URBAN AND RURAL LIFE IN JAPAN

Urban population: 78 percent; rural population: 22 percent. (Compared to 90 percent urban and 10 percent rural in Great Britain and 13 percent urban and 87 percent rural in Ethiopia). At present around 45 percent of the population of Japan is concentrated in three metropolitan areas around Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya.

As part of the effort to reduce the cost of government, the Koizumi administration cut the number of towns and villages in the early 2000s by incorporating small towns and villages into large ones, assuming that spending would be handled more efficiently by larger towns and cities. To get local mayors and council members to vote themselves out of office they were offered generous buy outs.

The recent merger of villages and towns, known as “Heisei no Daigappei” has dramatically reduced the number of municipalities in Japan from 3,231 to 1,821 as of Match 2006. Hundreds of small towns and villages have become parts of big cities.

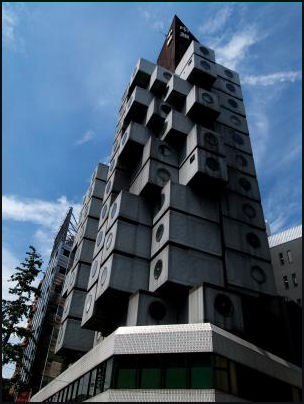

Japan’s tallest skyscraper is the 300-meter-tall Abeno Harukas in Osaka, which as of 2012 was still under construction. In August 2012, the China Daily reported: “The building’s operator, Japan Railway’s Kintetsu Corporation, announced the new 60-story skyscraper set its record by installing an 11-meter steel beam on the top of the building, bringing it over the previous 296-meter tall record. Located in Osaka’s southern commercial district, the new landmark will be in the center of a hub of railway terminals, where Kintetsu lines and others connect. Completion is scheduled for 2014. While not official until then, the Abeno Harukas technically replaced the Yokohama Landmark Tower as the tallest building in Japan. The building will offer a total floor space of over 300,000 square meters, and among the businesses inside will be a museum, hotel, department store, and several restaurants and offices. [Source: Adam Westlake, China Daily, August 31, 2012]

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Rural Life in Japan Blog rural-jp.blogspot.com ; Life in Rural Japan Blog joruraljapan.blogspot.com ; Towns and Villages in Japan ikjeld.com/japannews ; Beautiful Village Contest maff.go.jp/soshiki ; City Life Pictures on Photopass Japan photopassjapan.com ; Google ebook: City Life in Japan (1958) books.google.com/books ; Check Street Photography in Japan Window japanwindow.com/gallery ; Links in this Website: EVERYDAY LIFE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Urban Life in Japan

Many Japanese customs, values and personality traits arise from the fact that Japanese live so close together in such a crowded place. Everyday the Japanese are packed together like sardines on subways and in kitchen-size yakatori bars and sushi restaurants. A dozen lap swimmers may squeeze into single lane at a swimming pool. Bicycles and pedestrians fight for space on crowded sidewalks, which are especially packed on rainy days and sunny days, when umbrellas are out in force. If there weren't such strict rules and strong pressures to obey them people would be all over each other, in each other’s face, and at each other's throats.

In Japanese cities there are recorded messages everywhere telling you what to do: at crosswalks, on buses, on subways. Regular announcements warn subway riders to stand back from the edge of the platform. Sometimes they tell you things like "don't forget your umbrellas," "please refrain form using mobile phones" and "keep the city clean and tidy." There are flagmen for sidewalks near construction sites.

In Japanese cities there are recorded messages everywhere telling you what to do: at crosswalks, on buses, on subways. Regular announcements warn subway riders to stand back from the edge of the platform. Sometimes they tell you things like "don't forget your umbrellas," "please refrain form using mobile phones" and "keep the city clean and tidy." There are flagmen for sidewalks near construction sites.

Japan has managed to keep major department stores and shopping areas downtown rather than relying suburban shopping malls, which have kept downtown alive and prosperous. Urban activity is often concentrated around the train and subway stations.

Japanese cities are very clean. Graffiti is hard to find and when it found it often has an upbeat message like “Find Your Dream.” It is not uncommon to see a uniformed man down on his knees scrapping a wad of gum the pavement or a policeman issue a ticket to someone for smoking on the streets. Even so the number of rats in the cities appears to be on the rise. They have been blamed for starting fires by nibbling through electrical wires and making nests in vending machines. Many of the rats are roof rats which are harder to control than the more common Norway rat.

The volume ratio for high-rise residential building promotion areas was raised, and in measuring the volume ratio for condominiums, steps and halls for common use were dropped from the items to be counted in the volume. This measure substantially increased the volume that could be used for living space itself. A 1998 revision to the Architectural Standards Law permitted designated private organizations to perform building inspections previously performed only by local government bodies. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

In a survey in 2011 by human resources consultant ECA International, Tokyo was listed as the world’s most expensive place to live with a typical two-bedroom apartment renting for $4,352 a month, ahead of Moscow at No. 2 where two-bedroom apartments rented for $3,500 a month. As for 2012, The Guardian reported: “Tokyo has regained the dubious honour of being the world's most expensive city, where a cup of coffee will set you back £5.25, a newspaper £4 and a litre of milk £2. The Japanese capital topped the annual cost-of-living survey by the HR consultants Mercer, which ranks cities according to the needs of expatriates. Luanda, in Angola, where more than half the population of 5 million live in poverty and where the Foreign Office advises visitors not to venture out at night, was the second most expensive. The cheapest city was Karachi, in Pakistan, where the cost of living was a third of that in Tokyo, closely followed by Islamabad. [Source: The Guardian, June 13, 2012]

Ugly Japanese Cities

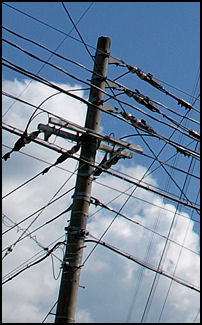

Japanese cities are surprisingly ugly. Buildings are thrown together with no rhyme or reason and cramped together with few or no trees. The roads are very narrow and lined with wire-laden utility poles. Advertisements cover everything.

Alex Kerr, a Kyoto-based writer, wrote that many people are ashamed to live in old houses that foreigners find charming, “Old things are equated with the poor, uncivilized, dark, dirty...lacking in “bunmei” [civilization]...The reality of how people live has almost nothing to do with their traditional culture...The result is that people started to feel that their native culture is irrelevant, useless, behind the times “and they’re embarrassed about it...What happens is that you get a vicious circle. So after a while, when nobody has ever seen a street with trees on it, or buildings that are made out of natural materials, or shopping areas not covered with signs...People are getting in the idea that [this] is progress and is the way a city must look.”

Prof. Yukio Nishimura of Tokyo University’s graduate school of engineering told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Japanese had a sense of aesthetics, of what is ugly and what is not. But after the war, they abandoned this. They had to survive..” He blamed the hodgepodge nature of Japan’s urban neighborhood on affluence and individuality. “It’s like a buying a car. People don’t want to have the same one as others have, so they try to build something different.”

On the issue of why Japanese don’t complain about ugly houses of their neighbors he said, “Japanese art most concerned about things that directly relate to them, but when it comes to something that does not, they are completely uninterested.” A leader of an anti-development group told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “this problem is unique to Japan, because there’s nobody telling these people that it’s just outrageous to put up billboards and signs wherever you want.”

One of the main culprits for Japan’s ugliness is the plethora of utility poles and wires. Unlike most developed cities around the world, where various kinds of cables are kept underground, most Japanese cities have them above ground. The reason for this is that after World War II Japan wanted to bring electricity as quickly as possible to as many people as possible and it was easier and much less expensive and obstructive to do this by putting up utility polls rather than laying cable underground.

In the Tokyo area was a comprehensive plan to bury utility lines under highways and roads but those plans were dealt a crippling blow by the Fukushima nuclear crisis after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami which sucked up funds by Tokyo Electric Co. (TEPCO) earmarked for burying the lines.

Some like Japan’s urban chaos: the rows of neon signs in Ginza in Shibuya; the roads that go through buildings in Osaka and tangle of railway lines that engulf busy train stations.

U.N. Report Names Fukuoka City as Model for Sustainable Growth

In June 2011, Kyodo reported: “ The Japanese city of Fukuoka is a model for sustainable growth in Asia, where many cities will likely face difficulty continuing their rapid economic expansion because of inadequate planning for environmental conservation and the greenhouse effect, according to a U.N. agency report. [Source: Kyodo, June 17, 2011]

In the report presented at the fifth Asia-Pacific Urban Forum in Bangkok, the U.N. Human Settlements Program, or UN-HABITAT, said rapid urbanization will result in the majority of the region's population living in city areas by 2026. About 30 universities in Asia, including Kyushu University, cooperated in compiling the report to survey about 480 cities.

On Fukuoka, where UN-HABITAT maintains a regional office, the report notes that it has all the amenities of a modern urban city and yet traffic congestion is rare. The southwestern Japanese city also maintains a balance between development and environmental conservation, between urban areas and suburbs and between modernity and tradition. Fukuoka also has local agriculture and fisheries industries that can supply fresh food as well as businesses such as animation and robotics that attract young professionals, the report said.

"In the future, Asia will see a rapid increase of cities with around 1 million people," said Toshiyasu Noda, director of the regional office for Asia and the Pacific at UN-HABITAT. "I want to convey the great features of Fukuoka, which is home to about 1.5 million people and has earned a reputation for its quality of life among those in and outside Japan," he said.

Towns and Neighborhoods in Japan

Japanese towns and neighborhoods are very compact. An area that covers only a couple of blocks is often packed with sports stadiums, a variety of schools, office buildings, lower middle-class apartments, rich homes, pachinko parlors, restaurants, parks, playgrounds, busy streets and supermarkets with parking lots on their roof.

Zoning rules seem looser than in the United States. Beauty parlors and shops are often found in houses in residential districts. It is also surprising what can be found in a suburban neighborhood. Superhighways skirt crowded neighborhoods but the highways are so ultra-quiet it is hard to tell they are there.

Japanese addresses are sometimes hard to figure out. Things are organized by areas and zones rather than streets. Japanese often identify places by nearness to a landmark rather than a street number.

Community Life in Japan

Many Japanese urban neighborhoods have a sense of community with a set of mutual rights and obligations that is not unlike that of a rural village. On Sundays, for example, you can see groups of older Japanese men wearing the same hats and jackets cleaning up litter around their apartments. In some places parents are fined if they don't show up at P.T.A. meetings.

“Kairanban” describes a system in which one neighbor delivers a clipboard with various announcements regarding the community and the recipient of the clipboard is expected to pass it on to another neighbor. Each exchange is accompanied by a nice chat and exchange of gossip. A similar system called “renrakumo” is issued to pass on messages from the school to one groups of parents and then another.

Mailboxes are typically filled with advertisement for English lessons, pizza parlors and neighborhood brothels. Door-to-door visitors include condom salesgirls, Buddhist political party canvassers and toilet paper exchangers that exchange rolls of toilet paper for magazines and newspapers.

In the old days rural communities worked together to build bridges, maintain shrines and temples and participated in fire-fighting brigades.

Lots of homeowners stuck far out in the suburbs with long commutes and houses for which they significantly overpaid.

Rural Life in Japan

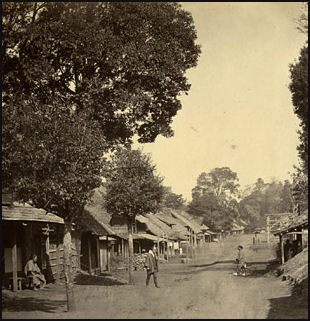

19th century village At the end of World War II, 50 percent of population still lived in rural areas. At that time 36 percent of the farm families owned 90 percent or more of the land. Today 90 percent of the farmland is owned by individual families.

Large parts of Japan are sparsely populated but the places that are inhabitable are so densely populated that even rural towns and villages often seem cramped. Much of rural Japan has a man made-made look. Many rivers are dammed and have cement river banks. Hillsides have been terraced and forests are made of stands of trees, planted by people and all belonging to the same species.

Most rural Japanese don't feel they miss much by living in the cities. A resident in a country town on the west coast of Japan told National Geographic, "I like to go [to Tokyo] a few times a year — I like the shops, and there are friends to see. But I'd never move there. We don't think about it too much over here." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic, September 1994]

Life in the country is very different than life in urban Japan. Families of shop keepers often live above their shops, calculations are sometimes still made on an abacus and the wife often runs upstairs when business is slow to take care of household chores. Post offices serve as banks and insurance companies. Volunteer postmen serve as firefighters, report on potholes and traffic accidents and help out elderly people by picking up their bank books and bringing them back cash. Business in some places is conducted on a barter system known as “dan-dan” (“thanks again”).

The less developed side of Japan that faces the Sea of Japan is often referred as the “backside of Japan” as opposed to more developed “front side” that faces the Pacific.

Book on Japanese rural life: “Haruko's World” (1983) by Gail Lee Bernstein.

Farmers in Japan, See Economcs, Agriculture

Depopulation of Rural Areas in Japan

“Kaso”, or de-population, is a big problem in the rural areas in Japan. Rural communities are shrinking as a result of migration to the cities, declining birth rates that have robbed rural areas of children and the trend for people to loose their bonds to their home towns and live where they please. Increased life spans have meant that the people that remain behind are getting older and older and dying off.

Most young people find small town life boring and are anxious to get out, and migrate to urban areas when they get the chance. In some rural areas, schools built for 400 students have enrollments of 150. The populations of some towns have dropped by 25 percent or more and the remaining residents wouldn't be there without government subsidies.

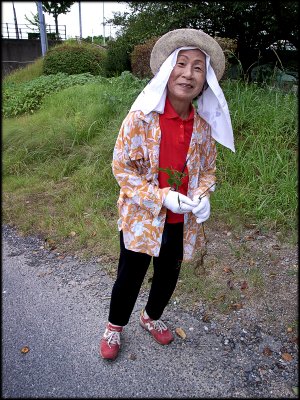

Rural areas are filled with old people. Kaso has caused the median age of Japanese farmers to rise from 42 in 1960 to 60 in 1990. Most of those who have stayed are first sons. In some towns the hospital, school, stores and many homes have been abandoned. The only place that is crowded is the cemetery.

The elderly people that remain are hardy lot who continues to work outside and do many chores by hand.

Disappearing Villages in Japan

Tens of thousands of villages have shrunk to shadows of their former selves. By one count 2,643 communities are considered to be on the brink of disappearing and have bene labeled as “endangered communities.” Another 60,000 are”communities on the edge.”

Between 2000 and 2010 about 200 communities in Japan disappeared. On Hokkaido about 20 percent of small towns and villages are in trouble, with half of them expected to vanish by 2020. Residents of dying towns says that national government does little to help them stay alive other than providing low-interest loans to maintain infrastructure. [Source: Los Angeles Times]

In Hokkaido, one town tried with little success to give away plots of land to people who agreed to move there and register as official residents. Another Hokkaido town put several of its schools for sale on a yahoo auction site, converting one into a nursing home.

Communities are losing their bus services and public transportation because of a lack of passengers. Schools have shut down from a lack of children. Stores have closed. Health care facilities are far away. Farmers find its too expensive to transport their products and stop raising crops. People in their 90s are taken care of by offspring in their seventies.

Some villages are full of abandoned houses. Untended fields cover the site once occupied by a school. The only people in sight are 70 or older. Some of the most endangered villages are former fishing villages that have lost people as the fish stocks have declined. A typical fishing village in Hokkaido has shrunk from 10,000 people to 2,000, with four out of five people being pensioners and one forth over 75.

Many of these communities are situated in the mountains and there are worries about the effect of their deterioration on the environment. Abandoned rice paddies have deprived frogs and fireflies of habitats. Unmaintained forest have led to decreases in timber yields and clouded water in rivers,

Kanna, a once busy agricultural and timber center about three hours northwest of Tokyo, has seen its population drop from 20,000 in the late 1970s to 2,600 today. More than 60 percent of the residents are over 60 and only 80 children attend the two elementary schools and two junior high schools. High school students have to attend school in other places. Most don’t come back. The town has suffered as a result of low timber prices, competition from abroad and large scale farms that undersell them.

The closing of schools ca be a particularly devastating hardship. At one school in Wakayama. Four adults passed an entrance exam for a high school so it have enough students to remain open.

Shopping Refugees in Japan

The closing of shops and stores in mainly rural areas is creating “shopping refugees” who are having trouble buying basic necessities as all the stores near them have closed. Between 2002 and 2009 about 10 percent of Japan’s supermarkets, mostly in rural areas, closed. By one count there are 6 million shopping refugees who face difficulties because of old age and the closure of nearby shops.

The convenience store chain Family Mart has begun opening up small stores with a limited product line to meet the needs of these people. Sapporo-based supermarket chain Seicomart delivers goods to hard-to-reach places in Hokkaido and even delivers goods by boat to people with no access to shops on islands off Hokkaido. In Kumamoto Kengun shopping arcade offers a taxi service for the delivery of goods.

Yubari

Yubari is an infamous town that tried to revitalize itself after a coal mine closed in the 1980s by attempting to turn itself into a tourist attraction by building an expensive amusement park, a robot museum and other poorly thought-out tourist attractions with municipal funds. Few tourists came to the town and the result was huge debts and the bankruptcy of the town.

In the 1960s, Yubari was a prosperous mining town with a population of 120,000. By the early 2000s, it was saddled with $500 million in debts, which worked out to about $40,000 for each of the town’s’s 12,828 inhabitants. In 2006, the local government consolidated 11 schools into four, cut back on snow removal, closed libraries and museums, raised taxes, began charging hefty fees for water and sewage and made other changes to pay back the debts.

About half of the town’s 300 municipal workers were laid off and the those that stayed on had salary cuts of 30 percent to 70 percent. The cuts was so thorough and severe that the toilets in Yubari station were closed, forcing those in need to use a hotel next door, and the hospital-turned clinic could no longer offer things like kidney dialysis, forcing people who needed such treatments to go elsewhere or die. Not making matters any better as Yubari looks ot the future is the fact that 40 percent of the town’s residents are over 65 and 8 percent is under 8, making Yubari the most aged town in Japan.

Experts are watching what is happening in Yubari and see it as test of how much or how little Tokyo will help Yubari out and how the precedent would affect other towns in financial trouble. Many blame Tokyo for creating the situation by giving out too much money and soft loans.

Efforts to Revive Depopulated Towns

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Many settlements away from urban areas have been losing their community functions due to their aging and dwindling populations...Some communities are making efforts to restore or maintain such functions. In the Kumanocho district of Fukuyama, Hiroshima Prefecture, for example, residents have set up a committee to start a grocery store. All the supermarkets and convenience stores once in the area have closed. The committee has secured about 10 million yen to open the shop by attracting subsidies from the municipal government and investments from local residents. It will rent a vacant store for free from a local agricultural cooperative, at which a new 100 yen shop will also be opened. "We'll work together to make our community a better place to live," said Tetsuro Kaita, 80, head of a neighborhood association, emphasizing the word "we." He said residents will take turns working at the new store after it opens. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 3, 2012]

In contrast, the Maruzo district of Hita, Oita Prefecture, is an example of unsuccessful efforts by local residents to revitalize their area. The mountainous district, which used to be part of the village of Nakatsue before it was merged with Hita, had a population of 178 in 79 households as of the end of March 2012, with those aged 65 or older accounting for 58 percent of the total. Residents formed a group called Furusato Mimamori-tai (team to watch for the hometown), with a membership of about 50. People who have left the district have also formed a group called Furusato Oendan (squad to cheer the hometown), whose membership is about 900. Members of the two groups have been engaged in community work, such as mowing grass, planting trees and conducting traditional events.

However, fewer former residents have participated each year, to the point where no former residents helped plant cherry trees in April this year. The residents' group, meanwhile, has suspended publishing newsletters for members of the other group. "The district's population has been steadily decreasing," said Atsumi Furusawa, 59, head of the residents' group. "We're wondering how we can maintain relationships with those living outside our community.”

Nonprofit organizations can work as a bridge between residents in depopulated farming villages and those living in urban areas. In the Masutomi district of what used to be Sutama, Yamanashi Prefecture--now part of the city of Hokuto--once-deserted plots of land have been cultivated by people from outside the district. Among them are members of Egao Tsunagete (connecting smiles), a local nonprofit organization that holds events to facilitate exchanges between the farming village and urban areas. It was set up by Hisashi Sonehara, 50, who moved from Tokyo to what used to be the town of Hakushu, which is now part of Hokuto. Cultivation in Masutomi began in 2003, and the nonprofit organization has turned three hectares of abandoned land into fields and rice paddies. They now attract about 4,000 visitors a year, including volunteers and employees of major companies in Tokyo seeking interaction with nature.

The Nagatani community of Minami-Satsuma, Kagoshima Prefecture, also attracts about 3,000 visitors a year. It has a population of just 23 in 14 households. The average age is 85, with the youngest 55 years old. A local nonprofit organization called Project Minami kara no Kaze (winds from the south) has been playing a leading role in attracting visitors to the tiny community. In 2007, for example, it introduced a measure to invite outsiders to become "owners" of local terraced paddy fields. A kiln and a farmers market have been built with the help of subsidies from the central and prefectural governments, and workshops to make soba and other events have also been held.

The organization's activities have inspired local residents. They have held nearly 100 meetings over the past two years, trying to recreate a framework by which community members help each other. Unfortunately, however, a local primary school will close at the end of March next year. Resident Akira Maruta, 86, pointed out how difficult it is to prevent the local population from shrinking. "It's a desperate issue, how to encourage young people to move here," Maruta said. "Fundamental issues won't be solved unless our community becomes attractive enough for those who used to live here to return home, or even for strangers to relocate here.”

Foreigners Buying up Land in Japan Using Japanese Names

In April 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “At least 1,100 hectares of mountain forest and other land have been acquired by foreigners, with Hokkaido providing the lion's share, according to a Yomiuri Shimbun survey. The survey discovered 63 land transactions involving foreign purchasers, but Japanese names were apparently used to disguise many of the deals, a subterfuge not recognized by local governments. This indicates the number of deals in which Japanese land and forests are falling into foreign hands may be much larger than those found in the survey. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, April 28, 2012]

According to the survey, foreigners bought 57 pieces of land totaling 1,039 hectares in Hokkaido, accounting for 94 percent of land acquired by foreign capital nationwide. Of the purchased land, about 70 percent was obtained by corporate bodies or individuals in Hong Kong, Australia and other places in Asia and Oceania. Corporate bodies in British Virgin Islands, known as a tax haven, were involved in 11 land transactions. Regarding such deals, some people believe water resources are being targeted by foreign buyers.

In one example in which a Japanese name was used to disguise a land transaction, a Chinese in his 40s living in Sapporo bought 14 hectares of mountain forest and other lands near the Niseko area in Hokkaido last autumn. For this transaction, he used the name of a Japanese real estate company. During an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun, the man said he was afraid of provoking a backlash from the Japanese if he bought the land under his name. He also said he hoped to resell the land for a profit as he thought Japanese land prices had bottomed out.

A real estate agency in the Kanto region that was involved in the sale of a mountain forest to a foreign customer said: "Even though foreigners don't aim to obtain water resources, their acquisitions could cause consternation. They feel safe if their deals are registered under a Japanese name.”

Japanese Landowners Seeking Foreign Buyers

In May 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A trading firm based in Otaru, Hokkaido, recently received an e-mail from a Chinese woman saying, "As mountains in Japan are cheap, I'd like to buy one for my child." Hideyuki Ishii, president of Hokkaido Style, said with a smile, "We receive requests like this all the time." The company, which focuses on business with China, started a full-scale land brokerage business for foreigners after company officials noticed that wealthy foreigners visiting Hokkaido to ski snapped up land before returning home--as if they were buying souvenirs. So far, the company has handled land transactions totaling billions of yen. Many of the buyers are Chinese, who are not allowed to own land back home. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, May 10, 2012]

Ishii, 39, believes that many of these land acquisitions are just investments by the wealthy. "Landowners are desperate to find anyone, including foreigners, who will buy their land," he said. "I feel strong demands from landowners is spurring land acquisitions by foreign buyers.” The demand to sell is apparently due to a slumping forest industry and aging landowners.

According to the Japan Real Estate Institute, prices of mountain forests have been declining for 20 years. Last year, the average price of a 1,000-square-meter plot of mountain forest was only 49,288 yen. A 78-year-old man in Otaru who sold mountain forest land to a Chinese buyer last year said: "There's no one to take care of my mountain forests, so the land had been abandoned. I felt it was a waste of money to own land I had to pay property tax for.”

Many people in Hokkaido welcome foreign investment. For example, Hokkaido's Niseko ski and hot spring resort has seen a rapid increase in Australian tourists over the past decade. In the town of Kutchan, which is part of the Niseko resort and has more than 200 vacation houses aimed at wealthy foreigners, the rate of increase in land prices was the nation's highest for three consecutive years until 2008.

U-Turners Who Return to the Countryside in Japan

middle class home with

rice field in the back yard In the 1990s, there was an exodus of people moving from the cities to the countryside. People who were brought up in the country, worked in the cities and then returned to their homes were called the "U-turners." Those who started in the country and then moved to a different rural area after getting fed up with urban life were called "J-turners." And people who were brought up in the cities and moved to the country after college were called "I-turners."

One U-tuner, a former coffeehouse manager who now runs an onion farm, told National Geographic, "I have a steady income, not too many financial worries. My life now is tiring, but psychologically it does me good. The pace is very slow. I see things clearly. I ride my bike an hour and a half to work in the morning, and I can pay attention to the value of nature. And it’s the best environment for my daughter." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic September 1994]

Another man told National Geographic: "A small but growing minority of Japanese would like to unplug themselves from the giant economic machine and the conformist social system behind it. I used to call Matsushita employees 'industrial refugees'’people who suffered a lot and weren't doing what they wanted. Money? I'm broke. But money has no value. To live is the value. I eat what I grow. You can live without money?I'm proving it." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic September 1994]

To offset de-population, local officials in fishing villages are trying to lure new fisherman from the cities with promises of free boats and Filipino wives. Small towns are creating "technopolises" to attract workers to the low-stress country life, building townhouse complexes with incredibly cheap rent, and running lotteries that give out free land to people who are willing to build a house and live in it for 20 years. [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic, September 1994]

These day many U-turners are retired people or middle-aged company employees who have tired of city life and/or the rate race. Government programs offer training courses for people from the cities who want to move to the countryside to practice farming.

Exodus of Women from Rural Areas in Japan

The countryside is full of single men because few women want to marry farmers or endure the drudgery of rural life. "Wives here are wanted primarily for their labor," one rural Japanese woman told the Los Angeles Times. "That is why is no Japanese women want to do it. Japanese women have better options." One said that in his town only five out of 30 girls in his school class stayed to marry men in his hometown.

The traditional Japanese rural wife is often expected to fulfil the wishes of not only of her husband but also of her husband's parents. The traditional selfless wife, o-yome-san, is expected to raise her children, help in the fields, and take care of her mother and father in law. She is expected to be the first up in the morning and the last one to bed at night and never complain about the chores.

Arranged Marriages for Japanese Farmers

Many single rural men choose poor women from the Philippines, Thailand, Korea, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, China and even Brazil and Peru as their wives from pictures in catalogs. "I realized that if I didn't get a bride from Thailand," one farmer told the Los Angeles Times, "I would probably spend the rest of my life alone."

The men usually pay marriage brokers around $25,000, who make the arrangements and work out the details, and travel to home country of the women, who invariable can't speak Japanese. If the couple likes each other, the Japanese man often gives her family some money (up to $30,000) and she returns with him.

The success of the marriages between farmers and foreign women has been hit or miss. The New York Times described a Filipino marriage partner who so impressed her Japanese community with her positive attitude that another local farmer married her sister. The Los Angeles Times described brides hounded by in-laws for a male heirs and farmers who were dumped by their wives soon after they arrived in Japan so they could seek higher paying jobs in the city. It is reported that of the eight marriages with foreign brides in the town of Tadami, two ended in divorce and two more were reportedly in trouble.

There is also local help for farmers in the countryside that are having a hard time finding wives. There are wife-seeking trips to Osaka and Tokyo for these farmers.

In 1995, there were more than 20,000 marriages between Japanese men and foreign women. This figure represented about 2.5 percent of all marriages and was a tenfold increase from 1970. A large number of the men were farmers with mail-order brides.

Image Sources: Ray Kinnane except old village (Visualizing Culture, MIT Education)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013