DUTIES AND LIFESTYLE OF THE JAPANESE EMPEROR

Three imperial symbols Members of the Japanese royal family aren’t allowed to have last names, personal wealth, publically-expressed opinions, and, in the view of many, lives. The main job of imperial family members is to attend official functions, which they do nearly every day, and to partake in religious rituals inside the palace.

The Regalia of the Emperor (The Three Treasures) includes the sacred mirror (kept at Ise Shrine), the curved jewel and the sacred grass cutting sword (kept at Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya). According to legend they were given to the Imperial family by the sun goddess Amaterasu. They are symbols of the Emperor's power and authority.

It’s hard to know much detail of goings-on inside the Imperial Palace. Palace officials restrict their weekly briefings to a select group of journalists from the mainstream Japanese media who in turn tend to acquiesce to imperial requests on what not to write.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: JAPANESE EMPEROR AND IMPERIAL FAMILY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE EMPEROR’s DUTIES AND LIFESTYLE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EMPEROR HIROHITO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EMPEROR AKIHITO AND EMPRESS MICHIKO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CURRENT JAPANESE ROYAL FAMILY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; PRINCESS MASAKO Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Heraldica.org article on the Japanese Emperor heraldica.org ; History on Unofficial Japan Royals Pagesetoile.co.uk ; Stanford SPICE links to articles (compiled in 2004) spice.stanford.edu ; Japanese Creation Myth Washington State University ; ; Wikipedia article on the Emperor of Japan Wikipedia ; Opening Imperial Tombs msnbc.msn.com ; Book: Secret History of the Yamato Dynasty prnewswire.co.uk ; Modern Imperial family The Royal Forums on the Imperial Family of Japan theroyalforums.com ; Royalty/nu Links royalty.nu/Asia/Japan ; Imperial Family of Japan Blog imperialfamily.blog54 ;Unofficial Japan Royals Pages etoile.co.uk

Imperial Palace in Tokyo Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Imperial Household Agencysankan.kunaicho.go.jp ; Map /gmap.jp Good Article by Robert Poole, National Geographic, January 2001. Imperial Palace in Kyoto Imperial Household Agency sankan.kunaicho.go.jp ; Kyoto Travel Guide kyoto.travel Shugakuin Imperial Villa: Imperial Household Agency /sankan.kunaicho.go.jp ; Photes japannet.de ; Wikipedia Wikipedia Katsura Imperial Villa: Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Imperial Household Agency sankan.kunaicho.go.jp ; Tour of Katsura Rikyu katsura-rikyu.50webs.com Katsura Rikyu ranked No. 2 as the best garden in Japan by the U.S. publication the “Journal of Japanese Gardening” . The gardens at Adachi Museum in Yasugi Shimane have been ranked No. 1 for four consecutive years. Ise Shrine Isejinguisejingu.or.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Wikitravel Wikitravel Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO and Ise area JNTO ; Ise Jingu isejingu.or.jp Udo Jingu Shrine (near Nichinan 20 miles south of Aoshima In Miyazaki Prefecture) is located in a large sea-eroded cave on the Pacific Ocean at the tip of Cape Udo. It is dedicated to the mythological father of the mythological first emperor of Japan.

Japanese Royal Marriages

Royal family members become formally engaged after a Nosai-no-gi ceremony in which the couple delivers a message with a list of betrothal gifts to the Grand Steward of the Imperial Household Agency. The couple then meets with the Emperor and tells him the messenger had made a visit and present the gifts. The ritual takes about 15 minutes. The gifts include male and female sea bream, horsetail shoots, a bottle of sake and bolts of silk from which the wedding dress is made.

Later the Kotsuki-no-gi ceremony is held to determine the wedding date. Three days before the wedding the couple bids farewell to their ancestors in the Sanpai-no-gi ceremony and thank their parents in the Choken-no-gir ceremony.

Imperial family wedding feature a Shinto ceremony presided over by Ise Shrine’s Daiguji chief priest in which the couple exchange nuptial cups and branches of trees regarded as sacred in the Shinto faith. The bridegroom reads the marriage vows and the couple bows before an altar of the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami and offer their thanks to the Emperor and Empress.

For imperial princesses, a few days before the wedding the princess is dressed in an elaborate kimono and participates in a formal farewell address to the Emperor and Empress in a hall in the Imperial Palace. She also bids farewell to ancestors worshiped as the deities from which the Imperial family is said to have descended.

Princesses who marry commoners become commoners. They are given a tax-free lump sum of around $1.5 million (the equivalent of 10 years of annual salary) after they marry. Their names are removed from the royal register and a new family register is started for them. They also lose their access to Imperial servants, chauffeurs and attendants and have to sign up for pensions and health insurance and take public transportation, taxis or drive like ordinary Japanese. Princes retain their royal titles no matter who they marry.

Royal Child Rearing and Communication in Japan

Until fairly recently, royal children were removed from their parents at the age of three and raised in an Imperial nursery and looked after by their own doctors, nursemaids and teachers. The everyday care of the royal children was the duty of wet nurses and nannies. A princess once confessed, "I did not shed a tear when my mother died, but I was sad and kept crying when my nanny resigned.” These days royal parents take on more child rearing responsibilities than their ancestors.

The Chakko no Gi ceremony marks an Imperial child reaching the age of five. Similar to Shichiosan festival for ordinary children, the Imperial child dons a special hakama skirt and prays at an Imperial palace sanctuary and greets the Emperor and Empress.

When the crown prince become an adult he often rarely communicates with the Emperor. Even today, according to tradition, the crown prince does not telephone the Emperor to make an appointment for a visit and the Emperor does not offer advice to the crown prince. Imperial Household Agency stewards make arrangements for both sides and the grand steward is responsible for solving problems.

Royal Education in Japan

Princess Aiko at kindergarten The children are expected to attend the Gakushuin schools — formerly the Peers School from the old aristocracy — from kindergarten to high school. Many continue on at Gakushuin University. Males are expected to be well versed in the classics, Imperial history, poems, ethics, mathematics, classical Chinese and horseback riding. Girls learn flower arranging and traditional dancing. Later many study abroad.

On the issue of the education for a child likely to become Emperor, Isao Tokoroma, an expert on Imperial affairs at Kyoto Sangyo University, told Kyodo news. “The young prince should be given an Imperial education through which he can learn about his responsibilities. He needs to acquire the kind of mind-set that is indispensable for an emperor, such as stoic courtesy, discipline and consideration for others through experience.”

Emperor Hirohito attended a school for seven years with five “classmates” selected especially for him. The current Emperor was educated under the guidance of a former university president and given special classes on Western thinking and manners by a private tutor named Elizabeth Vining. The current crown prince and his brother attended Gakushun from kindergarten through university and were allowed to have relatively normal social relationships there.

Gakushuin opened in 1847 near the end of the Edo Period near the Imperial Palace in Kyoto for children of court nobles and moved to Tokyo in 1868 as part of the Meiji restoration. Regulationd for Imperial family members “ enacted in 1926 “ stated that all Imperial children must attend Gakushuin University or Gakushuin Women’s College. The regulations were abolished after World War II but the tradition of sending royal children there continued. In 1963 a kindergarten was opened so the crown prince could attend.

These days more and more royals are bypassing Gakushuin family schools “ whose curriculum is regarded as too old fashion and course offerings does not offer classes in fields the young royals are interested in “ and choosing other schools. The crop of young royals that entered university in 2008 and 2009 chose Waseda University, Josai International University and Christian International University over Gakushuin University.

Prince Hisashito, perhaps the future Emperor, is attending Ochanomizu kindergarten in part because his parents, Prince Akishino (the crown princes brother) and Princess Kiko, wanted him to attend a school with a three-year kindergarten program rather than one with two year program like what Gakushuin’s. Imperial Family watchers say it is likely that the young prince will attend Ochanomizu primary school and become the first royal not to attend Gakushuin primary school.

Imperial Pregnancy and Birth Rituals in Japan

A traditional ceremony for a safe delivery is held during the fifth month of pregnancy. With the help of her ladies in waiting, the crown princess or Empress wraps a broad sash around her abdomen as a temporary maternity belt to symbolize her wish for an easy delivery. The imperial couple then reports to the Emperor at the Imperial Palace that all has gone smoothly. The ceremony is held on the Day of the Dog on the old lunar calender. Dogs are symbols for a safe birth.

In the ninth month of pregnancy a male member of the Imperial family delivers a sash to the princess through an envoy. The sash is taken to three shrines at the Imperial Palace and then put on by the crown princess, with the help of her ladies in waiting, while the crown prince looks on.

On the day of the birth, the Emperor presents his grandchild with a sword, symbolizing self-defense. On the seventh day after the birth there is a special ceremony in which the name of the new member of the Imperial family is announced. See Princess Aiko, Royal Family.

The Emperor's plane

Duties of the Japanese Emperor and Empress

According to the Japanese constitution, the Emperor is limited to symbolic acts that unify Japan and keep alive Japanese traditions. He is forbidden from engaging in or interfering in political matters.

The Emperor appoints the Prime Minister and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, attests cabinet appointments, convokes the National Diet, promulgates laws and treaties, awards honors and receives foreign ambassadors. At the Imperial Palace the Imperial family hosts hundreds of ceremonies, audiences, teas, lunches and dinners throughout the year. They also attend annual award ceremonies of the Japan Academy and the Japan Academy of Arts and take in an occasional sumo match.

Ise Shrine, where Empeor

performs some rituals The Emperor’s main duties include visiting with dignitaries and world leaders, hosting state dinners, making appearances at important festivals, performing opening ceremonies at new libraries and parks and comforting disadvantaged people or victims of disasters.

The Japanese rarely see members of the royal family except on their birthdays, a few isolated ceremonial functions and before their trips abroad. Occasionally they show up in the exclusive seats reserved for them at baseball stadiums and major concert halls (when the royal family isn’t there they are covered). The Emperor is driven around in a modest-looking black Toyota, with a red flag by the hood and gold chrysanthemum seals on the doors. The Emperor's limousine stops at red lights and pulls over for ambulances just as the vehicles of common Japanese citizen have to do.

According to custom the Empress is always supposed to walk two respectful steps behind her husband and follows him when he enters a room and speak only half as much as he does. The Empress is not supposed to drink too much water on long flights so she does have to make needless trips to the bathroom.

Empress Michiko once said, "For all people who live in this society, there are roles to be played. The roll expected to be played by us, members of the imperial family, is one of devoted moral support in contrast to the practical demands requested of an administrative system."

Imperial Holidays and Rituals in Japan

The Emperor ascend to the throne in a grand ceremony in Kyoto. During the central ritual he walks up to a small Shinto shrine and informs ancestors and spirits that he now occupies the throne. Later, dressed in an orange robe, he is introduced as emperor to the world by the Japanese prime minister.

The Emperor’s birthday is national holiday. On that day the Emperor usually appears in the balcony of the Imperial Palace with other members of the royal family and gives a short speech.

The Emperor, embodying the god of the ripened rice plant, plants the first rice of the spring and harvests rice from the plants of the autumn. In one of the most solemn Shinto ceremonies of the year the Emperor, acting as the country's chief Shinto priest, ritually sows rice in the royal rice paddy on the grounds of the Imperial Palace.

Great Food Offering by the Japanese Emperor

The Great Food Offering — in which the Emperor spends the night with the Sun Goddess as a dinner guest — is something every emperor is required to do shortly after ascending to the throne. First recorded in A.D. 712, the ritual takes place at night because the Sun Goddess is in the sky during the day.

The rite follows a ritual bath, symbolizing purification, and takes place in two simple huts, made of unpealed logs and lit with oil lamps, erected on the Imperial Palace ground in Tokyo. The huts are believed to represent the original first huts where Jimmu Tenno communed with the Sun Goddess.

During the Great Food Offering, the Emperor absorbs some of the Sun Goddess spirit and thus "becomes a kind of living ancestor of the entire Japanese family." The pre-World War II belief that the Emperor was a living god is based on this ritual. Murray Sayle wrote in the New Yorker, "I witnessed the most recent Great Food Offering....from my position behind a police barrier a hundred yards away. During my chilly vigil, all I saw was a figure in white silk — presumably the Emperor — flitting from one small building to another. It took perhaps one second in all."

No one but the Emperor has ever witnessed the ceremony. According to a press release from the Imperial Household Agency, "The new Emperor...offers newly-harvested rice to the Imperial Ancestor [the Sun Goddess] and the deities of Heaven and Earth and then partakes of the rice himself, expresses gratitude to the Imperial Ancestor and these deities for peace and abundant harvests, and prays for the same on behalf of the country and people."

Many wonder why this ritual is shrouded in secrecy. Some believe that is because there is sexual aspect to the ritual. The Emperor is reportedly naked for part of the ritual and the only furniture in the huts are "throne couches," which look a lot like beds.

Holiday Duties of the Japanese Emperor and Empress

The Emperor delivers a New Year’s message from a balcony of the Imperial Palace. In 2008, flanked by members of the royal family and viewed by a crowd in the thousands, he said, “I am pleased to celebrate the New Year with you...I wish for the happiness of people in our country and peace in the world” and expressed sympathy for those affected earthquakes and other hardships.

Every year the royal family usually shows up the New Year's Poetry Party, where 100 poets and dignitaries chant 31-syllable waka poems — arranged in five lines with a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable structure” in melodious style in an event that dates back to the 10th century. The Emperor and Empress often recite four poems a piece, with the Imperial children taking part as well.

Greeting the public on New Year's Day

A poem by the Emperor recalling a visit the Swedish city Upsala to commemorate the scientist Linnaeus went: “Remembering Linnaeus/And the binomial nomenclature/ He established,/ this city I have come/ With the King of Sweden.”

On the poetry reading Richard Lloyd Perry wrote in the Times of London, the poets “lay their positions on the line, resolutely in favor of good things (full moons. Motherhood, binomial nomenclature), and forcefully against bad things (earthquakes, wars). From time to time though, glimpse of something edgier flash between the lines, and experienced imperial-watchers keep a vigilant watch for such moments...There was the Crown Prince Naruhito’s 1993 poem about a flock of cranes and the fulfillment of childhood dreams — a hint he was about to announce his engagement. Then there was the Empress’s waka about a visit to a Dutch war memorial un which she made references to wreaths laid by anti-Japanese protesters.”

The annual Spring garden party hosted by the Emperor honors scientists, statesmen, athletes and people who have distinguished themselves in some way. Other events honor civil servants and other people deemed worthy of being honored.

Special awards given by the Emperor include the Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum

Japanese Emperor and the Press

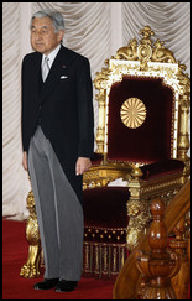

Emperor at Parliament Akhito was the first Emperor to introduce unscripted press conferences, most of which are held on the birthday of royal family members. The Japanese royal family is covered in the Japanese media by the "press club," an elite group of reporters that can be counted on to ask polite, non-threatening questions. Critical coverage is taboo. Reporters never ask the questions people want to know. Instead the Emperor gives a little speech about the events he’s planning to participate in.

Royal press conferences follows strict protocol. Invitations comes with seven pages of instructions about protocol. Washington Post reporter T.R. Reid said, "We were told precisely where to stand, precisely where to clip on our name tags and precisely how to greet the royal couple (with Western-style handshakes rather than Japanese-style bows). When the press conference is over, everyone bows and the Emperor quietly walks out.”

Journalists are not allowed to quote the Emperor and they can not carry cameras, tape recorders or even notebooks when meeting with the royal family. Photographers are encouraged to avoid unflattering pictures. Question are submitted weeks in advance and the answers are believed to be put together with the help of Imperial Household Agency. One reporter told the New York Times, “It is easier to interview the head of the KGB in Moscow or the NSA in Washington than to get time with these people.”

"There is a special vocabulary among headline writers for imperial matters," Reid wrote. Akhito never "gives a speech,” rather he "expresses the honorable words." There are special words for a royal wedding, a pregnancy, a birth and a birthday. And when an emperor dies, there is a special headline word used for that purpose: hogyo, a term that literally means 'the collapse of a mountain.'" [Source: T.R. Reid, Washington Post, June 11, 1994]

ourist view of the Japanese Imperial Palace

Japanese Imperial Palace

The Imperial Palace, near Tokyo Station, is where the Emperor and the royal family reside. Surrounded by a moat patrolled by swans and traversed by a beautiful "double bridge," the palace is made up of many buildings that have been reconstructed several times. Most of the palace is closed to the public on all but two days of the year (January 2nd and the Emperor's birthday on December 23rd). But visitors can still walk around the moats and some of the gardens and catch glimpses of some of the structures inside.

The 284-acre Imperial Palace grounds is covered mostly by lush forests and gardens. It occupies some of the world's most valuable real estate. In the "bubble economy" in the 1980s, the land occupied by the Imperial Palace grounds was worth more than the entire state of California.

The Imperial Palace was formerly known as Edo Castle. Built between 1603 and 1651, the original Edo castle was the home of the Tokugawa shogun and at one time was the largest castle in the world. Built "unparalleled under heaven," it and the Tokugawa dynasty were so formidable that the castle was never attacked. The massive boulders in the rough-hewn walls were brought in at considerable expense and effort from the provinces in the 1600s by the shogun’s overlords. This castle was destroyed in the Great Meireki Fire in January 1657.

In 1869, when the capital of Japan was moved from Kyoto to Tokyo, Edo castle became the home of the Emperor and was later renamed the Imperial Palace. The only surviving original structures are moats, walls made with huge stones and a few gates and guard towers which are set at intervals around the walls. In 1888 the palace was rebuilt. Most of these structures were destroyed by the Great Tokyo Earthquake of 1923 and by firebombing in World War II. The broad green-roofed palace, where the royal family lives, is known as the imperial residence.

The current palace was built to replace the Meiji Palace, which burned down during a World War II air raid. It has a floor space of 23,000 square meters, was designed to avoid letting in much outside air as it was built during the years of high pollution. The current Imperial residence, on the other hand, was completed in May 1993. It has an area of 4,940 square meters, and consists of areas for meeting guests, administrative work and private rooms.

Among the buildings in the palace are the Archery Hall, the Kendo and Judo Hall, the Music Department, the Imperial Stables and the Imperial Guard House. The gardens are quiet and peaceful. The East Garden in particular is designed as place for quiet mediation and rejuvenation. It features well-tended paths lines with azaleas, zigzag bridges that confuse evil spirits and ponds full of koi fish. The dense beds of irises are laid out so the Courageous Lion and Monkey Dance don’t disrupt the Boats of Edo and the Wet Crow. Fukiahe Garden is the wild and unkept. here you can find egrets searching for fish the marshes and hawks hunting small birds. The Emperor likes to beginning his day by taking a walk here.

Other Imperial properties include the Imperial Stock Farm is a 620-acre expanse, that produces milk, vegetables and horses for the Imperial Palace according to strict standards. The farm is kept under extremely tight security. The royal family also has a palace in Kyoto which they visit once every year or so. There is talk of returning the royal family to Kyoto and having them perform Shinto duties that were stripped from them 500 year ago.

In August 2009, the palace of the crown prince and his family were remodeled to be more energy efficient.

Gilded Cage of the Japanese Imperial Family

The Royal family lives in "gilded cage." There is little socializing except within the royal family. Simply inviting someone over to the palace is often a time consuming event that has to be planned weeks in advance and needs approval of the Imperial Household Agency (IHA). Many members don’t even have their own direct phone lines.

There are virtually no opportunities for paparazzi style photos. The Japanese royal family rarely leaves the palace or their royal residences. Unlike royal families in Europe, there are no roped off tables at fancy restaurants, yachting weekends or nights out at nightclubs. The members of the Japanese royal family have no money of their own. All their expenses are paid for by the state and everythinghas to be accounted for.

The present isolated state of the Royal Family dates back to Yoshihito, the Taisho Emperor, and the son of the Meiji Emperor Mutsuhito. He tried to become a truly popular leader. The oligarches reacted by isolating the Imperial Family into "birds in a cage."

Japan’s Imperial Household Agency

Everything the royal family does in public is stage-managed by the Imperial Household Agency, a 1,124-member bureaucratic organization that technically gets its orders and funding (about $100 million a year) from the elected government but seems to act according to its own rules.

The Imperial Household Agency does things strictly by the book following traditions and rituals. Makoto Watanabe, the Grand Chamberlain, told National Geographic, "Some of the media think that this a very traditional, strange tribe who hide behind the chrysanthemum curtain just praying to god. And some think it’s a very modern existence. Actually it's a combination of the two."

The Imperial Household Agency can be traced back to the 7th century when a references was made of it in Imperial documents. The modern Imperial Household Agency was formed in 1869 after the collapse of the shogunate during the Meiji period. It became powerful when the eccentric Emperor Taisho was on the throne and regulations were established and direct quotes were banned as a way of protecting him from embarrassing himself and the country.

The Imperial Household Agency was very powerful before World War II when its authority was unquestioned. Known as the "the ministry above the clouds,” it was not overseen by any government body. The organization was almost eliminated along the Emperor after World War II. Since the war its seems to have devoted its energy to controlling the smallest details.

Responsibilities of the Imperial Household Agency

The main responsibility of the Imperial Household Agency is to make sure only positive information is released about the royal family. The agency is very strict and controlling. The Emperor's schedule, his orders and even speeches are all authorized and approved by the Imperial Household Agency.

Some credit the Imperial Household Agency with helping the Japanese Imperial family avoid the kind of scandals and overexposure that have hurt the British royal family. Other say the stuffy agency makes the Imperial family come across as cold and distant.

The Imperial Household Agency distributes most pictures of the royal family to the press, accepts and rejects written question from the press to members of the royal family for rare press conferences and often ghost writes the answers.

Employees at Japan’s Imperial Palace

Many of the employees of the Imperial Household Agency come from old aristocrat families. Makoto Watanabe, the Grand Chamberlain to His Majesty the Emperor, probably spends more time with Emperor than any other person with the exception of the Empress. Watanabe acts as a private secretary and confidant.

Among the thousand or so people employed by the Imperial Household Agency are the staff that keeps the palace grounds clean and tidy, the people who cook and serve Imperial meals and prepare state banquets, court musicians who play traditional gagaku music, gardeners, bonsai tree caretakers. poets, stablemasters, archers, guards and practitioners of traditional crafts. Nearly all of them are men.

The Imperial Palace still employs an official falconer. Falconry was a popular sport with emperors, shogun and daimyos The official Imperial cormorant fishermen wear grass skirts, blue tunics, straw sandals and pointed cap that looks like wizard’s caps. They catch trout-like ayu in the Nagar River in the Gifu area. Considered a springtime delicacy, the fish are transported by train to Tokyo and eaten only a few hours after they were caught.

Many of the traditional jobs are supervised through the Special Ceremonies Department of the Imperial Household Agency. Many employees follow in the steps of their fathers, grandfathers and great grandfathers. One gardener told National Geographic, "It is an honor for us to be here." A musician said, "it’s my fate. I was born to it."

The head grave keeper of the Mausoleums and Tombs division of the Imperial Household Agency is in charge of taking care of the Takaya no Yama ni E no Misagi Imperial mausoleum in Kirishima, Kagoshima Prefecture. The 54,000-square-meter mausoleum — 1.2 times the size of the Tokyo Dome — is said to be the resting place of Hokohohodemi-no-mikoto, a mythological figure also known as Umihiko, the grandfather of the first Japanese emperor, Emperor Jimmu. The grave keepers duties are sweeping fallen leaves and removing dirt after heavy rains. The present grave-keeper Shinichi Iwamto told the Yomiuri Shimbun , “People might thinks its funny, but I’m proud of the job I do as grand chamberlain of the deceased.” His family has taken care of the grave for five generations.

Japanese Court Musicians

Court musicians are officially known as "maintainers of a significant intangible cultural asset." They play gagaku music at official lunches, diners and public events. Robert Poole wrote in National Geographic the "shrill pipes and silk strings sounded like something made more for gods than mortals.”

When performing gagaku musicians sit cross-legged on a raised dais, all wearing identical costumes and play highly formalized music, which "blends together with stunning timbres and harmonies." The chief court musician said, "It takes about seven years of apprenticeship" to learn the whole repertoire by heart. "That is so we can play it in the dark" when some court ceremonies take place.” Hideki Togi, a handsome gagaku musician who left his place as a court musician at the Imperial Place to put out New Age records, said, "As a member of the Imperial Ensemble he was a civil servant, and my hours were set from 9 to 5 and there were a lot of ceremonial occasions."

Gagaku musicians begin studying after graduating from high school. During their rigorous seven year apprenticeship they learn to play several ancient instruments, and to sing and dance traditional music. They also learn to play Western instruments because foreign dignitaries at the Imperial Palace are often entertained with Western classical music

Some gagaku musicians come from families of musicians that trace their ancestry back to the Nara period (710-794). Only men are allowed to play in the ensemble. The chief court musician said, "I'm afraid that the family tree is dying...My family has been doing this for 500 years, since they came from China." He said the tradition couldn't continue because he three daughters and only males can carry on the tradition.

Japanese Imperial Horses

The horses that pull the lacquered Imperial carriages are Cleveland Bays, large muscle-bound animals that look somewhat like Clydesdales. The stablemaster at the palace told National Geographic they are of uniform size and color "so they do not stand out, Any with white spots or other distinguishing features are not brought in."

On of the primary duties of the Imperial horses is to provide transportation for new ambassadors from Tokyo Station to the Imperial Palace for a palace ceremony in which the ambassador presents his credentials to the Emperor. The horses are specially trained to remain clam in the midst of Tokyo traffic.

The carriages are driven by men in plumed hats and knee breaches. After arriving at the Imperial Palace, the new ambassadors are greeted by the Grand Master of Ceremonies and escorted down a red carpet.

Cremation Eyed for Emperor, Empress

The Imperial Household Agency is considering cremating the bodies of the Emperor and Empress after their deaths, to respect their wishes for a simple funeral, agency chief Shingo Haketa said. The Emperor and Empress have both expressed a wish to be cremated "to minimize the impact on the lives of citizens," Haketa said at a press conference. [Source: Jiji Press, April 27, 2012]

“In ancient times, Japanese emperors and empresses were buried after death. Cremation took place for the first time in the early eighth century and became common around the middle of the Muromachi era (1336-1573). Burial replaced cremation in the middle of the 17th century and has been the norm since then.

“The agency is also considering the possibility of placing the ashes of the Emperor and Empress in the same tomb following cremation. It will spend about a year deciding on the details of their funeral services, such as where and how they will be carried out. It is unusual for the agency to comment on the funeral of a living Emperor or Empress. The Emperor and Empress have "repeatedly expressed their opinions on the subject," Haketa said, adding that discussions are long overdue.

The government decided to spend about 189 million yen for the funeral and grave of Prince Tomohito of Mikasa, who died last week at the age of 66 after a long battle with cancer. The government will allocate 131 million yen from reserve funds to cover funeral-related expenses. It will seek funds for constructing his grave under the fiscal 2013 budget. The overall spending of 189 million yen will be almost the same as that for the prince's youngest brother, Prince Takamado, who died in 2002 at age 47. [Source: Jiji Press, June 13, 2012]

Image Sources: Imperial Household Agency, Japanese government, 2) Emporer at Parliament, Getty Images, 3) Ise, Yamasa

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2012