CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC

19th century koto player Japanese music derives from an ancient tradition whose folk origins and early influence from the Asian continent are wrapped in the midst of history. It also comprises the associated musical tradition of Okinawa and the autonomous tradition of the Ainu people of Hokkaido. “Gagaku “is a type of music, strongly influenced by continental Asian antecedents, which has been performed at the Japanese imperial court for more than a millennium. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

In Western music an octave consists of 12 pitches. Played in succession they are called the chromatic scale and seven of these notes are chosen to form a normal scale. The 12 pitches of an octave are also found in Japanese and Chinese music theory. There are also seven notes in a scale but only five are considered important. In Western music a scale structure can begin at any one of the 12 notes, but one axiom of Japanese music theory is that scales begin on only five of the 12 pitches.

There is no standardized musical notation for Japanese music. The notation often varies from instrument to instrument and school to school, and is usually kept secret. The notation for the shakuhachi flute is read top to bottom, right to left. Strings of notes are written in the equivalent of Do, Re. Mi.

“Dengaku”, or “kokori”, is a style of ritual music performed with sasara odori dance and thought to be 1,400 years old. Still performed in the Gokayama area of Toyama Prefecture, it is played with an instrument called an “itasasara”, which looks like a giant centipede and is comprised of 108 small wooden boards and a pair of handles placed together. The number 108 is sacred in Buddhism. Playing the instrument is said to cast away mankind’s 108 earthly desires.

Some forms of traditional Japanese music developed in close association with Kabuki drama, Noh theater, odiri dance and other arts. Music from Kabuki drama and Noh theater consists of a solo male singing accompanied by flute, drums, and samisen, and is characterized by the predominance of vocal over instrumental music.

Gagaku, Hayachine Kagura, a performance of sacred Shinto music and dance of Iwate Prefecture, and Dainchido-bugaku court music and dance of Akita Prefecture were added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2009.

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Traditional Music. Columbia records site jtrad.columbia.jp ; Good Photos of Traditional Instruments at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Pro Musica Nipponia promusica.or.jp ; Gagaku gagaku.net ; Good Photos of Gagaku at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Heian Kyou heiankyou.com ; Japan Gagaku Society nihongagakukai.gr.jp ; Koto no Koto kotonokoto.org ; Koto Music Home Page asahi-net.or.jp ; International Shakuhachi Society komuso.com ; Kids Web Japan web-japan.org/kidsweb

Links in this Website: CLASSICAL JAPANESE MUSIC Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; WESTERN CLASSICAL MUSIC IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE FOLK MUSIC AND ENKA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; J-POP AND POP MUSIC IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; J-POP AND POP ARTISTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ROCK IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PUNK, FOREIGN MUSIC, HIP-HOP IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; YOKO ONO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; KARAOKE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; DANCE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Music: “The Rough Guide to the Music of Japan” is a CD assembled by Paul Fisher, Short Introduction to Japanese Music asnic.utexas.edu ; Bibliography on Music in Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ;Traditional Japanese Music and Dance sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww ; Wikipedia article on Music of Japan Wikipedia ; Performing Arts Network of Japan performingarts.jp ; Traditional Performing Arts in Japan kanzaki.com ; Hear Music, a World Music Store with a hearjapan.com ; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com ; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

Learning Classical Japanese Music

19th century geisha

playing a flute Classical Japanese music has a different philosophy than Western music. Form is often emphasized over content. In accordance with the concept of “hogaku”, stress is placed on the position of the instruments, posture and handling the instrument with the understanding that if a musician can get these things right then good things will follow. Also part of this idea is that if you get the form right a spirit will enter you and give you the skill to play well.

The process of learning hogaku is called “keiko”, which essentially means exercise. Teachers spend a lot of time teaching form, sometimes with things like social etiquette, proper dressing and grooming and carrying oneself in a dignified manner included. Unlike Western musical students who are taught to practice and drill, Japanese musical students are taught to mimic their teachers and immerse themselves in the music.

There is relatively little interest in Japanese classical music among the younger generation today. When there are classes they are comprised mostly of girls. Girls also make the majority of school brass bands and Western music orchestras. Boys are more interested electric guitars and hip hop dancing.

Book: “Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instrument” by William Malm (Kodansha International, 2001)

Gagaku Music

“Gagaku” is a form of 1,200-year-old Japanese court music that is still played today by a government-subsidized family ensemble with 20 or so wind, string and percussion instruments. Gagaku means "elegant music." Most of the music is monophonic and Westerners generally find it unappealing, stiff and too formal.

Gagaku has it origins in 2000-year-old music from China and Korea. It flourished between the 8th and 12th centuries and then declined until the Meiji period when it was revived as music for the Imperial Court. In ancient times, nobles were expected to be accomplished gagaku performers and studied singing, dancing and instrument playing.

Gagaku is divided into “kangen” (instrumental), “bugaku” (music and dance), “kayo” (songs and chanted poetry) and into festival and recital music. Though it resembles a Western-style orchestra, in that it has string, wind and rhythm sections, gagaku music emphasizes the wind section. Every note in gagaku is significant. A single tone can present a color, season or even something like an internal organ. Spring notes are more cheerful and warm while autumn notes are more sorrowful.

In the old days n orchestra was divided into two sections. The section on the "right" dressed in green, blue and yellow and played Korean music. The section of the "left" dressed n red and played Chinese, Indian and Japanese music. Modern orchestras usually have 16 players.

History of Gagaku Music

“ Gagaku “is made up of three bodies of musical pieces: “ togaku”, said to be in the style of the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907); “ komagaku”, said to have been transmitted from the Korean peninsula; and music of native composition associated with rituals of the Shinto religion. Also included in “ gagaku “are a small number of regional Japanese folk songs, called “ saibara”, which have been set in an elegant court style. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“An extensive collection of musical styles was transmitted to Japan from the Asian continent during the Nara period (710-794). In the Heian period (794-1185), these were ordered into two divisions, “ togaku “and “ komagaku”, and performed at court by nobles and by professional musicians belonging to hereditary guilds. With the rise of military rulers in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), “ gagaku “performances at court languished but the tradition was preserved in the mansions of the aristocracy and by three guilds of musicians situated in Kyoto, Nara, and Osaka.

“Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the guild musicians were assembled in the new capital of Tokyo. The musicians who serve today in the Imperial Palace Music Department are, for the most part, direct descendants of members of the guilds formed in the 8th century.

Japanese Religious Music

The most prominent type of Japanese religious music is that of Shinto ritual. The earliest extant description of Shinto music, or “ kagura “(music of the gods), is preserved in the myth of the sun goddess Amaterasu, who, having been offended by her brother, has hidden her light in the Rock-Cave of Heaven. She is lured out by a dance set to music, performed by the goddess Ama no Uzume no Mikoto. The myth echoes the convention that the gods are invoked to witness a performance and, by so doing, revitalize the community. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“ Mikagura”, or court “ kagura”, is distinguished from “ sato kagura”, or village “ kagura”, which comprises a range of local music associated with particular regions or shrines. Village “ kagura “may be heard on the occasion of festivals, when musicians accompany their songs on transverse flutes and a variety of drums.

Japanese Court Musicians

8th century court instruments The Japanese Imperial Family and the Imperial Palace have their own gagaku orchestra. Court musicians are officially known as "maintainers of a significant intangible cultural asset." They play gagaku music at official lunches, diners and public events. Robert Poole wrote in National Geographic the "shrill pipes and silk strings sounded like something made more for gods than mortals.”

When performing gagaku musicians sit cross-legged on a raised dais, all wearing identical costumes and play highly formalized music, which "blends together with stunning timbres and harmonies." The chief court musician said, "It takes about seven years of apprenticeship" to learn the whole repertoire by heart. "That is so we can play it in the dark" when some court ceremonies take place.” Hideki Togi, a handsome gagaku musician who left his place as a court musician at the Imperial Place to put out New Age records, said, "As a member of the Imperial Ensemble he was a civil servant, and my hours were set from 9 to 5 and there were a lot of ceremonial occasions."

Gagaku musicians begin studying after graduating from high school. During their rigorous seven year apprenticeship they learn to play several ancient instruments, and to sing and dance traditional music. They also learn to play Western instruments because foreign dignitaries at the Imperial Palace are often entertained with Western classical music

Some gagaku musicians come from families of musicians that trace their ancestry back to the Nara period (710-794). Only men are allowed to play in the ensemble. The chief court musician said, "I'm afraid that the family tree is dying...My family has been doing this for 500 years, since they came from China." He said the tradition couldn't continue because he three daughters and only males can carry on the tradition.

Classical Japanese Instruments

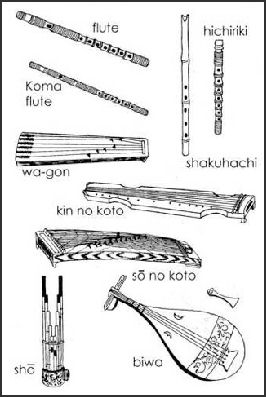

The short-necked lute (“ biwa”), the zither (“ koto”), and the end-blown flute (“ shakuhachi”) were all introduced from China as early as the 7th century, and were among the instruments used to play “ gagaku”. The “ shamisen “is a three-stringed plucked lute that is a modification of a similar instrument introduced from Okinawa in the mid-16th century. Combinations of these four instruments, along with the transverse flute (“ shinobue”) and small and large drums, comprise the ensembles of traditional Japanese music. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

During the 17th century, music developed for common people that utilized the “shakuhachi” (a vertical bamboo flute with lovely, ethereal quality), “samisen” (a banjo-like, three-stringed plucked instrument) and “koto” (a zither-like instrument). The music created by these instruments is quite different than that of Western music. Gagaku instruments include the “yokobue” (a kind of flute), the so (a 13-stringed plucked lute that is the predecessor of the koto), the “biwa” (a pear-shaped, lute-like instrument with four strings), and a variety of gongs, chimes, and “taiko” (drums). The biwa and other stringed instruments were usually played by the highest-ranking nobles.

Three wind instruments in Gagaku play the main melody and symbolize the heaven, sky and earth. They are the “hichiriki” (an oboe-like double reed pipe with nine holes), the “sho” (a cylindrical, standing reed-pipe mouth organ with 17 bamboo tubes, each having a single reed), and the “ryuteki” (a bamboo flute with seven finger holes).

A sho-type musical instrument from the 8th century was found in Nara. It is made of 17 small bamboo pipes set on a wooden receptacle with a pipe-like lacquered mouth piece with images of celestial children, birds in heaven and butterflies.

Koto

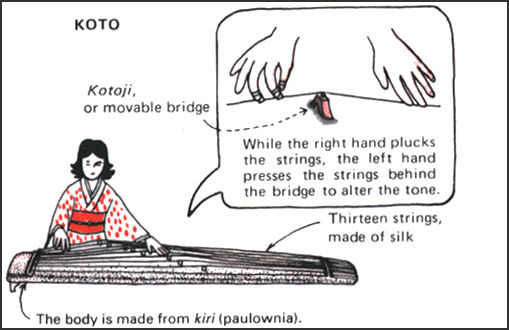

The koto was imported from China about 1300 years ago and was mentioned in the “The Tale of Genji”, written in the 11th century. Looking like a cross between a harp and an autoharp and related to the Chinese “zheng” and Korean “kayagum”, it has 13 strings and is played flat on the floor. A bass koto with 17 strings was developed in the 20th century.

“The earliest “ koto “had only five strings (later six) and was about a meter long. In the Nara period (710-794), the thirteen-stringed “ koto”, measuring about two meters in length, was introduced from China and used in the court music ensemble. The “ koto “is made of paulownia wood, has a movable bridge for each string, and is plucked with picks attached to rings worn on the thumb and first two fingers of the right hand. The left hand is used to raise the pitch of strings or modify tone.

The koto musical scale is pentatonic but does not include the sounds “re” and “so” in the Western seven-note scale. The instrument is tuned by moving the frets under the strings. Early versions of the koto were simply a piece fo wood with strings pulled across it. Modern versions have a hollow body and are made mostly by hand in Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture.

The best kotos are made of high-quality paulownia wood that has been exposed to the elements for about a year. The wood is scorched to reveal the wood grains and treated against insect damage. To produce a rich sound groves are carved into the piece of wood used on the interior.

Curtis Patterson, a koto teacher, said he was attracted to the instrument because of its human quality. “When playing,” he told the Daily Yomiuri, “you are constantly in direct contact with the instrument, using your hands not to pluck the stings, but also to delicately modify the tone and pitch in so many ways. Because of this the instrument becomes almost an extension of the performer, conveying subtle moods and deep emotions in a very organic way.”

The “ yagumogoto” is a two-string koto with a distinctive plaintive sound, The instrument was used in the Asuka period in the 6th century to provide music for shinto rituals and waka poem readings. The instrument is still played by a woman’s group n the Asuka area.

Biwa

The biwa was derived from a similar lute-like instrument introduced from China in the 8th century. It was a favorite instrument of traveling minstrel-like, often blind, musicians who went from town to town chanting sutras to the accompaniment if the biwa. In the Heian period the biwas was incorporated into Imperial orchestras and later became a favored instrument of storytellers and balladeers.

In court music, the “ biwa “plays simple figures to accompany the melodic instruments of the “ gagaku “ensemble. Although the “ biwa “never came to be used in solo instrumental performances, there is a record of its use by itinerant lay-priest entertainers (“ biwa hoshi”) to accompany their recitations of stories. From the 13th century on, the most important work in this repertoire was the “ Heike monogatari “(“ The Tale of the Heike”), a lengthy history of the downfall of the Taira military clan at the hands of the Minamoto clan. The “ biwa “is a four-stringed lute that is plucked with a large plectrum.

A beautifully-decorated, five-string biwa, dated to the 8th century is part of the Shosoin collection in Nara. The instrument is 108 centimeters long and 31 centimeters wide. It is decorated with flowers and pieces of seashell that were glued on to the rosewood body of the lute using a technique called raden. Wear on the neck indicates the instrument was probably played.

Raden Shitan no Gogen Biwa Lute

The “Raden Shitan no Gogen Biwa “ — five-string lute, red sandalwood lute — is one the best-loved of the Shoso-in treasures. The techniques used to produce the treasures include raden, in which beautiful shells are broken and the pieces are arranged into patterns, and mokuga, in which music instruments and boxes are decorated with flowers and birds fashioned from gold, silver and various types of wood.

The “ Raden Shitan no Gogen Biwa “ believed to be the only five-stringed, lute-style wooden biwa in existence (most biwas have four strings). The lute bears an image of a Persian playing a biwa lute while riding a camel, as well as birds and a tropical tree in mother-of-pearl inlay on the pickguard. The back of the instrument is decorated with a gorgeous Chinese-style flower pattern, elaborately depicted also in mother-of-pearl inlay.

Stringed instruments from the period were usually strung with wound silk which is said to have a very warm sound. Scratches have been found on the tortoiseshell pickguard, which appears to indicate the instrument was actually played with a plectrum.

On the Shoso-in five-string sandalwood biwa violinist Iluku Kawai told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “This is a breathtakingly beautiful, graceful lute...The elaborate, elegant design featuring a camel and tropical plants in the lute's mother-of-pearl inlays portrays culture from the continent. The lute conveys to me the dedication of the craftsmen who painstakingly created a lute that also is a piece of artwork.” [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 27, 2010]

“I get excited just imagining how performers from the Tenpyo times (from the end of the seventh century to the mid-eighth century) would have played this instrument. Compared with a four-string lute, a five-string one has a wider range — from masculine bass to delicate soprano. I believe this lute would produce a deep, heavy, melancholic sound. I love the tone and rhythm of music from the Silk Road. Just listening to it stirs up eerie feelings inside me.”

Hideki Togi

Hideki Togi is a handsome gagaku musician who left his place as a court musician at the Imperial Place to put out New Age record and perform in front of adoring female fans. Togi has released a half dozen or so recordings and sold hundred of thousands of CDs.

Togi plays the hichiriki, sho and ryuteki, sometimes backed by synthesizers, cellos, electric guitars and bass. He comes a long line of court musicians and quite because he was tired of the rigid court life and wanted to explore his own music.

Togi's music has been played at planetariums and Christmas displays. departure from the Imperial Ensemble was not well received. Only about one musicians every hundred years does this in part because it takes so much training to become an Imperial musician. When he plays classical music he said he tries to recreate the atmosphere of the Heian period (794-1192) by wearing clothing like that worn by nobles at that time — a kariginu robe made of silk and eboshi brimless headgear, burning incense and using stage sets that conjure up the period.

Shakuhachi

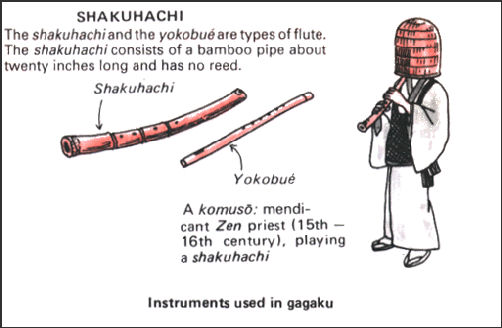

The “ shakuhachi “is an end-blown bamboo flute with a notched mouthpiece. In the 7th century it had, like the Chinese model, six finger holes, but today has only five, four being placed equidistant on the front face with a thumb hole set into the rear face. In the late 17th century, the “ shakuhachi “was taken up by the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhist priests, who established its playing as a spiritual discipline.

“ The shakuhachi is believed to have evolved from flutes that first appeared in ancient Egypt and arrived in Japan via China about 1,400 years ago. It has a long association Zen and is said to have a meditative quality because its sound is so closely linked with human breath. With no valves or reed it is deceptively simple instrument made of a piece of bamboo with holes. It produces a rich, mellow sound that it intimately related to the bamboo from which it is made. Its name come from its length in Japanese measurements (equaling 58 centimeters). One “shaku” is equal to 7.25 centimeters. “Hachi” is “eight.”

Patterson Clark, an American who studied the shakuchi in Japan, told the Washington Post, the shakuhachi is “notoriously difficult to play...It forces a face-to-face confrontation with expectation, self-criticism, disappointment, frustration, and impatience — all in a single breath. Exhaling through all these impediments and releasing one’s attachments to them can dissolve the ego so that one experiences only the sound — and become the sound.”

The shakuhachi is played very softly. Master musician Yoshio Kurabashi told the Washington Post, “The loudest tone is at the start of the first note of the phrase. As the breath continues, the sound grows softer until it fades into silence.” Notes can be flattened, bent, overblown and played with different fingering. By one count 64 sound can be made in each octave.

A bamboo shakuhachi flute from the 8th century found in Nara is 43.7 centimeters long and 2.3 centimeters in diameter and engraved with images of four women picking flowers and playing the biwa lute along with images of flowers, butterflies and birds.

Shakuhachi Music

Shakuhachi music is popular among those who like their music soothing and meditative. It has a long association with Buddhism and has traditionally been played by some Zen monks.

Many shakuhachi songs played today are more than 500 year old. In the 16th and 17th centuries shakuhachi it were played by wandering Komosu monks who played the flutes as the walked through the woods in their quest for enlightenment.

Highly-regarded shakuhachi musicians include Hozan Yamamoto, an innovator and composer who has worked wit people like flutist Jean Pierre Rampal, sitar-player Ravi Shankar and jazz clarinetist Tony Scott; and Akikazu Nakamura, a renowned composer who tried to incorporates his love for Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa into some of his pieces. Nakamura plays the Tohoku style shakuhachi and studied at Berklee and the New England Conservatory in the United States.

Komuso

Komuso a group of people who play shakuhachi flutes with strange-looking wicker basket covering their heads. In the old days komuso were priests of the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism. Many were ronin (masterless samurai) who adopted the ascetic komuso lifestyle and played on the streets for alms. Today many komuso are middle aged men.

Komuso means “straw hat monk.” Their original aim was to withdraw from the world and become “komuso” (“monks of nothingness”). The baskets are worn over the head for anonymity. In the old days some carried knives but were only allowed to fight on temple grounds. During the Edo period komuso were sometimes employed by the shogun as spies. At the end of the shogun era, the group had discipline problems and was banned in 1871. Most of the sect’s temples were destroyed or dismantled but the sect continued to live on in a small enclave in Kyoto and now is sort of like of club. .

The shakuhachi was used as a meditation tool and, some say, a club. One komuso member told the Daily Yomiuri, "Once I begin playing the shakuhachi, I feel as if I am attaining a state of selflessness. It is also good for your health, because playing shakuhachi requires you to adopt the art of abdominal breathing, just like zazen practice of Buddhist meditation."

Decline of Japanese Traditional Music

Since the Meiji Period emphasis has been steadily shifting away from traditional Japanese music to Western music. The shift has been so dramatic that school children hardly learn anything about traditional Japanese music anymore but are proficient at playing Western-style recorders and keyboard harmonica (a keyboard with a long plastic tube that the player blows into).

To rectify this situation, the Education Ministry made new rules that went into effect in April 2002 that requires elementary schools students to be exposed to Japanese traditional music and learn the concept of “hogaku” and requires that middle school students should learn how to play traditional instruments.

Some school have trouble complying with the new rules because they can't afford the instruments. To address this problem companies have experimented with making shakuhachi flutes from poly vinyl chloride water pipers rather than bamboo. Nobody has figured about how to make a cheap samisen or koto. Image Sources: 1) 2) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 3) Liza Dalby Genji site (Heian instruments 4) and 5 ilustrations and diagrams of koto and shakuhatchi JNTO 6) Japan Zone (biwa)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012