TATTOOS IN JAPAN

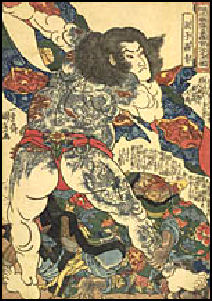

Influenced by traditional wood block printing, “Irezumi” (Japanese-style tattooing) is regarded as folk art like ceramic making or landscape painting. Japanese tattoos are usually made with red and blue natural dyes and often cover the whole body. The elaborate designs often include auspicious symbols, animals, Buddhist deities, or characters from folk tales.

Influenced by traditional wood block printing, “Irezumi” (Japanese-style tattooing) is regarded as folk art like ceramic making or landscape painting. Japanese tattoos are usually made with red and blue natural dyes and often cover the whole body. The elaborate designs often include auspicious symbols, animals, Buddhist deities, or characters from folk tales.

Getting a tattoo in Japan is very expensive and painful, involving pricks and pokes and blood. Hand-tattooing is done with natural colors and tools such as chisels. Machine-fired electric needles are faster and use aniline dyes to produce more intense colors . Photographer Felan, creator of the book “Japanese Tattoo”, describes the appeal of tattoos as "the glorification of the flesh as a means of spirituality," "power bestowed at the price of submission," and "beauty created through brutal means."

Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in Los Angeles Times: “Japanese tattoos are steeped in thousands of years of history and bound by rigid tradition and social mores. This distinguishes them from American tattoos, which are largely personal expressions of individualism. Japanese masters spend years perfecting their craft and learning the stories behind the tattoos, derived from woodblock prints and Chinese folk tales. The body-suit tattoos, spanning shoulders to below the buttocks, can take hundreds of hours to apply and cost as much as $20,000. [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, June 24, 2012]

“Banned during the Meiji period, irezumi (literally "to insert ink") remains underground today; many hot springs and bathhouses still bar tattooed individuals. Artists work under a cloak of secrecy plagued by associations with criminality. Asked what a popular design is today, the tattoo artist Horihide describes the Japanese carp. When caught by a fisherman, the carp does not thrash around like other fish, but remains still, quietly accepting its fate. "So Japanese guys take the spirit of the carp," he explains, "rather than struggle against fate.”

Book: “Bushido, Legacies of the Japanese Tattoo” by Takahiro Kitamura and Katie M. Kitamura (Schiffer Publishing 2000); “The Japanese Tattoo” by Ritchie (Weaterfill, 1980)

History of Tattoos in Japan

Tattooing has a long history in Japan. Tattooed clay figures from the Jomon period (10,000 B.C. to A.D. 300) have been unearthed. Chinese texts from the A.D. 3rd century mention Japanese tattooing. Native Ainu women wore Tattoo mustaches as a sign of virtue.

In feudal times, authorities tattooed criminals so they could be stigmatized by the rest of society. Repeat offenders were given had Chinese characters marked their foreheads that described their crimes. Over the years, outlaw types took pride in these markings as a sign of irreverence and rebellion.

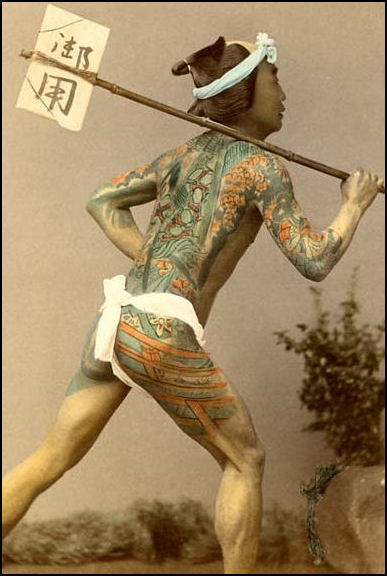

In the Edo period workers in certain professions began wearing a tattoo of their guild mark. In the early 1800s, firemen began the fashion of wearing full body tattoos. If a fireman died in a fire the tattoos helped identify him. The practice was later adopted by gamblers, laborers, sushi chefs and members of the yakuza. Getting tattoos was viewed as a rite of initiation to an exclusive group. Many sushi chefs today have a guild tattoo.

Tattooing was banned in 1872 in the Meiji period as a primitive and backward practice. The ban was not lifted until 1948. Even so in the late 19th century many sailors got tattoos while stopping in Japanese ports. King George V of England became an admirer of the art form when he was a sailor and had a dragon tattooed on his arm there in 1881.

Among some other famous people said to have gotten Japanese tattoos were Russia’s Czar Nicholas II, Queen Olga of Greece and Winston Churchill’s mother.

Full Body Tattoos in Japan

People with full body tattoos are called “horimono”. A body tattoo can cost several tens of thousands of dollars and take years to complete even with biweekly sessions. The designs cover the back, buttocks, and upper leg and are made so that they are kept secret and only revealed when the horimono removes his clothes. Designs on the chest and upper arms are limited so the wearer can unbutton his shirt and roll up his sleeves without revealing his tattoos.

People with full body tattoos are called “horimono”. A body tattoo can cost several tens of thousands of dollars and take years to complete even with biweekly sessions. The designs cover the back, buttocks, and upper leg and are made so that they are kept secret and only revealed when the horimono removes his clothes. Designs on the chest and upper arms are limited so the wearer can unbutton his shirt and roll up his sleeves without revealing his tattoos.

Full body tattoos reportedly began as a way for criminals to hide their criminal brands. The practice was picked up by elite samurai in the 18th century. Full body tattoos are usually made with a particular theme and are influenced by centuries-old Chinese folktales and stories from kabuki and noh theater. Artists often discreetly sign their works.

Tattoos artist generally begin in the middle of the back and expand outward in postcard size blocks. The pain is intense during the sessions, enough to cause nausea and fainting, and can linger for days afterwards. Getting tattoos on the stomach and lower back are particularly painful.

Quietly enduring the pain is part of the ritual. The pain helps establish a bond between the customer and the tattoo artist. There is a tradition of the horimono remaining in touch with the tattoo artist his entire life and seeking them out on occasion for advise on personal matter.

Horimono periodically get together for meeting and opportunities to show off their tattoos to one another. People with tattoo masterpieces sometimes donate their skin to university museums in their wills. Tokyo University reportedly has a collection of 300 framed tattooed skins.

Japanese Hand Tattoo

Reporting from Gifu, Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in Los Angeles Times: “Hidden away in the backroom of a modest apartment in this central Japanese city, one of Japan's last remaining hand-tattoo masters is preparing his tools. Over the last four decades Oguri Kazuo has tattooed notable geisha and countless yakuza, members of Japan's notorious mafia. Today, the 79-year-old artist, known professionally as Horihide (derived from "hori," meaning "to carve"), is working on a client who is a little more subdued. [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, June 24, 2012]

“Motoyama Tetsuro has spent hundreds of dollars, traveled thousands of miles and waited more than three decades for a session with Horihide. The Japanese-born American software manager wanted the master's ink in his skin — a living legacy for a dying art. With old masters passing away and young apprentices lacking the patience to learn the painstaking craft of tebori (hand tattooing), many followers believe its days are numbered.

“If you know the master, why would you want to work with someone else?" asks Motoyama, 62, who first received the outline of a dragon by Horihide on his right shoulder in the 1970s. Motoyama lost touch with the master — who works only by word-of-mouth introductions in backdoor locations — before the work was complete. Last November, after a 30-plus year search, he finally located Horihide and traveled back to Japan from his home in Cupertino, Calif., to finish the piece.

“Pariah status has led to a decline in tattoo masters, with Horihide estimating that there are only five or six left who can do the traditional black-and-white tebori as opposed to the machine-operated colored tattoos. (Horihide offers both.) Social stigma has not put off the soft-spoken Motoyama who, with square glasses and salt-and-pepper hair, appears the epitome of respectability. Although the grandfather is happy to show off his tattoos in California, he, like most, is careful to hide his arms in Japan behind long sleeves despite searing summer temperatures.

“Specializing in tebori is not commonplace," says Kip Fulbeck, an art professor at UC Santa Barbara, who is organizing a 2014 exhibition of Japanese tattoos at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles with tattoo artist Takahiro Kitamura (known as Horitaka). "For one, it takes a great deal of time to traditionally learn how to do it correctly. It's also a much slower tattooing method, so it takes much more time. [Unlike machine tattooing] it's very subtle, it's very quiet." Although Horihide has eight students, none can yet draw their own designs and just a few are learning tebori.

19th century tatooed postman

Life of Japanese Hand Tattoo Artist

Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in Los Angeles Times: “Horihide became an apprentice at age 19 and spent five years learning the craft. "It was very strict. In the morning you have to get up at 5 o'clock and clean the house. If you didn't do it right, you could be beaten," recalls the artist, as he sits cross-legged on the floor, carefully filling in the yellow hues of a tiger on Motoyama's other shoulder. "But nowadays young people can't do that. Some people who want to be students ask me, 'How much can you give me as a salary?'" He laughs, shaking his head. "So things have changed." [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, June 24, 2012]

“As a teenager, Horihide fled to Tokyo after a street gang fight. When money ran out and hunger started to gnaw, he saw a sign offering room and board to a tattoo apprentice. Despite lingering prejudices surrounding the once-forbidden art (the ban was lifted in 1948 by the occupying forces), Horihide carefully practiced on his own skin — scars of now faded squares and circles on his thigh today.

“Past clients were largely the yakuza and an occasional hot spring geisha, who marked themselves with phoenixes, dragons and killer whales. Horihide's memories of the yakuza — who provided generous gifts — remain fond. "Younger people do not know how to be courteous and do not know how to speak to me," he complains.

“Today, however, his clients are largely construction workers and firefighters, members of fraternal organizations who are traditionally tattooed. Motoyama pulls a white T-shirt back over his head and then buttons up a black shirt — carefully hiding both the dragon and newly inked tiger, which still bubbles with small specks of blood. "Today, tattoo artists just use a stencil and copy designs," he says sadly. "With Horihide's designs, every one is unique. [But] in the long run I don't know how long they can survive.”

Tattoos and the Yakuza

Some yakuza members have body tattoos with dragons, carp, Chinese goddesses, and mythic characters of strength. The tattoos are usually located on the backs, shoulders and upper arms, places hidden by clothing. Often the only place where people see the tattoos is at public baths.

Most ordinary Japanese avoid tattoos because of their association with the yakuza and gangsters. People with full body tattoos are often prohibited from entering public baths. Horimono say these associations are unfair. Yes, they say, there is certain amount of machoness associated with full body tattoos and some gangsters have them, but a direct connection between the two comes from formulaic gangster films.

Because tattoos are associated with the yakuza tattoo artists are sometimes called on by police to help solve crimes.

Some yakuza members are spending $25,000 to have their tattoos removed with lasers. One plastic surgeon told the Los Angeles Times, he treated 70 to 80 former yakuza between 1992 and 1997. The majority of those who sought treatment, he said, were gangsters in their 20s and 50s who wanted out of the yakuza.

Some mistresses of yakuza bosses have much of their body covered with tattoos from yakuza mythology.

Osaka Tattoo Ban

In May 2011 the right-wing populist mayor of Osaka, Toru Hashimoto, ordered all government employees to voluntarily divulge any concealed or visible tattoos. The 100 or so discovered to be inked, who mostly work in waste disposal and transport, were told to get rid of the tattoos or at least make sure they are always hidden or face being fired. [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, Los Angeles Times, June 24, 2012]

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Ten employees working at schools run by the Osaka municipal government, including one primary school teacher, have been found to have tattoos, the Osaka municipal board of education revealed. Of the 10, the teacher and another employee were found to have tattoos in places easily seen by students, the board said.At a meeting, the secretariat of the board of education came up with a plan to strictly instruct the 10 to never expose their tattoos to students. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 27, 2012]

“The survey was conducted on about 17,000 staff at municipal government-run education facilities. They voluntarily told principals concerned if they had tattoos. The teacher who admitted to having a tattoo was quoted as saying students could not see the tattoo and the teacher wants to have it removed. The teacher's gender has been withheld for privacy reasons. The remaining nine are not in teaching positions, working in such areas as, maintenance or kitchens, according to the board. The board declined to announce the names of the schools with tattooed staff and where and how big the tattoos are. There were no plans to transfer the staff.

Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto told reporters, "I've heard the teacher [with the tattoo] wants to have it erased, and I hope the teacher has it done in a way that doesn't shame the teaching profession. I believe the board of education, instead of having the tattoo survey conducted by principals, should have carried it out on its own.”

“About 33,500 city government employees, except those in education, underwent earlier tattoo surveys on Hashimoto's instructions. Of them, 113 were found to have tattoos.The city's board of education initially refused to conduct the survey on education facility employees over concerns for their rights. After protests from Osaka residents, who insisted the board of education should not allow education-related employees to be tattooed, the board conducted the survey.

Image Sources: 1) xorsystem blog 2) Hector Garcia 3) Tokyo Pictures 4) and 6) Andrew Gray Photosensibility 7) Japan Visitor, 8) British Museum, 9) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012