LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT IN JAPAN

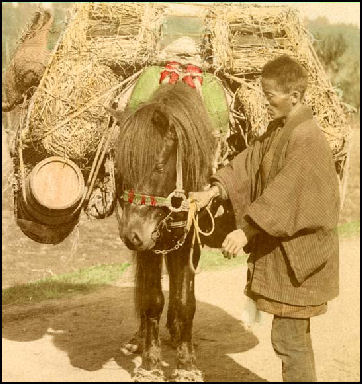

Kago bearers in the 1800s Japan’s employment system played a central role in the strong economic growth that the country achieved in the second half of the 20th century. The system was supported by three pillars: lifetime employment, seniority-based wages, and enterprise-based unionism. To these, a fourth pillar was later added: community consciousness within the company, one based on vertical relationships, reciprocal obligations, and decision-making by consensus. The traditional system described in the first section below is still considered the ideal by many people. In the difficult economic environment that exists in Japan today, however, employment patterns are undergoing significant changes. Even among major corporations long considered bastions of Japanese-style management, organizations strictly following traditional practices are becoming increasingly rare. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Labor distribution follows the pattern set by other industrialized nations. While agriculture and other primary-sector industries employ fewer people, services and other tertiary industries show an increase. Employment in primary industry fell from 32.7 percent of the working population in 1960 to 4.2 percent in 2008. Over the same period, tertiary occupations rose from 38.2 percent of the total to 68.5 percent. A vast majority of Japan’s working population is made up of salaried workers. In 2002, 84.2 percent of the total population worked at salaried jobs.

Labor force: 25 percent industry; 5 percent agriculture; and 70 percent services. About 93 percent of men between 25 and 54 have a job in Japan. This is one of the highest rates in the world. Nonregular workers accounted for 38.7 percent of Japan’s total workforce and part-time workers made up 22.9 percent of all workers as of October 2010. Regular workers accounted for 61.3 percent of Japan’s total workforce Small and mid-size companies employ 65 percent of the workforce in Japan.

The Labor Standards Law of 1947 contains a “bill of rights” for workers that guarantees minimum wage, maximum hours of work and so on. The rules about long hours are often overlooked.

According to a survey among 1,000 elementary students in 2003, the dream job for boys was to be a professor or a soccer player, for girls it was to run a restaurant or be a nurse.

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare mhlw.go.jp/english ; Japan Institute for Labor Policy and Training jil.go.jp/english/index ; Japan Institute for Workers’s Evolution jiwe.or.jp ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Labor Chapter stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ;2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp ; Physician Job Satisfaction and Working Conditions in Japan pdf file joh.med.uoeh-u.ac.jp/pdf ; International Study on Working Conditions of School Personnel pdf file nfer.ac.uk/nfer/publications ;Wages and Pay in Japan jetro.go.jp/en ; Average Pay and Expenditures worldsalaries.org/japan ; RENGO Japanese Trade Union Confederation jtuc-rengo.org/ ; NPR Story on Unemployed Temporary Workers www.npr.org

Links in this Website: LABOR, UNEMPLOYMENT AND UNIONS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; WORKERS AND THEIR COMPANIES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FREETERS, TEMPORARY WORKERS AND FOREIGN WORKERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; WORKING WOMEN IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SALARYMEN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Hard Work and Education in Japan

Japanese workers really hustle. Garbage collectors, gas station attendants, waitresses and even dental workers and McDonald’s employees run around when they work. One psychologist told the Los Angeles Times, "When Japanese are not working they feel guilty.” Japanese have little patience for people who are lazy, break promises or who do not try their best. They resent poor service as a personal insult.

laborers in the 1800s A great emphasis is put on being busy. Unlike Americans who tend to look at work as a means of reaching a goal, Japanese often regard work as an end to itself, a kind of existential existence. When one goal is reached it time to move on to the next one. Children learn early in school that hard work is a virtue. They like helping out and do so with great enthusiasm and pleasure.

The rich and highly regarded Japanese investor Nobuyuki Koga told the Times of London that Japanese “employees are ambitious, and we are fortunate to have people that naturally work extremely hard. On the one hand, there is also a pioneer spirit that exists...while people really are deeply concerned about providing clients with the best service possible.”

Hard work doesn’t bear as much fruit as it once did. Sometimes it seems like the economy would be better served if Japanese spent more time enjoying themselves and spending money and generating domestic demand rather than working.

Japanese are well educated. One scholar told U.S. News and World report that "when you sit down with Japanese blue-collar workers in a quality-control circle, you hear discussions at levels you'd expect from Americans who have gone through four years of engineering school."

Training is often done through apprenticeship-like systems. In some trades trainees are expected to “learn and steal” the trade from their masters.

Hazing of new employees is not unusual. In December 2009, four trainee firefighters received ¥6.6 million in compensation for a hazing incident that caused them to resign.

Comparing Attitudes About Work and Play in Japan and the U.S.

“Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “The poster boy for American diligence is undoubtedly the 18th-century statesman and inventor Benjamin Franklin. His values of hard work and frugality became embedded in American culture, particularly through the many proverbs he recorded in his Poor Richard's Almanack, such as "Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise." Kishichi Watanabe, a business historian, has compared Franklin's way of thinking with that of Ishida Baigan, a Japanese business philosopher who was active right around the same time as Franklin. Baigan established the Sekimon Shingaku movement, which with government support became the most prominent educational establishment of the merchant class in the 18th century. Watanabe suggests, however, that while both Franklin and Baigan advocated many similar values, Franklin additionally espoused self-assertiveness and individuality, while Baigan promoted submission and loyalty. It is possible that the differing philosophies of these thinkers contributed to the divergent notion of diligence in the two cultures. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, February 14, 2012]

“The 2010 Asia-Pacific Value Survey conducted by the Tokyo-based Institute of Statistical Mathematics asked 1,002 American adults and 1,800 Japanese adults to respond to 54 questions, choosing from a number of set responses. Regarding a question about their attitude toward life, roughly half of both groups chose "Lead an honest and ethical life." The second and third most common responses for the Japanese group were "Don't think about money or fame; just live a life that suits your own taste" (21 percent) and "Live each day as it comes, optimistically and without worrying" (14 percent).

“These were also the next two most prevalent responses for the Americans, although the order of frequency was reversed, with 20 percent taking each day as it comes, and 16 percent not thinking about money or fame. Eleven percent of the Japanese chose "Make a social commitment by being active in volunteer work," but only 4 percent of the Americans selected this as best reflecting their life attitude. "Make a name for yourself by studying earnestly" received the lowest frequency rate for both groups, at 2 percent for the Americans and 1 percent for the Japanese.

“Another question asked whether, if the respondents had enough money to live comfortably for the rest of their lives, they would continue to work. The majority of both groups said they'd continue to work, but the Japanese percentage was a bit higher: 63 percent compared to 56 percent for the American responses.

“There was more variation regarding the most important factor in work, although not necessarily pointing to a greater emphasis on diligence among Japanese compared to Americans. Of four choices, the top response for the Americans was "a good income so that you do not have to have any worries about money," with 35 percent answering in this way, but this was the choice that had the lowest percentage frequency for the Japanese respondents, at 16 percent. The Japanese respondents' most common choice was the same as the Americans' second choice: "Doing an important job which gives you a feeling of accomplishment," with 39 percent and 32 percent respectively. The Japanese respondents' second choice, "Working with people you like," selected by 24 percent, however, was the last choice for the Americans, with a frequency rate of only 9 percent.

Population Declines and the Japanese Workforce

There is growing concern over the consequences that the aging of Japanese society will have for the economy. In 2011 approximately 23 percent of the population was 65 or older, but by 2055 this figure is projected to be about 41 percent. To minimize the effects of the contraction of the working population, it will be necessary to both increase labor productivity and to promote the employment of woman and people over 65. In addition, fundamental reforms will be necessary in pension and other social welfare systems in order to avoid large inequalities between generations with respect to the burdens born and benefits received.

A declining birthrate and an older population means that as time goes on there will more retired people and relatively less working people, which means that working people are increasingly called upon to support the retirees with their labor. Between 1985 and 2005 the number old elderly doubled while the number of children fell by a third. By one count the Japanese workforce will shrink by 6.1 million by 2025. This will put a lot pressure on younger people to take care of older people. Japan will have allow large numbers of immigrants in if it wants to maintain economic growth.

The work force is expected to fall 15 percent over the next 20 years and halve in the next 50 years. Currently, about 70 percent of the population in Japan is of working age. By 2025, if current trends continue, the figure will drop to 60 percent. That means that in 2025 three working people will not only have to support themselves they also have to support two people who aren't working. By 2050 population loss will strip Japan of 70 percent of its workforce.

A shrinking, graying population is likely to cause the economy will shrink. There will be fewer skilled people entering the job market. There will be less savings. This means there will be less money for loans and investmnet and this will make it harder for companies to grow and create new jobs for young people.

Japan’s aging population is also widely seen as an obstacle to innovation. As the population gets older and fewer young people are born there are less young people around to come up with fresh new ideas and more cranky old people around to pooh pooh the fresh ideas that appear.

Japan will probably have allow large numbers of immigrants in if it wants to maintain economic growth.

Retirement and Labor Shortage in Japan

The retirement age in 1995 was 66.5 compared to 67.2 in 1960. About 350,000 people retired a year in the 1990s. There was a sudden surge of retirees in 2007 to 500,000 a year as some of the seven million Japanese baby boomers, defined as those born between 1947 and 1949, began retiring.

Japanese are required to retire when they are 65. Surveys indicate that many Japanese believe that raising the retirement age is the best way for the government to finance services of its aging population.

Ratio of workers to retirees in 1995: 2.6 to 1. Expected ratio of workers to retirees in 2050: 1.5 to 1.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the longest working career belonged to Shihechiyo Izumi who began working and loading animals at a sugar mill in 1872 and retired as a sugar cane farmer in 1970 at the age of 105, after working for 98 years.

There are labor shortages in agriculture, fishing, factories, restaurant, nursing homes, construction and forestry. The labor shortage is expected to get worse as more Japanese baby boomers retire. They began retiring en masse in 2007

Working Hours in Japan

laborers in the 1800s Work week: 46.5 hours, compared to 40.3 hours in France and 55.1 hours in South Korea. [Source: Roper Starch Worldwide, based on interviews in 2001 and 2002]

Japan used to have a 44-hour work (8 hours on weekdays, plus 4 hours on Saturday), the longest of leading industrialized nations. These days many workers have Saturday off but a lot still work on that day.

The average full-time Japanese worker worked 2033 hours in 2007, compared to 1,912 hours in 1996 and 2,470 on 1988. The average work week in 1900 was 51.7 hours.

Many workers work overtime and receive no extra payment. Even though many workers are promised a three week holiday many people don't take all of the time they are promosed. Surveys show that workers have less free time every year and there is a widening gap between those who work all the time and those that have a lot of time off, namely retirees.

See Labor, Salarymen, Long Hours

Vacation Time in Japan

According to one survey the average worker in Japan gets 11 days of paid vacation and 14 holidays, compared to 30 days of paid vacation and 10 holidays in Germany, 27 vacation days and 11 holidays in Sweden, 25 vacation days and 10 holidays in France, 27 vacation days and 8 holidays in Britain, 12 vacation days and 11 holidays in the United States.

In 2007, the average number of annual paid holidays was 17.7 days, a record low. On average employees took 46.6 percent of their paid holidays. This rate has steadily been declining since a peak of 56.1 percent of paid holidays in 1993. These figures reflect 1) the difficulty that workers have using their paid holidays; 2) the fact they have so much work they need vacation time to do it; and 3) the difficulty of finding people to take their place while they on vacation.

In 1998, on average, workers were entitled to take 17.5 days off from work but only took 9.1 days. In 1980 they took 61.1 percent of their vacation time. By contrast the French and Germans take all of six weeks of vacation they are allowed. Americans take three quarters of the 17 days they are allowed.

Salarymen have difficulty taking time off in a culture that emphasizes hard work and self-sacrifice. They feel guilty if they take off while their coworkers are working. When people do take time off it is often for an obligation such as a wedding or funeral or a summer vacation when everyone in the office takes a vacation at the same time. Some workers have never taken a vacation with their families and can’t imagine taking one.

The recession in the 1990s pushed many companies to shorten the working hours of their employees and give them longer vacations. The Marui Department Store chain began giving its employees a month of vacation time every year. Sapporo Breweries began allowing its employees to spend two or three month doing Peace Corps-like volunteer work in developing countries.

Economists would like to see Japanese workers take more time off and spend more money in their free time. According to one government report: “If people took their paid holidays fully, the economic ripple effects to travel and leisure activities would rise to ¥12 trillion.” As part its work-life balance program the government is trying t get workers to reduce the number of hours of overtime, use their paid holidays and spend more time with their families. In 2009, Japanese workers got an average of 7.8 days of summer vacation.

See People, Holidays, Vacations

Lack of Sleep for Busy Tokyoites

According to a survey by Japanese foodmaker Ajinomoto, working people in Tokyo get less sleep (slightly less than 6 hour a day) than working people in New York, Paris and Stokcholm. People in Shanghai got the most sleep (seven hours and 28 minutes). In New York the business people surveyed goy six hours and 35 minutes. [Source: Reuters Life, December 8, 2010]

"I think people in Tokyo may just be too busy," an Ajinomoto spokeswoman told Reuters. "In Tokyo, on top of the long days, people seem to do things after they get home as well, like playing computer games. They don't sleep until after midnight."

Reuters Life reported: “Many Japanese businesspeople are forced into long days by hours of overtime followed by after-hours drinking sessions and then a long commute home, although the survey found that commutes in New York were about equally long. Tokyo trains in both mornings and evenings are full of dozing commuters, heads bobbing. Some even manage to nap standing up as they cling to overhead rails.”

“Not surprisingly, when asked what was most important in their lives, Japanese gave "sleep" the top ranking — the same as their Parisian peers, who nonetheless got nearly seven hours of sleep on weekdays. By contrast, both New Yorkers and Shanghai residents said "time with their family" came first. The survey was conducted online between July and August, covering nearly 900 workers in their 30s to 50s.”

Working Less in Japan

More and more workers are choosing to work less time, even it means less money, to spend more time with their families, attend graduate school classes and pursue interests outside of work. A 2008 Labor Ministry survey revealed that 28.9 percent of businesses had shorter working hours than before.

A sales representative at Pfizer who works from 10:10 am to 4:00pm told the Yomiuri Shimbun , “I have more time to take care of my children and at the same time I can enjoy my job more, meeting many clients and helping people suffering from diseases.” An employees at a software development company who decided to get an advanced degree in business said, “I thought it’d be physically demanding to both go to grad school and work full-time, Thanks to this system, I’ve been able to get a Masters of Business Administration [degree] and stay healthy.” On how she managed things with her co-workers she said, “I tried not to bother them as much as possible by voluntarily working overtime when I didn’t have any classes.”

The government has declared shorter working hours to be the most important element in realizing an improved quality of life for the Japanese people. Revisions to the Labor Standards Law, a trend toward adoption of a five-day work week, and such measures as allowing for substitute holidays when a national holiday falls on a Sunday have contributed to shorter working hours. Annual working hours, which were 2,110 in 1985, stood at 1,754 in 2010. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Wages and Bonuses in Japan

The Japanese wage system has traditionally been closely linked to the seniority system. Wages are often still strongly influenced by an employee’s length of service. Salaried workers normally receive a monthly salary plus two seasonal bonuses. Particularly in large companies, the bonus system plays an important role. In 2010, bonuses amounted to about one-third of annual base wages. Through the diversification of society, employment has been taking on new forms, including the popularization of freelance employment and the introduction of outsourcing. In response to such changes, the wage system has also been diversified. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Averages monthly wages were ¥268,010 in September 2010. In February 2010, wages declined for a record 21st straight months. In 2009, monthly wages fell a 3.3 percent to ¥315, 311. It was the third consecutive year they fell. Basic salaries fell 1.1 percent and bones and overtime pay fell 10.8 percent and 7.9 percent respectively.

In 1993, the average Japanese worker got $11.50 in wages and $4.40 in benefits per hour compared to $14 in wages and $10.70 in benefits per hour in Sweden, $11.90 in wages and $9.60 in benefits per hour in the Netherlands, $9.30 in wages and $8.50 in benefits per hour in France, $14.60 in wages and $4.60 in benefits per hour in Germany, $14.40 in wages and $12.50 in benefits per hour in the U.S., $9.00 in wages and $5.70 in benefits per hour in Spain, and $10.20 in wages and $4.40 in benefits per hour in Britain. [This data is old but useful for comparisons]

Many Japanese get a large chunk of their salary in the form of semi-annual bonuses at the end of year and in the summer. In 2008, the average summer and winter bonus were each around ¥900,000 (about $9,000) at big companies. The average summer bonus in 2009 was ¥363,104, down 9.7 percent from the previous year. The average winter bonus was ¥747,282, 15.9 percent lower than the previous years, the sharpest decline since 1959.People in non-managerial administrative positions in the central government were given ¥692,900 while those the same position in local government received ¥655,000. The highest government bonuses of ¥5.1 million went to Supreme Court justices. The Prime Minister got ¥4.1 million

Bonuses in the summer of 2010: 1) ¥427,822 in industry and mining; 2) ¥ 616, 900 in finance and insurance; 3) ¥291,096 in the wholesale and retail industry; 4) ¥280,224 in health care and welfare industry. In 2011, summer bonuses at major Japanese company rose 4.17 percent to an average of ¥809,604. In 1996, the average bonus was $6,950 for government employees and $5,200 for private sector employees. A large share of the bonuses are often spent on gift boxes of sushi, sake, sweets or fruit given to family, good friends, doctors, teachers, employers, special customers and other people considered special.

Labor unions are often the ones that demand that companies keep automatic seniority-based pay hikes. Companies customarily decide wage levels through negotiations between labor and management. The word “shunto” describes the spring negotiations between management and labor unions for wage hikes. In recent years there has been a movement away from this custom in favor of giving dividends to stockholders. Management has been resistant to the idea of giving workers regular pay hikes while unions want companies to give a share of their profits to workers.

Employees are given money to cover their travel expenses. In some cases employees who walk to work have the cost of their new shoes covered.

Minimum Wage in Japan

A law was passed in November 2007 to raise the minimum wage a token amount, slightly above welfare payments.

In Japan, the minimum wages varies regionally. The national average in 2007 was ¥687. In Tokyo it was ¥739. This is way below levels in Europe. The minimum wage in Britain, for example, is the equivalent of ¥1,250. As of 2009, the minimum wage was lower than welfare payments in nine prefectures.

Some analyst believe that raising the minimum wage significantly would help the Japanese economy by 1) giving low-wage workers more money and increasing their consumption, and 2) filling positions in jobs for which there is a shortage of workers because the pay is not high enough and foreign workers are unavailable.

Stricter rules about overtime pay are being put on the books. The Labor Standard Law was revised in December 2008 to raise the rate for overtime work to 50 percent or more of regular pay from the 25 percent or more.

Convenience store workers get $8 an hour.

Uniforms in Japan

The Japanese are big on uniforms. They are worn by workers of all sorts of different occupations, from office ladies and department store workers to machinists and engineers. They are useful in saving money on clothes and helping customers identify workers. Some people complain that uniforms promote rigidity and stifle individuality.

Carpenters and construction workers in Japan often wear a strange get up consisting of super baggy parachute-style pants tied at the ankles and mitten-like shoes that fit separately around the big toe and other toes and look like something a scuba diver would wear.

Workers often wear a “hopi”, a short blue cotton jacket with an insignia of the workers trade or company. It has traditionally been worn with short tight cotton pants called “momohiki”.

Many Japanese workers wear a suit for the commute to their job site and then change into a company uniform more practical for doing physical work or working in a workshop or laboratory.

Image Sources: 1) 2) 4) 5) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 3) 8) Ray Kinnane 6) Rob's Gallery, The Faq Japan 7) Goods from Japan 8) Twin Isles

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2012