HOMES IN JAPAN

According to a 1993 study about 62 percent of all homes in Japan were owned by their residents (about the same number as in the United States) and 46 percent of homes were built of timber, 31 percent of fire-proof timber, and 22.5 percent of concrete or other non-timber materials. Many Japanese pay only 2.5 percent interest on their mortgages.

The average living space in Japan has increased from 70 square meters in 1973 to 94 square meters in 2003. An average dwelling in Tokyo has 3.9 rooms and 66.8 square meters of floor space. An average dwelling in rural Japan has 4.7 rooms and 111.67 square meters of floor space.

Many families live in apartments. Urban and suburban houses are packed close together and have some sort of fence to ensure privacy.

Japanese spend significantly more time outside their homes than Americans. Their homes have traditionally been very cramped and chaotic. Japanese are used to living in small spaces, in many cases surrounded by clutter.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: ROOMS AND APPLIANCES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TOILETS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Japanese Houses on KidsWeb web-japan.org/kidsweb ; About Homes csuohio.edu/class ;Traditional Japanese Design eastwindinc.com ; Businessweek Piece on Micro Homes images.businessweek.com ; Japanese Design japanesehomeandbath.com ;Statistical Handbook of Japan Housing Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; Traditional Japan, Key Aspects of Japan japanlink.co ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles with a section on traditional houses (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese) shirofan.com ; Modern House Designs trendir.com/house-design ; Good Construction Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de

Sites for Expats Japanable site for Expats japanable.com ; That’s Japan thats-japan.com ; Orient Expat Japan orientexpat.com/japan-expat ;Kimi Information Center kimiwillbe.com ;Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report on Japan fco.gov.uk/en/travel-and-living-abroad ; Student Guide to Japan www2.jasso.go.jp/study ; Japan in Your Palm japaninyourpalm.com

Thatch Roof Houses of the Shokawa Valley Websites: Shirakawa Grasso Houses shirakawa-go.org/english ; Japan Guide japan-guide JNTO article JNTO Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO UNESCO World Heritage site UNESCO Utsukushi-ga-Hara Open Air Museum Website: JNTO article JNTO

Renting and Buying a Home in Japan

Renting an apartment in Japan requires a lot of money up front. One typically has to pay a couple months deposit, plus key money (a unreturnable “gift” to the landlord). Landlords also require a guarantee who promises to pay the rent if a tenant defaults. Housing costs — determined by how much space you get for the money — are on average at least double that of the United States.

Buying a home is often not a very good investment in Japan. Their value doesn’t go up; many houses are constructed to last only 15 or 20 years; and houses are difficult to sell. The government offers mortgages deductions and tax breaks on new houses that are not offered to second and third time owners. Only 11 percent of home sales are for pre-owned houses compared to 76 percent in the United States.

The bubble economy hurt many salarymen who bought their dream homes in the suburbs. Some took out large loans only to watch the value of their home decline in the 1990s while they endured long commutes to their jobs and had to make mortgage payments at Bubble economy levels.

The New York Times talked to one Tokyo city bureaucrat who bought a cramped four-room apartment in the suburb for $400,000, using a loan to pay for almost the entire thing. By 2005 the apartment was worth only $200,000 and he still owed the bank $300,000

Some Japanese have spent $250,000 on a house only to find unsound foundations, tilting floors and rotten floorboards. In some cases houses are worth less than zero when you figure in the $10,000 cost of tearing a house down and carting it away. Some homeowners get into deep financial trouble, Unlike the United States where homeowners can turn over the keys to the bank, Japanese don’t have that option and required to pay the full amount.

Expensive Property in Japan

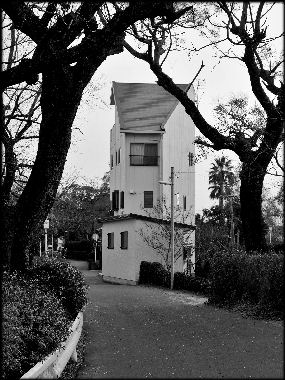

A really thin house Most expensive cities for expatriates according to the 2008 Mercer Cost of Living survey: 1) Moscow; 2) Tokyo; 3) London; 4) Oslo; 5) Seoul. According to a survey by ECA International Tokyo is the most expensive city

Average annual rental prices per square foot for a top-end office space in 2006:1) West End, London, $212; 2) Central Tokyo, $146; 3) The City, London, $145; 4) Outer Central Tokyo, $134: 5) Hong Kong, $116; 6) Moscow, $109; 7) Mumbai, $106; 8) Paris, $106.

Most expensive cities in the world based on two room apartments in a good neighborhood (1999): 1) London ($2.05 million); 2) Tokyo ($1.76 million); 3) Hong Kong ($1.68 million); 4) Paris ($1.67 million); 5) Sydney ($1.3 million); 6) New York ($1.25 million); 7) Stockholm ($1.47 million); 8) Zurich ($1.13 million); 9) Chicago ($1.04 million); and 10) San Francisco ($1 million).

At the height of the bubble economy in the 1980s all the property in Japan, which is smaller than California, was worth five times that of the United States. According to the Guinness Book of Records, the land in central Tokyo around the Mediya Building was the most expensive in the world ever. In October 1988 the Japanese National Land Agency estimated its value at $248,000 a square foot. Mediya is a retail food store. The grounds of the Imperial Palace in downtown Tokyo was said to be worth all the land in California. Australia sold part of the land its embassy was on and paid off half of its foreign debt.

Land prices in central Tokyo are going up while those in smaller cities is decreasing. The price for one square meter of and in Marunoucho ward in central Tokyo is 107 time higher than a quare meter of land on the city of Maebashi.

Housing prices are so astronomical high partly because government regulations and tax laws that discourage an active property market.

Making the Most of Tight Spaces in Japan

"Foreigners are amazed by the smaller scale of things" in Japan, William Bodiford, a UCLA professor of Asian languages and culture, told the Los Angeles Times. "Natives get used to negotiating tighter spaces. They're raised to be very aware of one another, notice their surroundings." Such spatial negotiation doesn't come easily. "It took me a long time to realize why I felt so clumsy in Japan and not nearly so in America," Bodiford said. "The desks and ceilings are lower, the spaces cramped. It's so much easier to bump into things."

The Japanese are very good at using small amounts of space. “ Mottainai “ is a Japanese word that means a wasteful use of space. Even the rich have to design their dream houses to fit on small plots of land. The $6 million house of Mine Ryuta, a well-known host on Japanese television, stands on a quiet street, in a neighborhood in Tokyo known for its expensive ryotei restaurants. The land in which the house stands covers only 400 square meters, or 4,305 square feet, which is large by Tokyo standards. [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, June 17, 2010]

Miki Tanikawa wrote in New York Times, “When you set foot on the grass roof of it feels like you have landed on a small planet. Much of the house was designed around the pool, with several rooms opening directly onto the area...The house itself, a three-story building in the Kagurazaka section of central Tokyo, is not the normal Japanese home. It looks like a flying fortress straight out of Hayao Miyazaki’s fanciful animation, or a beached submarine, complete with portholes for windows.”

“When we first sat down with the architect, my wife said she wanted a pool in the house,” Mine told the New York Times. “We also had to have a garage large enough to accommodate our five cars,” a collection that includes a Bentley and a Porsche. The answer became an enclosed parking area that wraps around the back of the house’s ground-level entrance. “Putting the garage at the back, that was the genius of the designer,” Mr. Mine said. The house was created by Yokogawa Architects & Engineers of Tokyo.

“The house’s entry level includes Mr. Mine’s office and a meeting room that offers a broad view of the shiny cars lined up behind,” wrote Tanikawa. “As a visitor goes upstairs, the living space expands and the outdoor swimming pool comes into view. Putting the 15-meter-long pool upstairs was a structural challenge that delayed construction by three months...The rest of the floor contains the master bedroom and bathroom and a small gym where Mr. Mine works out daily. There also is a sitting room with a view of the pool, a Japanese style guest room and a mirrored studio that Mrs. Mine uses for aerobic exercise.”

“At the top of the 200-square-meter house there is a living room, kitchen and three bedrooms “ one for Mrs. Mine; one for their son, Kei; and one for their daughter, Ubu. Ubu shares her mother’s love of Americana, a major theme in the house’s decoration, and has installed a pole in her bedroom for pole-dancing exercise. As for the roof, the couple’s pair of Brussels Griffon pups...enjoy running around on the grass. But the planting also has another purpose.” “The grass and the earth beneath it make the entire house warmer,” said Mr. Mine. “We only need floor heating during winter to warm the house up.”

Microhouses and the Squeezing of Japan’s Middle Class

Reporting from Osaka,Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “ Like many members of Japan’s middle class, Masato Y. enjoyed a level of affluence two decades ago that was the envy of the world. Masato, a small-business owner, bought a $500,000 condominium, vacationed in Hawaii and drove a late-model Mercedes. But his living standards slowly crumbled along with Japan’s overall economy. First, he was forced to reduce trips abroad and then eliminate them. Then he traded the Mercedes for a cheaper domestic model. Last year, he sold his condo “ for a third of what he paid for it, and for less than what he still owed on the mortgage he took out 17 years ago.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, October 16, 2010]

“Japan used to be so flashy and upbeat, but now everyone must live in a dark and subdued way,” Masato, 49, told the New York Times. He asked that his full name not be used because he still cannot repay the $110,000 that he owes on the mortgage. He sold his four-bedroom condo to a relative for about $185,000, 15 years after buying it for a bit more than $500,000. He said he was still deliberating about whether to expunge the $110,000 he still owed his bank by declaring personal bankruptcy.

“The downsizing of Japan’s ambitions can be seen on the streets of Tokyo, where concrete “microhouses” have become popular among younger Japanese who cannot afford even the famously cramped housing of their parents, or lack the job security to take out a traditional multidecade loan,” Fackler wrote. “These matchbox-size homes stand on plots of land barely large enough to park a sport utility vehicle, yet have three stories of closet-size bedrooms, suitcase-size closets and a tiny kitchen that properly belongs on a submarine.” “This is how to own a house even when you are uneasy about the future,” said Kimiyo Kondo, general manager at Zaus, a Tokyo-based company that builds microhouses.”

For many people under 40, it is hard to grasp just how far this is from the 1980s, when a mighty “ and threatening “ ”Japan Inc.” seemed ready to obliterate whole American industries, from automakers to supercomputers...As living standards in this still wealthy nation slowly erode, a new frugality is apparent among a generation of young Japanese, who have known nothing but economic stagnation and deflation. They refuse to buy big-ticket items like cars or televisions, and fewer choose to study abroad in America.”

Waterfront House Wedged on a Tiny Piece of Land in Kobe

Miki Tanikawa wrote in the New York Times, “ Ryosuke and Yasuko Uenishi took on a difficult challenge in 2003 when they spotted a small parcel of 130 square meters that stuck out as a kind of terrace from an embankment in the Shioya section of Kobe. The couple thought it might be suitable for a scenic house that would meet their budget of ¥20 million.” “We were told, “No structure has ever gone up here because it was small and narrow,” Uenishi told the New York Times. “But the price was good so we bought it with cash.” [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, October 14, 2010]

The couple suffered a major set back when their application for a building loan was abruptly turned down. “The loan officer told us, “That’s not land,” “ Mr. Uenishi said. But when Shuhei Endo, the architect whom the Uenishis had approached, published a design for the site in a book, the bank changed its mind. “Suddenly, it was a land,” Mr. Uenishi said.

“The steel-frame house, completed in 2004, offers 69 square meters of living space, stretched over two levels,” Tanikawa wrote. “The lower floor houses the bedroom and the bathroom. The triangular main floor, which is at street level, is narrow near the entrance, where the kitchen and dining area are located, and widens into the living room. The living room view is as beautiful as it is busy : there are two railroad tracks, a major road, the ocean corridor occupied with ships and small craft, and airplanes filling the sky from nearby Kobe airport. Isn’t the house noisy?” “We had to get used to it,” Mrs. Uenishi said. “It took three months of getting used to.”

Tadao Ando’s 4-x-4 House in Kobe

Designing the 4x4 House on the outskirts of Kobe confronted many physical and manmade challenges “Whenever I have a project where I have to work hard to overcome physical limitations, it often ends up winning reactions from all over the place,” Ando told the New York Times.”From an architectural design point of view, no one would be interested in houses that were designed and built luxuriously using millions of dollars.” [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, October 14, 2010]

The 4x4 project began with Yoshinari Nakata’s property, about 65 square meters, or 700 square feet, squeezed between the railroad tracks that run along the Kobe mountain range and Suma beach. About a quarter of the lot is regularly under water, “so the land I could use to build a structure was very limited,” Mr. Nakata said. He responded to a magazine solicitation that invited readers to apply for an opportunity to have a house designed by a noted architect.

Mr. Ando, one of the participating designers, was interested in the site’s limitations, and the fact that the property is near the seismic center of the 1995 Hanshin earthquake that killed thousands. The epicenter was on Awaji Island, just across the Akashi Strait. “I wanted that house to be a point of remembrance for the earthquake,” he said.

Design of Tadao Ando’s 4-x-4 House in Kobe

Miki Tanikawa wrote in the New York Times: “Drawing on his flair for geometric designs and cast-in-place concrete, Mr. Ando proposed a unusual design: the fourth floor pops out about a meter toward the water from the rest of the rectangular structure.” “It’s a small space that subsumes a much larger space,” Mr. Ando said of the effect. [Source: Miki Tanikawa, New York Times, October 14, 2010]

The house’s living room, kitchen and dining area all are there within the four-meter by four-meter footprint “ hence the house’s nickname. Whenever he is on the fourth floor, Mr. Nakata said, “I feel like I am on a boat, floating about in the ocean.” “Here, the ocean view comes to you,” he added. “You don’t have to take a look through the window.” There is a lot to look at, including Awaji Island and in the distance, the Akashi Strait Suspension Bridge, which at 3.9 kilometers, or about 2.5 miles, is the longest span of its kind. Tankers and cruise ships pass by often and, below, children often play along the beach.

Bedrooms are on the house’s third floor, a study on the second, and the bathroom and storage space on the first. Mr. Nakata, who lives in the house with his wife and 3-year-old son, said the building cost was ¥35 million, or about $427,000 at today’s exchange rate. It was finished in 2003. But one drawback is that the trip to the toilet from the living room involves three flights of stairs. “My wife often complains about the ups and downs involved, especially when she has to bring the groceries up to the kitchen after shopping,” Mr. Nakata said. But he added: “The view is so precious. I would miss it if I lose this.”

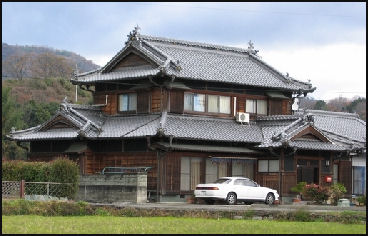

Traditional Japanese Homes

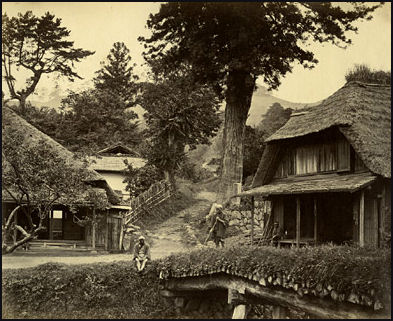

rural house in the 19th century Influenced by Zen Buddhism, the traditional Japanese home is simple and austere yet elegant. Common features include a fluid floor plan created by movable screens and the use of indigenous woods, straw, bamboo and paper. Large homes have courtyards surrounded by walls for privacy and protection against the prying eyes of tax collectors.

Types of traditional homes include thatched minka houses, samurai residences, teahouses, townhouses, traditional inns, mountain refuges and Haokone retreats. Kuri are traditional storehouses. The are recognizable by their thick white plaster walls. which were designed to protect the valuable supplies inside from fires.

Unique styles of Japanese architecture took shape in the Heian Period (794-1185). The mansions and homes built during this period had elaborate receiving rooms, sculptured gardens with huts, and thatch roofs with Japanese cypress tree beams resting on wooden pillars and beams. The interior had wooden floors with fixed room dividers. Single-leaf and folding screens, tatami and other light materials made it possible to define the living space freely.

The traditional Japanese house as we know it today has its origins in homes of rich farmers in the early Edo Period (1603-1868) and were built with tools and methods imported from Korea and China for building palaces and temples. The interior had wooden floors with fixed room dividers.

In urban areas, the Japanese fascination with the new and the urge to redevelop wins out over efforts to preserve the old. Many traditional houses have been lost because their owners couldn’t pay inheritance taxes — which can be as high as 75 percent of the value of the property — and were forced to sell.

Books: “The Japanese House: Architecture and Interiors” by Noboru Murata and Alexandra Black (Tuttle, 2001); “Japanese Homes and Lifestyles: An Illustrated Journey Through History” by Kazuya Inaba and Shigenobu Nakayama (Kodansha International, 2000)

Thatch-Roof Houses and Machiya Houses in Japan

machiya house The charming-looking, giant, multi-storied, thatch-roof minka farmhouses are designed on utilitarian principals for large extended families with 40 or more people living on the top floors, domestic animals kept on the bottom floor and mulberry-leave-munching silkworms housed in the upper gables. Heat and light are supplied by a fire made in a central fireplace in the floor known as a “irori”. A lack of windows and a lot of make the interior resemble a cave. The best place to see traditional thatched-roof homes is Shirakawamura. The thatched-roof houses there are called gassho-zukuti, which refers to the fact they look like praying arms.

Built through a communal effort, gassho-zukuti are usually made of unpainted boards and waddle-and-daub walls without using a single nail. The steep praying-hands roof are designed the way they area or shed the heavy snows that fall on them in the winter. The name also indicates how devout the local people are. Most are followers of the Jodoshinshu sect of Buddhism.

The thatched roofs can be up to a meter thick and are made hand woven from thick reeds that come from communal grasslands. They are woven into matts that are tied on to the beams of the house by straw ropes. No nails are used. Inside the houses it is very dark. The roofs extend almost all the way to the ground and windows are only at the front and back of the houses. The large houses are four stories high and included spaces for raising silk worms.

The thatched roofs are replaced every 30 or 40 years, with work usually being done in April. The work has to be done quickly so the house is not damaged by rain. As many as 500 people take part in replacing a single roof. Some people stand on the roof beams and put the thatch in place while others hand the thatch up to them. With so much labor involved, the cost of doing a single roof can be $200,000. About three or four houses are reroofed every year, with the generous Japanese government absorbing of the costs.

In the old days villager maintained communal grasslands by annual cutting and burning to provide grass for roofs. The communal grasslands that supply the thatch are disappearing. Many have been plowed over for farms. The roofs and warehouses provide a habitat for raccoons, tanukis, rat snakes, geckos and lizards.

Traditional wooden townhouses found in Gion and elsewhere in Kyoto are called machiya. A typical one is six meters wide and 30 meters deep, has six tatami mat rooms, and is worth about $420,000. Many have lattice windows, stripped beams, Older unrestored ones have dirt floors and mushikomado windows framed by thick clay. They are designed to let cool breezes in during the summer. Today there are only 30,000 of them left (compared to 600,000 modern homes). Many were built in merchants in the Edo period. Today, preservationists are trying to keep these from being turn down.

Most machiya houses have two stories, tiled roofs, and a main entrance that faces the street. The first floor is topped by a small quasi roof that sticks outwards towards the street, unifying the structure with the street and other machiya houses. The first floor windows that face the street are covered by a wooden lattice that make it difficult to see inside and look outside. “Insect cage’ windows” were common on the second story. In the old days dirt floors were the norm in the kitchen area with opening in the roof to allow smoke from cooking fires to escape. Bedrooms and sitting rooms were on platforms elevated from the dirt are and had tatami mat floors. Machiya houses in Kyoto feature decorated fronts and zashiki reception areas with prized folding screens and art pieces.

Features of a Traditional Japanese Home

A traditional Japanese house today is made of wood and has “tatami” mat floors (floor coverings made of two-inch thick pressed straw, covered panels of tightly woven reeds), sliding shoji doors, wooden walls, lacquer doors, clay walls, coffered ceiling, sliding doors, a tile roof, lath-and-plaster walls, wood or metal rain shudders, and “tokonama” (display alcoves).

A traditional Japanese house today is made of wood and has “tatami” mat floors (floor coverings made of two-inch thick pressed straw, covered panels of tightly woven reeds), sliding shoji doors, wooden walls, lacquer doors, clay walls, coffered ceiling, sliding doors, a tile roof, lath-and-plaster walls, wood or metal rain shudders, and “tokonama” (display alcoves).

The Japanese invented sliding doors and sliding walls. Traditional houses have heavy paper sliding partitions that separate one room from another and can be pushed wide open or removed to create a single large room. Some homes have thick winter walls are can be replaced with thin summer ones. Windows facing the outside are often glazed and have grills and curtains so people can't see in

Traditional Japanese homes have multipurpose, easy-to-change rooms. Bedrooms are easily converted to sitting rooms and play rooms and visa versa. Common Japanese tools include a nata, a wonderfully functional Japanese tool--sort of like a cross between a long-bladed hatchet and a heavy fish cleaver, and a kama--a short, single-hand sickle, for cutting heavy brush, and a short-handled bamboo rake. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri]

The “tokonoma” is an alcove in a traditional Japanese home intended for displaying a flower arrangement, a work of Zen-style art or a calligraphy scroll. Many modern homes are built without a tokonoma. The “genkan” is the traditional threshold, entrance area, where people leave their shoes.

Many homes have small Shinto and Buddhists altars. On visiting a Japanese home, one of the first things a host or hostess often does is show their guests pictures of living family members and dead ancestors on the Buddhist altar that is often in or near the tokonama.

The Japanese traditionally would speak to guests in the entrance hall or else show them to a reception hall or living-room-dining-room area. It very unusual for a visitor to come in the kitchen or the bedrooms and have a look around the house.

Many traditional Japanese homes have “shoji” (sliding paper screens) instead of walls. One Japanese artist told National Geographic that shoji creates a "good feeling" because "behind the shoji screen we cannot really see you, but we can know your actions, whether or not your are lively." Shoji windows infuse traditional homes with a soft natural light. "The best condition of paper is between eye and light," one papermaker said. "I can feel the life of the fiber. I can hear it. Perhaps we respond because of our own veins and arteries. We are knitted and connected, like the fiber."

Four-Hundred-Year-Old Nunnery Converted into a House

Describing a 400-year-old nunnery in a Kyoto suburb renovated into a house by the American writer Alex Kerr, Liza Foreman wrote in the New York Times: Entering the house through its old wooden door, a visitor walks on tatami mats through a small entrance room. To the right is the living room, decorated sparingly with a couple of low Chinese hardwood tables, a large rug and several antique screens along the walls, including one by the Edo-era calligrapher Ike no Taiga (1723--76) and one by the Confucian scholar Kan Chazan (1748--1827). [Source: Liza Foreman, New York Times, January 6, 2011]

“One screen hides the entrance to the bedroom, filled with a vast bed, books piled around the edges, and a neatly packed row of screens stored to the side. In the 1980s the doma, a mud-floored room to the left of the entrance room, was turned into a kitchen. It has both a wellhead and a modern sink, a long bench-like table that Mr. Kerr uses as a home office, and many large cupboards, one of which is filled with art supplies.” “Depending on the season or visitors, I change the screens or the scroll. In nooks in the kitchen I keep tea bowls, lacquer trays, brushes for writing calligraphy and so forth. Otherwise, there’s just open space and the garden,” said Mr. Kerr.

The kitchen’s 6-meter, or more than 19-foot, high ceiling first came visible when Mr. Kerr and his friends cleared away decades of soot. Now a pair of wooden eyes taken from a Thai boat hang up there, watching over the room. At the back of the kitchen, a gray steppingstone leads to a modern bathroom. “From the point of view of traditional Chinese and Japanese “literati,” the house has the perfect balance between city and country,” said Mr. Kerr. “I like the feel of old worn wood that comes from hundreds of years of history. Especially I love the slightly unkempt garden with its trees and plants that change with each season.”

Modern Apartments and Middle Class Homes in Japan

Many Japanese live in apartments known as mansions. A typical Tokyo family of four lives in a $300,000 apartment that is about the size of a one bedroom apartment in the United States. It has a living room, dining-room-kitchen, two bedrooms and a separate bathroom and toilet crammed onto 1,200 square feet.

Some apartments are so small that families usually meet and entertain their friends outside the home at a restaurant or other public place because there is no room in their apartment. When a phone rings or doorbell sounds, residents often have difficulty discerning whether its is theirs or their neighbors.[Source: National Geographic]

When you are walking on the street or through an old neighborhoods you often see plastic water bottles set up around a pole or along a wall for no apparent reason. They are usually there to keep dogs from peeing.

There are 2.2 million public apartment units in Japan. Many companies have dormitories, one- bedroom apartment or small apartments for families where the employees can live cheaply. Secure high-rise urban apartments — known as urban castles — are becoming more and more common in Tokyo. In some cases the security is so tight the managers that guard the self-locking doors at the entrances won’t let in local community representatives or even the police.

A typical 75-square-meter apartment in a nine-floor concrete mansion (apartment building) in Shinjuku, Tokyo bought in the mid 2000s for the equivalent of $500,000 has a 375-square-foot, balcony, two bedrooms; one bathroom, which features one of the high-tech toilets with a heated seat so beloved by the Japanese; and some interesting double-paned doors. The lower half of the glass doors are glazed, harking back to a time when the Japanese routinely sat on the floor and wanted a bit of privacy. [Source: Liza Foreman, New York Times, November 26, 2010]

New middle-class houses are increasingly Westernized. Traditional entrances and alcoves and small tatami mat rooms have been replaced large open-plan kitchens and living rooms. Some houses have yards that are so small the grass is cut with scissors. Houses and apartments often lack insulation, which means they are cold and don’t block out the noise of neighbors.

High-Tech Homes in Japan

There are presently houses that have watering systems for plants that are activated by cell phone and covers for drying clothes that emerge when sensors detect rain. Rooms light up, and are cooled or heated when the people enter. Movement is detected by infrared detectors in the ceiling. Video cameras show what is going on outside the house. Singing mailboxes let people know when mail has arrived.

Matsushita is working on developing an automated kitchen on which people can chose a menu, order the ingredients and send instructions through the Internet on how to prepare it with a microwave.

To make interior spaces brighter and more appealing, a Japanese company invented a mirror system with light tracking censors that reflects 70 to 90 percent of the light from the sun into a building There are controls which allow the homeowner to regulate the amount infrared and ultraviolet light that is let in. A home system cost between $14,000 and $28,000 installed. [Source: Leonard Cohen, Discover magazine, June 1988. Cohen has written a book called "283 useful Ideas from Japan]

In 2005, Yamaha introduced 27-square-foot, soundproof, shed-like structure called MyRoom that is intended to be set up in houses to give its occupants some privacy in a crowded home. As it stands now you often see salarymen relaxing in their cars in isolated areas presumably for the same reason.

Energy Efficient Homes in Japan

Only 10 percent of new houses built every year in Japan meet the latest and strictest standards for energy efficiency. Only four percent of all houses in Japan meet the criteria. Such houses use 33 percent to 44 percent less energy than those that don’t meet the standards. Stimulus measures to get people to make their homes more energy efficient have not been widely utilized. [Source: Hiroko Kono, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 2010]

Some have proposed offering better subsidies to people for making their houses more energy efficient. Offering incentives to homeowners to add thermal insulation in their walls and ceilings and install double-glazed window glass would not only reduce energy cost but also be a boost for producers of such products as well as the construction industry, which is suffering as real estate prices decline and money is being taken out of public works projects. A plan for such measured was approved by the Japanese government in June 2010.

Daiwa Smart Homes that went on sale in 2010 are outfit with solar panels, lithium ion batteries, advanced computer systems that controls lighting and other functions and devices that allow system within the homes to be altered from instructions sent by a cell phone or computer. The house has sensors that can turn off a television when someone leaves the room and turn on the water for a bath with an mobile phone or e-mail messag. The system can also turn on the air conditioning or open windows when temperatures get too high.

Hotels and Guest Houses in Japan

Hotel rooms in Japan tend to be small but cleverly designed. Bathrooms often have sinks and bathes served by the same faucet and beds sometimes combined with a desk and night table.

Some traditional Japanese inns are not very welcoming to foreign visitors. This is not necessarily because they are prejudice against foreigners but more often because they worry that foreigner will not follow the proper etiquette and they might argue over the bill because they are not familiar with the Japanese pricing system, particularly the fact that guests pay on a per person basis rather than a per room basis.

“ Ryokan” are the most common kind of traditional Japanese inn found in Japan. Many are found in hot spring resorts. “ Ryo” means travel, “ kan” means inn. A Ryokan is an authentic Japanese-style hotel where long-held traditions are still observed. At the entrance, a woman welcomes the guests in a Japanese way and usher them in. Shoes are removed and slippers are put on before stepping on the tatami (woven mat) floor. Guests are also provided with a yukata, a kimono-like outer garment, and geta, wooden clogs used for walking outdoors.

Each traditional Japanese-style room has a paper sliding door. During the day the room serves as a living and dining room, while at night, it is transformed in a bedroom with a futon (Japanese-style bed). Meals are typically Japanese and dishes such as tempura, sashimi, raw fish and baked fish are usually offered. Soft drinks, sake and other alcoholic drinks are also usually available.

“Minshuku” is the Japanese equivalent of a guest house or bed and breakfast. Most are run by families who rent rooms out their own home and have an atmosphere like that of a home. Guests, for example, are expected to fold up their bedding and put it away in the closet. Minshuku generally cost about US$50 to $1000 a night per night, and includes two family cooked meals. Sometimes in the countryside foreigners are told they are not welcome at the minshukus because they are too big for the baths, rooms, futons and yukatas.

Minshuku meals are served at a fixed time, generally around 7:30 or 8:00am and 6:00pm., and tend to be tasty and filling set meals rather than something ordered from a menu. A typical dinner consists of miso soup, soba noodles, mountains vegetables, egg custard, rice and main dish such as nabe (stew), river trout or even wild boar. Sometimes the breakfast is remarkably similar to the dinner except a fried egg is added.

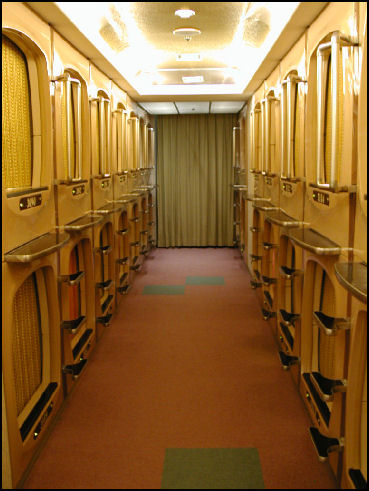

Capsule Hotels in Japan

Japan is famous of its capsule hotels, where salarymen spend the night in coffin-size bed capsules, equipped with bed, television and stereo. The capsules look sort of like the plastic cages used by animals on airline flights and are piled one on top of another and arranged in rows sort of like a morgue.

A typical large capsule occupies three floors of a multistory building and contains a bath house, a 24-hour cafeteria, and a couple hundred capsules. Made of molded plastic and stacked two high, the capsules are about six feet long, three feet wide, and three feet high. They are entered at one end like a cave. The opening is covered by a pull-down rattan blind.

Capsule hotels are sometimes called "silkworm beds" or "drunkard housing." The first one opened in Osaka in 1979 using modified plastic boxes invented by a sauna operator for overnight guests who wanted privacy. The largest one is the 660-capsule Green Plaza Shinjuku in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo. Airport “cabin” hotels at Gatwick Airport in London are modeled after Japanese capsule hotels.

Capsule Hotel Customs in Japan

Capsule hotels are more busy on the weekdays than weekends. Many of the customers are businessman, too drunk, too tired to endure the train ride home, or who have spent too much time in the bars and pachinko parlors and missed the trains home.

Capsule hotels are used mostly by business people in a tight budget who find paying ¥4,000 for capsule more attractive than ¥7,000 for a room in a business hotel, the next cheapest accommodation alternative. Some businessmen are given enough money in their expense accounts for a business hotel and pocket the difference.

Describing a capsule hotel in Shinjuku in Tokyo, Michael Finkel wrote in the New York Times, "The first floor of the five-story building housed a pachinko parlor; the second, a night club. At the third floor, the elevator opened onto the reception area...A middle-aged man was stationed at a desk in front of a block of cubbies that contained footwear."

After handing over ¥4,000 Finkel was told to strip. "And so there, at the front desk, I removed my clothing until I was down to my briefs. Whereupon I was handed a light-blue robe, a pair of white slippers and a mustard-colored towel...The undressing policy...forces a degree of casualness and relaxation, and the same time, maintains a sense of sartorial similarity."

Sleeping in a Capsule Hotel in Japan

After bathing in a bath house, packed with naked salarymen, Finkel entered his capsule. "A small television was mounted on the ceiling of the capsule: two of the three channels were dedicated to pornographic offerings. There was also a radio, an alarm clock, a reading light (with a dimmer switch, a mirro...and an airplane-style air nozzle."

"Sleep did not come easily...just as I'd begun to dream, the first alarm went off, somewhere down the hallway. It was an ear-shattering, air-raid siren of a noise that bolted me upright, causing me to knock my head on the capsule's ceiling. It was 5 o'clock in the morning. No sooner had I realized what had happened and settled back under my sheet than another alarm sounded. And another. And then another — every few minutes.”

Many capsule hotels offer "cabins" with enough space for a small desk. They cost about ¥1,500 more than a capsule. In Osaka there are also nap hotels, where salarymen spend between $4.30 and $11.60 an hour to take a nap inside a tent in a room with 10 tents.

Shared Accommodation in Japan

In March 2011,according to an article in the Yomiuri Shimbun, 27-year-old Rei Matsumoto was looking for a room to rent in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture, a city adjacent to Tokyo, after coming to the capital from Oita Prefecture to work at an acoustic design company. Ultimately she found a vacant room at a shared accommodation in a wholesale district in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo. Residents share a kitchen, living rooms and other communal rooms on the building's first and second floor, and have individual rooms on the third to sixth floors. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 11, 2011]

People who want to eat meals ask other residents whether they want to eat together before going shopping and share the cost. In late December, Matsumoto enjoyed having one-pot meals in the living room with other residents many times, and felt she was not only sharing the accommodation but also sharing happiness with other residents. "If I want to be alone, I can just shut myself up in my room. Here I can connect with other people from an ideal distance," she said.

Tokyo-based Hituji Real Estate operates an online real estate service introducing shared accommodations. The company said as of December 2011, about 1,000 accommodations had registered on the company's website, increasing by more than 250 from the same period last year and more than tenfold from five years ago.

Group Housing Japanese-Style

Sachio Tanaka wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “In spring 2011, Share Residence Ichikawa. an apartment complex with a large common room, opened to tenants in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture, after being renovated from a four-story corporate dormitory. The building has 50 units, most of which are 6.5 tatami-mat rooms, and the first floor has a 100-square-meter living and kitchen space that is used by all residents. [Source: Sachio Tanaka, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 28, 2012]

Most of the tenants of Share Residence Ichikawa are in their 20s to early 40s. Residents are about evenly split between men and women, while 20 percent are non-Japanese. Residents stand side by side to cook breakfast and dinner in the communal kitchen--chatting and sharing food. A bulletin board has a poster reading, "Let's have a barbecue party!" The common area also has a music studio equipped with guitars and drums. The rent, including a common service charge, starts from 60,000 yen, about the same as other apartments in the area.

"I decided to move into this building because I can practice guitar here," said graduate student Shunsaku Kobayashi, 22, who moved in this spring from a regular rental apartment nearby. "I can play music with other residents, and I've become friends with many people who are older than me.”

The number of share house apartments has grown recently, with the units popular among people who want to preserve their privacy but still be able to communicate with other residents in the shared kitchen and living room. The common areas vary from house to house, with some set up to attract music lovers and others made to be accessible to people with disabilities. Share houses are usually buildings similar to those containing regular apartments or condominiums, but some are in free-standing houses. Residents sleep in rooms that can be locked, but often eat and socialize in the shared living room and kitchen. This kind of housing arrangement lets people retain the privacy of living alone while at the same time helping them make more personal connections. Many share-house dwellers are young and single.

Daisuke Kitagawa runs the website Hituji Real Estate, which offers information on share houses. Kitagawa says at least 1,150 buildings and 16,000 houses are run according to the share-house style. Share housing has become a popular niche market, especially in urban areas. Residents are sometimes given a free hand to remodel the common areas. Some have a library feel with many books and photo albums, while others that have pool tables seem more like game rooms. Recently, some share houses have been established to bring together young people interested in agriculture. Residents of these places cultivate vegetables in common gardens. "Until recently, single people in their 20s and 30s cared more about privacy and tended to live alone. But recently, the fun of having a roommate has been getting another look," Kitagawa said.

Share houses are also playing a role in the social welfare field. Paretto, a nonprofit organization that supports disabled people, opened share house Ikotto two years ago in Ebisu, Tokyo. Two mentally disabled women and four unimpaired men live together in the three-story wooden house. On weekdays, the residents have different schedules, but they occasionally share dinner together on weekends. "I've been learning piano recently, and my five housemates came to my recital. Moving into this house has allowed me to feel the joy of interacting with others for the first time," said one resident, a female company employee in her 30s.

The share-house system has also been used as a halfway point for people released from foster homes to help them transition to independence. The nonprofit organization Bridge for Smile rented a new house in Tokyo in April and remodeled it into a share house for six people. Currently, an 18-year-old women who recently left such a home and is now attending a vocational school shares the space with a 34-year-old female company employee who gives her advice on housekeeping and her social life.

Vacant Houses Serve as a Retreat for for City Dwellers

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Surrounded by lush greenery, people ate and drank under the eaves of a house in Okutama, Tokyo. Although I'd assumed they were locals, I learned they were visitors from wards in central Tokyo, including Minato and Meguro. Just a two-minute walk from Hatonosu Station on the JR Ome Line, the house, called "nosnos," is actually a holiday accommodation shared among paying members. [Source: Shuhei Yokoyama, Yomiuri Shimbun, June 2012]

The dwelling has become a popular spot for people seeking a little quiet time on their weekends and other days off, away from the hustle and bustle of city life. The visitors spend their time in various ways. Some sit on the veranda to soak in the terrific view of the mountains in the area, while others find relaxation in reading or taking a nap.

Kazutoshi Sugawara, 24, started the "shared village service" after visiting the area for many years as a student. Wondering how he could make use of the 300 vacant houses in the town, he came up with the idea of providing central Tokyoites a place to call their second home.

Sugawara now heads AtmanZ Co., which offers the shared village service. Membership is 60,000 yen a year, or 25,000 yen for three months. Members can stay in the house for 500 yen per night anytime they want, and take part in local festivals and events. Visitor Saeka Noguchi, 26, said with a smile, "Here, surrounded by nature, I can spend a relaxing time, which I can't get in a busy urban area.”

Image Sources: 1) Ray Kinnane (most pictures) 2) Nicolas Delerue (traditional wood houses), 3) Japan Visitor (machiya house), 4) Stange and Funny in Japan blog (capsule hotel), 5) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education (19th century houses)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013