SUICIDES IN JAPAN

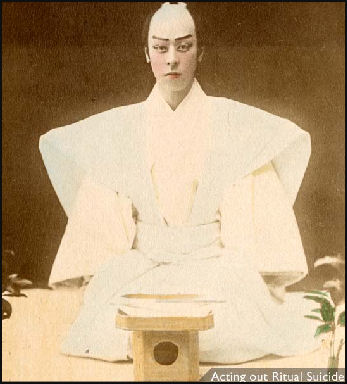

19th century kabuki take

on seppuku The Japanese word for suicide is “ji-satsu” which literally means “kill oneself.” Japan has one of the highest suicide rates in the developed world. According to the World Health Organization, 23.8 Japanese out every 100,000 commit suicide every year, double the rate in the United States, two and half times higher than Singapore or Hong Kong and four times higher than Britain. In the Group of Eight, only Russia has a higher suicide rate (39.4 suicides per 100,000 people).

In 2011, the number of people who committed suicide in Japan was 30,513 according to the health ministry. The NPA reported the total number of suicides in Japan exceeded 30,000 for 14 consecutive years up to 2011, though the number declined by 1,039, or 3.3 percent, to 30,651 from the previous year. Of the total, the number of males who killed themselves decreased by 1,328 to 20,955 from the previous year, and the number of females increased by 289 to 9,696. The number of female suicides exceeded 30 percent of the total for the first time since 1997. By age, suicide victims in their 60s numbered 5,547 and formed the largest group among all age brackets, though the figure was down 6.1 percent from the previous year. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 10, 2012]

In 2009, the number of suicides was 32,753, the fifth highest of all time, an increase of 1.6 percent from the previous year. The number of suicides among people in their 30s (29.8 percent of the year’s total) and over 60 (36.6 percent of the year’s total) reached record high in 2007. Many over 60 committed suicide because they were lonely. Many of those in their 30s were fatigued from work. The number of suicides in 2010 dropped 3.5 percent to 31,690. That year work-related suicides reached an all-time high and the number of people who committed suicide because they couldn’t find jobs increased 19.8 percent .

Of the 32,552 suicide victims in 2005 a total of 23,540 were men and 9,012 were women. Many of the women were over 60. Many of the men were in their 50s or 60 and older. So many men have committed suicide that fatherless children has become a national phenomena.

Over the years there were dramatic increases in rate of suicides among teenagers, young women, men in their 20s and men over 40. A total of 886 students committed suicide in 2006.

In 2003, there was a record 34,427 suicides. This works out to almost 90 a day. Common suicide methods include jumping in front of trains, leaping from buildings, hanging oneself, and carbon monoxide poisoning. More than 40 percent of suicide attempts that result in emergency room visits are repeat attempts by people who tried to commit suicide before.

According to the Japanese health ministry, suicide and depression coast the Japanese economy ¥2.7 trillion in 2009 due to lost income from death and social security payments for depression. Suicide is the leading cause of death among Japanese men ages 20 to 44 and women ages 15 to 34. If a train is late in Tokyo more often than not it is because of a suicide rather than a mechanical problem or accident.

In May 2012, Jiji Press reported; Nearly 30 percent of Japanese aged in their 20s have seriously considered committing suicide, a government survey revealed. The figure was 28.4 percent, up 3.8 percentage points from the previous poll in February 2008 and higher than any other age group, according to the Cabinet Office survey. By age, 27.3 percent of respondents in their 40s said they have seriously considered killing themselves, followed by 25.7 percent in their 50s, 25 percent in their 30s, 20.4 percent in their 60s and 15.7 percent in their 70s. [Jiji Press, May. 4, 2012]

Good Websites and Sources: Academic Article on Social Problems in Japan anthropoetics.ucla.edu ; eclip5e.visual-assault.org ; New York Times article on Hikikomori nytimes.com ; Suicides in 2009 Japan Today ;

Seppuku, Ritual Suicide Wikipedia article on Seppuku Wikipedia ; Seppuku Ritual Suicide fortunecity.com ; Seppuku “ A Practical Guide kyushu.com/gleaner

Links in this Website: JAPANESE SOCIETY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; RICH IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POOR IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ELDERLY IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PENSIONS, NEGLECT AND PROBLEMS FOR ELDERLY JAPANESE Factsanddetails.com/Japan TAXES, WELFARE AND SOCIAL SECURITY IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Suicide and Culture

Suicide does not have the stigma attached to it that it does in Western societies. In fact it has traditionally been an honorable way to resolve problems. Every year there are stories about executives and celebrities who commit suicide (See Mishima, Literature; Hide, Pop Music; and the Tampopo director, Film). Double suicides are a fixture of kabuki and bunraku puppet theater. There are favorite suicide spots like the Aokigahara woods near Mt. Fuji (See Mt. Fuji, Tokyo Area Places).

John Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Japan's view of taking one's own life does not carry the connotations of sin or mental illness that it does in the West. For centuries, the country has maintained a romanticized notion of the noble suicide, fueled by tales of samurai warriors and World War II kamikaze pilots. In 2007, after a Japanese Cabinet minister hanged himself with a dog leash while under investigation in for a series of political scandals, a national politician remarked that the minister "was a true samurai" because he had taken his life to preserve his honor.”

"There's something like 11 different cultural classifications for suicide in Japan; for the most part, there remains some sympathy for the act," said Gaithri Fernando, an assistant professor of psychology at Cal State Los Angeles who has conducted research on how culture affects a person's response to trauma. He told the Los Angeles Times, “"More than half the suicides each year are due to financial reasons, to win back collateral that friends and family had put on the line. It's become a macabre way to pay your debts."

Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky wrote on Atlantic Wire: Suicide in Japan has a long tradition of being a means of apology, protest, means of taking revenge, and dealing with illness. Suicide in Japan does not have the same nuance it does in the West. It’s not a religious taboo. The Japanese have a curious history of finding beauty in the act of suicide. Taking one’s life is sometimes considered more heroic than defeat. [Source: Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky, Atlantic Wire, September 10, 2012]

Novels, movies and the spread of the Internet suicide chat rooms have contributed to the suicide boom in Japan. They have also popularized some areas as suicide landmarks. A forest near the Mount Fuji became the ideal site for committing suicide when a 1960s novel by Seicho- Matsumoto was published. The novel tells a story of a couple who meets their end in Aokigahara forest. Others attribute an increase in the number of suicides to Wataru Tsurumi’s description of Jukai (the ocean of trees) as “the perfect place to die” in his 1993 perennial best-selling book The Complete Manual of Suicide. Both books are reportedly often found along with human remains in the forest.

The manual of suicide seems to have been written in a way to “encourage” readers to choose an easy way of getting rid of problems. “If your children have a copy of that book in their room, you should be aware that something might be going wrong in his life, and do everything possible to prevent suicide by detecting early signs of suicide,” says Duignan.

Seppuku (Hari Kari) and Suicide and History in Japan

“Seppuku” (hari kari) is a form of ritual suicide. A samurai that for any reason dishonored himself or his lord was required to commit “seppuku” by thrusting the knife into his stomach, twisting it and making a slash across the stomach. While he did this an attendant or another samurai loped of his head with a sword.

”Junshi” (literally “following one’s lord”) described the killing ritual in which the stomach was cut from left to right, with an excruciatingly painful crosswise stroke, followed by the swordsman impaling oneself on one’s sword. Many who did this read death poems as they killed themselves. The practice was outlawed by the forth Tokugawa shogun in 1663 because too many samurai were being lost. Twenty six retainers of daimyo Nabeshima Katsushige followed him to death in 1657.

In 1868. Japanese soldiers at Sakai near Osaka killed 11 French sailors. Twenty of the attackers were supposed to commit seppuku as punishment. The French found the spectacle so horrific to watch the ritual was stopped at the 11th one. The nine survivors demanded to die.

In 1912, General Maresukae Nogi famously marked the death of Emperor Meiji by committing seppaku. His wife, apparently willingly, plunged a dagger into her heart. In 1877 Nogi had asked the Emperor for permission to commit seppaku following his regiment’s defeat in the Satsuma Rebellion and the loss of the Emperor’s banner to the enemy. He was crushed when his request was turned down, expressing his feelings a poem that went: “My self is nothing but a person scared of death.” He made the request for seppaku again in 1905 after losing two sons in the war and again was turned down. The state propaganda machine seized upon his successful suicide as the ultimate act of self-sacrifice for the emperor and was used for propaganda purposes to aid the rise of the military. A number of writers wrote about the event.

A 16-year-old Japanese once committed seppuku at a railway station by plunging a 30 inch sword into his abdomen. Two hundred people saw him commit the ritual suicide in which he ripped off the top of his school uniform before disemboweling himself. The boy was rushed to the hospital but died from loss of blood.

Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky wrote on Atlantic Wire: Tadahiro Matsushita, the Minister of Financial Services, was found dead on World Suicide Prevention Day...He allegedly hung himself in his own home. According to Jiji News and other sources, the weekly magazine Shukan Shincho, was getting ready to print a story involving Matsushita and an affair involving a woman. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda said, according to Reuters, "I'm shocked to hear the sad news. He always gave me encouragement when things were tough.”[Source: Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky, Atlantic Wire, September 10, 2012]

Book: “Suicidal Honor” by Doris G. Bargen (University of Hawaii Press, 2004)

Reasons for Suicides in Japan

The reasons behind the suicide in 2009 — determined by either a suicide note or discussions with people close to the victims — was figured out in 74 percent of cases. Many were attributed to job loss and personal hardship. Depression topped the list of reason for suicides (7.1 percent of cases). The number of suicides grew quickly after the Lehman Brothers collapse in October 2008.

In data that the NPA keeps on reason for suicides, 50 different reasons are listed with up to three reasons listed for each suicide. Of the 10,466 people that left suicide notes in 2006, 41.5 percent cited health problems, 28.8 percent cited economic or livelihood difficulties, 10 percent blamed family problems, 6.8 percent cited work problems, 2.8 percent blamed male and female relationships, 9 percent school problems, 6.2 percent others and 3.2 percent not known.

According to one government survey one out of five Japanese adults have seriously considered suicide. Of the 2,207 work-related suicides 30 percent were associated with fatigue, 23 percent with office relationship, 17 percent for mistakes made at work, 12 percent because of changing work conditions and 18 percent other.

Others were young men who were pessimist bout their future. Teenagers sometimes commit suicide after failing their college entrance exams or buckled under stress of school life, high pressure studying and bullying.

The breakdown of the family and loneliness caused by urbanization are seen as root causes. The lack of help sources for those considering suicide, communication breakdowns within families and the stigma attached to seeking help from counselors, psychiatrist and psychologist is also believed to be factors.

Tojinbo Cliff, a scenic spot on the Japan Sea, is another popular suicide spot. One man who has devoted himself to convincing people not to take their lives told Time that potential suicide victims usually come on nice sunny says but “they don’t carry a camera or a souvenir gifts. They don’t have anything, They hang their heads and stare at the ground.”

Among the reasons given for 22,581 people committing suicide in 2011, the largest portion, 14,621, or 65 percent, left indications that they had killed themselves due to health problems. The reasons were found in suicide notes or other evidence. Those who committed suicide because of economic problems totaled 6,406, those who did so due to domestic problems numbered 4,547. School issues accounted for 429 cases, according to the NPA. Meanwhile, 56 people killed themselves for reasons related to the Great East Japan Earthquake in the period from June 2011 through January this year, according to the Cabinet Office. Regarding reasons for the disaster-related suicides, health issues and economic woes were cited as the main reasons for 16 victims respectively. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 10, 2012]

Suicides and Life Insurance Payouts

Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky wrote on Atlantic Wire: Rene Duignan, director of the documentary Saving 10,000: Winning a War on Suicide in Japan, poses a very good question: “Why is it that life insurance companies pay out on suicide? Stop paying people to kill themselves. Stop incentivizing people to die and leave their families alone.”Etsuji Okamoto, a researcher at the Japanese Institute of Health, makes the same arguments convincingly in his 2010 essay "Suicide and Life Insurance."[Source: Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky, Atlantic Wire, September 10, 2012]

In post-war Japan, people would sign a life insurance contract. And go straight out, and kill themselves under the nearest train. Eventually, the life insurance companies started putting in one-year exemption clauses in their policies, so people would sign a contract and they must wait one year before killing themselves to get the money. It was still a very good deal for desperate people, so the suicide rate spiked on the thirteenth month. The insurance companies extended the exemption period to two years. The result was that suicides spiked on the twenty-fifth month of the contract.

Insurance agencies and the police say some men laid off from jobs have killed themselves to enable their families to live in comfort. “Japan has no law mandating how insurance companies deal with policy holders' suicides,” said Masaru Tanabe, spokesman for the Life Insurance Association of Japan famously told the Associated Press in 1999. In March 2004, the Japanese Supreme Court ruled that insurers “must pay for suicides” if the death occurs within the terms of the insurance agreement.

The simple truth is the insured kill themselves for the sake of their family or to pay off their debts.

Suicide and Economics in Japan

in the 1970s, 80s and early and mid 1990s the suicide rate was between 20,000 and 25,000 a year, then it suddenly jumped more by than 8,000 to over 30,000 in 1998.

The jump in 1998 was tied to economic problems. In 1997 a number of financial institutions collapsed. In 1998, the unemployment rate exceeded 4 percent and the filing of personal bankruptcy exceeded 100,000 for the first time. Fluctuations in the suicide rate and unemployment rate have coincided since the 1970s. In the late 1990s the introduction of performance-based salary systems produced higher unemployment rates and coincided with high suicide rates.

Debt and economic troubles were blamed for the death about 8,500 people in 2000, a fourfold increase from a decade earlier. Many victims had gotten into trouble with debt collectors or people that owned companies that went bankrupt. With Japan’s finance laws, when a company goes bankrupt, individuals who own it are deemed responsible and they go bankrupt too.

Many others were men who have lost the jobs to restructuring. The rise in suicides has closely mirrored the rise in the rise in unemployment. Many unemployed victims are not only depressed about losing their jobs and not having money but also depressed by the shame unemployment causes.

One survey in 2003 found that suicide rates are highest among unemployed men. Almost half of suicide victims are men of working age, many of them unemployed. About a forth killed themselves because of “economic and livelihood problems.” A large number also kill themselves to escape heavy debts.

An upturn in the economy in the mid 2000s did not seem to have much affect in the suicide rate. Rates decreases some after 2003 but not by much.

In March 2004, the Japanese Supreme Court ruled that insurers “must pay for suicides” if the death occurs within the terms of the insurance agreement. Sometimes after suicides landlords and real estate agents demand excessive compensation from families of the victims in the grounds that the suicides will make it hard to for landlords to find new renters for the apartments where the suicides took place. An organization for families of suicide victims has received a number of complaints of such harassment. The family of one 30-something company employee who committed suicide said the landlord of the victims apartment demanded $25,000 to renovate the apartment and $60,000 for projected loses in being unable to rent the apartment.

A study by the Japanese government found that suicides are most likely to happen on Mondays, the first and last days of the months and in March, at the end of the Japanese fiscal year. Many of the March suicides are "responsibility-driven" suicides by people hoping to make up for outstanding debts through a life insurance payout, experts told the Los Angeles Times.

Railway Suicides in Japan

Suicides were responsible for more than half of the 40,600 train service suspensions or delays in the Tokyo metropolitan area in 2008, when 307 people took their lives by leaping in front of trains according to the Japanese government transport ministry. At total 228 people killed themselves by jumping in front of trains run East Japan Railway alone in 1998 (196 died in the same system in 2000). One section of JR East Chuo Line has been the site of so many deaths the train that runs it is known as the suicide express.

It is not uncommon for commuter trains to be delayed by a suicide. Typically a suicide begins with a thump and an announcement that there has been a "human incident." Then there is usually an hour-long delay while the mess is cleaned up, the site is photographed and a quick investigation is done.

Families of the deceased have to pay for the damages caused by the suicides, which can to add up to as much as $65,000. JR East reportedly is popular with suicide victims because it charges bereaved families less than other railroad lines.

Leaping to one’s death in front of a train or from a building tend to done more impulsively than other forms of suicide. In an effort to reduce the number of suicides, JR East has installed fences and video cameras at popular suicide spots and painted the crossing at these spots bright colors, which some psychologists believe discourages people at the moment they decide to kill themselves. The train company has also installed mirrors at stations and bright lights triggered by sensors near the edge of the platform under the belief that would-be jumpers are less likely to jump if they can see themselves doing it or have bright lights shined on them.

In some places signs have been put up informing those contemplating suicide that the compensation demanded by train companies for disruptions caused by the suicide can bankrupt their families. Posted on the signs are telephone numbers that people can call for help.

In February 2007, a policeman died after stepping on the track at Tokiwadai Station in Tokyo to rescue a woman who was trying to commit suicide. Both the policeman and the woman were struck by an express train traveling at full speed. Both were trapped underneath the train for about 50 minutes while being rescued. The woman survived. The policemen died after being taken to the hospital.

Jumping Off Buildings in Japan

Actress Fumie Kusayanagi

jumped to her death

from this building A large number of people commit suicide by leaping from buildings. In 2004 two naked “Westerners” died after leaping of the 47th floor of a hotel in Shinjuku.

In August 2003, a 14-year-old boy and 14-year-old girl leaped off an 11-story building in apparent suicide pact. They boy died and girl survived. The teens took off their shoes before they leaped to their death,

Occasionally bystanders on the ground die after being hit by people jumping off buildings. The same day the naked Westerns died, a 29-year-old man died while chatting with a friend after he got hot by a 30-year-old unemployed jumper in Hyogo Prefecture.

In November 2007, a women in her 20s leapt to her death from the roof of a department store in Tokyo’s busy Ikebukuri district In the process of killing herself she landed on a 38-year-old father of two, taking a stroll on his day off, and knocked him unconscious. He never regained consciousness and died in a hospital several days later.

In Tokyo at least two people died and four others were injured by people leaping to their deaths from buildings between 2003 and 2007. In October 2007, a women in her 30s or 40s leapt to her death from a 13-story apartment building store in Minato Ward in Tokyo, seriously injuring a 47-year-old man on the ground, In December 2004, a 42-year-old woman jumped to her death from a building in Musashimurayam, Tokyo and killed a 54-year-old man. In October 2006, a 55-year-old woman leapt tp her death from building in Chofu, Tokyo seriously injuring a female student.

Family and Children Suicides in Japan

A total of 72 children died in 1998 as a result of “ikka shinju”, family suicides. In one incident a 27-year-old man loaded his wife, 6-year-old twins and young son into a the car and told them they were going to their grandparents house. The man had other ideas. He drove the car to an industrial area and drove off a pier into a bay. A fisherman saw the three children clawing at the windows and yelling for help before the care went under.

In July 2007, a 27-year-old woman jumped off a platform in front of a train holding her two daughters. All were killed. In December 2008 a family of five was found dead in a car in a riverbed in Natori, Myagi Prefecture in an apparent group suicide.

Less than two percent of suicides are by minors. In the old days many of these were blamed on “examination hell.” Today many are blamed on bullying. These perception are based more on media reports than empirical evidence.

See Bullying Suicides

Hydrogen Sulfide and Toxic Vomit

In 2008 there were several suicides caused by people making homemade toxic hydrogen sulfide gas by mixing a type of detergent with acid and a bath power with sulfur, cooking it to produce a yellowish smoke and inhaling it in a locked room. Instructions on how to make the gas were posted on online.

The method is dangerous because the gas can spread and easily effect innocent people. It can also cause serious brain damage to survivors. In some cases relatives have either died or become sickened from the gas as they tried to help the suicide victim.

In May 2008, 54 people were sickened by the toxic vomit of a man who attempted suicide by swallowing a pesticide. The vomit released a toxin vaporized from of the pesticide into the hospital where the man was treated. The 54 included doctors, nurses, patients at the hospital, two one-year-old babies and two three-year-old toddlers. Most complained of pain in their eyes and throat. One 72-year-old woman suffered breathing difficulties and was in serious condition.

The suicide victim vomited while having his stomach pumped. The pesticide he swallowed was chloropicrin, a substance designated as a toxic under law. Among those hospitalized were the victims wife and mother rand the doctor that treated him. The victim died. The woman in serious condition was about 10 meters away. She was in the hospital for treatment for pneumonia and kidney failure.

Record High for Youth Suicides in 2011

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: The number of students who committed suicide in Japan in 2011 hit a record figure of 1,029, up 101 cases or 10.9 percent from the previous year, the National Police Agency said. It was the first time that the number exceeded 1,000 since the NPA started recording statistics in 1978. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 10, 2012]

Of the students, the number of university students who killed themselves rose by 16 to 529 from the previous year while the number of high school students who did so increased by 65 to 269, according to the NPA. The combined figures accounted for about 80 percent of the total number of students who committed suicide. By age group, the number of people 19 or younger who committed suicide rose by 12.7 percent to 622 from the previous year, and the figure for those in their 20s increased by 2 percent to 3,302.

Of the students who killed themselves in 2011, 140 committed suicide due to academic underachievement and 136 did so due to worries about their future after leaving school, the NPA said.

Faked Suicides and Assisted Suicide

In 2010, the Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s largest paper reported that police conducted autopsies in only 4.4 percent of the cases determined to be suicides the year before. The lack of proper autopsies was only brought to the attention of the media after a several cases of a killer being caught after successfully staging murders as suicides. The National Police Agency reportedly said that 39 deaths handled by the police since 1998 as suicide later turned out to be murder and/or criminal actions resulting in death. Sometimes suicides are only found to be murders after a criminal confesses his or her past crimes to the police. Suspicious deaths in Japan only have a 10 percent autopsy rate compared to 50 percent in the United States. [Source: Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky, Atlantic Wire, September 10, 2012]

In July 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The elderly parents of a 38-year-old woman have been arrested for allegedly helping their daughter hang herself. The daughter, unemployed, told Yoshihiro Otsubo, 69, and his wife Mutsuko, 67, of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture, at about 1:30 a.m. that she wanted to kill herself, according to the Chiba prefectural police. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, July 29, 2012]

The couple allegedly made preparations for her suicide by putting up a rope in a room on the second floor of their house. They then left the house, leaving their daughter alone, police said. The two returned home at about 2 a.m. and took their daughter down from the rope, according to the police. They called the police about an hour later and reported that their daughter had hanged herself at home. An emergency squad rushed to their house and took the daughter to a hospital, but she was dead on arrival, police said. When questioned by officers of the Kashiwa Police Station, the parents reportedly said they helped their daughter kill herself because she wanted to die.

Suicide Websites in Japan

In 2003 and 2004, there were several group suicides linked with Internet sites. Between February and mid June in 2003 suicide attempts by 12 such groups of two to four people left 30 people dead and seven survivers. The victims included university students, company employees and part-time workers. In September 2004, four people who died from carbon monoxide poisoning were found in a station wagon in a suburb of Tokyo. Most were in their 20s or 30s.

In May 2005, a 34-year-old woman, a 19-year-old man and a 32-year-old man met on Kita Daito island, a remote place 400 kilometers from Okinawa, checked into a local guesthouse, rented bicycles for a ride around the island, enjoyed a dinner of sushi and a breakfast of fish and rice and were found a few hours late hanging from a beam at end of one of the island’s most famous beauty spots. The three had met on a suicide website.

In March 2006, five men and a woman were found dead in a van parked in a forest in Saitama. The vehicle had been sealed. Four coal briquettes were found inside. Three others were found dead under similar circumstances in vehicle in Aomori Prefecture. All nine victims were in their 20s and 30s.

The first known website group suicide took place in 2000 and involved a middle-aged dentist and 25-year-old girl he met on an Internet chatline. Most of the time two, three or four people are involved. In October 2004, there was a case in which seven people were found dead together,

Internet group suicides rose from 34 in 2003 to 55 in 2004 to 91 in 2005. A few died from jumping or hanging but most were asphyxiated through carbon monoxide poisoning using charcoal-burning stoves in a sealed car or room, a relatively painless way to go. The numbers are a drop in the bucket compared to the total number of suicides that take place every year.

Over a period of four months in 2005 a 37-year-old unemployed man named Hiroshi Maeue killed three people — a 25-year-old unemployed woman, a 14-year-old middle school boy and a 21-year-old male university student — he met through Internet suicide websites after promising to commit group suicide with them but instead killed them by repeatedly choking them. According to prosecutors he had hoped to obtain sexual gratification from watching their faces as they died. In 2007, he was sentenced to death.

In November 2010, four bodies were found in a van in a parking lot in Saitama. Police suspected suicide after a charcoal brazier of the type used in carbon monoxide poisonings was found.

Pattern for Website Suicides in Japan

In a typical case a person considering suicide posted a message on a suicide site bulletin board, specifying the method of suicide desired (usually asphyxiation inside a car) and asked if there were others that wanted to join him. In one case a man suggested using a portable charcoal stove inside of car sealed with tape. He was joined by three others, one of whom provided a car to drive to the suicide site.

An Internet site described in detail how to commit suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning by using portable burners with charcoal briquettes in confined spaces such as a car or room. The last message left by one man who set up a room in an apartment said: “I’m looking for people to die with. I’ve prepared everything (we need to commit suicide).” He was joined by two women.

One message found by the Times of London read: “I’m tired of living. My name is Yuki and I’m 19 this year. If there is someone who intends to commit suicide by jumping, please mail me. Don’t contact me unless you’re serious.” Another one said: “Let’s die in Okinawa. Let’s go out together near the beautiful Okinawan sea. I can pick you up if you don’t have enough money.”

In October 2007 a man with arrested in connection with his role in killing a suicidal 21-year-old woman who had contacted his suicide assistance website. The man said he sold sleeping pills to the woman for ¥200,000. The woman took 20 to 30 pills and was suffocated by the man with a plastic bag. Other people that bought sleeping from the man also committed suicide.

Reasons for Website Suicides in Japan

Explaining why Japanese prefer to commit suicide in a group the Japanese psychologist Yukoko Nishihara told the Times of London. “Japanese have weak individual identities. They feel more secure losing themselves in, and identifying themselves with a group.”

Professor Masaaki Noda, a suicide expert at Kyoto Women’s University, told the Daily Yomiuri: “I think they became so caught up in these suicide pacts that they were unable to give any thought to why they should live and were unable to think calmly about their problems. They didn’t want to die by themselves as they would have been too lonely. When only two people are involved, they are afraid of it appearing as if they were in a special relationship. That is why more people chose to commit suicide in groups of three or four.”

Authorities are trying to tackle the problem by getting servers to close down the suicide websites. Police have prevented a few would-be suicides by tapping into their computers. In at least one case a man was rescued from a gas-filled car and then charge by police with assistting in the death of the others in the car.

Bullying Suicides in Japan

See Education, Bullying

Efforts to Combat Suicide in Japan

The government only spends a few million dollars a year on suicide prevention. It has taken various actions such as issuing mental health manuals for treating depression and passing suicide prevent laws in an attempt to reduce the suicide rate to little avail.

Hot lines have had some success reducing suicide numbers but shortages of staff and funds have forced counseling centers to cut services. Hot lines received 566,00 calls, of which 2.5 percent were suicide related in 1996. In 2006, they received 704,000 calls of which 6.9 percent were suicide-related. But today, according to Adelstein, suicide hotlines in Japan are so overloaded that getting through to a live operator can take thirty or more calls. Many don’t have that patience.

One of the most effective tools against suicides has been a telephone hotline called Lifeline set up in 1971 by Yukio Saito, a Japanese convert to Methodist Christianity. It began with a single telephone in the cramped offices of a Methodist church in Tokyo and now is manned by 24 hours a day by 7,000 volunteers at 50 call-in centers. It is credited with saving thousands of lives.

In the 1990s, the prefectures on the northern tip of Honshu, Japan's main island, faced suicide rates that were double the national average, a trend experts linked to the region's stoicism, inclement weather and preponderance of elderly shut-ins. After law requiring municipalities to help stem the rising rate nationwide were passed in 2007 , mandating that each prefecture fund a prevention office, the suicide rate in northern Honshu dropped. [Source: John Glionna, Los Angeles Times, May 2011]

In 2007, central government officials passed a law requiring municipalities to help stem the rising rate nationwide, mandating that each prefecture fund a prevention office.

Jake Adelstein and Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky wrote on Atlantic Wire: Taiki Nakashita, a Buddhist priest, social activist, and counselor to those contemplating suicide, says that there is no one way to prevent suicide and no easy answers to the problem. He believes that Japanese society needs to change to support the disadvantaged and poor, adding, "Most people don't kill themselves because they want to die. They kill themselves because they don't know how to go on living. We need to make Japanese a place easier for people to live."

Understanding and Preventing Youth Suicides

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: Universities and other organizations across the nation have begun efforts to understand young persons' anguish. "I can't imagine a better life in the future. I feel it is easier to die [than to keep living]," a long-haired boy in his late teens wearing jeans was quoted as saying by Yusen Maeda, a chief priest of a temple in Minato Ward, Tokyo. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, March 10, 2012]

At his temple, Maeda, 41, counsels and discusses the problems of young people seeking his advice. In the winter of 2008, a university student came to the temple and told Maeda he was unable to join a social circle or make friends with any classmates, even after six months had passed since he entered the university. "I don't know why I'm living," he was quoted as saying. Because the student spoke in a calm manner, Maeda did not feel a sense of urgency in his message. However, he then found fresh scars from wrist-cutting on both of his arms.

The student, who met Maeda about 100 times over three years, quit university. He now is going to technical school for music in hopes of becoming a musician. "It seems he finally found a life of his own after experiencing agony. I think there should be more places where young people can bare their true feelings," Maeda said.

Tsukuba University has a psychiatrist and counselor on campus on a regular basis. According to the university's lecturer Jun Sato, 39, who meets with students for consultations, many of the students are worried about getting jobs and having relationships with friends. And an increasing number of students are in financial distress, he said.

Tsukuba, Yamaguchi and other universities have created a manual for teachers on proper relationships with students. Toyama University set up a suicide prevention office at the end of 2009. The office sometimes confirms the safety of students whose parents cannot contact them by visiting the students' dwellings. "There is little chance lately [for young people] to be present at the deathbeds of [relatives] at home. I think death has become a less serious issue because of TV games and other things. We need to teach them the importance of life and death," said Hironobu Ichikawa, advisor at Tokyo Metropolitan Children's Medical Center.

Image Sources: 1) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education; 2) Japan Zone

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013