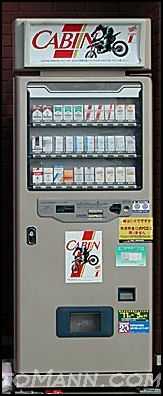

TAXES IN JAPAN

cigarettes supply

a healthy chunk of

government funds Japan's tax revenues for fiscal 2010-2011 rose 7.1 percent from the previous year to 41.49 trillion yen ($513 billion), Kyodo reported, exceeding the earlier forecast 39.64 trillion yen, mainly supported by improving corporate earnings, the Finance Ministry. Higher corporate tax revenues thanks to an improving business environment as well as a rise in individual income tax receipts helped overall tax revenues top 40 trillion yen for the first time in two years.Tax revenues were up 5.2 percent in 2007 to ¥4.86 trillion with ¥2.58 trillion coming from income taxes, ¥1.19 trillion from consumption taxes, ¥521.2 billion from corporate taxes, [Source: Kyodo, July 2, 2011]

Japan has the most progressive tax system in the world. The top bracket is 65 percent. Inheritance taxes can be as high as 75 percent of the value of the property and claim up to 70 percent of inherited wealth. The corporate tax in Japan stands at 40 percent, the highest in the developed world. In South Korea the corporate tax rate is only 24 percent.

There is a five percent consumption (sales) tax. There has been some discussion of raising the consumption tax to cover pensions in the future. The only problem is that when this was done in the past consumers spent less and Japan went into a recession.

Japan’s retirees are eating up more tax money all the time. Payroll tax rates needed to cover retirees in 1995 was 24.3 percent. Projected payroll tax rates needed to cover retirees in 2030 is 53.2 percent.

There is tax evasion in Japan as there is everywhere. In March, 2008, ¥5.93 billion ($57 million) in cash was found in the Osaka home of two sisters who inherited a lucrative real estate firm from their father. There was so much money it took more than 24 hours for counting machines to count it all. Most of the money had been withdrawn from bank accounts held by their father before his death in 2004 presumably to avoid paying taxes on it. The two sisters were arrested for tax evasion for not declaring $57 million of a total of $72.56 million they inherited. Most of the money was stored in cardboard boxes kept on sister’s garage.

A daily door-to-door tax collection system that was introduced in 1875 endured until 2009 on Miyajima island near Hiroshima.

A report by the Board of Audit said that ¥1.70 trillion worth of taxpayers money was wasted in fiscal 2009. Over ¥18 billion alone in tax money was used to bail out financially-troubled government hotels.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Social Security in Japan mofa.go.jp/j_info ; Reforming Social Security in Japan ier.hit-u.ac.jp/pie ; Wikipedia article on Social Welfare in Japan Wikipedia ; Taxes in Japan www2.gol.com/users ; Income Taxes and Tax Laws worldwide-tax.com ; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare mhlw.go.jp/english ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Social Security Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp National Institute of Population and Social Security Research ipss.go.jp

Links in this Website: GOVERNMENT AND SYMBOLS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PRIME MINISTER AND PARLIAMENT Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POLITICS AND ELECTIONS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POLITICIANS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUREAUCRACY IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CORRUPTION AND GOVERNMENT SCANDALS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TAXES, WELFARE AND SOCIAL SECURITY IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Good Government Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on the Government of Japan Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the Japanese Flag Wikipedia ; Government Organization Chart kantei.go.jp and kantei.go.jp/foreign/link/chart ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Government Chapter stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp Governments on the WWW — Japan Linksgksoft.com ; Japan Echo, a Journal on Japanese Politics and Society japanecho.com ; Electronic Journal of Japanese Studies japanesestudies.org

Prime Minister, Legislature and Leaders: CIA List of Current World Leaders /www.cia.gov/library ; Kantei, Office of the Prime Minister kantei.go.jp ; Cabinet Office cao.go.jp ; House of Representatives (Shugiin) shugiin.go.jp ; House of Councillors (Sangiin) sangiin.go.jp/ ; National Diet Library ndl.go.jp/en National Diet Building in Tokyo Photos of National Diet Building at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Japan Visitor Japan Visitor ; Japanese Lifestyle japaneselifestyle.com.au Constitution Constitution of Japan solon.org/Constitutions/Japan ; Birth of the Constitution of Japan ndl.go.jp/constitution ; Research Commission on the Constitution shugiin.go.jp ;

Taxes on Alcohol, Cigarettes and Gasoline in Japan

alcohol also supplies a healthy

chunk of government funds Taxes on alcohol account for 4 percent of national tax revenues. Of this beer generates the largest share.

The tobacco industry earns the Japanese government $19 billion a year in taxes, almost 3 percent of the government's total revenues. Japan Tobacco, Japan’s largest cigarette maker, is 67 percent government owned and was a government monopoly until it was privatized in 1985. Many JT executives are former government bureaucrats. Much of the tax money that the government earns from cigarettes comes from JT cigarettes.

In March 2008 there was a big fight between the LDP and the opposition in the Diet over the provisional gasoline tax — whose revenues had been used for road building projects — on the issue of whether the tax was necessary and whether or not funds from the tax could be used for other things than building roads. For a week the tax was dropped after it was rejected by the opposition-controlled upper house. During that time drivers filled up their tanks while prices as much as ¥25 per liter lower than usual. The loss of revenues however was devastating to local governments who rely on that money to maintain roads and other projects.

U.S. Displaces Japan in 2012 as Having the World’s Highest Corporate Taxes

In 2012 Japan's corporate tax rate dropped to 38 percent while the combined U.S. corporate tax rate rose to 39.2 percent, making it the highest in the developed world. In March 2012, Patrick Temple-West and Kim Dixon of Reuters wrote: The United States will hold the dubious distinction starting on Sunday of having the developed world's highest corporate tax rate after Japan's drops to 38.01 percent, setting the stage for much political posturing but probably little tax reform. Japan and the United States have been tied for the top combined, statutory corporate rate, with levies of 39.5 percent and 39.2 percent, respectively. These rates include central government, regional and local taxes. [Source: Patrick Temple-West and Kim Dixon, Reuters, March 30, 2012]

Japan's reduction , prompted by years of pressure from Japanese politicians hoping to spur economic growth, will give that country the world's second-highest rate. The average 2012 corporate tax rate for the 34 developed countries is 25.4 percent, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Japan’s Consumption Tax

The bills to raise the 5 percent tax rate to 8 percent in April 2014 and to 10 percent in October 2015 were passed into law by the House of Councillors in August 2012. Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times, Noda’s plan to double Japan’s sales tax was approved by Parliament after months of haggling, but only after Mr. Noda promised opposition lawmakers that he would call early elections — a move that is likely to end his term in office and his party’s hold on power. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, August 10, 2012]

Despite low popularity ratings, Mr. Noda has pushed ahead with the plan to raise the tax to 10 percent from 5 percent by 2015, an increase he says is necessary to start reducing the country’s debt. Mr. Noda and other deficit hawks worry that Japan’s debt, which is the largest among industrialized nations, will set off a crisis akin to Europe’s. Moreover, Japan’s social security spending is surging as its population ages, adding about $13 billion to government expenditures every year.

“To ask the public to bear a bigger burden is a painful topic that every politician would like to avoid, run away from, or delay until after his term in office,” Mr. Noda said. “But somebody must bear the burden of our social security costs.” The prime minister’s critics say that his fears are overblown — interest rates are still at rock-bottom levels on Japanese government bonds — and that raising taxes will only weaken Japan’s fragile economy. Some of Mr. Noda’s toughest opposition has come from within his own Democratic Party. Last month, 50 lawmakers opposed to the tax plan left the party, greatly weakening it. The main opposition Liberal Democratic Party had also criticized Mr. Noda’s tax plan but this week agreed to back it in exchange for a vague promise from the prime minister that he would call elections “soon.”

Economists point out that Mr. Noda’s plan would fall far short of erasing Japan’s debt. Moreover, despite Mr. Noda’s claims that the consumption tax is devised to reduce the burden on future generations, the bulk of the new tax revenues would be put toward paying for the surging medical bills and pensions of the elderly. Mr. Noda had promised to reform the social welfare system to address concerns that younger Japanese are bearing a disproportionate burden as they support the country’s pensioners. But action on that part of the plan has been delayed amid squabbling by policy makers.

Consumption Tax of 10 percent Considered Too Low

Hideo Kamata wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The government's goal of turning the primary budget balance into a surplus by fiscal 2020 is unlikely to be achieved. Even when the bills to raise the consumption tax rate complete their journey through the Diet, the extra revenue accrued will fall short of the funds needed to reconstruct the nation's finances. Further tax hikes will be inevitable to cover ballooning social security expenses. [Source: Hideo Kamata, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 28, 2012]

“According to the International Monetary Fund, Japan's debt-to-GDP ratio was about 230 percent in 2011, the worst among developed countries and much greater that the 161 percent chalked up by Greece. In addition, Japan's social security burden is increasing annually as the population grays.

“Raising the consumption tax rate to 10 percent will improve this grave financial situation up to a point. The government plans to make hefty budgetary allocations in such fields as the environment, medical services and disaster prevention. However, it would be counterproductive to fiscal reconstruction if the government recklessly pours money into projects

102 Trillion Yen Requested for Fiscal 2013 Budget

In September 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Budget requests from government agencies and ministries for fiscal 2013 totaled 102.48 trillion yen ($1.3 trillion) , according to the Finance Ministry. General account budget requests came to 98 trillion yen, while 4.48 trillion yen was requested under the special account for reconstruction following the March 11 disaster and the nuclear crisis at Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. The total requested amount ballooned as no limit had been set on funds requests related to reconstruction. Additionally, planned debt-servicing costs increased by about 2 trillion yen from fiscal 2012 to 24.65 trillion yen. [Source: Jiji Press, September 14, 2012]

Excluding reconstruction-related spending, fiscal 2013 budget requests hit 97.1 trillion yen, an increase of about 2 trillion yen from fiscal 2012. About 2.1 trillion yen was requested for areas prioritized under the government's national revitalization project. Of that figure, 443.8 billion yen was sought for energy and the environment, 119.6 billion yen for health promotion and 133 billion yen for agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

The Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry sought a total of 639.1 billion yen, the most among all ministries and agencies. General account budget requests, excluding debt-servicing costs, came to 73.36 trillion yen, up by nearly 1 trillion yen from fiscal 2012, due chiefly to an 840 billion yen natural increase in social security costs. To promote fiscal reconstruction, the government plans to curb general account outlays, excluding debt-servicing costs, to 71 trillion yen or below.

Gap Between Government Expenditures and Tax Revenues

In December 2012, The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Japan's fiscal condition is at a critical stage. Tax revenue has been declining since the 1990s due to an economic slowdown after the "bubble economy" burst. On the other hand, governmental expenses have been increasing due to a rise in social security costs covering the rapidly graying society and economic stimulation measures. The gap between tax revenues and government spending has rapidly expanded, resembling the gaping mouth of an alligator when seen on a graph. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 5, 2012]

To fill the gap, each year a rising number of government bonds have been issued, contributing to the nation's debt. The fiscal 2012 general account budget's spending was set at about 90 trillion yen, nearly half of which was financed through such bonds. The amount of government bonds issued to cover the initial budget has surpassed tax revenue for three consecutive years through fiscal 2012. Additionally, social security expenditures in the fiscal 2012 budget amounted to 26.39 trillion yen. These costs are expected to continue to increase annually by 1 trillion yen because of the nation's aging society.

Under these circumstances, integrated reform of the social security and tax systems, with an increase in the consumption tax rate as its pillar, is now being promoted. The reform is designed to stabilize the fiscal foundation of the social security system. It is also meant to transform the current structure, which emphasizes support for the elderly, into an "all-generation" system by improving support measures for families rearing children, for instance.

The consumption tax rate will be raised in two stages — to 8 percent in April 2014 and to 10 percent in October 2015 — according to laws on the integrated reform of the social security and tax systems, enacted in April 2012 with support from the Democratic Party of Japan, the LDP and Komeito. However, some observers believe even a 10 percent consumption tax cannot sufficiently finance the nation's social security programs. To reach the government's goal of "achieving a surplus in the primary fiscal balance in fiscal 2020," a further six point increase of the tax rate is necessary, some experts say.

Currently, gaps exist among different generations regarding the benefits they will receive during their lifetime, such as pension payments, and the financial burdens, such as taxes and social security insurance premiums, they will have to bear. According to the Cabinet Office's annual economic and fiscal report for fiscal 2005, those aged 60 and older as of 2003 would receive benefits exceeding the amounts they paid in by about 49 million yen during their lifetime. However, the financial burdens of those in their 20s as of 2003 would exceed eventual benefits by about 17 million yen.

With the birthrate remaining below replacement level and society aging at an increasing pace, such generational gaps over social security programs raise serious concerns. The new administration must aim to reform the social security system to transform it into one that can maintain a fair balance among all generations.

Welfare in Japan

The Japanese government provides medical insurance, pension benefits, unemployment benefits, child allowances, welfare services, and workers accident compensation. Laid off workers receive about $360 a month.

1) Institutions for public aid recipients: 299; 2) Welfare institutions for the elderly: 8,431; 3) Facilities for the rehabilitation and support of the physically handicapped: 715; 4) Women’s protective facilities: 48; 5) Children’s welfare institutions: 32,353; 6) Institutions for the support of the mentally handicapped: 2,567; 7) Welfare facilities for women and children: 62; 8) Rehabilitation facilities for the mentally handicapped: 635; 9) Other social welfare institutions: 8,717: [ Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, As of October 2009]

In 2009, the Hatoyama government proposed abolishing gas taxes and replacing them with a green tax that would be used combat global warning and cover the revenues lost by abolishing the gasoline tax. In the end a new tax system was put in place that suspended taxes when the price of gasoline rose above ¥167 a liter and resumed it when the price was below ¥126 a liter with a special tax when it is in between.

Japan never built up a large welfare of safety net. Companies traditionally took care of their employees and nearly everyone worked for a company. In Japan today, there is movement to implement more user-cost schemes in the welfare system.

Koizumi led a campaign to cut government spending in many sectors, with the welfare being a primary target. During his years in office state pensions were cut and health insurance premiums were raised. Welfare payments in Tokyo were slashed from $826 a month to $625 in the mid 2000s.

In Japan, welfare has traditionally been provided by the state, private companies and families themselves rather than from charities and NGOs. An increased role for such groups started to emerge after the 1885 Kobe earthquake.

People on Welfare in Japan

In June 2012, the number of people receiving welfare benefits topped 2.1 million for the first time as of the end of March, the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry announced. The preliminary report figure was up 10,695 from February to 2,108,096, rising for the ninth straight month since July last year, when a 60-year record high was posted.The number of households receiving livelihood protection benefits under the Public Assistance Law also reached a record of 1,528,381, up 6,897 from the previous month. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 14, 2012]

“While 40 percent of welfare recipient households were elderly, "other households," which includes unemployed people seeking work, accounted for 17 percent, or 260,945 cases. Recipient households are classified into six categories, including single-mother households and single-father households.

“Welfare benefits are expected to top 3.7 trillion yen in fiscal year 2012-2013, up about 1 trillion yen over the past five years.As the numbers continue to rise, there has been concern about recipients receiving benefits despite having family members or relatives in a position to support them. To address this problem, the ministry is considering reforms to the public assistance system, including such measures as confirming whether an applicant's family members can financially help the applicant, and helping recipients who are able to work find jobs, according to the ministry.

The percentage of households with no savings hit 22.8 percent in 2006, the highest since surveys on this subject were kept in 1953.

More than 40 percent of those receiving welfare are elderly. A large number of young people are also poor. According to the OECD 1 in 7 Japanese kids under 17 lives in poverty. Many are children of parents who are unemployed, don’t have steady work or are temporary employees.

Welfare for Older People in Japan

With advances in medical technology and improvements in public health and nutrition, the average life span of the Japanese people has markedly increased. As the elderly population expands, the number of bedridden and senile persons who require care is growing rapidly. By 2055 elderly people will account for 40.5 percent of the population in Japan, which means that one in 2.5 people will be 65 years or older. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The number of older Japanese requiring care will also rise as a result. Aggravating society’s care problem is the fact that the average family’s ability to provide such care is decreasing, partly because of the ongoing transition from extended to nuclear family patterns. In response to these circumstances, the government is reorganizing the welfare system for the elderly together with medical services for those elderly requiring care. As part of this reorganization, in 2000 a long-term care insurance system was inaugurated as a new social insurance system. Welfare measures for the benefit of elderly persons are carried out on the basis of the Social Welfare Service Law for the Elderly (Rojin Fukushi Ho), enacted in 1963. Provisions of the Health and Medical Service Law for the Elderly (Rojin Hoken Ho), enacted in 1982 are also relevant to maintaining and protecting elderly persons’ physical and mental health.

“Welfare measures for the benefit of elderly persons, together with those which benefit children and handicapped persons, are administered by local-governments, welfare offices (“fukushi jimusho”) in particular. To provide relevant assistance and advice, these offices employ certified social workers (“shakai fukushi shuji”) with specialized knowledge and skills. Working in collaboration are commissioned welfare volunteers (“minsei iin”), who try to gain an accurate understanding of the situation of elderly persons in their geographical areas and who assist the local welfare offices with their work.

“Welfare facilities for elderly persons needing special care include day service centers, nursing homes for the elderly (“kaigo rojin hoken shisetsu”), special nursing homes for the elderly (“tokubetsu yogo rojin homu”), and group homes for elderly with dementia (“chihosei koreisha gurupu homu”). To cope with the aging of society in the 21st century, the Japanese government instituted the Ten-Year Strategy to Promote Health Care and Welfare for the Elderly (commonly known as the Gold Plan) in 1989. This plan was revised in 1994 under the name New Gold Plan. The New Gold Plan made various improvements by fiscal 1999, including an increase in the number of home helpers for elderly persons, improvements in the capacity of short-stay facilities to accept them for periods of rest and special care, the offering of day services (including meals and physical exercise) at day service centers, and an expansion of at-home services such as visits by doctors and nurses who provide special care and guidance in physical exercises for regaining impaired functions.

“Three bills to create a long-term care insurance system for the elderly were approved in the Diet in December 1997, and the new system became effective in April 2000. Since then the use of most of the above-mentioned facilities and services has been provided via the long-term care insurance system. Another new plan, known as Gold Plan 21, was launched in 2000. The specific measures envisioned by this plan are: (1) improving the foundation of long-term care services, (2) promoting support measures for the senile elderly, (3) promoting measures to revitalize the elderly, (4) developing a support system in communities, (5) developing long-term care services which protect and are trusted by users, and (6) establishing a social foundation supporting the health and welfare of the elderly.

Aging Poverty in Japan

There is a growing number of poor seniors in Japan. Between 1995 and 2005 the number of indigent elderly increased 183 percent to around a half million people, many of whom have effectively been abandoned their children. Many people in the field say the half million figure is a gross underestimate and the real figure is around five times higher.

Housing complexes for the poor are often filled with elderly people. Almost half of all welfare beneficiaries are 65 or older. By contrast in the United States one in 10 are. Some receive nothing because they homeless and the government requires them to have a fixed address to get assistance. Others are too embarrassed or ashamed to apply for it.

The elderly have been hurt by welfare cuts. Some get by on rice and noodles, keep the heat off even in mid winter to save energy costs. and have given up going to weddings and funeral because they can’t bear the shame of not being able to offer a present. See Welfare,

Children’s Welfare in Japan

The first basic law related to children and their welfare was the Child Welfare Law (Jido Fukushi Ho), enacted in 1947. According to this law, “children” (“jido”) are defined as young persons under the age of 18. There are three sub-categories: infants of less than one year of age, who are officially called “nurslings” (“nyuji”); children aged one year or more who have not yet entered elementary school, known as yoji; and children from elementaryschool age through the age of 17, who are called “shonen”. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In accordance with the Child Welfare Law, each of Japan’s 47 prefectures operates several child guidance centers (“jido sodanjo”). Each of these centers employs child welfare workers (“jido fukushishi”) who have received specialized training and are available for consultation on all sorts of matters concerning children in the areas under each center’s jurisdiction. They make systematic inquiries and decisions from a specialist’s viewpoint, give necessary guidance to children’s guardians, and authorize arrangements for the temporary custody of children by foster parents or for the entry of disadvantaged children into residential welfare facilities.

“Such arrangements are made in close consultation with welfare offices and health centers (“hokenjo”). City, town, and village governments employ commissioned child welfare volunteers (“jido iin”) who, in cooperation with the child welfare workers and certified social workers, try to gain an adequate understanding of the living environment of children, pregnant women, and new mothers who need assistance. Public facilities for the special care of children include homes for infants (“nyujiin”), day nurseries (“hoikusho”), and hospital homes for children with severe mental and physical disabilities.

Revisions of the Child Welfare Law in Japan

The Child Welfare Law underwent large-scale revisions in 1997. These were made in order to respond to changes in the living environment of children during the last 50 years. Examples of such changes are the now predominant pattern whereby both husbands and wives work to maintain the family income; the trend toward nuclear families with no more than two generations per household; and the decrease in the number of children, with a total fertility rate (average number of children estimated to be persons born to each woman during her lifetime) of only 1.37 in 2009. The revisions in the Child Welfare Law emphasize going beyond the concepts of protection and emergency relief to address the issue of supporting children in ways that will help them become socially, spiritually, and economically self-reliant by the time they are young adults. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The revised law provides for the establishment of support centers for households with children (“jido katei shien senta”), which work with the child guidance centers and give many types of advice and guidance for children in their area. The names and functions of some types of facilities have been changed to emphasize “self-reliance” (“jiritsu”) rather than just custodial care. For example, the former “homes for training and education of juvenile delinquents” (“kyogoin”) have been renamed “children’s self-reliance support facilities” (“jido jiritsu shien shisetsu”), and “homes for fatherless families” (“boshiryo”) have been renamed “livelihood support facilities for mothers and children” (“boshi seikatsu shien shisetsu”). For single-mother households, necessary measures, along with those already in place under the Child Welfare Law, were facilitated by the Law for the Welfare of Fatherless Families and of Widows (Boshi Oyobi Kafu Fukushi Ho), enacted in 1964.

“Prior to the revision of the Child Welfare Law, a 10-year agenda, officially named Basic Orientations to Assist Child-Raising and colloquially known as the Angel Plan, was jointly put together in 1995 by the Education, Health and Welfare, Labor, and Construction ministries. Since one of the reasons for the trend toward smaller families is the growing presence of women in the workplace, this plan aims to build an environment that makes it possible for women to feel confident that they can raise children while holding jobs. Among the various measures promoted were the expansion of the capacity of day nurseries, a lengthening of the hours during which day nurseries are open, and a large increase in the number of child-rearing support centers (“kosodate shien senta”) throughout Japan.

“The Angel Plan was revised in 1999 to create the New Angel Plan, which expanded numerical targets for various types of care facilities. In 2003 the Law for Measures to Support the Development of the Next Generation (Jisedai Ikusei Shien Taisaku Suishin Ho) was passed. Covering the 10- year period beginning 2005, this law prescribes guidelines for formulating action plans by the national government, local governments, and business operators to develop the environment necessary to bring up healthy children. The prevention of child abuse has become an increasingly prominent issue, with the number of reported cases growing rapidly in the past decade.

“The Child Abuse Prevention Law went into effect in 2000 and was revised in 2004. This revision expanded the criteria under which people are obligated to make a report to a child guidance center, and it clarified the authority of center personnel to make on-site investigations.

Welfare for Disabled Persons in Japan

Public welfare measures for handicapped persons are carried out on the basis of the Law for the Welfare of Physically Disabled Persons (Shintai Shogaisha Fukushi Ho), enacted in 1949; the Law for the Welfare of Mentally Handicapped Persons (Chiteki Shogaisha Fukushi Ho), enacted in 1960; and the Law concerning Basic Policies for the Handicapped (Shogaisha Kihon Ho), enacted in 1970. These laws apply to measures for people of age 18 and over since handicapped persons under the age of 18 are covered by provisions of the Child Welfare Law. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Welfare measures for physically handicapped persons are administered by local governments, particularly through welfare offices and rehabilitation consultation centers for physically disabled (“shintai shogaisha kosei sodanjo”). At these offices and centers, persons with specialized knowledge and skills consult with physically handicapped persons. They are assisted in their work by commissioned welfare volunteers (“minsei iin”) and consultants for physically disabled persons (“shintai shogaisha sodan’in”), appointed by city, town, and village governments.

Persons designated as physically handicapped are entitled to various public welfare services, including consultation and guidance, special rehabilitation and medical services, the replacement or repair of auxiliary equipment and devices, and accommodation in various types of rehabilitation facilities. For those who are seriously disabled, services may include grants or loans of bathtubs, chamber pots, specially designed beds, and word processors, as well as the dispatch of home helpers and medical personnel for at-home examinations.

“To help disabled persons to be self-reliant in society, central and local governments provide economic assistance by purchasing items which they manufacture, and various types of activities have been devised to respond to disabled persons’ needs in ways that facilitate their participation in society. Allowances for people with special disabilities (“tokubetsu shogaisha teate”) are provided to help disabled persons be economically self reliant, and there are special pensions through a system of support and mutual help for people with mental and physical disabilities.

“In the case of physically or mentally handicapped children, special child-rearing allowances (“tokubetsu jido fuyo teate”) are provided to legal guardians who raise these children at home. Allowances are rated according to the extent of the disabilities. Educational facilities include schools for blind persons, schools for deaf persons, residential schools where special care is provided, and special classes within public schools. In recent years it has become more common for handicapped children to receive education together with normal children in ordinary schools. Emphasis is also given to measures aimed at preventing the development of handicaps. For example, in keeping with the provisions of the Maternal and Child Health Law (Boshi Hoken Ho), enacted in 1965, health examinations and guidance are provided to pregnant women.

“In Japan, as in other countries, the concept of “normalization” has received increasing attention in recent years. The aim of normalization is to create a barrier-free society where handicapped persons can be self-reliant and engage freely in social activities in their local communities. Addressing this task, in December 1995 the Japanese government put together the Government Action Plan for Persons with Disabilities: Seven-Year Normalization Strategy. Under this plan an effort was made to promote the independence of persons with disabilities and help them to live in communities as ordinary citizens. A new plan launched in 2003 continues this focus and expands the numerical targets for home helpers, day service centers, group homes, etc.

Welfare for People with Economic Difficulties in Japan

Daily-life welfare support for people with economic difficulties is provided on the basis of the Public Assistance Law (Seikatsu Hogo Ho), enacted in 1950. The fundamental principle of this law is to guarantee a minimum livelihood for people who are living in poverty because of circumstances beyond their control, with the aim of helping them achieve self-reliance. This support is initiated on the basis of applications made by the person who needs the assistance or by that person’s legal guardian or a relative living at the same address. In principle, the assistance is provided to the household unit. This daily-life support is administered by welfare offices, under the responsibility of certified social workers. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“As in the case of welfare activities involving children and handicapped and aged persons, they are assisted in their work by commissioned welfare volunteers appointed by local governments. The types of support fall into eight categories as follows: (1) assistance for food, clothing, and other items needed to meet daily-life requirements; (2) assistance for education, including the costs incurred for compulsory education (textbooks, school meals, class fees, etc.); (3) assistance for housing; (4) assistance for medical examinations and medicine; (5) assistance for childbirth; (6) assistance with funds and equipment needed for work purposes; (7) assistance for funeral expenses; and (8) assistance for long-term care.

Welfare Cheats in Japan

In November 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: A man in his 50s living in the suburbs of Tokyo makes his living as a health food wholesaler, using a car he borrows from a friend. But he conceals his income from the government, so he can receive welfare payments. "I know it's against the law, but I want to save some money," he said. To make sure the government does not find out about his earnings, he deals in cash and does not provide receipts. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 21, 2011]

Cases of people receiving welfare benefits illegally are increasing as more people underreport or do not report their incomes. According to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, 19,726 cases of illegal welfare payments totaling about 10.2 billion yen were discovered during fiscal 2009, about double the 9,264 cases amounting to 5.8 billion yen recorded in fiscal 2003.

About 60 percent, or 11,874, of the cases were payments received by people underreporting or failing to report earnings. Twenty percent, or 4,022, were cases of not declaring pension incomes. There were also 1,225 payments received by those not declaring insurance income or savings. The ministry said the increase in uncovering fraud was due to more thorough checks of welfare payments against information on withholding and other taxes. A senior police official said the real number of fraud cases is probably higher as there are cases involving gangsters.

Sophia University Prof. Ichisaburo Tochimoto said rampant illegal welfare payments can lead to prejudice against truly needy people and an increased sense of distrust in the public system. "The government should strengthen fraud-prevention measures and build a system where illegal payments are not permitted," he said.

Welfare Scams Involving Gangster in Japan

In 2007, according to a Yomiuri Shimbun report, a former gangster was arrested in Takikawa, Hokkaido, for conspiring with a taxi service to pad fares for trips to a hospital about 100 kilometers away in Sapporo. Along with his wife, the man, 46, who has already been convicted, is believed to have received up to 130 million yen in benefits per year, accounting for about 10 percent of the municipality's welfare budget. The two are believed to have received more than 200 million yen in total in the fraud, and some of the money is said to have gone to the man's criminal organization. The city government was unaware of the fraud for more than a year after the payments started.

A former senior official of the Hokkaido prefectural police who was in charge of the case said the amount was absurdly high, and the city should have discovered it sooner. "Several gangsters told me it is very easy to get money from government offices. They said, 'All we need to do is bang on the desk and intimidate them,'" he said.

There are many similar incidents, including a case in July, in which a gangster was arrested in Adachi Ward, Tokyo, for illegally receiving 11 million yen in welfare payments. Alarmed by these cases, the ministry notified municipal offices to contact police if they received dubious welfare applications and to refrain from paying benefits in principle when applications were filed by gangsters.

But the ministry only cited the "attitude when applying" or " living conditions" as benchmarks to decide whether police should check applications. An official in charge of welfare in Aichi Prefecture said it was hard to weed out gang members since no one overtly acts like a gangster when applying.

A recent court decision stunned municipal governments regarding police checks. The Miyazaki District Court on Oct. 3 ordered the Miyazaki municipal government to withdraw its rejection of a welfare application filed by a 60-year-old man. The city rejected the application because the Miyazaki prefectural police identified the man as a member of an organized crime group affiliated with the Yamaguchi-gumi crime syndicate. The court ruling said the decision on whether to pay the benefits should be made without relying solely on police information.

The city was apparently bewildered by the decision, questioning how it could check the man's background without an investigation as it has no authority to conduct criminal investigations. The city said it could not prevent illegal activities if it was unable to use police information. Others in the national and local governments are also questioning the ruling, and there is a great deal of anticipation surrounding an appeal court's ruling on the case.

Government Promotes Self-Reliance

In September 2012, Tomoko Koizumi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “A new aid package for people in need compiled by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry will include comprehensive measures to help public assistance recipients and those who have been unemployed for a long period of time become more self-reliant. The move was prompted by criticism that more extensive aid should be provided to those in need before designating them as public assistance recipients in an effort to prevent spending on benefits, which has stressed the government's finances, from ballooning. [Source: Tomoko Koizumi / Yomiuri Shimbun, August 18, 2012]

The ministry established a special subpanel to the Social Security Council in April to discuss reforms on the public assistance system. At the subpanel's meetings, the prevailing view was that the problems facing the needy were not limited to monetary concerns, but also included a number of issues such as domestic circumstances and education. This opinion led to the proposed creation of a system in which the central and local governments would collaborate with private-sector entities.

After examining systems used in other countries, the ministry decided to model the reforms after France's system, which encourages the needy to become self-reliant, instead of Germany's, which penalizes people who do not participate in employment aid. Welfare recipients are categorized as elderly, disabled, single parents or "other." The number of "other" has been rapidly increasing. Such people may fall into a vicious cycle of relying on public assistance for an extended period of time, which will cause them to lose motivation and make it difficult to become self-reliant. Government spending for such benefits has skyrocketed by 1 trillion yen over the past five years. "Even if implementing the planned measures temporarily increases costs, it can help save social security spending in the long term," a senior ministry official said.

One aspect of the reforms that has attracted attention is a system devised to prepare people who have not held a job for an extended period of time for potential jobs by enforcing orderly lifestyles, such as encouraging a habit of going to bed and waking up early. Although there is already a job-training plan in place for unemployed people, many have been unable to participate in training sessions due to poor habits and lifestyle choices.

The ministry will also consider employing the needy and public assistance recipients in "intermediate jobs." This would provide them with an opportunity to engage in light work, such as easy farm labor, before transitioning to regular jobs. Under the initiative, the ministry aims to establish comprehensive assistance centers, which will provide customized aid plans to the needy and help them reach their goals. The centers will be operated by nonprofit organizations.

Another major change is that local governments will directly pay rent to landlords in the form of public housing aid. Recently, a local government official in charge of public assistance benefits in the Kanto region received a phone call from the landlord of an apartment where one tenant was a benefit recipient. The owner told the official that the recipient had not paid rent for three months. The local government had provided the recipient with cash to pay the rent. Although the recipient told the official that he had "lost" the money, neighbors said he had often gone to a keirin cycling racetrack.

Image Sources: 1) 2) Doug Mann Photomann 3) 4) Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013