CLASSIC 20TH CENTURY JAPANESE LITERATURE

In the 19th century, the Japanese language used in literature and the Japanese used on the streets were almost like two different languages. One of the goals of Meiji era writers was to produce literature that ordinary people could understand.

Acclaimed early 20th century Japanese writers include Soseki Natsume; Ogai Mori; Naoya Shiga; Saneatsu Mushakoji (1885-1976); and Kan Kikuchi (1888-1948). Sakutaro Hagiwara is sometimes called the "father of modern Japanese poetry." A heavy drinker who spent a lot of time with prostitutes, he worked as a juggler and magician before taking up poetry. For much of his life he lived off money given to him by his mother and died at the age of 56. He wrote verse like "gleaning metallic wrists/ pointedly polished/ bind me, rend my flesh/ and chip my bones."

“Nagai Kafu, whose life and work reflected the tension between the modern and a yearning for the old Japan, is best known for his elegiac works. “Bokuto kidan “(1937; “A Strange Tale from East of the River”), a notable example of such fiction, depicts in loving detail a fading demimonde on the outskirts of Tokyo.

Good Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on Osamu Dazai Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Soseki Natsume Wikipedia ; Online Translation of Natsume’s Kokoro eldritchpress.org ; Yasunari Kawabata kirjasto.sci.fi/kawabata ; Nobel Prize Biography of Yasunaria Kawabata nobelprize.org ; Nobel Prize Biography of Kenzaburo Oe nobelprize.org ; Abe Kobo ibiblio.org/abekobo ; Hoshi Shinichi sfwj.or.jp Seu Shonagon infionline.net ; Literature Sites Japanese Literature Home Page www.jlit.net ; History of Japan’s Literature kanzaki.com/jinfo ; Japanese Literatures Resources Page mockingbird.creighton.edu ;

Yukio Mishima Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Blog with video of Mishima’s Last Moments dcaligari.blogspot.com ; Biography kirjasto.sci.fi/mishima ; Yukio Mishima Site dennismichaeliannuzz.tripod.com ; Yukio Mishima Museum mishimayukio.jp/english ; Yukio Mishima's Suicide dennismichaeliannuzz.tripod.com/finalDay ;

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TALE OF GENJI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BASHO, HAIKU AND JAPANESE POETRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC 20TH CENTURY JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN LITERATURE AND BOOKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HARUKI MURAKAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS AND WESTERN WRITERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Modern Literature Begins in the Meiji Period

The imperial restoration of 1868 was followed by the wholesale introduction of Western technology and culture, which largely displaced Chinese culture. As a result, the novel became established as a serious and respected genre of the literature of Japan. A related development was the gradual abandonment of literary language in favor of the usages of colloquial speech. Futabatei Shimei produced what has been called Japan’s first modern novel, “Ukigumo “(1887-1889; “Drifting Clouds”). What is strikingly fresh about the novel is the colloquial style of the language, Futabatei’s conception of his hero’s plight within the context of a quickly changing society, and his subtle psychological examination of his protagonist. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In the 1890s, Futabatei’s psychological insight was adopted by several young writers. One of the most impressive works of fiction in this style was the story “Takekurabe” (1895-1896; “Growing Up”), by Higuchi Ichiyo. In this tale of children living in a red-light district, Ichiyo describes adolescent loneliness and the confusion attending the onset of puberty. Another writer, Shimazaki Toson, relates in his first novel, “Hakai “(1906; “The Broken Commandment”), the story of a schoolteacher who hides the fact that he was born in a community of outcaste people until he realizes his only salvation lies in living openly with the truth. After “Hakai”, however, Toson retreated into his own private world to write in the genre of personal history known as the “I-novel” (“shishosetsu”).

Osamu Dazai

Osamu Dazai (1909-1948) is a popular nihilistic and decadent novelist and essayist much loved by Japanese women. He wrote passionately, drank heavily and committed suicide at the age of 39. The final phrase of his novel “ Tsugaru” is “Why not get along cheerfully? Don’t give into despair. Bye for now.”

Dazai’s writing has been described as delicate and bright even when the writer indulged himself in pessimism and darkness. Dalai was born in Kanagi, a district in the city of Goshogawara in Aomori Prefectur in northern Japan, and wrote eloquently about returning home there. hE was born into a family of wealthy landowners. He grew up in a stately, semi-Western-style mansion surrounded by four-meter-high brick walls. The estate was sold off after World War II, but has been preserved as a museum-cum-monument to Dazai. It is called Shayo-kan after one of his most representative works, "Shayo" (The Setting Sun).

“No Longer Human” is a three-chapter novella that begins with the narrator confessing “I have lead a very shameful life.” He then talks about how he chose to live in isolation at a young age after seeking refuge in alcohol, tobacco, women and radical politics while still in high school and attempting a double suicide with a woman who succeeded while he did not. In the third chapter he gets involved in sex and alcohol again — along with drugs — and ends up in a mental institution after another suicide attempt.

Dazai committed suicide in Tokyo. He drowned himself on his birthday, June 19, 1948 in the Tamagawa Josui canal in Mitaka, with his mistress. The day is remembered as “Oti-ki” (“Cherry Death anniversary”) after his last complete novel “Oto” (“A Cherry”).

The 100th anniversary of Dazai’s birth in 2009 was celebrated with great fanfare in Japan. Some left bottles of sake and cans of beer at his grave in recognition of his love of alcohol. Over a million copies of his books were sold that year. His life has been the subject of a French documentary.

Ryunosuke Akutagawa

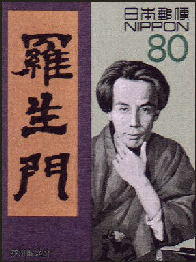

Ryunosuke Akutagawa is regarded as the unofficial “father of the Japanese short story.” He is believed to have written about 100 short stories before he tragically committed suicide at the age of 35. Japan’s most prestigious literary prize is named after him.

Akutagawa’s most famous work is “Rashomon” (1915), a period piece about the rape and murder of an aristocratic women by bandits as seen from four conflicting viewpoints. Made into a famous Akira Kurosawa film, it explores the meaning and perception of truth. “Like Rashomon,” “Yabu no naka” (1922; “In a Grove”) is brilliantly told, combining psychological subtlety and a sardonic tone with a fanciful delight in the grotesque.

“Rashomon” and other stories such as “In the a Bamboo Grove”, “Hell Screen”, “A Spider Thread” and “The Nose” are available in English in “Mandarins” (Archipelago Books, 2007) translated by Charles De Worlf and “Rashomon and 17 Other Stories” (Penguin), translated by Jay Rubin.

Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Spider Story

The “ The Spider Thread “ by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, wrote Kevin Short in the Daily Yomiuri, is story that “starts off with Lord Buddha up in Paradise, looking down into the deepest layers of Hell. There, among the doomed souls choking and floundering in the Pool of Blood and getting flayed to ribbons on the Mountain of Needles, is an evil robber and murderer named Kandata. This incorrigible character had certainly earned several million years' worth of horrible torture and punishment. On one occasion, however, the evil man had shown a small measure of compassion. Walking through a deep wood, he had chosen not to crush the life of a small spider crawling across the path at his feet. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, December 16, 2010]

“Lord Buddha, himself a bundle of super-concentrated compassion, decides that despite his untold number of horrible sins, Kandata should be rewarded for this one good deed. From a nearby celestial spider web he takes a strand of silver thread, which he lowers down into the depths of hell. Kandata seizes the thread and begins climbing upward. But just when it looks like he might make it, he realizes that thousands of other souls are shimmying up behind him. Afraid that the added weight might snap the thread, Kandata yells for the other souls to let go. This selfish act is his undoing, and the thread snaps just above where he clings. Kandata plummets back down into the Pool of Blood.”

“There are two vital messages embedded in this story,” Short wrote. “One is that there are spiders in paradise. If spiders are acceptable, there might also be scorpions, snakes, and other glamorous plants and animals as well. Paradise might not be such a boring place after all. The other vital message is that small kindnesses to tiny creatures, and perhaps general adherence to a nature-friendly land ethic as well, may count as good deeds. For example, I am constantly picking up worms and caterpillars that I find crawling slowly across the road and moving them off into the bushes before they get squashed by a passing car. I am also very diligent about not destroying spider webs.”

Soseki Natsume

Soseki Natsume (1867-1916) is pictured on the 1,000 yen bank note and is regarded as one of Japan's greatest writers. Likable but nihilistic, he was born the year before the Meiji Restoration and wrote some of his best stuff while lying on a tatami mat dying. Although he was influenced greatly by Western culture, he is credited with reviving Japanese culture.

Natsume is regarded as Japan's first true modern writer and a master of Russian-style dark, psychological novels. His characters are introspective and serious. Natsume himself was known as a “hateful old man,” who would not talk to anyone unless they were friends or had been introduced with a formal letter of introduction.

The modern Japanese realistic novel was brought to full maturity by Natsume Soseki. His heroes are usually university-educated men made vulnerable by the new egoism and an overly keen perception of their separation from the rest of the world. Guilt, betrayal, and isolation are for Soseki the inevitable consequences of the liberation of the self and all the uncertainties that have come with the advent of Western culture.

Natsume began his career as an school teacher. When he was in his early 30s he was chosen by the Japanese government to travel to England. He spent two years in London and afterwards lectured at Tokyo University. Natsume suffered repeated nervous breakdowns and did not take up writing until he was 37. He wrote novels, short stories and criticism and completed a novel a year while working for theAsahi Shimbun. He surrounded himself with a group of intellectuals considered so awesome and smart they were called the "mountain range." Ogai Mori was a contemporary of Soseki Natsume.

Natsume's Books

Natsume's early works, such as “I Am a Cat” and “Botchan”, are full of humor, satire and pessimism. In “I Am a Cat”, he uses a housecat scrutinizing the actions of an inept schoolteacher to satirize Japan's superficial stabs at Westernization.

The inevitable consequences of the liberation of the self and all the uncertainties that have come with the advent of Western culture are explored in the novels “Kokoro “(1914; “The Heart”), “Mon “(1910; “The Gate”), and “Kojin “(1912-1913; “The Wayfarer”). Mori Ogai first won acclaim with three romantic short stories set in Germany. The most popular, “Maihime” (1890; “The Dancing Girl”), deals with the doomed love affair of a young Japanese student in Berlin with a German dancer. His most representative late works are fictionalized studies in history and biography, such as the life of an Edo-period doctor presented in “Shibue Chusai “(1916). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Natsume wrote two trilogies. In “Sanshiro, And Then” and “The Gate” he follows the story of a young student from Kyushu who arrives in Tokyo and experiences his first feelings of love and later becomes involved in a complex love triangle. In “Spring Equinox and Beyond, The Wayfarer” and “Kokoro” he uses the format of detective novel to follow a family through the eyes of different narrators.

Natsume on the 1,000 yen banknote

“Kokoro” (“The Heart,” 1914) is considered one of the most important Asian literary works of the 20th century. It is about a lonely intellectual who forms a friendship with a young student and reveals his guilt-ridden past.

In his last novels, Natsume began analyzing himself. In “Grass on the Wayside” he deals with himself as harshly as he did other subjects. His last, longest and most ambition work, “Light and Darkness”, scrutinized a modern marriage and was never finished.

Image Sources: 1), Books, Amazon; 2) Photos, Wikipedia

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012