HOME CUSTOMS IN JAPAN

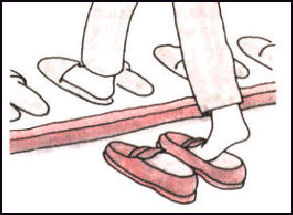

off with the shoes

on with the slippers The Japanese traditionally would speak to guests in the entrance hall or else show them to a reception hall or living-room-dining-room area. It very unusual for a visitor to come in the kitchen or the bedrooms and have a look around the house.

Respect and deference to a host is expected in both social and business situations.

Japanese tend to get less sleep than Americans. They tend to get up later and go to work later but work long hours, get home late and go to bed late.

Good Websites and Sources on General Etiquette and Manners : Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; Japanese Manners and Etiquette thejapanfaq.com/FAQ-Manners ; Ten Japanese Customs /matadorabroad.com /matadorabroad.com ; Culture- at-Work culture-at-work.com ; Executive Planet executiveplanet.com ; Kwintessential kwintessential.co.uk ; Eating and Drinking Customs: Essential Japanese Guide essential-japan-guide.com ; Sushi Etiquette homepage3.nifty.com ; Right Way to Eat Sushi snippets.com ;Drinking Customs japanvisitor.com

Books: “The Traveler's Guide to Asian Customs & Manners” by Elizabeth Devine and Nancy L. Braganti. “Kata: The Guide to Understanding and Dealing with the Japanese!” By Boye Lafayette De Menter (Tuttle, 2003). Sources for advise on Japanese and international etiquette include Mary Kay Metcalf of Creative Marketing Alliance in New Jersey and Chicago-based Japan Intercultural Consulting. Links in this Website: JAPANESE CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE HOME, EATING AND DRINKING CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Shoes, Slippers and Dogs in Japan

According to Japanese custom, people are supposed to take off their shoes when entering a house. The shoes are taken off at the “genkan” (threshold, or entrance area) inside the house and one has be careful not to step on the genkan with their barefeet or socks (Japanese step out of the heels of both shoes first and then step into house without stepping on the threshold). The custom was developed to keep the floors in the house and especially hard-to-wash tatami mats clean.

Often Japanese step into slippers for walking around in the house but remove their slippers when entering a tatami-mat room. If you go the bathroom you put on a pair of plastic slippers in the bathroom and then change back into the original slippers when you step out of the bathroom.

It takes some skill to take off and especially put on your shoes at the door with grace and ease. It is a bad idea to wear hiking boots are shoes that require lacing up or are difficult to step in and out of. The custom of removing shoes was developed when people mostly wore sandals. Shoe horns are often available. If you need to sit to put on or remove your shoes apologize.

In Japan, there are too kinds of dogs: small dogs that are allowed in the house and outdoor dogs that have to stay outside and are not allowed inside because of worries that they will dirty the floor or the tatami mats with their feet.

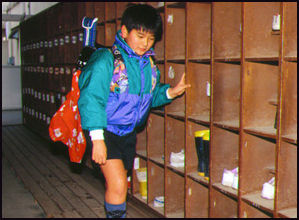

Shoes and Umbrellas in Schools, Hotels and Doctors Office

school shoe boxes Japanese children put their shoes into special boxes and change into slippers when they arrive at school. They wear a third set of footwear in the bathrooms, a forth set in gym class, and change back into the street shoes when they go home.

Generally it is okay to wear shoes in the rooms of a hotel (but not a traditional Japanese inn). Shoes are alright in restaurants with tables. In restaurants where people sit on the floor shoes must be removed. People take off their shoes off in dentist offices and small clinics but keep their shoes on in a big hospital.

Some Japanese drag their feet when they walk. This is because the y are used to wearing slippers and this the easiest way to walk when you wear slippers.

When entering a store, restaurant or public with an umbrella, you should put the umbrella in the umbrella holders near the entrance. Sometimes you need to put the umbrella in a plastic bag before putting it in the umbrella holder.

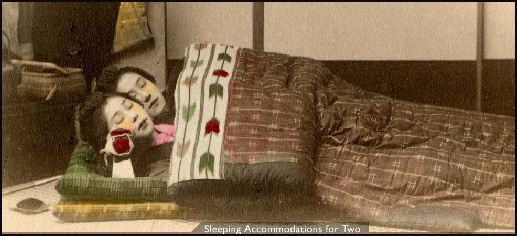

Sleeping and Sitting on the Floor in Japan

A lot of Japanese sleep on the subways and trains. At home they often sleep on futons (but many also sleep on beds). In the summer they sleep under towels. After waking up a futon sleeper is expected to fold up his or her futon and blankets and place them in a closet or against a wall.

The Japanese spend a lot of time sitting on the floor, and if given the choice some would rather sit or lie down on a hard floor than relax on a bed or in a comfortable chair. When sitting on the floor many people sit on cushions.

sleeping on the floor in the 19th century

Koreans also spend a lot of time on the floor and take their shoes off in the house while the Chinese sit on chairs and leave their shoes on. Chairs were introduced to China about a thousand years ago by the Mongols, who never conquered Japan or Korea. This is believed to be the reason why they use chairs and Koreans and Japanese don't.

The preference for sitting on the floor goes hand in hand with not wearing shoes in the house. Japanese and Koreans don't want to sit on a floor dirtied by people's shoes. If you sit in a chair it doesn't make as much difference if the floor has a little dirt.

The “seiza” style of sitting on your knees — with the legs bent and tucked under the bottom — is regarded as polite. The more relaxed “agura” style is referred to as “Indian style” in the United States. Woman sitting the seiza position that perform a proper bow do so with their hands on top of each other and the elbows out.

Women are not supposed to sit cross-legged on the floor. They are supposed to sit with their legs bent under them or bent to the side (both positions are generally very uncomfortable for Western women for long periods of time).

JAPANESE EATING CUSTOMS

Erect chopsticks are a no no

because this is how rice is

given to the dead Meals prepared in traditional Japanese style are served on low tables set up on the floor. People sit on the floor and don't start eating until the oldest male or someone says lets eat and everybody says “itaeakimas”. When offering a plate, dish, glass or bottle to someone who is older than you, you show respect by using two hands to present the object.

Japanese generally don't use napkins. At restaurants, customers are served hot towels, which sometimes can be used like a napkin. At home people sometimes use tissues. In any case, it is good idea to have your own tissues handy in case you need one. Many Japanese carefully fold their towel or tissue after finishing their meal rather than wadding it up.

Sometimes Japanese don't drink anything with a meal. Sometimes water or green tea is served. Often a soup serves the same purpose as a drink. It is served in a lacquered bowl which is picked up and sipped like a drink. Items in the soup are picked out with chopsticks. A spoon is not used. The Japanese also tend to eat their rice separately from the main dish. They often take one bite of rice and then one bite of the main dish so it mixes in their mouth.

Eating Don'ts in Japan

Japanese consider it uncouth to lick your fingers or blow your nose, especially when eating. Japanese are offended if you dump soy sauce or salt all your food. They regards this as an efforts to mask the flavor of food that taste bad. If you use a toothpick cover your mouth while you do it. Also remember that an empty rice bowl if often a sign that you have finished eating.

Japanese consider it somewhat rude to eat in front of non-eating people, or to eat while walking down the streets. The latter custom dates back to a time when eating in public was considered mean to people who didn't have enough to eat. In 8th century Japan there was a law that required anyone caught in the act of drinking while standing up to commit suicide. With the rising popularity of fast food, many people now eat on the streets on subways. Eating on trains is the norm.

Slurping in Japan

Japanese often make loud slurping noises when eating noodles. Making noise is not considered impolite, rather, it is considered a compliment and an expression of enjoying the food. One man told AP, "It'll be a truly lonely feeling when nobody makes slurping noises anymore." In some situations, a particularly loud slurp means you've finished eating.

Many Japanese, especially older men, believe that noodles taste better when they hot and drenched in broth and are best appreciated when slurped. Among the ranks of unapologetic noodle slurpers are Prime Minister Junichito Koizumi.

Sometimes a well-timed burp is also taken as a compliment.

These days many Japanese, especially young women find noodle slurping noises to be offensive and worry about splattering broth on their designer clothes. "Slurping is for old men," one office worker told AP. "Slurping has nothing to do whether it taste good or not."

Chopsticks, Servings and Dishes in Japan

Japanese eat all Japanese-style meals with chopsticks. Even soup is consumed with chopsticks (the ingredients are eaten with chopsticks and the soup is drunk from the bowl). Many Japanese pick up their rice bowl when they are eating and place it under their mouths and use it as a safety net for anything that falls down. When a rice bowl isn't available they place their free hand under their chopsticks for the same purpose. Leaving chopsticks sticking up in a bowl of rice should be avoided. It is a sign of death. Most food is soft or small enough that it can picked up or cut with chopsticks. Forks, knives and spoons are used for eating Western food.

Japanese prefer disposal wooden chopsticks at restaurants and laminated wooden ones at home. Vietnamese often use plastic chopsticks while Korean tend to use metal ones for food dishes and a sppon for rice. In Japan, when you finish you using your chopsticks you should set your chopsticks in a little chopstick tray or place them horizontally on your plate or bowl in such a way that they are not pointing at anyone. If you forget some of these rules or get mixed up it is usually no great tragedy.

Meals often consist of many dishes, which are passed around and carried from the kitchen on trays and placed in the table. Each person serves himself some food from the dishes onto small plate. Sometimes there are different plates for different foods.

Ideally you should serve yourself with one set off chopsticks and eat with another. People often serve themselves by taking food from a serving dish with a serving spoon, their fingers or communal chopsticks and then placing them on a small plate in front of them. If there is no serving spoon or communal chopsticks, you should turn your chopsticks around and pick up the food with the end of your chopsticks that have not been placed in your mouth.

Restaurant Customs in Japan

When eating in a fancy restaurant with tatami mat floors you should remove your shoes when you enter the restaurant and change into slippers, which should be taken off before entering the eating room. If you go the bathroom you put the slippers on again and then change into a pair of different slippers in the bathroom and then change back into the original slipper when you return to the eating room.

Customers entering a restaurant are greeted with the expression “Irasshaimase” ("Welcome") and asked by a waitress "”Namei sama”" ("How many in your party"). You can answer with your fingers. That is what most Japanese do. After being seated usually you will be given a hot towel to wipe your hands and face,

Japanese sometimes appear rude to service personal at restaurants, hotels and stores’shouting and ordering people around. This kind of behavior is considered acceptable.

Paying the Bill in Japan

Japanese sometimes split the bill; sometimes they don't. When splitting the bill, usually the older person pays a little more than the others. When not splitting it, a designated host pays with the understanding that the other people will pay him or her back sometime in the future. As a rule, the person that invites the others pay for the meal.

When foreigners are involved, Japanese usually insist on paying the bill even in situation when the foreigner should pay. Sometimes physical struggles break out for possession of the bill. Japanese are insistent about paying the bill because they feel it their responsibility uphold the reputation that Japanese are hospitable people.

It is considered tacky for the host to pay in front of his guests, so usually what the host does is excuse himself under the pretext of going to the bathroom and pays the bill privately.

Tipping is not practiced in Japan. Japanese often pay with large bills rather than credit cards or small bills. To make a good impression at a good restaurant, something Japanese like to do, the host often pays with crisp new bills with consecutive numbers. Banks are used to exchanging old bills for news ones for this purpose.

Japanese Drinking Customs

pouring sake Japanese usually don't start drinking until someone offers the toast "”kampai”" — (dry glass). The Chinese and Koreans use the same word for their toasts. As the evening progresses, Japanese often shout "banzai!" three times. It means "live ten thousand years" and is the equivalent of saying "hip. hip, hooray!" The custom of raising a glass and saying a loud toast caught on in the later half of the Meiji Period (1868-1912) and was influenced by the British Royal navy.

When drinking, one should not drink from the bottle or fill his or her own glass. The polite thing to do is fill someone else's glass and they in turn will fill yours. In some situations, it is rude to turn down a drink that is being offered to you. To avoid drinking to much keep you glass full. To avoid being rude accept a drink the first time it is offered to you by a particular individual. The second time he offers it is acceptable to politely say no.

These days Japanese often order beer by the glass rather than the bottle which means they are less likely to pour drinks for each than they did in the past. Often younger people hold the bottle with one hand when pouring for older people when etiquette requires them to hold it with two hands. This trend is attributed to decline if drinking between older and young people.

Sake Drinking

Sake is traditionally consumed in a porcelain cup called a “sakazuki”, or Japanese cedar boxes called “masu”. These containers are small and hold only a couple of swallows. This means that sake drinkers are usually busy filling one another's cups. Sometimes salt is placed on the rims of masus. Many true saki drinkers don’t recommend using masu because they are awkward and add a wood taste to the sake. Wineglasses are better.

Lisa Takeuchi Cullen wrote in Time: “Enjoying sake properly employs all the senses. First listen for a clear, springlike glug as it is poured. Next look for clarity, sheen and color in the cup. Then sniff the brew for bouquet and personality. Taste for all those things, and feel it swell going down.”

Fifteen degrees C is the recommended drinking temperature for most types of sake. Once a bottle has been opened it is good to drink it right away as oxygen will adversely affect the taste. Refrigeration is important. Avoid sake that is displayed on a liquor store shelf or has been transported without refrigeration. Thermoses are used to keep sake at the appropriate temperature at all times.

Tea ceremony-style

tea drinking

Japanese-Style Tea Drinking

The first step in drinking tea Japanese-style (not the tea ceremony) is to place all the necessary pots, cups and utensils in neat order on a small table. Fresh spring water is boiled on a special brazier and then poured into the handle-less cups and the pot to warm them — and then the water is thrown out. Water is next poured into a tea bowl so that it will be at the right temperature when the tea is ready.

The lid of the tea container is removed and placed on a special stand and the tea — about two grams per person — is placed in the pot with a special ladle and the slightly cooled water (about 70 degrees C to 80 degrees C) in the tea bowl is slowly and evenly poured into the tea pot and the lid is put back on the teapot. The tea brews for about two minutes before it is served.

The tea is then poured into ceramic cups with no handles a little bit at a time to make sure everyone receives tea of the same strength and quality. Tea drinkers are often served three cups: the first of which is fragrant, the second, strong, and the third, delicate. When a man prepares match for a woman it often has romantic implications,

Describing how tea is served at a tea tasting session at fancy tea house Elizabethan Andoh wrote in the New York Times, "A tiny clay pit holding the leaves and two small porcelain cups are brought to the table with a thermos of hot water. The teapot is set on a clay trivet, and scalding water is poured over and into the pot. (The trivet doubles as a sink, catching overflow.)"

"After a few moments the first infusion is poured into the slender and taller cup, then transferred immediately to what looks like a sake cup or shot glass. The first cup becomes a snifter — indeed the aromas are intense — and the second cup is for sipping. As the hot tea warns the cup, the design painted on the snifter changes color, from green to red."

Utensils and Drinks Match the Food and Occasion Rather than the Person

Kate Elwood wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “When I first came to Japan, many years ago, I went to a restaurant at a tourist spot with a Japanese friend named Momoko. It was one of those basic eateries common at such areas, which offer a variety of dishes, none very expensive, none terrifically wonderful. We both chose pasta. I opted for a Japanese-style spaghetti with sansai wild vegetables in it, and Momoko ordered the standard Bolognese sauce. [Source: Kate Elwood, Daily Yomiuri, November 30, 2010]

“The waitress then brought our dining utensils and I thought she had made a mistake. I was given chopsticks while the waitress placed a fork by Momoko's place. I had no problem using chopsticks, but if anyone was going to get a fork I would have assumed it would be the newly arrived awkward American, not her poised and stylish Japanese friend. Momoko, however, found it more likely that cultural cutlery notions were at work. Quasi-Japanese-style food, ergo Japanese-style implement. Looking around the restaurant at other tables, Momoko seemed to be right.”

There is certainly some mixing of cultures, as the sansai spaghetti demonstrates, but at the same time, there is often a tidy allocation between the two traditions. Japanese tea goes in Japanese teacups, coffee in Western-style cups and saucers or mugs. Miso soup belongs in a lacquer (or lacquer-like) bowl, Western soup in china. Despite the static premise, various cultural go-betweens are quite active. In family restaurants, rice is like an agile and versatile actor, running offstage in one costume, only to emerge minutes later in new attire accompanied by other props and with a different name and role. Rice that is part of an order of Japanese food is called gohan, and is served in a Japanese rice bowl, with chopsticks. Rice brought in tandem with Western dishes goes by the phonetic translation raisu, and appears on a plate, to be eaten with a fork.”

I was reminded of this dichotomy recently when I read an article by cultural anthropologist Ofra Goldstein-Gidoni titled The Making and Marking of the "Japanese" and the "Western" in Japanese Contemporary Culture. Goldstein-Gidoni similarly observes the gohan/raisu split, along with a range of other interesting divisions along wa-yo lines. Perhaps somewhat playfully, the ethnographer refers to "dangerous liaisons," such as green tea and sandwiches. Goldstein-Gidoni emphasizes that such rules of cultural interface are more strictly adhered to in the public sphere than in private homes. Nonetheless, the choice of green tea as a symbol of division seems a bit weak. In fact, green tea is Japan's Coke. Decades of slogans for Coca-Cola all seem to fit green tea's role in Japan: "Coca-Cola revives and sustains" (1905); "Thirst asks nothing more" (1939); "Where there's Coke, there's hospitality" (1948); "Things go better with Coke" (1963).”

“But while green tea is the "passport to refreshment," to borrow another Coke slogan, Western beverages may have their visas revoked at the point of entry into Japanese culinary territory. Another of Goldstein-Gidoni's examples is coffee and sushi. Oh my! Whether it can be called a "dangerous liaison" or not, that combination certainly goes in the "when pigs fly" category. Even somewhat more palatable mergers such black tea and Japanese wagashi sweets are almost certain to get the designation of awanai (doesn't match). The pairing is not dangerous perhaps, but evo

Image Sources: 1) Illustrations, JNTO, 2) phots, Andrew Gray Photosensibility (slurping) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education (sleeping), Hector Garcia (chopsticks)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013