SHINTO ARCHITECTURE

small Shinto shrines Followers of Shinto believe that a “ kami “(deity) exists in virtually every natural object or phenomenon, from active volcanoes and beautiful mountains to trees, rocks, and waterfalls. Shinto shrines are places where “ kami “are enshrined, and also where people can worship. Rather than follow a set arrangement, shrine buildings are situated according to the environment. From a precinct’s distinctive “ torii “gate, a path or roadway leads to the main shrine building, with the route marked by stone lanterns. To preserve the purity of the shrine precinct, water basins are provided so that worshippers can wash their hands and mouths. “ Komainu”, pairs of lionlike figures placed in front of the gates or main halls of many shrines, serve as shrine guardians. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The Temporary main halls were constructed to house the “ kami “on special occasions. This style of building is said to date from about 300 B.C. The main shrine building of the Sumiyoshi Shrine in Osaka is similar to this temporary building type and is thought to preserve the appearance of ancient religious buildings. The other major style for the main hall draws its simple shape from the granaries and treasure storehouses of prehistoric Japan. The best example of this style is the Ise Shrine, in Mie Prefecture. Its inner shrine is consecrated to Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess. The outer shrine is dedicated to the grain goddess, Toyouke no Omikami. Elements of residential architecture can be seen in the main building of the Izumo Shrine in Shimane Prefecture, as evidenced by columns set directly into the ground and elevated floors.

“The nature of Shinto worship changed, following the introduction of Buddhism, and shrine buildings borrowed certain elements from Buddhist architecture. For example, many shrines were painted in the Chinese style: red columns and white walls. It was a tradition to reconstruct shrine buildings regularly to purify the site and renew the materials (a practice still followed at the Ise Shrine every 20 years). For this reason, and also as a result of fire and other natural disasters, the oldest extant main shrine buildings date back only to the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS) Terminology Search http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus ; Herbert Offen Collection Peabody Essex Museum ; Japanese Architecture in Kansai kippo.or.jp/culture ; Wikipedia article on Japanese Architecture wikipedia.org ; Japanese Architecture in Kyoto kyoto-inet.or.jp ; About Japan: Architecture csuohio.edu ; Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com ;

Houses in Japan: Japanese Houses on KidsWeb web-japan.org/kidsweb ; About Homes csuohio.edu/class ;Traditional Japanese Design eastwindinc.com ; Businessweek Piece on Micro Homes images.businessweek.com ; Japanese Design japanesehomeandbath.com ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Housing Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; Traditional Japan, Key Aspects of Japan japanlink.co ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles with a section on traditional houses (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese) shirofan.com ;

Thatch Roof Houses of the Shokawa Valley: Shirakawa Grasso Houses shirakawa-go.org/english ; Japan Guide japan-guide JNTO article JNTO Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO Utsukushi-ga-Hara Open Air Museum Website: JNTO article JNTO

Castles : Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Edo Castle us-japan.org/edomatsu Matsumoto Castle on Matsumoto City tourism welcome.city.matsumoto.nagano.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia Nagoya Castle Official site nagoyajo.city.nagoya ; Himeji Castle Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Himeji castle virtual tour himeji-castle.gr.jp ; Himeji Tourist Information himeji-kanko.jp Himeji Tourist Information Map himeji-kanko.jp UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website ; Osaka Castle Osaka Castle Site osakacastle.net ; Japanese Castle Explorer .japanese-castle-explorer.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia Osaka Castle Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO

Shinto Shrines

Sanctuaries for kami, or shrines, are called “jinja”. These usually consist of a building surrounded by trees. Most Shinto buildings are shrines (a sacred place for praying) not temples (places of worship). Temples in Japan are usually associated with Buddhism. Classical Shinto shrines were not built to dominate nature and leave the observer awestruck, as many Western cathedrals were intended to do, rather they were built to harmonize and fit in with their natural surroundings. Shinto shrines are usually small in size and sometimes are so ensconced in trees they are difficult to see.

There are around 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan. Almost every neighborhood has one. Most shrines have associations with specific gods and kami. But these are not fixed. It is not unusual for shrines to add new gods to address the needs of followers.

In the early days of Shintoism there were no Shinto shrines. Worshipers gathered and performed simple rites near sacred objects such as “sakaki” trees (now present at every shrine). The earliest Shinto shrines were sacred places marked off with special ropes (“shimenawa”) and strips of white paper (“gohei”). Fences and torii gates were introduced later. Ropes, white paper and torii gates are now common features of all shrines.

Shinto shrines come in various shapes and sizes. The architecture of most of them is believed to be based on wooden storehouses and dwellings from prehistoric times. Shrines that adhere strictly to architecture of these old buildings are known as "pure" style. The best examples of the "pure" style can be found at Ise shrine.

Main Shinto Buildings

Within the shrine grounds is 1) the main shrine (“haiden”), a place of worship where people pray, usually located at the rear of the ground; 2) a main sanctuary (“honden”), a sacred place namely off limits to lay people, where the kami of the shrine is believed to dwell; and 3) a hut-like pavilion for purification, where people rinse their hands and mouth with water taken from a basin (“chozuya”).

Shinto shrines has virtually no images or idols but they do have symbols. The inner sanctuary of these shrines, most of which haven't been opened in decades, contain a bronze mirror, (representing the sun and the sun god), and the sword and the jewel (symbolizing those given to Jimmu, the first emperor) and little else. Only Shinto priest are supposed to enter this sanctuary.

The main sanctuary is generally composed of front porch, where people pray, with a rope, a bell and a collection box. Beyond the porch is a small hall, where Shinto priests perform rituals and blessings, particularly on New years Day

Features of Shinto Shrines

Features of "pure" style shrines include natural wood columns and walls (as opposed to painted red and white ones), thatched roofs, horns (“chigi”) that stick out from the top of the roof, gabled ends, short logs (“katsuogi”) that lay horizontally across the ridge of the roof and free-standing columns that support the ride of roof at the ends.

Most shrines have elements of Chinese temple architecture that were incorporated into the shrines after Buddhism was introduced in the 6th century Features of "Chinese" style shrines include painted red and white columns and walls, tile roofs, Chinese-style upturned eaves, and detailed carvings and ornamentation below the eaves.

Special ropes and hanging tassles (“shimenawa”) and strips of white paper (“gohei”) date back to ancient times when they were used to mark off sacred places. Below some shrines is the vestige of a sacred sakaki tree called the heart post. Many temples and shrines are filled with small shops selling religious items.

Shimenawa have traditionally been placed above the entrance of the main temples to mark it as a holy sight. They can be huge, The ropes can weigh 200 kilograms and the tassels, which resemble bundles of drying rice, can measure 1.5 meters in height. They are put in place with a crane.

The world's thickest ropes are at Izumo shrine, one of Japan's oldest shrines. Weighing six metric tons, the ropes are made twisted rice-straw strands as thick as a human being. Smaller versions of these ropes are kept at almost all Shinto shrines to ward of evil spirits. The world's largest rope is 564.3 inches long, 5 feet in diameter, and weighs 58,929 pounds. It was made of rice straw for the annual festival in Naha in Okinawa in October 1995.

The entrance of shrines are often guarded by stone statues of Chinese lions or Korean dogs. These menacing-looking statues usually appear in pairs. On one side of the gate one has an open mouth, spitting out good luck. One other side is one with a closed mouth, catching evil. Rice temples are guarded by foxes, clever animala regarded as a kami messengers and symbols of fertility.

Torii Gates and Stone Lanterns

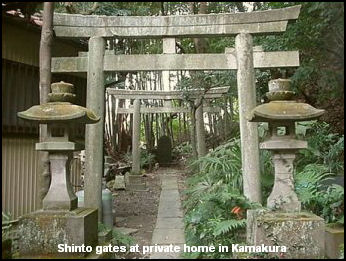

A red-orange “Torii” gate signal that you are about to entered a sacred place and should act accordingly. It consists of two upright pillars with two crossbeams at the top. Large shrines often have large torii gates, Large shrine grounds sometimes have many tori gates.

Ancient gateways were always made of naturally colored cypresses but entrances today may be composed of wood, stone, bronze or even concrete. A gateway painted red shows Chinese-Buddhist influence.

The pathway to a shrine is often lined with stone lanterns donated by worshipers. Stone lanterns are a fixture or many temples, pilgrimage routes and gardens and well as shrines. The design used in most lanterns originates from Korea. Some stone carvers regularly visit South Korea to get inspiration and gain insight into how the originals were created.

Most stone lanterns today are made by machines but some are still made by craftsmen using traditional manual techniques following images in their mind. . Quality ones are made with capstones with cylindrical cores that hold the parts of the lantern together lightly even during an earthquake.

Craftsmen use a wide range to tools to shape the stone, including simple hammers and chisels. Lines are drawn with ink in the parts of the stone to be carved. After they are carved lanterns are exposed to rain and wind for at least three years so the gain the characteristics of wabi, or profoundness.

Ise Shrine

The Shrine of the Shinto Goddess in Ise near Nagoya is the most sacred place in the Shinto religion and one of the best examples of traditional Japanese architecture. Founded in A.D. 690, it has been rebuilt every 20 years (with a few exceptions) since A.D. 690 from scratch in a process that half construction and half ceremony.

The main sanctuaries of Shrine of the Shinto Goddess Ise are beautiful austere structures made of new hinoke (Japanese cyprus) beams in what is said to be the purest and simplest style of Shinto architecture. "Here, better than anywhere else," writes historian Daniel Boorstin, "we witness the distinctive Japanese conquest of time by the arts of renewal. Here, too, we can see how Japanese architecture has been shaped by the special qualities of wood, and how wood has carried the creations of Japanese architects on their own kind of voyage through time."

The architecture is in the form of traditional Japanese rice storehouse. The supporting columns pass through a raised floor and inserted directly into the ground. Responding more to natural principals than architectural ones, these columns are much thicker than is necessary to hold up the structure. They are the shape and thickness of a live tree and are placed in the ground and suck up moisture like a live tree.

No nails are used, only dowels and interlocking joints. The roof is thatched with miscanthus grass. The wood is unvarnished and unpainted, displaying the wild beauty of the cypress's natural texture. There are crossbeams at either end of the roof. and large rounded logs on the ridge of the roof. Protruding from the upper part of the gable at either end of the building are metal-tipped poles that add structural symmetry.

Ise Renewal Ceremony

Every sanctuary consists of two identifiable adjoining sites. Since the 7th century A.D., with only a few exceptions, the main sanctuaries are rebuilt every 20 years and the symbols of their kami are taken from the old sanctuary to the newly constructed sanctuary. By performing this ritual the Japanese people receive renewed blessing from their kami and play for world peace.

The shrines were rebuilt for the 61st time in 1993 at cost of $60 million. The next time they will be rebuilt is in 2013. The reason for the periodic rebuilding is not clear. Some have suggested it is away of keeping traditional carpentry techniques alive. Other believe it might have to do with ancient tradition of rebuilding and relocated the places of a new emperor after the old emperor died.

Every effort is made to make sure the new structure is as elegant as the one it will replace. Selection of the hinoki from a special forest begins ten years in advance. After the new site and the wood is purified by Shinto priests, local residents in ceremonial white robes haul 16,000 cypress timbers using wagons to the site and white pebbles are tossed on the inner precincts of the two main shrines to indicate they are off-limits.

The sacred treasures and apparel which are offered to the kami are also remade. There are 125 kind of sacred apparel, 1085 objects, 491 treasures and 1,600 accessories. They are all remade by skilled craftsmen in accordance with exact traditional specifications.

After the new sanctuary is completed an elaborate nighttime ceremony, called the Offering of the First Fruit takes place in which the symbols of the kami are placed in a series of special containers and carried with in a long silk shroud, along with sacred treasures, apparel and accessories, from the old sanctuary to the newly constructed sanctuary. The wood from the old shrine is sued to construct the torii gate at the entrance of the shrine or given to shrines elsewhere in Japan.

Buddhist Architecture in Japan

When Buddhism came to Japan in the sixth century, places dedicated to the worship of Buddha were constructed, their architectural forms originating in China and Korea. In each temple compound, a number of buildings were erected to serve the needs of the monks or nuns who lived there and, as importantly, to provide facilities where worshippers could gather. In the eighth century, a group of buildings comprised seven basic structures: the pagoda, main hall, lecture hall, bell tower, repository for sutras, dormitory, and dining hall. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Enclosing the entire temple compound was an earthen wall with gates on each side. It was common for a gate to have two stories. The main hall contained the most prominent object of worship. The lecture hall, which in early temples was most often the largest structure, was used by monks as a place for study, instruction, and performing rituals.

“Two types of towers predominated: one with bells that announced the times of religious observance each day and another in which canonical texts were stored (the sutra repository). Behind or to the side of the inner precinct stood refectories and dormitories. The buildings of the temple complex were generally arranged in a geometric pattern, with variations between sects. The main buildings at Zen temples were frequently placed in a line and connected by roofed corridors, and the temple complexes of Pure Land Buddhism often included gardens and ponds.

Japanese Buddhist Temples

There are 70,000 Buddhist temples in Japan. They are places of worship not shrines (sacred places for praying). Shrines are usually associated with Shintoism. A temple generally contains an image of Buddha and has a place where Buddhists practice devotional activities. Temples attract large crowds during festivals or if they are famous but otherwise a fairly quiet. They are often sought as places for quiet meditation, with most acts of worship and devotion being done in front of an altar at home.

Buddhist temples are generally clusters of buildings, whose number and size depends on the size of the temple. Large temples have several halls, where people can pray, and living quarters for monks. Smaller ones have a single hall, a house for a resident monk and a bell. Some have cemeteries.

The architecture of Buddhist temples is influenced by the architecture of Korea and China, the two countries that introduced Buddhism to Japan.

Early Japanese Buddhist temples consisted of pagodas, which were modeled after Chinese-style pagodas, which in turn were modeled after Indian stupas. Over time these pagodas became one building in a large temple complex with many buildings.

Buddhist temples built in the 7th century featured vermillion-painted columns and eaves supported and decorated with mythical beasts sculpted in "dry-lacquer" (layers of hemp cloth glued together and covered with lacquer) or guilt bronze. Unfortunately no original examples of this style of architecture remains. The earliest Buddhist paintings had a strong Indian influence.

Types of Buddhist Temples and Buildings in Japan

There are three main types of Buddhist Temples: 1) Japanese style (“wayo”), 2) Great Buddha style (“daibutsuyo”), and 3) Chinese style (“karayo”). These in turn vary according to the Buddhist school and the historical period in which they built.

The main hall (“kondo” or “hondo”) is usually found at the center of the temple grounds. Inside are images of the Buddha, other Buddhist images, an altar or altars with various objects and space for monks and worshipers. The main hall is sometimes connected to a lecture hall.

A monk at Mtizuzoin Temple in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri,”When people think of temple, they tend to think of it as a shadowy, scary kind of place. This is because temples have long been regarded as being associated with death. This stems from the fact that many people only visit the temple for Buddhist rites for the dead.

Other buildings include a lecture hall (“kodo”), where monks gather to study and chant sutras; the sutra depository (“kyozo”), a place where Buddhist scripture are kept, and often shaped like a log cabin on stilts; living, sleeping, and eating areas for monks; and offices. Large temples often have special halls, where treasures are kept and displayed. Some have a pagoda. Many temples have small shops that sell religious items.

Features of Buddhist Temples in Japan

Japanese style pagodas have multiple stories, each with a graceful, tiled Chinese-style roof, and a top roof capped by a spire.

The central images in the main hall is often surrounded by burning incense sticks and offerings of fruit and flowers. Inside the temple there is one set of wooden plaques with the names of large contributors and another set the afterlife names of deceased people. In the old days the afterlife names were only given to Buddhist priests but over time they were given to lay people who paid enough money and now are almost used as ranking system in the after life.

Many Buddhist temples contain large bells, which are rung during the New Year and to mark other occasions, and cemeteries.

Many temples use concrete that has been expertly camouflaged to look like wood. Near many Buddhist temples are stone Jizo figures with red bibs and a staff in one hand and a jewel in the other. They honor the souls of children who have died or been aborted. See Above.

Castles and Donjons in Japan

Japanese style castles (“donjons”) are beautiful structures that are unlike castles found in other countries. Usually built on a hill overlooking a town or city, they are comprised of large multi-storied, pagoda-like keeps that look like a large houses at the center and stone walls made of large stones and sometimes surrounded by wide moats.

There are three kids of fortifications in Japan: mountain castles; hill castles and castle built on plains. Every daimyo used have a castle and the castles themselves varied a great deal in size.

The main tower or keep is known as the tensu. Some castle had a single tensu. Large ones had several tensu arranged around a larger one. Smaller building built on the ramparts were made of wood but covered with plaster that protected them it from fires and firearms.

Many castles were built with elaborate mazes of halls, corridors and tunnels that allowed members of the court to go about their lives discreetly and made escapes possible if the castle walls were breached by enemies.

The entire structure is surrounded by an imposing defensive walls and moats. The walls have triangular and circular holes used for firing guns and arrows. Openings in the main keep were used for pouring boiling oil and dropping rocks on attackers.

A great deal of labor was required to build the massive stone walls and moats. The stones used in the walls weighed as much as 130 tons and required a great effort to move uphill. Digging out moats also required a lot of work.

History of Japanese Castles

The first Japanese castles were simple mountain forts which relied as much on location as structures for defense. The problem with these structures was they were often built in places that were inconvenient or far from the best places to live and raise crops. Sometimes made or upright logs they were used during times of hostility.

The "plain castles" found in Japan today developed from residences of daimyos usually built on flat land in the middle of the town that protected it. Later, donjons were built on top of raised stone platforms and the towns were built around them.

After the Ronin Rebellion of 1467, Japan entered the Period of Civil Wars and castles became increasingly important for defense and survival. Many great Japanese castles — Osaka-jo, Himeji-jo and Fushimi-jo — were build during this period.

In 1615, the Tokugawa shogunate proclaimed that each domain could maintain only one castle to reduce the threats on its power. This resulted in the destruction of many small castle. Remaining castles were not used much during the long period of Edo peace. In 1873, the Meiji government ordered the destruction of 144 castles, leaving only 39 left. Of these all but 12 were destroyed in World War II.

Of the 12 remaining castles four-Hijemi, Hikone, Matsumoto and Inuyama — have been designated national treasures. The 1960s was a period of frantic castle reconstruction. Most of these were built from concrete and were restored or rebuilt for he benefit of tourists.

Himeji Castle

Himeji Castle in Himeji south of Kobe is regarded as the best of Japan's castles and one of the few with some its original interior and exterior intact. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, it was built between 1601 and 1609 by Ikeda Terumasa, the son-in-law of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Unlike other castles in Japan, it has managed to avoid being destroyed by a fire or natural disaster and was never attacked. It has undergone some major restorations but always in accordance with designs and construction methods used to make the original.

Standing 46 meters high, Himeji is known as the White Egret Castle because all the structures are white and from a distance the castle looks like a white bird in the middle of some rice fields. Constructed of wood, plaster and stone, its features a seven-story-high, five-tiered donjon with platforms of white stone and a white plaster exterior, three smaller donjons, a three-story watchtower, and covered passages connecting the donjon with the towers.

Himeji Castle sits on a site were a fort was built in 1333 and an earlier castle was built in the middle of the 16th century. The entire structure is surrounded by imposing defensive walls and moats. The walls have triangular and circular holes used for firing guns and arrows. Openings in the main donjon were used for pouring boiling oil and dropping rocks on attackers. Parts of the moat remain but there is no water.

One look at the castle shows that not all of the features are militaristic. Some are aesthetic. The white plaster walls, curved stone base and straighten edge roof with curved gables were intended to be pleasing to eye.

Image Sources: 1) Illustrations and diagrams, JNTO; 2) Pictures: Ray Kinnane (tea house, small shrines), Visualizing Culture, MIT Education (old village), Nicolas Delerue (modern Traditional house), on mark productions (Torri gates), Japan Visitor (machiya houses).

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated May 2014