shaped rocks begins to gleam in the sunlight, though visitors still feel a chill in the wind in Miyako, Iwate Prefecture. There’s a saying that “once cherry trees blossom, yamase begins to blow” in this city along the Rikuchu coast. Yamase is a cold seasonal wind. The Manabu Bosai (disaster management study) guided tour has turned a new page after beginning in the Taro district in 2012, the year after the Great East Japan Earthquake. It started as an emergency project by the prefectural government, but the Miyako city government decided to continue it and has entrusted the Miyako Tourism Cultural Exchange Association with the project since fiscal 2017. [Source: Yuka Matsumoto, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 17, 2017]

“Tsunami easily topped a 10-meter-high coastal levee, dubbed the Great Wall, during the disaster. The land was raised in the city and a new coastal levee is being constructed, making it hard to imagine the original view of Taro. Kumiko Motoda, a guide for the Manabu Bosai tour, explains about the coastal levee in the Taro district. “That’s why we want people to learn along with us,” said tour guide Kumiko Motoda, 59. On the tour, participants visit the damaged coastal levee and Taro Kanko Hotel, which the city government has preserved as tsunami memorials.

“Taro was known as the “disaster management town,” having prepared for disasters since it was hit by massive tsunami in the Meiji (1868-1912) and Showa (1926-89) eras. However, the latest tsunami claimed many lives. There have been over 120,000 participants in the tour, which describes the pain felt and lessons learned. The Sanriku region used to be at the bottom of the sea, and its beautiful indented coastline is the result of repeated upheaval and encroachment. Jodogahama beach, which is said to be “the land of perfect bliss,” showed its seabed on the day of the 2011 disaster. Local people say they saw the seabed, more than 10 meters below the land, following the backwash. “I’d never been so scared,” said Jun Shimazaki, who works for the Jodogahama rest house facing the sea, recalling the disaster. The 37-year-old said he didn’t hear even a single Japanese gull crying at that time. Although the guests and employees of the hotel evacuated to safety, the building — which had just been remodeled — was destroyed. With the help of volunteers, Shimazaki cleaned the beach where debris had washed up and the rest house resumed business a year later.

“The beach saw more tourists in the two or three years after the 2011 earthquake, thanks partly to the NHK serial drama “Amachan,” but Shimazaki believes business “will be put to the test from now on.” Atsuhiko Seki, general manager of the Park Hotel Jodogahama, thinks along the lines of Shimazaki. “Making it resemble the original is not enough,” said Seki. “We must go forward.” Overlooking the beach, the Park Hotel Jodogahama was not damaged during the disaster and was temporarily used as a shelter. The hotel underwent a full renovation last year, and the space for its restaurant was expanded so diners can relax while gazing at the sea. The hotel also introduced a kitchen where local foods are cooked up before customer’s eyes.

“A number of efforts were made after the disaster. For example, the Kyukamura Rikuchu Miyako hotel, located on a hill, constructed a camping area in the Anegasaki district equipped with a solar power system and chip boiler to be used in the event of a disaster. Another company started an eco-car sharing business to lend electric vehicles that serve as power sources in case of emergency.

”Wanting to see up close the natural beauty of the jagged coastline, I rode in a small boat called the “sappabune,” traveling through a gap in the rocks toward the mysterious Blue Cave. If you want to see the uniquely shaped rocks along the bay in more depth, the Miyako Jodogahama Boat Cruise is a fantastic choice. You can truly appreciate Rosokuiwa (candle rock), Hideshima (rising-sun island) and Shiofukiana (spouting blowhole), among other sights.

”Aoi Yokoyama, 20, served as our guide on the boat, which was saved from the tsunami by its skipper. Yokoyama said she’d planned to study outside the prefecture but volunteered for her current position after watching guides work very hard, undaunted by the disaster. She said she wants to enliven the area through tourism. The Sanriku is certified as one of the Japan Geoparks, serving as an outdoor museum to help showcase the workings of the Earth.During the Manabu Bosai tour, I was speechless as I watched video footage showing the dark tsunami topping the coastal levee in the Taro district. Getting There: It takes about 2 hours and 10 minutes from Tokyo to Morioka Station on the Tohoku Shinkansen line. From there, it takes 2 hours and 15 minutes to reach Miyako Station by bus. It is 15 minutes from the station to Jodogahama beach by bus or car. For more information, call the Miyako Tourism Cultural Exchange Association at (0193) 62-3534.

Sanriku Fukko (Reconstruction) National Park

Sanriku Fukko National Park (in Aomori, Iwate and Miyagi prefectures) integrates parks damaged by March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Opened it 2013, the park comprises Rikuchu Kaigan National Park, which straddles Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, and Tanesashi Kaigan Hashikamidake Prefectural Natural Park, which straddles Hachinohe and Hashikami in Aomori Prefecture. The Environment Ministry said it launched the park to draw tourists to the shores of the Sanriku region and help support reconstruction of the disaster-hit areas. Sanriku Fukko means Reconstruction. [Source: JapanNews, May 28, 2013]

The Japan News reported: “The new national park includes 14,635 hectares on land and 41,300 hectares offshore. The city government of Miyako, Iwate Prefecture, will preserve a camp facility that was damaged in the disaster as a memorial site dedicated to education on the threat of tsunami. The city government also plans to integrate nearby parks into the site. The Tanesashi Kaigan coast, which forms part of the new national park, boasts a microthermal climate in which cool winds called yamase blow in the summertime.

“In the coastal areas, at least about 670 species of vegetation, including alpine plants, grow. Meisho Tanesashi Kaigan, Samemachi no Shizen o Mamoru Kai is a local residents association dedicated to preserving the coastal scenery and the Samemachi district of the city. The group was established 15 years ago. Currently, the association’s 100 members regularly patrol the areas to prevent precious plants from being stolen. Mariko Fukuda, 63, the head of the association, said: “Flowers here endure salty wind and severely cold weather in winter, and still they blossom. I hope the area’s designation [as a new national park] will encourage many people to visit to see the flowers.”

“According to Fukuda, the disaster greatly affected plants along the Tanesashi Kaigan coast. Pine forests were engulfed in sand carried by the tsunami and plants from the benibana-ichiyakuso flower species disappeared. Fukuda said she was also surprised to see many patches of unran, a variety of toadflax, blossoming in pine forests, as previously the plant was only found on sandy beaches. She was struck by the toughness of nature, she said.

“Some local people voiced concern that an increase in tourists could lead to the theft of valuable plants or plants on the sides of trails being trampled. But Fukuda replied: “Because [the visitors would likely] want to view the flowers, I don’t believe they would do such harmful things. We want to pass on the importance of the wonderful nature on the Tanesashi Kaigan coast to later generations through the flowers.” Shigeru Chiyokawa, 59, is a representative manager of Sanriku Hana Hotel Hamagiku, which was flooded by tsunami. He aims to reopen the hotel in Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, in late August. “It’s meaningful that the name of the park contains the word fukko. We want to contribute to reconstruction through promoting tourism,” he said.

“The hotel inside Rikuchu Kaigan National Park was named Namiita Kanko Hotel before the disaster, but will change its name before reopening. A sandy beach in front of the hotel has shrunk due to ground subsidence, but Chiyokawa said: “The natural environment will return to its previous state some day in the future. I want to tell our guests how strong nature is.” Kesennuma is the only municipality in Miyagi Prefecture that is inside Rikuchu Kaigan National Park.”

Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of March 11, 2011

On March 11, 2011, an earthquake struck off the coast of Japan, producing a devastating tsunami that sent walls of water washing over coastal towns, cities and farmland in the northern part of the country and set off warnings as far away the west coast of the United States and South America. Recorded as 9.0 on the Richter scale, it was the most powerful quake ever to hit Japan and the seventh strongest ever recorded globally (tied for forth since 1900). It was also Japan's worst natural disaster since World War II (earlier earthquakes and tsunamis killed more people).

In Japan it became known as the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami or the Tohoku Pacific Offshore Earthquake (Japanese refer to northern Honshu, especially the northeast side of the island as Tohoku). The coastal areas of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures suffered particularly severe damage, due to devastating tsunami more than 10 meters high. Joshua Hammer wrote in the New York Times, “The devastation stretched along hundreds of miles of seacoast; towns washed away by mudslides; trains carried out to sea; thousands of survivors left stranded on roofs, awaiting rescue. The quake also led to... the partial meltdown of at least two nuclear reactors. Only the fact that the epicenter was not near a densely populated area prevented far greater casualties.”

The 9.0- magnitude earthquake was so powerful it shifted the position of the Earth’s figure axis by as much as 15 centimeters and moved Honshu, Japan’s main island, two and half meters eastward. The tsunami generated by the earthquake obliterated towns and damaged hundreds of thousands of buildings, including four reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The cost of disasters worldwide was the highest ever in 2011 ($380 billion), mainly due the earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

The total number of casualties confirmed by Japanese National Police Agency in March 2019 was 18,297 dead, 2,533 missing and 6,157 injured. A total of 196,559 buildings were destroyed or damaged. More than 460,000 were made homeless and sought refuge in shelters. This included 150,000 in Miyagi Prefecture, 47,000 in Iwate Prefecture and 130,000 in Fukushima Prefecture. In the first three days after the disaster Japan’s Self Defense Forces (the Japanese military) rescued 66,000 people, many of them stranded on hilltops and rooftops and among debris. Because reaching them by land was so difficult many had to wait to be retrieved by helicopter, which could carry only a few people at a time. Thousands of others evacuated their homes due to the crisis at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

A large number of victims were from Miyagi Prefecture. Ishinomaki was one of the worst-hit cities. When the death toll topped 10,000 on March 25: 6,097 of the dead were in Miyagi Prefecture, where Sendai is located; 3,056 were in Iwate Prefecture and 855 were in Fukushima Prefecture and 20 and 17 were in Ibaraki and Chiba Prefectures respectively. At that point 2,853 victims had been identified. Of these 23.2 percent were 80 or older; 22.9 percent were in their 70s; 19 percent were in their 60s; 11.6 percent were in their 50s; 6.9 percent were in their 40s; 6 percent were in their 30s; 3.2 percent were in the 20s; 3.2 percent were in their 10s; and 4.1 percent were in 0 to 9.

Links to Articles in this Website About the 2011 Tsunami and Earthquake: 2011 EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI: DEATH TOLL, GEOLOGY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ACCOUNTS OF THE 2011 EARTHQUAKE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DAMAGE FROM 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TSUNAMI WIPES OUT MINAMISANRIKU Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SURVIVORS OF THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DEAD AND MISSING FROM THE 2011 TSUNAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CRISIS AT THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Damage Soon After the Tsunami

Koji Yasuda of the Yomiuri Shimbun Staff flew in plane over the devastated area the day after the earthquake and tsunami. After taking of from Hokkaido he reported: “The plane flew further south. The town of Kuji, Iwate Prefecture, once nestled in the curve of a bay, had been swept away by a tsunami. The ground was soaked in seawater and shining as it reflected the sunlight. [Source: Koji Yasuda, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 13, 2011]

A settlement, above which white smoke was rising, was spotted at the back of another bay. It was Yamadamachi in Iwate Prefecture. The town was swallowed up by sea waters. After a series of tsunami waves Friday, the seawater surface was already calm. But pieces of wreckage were floating around the area. At 8:53 a.m., the plane flew over Ofunato, Iwate Prefecture. The flatland, which extends into the sea like a cape, was totally swallowed by a tsunami, leaving no trace that a town was there. On an area of higher ground, I spotted a dozen cars and several people. I wondered if they were waiting to be rescued. They were looking up the sky with dazed expressions.” [

“The next town south was Rikuzen-Takata, but almost no buildings were to be seen where the town should have been located. It seemed as if the port town had suddenly vanished. What I could see there were only medium-rise buildings believed to be made of reinforced concrete, such as a hospital. Piles of rubble were seen scattered even as far as wooded areas several kilometers away from the coastline.”

Kamaishi, and the Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011

Kamaishi

Kamaishi (150 kilometers north-northeast of Sendai) is a steel and fishing town of around 40,000 that was devastated by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Norimitsu Onishi wrote in the New York Times: The tsunami “killed about 1,300 people in Kamaishi, whose low-lying areas have been transformed into a dusty ghost town where the smell of ruined buildings now mingles with that of the sea. The birthplace of Japan’s steel industry, Kamaishi played a key role in the country’s modernization and militarization, so that it became the first target on mainland Japan of American warships during World War II. During Japan’s postwar boom, the city’s population swelled as it easily overcame the ravages of two tsunamis.” [Source: Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times, April 4, 2011]

“Kamaishi became famous for its delicious seafood; the winning ways of the rugby team of its main employer, Nippon Steel; and its diversions. As Japan’s fortunes have declined in the past two decades, Kamaishi’s fall has been faster and steeper. Its population, nearly 100,000 two generations ago, has now fallen below 40,000 and is aging. Many who have lost homes and businesses here are not expected to remain.”

“Kamaishi’s economy peaked a decade before Japan’s did, as the city’s two main industries began declining in the 1970s. Nippon Steel began moving its operations out of Kamaishi, eventually closing down its blast furnaces in 1989; fishing shrank as new rules on exclusive economic zones kept Kamaishi’s fishing vessels closer to Japan.” In 1978, the central government began building the world’s deepest and most expensive breakwater in Kamaishi’s harbor, a plan intended to protect the city against tsunamis as well as to create jobs. But the breakwater, which took 30 years to complete, did little to stop Kamaishi’s economic slide. What’s more, after Japan’s economic bubble burst two decades ago, company executives could no longer hire geishas on their expense accounts, said Ms. Kanazawa of Saiwairo. On March 11, tsunami swept over and devastated Kamaishi, tearing apart the breakwater and reached far inland.

Tsunami Overcame Breakwaters, Embankments and Levees

The Sanriku coastal region of Tohoku (northern Honshu), where the tsunami struck, was equipped with highly advanced anti-tsunami measures constructed after previous disasters, including the Meiji-Sanriku quake in 1896, Showa Sanriku quake in 1933 and the Great Chilean Earthquake in 1960 that killed 142 people in Japan. These measures included seawalls, levees, dikes, embankments and breakwaters that had been built up over decades and cost billions of to build. After the 2011 tsunami left the region's towns covered in mud and debris from destroyed buildings, some survivors regret that too much confidence had been placed in the embankments. "We all believed tsunami would never reach our area," a resident of Rikuzentakata told the Yomiuri Shimbun. [Source: Hirofumi Morita, Fumito Nagase and Manabu Nakajo, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 17, 2011]

The world’s deepest breakwater — which stretched from the north and south sides of Kamaishi Bay — couldn’t with stand the momentum of the tsunami, which was compared to 250 jumbo jets flying ay 1,000kph. Completed in 2009 and designed to withstand the shaking and tsunami of an 8.5 magnitude quake, the two-kilometer breakwater was 20 meters thick and contained a foundation made of 7 million cubic meters of concrete. After the 2011 tsunami only sections of it were left and the concrete blocks exposed of the water surface faced all different directions. Tomoya Shibayama, a professor of ocean engineering at Waseda University, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “With all its destructive force, the tsunami apparently slammed into parts of the breakwater that had already been damaged by the quake and toppled them.” [Source: Yasuki Kaneko, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 22, 2011]

Damage in Ofunato The 1,960-meter-long embankment and breakwater at Kaimasha Bay was built at a cost of $1.5 billion over a 30-year period beginning in 1978 and was the nation's first embankment designed to resist the most powerful earthquake. Recognized in the Guinness World Records for being the world's deepest breakwater, it jutted out eight meters above the surface and had a foundation built on the seabed 63 meters below the surface of the sea. "Our embankment is the best in the world. How come we suffered that much?" asked a resident in Kamaishi. “I astonished because the breakwater hadn’t even wobbled during the previous tsunami,” another said. [Source: Hirofumi Morita, Fumito Nagase and Manabu Nakajo, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 17, 2011]

In Ofunato, Iwate Prefecture, many people were killed in the tsunami caused by 1960 Chilean quake. As a result, a large embankment was built at the mouth of the Ofunato Bay. According to the city's port and business department, the tsunami destroyed most of the 291-meter-long southern part of the embankment and all of the 243.7-meter-long northern part. [Source: Hirofumi Morita, Fumito Nagase and Manabu Nakajo, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 17, 2011]

The tsunami that inundated Ofunato reached a height of 23.6 meters. The 750-meter-long, 40-meter-deep breakwater at Ofunato Port was also annihilated. But some planning paid off. At Okirai Elementary School a passage was built from the second floor to a road lead to high ground to speed up evacuation in the event of a giant tsunami. Although the school building was destroyed on March 11 all of its students and teachers escaped unhurt.

The earthquake easily breached the 10-meter-high, 2.5-kilometer-long twin dikes in Miyako — known to locals as the “Great Wall of China — because their belief it would protect them — and destroyed the city and transformed into a muddy swamp. The dikes were completed in 1978 and had protected the town for 44 years. In Yamadamachi, a 50-meter to 60-meter section of the levee there collapsed under the power of the tsunami . In the wake of the disaster there that town was covered gray mud and littered with fishing boats and houses torn loose from their foundations. The floodgates and breakwaters in Minami-Sanrikucho — built over 50 years and designed to withstand a 5.5-meter tsunami — was equally ineffective against the March 11 tsunami. Minami-Sanrikucho was completed leveled and lost 10,000 of its 17,000 residents.

Tsunami Hits “Safe Village” on a Hill on an Island

Describing the experience of Georgia Robinson, an assistant language teacher from New Zealand in Nodamura, Iwate Prefecture, Aki Nakamura wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Everybody in the building was aware a tsunami alert had been issued after the massive earthquake that struck about 50 minutes earlier. But as most buildings in the village stood on a hill, and because they were about 800 meters inland, everyone continued to work as usual.” [Source: Aki Nakamura , Yomiuri Shimbun, April 25, 2011]

"What's that?" “Looking out the window, Robinson was confused by the sight of what looked to be a house moving. It took a few moments for her to process what she saw and understand that tsunami had hit the village. Inside the building, the people could hear nothing of the destruction occurring outside. Giant waves were sweeping away buildings amid an eerie calm... But the quiet only made things more frightening. From the second floor, Robinson could see the building was surrounded by dark, muddy water. The first floor was soon flooded. Debris smashed into the door. The sound of glass shattering rang out.” The building however withstood the tsunami and people inside sought safety in the upper floors.

“In the education board building, Robinson and others spent the night in pitch darkness on couches in an office on the first floor. They could not sleep at all due to frequent aftershocks. At 6 a.m. on March 12, Robinson went outside. In front of the local government office next door, Self-Defense Forces personnel were gathered for search and rescue work... Robinson joined others trying to clean up, but every time there was an aftershock they had to evacuate to a nearby gym. She saw bodies covered with blankets, and reflexively closed her eyes.”

Tsunami Damage in Rikuzentakata

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, Rikuzentakata “was once a fishing village of uncommon beauty, planted in a steep valley that descended to a seafront shaded by thousands of conifers. ..The official statistics issued here...stated that the tsunami had killed 775 people in Rikuzentakata and left 1,700 missing. In truth, a trip through the waist-high rubble, a field of broken concrete, smashed wood and mangled autos a mile long and perhaps a half-mile wide, leaves little doubt that ''missing'' is a euphemism...The surrounding hills were girdled by a bathtub ring of wreckage and felled trees at least 30 feet high...The ensuing tsunami gutted the B & G center — tossing the giant roof girders, pine trees and other debris into the pool — then rushed to Takata High, collapsing the gymnasium and wrecking all three stories of the school's main building. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, March 22, 2011

Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “The damage was particularly heavy here because Ayukawahama sits on the tip of a peninsula that was the closest land to the huge undersea earthquake 13 days ago. The resulting tsunami tore through the tiny fishing towns on the mountainous coastline, reducing Ayukawahama to an expanse of splintered wood and twisted cars. Three out of four homes were destroyed, forcing half of the town’s 1,400 residents into makeshift shelters. [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, March 24, 2011]

“At the offices of Ayukawa Whaling, only a light green harpoon gun — which once proudly decorated the entrance — and an uprooted pine tree were left standing. Across a parking lot stood the skeletal frame of the factory where whale meat was processed. A beached fishing boat and crumpled fire truck lay on the raised platform where the whales were hoisted ashore to be butchered....The company’s three boats, which had been sucked out to sea, washed up miles down the coast with remarkably little damage. But they remain grounded there. Ayukawa Whaling’s chairman, Minoru Ito, said he was in the office when the earthquake struck, shattering windows and toppling furniture. He led the employees to higher ground. All 28 of them survived, he said, though he later had to lay them off.”

Rikuzentakata

Schoolchildren Escape Tsunami in Kamaishi

Kamaishi is small coastal town in Iwate Prefecture that was devastated by the 1896 Sanriku earthquake and tsunami so people there — including school children who had been trained to look after themselves and not search for family members — knew what to do. Of the 2,900 primary and middle school children there only five were confirmed dead and they either left school early or were home sick on March 11. [Source: Sho Komine, Yasushi Kaneko, Yomiuri Shimbun , March 29, 2011]

On what the kids at two Kamaishi schools did, Sho Komine and Yasushi Kaneko wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Tsunami hit the Unosumaicho district in Kamaishi, with floodwaters reaching the third floor of Kamaishi-Higashi Middle School and the nearby Unosumai Primary School. Before the latest earthquake, the two schools jointly had conducted disaster exercises. At the middle school, the announcement system malfunctioned right after the earthquake and become unable to broadcast evacuation calls. However, students were able to quickly leave the building and gym as they had practiced, and grabbed the hands of primary school students — who were also on the verge of escaping from the building — and together ran up to higher ground.”

“One middle school first-grader, Dai Dote, 13, held the hands of two third-grade primary school girls. On their way up the hill, one of the girls cried and started hyperventilating, while the other became unable to speak. "It's OK," Dote told the girls as they ran to the top of the hill, more than two kilometers from their schools. Once confirming the safety of all their friends, the girls looked relieved, Dote said.

One teacher told the Yomiuri Shimbun, "I've repeatedly told children in class that we might experience tsunami larger than ever expected. It's almost a miracle that this many children were saved. I'm proud of the children for making [lifesaving] decisions on their own."

Stuck between the Ceiling and Water in Kamaishi

“When the massive earthquake struck the Unosumai district in Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture, Norikichi Ichikawa, 41, and his mother were evacuating to the district's disaster management center, where 54 people died in the ensuing tsunami,” the Yomiuri Shimbun reported. “Water broke the windows and entered the building, soon roiling up to the ceiling. Ichikawa's body floated on the surface, with his left side touching the ceiling. He almost was squashed by the rising water, but held his mother's hand tight.[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 30, 2011]

"I couldn't breathe. I thought I'd die. But I thought I had to save my mother's life at the very least," Ichikawa recalled. He gradually fell unconscious and thought, "This might be it." In the next breath, water receded to create a slight gap between the ceiling and water surface. He rose up to breathe as much as possible. The water kept receding, but his mother died, and many bodies were lying around him.

Furniture blocked the center's entrance. For two nights until being rescued, Ichikawa and 25 other survivors remained in the building. Ichikawa said he swallowed too much muddy water and passed black urine for three or four days. "I will live the rest of my life thinking of my mother, whose life was extinguished without mercy," Ichikawa said.

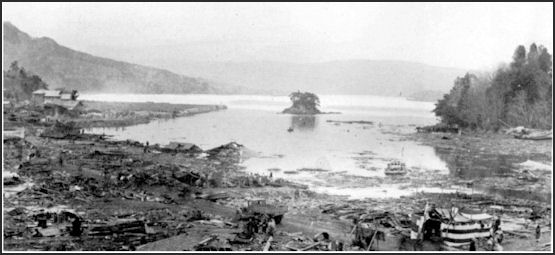

Kamaishi Bay 1933

Car Floats to 2nd-floor Height in Yamadamachi

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Yuko Ono, 39, of Yamadamachi, Iwate Prefecture, was driving a minivan when the tsunami hit the town. Her quick decision to drive her car into a narrow path saved the lives of three people. Ono was on the way home with her son, Kento, 8, and his classmate sitting on the backseat, when she witnessed a tsunami breaking down the several-meter-high waterfront dike and heading toward them.” "I thought we'd be washed away," Ono recalled. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 30, 2011]

“She put the car into reverse gear and entered a narrow path just wide enough for her car. Water surged into the U-shaped area, which was enclosed by houses. Within seconds, the van floated to a height equivalent to the second floor of the adjacent buildings, just like an elevator. The van was pushed up quickly and roughly, but walls of the surrounding houses prevented her car from tipping over. Ono's van drifted on the water like a boat for about 500 meters, getting stuck on a tree that stopped it from being washed away.”

“When the water receded, the vehicle "landed on" the debris without losing its balance. Many cars were washed away, lying around her van. Ono and the two children smashed the car windows to escape, and dashed uphill.” "We survived because of the surrounding walls," Ono said. "The wave hit the van not from the side but the front, and we didn't move. These factors might'vekept my van from overturning. ..When I almost gave up [on our lives], my son cheerfully said, 'We'll survive.' That helped me gain some hope," Ono said.

Using Sunlight as a Beacon in Miyako

“Fisherman Yoshinori Yamazaki, 62, was in Miyako, Iwate Prefecture when the tsunami struck, and was violently tossed about in the water,” the Yomiuri Shimbun reported. “While submerged, he tried to calm down and opened his eyes looking for the sunlight, to indicate the direction of the water surface to try to reach for air. Yamazaki struggled to break the surface but soon was dragged away by the water. He kept searching for the sunlight. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 30, 2011]

“When the tsunami surged toward him, Yamazaki hopped on the bed of a light truck and held the vehicle's rollover bar. He and the truck immediately were swallowed by torrents of water, and the high-pressure flow pulled his hands away from the post. The water current apparently was forming whirlpools, and it quickly and forcefully dragged Yamazaki down as he tried to emerge on the surface. He kept looking for the sunlight that would indicate the surface direction.” "I remember I tried doing that three times," Yamazaki said. But he then fell unconscious when his feet touched the ground as the water receded. He was rescued by local residents.

'Miracle of Kamaishi'

Although Kamaishi was struck by the catastrophic tsunami on March 11, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported, the great majority of the 3,000 primary and middle school students in the city fled to safety and were physically unhurt. Many children decided on their own that it would be risky to take shelter at designated evacuation sites, and instead made a beeline for higher ground to escape the oncoming tsunami. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 10, 2011]

For the last seven years, schools in Kamaishi have taught their students the basics of evacuation by inviting experts in disaster management as advisers to speak to the children. The golden rules drilled into the children were "Don't trust assumptions about disasters" and "Put yourself first and flee." The schools also incorporated content about disasters in each subject. One question in a mathematics class on velocity asked students to think about the speed at which a tsunami would reach the coast. The accumulation of these efforts resulted in the students swiftly evacuating in what has widely been referred to as "the miracle of Kamaishi."

Other ingenious methods have been employed elsewhere. In some places, children heard from elderly local people who experienced massive earthquakes in the past, while others drew antidisaster maps highlighting vulnerable areas by examining geographical features of their neighborhood. Some school athletic meets included bucket relay races and contests to build makeshift stretchers. These antidisaster education activities, however, have been held only in some regions, rather than nationwide.

Four-Year-Old Girl Loses Her Family in Miyako

A four-year-old girl in Miyako, Iwate Prefecture, who was swept away by a 30-meter that struck her house, which was thought to be safe because it near an evacuation center, was saved, it is thought, because here school backpack got entangled in a fishing net. She lost her mother and father and two-year-old sister though. Many newspaper readers shed tears when they read a letter the girl wrote to her mother which said: “Dear Mommy, I hope you are alive. Are you well?”

The girl, whose name in Manami, lived in a fisherman’s house on higher ground in Miyako. When the tsunami struck her family was in the yard and was swept away. Manami became entangled in a fishing net and was the sole survivor. Ironically her name means “Love the Sea.”

She fell asleep after that day, perhaps exhausted by everything that had happened. Later she finished he letter: “Thank you for [showing me] “origami and cats’ cradle and reading me books. She also penned a letter to her father, “Dear Daddy, please catch many fish, abalone and sea urchin and octopus and kombu.” In September, Manami told her grandmother, “Mommy has become a star.”

Flooding in Minato

Dog Saves Owner in Miyako

Reporting from Miyako in Iwater Prefecture,Toru Asami wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Babu does not normally like going for walks, but when the 12-year-old shih tzu insisted on going for one soon after the March 11 earthquake, her owner, Tami Akanuma, suspected something was amiss. And when Babu stubbornly headed for a nearby hill rather than taking their usual route in the coastal city of Miyako, Akanuma decided to follow along.” [Source: Toru Asami, Yomiuri Shimbun, March 28, 2011]

“Doing so may have saved Akanuma's life: Minutes after climbing the hill, a devastating tsunami slammed into the town, flattening the district of Taro-Kawamukai where they lived about 200 meters from the coast.” “Babu might have sensed a tsunami was coming,” said Akanuma, 83.

“Akanuma was relaxing in her living room when the quake struck off the Tohoku coast. The lights went out and Babu started scampering around the room, whimpering loudly and madly wagging her tail. “It's a bit early for a walk,” Akanuma thought, but she put Babu on her leash anyway. While they were in the entrance to Akanuma's home, a warning that a huge tsunami was heading for the Pacific coast was broadcast over the town's community speaker system.” Akanuma experienced the 1933 Showa Sanriku quake, which triggered a tsunami that left more than 900 people dead or missing in the Taro district. Her memories of that disaster meant they only had one option. “We need to evacuate,” Akanuma recalled thinking.”

As soon as she opened the door, Babu frantically ran outside and headed toward a nearby hill — the opposite direction they usually go for a walk. When Akanuma's pace slackened, Babu would look back, seemingly urging her owner to walk faster. When Akanuma caught up, Babu would bound ahead again, straining at her leash. This game of hurry-up-and-catch-me continued over and over. When Akanuma finally took a breather, she had climbed the hill where an evacuation center is located about one kilometer from her home. Turning around, Akanuma could barely believe her eyes: Most of the route she and Babu had walked had been swallowed up by the tsunami and her home had been consumed by the wall of muddy water.

Dead and Missing in Rikuzentakata

Todd Pitman of Associated Press wrote: “Immediately after the quake, Katsutaro Hamada, 79, fled to safety with his wife. But then he went back home to retrieve a photo album of his granddaughter, 14-year-old Saori, and grandson, 10-year-old Hikaru. Just then the tsunami came and swept away his home. Rescuers found Hamada's body, crushed by the first floor bathroom walls. He was holding the album to his chest, Kyodo news agency reported. "He really loved the grandchildren. But it is stupid," said his son, Hironobu Hamada. "He loved the grandchildren so dearly. He has no pictures of me!" [Source: Todd Pitman, Associated Press]

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “The official statistics issued here on Monday afternoon stated that the tsunami had killed 775 people in Rikuzentakata and left 1,700 missing. In truth, a trip through the waist-high rubble, a field of broken concrete, smashed wood and mangled autos a mile long and perhaps a half-mile wide, leaves little doubt that ''missing'' is a euphemism.” [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, March 22, 2011

“On the afternoon of Friday, March 11, the Takata High School swim team walked a half-mile to practice at the city's nearly new natatorium, overlooking the broad sand beach of Hirota Bay. That was the last anyone saw of them. But that is not unusual: in this town of 23,000, more than one in 10 people is either dead or has not been seen since that afternoon, now 10 days ago, when a tsunami flattened three-quarters of the city in minutes.”

Twenty-nine of Takata High's 540 students are still missing. So is Takata's swimming coach, 29-year-old Motoko Mori. So is Monty Dickson, a 26-year-old American from Anchorage who taught English to elementary and junior-high students. The swim team was good, if not great. Until this month, it had 20 swimmers; seniors' graduation cut its ranks to 10. Ms. Mori, the coach, taught social studies and advised the student council; her first wedding anniversary is March 28. ''Everybody liked her. She was a lot of fun,'' said Chihiru Nakao, a 16-year-old 10th grader who was in her social studies class. ''And because she was young, more or less our age, it was easy to communicate with her.''

Two Fridays ago, students scattered for sports practice. The 10 or so swimmers — one may have skipped practice — trekked to the B & G swimming center, a city pool with a sign reading, ''If your heart is with the water, it is the medicine for peace and health and long life.'' Ms. Mori appears to have been at Takata High when the earthquake struck. When a tsunami warning sounded 10 minutes later, Mr. Omodera said, the 257 students still there were ushered up the hill behind the building. Ms. Mori did not go. “I heard she was in the school, but went to the B & G to get the swim team,” said Yuta Kikuchi, a 15-year-old 10th grader, echoing other students' accounts. Neither she nor the team returned. Mr. Omodera said it was rumored, but never proven, that she took the swimmers to a nearby city gymnasium where it has been reported that about 70 people tried to ride out the wave.”

Describing the scene at the place where bodies were identified Wines wrote: “In the Takata Junior High School, the city's largest evacuation center, where a white hatchback entered the school yard with the remains of Hiroki Sugawara, a 10th grader from the neighboring town of Ofunato. It was not immediately clear why he had been in Rikuzentakata.'This is the one last time,' the boy's father cried as other parents, weeping, pushed terrified teenagers toward the body, laid on a blanket inside the car. 'Please say goodbye!'

Firefighters That Died in Kamaisha and Miyako

Tomoki Okamoto and Yuji Kimura wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, Although volunteer firefighters are classified as temporary local government employees assigned to special government services, they are basically everyday civilians. "When an earthquake occurs, people head for the mountains [due to tsunami], but firefighters have to head toward the coast," said Yukio Sasa, 58, deputy chief of the No. 6 firefighting division in Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture. [Source: Tomoki Okamoto and Yuji Kimura, Yomiuri Shimbun, October 18, 2011]

The municipal government in Kamaishi entrusts the job of closing the city's 187 floodgates in an emergency to the firefighting team, private business operators and neighborhood associations. In the March 11 tsunami, six firefighters, a man appointed fire marshall at his company, and a board member of a neighborhood association were killed.

When the earthquake hit, Sasa's team headed toward the floodgates on the Kamaishi coast. Two members who successfully closed one floodgate fell victim to the tsunami — they were most likely engulfed while helping residents evacuate or while driving a fire engine away from the floodgate, according to Sasa."It's instinct for firefighters. If I'd been in their position, after closing the floodgate I would've been helping residents evacuate," Sasa said.

Even before the disaster, the municipal government had called on the prefectural and central governments to make the floodgates operable via remote control, noting the danger aging firefighters would face if they had to close the floodgates manually in an emergency.

In Miyako in the prefecture, two of the three floodgates with remote control functions failed to function properly on March 11. As soon as the earthquake hit, Kazunobu Hatakeyama, 47, leader of the city's No. 32 firefighting division, rushed to a firefighters' meeting point about one kilometer from the city's Settai floodgate. Another firefighter pushed a button that was supposed to make the floodgate close, but they could see on a surveillance monitor that it had not moved.

Hatakeyama had no choice but to drive to the floodgate and manually release the brake in its operation room.He managed to do this and close the floodgate in time, but could see the tsunami bearing down on him. He fled inland in his car, barely escaping. He saw water gush out of the operation room's windows as the tsunami demolished the floodgate.

"I would've died if I'd left the room a little bit later," Hatakeyama said. He stressed the need for a reliable remote control system: "I know there are some things that just have to be done, regardless of the danger. But firefighters are also civilians. We shouldn't be asked to die for no reason."

Image Sources: 1) May Japanese Guest Houses 2) itako 3) Aomori City site 4) Aomori Museum site 5) Onsen Express 6) 7) Hirosaki City site 8) 9) Akita Prefecture site 10) 11) Sendai City site 12) 13) Wikipedia 14) Japan National Parks site 15) 16) Yamagata Prefecture 17 ) Samurai Dave blog 18) Aizu Wakamatsu city 19) Niigata city site 20) 21) Sado Island site

Text Sources: JNTO (Japan National Tourist Organization), Japan.org, Japan News, Japan Times, Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan Ministry of the Environment, UNESCO, Japan Guide website, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020