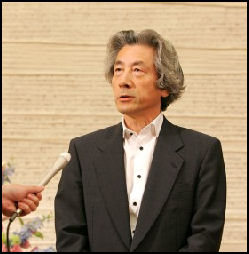

JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI

Junichiro Koizumi took office in April 2001 and vowed to make "structural reforms without sacred cows" and make the kind of hard decisions necessary to turn the Japanese economy around. His views and his aims were often in opposition to those of the LDP, which at one point he declared he was going to “destroy.”

Koizumi was the only Japanese named in Time magazine’s 100 “Shapers” list in 2006. Ian Buruma wrote that the “most interesting thing about” him “is that he is interesting” and then called him “a good-looking, straight-talking maverick.” Koizumi made many changes: he brought Japanese politics out of the backroom and into the public; scored election victories by appealling directly to the electorate rather than party bosses; and made a sincere effort to reform discredited government policies but in the end was able to achieve much less than what he wanted.

Anthony Failo wrote in the Washington Post, Koizumi “took his light saber to practically every national taboo. He cut through the country’s notorious bureaucratic fat...Where his predecessors had used pork in vain attempts to drag the nation out of its decades-long recession. Koizumi turned to market forces...When China’s looming emergence as a superpower began to cast a long shadow over Japan, Koizumi charted a new course for a bolder nation.” And “he did so with a flair that Japanese had never before seen in a politician.”

Koizumi served for 5½ years. He retired in September 2006 according to party term limits. He was the longest serving prime minister in a generation and the third longest serving in the postwar era. He was still popular when he stepped down. The jury is still out on his long term strong impact on Japan. Was he an initiator on the road to change, or was he just an aberration.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MODERN HISTORY factsanddetails.com; JAPAN BECOMES AN ECONOMIC POWERHOUSE IN THE 1970s AND 80s factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BUBBLE ECONOMY IN THE 1980s AND ITS COLLAPSE IN THE 1990s factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND ITS PRIME MINISTERS AND GOVERNMENT IN THE 1990s AND EARLY 2000s factsanddetails.com; SHINZO ABE'S FIRST STINT AS PRIME MINISTER, YASUO FUKUDA AND TARO ASO factsanddetails.com; DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF JAPAN (DPJ) WINS BIG IN 2009 ELECTION IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; JAPAN'S DECLINE factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Government Profile kantei.go.jp and kantei.go.jp ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; New York Times articles nytimes.com ; Yasukuni Shrine homepage yushimatenjin

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Koizumi Diplomacy: Japan's Kantei Approach to Foreign and Defense Affairs” by Tomohito Shinoda Amazon.com; “Japan's Dysfunctional Democracy: The Liberal Democratic Party and Structural Corruption” by Roger W. Bowen (2002) Amazon.com; “The Bubble Economy: Japan's Extraordinary Speculative Boom of the '80s And the Dramatic Bust of the '90s” by Christopher Wood Amazon.com; “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John Dowser of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1999. Amazon.com; “Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power” by Sheila A. Smith (2019) Amazon.com; “Japan in Transformation, 1945–2020 by Jeff Kingston Amazon.com

Koizumi's Life

as a young lawmaker Koizumi was born on January 8, 1942 in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture into a political family. His father and grandfather were both members of the Diet. His mother and sisters were regarded as skilled political insiders. His grandfather was a postal minster and successful campaigner for universal suffrage, His father was an orphan who eloped with his grandfather’s daughter. After a rocky period the grandfather adopted him and aided his political career. Koizumi’s cousin was a kamikaze pilot who flew his plane into an American ship in the final months of World War II.

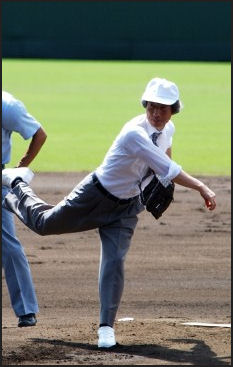

Koizumi graduated with a degree in economics from Keio University and studied at the University of London. He is fluent in English and likes pro wrestling and kick boxing and heavy metal music by groups such as X Japan. Before he was prime mister he traveled on ordinary trains and often did his own shopping by himself. He also attended kabuki performances and watched movies in cinemas by himself.

Koizumi is remembered for his long, wet-looking, curly, grayish hair, whose curls and sheen were achieved with quarterly perms and the liberal use of Buri Kon blue conditioner (actually Alberto VO5 Consort gel made under a Japanese license). Koizumi started a website called “henjin” (“weird” or “eccentric”) after his hairstyle and took dance lessons from Richard Gere.

While serving as Prime Minister, Japanese learned his barbers name, (Teruo Nakagomi), his blood type (A), his favorite historical figure (Winston Churchill), his favorite actor (Gary Copper) and his favorite punk song (Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young” done by X-Japan). While serving as prime minister he listened to classical musical, slept for five hours a night and often spent hours lying awake thinking..

Koizumi shares the same birthday — January 8th — with Elvis Presley and is a big fam of the American singer. Shortly after taking office in 2001 he lent his name to an album with 25 Elvis songs entitled “Junichiro Koizumi Presents My Favorite Elvis Songs”. The record sold over 150,000 copies. It is said that the Elvis song that Koizumi like to sing most in karaokes is said to be “I Want You, I Need You, I love You”.

Koizumi's Unusual Family Life

Koizumi was married in 1978, during his second term in the lower house. He was 36. His wife, Kayoko Miyamoto, was a 21-year-old college student and daughter of the chairman of a major drug company. Their first date lasted an afternoon and an evening and Koizumi proposed the next day. Four months later they were married.

The meeting was arranged by then-Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda and the wedding dates were set to meet his schedule. Over 2,500 people attended the wedding. The wedding cake was shaped like the Japanese Parliament building. Koizumi’s wife later told the Asahi Shimbun "I did not known know anything about him...I had heard he had a large stack of photographs of prospective brides, so I thought it was a real honor just to be chosen by him."

Koizumi was divorced in 1982 when his wife was six months pregnant. His wife said he was very busy and had little time for her. He said afterwards, "I always say that you need 10 times more energy to go through a divorce than you need for a marriage. The suffering and anguish is even greater when children are involved. I never want to go through that again. For this reason I will likely never marry again." He never did remarry and became extremely close with his unmarried older sister, Nobuku, who brought up his two older sons and acted as his private secretary. He had no known girlfriends or affairs after he split from his wife even though many women considered him very sexy when he became prime minister.

Koizumi has three sons. The two that were born during his marriage were raised his sister Nobuko after the divorce. His wife was not allowed to see them even though she requested to see them several times. Miyamoto said that Koizumi had promised that she could see her two older sons when they were in middle school. "Koizumi is a man who keeps his promises," she said. "But on this point he did not."

Koizumi's third son, Yoshinaga Miyamoti, was born after the divorce. Before and while he was prime minister Koizumi paid child support but never visited him even though he lived less than an hour from his home. After his father was elected, Miyamoto cheered during televised political rallies, kept a picture of the prime minister on the wall of his room and said he wanted like to meet his father.

Koizumi's Political Career

Fukada was like mentor and father for Koizumi, who was elected to the lower house in 1972 from the a district in Kanagawa and was reelected more than 10 times. He served as health and welfare minister in 1988, telecommunications minister in 1992, health and welfare minister again in 1996.

Koizumi ran for LDP president two times earlier: in 1995 and 1998 and lost. In 1995, he ran on a reformist platform but lost by a wide margin to Hashimoto. He ran again in 1998 and lost by a wide margin again.

Koizumi was regarded as a outspoken and direct loner. He disliked conspiring, deal making and making decision by consensus building. Instead he has tried to appeal to grassroots sentiments. His closest aides throughout his career were his mother and sister.

Koizumi as Prime Minister

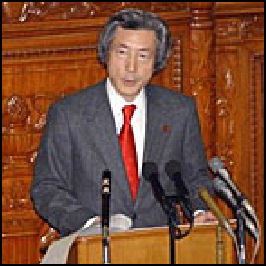

Koizumi was very popular. His approval ratings were often above 80 percent in his first year in office. After taking office the first time he appointed a cabinet with five women, including the outspoken Makiko Tanaka as foreign minister, and Heizo Takenaka, an anti-bureaucrat scholar, as the architect of his economic policy, and other outsiders. Their average age was 4.6 years less than the cabinet of his predecessor. His criticism of politics as usual and calls for reform and outsider stance were seen as breaths of fresh air into the stagnant system

Koizumi's cabinet At first Koizumi had a personal touch. Japanese cheered his pleas for reforms during his speeches. Young fans screamed and wore T-shirts with his face. Posters and pictures with his image sold out at stores. He lived modestly, dressed causally in the summer to encourage people to cut air conditioning use and appeared at meet and greets. He held of the hand of Hiroshima atomic blast victims. His son appeared in beer commercials. A lot of this seemed staged for television.

Despite his casual style Koizumi often, at least tacitly, supported a conservative agenda that included : 1) a privacy protection bill and other legislation to muzzle the press; 2) legislation to beef up the military, that included sending Japanese troops abroad and respond to military emergencies; and 3) issuing school textbooks with a nationalist slant. Koizumi also called for direct elections of the prime minister and supported laws that were passed to give Japan's military a more prominent role in international affairs.

Later Koizumi seemed distant, out of touch and even irrelevant. He failed to confront problems and move decisively. Tanaka and some other appointments proved to be embarrassments. When he talked it often seemed like he had nothing to say and seemed like he was a slave to system like predecessors. He made promises but failed to deliver on them and was famous for giving vague stock responses rather than answering questions or addressing complex issue in detail. Still Koizumi had a way of coming off as confident and self-assured even when he spouted out drivel and non-answers.

Koizumi had few friends and many enemies and ignored the factions. He relied on his popularity with the public to battle and overcome rather work with his own party. Under Koizumi there was a breakdown in the faction system as members of factions voted to support Koizumi rather than their faction leaders.

Koizumi Reform Drive

The LDP won a landslide victory in upper house elections in 2001. This was viewed as mandate for Koizumi and his planned reforms. The slogan for the campaign was "Let's change."

Koizumi promised to change the LPD's traditional pork barrel politics, privatize state monopolies, eliminate bridges-to-nowhere public works projects and liquidate bad bank loans. He talked about diverting tax revenues earmarked for road construction to other purposes; said he would find money for the pension and health care systems; and said regional government should decide which projects should be built rather that the national government.

Koizumi pledged to make four major reforms: 1) reform the pension system, which was stressed from a rising elderly population and declining revenues: 2) reform local government’s fiscal conditions: 3) reform the four road-related public corporations: and 4) privatize the three postal systems. Koizumi also promised abolish or privatize public corporations such as the postal services savings system that have underwritten much of the economic activity in the 1990s but were very unprofitable.

Koizumi cut state pensions, raised health insurance premiums, and changed laws to allow companies to hire more temporary staff in lower wages. Heizo Takenaka, Koizumi’s economy czar, led a tough but successful effort to clean up the economy and change the way of doing business. His greatest success was cleaning up the banking system. Takenaka was unpopular with industry leaders, bureaucrats and lawmakers and was accused of running the show with a “dictatorial” governing style and not compromising or even consulting with the groups affected by the decisions he made.

Obstacles to Koizumi Reforms

Most of the efforts to thwart Koizumi’s reforms came from within the LDP and the bureaucracy by old timers who were linked with construction and real estate interests and wanted to protect their pet projects and their supporters. People in Hokkaido, which receives the largest proportional share of of government revenues for construction projects, were particularly upset about the reforms.

The construction industry that Koizumi said he wanted to dismantle was in many was key to keeping the LDP in power. When a government advisory panel on privatizing public highway operators called for strict limits on the construction of new highway its chairman resigned and walked out. Some pundits said if Koizumi went through with his reforms he would dismantle the LDP the same way Gorbachev dismantled the Soviet Union.

Effectiveness of Koizumi Reforms

Some progress was made. Koizumi managed to pass legislation that reduced government payrolls and significantly cut public works spending. In fiscal 1998 the central government spent about ¥15 trillion on public works projects, By fiscal 2005 that figure had been reduced to ¥8 trillion. While largess to rural areas continued the tap was tightened from 6 percent of GDP to 4 percent.

Despite progress, unprofitable companies and banks were bailed out, the national debt rose and pork barrel politics continued, although a shadow of its former self. Koizumi’s plans to make regional government more effective was stymied by local bureaucracies and “road to nowhere” public works projects continued.

The economy did improve significantly under Koizumi’s leadership and free market policies. Many give credit to Koizumi fr making Japan and Japanese companies leaner and meaner and more competitive but also criticized him for increasing the gap between the rich and poor, creating an underclass of part time and temporary workers that were poorly paid and easy to fire and undermining Japan’s traditional egalitarian ethos. See Economics, Economic History, Economic Recovery.

See Postal Reform Below

Koizumi and Yasukuni Shrine

Koizumi angered many people in Asia by making a visits to Tokyo’s Yasukina Shrine, which contains memorials to World War II war criminals, and not taking action against controversial textbooks that glossed over atrocities committed by Japan in World War II. In 2001, twenty young South Korean chopped their tips of little fingers to protest Koizumi's vis to Yasukuni Shrine.

Yasukuni Shrine was built in 1869 under the Emperor Meiji. It memorializes almost 2.5 million Japanese, including women and children, who died in wars since 1868. The overwhelming majority — about 2.1 million — died in World War II. What makes the shrine so controversial is the fact that it honors hundreds of convicted war criminals, including 14 so-called Class A criminals, such as executed war-time leader Hideki Tojo, the prime minister who authorized the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Their spirits have been "enshrined" there since 1960s and 70s. Shrine organizers stress that many thousands of civilians are honored. China and South Korea however see the shrine as glorification of Japanese atrocities. The 14 "Class A" war criminals were the men who ordered and oversaw Japan’s brutal war in China and South East Asia, which left millions dead and included widespread massacres of civilians, rape used routinely as a weapon and the use chemical and biological weapons by the Japanese against civilians. [Source: BBC, Washington Post] See Yasukuni, Places, Tokyo .

Koizumi visited Yasakuni Shrine every year while he was prime minister. He was the first prime minister to make the visit since ultraconservative Yasuhiro Nakasone did in 1985. Koizumi said he visited the shine only to pray for peace and often did it in conjunction with a strong antiwar message. Although he said his visit were “personal” he often signed the registry as the Japanese prime minister “I don’t go there for the war criminals,” he said. “I go there to mourned the many who made sacrifices.” His cousin was a kamikaze pilot.

Koizumi visits to Yasakuni Shrine were formally supported by the LDP in its policy platforms and played well with conservatives who saw the visits as acknowledgments of sacrifices made by brave men for their country. In April 2006, 96 lawmakers, 87 of them from the LDP, visited the shrine.

In Japan, there was strong opposition to the shrine visits and many viewed them as unnecessarily provocative. Even some conservative members of the LDP and representatives of families of war dead expressed concern. In September 2005, a high court in Osaka ruled that Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine were illegal and unconstitutional because they violated rules on the separation of state and religion. The suit was brought by a group of 188 plaintiff, including Taiwanese families that said the shrine visits by Koizumi caused them mental pain and suffering. Their demands for compensation were rejected.

Documents released in July 2006 revealed that even Emperor Hirohito — the Emperor of Japan during World War II — was displeased about the enshrinement of the war criminals and felt that visits to Yasukuni Shrine were inappropriate. In diaries of private conversations, Hirohito said he stopped visiting the shrine when it began honoring 14 convicted Class war criminals, including Hideki Tojo, the wartime prime minister, and others who were executed. Hirohito visited the shrine eights times after the end of World War II. His last visit was 1975. Neither he or the government explained why he stopped the visits. The current emperor, Emperor Akihito, never visited the shrine as Emperor.

Koizumi and Foreign Policy

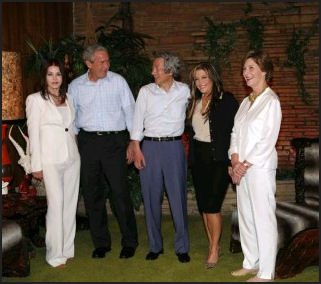

Koizumi at an offiicial White

House dinner with the Bushes Under Koizumi, Japan became very close to the United States, sending troops to Iraq, but more distant from China and South Korea. See International

On September 17, 2002, Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited Pyongyang, North Korea. The visit lasted only a few hours. Koizumi arrived at Pyongyang around 9:00am. He met with Kim Jong Il for one hour in the late morning. Kim was described as stiff and nervous. He didn’t welcome Koizumi with same open arms he did when he met with South Korea President Kim Dae Jung. Koizumi and Kim had lunch separately and had a second round of talks, for 1½ hours, in the afternoon. After giving a press conference alone, Koizumi flew home.

There were hopes that the meeting would lead to solutions to many of the problems that exist between Japan and North Korea. But the visit ended up creating more problems than it solved A joint declaration signed by both leaders called for the resumption of talks on the normalization of diplomatic relations between to the two countries. Kim Jong Il promised a moratorium on the provocative missile tests and promised to let weapons inspectors into the country and offered a “candid apology” for the abductions and said “this will never happen again.” But the statements did little to dispel the outrage over the issue. See Abductees, North Korea, International

In August 2005, Koizumi offered another apology for Japan’s actions in World War II, saying, “Our country has caused tremendous damage and pain to the people of many countries, especially in Asian countries, through colonial rule and invasion. Humbly acknowledging such facts of history, I once again reflect most deeply and offer apologies from heart.” After saying this he prayed at a National Cemetery rather than Yasukina shrine and called on China, South Korea and Japan to work together “in maintaining peace and aiming at development in the region.” These efforts did not draw nearly as much attention as his Yasukuni Shrine visits.

Koizumi and U.S. President George Bush were on very friendly terms. Knowing that Koizumi was a big Elvis fan, Bush and his wife accompanied Koizumi for a private tour Graceland, where the Japanese leader met Elvis’s wife Priscilla and his daughter Lisa Marie While singing the lines “Hold me close, hold me tight” from his favorite Elvis song “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You” You, Koizumi puts his arms around a surprised Lisa Marie. Koizumi and Bush sang the song together and Bush gave the Japanese leader a CD of Elvis classics and a vintage jukebox. In a speech Koizumi said, “Thank you very much American people...I got “Love Me Tender”.”

Japanese Election in 2003

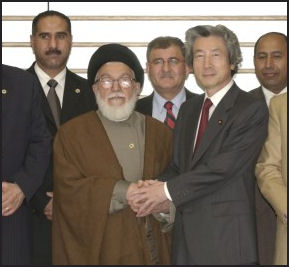

with the leader of Iran In 2002, the left-center Minshuto (Democratic Party of Japan), the main opposition and the party of Naoto Kan, merged with left-leaning Jiyuto (Liberal Party), headed by Ichiro Ozawa. In September 2003, Koizumi was reelected as the LDP president by members of his party. Not long afterwards he sang some Elvis Presley songs with the actor Tom Cruise and took a risk and called early elections.

In the November 2003 elections, Minshuto did surprisingly well. It increased its number of seats in parliament from 137 to 177 (a gain of 40 seats) while the LDP decreased its number of seats from 247 to 237 (a loss of 10 seats). The election made Minshuto into a political power to be reckoned with and effectively gave Japan a two party system.

The LDP stayed in power by forming a coalition with the New Komei Party (a party affiliated with a religious cult). After the election Hoshushinto (New Conservative Party) disbanded and its four members joined the LDP. This gave the LDP 241 seats. The LDP-New Komei coalition had 275 (13 less than it had before). After the election three independent legislator joined the LDP, giving it 244 seats and the LDP-New Komei coalition 278 seats.

Lower House (seats after November 2003 election): LDP (237); Minshuto (177); New Komeito (34); Japan Communist Party JCP (9); Socialist Democratic Party, SDP (6); Hoshushinto (4); Other parties (13). Voter turnout was about 60 percent, lower than 63 percent in 2000. The LDP coalition won 275 seats.

Lower House (before the 2003 election): LDP (247); Minshuto (137); New Komeito (31); JCP (20); SDP (18); Hoshushinto (9); Other parties (13). The reason the LDP had more seats than it did after the 2000 election is that many candidates who were elected as independents in 2000 joined the LDP. The LPD, New Komei and Hoshushinto coalition had 287 seats.

Lower House (seats after 2000 election): LDP (233); Minshuto (127); New Komeito (31); Jiyuto (22), JCP ( 20); SDP (19); Hoshushinto (7); Other parties (21).

Consequences of the Election in Japan in 2003

The election was seen as a triumph for Minshuto, but a somewhat muted one considering that most of the seats it picked up were from other left-leaning parties such as the Japan Communist Party (JCP) and Socialist Democratic Party (SDP). The election was a disaster for the JCP, SDP and Hoshushinto. The SDP lost two thirds of seats (from 18 to 6). Takado Doi , Japan’s most well-known female politician, lost in humiliating fashion to an LDP rookie but kept her seat through party representation. The JCP lost more than half its seats (from 20 to 9). And Hoshushinto lost more than half its seats (from 9 to 4).

Analysts interpreted the election result as a sign that the public had reservations about Koizumi’s policies and they doubted his ineffectiveness in bringing about the reforms he had promised. The narrow victory dealt a blow to his efforts to get rid of the opponents to reforms because he needed them to hold onto power in the LDP.

The 2003 election ushered in a period in which Japan essentially had a two party system with the LDP and the Minshuto Hidekazu Kawai, a professor of politics at Gakushuin University told the New York Times: “This election is a watershed in the postwar history of the country because, first, there was an electable opposition and, second, the parties talked about policies. For the first time, voters could chose the prime minister.” In a poll after the 2003 election, 69 percent of the respondents said they viewed a two part system favorably.

Minshuto was stronger in urban areas and among younger people while the LDP was strong in rural areas and among older people. After the election Kan took the roll of an opposition leader criticizing things the ruling government did after they did it, In May 2004, Kan resigned after admitting he had not paid his public pension premiums.

Politics and Pensions and Screw Ups By the Japanese Opposition

In 2004, failure to make pension payments, due primarily to the complicated and confusing payment system, led to the down fall of several top politicians. Koizumi failed to pay pension dues for a total of seven years. His infarction were deemed minor and not a big issue was made off it.

Several other top LDP members, whose failure to pay was deemed more serious, were forced to resign. Opposition leader Naoto Kan used the pension issue to gain political capital until it was revealed that he too didn’t pay all that he should have and he too was forced to resign. Several other opposition part members also were forced to resign. Most said their failure to pay was unintentional. The revelation occurred just as the parliament was talking up the issue of pension reform.

The DJP was led after Kan’s resignation and before the September 2005 election by Katsuya Okada, a handsome but uncharismatic figure who resigned after the 2005 election because of the DJP poor’s showing.

Postal Reform Before Elections in 2005

Koizumi’s primary reform goal was to overhaul Japan Post, Japan’s postal system. In the early 2000s, Japan Post was Japan’s largest employer with 400,000 employees, 25,000 outlets nationwide, almost the number of all of Japan’s bank branches combined, and had assets of $3.1 trillion. It was the nation’s main lender and insurer, with $1 trillion in life insurance policies, and effectively the largest savings bank in the world. It was a source of funds for wasteful public works projects and funds used by LDP politicians to support their patronage systems.

In September 2004, a plan was adopted to split Japan Post into four firms for 1) mail delivery, 2) savings, 3) life insurance and 4) post office network management under a holding company in September 2007.

Koizumi had called for a review of the postal services way back in 1992 in his first news conference as posts and telecommunications minister and raised postal privatization as an issue when he ran for LDP president in 1995. In his first address to the Diet as prime minister he called for privatization of the postal services.

Postal Reform Politics

In August 2005, Koizumi dissolved the lower house parliament and called an early election after rebels in his own party in the upper house rejected his postal reform bills by a vote of 125 to 108, with 30 LDP members either voting against the bill or abstaining. The bill only passed through the lower house by five votes a month before. The move was unusual in that Koizumi dissolved the lower house over a vote in the upper house.

Koizumi’s initial postal reform bill was significantly watered down. To get the bill passed Koizumi made a number of compromises such as failing to impose penalties against those who broke the rules of the reforms. Koizumi also forced members of his own party to accept other unpopular changes such as cuts in public spending. His strategy was to force the LDP to accept the changes by raising the threat that he might resign and the party could lose power without him.

The elections were a risky move and regarded as referendum on the postal reform bill. To counterattack the LDP postal “rebels” — 37 lower house members who voted against the postal bills — Koizumi struck them from lists of LDP candidates and fielded “assassins” to take their place. The opposition was caught off guard and had a difficult time developing a strategy. If they went against Koizumi they were seen as objecting to reform.

Japanese Elections in 2005

In elections in September 2005, the LDP gained 84 seats and won an overwhelming 296 seats in the 480-seat lower house. With the 31 seats from its coalition partner, the New Komeito Party, it held 327 seats, more than a two thirds majority.

The opposition won only 134 seats — 113 for the DPJ (down from 177 before the election), 9 for JCP, 7 for the SDP, for the PNP and 1 for the NPN. Independents, many of them postal rebels, took 18 seats and Shinto Daichi took 1.Voter turnout was 67. 2 percent, up from 59.9 percent in the last election in 2003.

The victory was a mandate for Koizumi and his reforms and was seen as a sign that the public supported his postal reform drive. The stock market shot up to a four year high. The yen increased in value. The victory was also a crushing defeat for conservatives in the LDP and liberals in the opposition. New LDP members that defeated postal rebels were described as Koizumi’s kids. A couple of them were pretty women who received some media attention.

After the Elections in Japan in 2005

In October 2005, after the election Koizumi reshuffled the cabinet appointed three possible successors to key pots: Taro Also as Foreign Minster; Sadakazu Tanihaki as Finance Minister and Shinzo Abe as Chief Cabinet Secretary. Only two women were in the cabinet.

In October 2005, the postal privatization bill was enacted after its passage in the lower house, by 200 votes, and in the upper house. Many the postal rebels who voted against the bill before the elction and won back their seats voted for the bills after the election. In December 2006, the postal rebels that won their seats back as independents were allowed back in the LDP.

In May 2006, a reform bill backed by Koizumi was submitted to the Diet. It called for: 1) reductions of the total number of government employees by 5 percent, 2) reform of the government-affiliated finance institutions, 3) review of independent administrative organizations and 4) the integration or abolishment of government financial institutions.

Koizumi’s successor’s failed to do much to further his reforms

DPJ After the Elections in 2005

Koizumi at Graceland

with the Bushes and

the daughter and former

wife of Elvis Presley After the election in September 2005, the DPJ selected a new leader, Seiji Maehara. He defeated Naoto Kan 96-94 in a hastily-prepared party vote. He is a Kyoto native and a foreign and security policy expert and won his parliament seat five times,

In March 2006, Maehara quit and other party leaders resigned over a scandal involving fabricated e-mail involving DJP lawmaker Hisayasu Nagata who used a fabricated e-mail to falsely accuse LDP Secretary General Tsutomu Takebe of receiving ¥30 million from former Livedoor President Takafumi Horie. Nagata was kicked out of Party he was the forth consecutive DPJ president to reign before completing his term.

In April 2006, 63-year-old Ichiro Ozawa became the DJP leader after easily defeating Kan in a party poll 119-72. Ozawa had been the leaders of othe parties: the Japan Renewal Party, the New Frontier Party and the Liberal Party. Ozawa named Kan as his deputy president.

Ozawa is a former secretary general of the LDP. He defected from the LDP in 1993 to a play a key role in the creation of the Cabinet of Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa, the first non-LDP administration since 1955. Ozawa has been called the “Destroyer” and “Party breaker “ because of his habit of forming parties only to have them merge with other parties.

In September 2006, Ozawa was hospitalized for 10 days after experiencing chest pains.

Koizumi Resigns

Koizumi resigned as prime minister in September 2006. He remained active in the Japanese legislature working for road reform and visited Yasukuni shrine in 2007 after he was Prime Minister.

In September 2008, at the age of 66, Koizumi suddenly announced his retirement from politics effective the next election. He backed his second son 27-year-old Shinjuro to take his seat. It was not exactly clear why he decided to suddenly retire. Many thought t was because the inauguration of Taro Aso as prime minister, heralding a return to the bad old days before the Koizumi reforms.

After Koizumi the LDP had so many leaders who resigned in disgrace it is hard to keep track of them all.

Image Sources: Kantei, office of Japanese Prime Minister

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016