JAPANESE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS

There are about 30,000 primary and middle schools in Japan. Japanese elementary schools resemble American elementary schools in many ways. The classrooms look similar and students push and shove and fight in the halls. Young Japanese elementary school students wear matching-colored caps in sports class and walk to school with heavy backpacks strapped over their shoulders. During the frigid Japanese winters they often run around the playground in their shorts, partly to build character. Young elementary school students often attend school for only half a day. Older elementary school children often stay in school until around 4:00pm.

In 2003 there were 7,226,911 students in elementary schools. Japanese children enter primary school from age 6. The average class size in suburban schools is between 35-40 students, though the national average had dropped to 28.4 pupils per class in 1995. 70 percent of teachers teach all subjects as specialist teachers are rare in elementary schools. 23.6 percent of elementary school students attend juku (mostly cozy family-run juku). Suburban schools tend to be large with student populations ranging from around 700 to over 1,000 pupils, while remote rural schools (19 percent of schools) can be single-class schools. [Source: Education in Japan website educationinjapan.wordpress.com **]

“The curriculum includes the following subjects: Japanese language, social studies, arithmetic, science, life environmental studies, music, arts and crafts, physical education, and homemaking. Requirements also include extracurricular activities, a moral education course, and integrated study, which can cover a wide range of topics (international understanding, the environment, volunteer activities, etc.). Reading and writing are perhaps the most important parts of the elementary school curriculum; in addition to the two Japanese syllabaries, students are expected to learn at least 1006 Chinese characters by the end of the sixth grade.

There are no substitute teachers in Japanese elementary schools. When the teacher is absent, students generally take care of themselves. A teacher or principal often looks after the first and second graders but the third, forth, fifth and sixth graders are often left for hours without supervision, and work quietly on their own.

Students have traditionally been evaluated with report cards that gave students three grades: “excellent,” “good” and “needs more improvement.” In recent years the trend has been for report to offer more details with both numerical grades and descriptive evaluations.

Primary Education in Japan

Attendance for the six years of elementary education is compulsory. Ninety-nine percent of elementary schools are public coeducational institutions. A single teacher is assigned to each class and responsible for instruction in most subjects, with the exceptions generally being subjects such as music and art. In 2011, the maximum class size at a public elementary school was 35 for 1st-grade classes and 40 for other grades. In principle, classes are not segregated based on student ability, but for instruction in certain subjects students might be divided up into groups taking proficiency level into account. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Ninety-nine percent of elementary schools are public schools, and each municipal board of education supervises all public elementary schools under its jurisdiction.4 The municipal boards of education are overseen by the prefectural board of education, which is responsible for the employment, assignments, and salaries of teachers. The MOE subsidizes the educational expenses of the prefectural governments that have insufficient budgets for education expenses, in order for all children in the nation to receive the same quality of education. All school-aged children are assigned to a school in their locality. All children study the same curriculum based on national standards from teachers with a uniform set of qualifications. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Teachers are periodically rotated among the schools in their district in order to keep the quality of the instruction equal. However, some regional discrepancies in academic achievement and college enrollments are well attested. The students in urban areas are more likely to attend colleges than those in rural areas. However, this has less to do with the quality of the schools or the teachers than with cultural and socioeconomic differences. The degree of educational aspiration in the urban communities is generally higher than in rural communities. ~

The strict division of elementary school districts based on egalitarianism (one elementary school per district) became looser in an era of deregulation and decentralization. Responding to the 1997 deregulation of the school district system by the MOE and to the growing popularity of private schools, the Shinagawa Ward in Tokyo introduced a school choice system in public schools. In April 2000, Shinagawa Ward created four large districts comprising forty elementary schools, any of which parents can choose. Since April 2001, parents can also choose a middle school among 18 public middle schools in the Shinagawa Ward. On April 1, 2001, 21.1 percent of Shinagawa Ward’s elementary school students and 28.1 percent of its middle school students attended schools outside of their designated districts (MKS July 10, 2001). The Shinawaga Ward also plans to establish a nine-year school that combines elementary and middle schools in 2006, in order to have a more flexible curriculum and to compete with private schools (AS January 18, 2002). Since April 2002, the Shinawaga Ward introduced an evaluation system run by parents and local residents who visit the school. ~

Education Requirements in Japanese Elementary Schools

All public elementary schools are required to design a curriculum based on the MOE’s Course of Study. The national standard of education guarantees a high quality education to all students. However, the rigidity of the school curriculum has impeded the individuality and creativity of students. In 1987, the National Council on Educational Reform (Rinkyo-shin), commissioned by Prime Minister Nakasone, criticized the uniformity of education, and recommended the diversification of primary and secondary school curricula and that the deregulation of the educational system (Monbusho- 1989). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The 1989 Course of Study for 1992-2001 was issued in accordance with the recommendation. The 1998 Course of Study for 2002 onward emphasizes further deregulation, diversity, and individuality. The 1998 Course of Study also reduces the content of the curriculum by 30 percent, and allots 20 percent of class hours to review sessions, in order to emphasize basic knowledge for all students. Many teachers are worried that such a reduction of educational content will interfere with student’s academic progress. According to a 2002 survey, the test scores of elementary school students on the 100-point mathematics test was 10.7 points lower than the scores of those who had taken the test in 1992 (AS September 23, 2002). ~

Responding to public concerns about lowering academic standards, many public schools found ways to increase the number of academic class hours by shortening school events, providing a summer session, and having parents and community leaders teach Saturday classes (AS May 6, 2002). Furthermore, the MOE plans to create a special study group for advanced students, by adding one more teacher to each of the 846 model elementary and middle schools (increasing to 1,692 schools and 20 high schools in the 2003-2004 year) (AS August 18, 2001; AS August 17, 2002). ~

Decreasing Number of Elementary School Students and Class Size in Japan

The number of elementary school students has been decreasing for eighteen consecutive years, due to the lowered rate of childbirth. In 2002, there were approximately 7,239,000 students in elementary schools, about 61 percent of 11,925,000 students (the second generation of baby boomers) recorded in 1981 (Monbukagakusho- 2002a). In recent years, many elementary schools have been closed or merged with other schools because of the shortage of students. Many elementary schools have empty classrooms, which have been converted into computer rooms, international understanding rooms, and even into rooms open to the general public. Since 1993, the government has promoted the use of school facilities for the community (Monbusho- 1999b:10). Responding to the growing elderly population, schools such as Yushima elementary school in Tokyo have converted parts of their facilities into a nursing home (Kaplan et al. 1998:96). Such an arrangement promotes intergenerational communications. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

The declining number of students also caused higher competition for teaching positions, and in 1999 only one-third of the people graduating from national universities with degrees in education found teaching positions (AS September 19, 1999). In 2001, the average teacher was 43.8 years old (Monbukagakusho- 2003a). Growing age difference between elementary students and teachers may cause miscommunications and problems in classroom management. ~

The average number of students per class is 26.5, and the student-teacher ratio is 17.5:1 (Monbukagakusho- 2004a). The current maximum class size of 40 prevents teachers from paying enough attention to individual students. Teachers also have heavy workloads when they grade the homework, quizzes, and examinations of 40 students, write daily notes to each student and complete all of the administrative paperwork. One principal told me that it is impossible to give each of the 40 students individual attention and meet all of their needs. Making classes smaller is at the top of the lists of demands of elementary school reformers. ~

Since April 2003, each prefectural board of education has had the right to reduce class size to fewer than 40 students, but the prefecture has to pay for the extra teachers. Following the recommendation of the Research Survey Group, the MOE started to allow schools to experiment with smaller classes. In April 2001, five prefectures authorized class sizes of under 40 students, especially for first graders (AS May 12 2001). A year later, sixteen prefectures planned to enforce a smaller class size policy, including six prefectures implementing smaller class sizes for middle school students (AS March 10 2002). Yamagata prefecture planned to implement a class size of fewer than 21 to 33 students for first to sixth graders by adding 223 teachers over the next few years (AS January 10, 2002). After April 2002, sixteen prefectures decided to keep classes between 30 and 38 students, especially for the first graders. Six prefectures have similar plans for middle schools (AS March 10, 2002). ~

The MOE rejected the Group’s proposal for a 30-student class, arguing that it would require about 120,000 teachers and an additional trillion yen. The Group also recommended that the homeroom class, the core of elementary school education, could be dissolved and regrouped into a different class for certain subjects. Then, the MOE decided to increase the number of elementary and middle school teachers to 22,500 over five years, beginning in the 2001-2 school year, in order to assign two teachers per class in the lower grades, and divide a class into two for mathematics and English in elementary and middle schools (AS October 14, 2001). Classroom aides and volunteers would assist teachers in the classroom and after school.5 The MOE plans to hire approximately 50,000 teachers’ aides to work in elementary and middle schools over the three years starting in 2001, and to promote the volunteer system (Monbukagakusho- 2003b:62-63). Furthermore, the MOE plans to send college students who are majoring in education to elementary and middle schools to tutor students after school (AS August 17, 2002). It will reduce costs if schools become more open to the community, and recruit classroom aides and volunteer helpers from the large local pool of highly educated homemakers. Many such volunteers are now active in after-school programs and integrated study. The practice of using of school support volunteers has spread across Japan. ~

Unused schools are being turned into indoor lettuce farms and ham factories.

Class Size of Second Graders Limited to 35 in 2012

In December 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The government plans to limit the number of second-year students at public primary schools to 35 per class starting in the 2012 academic year, sources said.The system was introduced for first-year students at public primary schools in the 2011 school year. To realize the plan, the government plans to employ about 1,000 more teachers, appropriating the necessary outlay in the fiscal 2012 budget, without revising the current law. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 18, 2011]

“The 35-student class system is aimed at providing individual students with better guidance by reducing the number of students from the standard 40 per class to 35.The Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry wanted to introduce the system for both first- and second-year primary school students in the 2011 school year. However, the system was introduced only for the first-year students because the Finance Ministry objected to the higher personnel costs needed to hire more teachers and administrative staff.

“The 35-student class system was introduced to help solve the so-called first-year student problem, under which children entering a primary school find it difficult to adapt to school life.About 4,100 extra teachers would be needed if the 35-class system for second-year students was made permanent, as the law regulating class sizes would have to be revised.

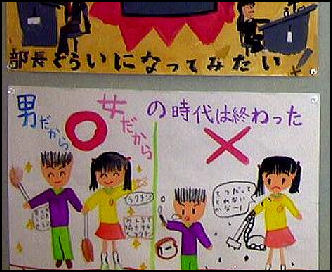

Equality in Japanese Elementary School Education

Elementary school education is based on “whole person education,” the development of the child’s character in cognitive, moral, emotional, and physical areas. It emphasizes egalitarianism and group consciousness, and rejects tracking or ability grouping. All children are assumed to have the potential to develop their own abilities and skills, and education is intended to help them develop their potential. [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

All public school students receive the same education based on almost identical textbooks and a shared curriculum. Japanese textbooks are slim, only about 100-200 pages long, and are supplied to all elementary students and middle school students at no charge. The MOE checks the factual accuracy of the textbooks through a formal authorization system. Teachers design their lesson plans on the basis of the national standards outlined in the Course of Study. Teachers deliver knowledge of academic subjects through textbook-centered class instruction. The current educational reform advocates criticize a uniform curriculum and textbook-centered pedagogy as undermining children’s creativity and individuality. These criticisms were the rationale for the creation of “integrated study” and “social experience” pedagogy. ~

Japanese Elementary School Values

Elementary school classrooms are filled with slogans like "Doing Out Best is Everything," and "Active and Cheerful, and Friendly and Helpful." Part of the daily routines is taking a show of hands to find out if anybody was late or had forgotten their book. Students that have committed an offense fess up to it and express “hansei”, a kind apology and act of contrition. [Source: Nicholas Kristoff, New York Times]

Describing how a group of Japanese children were taught to dive off a high diving board at a swimming pool, Downs wrote: "Grouped by age, not ability, the children were clearly apprehensive, while their teacher demonstrated the simple dive. He then spent a full minute and a half coaching the first child in line. Everyone watched intently, but the instant she entered the water, the forth child in line turned out the one behind her and said, 'We can do it!' With that the rest of the class dove in, one following the other."

Often when a individual does something wrong, his peer group is punished. One reporter described a boy who was caught writing graffiti on the wall of new school and his entire class had to spend Saturday afternoon cleaning it up.

Japanese Elementary School Organization

Before they learn basic arithmetic or how to read, Japanese first graders are taught how to work together in groups. Classes or 30 to 40 students are typically broken up into smaller groups called “han”, of five or six students each. Tasks are usually assigned to han rather than individuals and han are headed by leaders called “hancho”. In the han system talented students are taught to help students that need assistance and the welfare of the group is given priority over individual achievement.

An emphasis is placed on teaching responsibility and problem solving through team work. Third grade students, for example, are often given a problem on the boards by their teacher. After working for a while to solve it in the han groups, the students are eager to go to the boards and give their answer and explain how they arrived at it. Elementary school students call roll and lead discussions. Various leadership positions are rotated among the students so that every student has a chance to be a hancho, take roll and be the leader of the Play Group, which decides which games and sports students will play and who will be on the teams. Elementary school students are instructed to obey traffic rules and not talk to strangers and told what to to do in the case of an earthquake. School children practice crossing the road in the gymnasium of their schools.

According to a comparative study, Japanese teachers led students for 74 percent of class time, while American teachers led their students for 46 percent. American teachers frequently left children to work alone at their desks, and often divided the class into small groups, according to the children’s levels of skill. Japanese teachers systematically taught the whole class how to underline, outline, organize, and summarize the content of a lesson (Stevenson and Stigler 1992:69, 92, 144). One study of science and social science classes found that Japanese teachers motivate students to learn intrinsically, and to think within their groups (han), while the American teachers rely on reward and punishment as well as providing assistance to individual students (Tsuchida and Lewis 1996:209-210). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

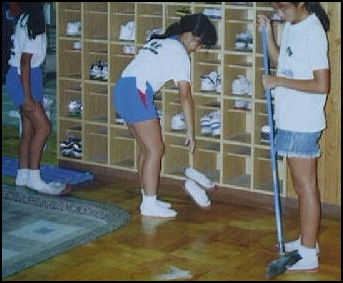

Students are frequently divided into small fixed groups (han) of a certain number of students with mixed-abilities for the social activities of a homeroom class. This group serves as a study group, a laboratory group, and a task team for cleaning, serving school lunch, and performing daily tasks. Students have lunch with their fellow han members in the homeroom classroom. The han members are changed when seating arrangements are changed. The han has one boy and/or one girl leader(s) and group members build solidarity through group activities. ~

All students are responsible for specific tasks, such as being in a committee and/or being the daily monitor for their homeroom class. Peer monitoring is common, and teachers remain largely uninvolved. All students become daily monitors by rotation, and take responsibility for erasing the blackboard, writing a daily journal, and/or being a daily monitor in the morning and afternoon homeroom periods. Moreover, some students are assigned to a committee for one trimester. These committees perform routine tasks such as watering classroom plants, keeping track of items in the lost and found, and distributing handouts. In the afternoon homeroom period, the last period of the school day, the students reflect on what they have accomplished. A daily monitor or a monitor group presides over afternoon homeroom time. The monitor leads a discussion of how everyone had behaved that day, and whether all of the assigned tasks had been completed. ~

Tracking and ability grouping in elementary schools has been a taboo topic in Japan because of the prevailing strong egalitarian principle, though the MOE has created a special study group for advanced students (AS August 18, 2001; AS August 17, 2002). All children are believed to have the potential to develop both their cognitive and non-cognitive abilities through effort and hard work. Tracking stigmatizes slow learners, and ruins their potential by lowered expectations and inferior instruction. The five-point curve grade system was changed into a three-point grade system: “excellent,” “good,” and “fair.” Teachers make efforts to find and encourage the strength of each child. IQ is rarely used as criterion for measuring children’s abilities. ~

Elementary School Curriculum in Japan

The elementary school curriculum covers Japanese, social studies, mathematics, science, music, arts and handicrafts, homemaking and physical education. At this stage, much time and emphasis is given to music, fine arts and physical education. **

Since April 2002, students in third grade and higher spend at least two hours a week on “integrated study” (so-go-tekina gakushu- no jikan). Each school can choose its own topic and design a curriculum for this new subject, which might include international issues, information science, environmental issues, social welfare, and health. The MOE suggests “social experience” education such as debates, volunteer or community activities, surveys, and experiments. Since April 2000, elementary schools have implemented integrated study courses. Fourth-graders at Jo-kon Elementary School used integrated study to investigate how a local river had become polluted. According to a 2003 survey, 89 percent of elementary school students and 78 percent of middle school students enjoyed integrated study classes because it gave them an unconventional academic experience. However, 44 percent of teachers are struggling to find methods of teaching integrated study (AS September 18, 2003). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

English conversation classes are also recommended for comprehensive learning classes in elementary schools. Schools invite an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT), a native English speaker, or a Japanese native who is proficient in English to teach English conversation once every two weeks. In a surprise move, the MOE agreed to cooperate with the juku (cram school) for the first time, and to subsidize English conversation juku for fourth to sixth graders (AS August 30, 1999). The MOE plans to grant 140,000,000 yen for 50,000 elementary school students for English language education on Saturdays in 100 areas nationwide. The MOE will choose five areas in twenty prefectures, recruit 500 fourth to sixth graders in each area, and subsidize their participation in an English conversation juku on Saturdays or Sundays for a total of 35 lessons per year. These juku can be operated by a private individual at home, American schools, cultural centers, English-language schools, and similar institutions. The government pays half of the tuition and the parents pay the remainder (AS August 30, 1999). In 1995, 18 percent of fourth to sixth graders attended English conversational juku (So-mucho- 1996:66). ~

Moral education teaches children ethics and values such as honesty, integrity, respect for the environment, compassion, obedience, and appreciation for their own and other cultures. Moral education is not based on nationalistic ideology, the remnant of the wartime education, as some progressive scholars claim, though it is based on conservative values.6 In this respect it is similar to character and value education in the United States (Ban and Cummings 1999). Patriotism in moral education is very moderate in Japan, compared with the United States and other countries. It is still a taboo to teach students in schools to pledge themselves to their country or to fight for their country. The conservatives, the government, and the MOE have always emphasized the importance of moral education in order to prevent juvenile delinquency. ~

Fifth and sixth graders learn “to appreciate the culture and traditions of their hometowns and this country, in order to understand the efforts of their ancestors, and to develop patriotism for their hometowns and country” and simultaneously to “appreciate the cultures of foreign countries, and make efforts in developing friendship with people in the world as a Japanese citizen” (Monbusho- 1998a). In practice, students develop interpersonal skills and the spirit of volunteerism through reading and discussing stories in supplementary moral education textbooks and/or watching television programs or videos about morality. ~

Elementary School Curriculum and the Prescribed Number of School Hours in the 2002-3 School Year (Grades1 ,2 ,3 ,4 ,5 ,6): A) Japanese Language Arts: 272 ,280 ,235 ,235 ,180 ,175; B) Social Studies: - ,- ,70 ,85 ,90 ,100; C) Mathematics: 114 ,155 ,150 ,150 ,150 ,150; D) Science: - ,- ,70 ,90 ,95 ,95; E) Life Environment Studies: 7 ,102 ,105 ,- ,- ,- ; F) Music: 68 ,70 ,60 ,60 ,50 ,50; G) Arts and Crafts: 68 ,70 ,60 ,60 ,50 ,50; H) Home Economics: - ,- ,- ,- ,60 ,55; I) Physical Education: 90 ,90 ,90 ,90 ,90 ,90; J) Moral Education: 34 ,35 ,35 ,35 ,35 ,35; K) Special Activities: 34 ,35 ,35 ,35 ,35 ,35; L) Comprehensive Leaning Hours: - ,- ,105 ,105 ,110 ,110; M) Total ,782 ,840 ,910 ,945 ,945 ,945. [Source: ~ Monbusho- 1998a, ) Note: One hour-unit has 45 minutes]

Learning Kanji in School

Kumiko Makihara wrote in the New York Times, “The postcard-sized paper my son brought home from school had four imposing Chinese characters written vertically down the middle. It was from a school assignment where the fifth graders each selected a yoji-jukugo, or four-character idiom, that best suited another classmate.Yataro’s friend had chosen “men moku yaku jyo” for him. The first two ideograms mean “honor,” the latter two “vibrant,” and they combine to refer to a person who enthusiastically pursues goals and earns the admiration of others. “You are so lively when playing at recess,” the classmate had written to explain his choice. [Source: Kumiko Makihara, New York Times, March 19, 2010]

“The Japanese use thousands of four-character idioms comprised of Chinese characters that are used in the Japanese written language. When grouped together, the characters create phrases with their own meanings. Familiarity with the expressions is regarded as a sign of being educated, and the idioms frequently appear on school entrance exams. Yataro had to memorize 64 of them for winter break homework. Some were straightforward, like the characters for “different,” “mouth,” “same” and “sound,” which together read “i ku do on,” meaning many people in agreement. Others sparked the imagination, like “south ship north horse,” meaning to travel far and wide. Yataro’s favorite was “han shin han gi” or “half believe half suspect.” It means to be dubious, but Yataro applied his own interpretation and took it to mean one can believe the half that one wants to and dismiss the rest.

“The character clusters reflect the Japanese love of the compact, creative and scholarly. They have a vast historic range. “South ship north horse,” for example, dates back to the early Chinese travelers who forged rivers and canals in the south by ship and conquered mountains and fields in the north on horseback. At the modern end, “den atsu soku tei” was one of last year’s winners of the insurance firm Sumitomo Seimei’s annual create-a-new-yojijyuku-go contest. Den-atsu means voltage, which is pronounced “boltage” here; soku means speedy, and tei means imperial. The result is a reference to the world’s fastest sprinter: Usain Bolt.

“On the back of the paper my son brought home from school, the teacher requested that the parents write an idiom that befits their child. To broaden my choices, I went to the bookstore where I found a shelf full of titles like “Yoji-jukugo and Sayings You Can Use in Conversation and Speeches.” I settled on the 1000-entry “Yoji-jukugo Dictionary to Bolster Your Brain.” Figuring this was a lesson in positive reinforcement as much as learning another phrase, I excluded the negative ones no matter how well they described Yataro. Out went “horse ear east wind” — the eastern wind is a spring breeze, pleasant to humans but meaningless to horses: a perfect depiction of Yataro turning a deaf ear to my pearls of wisdom. I also had to avoid the praiseful ones lest the teacher think I was an indulging parent. So I passed on “large vessel late achievement,” which describes someone who triumphs in maturity, even though I have my hopes pinned on the chance that my son is a late bloomer.

Yataro begged me not to bring to the assignment my personal gripes against the teacher, who I feel is petty in his criticisms of the children. Along that line my choice had been “ka gyu kaku jyo,” or “Snail tentacles on top of,” which expresses small-scale squabbling through the image of the two tentacles fighting each other. When I finally sat down to write, I wrote my choice for him: “jyuku doku gan mi,” “thorough reading enjoy taste,” which means to read deeply. “Reading lets you glimpse into other worlds,” I wrote to Yataro who loves to lie down with a book...And then I could not resist. In the corner I drew a small picture of a snail and put boxing gloves on each of the tentacles.

International-Understanding Education in Ume Elementary School

Ume Elementary School in Marugame was designated as an Associated School for Research on the Education of Foreign Students for the 1998-9 and 1999-2000 school years.2 The school of 700 students has had foreign students since 1994, and in 1999 the school had six students from Peru, one student from Brazil, and one student from China.3 This school sponsors more programs and events for international-understanding education than other schools because it has both foreign students and the state funding for international-understanding programs. ~

In 1997, the school converted an unused room into an international exchange room, called “Amigo & Amiga.” This room is a small museum of the world, with pictures, clothes, stamps, books, money, toys, and musical instruments, in addition to a small library. It has a large section on Peru because the school has had Peruvian students since 1994. This room is open to all students who are interested in learning about other countries, and is also used for the annual World Orientation event. ~

For World Orientation, all students assemble in the international exchange room and form groups. Each group is assigned a set of questions about the world, and competes with other groups by solving the questions together. The monthly school newsletter, Buenos Tardes, is devoted to foreign students and their countries, and provides general information about the world. One teacher, who had taught at a Japanese daily school in Thailand for three years, writes articles about Thailand. This school paper is read not only by the students, but also by their parents, who learn about their children’s classmates from other countries. ~

In the 1998-9 school year, the school hosted several special events for international understanding, and provided many opportunities for foreign students to talk about their homelands. First graders learned greetings in different languages, including Spanish from one of the Peruvian students. Second graders listened to a guest speaker’s talk about his life and experiences in Brazil. Third graders learned children’s songs from all over the world, including an Andean folksong and a Peruvian folkdance. Fourth graders played with Peruvian toys, and taught first graders how to play with these toys. Fifth graders learned how to cook Peruvian foods from the mother of one of the Peruvian students. A British teacher, the Coordinator for International Relations (CIR), was invited to talk about England, and played a game with the sixth graders. ~

One teacher brought notebooks that the students had made or donated to elementary school students in Nepal, and showed a video of Nepalese students using these notebooks. In 1998, students collected 72 pairs of shoes, 36 balls of yarn, and 316 telephone cards to be sent to children in Nepal. ~

Special Education and Volunteers in Japanese Elementary Schools

In the near future, the MOE plans to implement special education for learning disabled children, modeled on special education for LD children in the United States. Currently, special classes for children with mild disabilities (sho-gaiji gakkyu-) are held in regular elementary schools. Severely disabled children attend separate special schools for children with visual impairments (mo-gakko-), children with hearing impairments (ro-gakko-), and children with orthopedic disabilities, mental retardation, and sickly children (yo-go- gakko-). [Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~]

Responding to the problems of an aging society, school-initiated volunteer activities have become a popular type of social experience education and human rights education, with the goal of showing children the importance of compassion for the elderly and the disabled. Many schools carry out visitations to the elderly in nursing homes and to the disabled in special schools or homes for the disabled through integrated study classes and human rights education programs. Schools arrange for their students to do volunteer work, in cooperation with local social welfare agencies and the volunteer centers, and design volunteer programs for the elderly and the disabled, as well as for cleaning, recycling, and raising donations for the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). ~

Students visit the elderly living alone and in nursing homes, and participate in social activities with senior citizens’ clubs. The students learn to care for and be considerate to the elderly, to appreciate their lives, and to see things from their perspective. In order to have teachers volunteer with the elderly and disabled, since 1998, a week of practical training in special schools, or care in social welfare facilities has been a requirement for teaching certificates for elementary and middle school teachers. However, voluntarism has not yet become as popular in Japan, as it is in United States. Despite the recent school sponsorship in volunteer activities, only 23 percent of children join participate in volunteer activities, according to a 1999 survey of fifth- and eighth-graders in Tokyo (Kodomo no 2000). ~

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Source: Miki Y. Ishikida, Japanese Education in the 21st Century, usjp.org/jpeducation_en/jp ; iUniverse, June 2005 ~; Education in Japan website educationinjapan.wordpress.com ; Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), Daily Yomiuri, Jiji Press, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated Japan 2014