DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF JAPAN (DPJ) WINS BIG IN 2009 ELECTION IN JAPAN

Hatoyama In August 2009, the Democratic Part of Japan (DPJ) won a landslide victory in lower house general elections against the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). It was a historic event in that the LDP had held power for all but 11 months since it was created in 1955 and had defined Japanese politics and governance in that time. No other party had held a majority in the past-war era. What was particularly humiliating for the LDP was that it was thrown out in such an overwhelming way.

The relatively liberal DPJ took 308 of 480 seats in the lower house and the conservative LDP took 112 seats. Before the election the DPJ had only 112 seats and the LDP had 303. Other parties held 53 after the election compared to 63 before. The New York Times reported: "The Liberal Democrats had governed Japan for most of its postwar history, but in recent times the party appeared unable to adapt to a changing era. Disgruntled voters increasingly blamed them for failing to outgrow traditional pork-barrel politics and find an end to the nation's seemingly intractable political paralysis and its economic decline in the current recession."

On election night roses were placed in the boxes of winning candidates in DPJ headquarters in Tokyo. When the counting was down the wall with boxes was filled with roses. Among the LDP candidates that lost were ex-Prime-Minister Toshiki Kaifu, who lead Japan from 1989 to 1991 and served in the lower house for 49 years and was re-elected 16 times.

After the victory DPJ leader Yukio Hatoyama said, the election represented “the first-ever proper change in government in the history of our constitutional politics...It has taken a long time, but we have at last reached the starting line...This is by no means the destination...We were given an incredible number of seats, but this doesn’t mean we feel mandated to deal with things forcefully and hastily. We should cast away any sense of arrogance from the size of our victory.”

The DPJ victory meant that a two party system in Japan was for real. The feeling was that at last Japan would become a full-functioning democracy rather than a de-facto one-party state run by bureaucrats. Plans to expand the welfare state ran head in into a stagnant economy and gigantic debt.A New York Times editorial read: “It took Japan decades, but voters finally got fed up with the entrenched ruling clique and threw it out office, The landslide victory for the Democratic Party of Japan was the first defeat for the Liberal Democratic Party in more than 50 years. We hope this stunning rout presages the end of economic decline and political stagnation, but that will take real leadership, not just trading one group of politicians for another.”

Taro Aso took responsibility for the LDP loss and quit as LDP president. With many family ties to the party — including his father founding it — Hatoyama said that he hoped the LDP would resurrects itself. If it dies then Japan would no longer have a strong two-party system.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MODERN HISTORY factsanddetails.com; JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI factsanddetails.com; SHINZO ABE'S FIRST STINT AS PRIME MINISTER, YASUO FUKUDA AND TARO ASO factsanddetails.com; NAOTO KAN, THE LEADER OF JAPAN DURING THE MARCH 2011 TSUNAMI factsanddetails.com JAPAN'S DECLINE factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Government Articles kantei.go.jp ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; New York Times articles nytimes.com ; Hatoyama Speech huffingtonpost.com ; List and Links to Government Agencies on Adminet admi.net/world/jp ; Nakasone on Hatoyama New York Times ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Japan's Dysfunctional Democracy: The Liberal Democratic Party and Structural Corruption” by Roger W. Bowen (2002) Amazon.com; “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John Dowser of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1999. Amazon.com; “Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power” by Sheila A. Smith (2019) Amazon.com; “Japan in Transformation, 1945–2020 by Jeff Kingston Amazon.com

Details of the 2009 Election

with Boy Scouts The lower house was dissolved on July 21, 2009. The campaign officially kicked off on August 18. The election was held on August 30. A total of 1,374 candidates ran for 480 seats — 300 seats in single-seat constituencies and 180 seats chosen by proportional representation. It was the 45th general election since World War II and the first since 2005.

During the campaign Aso and Hatoyama both took to the streets with clusters of microphones in their hands, addressing supporters. In its manifesto the DPJ promised all kinds of things to all kinds of people and promised to deliver them soon. It also linked itself with Obama optimism and tied the LDP to Bush’s aggressive international programs and failed economic ones. Aso attacked Hatoyama by asking him how he expected to pay for all the generous policies he was proposing. Hatoyama responded by cutting wasteful LDP programs.

Forty-six percent of the DPJ diet members who were elected in 2009 were first time members of parliament. Many had little political experience. Some didn’t even know much about the structure of the diet or how bills were passed.

A record 54 female candidates won seats. Of these 40 were from the DPJ. The total is up from 43 successful candidates in the general election of 2005. In the 2009 election the DPJ chose female candidates to run against LDP heavyweights. Among those who were victorious were Ai Aoki, who defeated the leader of the New Komeito Party and Eriko Fukuda who beat former defense minister Akio Kyuma. Before the election the DPJ had only 10 female lower house members.

Voters voted the way they did not so much because they embraced and had great affection for the DPJ but rather because they disliked the LDP and had had enough of they way it ran Japan. A survey by the Yomiuri Shimbun taken immediately after the election found that 48 percent of those who voted for the DPJ said they did so because of discontent with Prime Minister Taro Aso and the LDP. Thirty-seven percent said they voted for the DPJ because they wanted change. Only 10 percent said they voted for the DPJ because of its policy stances. In addition 44 percent said they didn’t think the DPJ would achieve its promises. Only 25 percent said they thought the DPJ would head Japan in the right direction.

2009 Election Numbers

Of the 1,374 candidates who ran for office in the 2009 election, 1,139 ran for the 300 single seat constituencies. Of these 653 were “dual candidates” who ran in both the single sea races and the proportional representation system. A total of 235 ran only in the proportional representation system. The DPJ fielded 330 candidates; the DPJ, 328.

The DPJ formed a 319 seat coalition with the Social Democratic Party, which won seven seats, the People’s New Party, which won three seats, and the New People’s Party, which won one seat. A total of 241 seats is needed for majority. Some asked why it was necessary for the DPJ to form such a coalition in that it already had a big, majority and political demands made by the small parties were so divisive. The primary reason was that votes from those parties was necessary to pass legislation through the upper house.

The LDP lost of total of 181 seats from what it held before the election. Its coalition partner, the New Komeito Party, won 21 seats down from the 31 it heldbefore. Together they held 140 seats, down 191 seats from the 331 they held before the election. Other parties that won seats included the Japan Communist Party (JCP, nine seats) and Your Party (five seats). Independents and minor parties won seven seats.

Yasuhiro Nakasone and Joseph Nye on the DPJ Government

On the new DPJ government coming to power former prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, arguably Japan’s most revered elder statesman, told the New York Times the end of the Liberal Democrats’ half-century of governing was a national opening on par with the wrenching social and political changes that followed defeat in the war. He praised the appearance of a strong second political party as a step toward true democracy but warned his countrymen to keep a careful eye on a rising China and for the DPJ to not alienate Washington, its protector and proven friend. He also said he wants Japan’s conservatives to pick up the pieces from their defeat. “FoR the development of Japan’s democracy, I did not think it was good for the Liberal Democratic Party to last forever, or for it to be a permanent ruling party. Being knocked out of power is a good chance to study in the cram school of public opinion.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, January 29, 2010]

Martin Fackler wrote in New York Times that Nakasone said the path to a more equal Japan lies with the United States, not apart from it. He also faulted Mr. Hatoyama for giving Washington the impression that he valued ties with China more than he did those with the United States.”Because of the prime minister’s imprudent remarks, the current situation calls for Japan to make efforts to improve things,” he said. The relationship with the United States is different from that with China, he said, because “it is built on a security alliance, and not just on the alliance, but on the shared values of liberal democracy, and on its shared ideals.” These shared values should be enough to bind the United States and Japan together even in tough times.

Harvard professor Joseph Nye told the Daily Yomiuri, “I think it is healthy for any democracy to have changes of political parties...But it’s also true that if you have a change of parties after such a long period and people have not had experience in government, that is natural that there be a certain amount of learning and a certain amount of turmoil.”

YUKIO HATAYAMA

with a bonsai tree Yukio Hatoyama officially became Prime Minister on September 16, 2009 when he was voted in as prime minister in the Diet by the lower house. He was selected as one the world’s 100 most influential people in 2010 by Time magazine but his moment in the sun didn't last long. Hatoyama only served 8½ months (266 days) as prime minister, the sixth shortest under the current Constitution.

Hatoyama has been nicknamed the “the extraterrestrial” in Japan — a reference to his wide-set, bulging eyes, protruding forehead and his erratic plus his sometimes flaky behavior and the strange things he sometimes says and does. Hatoyama has described his main political principal as “fraternity.” Some see him as genteel and idealistic; others see him as “weak an indecisive.”

In a survey by the Yomiuri Shimbun in February 2010, Hatoyama was No. 1 among the 480 lower house members in asset holdings with assets valued at ¥1.64 billion (around $18 million). His brother Kumio ranked No. 2 with about ¥816 million. The Hatoyama’s family assets are said to be worth ¥1.44 trillion (about $16 billion).

Yukio Hatoyama’s Political Family

Hatoyama comes from a blue-blooded political family that goes back five generations. His grandfather Ichiro was prime minister of Japan from 1954 to 1956 and the first LDP President. He was well known for his power struggles with Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, the father of former Prime Minister Taro Aso. Hatoyama and Yoshida’s battles were legendary and they split Japan’s conservative block following World War II. Ichiro Hatoyama (1883-1959) restored diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union in 1956.

During World War II Ichiro Hatoyama served as education minister and clashed with Prime Minister Tojo on government policy. For a time he lived in exile in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture, where he heard the Japanese Emperor announce Japan’s surrender. While there he read extensively from a book about “fraternal revolution” by the Austrian diplomat Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, who also influenced his grandson and his dream of a united Asia.

After World War II, Ichiro Hatoyama founded the Liberal Party and was expected by many to become prime minister. However, he was purged from the government by the American occupiers on the grounds that his activities in the diet during the war raised some questions.

Yukio Hatoyama’s father Iichiro was foreign minister from 1976 to 1977. His younger brother Kunio is a parliament member with the LDP and served as Internal Affairs and Communications minister in 2008 and 2009 until he was forced to resign because of a scandal. Hatoyama’s great grandfather Kazuo was the Imperial Diet lower house speaker from 1896 and 1897. His grandfather on his mother side was the founder of Bridgestone. Consequently his mother is very rich.

Yukio and Kunio Hatoyama are said to be on fairly good terms. In 2008, they opened a private school with Hatoyama in its name. In a speech in 2009, Yukio said, “Though belonging to different parties, my brother and I are on good terms at the end of the day.”

Kunio Hatoyama entered politics immediately after graduating from university. He has been elected to the lower house 11 terms, during which time he held cabinet posts such as labor minister and education minister. He served in the Aso cabinet and is regarded as one of the richest men in the Japanese government. Among his assets are an apartment and villa in Tokyo and 3.75 million shares of the Bridgestone stock.

Hatoyama’s Life

with Asashoryu Yukio Hatoyama graduated from Tokyo University with a degree in engineering. Afterwards he did some research work at Stanford University and earned a PhD. He worked for a while as an assistant professor in Senshi University’s business administration department.

Hatoyama’s family was surprised that he went into politics. His mother once said, “I always thought he would become a scholar because all he did was study” when he was young. “Since his kindergarten days, [Hatoyama’s little brother] Kunio often said he wanted to become a politician and prime minister, Yukio used to look disgusted at such remarks, putting on a face that seem to say, “Kunio’s opened his big mouth again.”

Hatoyama once regarded himself as a singer. He recorded a record in the 1980s that became something of a collectors item after he became prime minister. For a while he ran an izakaya pub called Tomato in the Shimbashi, a district in Tokyo where salarymen like to party. When he was a diet member he visited the pub once a week, donned a happi coat and served drinks and talked politics with the customers. Hatoyama’s partner at the izakaya said, “even though its not strange for a politicians to prioritize promoting themselves, Hatoyama has devoted himself to being a good listener and asking people, “How’s your work?” The partner said Hatoyama remained calm when drunk customers became belligerent and argued with him.

Before he became prime minister Hatoyama lived in the Den-en Chofu area of Tokyo. He is said by friends to be fond of shopping and taking walks with his wife, and is sometimes spotted holding her hand. Hatoyama once remarked, “My wife is the sun.”

Hatoyama’s son Kichiro graduated from Tokyo University with a degree in engineering and is an urban engineering researcher and lecturer at Moscow State University. Yukio Hatoyama’s beloved golden retriever died on the day he was named prime minister.

Hatoyama’s Mother and Wife

Yasuko Hatoyama was the eldest daughter of Shojiro Ishibashi, the founder of tire maker Bridgestone Corp. She was also the wife of the late Foreign Minister Iichiro Hatoyama, the oldest son of Ichiro Hatoyama, the first president of the Liberal Democratic Party. Famed for her family’s vast wealth, including her shares in Bridgestone, she was known to have supported the political activities of her oldest son, Yukio, and Kunio, an LDP Lower House member who had served in Cabinet posts, including the education and justice portfolios. She died in February 2013 at the age of 90. [Source: Kyodo, February 13, 2013]

In 1996, Yasuko Hatoyama was said to have encouraged her two sons to establish a political party, a suggestion that led to the foundation of the precursor of the Democratic Party of Japan. As DPJ leader, Yukio Hatoyama served as the country’s prime minister from September 2009 to June 2010.

While serving as prime minister, one of his campaign funding bodies was accused of having fictitiously listed donors, for which his chief accountant was sacked and convicted. It was later revealed that Yasuko Hatoyama had been providing Yukio Hatoyama with ¥15 million per month for seven to eight years. According to 2011 income reports and other sources, Yasuko Hatoyama gave ¥4.2 billion in cash, equities and real estate to each son.

Hatoyama’s wife Miyuki has gotten some attention in the press for her gregariousness and unconventional views. Not shy about expressing her quirky spirituality, she has claimed to have known Tom Cruise in a previous life and says that she starts each day by “eating the sun.” When she eats the sun she closes her eyes and grasps imaginary pieces from the sky and places them in her mouth and goes “yum, yum, yum.” She told the Los Angeles Times, “I get energy from it. My husband also does this.” [Source: John Glionna, Los Angeles Times]

The Guardian described Miyuki as a “gloriously eccentric foil to her humdrum hubby.” She was once a singer-dancer in an all-female review and in a previous marriage was married to a Japanese restauranteur in California. Among the professions and interests ascribed to her are “life composer,” or lifestyle guru, macrobiotics enthusiast, cookbook author and “fearless clothes horse.” On top of that she can do a reasonably good Michael Jackson moon walk and has made clothes from hemp coffee bags.

Miyuki is older than Hatoyama. She met him will she was working at her first husband’s restaurant and he was a student at Stanford. Her books include “Top of Form Bottom of Form Miyuki Hatoyama’s Spiritual Food”, “Miyuki Hatoyama’s Have a Nice Time” and “Amazing Events I Have Encountered”. The latter is about a journey to alien world Miyuki took before she met Hatoyama.

In “Amazing Events” Miyuki wrote, “While my body was sleeping, I think my spirit flew on a triangular-shaped UFO to Venus. It was an extremely beautiful place and was very green.” Her book editor told the Los Angeles Times “It was just a vivid dream...She does like spiritual topics. She says things like, “If you’re with me, it won’t rain.” She can be misunderstood.”

Kichi Nakano, a political scientist at Sophia University, told the Los Angeles Times, “There were some rumors about her eccentric behavior, and she does seem a little unusual for a Japanese woman her age. I don’t think any of this matters as long as it stays clear of issues regarding public policy.” Rather than being embarrassed that his wife has been labeled as a “fruitcake” Hatoyama has said he admires his wife’s “vivacity.”

Hatoyama’s Political Career

The Hatoyama family is deeply rooted in the Otowa district in Bunkyo Ward, Tokyo yet Yukio won his seat in Hokkaido Constituency No. 9 and his brother Kunio won his in Fukuoka constituency No. 6.

Hatoyama serves as a parliament member from a district centered around Muroran in Hokkaido. He is considered a parachute candidate who has lived mostly in Tokyo and has little connection with the local people in his district.

Hatoyama didn’t enter politics until he was 39. He ran for lower house election in 1986 as an LDP candidate and won on his first attempt. At that time he belonged to the faction led by Prime Minister Kakuey Tanaka.

When Hatoyama was a junior lawmaker Yomiuri Shimbun journalist Koichi Akaza said he muttered “so indistinctly that I could hardly hear a word he said” at press conference and when Akaza did hear “he talked in such a circuitous way that I could not make sense of what he was saying...I concluded that Hatoyama probably just did not have the aptitude to be a politician, and I was actually quite bewildered as to why he had entered politics at all.”

Hatoyama left the LDP in 1993, disgusted by a string of corruption scandals, and formed the New Party Sakigake (Pioneers) with Masayoshi Takemura and other lawmakers. On the decision Hatoyama said, “leaving the Liberal Democratic Party wasn’t a question of like or dislike. I realized the nation’s politics took root.” He helped create Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa’s coalition government in 1993 and served as chief cabinet secretary in the Hosokawa administration.

In 1994 the New Party Sakigake joined a coalition government with the LDP and the Japan Socialist Party. In 1996 the precursor of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was founded with 57 members . Hatoyama left his party in 1998 when and joined the DPJ when it merged with three other parties and Naoto Kan was their president. The DPJ increased its seats in the 2000 election and expanded further in the 2003 election after merging with the Liberal Party.

In September 1999, Hatoyama was named as the first DPJ president after the DPJ was created. He was forced to step down in 2002 to take responsibility for confusion within the party over a failed merger, weakened leadership and personal affairs. He regained the post of DPJ President in May 2009 after his predecessor Ichiro Ozawa was forced to step down over an illegal campaign contribution and Hatoyama defeated Katsuya Okada in a party election 124-95. Hatoyama and Okada were both former party presidents. Hatoyama immediately seized the initiative and called for an election and was aggressive in his head-to-head debates with Prime Minister Aso, in which both seemed to put more emphasis on attacking the other than solving Japan’s problems. When Hatoyama took over the approval rating for the DPJ was 30.8 percent , compared to 28.4 percent for the LDP.

Hatoyama Government

In his first major policy speech in October 2009 Hatoyama emphasized the historic significance of his party’s victory and called it “bloodless reformation.” “The current reformation,” he said, “restores sovereign power to the people, breaking from a system dependent on the bureaucracy. It is also an attempt to transform the very shape of our nation from a centralized state to one of regional and local sovereignty and from an insular island to an open maritime state.”

Weakening the power of the bureaucracy was a primary goal of the Hatoyama government . In an effort to achieve this it dissolved the old institutions of unelected officials that resolved policy disputes behind closed doors and took away the bureaucrats right to draft budgets, one of their key sources of power. One of the key differences between politicians and bureaucrats is that politicians can be voted out of office while bureaucrats can’t.

The Hatoyama government has looked to Britain, with its strong prime minister and cabinet, as a model. Several key advisors to Hatoyama traveled to London to study the British parliamentary system.

The chief members of the Hatoyama government members are: 1) Naoto Kan, Finance Minister; 2) Katsuya Okada, Foreign Minister; 3) Seiju Maehara, Construction and Transport Minister; and 4) Zhizuka Kamei, a former LDP member who at named State Minister in charge of Financial Services and Postal Reform. Kan was appointed Finance Minister after his predecessor at that post quit because of poor health. He started out in the Hatoyama government as Vice Prime Minister, the head of national strategy and Internal Affairs and Communications Minister.

The two women ministers in Hatoyama’s government are Mizuho Fukushima, head of Social Democrat Party and State Minister in charge of Consumer Affairs and Declining Birthrate; and 2) Keiko Chiba, the Justice Minister.

Ozawa, See Below

The DPJ, which controlled 323 seats, was pushed around by its coalition partners the Social Democratic Party and the People’s New Party — which respectively had only 12 and eight seats — on issues like American military bases and postal reform with the Social Democratic Party opposing the American military presence in Japan and the People’s New Party calling for an end to postal reforms made by the Koizumi government. Some asked why it was necessary for the DPJ to form such a coalition in that it already had a big, majority and the political demands made by small parties were so divisive. The primary reason was that votes from those parties was necessary to pass legislation through the upper house.

Hatoyama as Prime Minister

debating in the Diet Hatoyama was very visible as prime minister. He presented the Emperor’s Cup to sumo wrestler Asashoryu after he won a sumo tournament in Tokyo and appeared in a fashion show with his wife, wearing an outfit you would normally associate with a slapstick comedian.

“Fraternity” was Hatoyama’s primary ideological keyword. He told the Washington Post, “If you look at Japan today, I feel that this spirit of fraternity is lacking. That is what I am advocating the change were need to revive fraternity...Politics should pay a greater rile on behalf of humanity or the weak.” Hatoyama has been influenced by Count Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894-1972), a half-Austrian, hall-Japan philosopher who was a major proponent of European-Union-like integration in the first half of the 20th century and a believer that a “spirit of fraternity” could advance the world beyond capitalism and socialism.

The approval rating of the Hatoyama cabinet was 71 percent in October 2009, a couple months after the elections. By December its approval rating had dropped to 55 percent. Former Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone likened Hatoyama’s leadership and his ideas about fraternity to “soft ice cream”’sweet and delicious at first, but quickly melts and disappears.

Hatoyama’s main problem was that there so many strong, diverse and often contradictory views within his government and it was difficult to shape them into a coherent policy without angering key members of his government. Often it seemed that Hatoyama wasn’t up to the job of being a strong leader able to navigate through messes and make tough decisions.

Hatoyama’s Domestic Policies

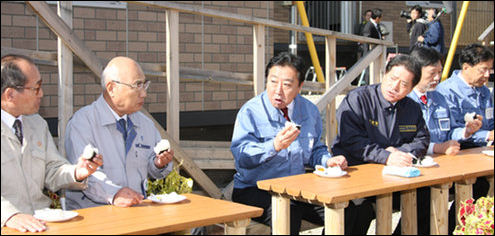

visiting a drug factory To achieve his goal of setting up a government in which politicians ran things rather than the bureaucrats, Hatoyama established a national strategy bureau, whose first order of business was suspending the implementation of the fiscal budget of the LDP and freezing or canceling many LDP programs.

Among the issues taken up by the DPJ were the creation of more day care centers to meet a need created by shortage of them and increase government payments to parents with children. Under the DPJ plan families would by given ¥26,000 a months for each child until they graduated from middle school. Under the old system a payment of ¥10,000 was given to children under three and ¥5,000 was given to children between three and sixth grade of primary school. The child allowance was taken as a gift. It did little to stimulate the economy. Many felt the money could be put to better use building more day care centers and other facilities for children. In any case the program was expensive and depleted the government treasury and raised the government debt.

In September 2009, Hatoyama announced that Japan would aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent from 1990 levels by 2020. Quake-proofing work deemed needed at 2,800 schools was postponed to free up funds to make high school education effectively free. Koizumi’s postal privatization policy was dealt a set back. Rather than dividing Japan Post into four separate entities for 1) postal service, 2) banking, 3) insurance and 4) network, the network and service units were merged.

Among the DPJ’s biggest problems was dealing with costly promises made during the election such as getting rid of expressway tolls which would derive the government of desperately needed funds, encourage people to drive more and cause traffic jams on the expressways. On the issue of health care the DPJ vowed to end a new scheme for “late-stage elderly people” that required them to pay more but was put in place to trim health care debt and reduce the burden paid by future generations.

The DPJ ultimately had difficulty coming up with funding and had to renege on some of it promises. Taxes were down as a result of the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009. Some reforms were delayed. Plans to reduce the gasoline tax — a campaign pledge — were scrapped and the gasoline tax was kept at the same rate.

The Hatoyama government introduced a subsidy system for farmers that many criticized for not achieving its aims — chiefly to provide more income for farmers and better food security for Japan — and for taking money out the hands of people and organizations that really need it. Like the child allowances the program was expensive and depleted the government treasury and raised the government debt.

Efforts to Cut Public Works Programs Such a Yamba Dam

Cutting expensive public works projects that were deemed a waste of money was high priority of the new Democratic Party of Japan government that came to power in 2009.

The project that got the most attention form cost cutters was the $4.6 billion Yamba dam in Gunma Prefecture, an expensive project that was launched in 1952 and had few benefits other than flood control and providing water and irrigation to an area near Tokyo that didn’t really need it. The only problem was that $3.2 billion had already been spent on it, hundreds of people had already been relocated and the project was 80 percent done. Eighty-seven local dam projects were examined with the government freezing 48 out if 56 projects currently being carried out. In December 2009, 30 dam projects were singled out for close scrutiny with the aim of closing down ones deemed unnecessary.

In December 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “After more than two years of turmoil, the government has finally settled the issue of whether to cancel or resume construction of the Yamba Dam in Gunma Prefecture. Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister Takeshi Maeda has at last decided to resume construction of the dam in Naganoharamachi. The government will earmark costs for building the main structure, funds for which had been frozen, in the fiscal 2012 budget. The decision was based on a reexamination of the project by the ministry, in which it judged "construction of the dam is most desirable" in terms of flood control and water utilization effects as well as project costs. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, Dec. 23, 2011]

“Under the slogan "from concrete to people," the Democratic Party of Japan included cancellation of the Yamba Dam project in its manifesto for the 2009 House of Representatives election, which brought about the DPJ-led administration. Seiji Maehara, now the DPJ's Policy Research Committee chair, became infrastructure minister after the 2009 election. Based on the manifesto's promise, he forcibly terminated the dam's construction without any consultation with local governments involved.

“In the face of strong opposition by residents and local governments, then Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister Sumio Mabuchi in autumn 2010 effectively nullified Maehara's decision on the project. Subsequently, the ministry had been reexamining the project to decide whether the dam should be constructed.

“Already 80 percent of the total project costs have been spent on related works, such as construction of roads to replace ones that will become unusable. If the project had been axed, the government would have had to return funds to Tokyo and five other prefectures of the Tonegawa basin, which had paid out more than half of these costs.

“Since the Democratic Party of Japan came to power in 2009, infrastructure ministers have decided to continue 14 and suspend six of the 83 dam projects reviewed by their ministry and related municipalities. The ministers' decisions on the 20 projects have matched the conclusions of the reviews. The Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry is still reviewing 63 dam projects. The Yamba Dam case was the only one in which the ministry and the DPJ had disagreed. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, December 24, 2011]

Japanese Inquisition

Hatoyama set up the Government Revitalization Unit that was in charge of identifying and cutting wasteful spending in the government. Resembling a cross between a Congressional budget hearing and a Spanish Inquisition interrogation, the hearings werw conducted by the units panels and were often short and harsh. Bureaucrats and supporters of projects deemed wasteful by the panel were given about 30 minutes to an hour to justify their programs and asked questions by a panel that often had little knowledge of the programs.

The hearings were conducted by 13-member panels and were shown on television. One of the reasons for having them was to make government more transparent. In one widely shown exchange the head of a project to build an advanced supercomputer was asked to offer some good reason why the government should fund the project. The project head said to advance science and compete with the United States. The head of the panel responded by saying, “Does it matter if the United States is No.1" and refused a request to increase funding. Scientists, including some Nobel laureates condemned the cuts, arguing the money was vital for Japan to remain competitive in technology fields.

The panels racked up about $8 billion in budget cuts, about half of what they had hoped to achieve. Among the program that were cut back were subsidies for herbal medicines, grants to science programs to make carbon nanotubes and jet-engine rockets, funding to help new businesses, requests for more military personnel, and requests by local government for help paying for higher teacher salaries and children reading programs. Among the projects that were drastically cut were “landscape creation costs” and a planed anime hall of fame.

A second more mild round government of hearing was held in April 2010. Among the main targets in addition to wasteful spending was cushy jobs for retired bureaucrats. After four days of questions and testimonies, the government panels decided to ax 34 projects and scaled down dozens of others. Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times: “Seeking to bring its spiraling debt under control, Japan has undertaken an unlikely exercise: lawmakers are forcing bureaucrats to defend their budgets at public hearings and are slashing wanton spending. The hearings, streamed live on the Internet, are part of an effort to tackle the country’s public debt, which has mushroomed to twice the size of Japan’s $5 trillion economy after years of profligate spending.”[Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, April 28, 2010]

Hatoyama and the DPJ said their intent was to wrest control of Japan’s economy from the country’s powerful bureaucracy. “We want the public to see how their tax money is really being spent,” said Yukio Edano, the state minister in charge of administrative reform, who is heading the effort. “Then we will bring about big changes.” “Budgets have always been drafted behind closed doors, with nothing to underpin how much should be spent or why,” said Hideo Fukui, a professor of law and economics at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo. “Until now, nobody knew how unscrupulous the spending was.”

“Many analysts say that Japan must slash wasteful spending and start cutting its public debt to avert the interest rate and refinancing risks that have wreaked havoc in Greece,” Tabuchi wrote. “Addressing Japan’s debt crisis was among the many promises made by Mr. Hatoyama, Mr. Hatoyama’s Democratic Party has also been keen to find extra money to pay for an ambitious social agenda, including cash payments to families with small children and free public high school education.:

The public interest in the budget hearings has been among the few bright spots for Mr. Hatoyama... At the central Tokyo site for the hearings, people lined up to watch the bureaucrats being pressed before panels of lawmakers and appointed experts. “The bureaucrats looked scared,” said one attendee, Kenji Nakao, a 67-year-old Tokyo retiree. “It was very satisfying to see.”

Second Inquisition Targets the Bureaucracy

Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in the New York Times: “The target of the most recent hearings...is Japan’s web of quasi-government agencies and public corporations — nonprofits that draw some 3.4 trillion yen ($36 billion) in annual public funds, but operate with little public scrutiny. Critics have long argued that these organizations, many of which offer cushy executive jobs to retired public officials, epitomize the wasteful spending that has driven Japan’s public debt to dangerous levels. The daily testimony by cowering bureaucrats, covered extensively in local media, has given the Japanese their first-ever detailed look at state spending. So far, viewers have looked on in disbelief over the apparent absurdity of some of the government spending.” [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, April 28, 2010]

“In one example scrutinized on Tuesday, the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, which is government financed, spent 130 million yen ($1.4 million) last year on a 3-D movie theater used to show footage of scenery from the countryside. The movie dome, which also plays recordings of chirping insects and babbling streams, is closed to the public and is used to study how the human brain reacts to different types of scenery, said Takami Komae, head of the organization’s rural engineering department. The findings will be used to help rural areas think of ways to attract more tourists, he testified.”

Politicians ridiculed the project. “The dome is located in the countryside anyway, isn’t it?” said Manabu Terada, a Democratic Party lawmaker, at a public hearing in Tokyo. “Can’t we just step outside and see the real thing?” At the end of the hourlong hearing, all financing for the dome’s upkeep was canceled and the organization was urged to sell the facility off to salvage some of the construction cost.

Amakudari Scrutinized

Under particular scrutiny at the hearings have been the retired ministry officials who take comfortable positions at the government-linked organizations in a practice known as “amakudari,” or “descent from heaven.” The network of government-linked organizations is complex, including 104 large organizations supervised directly by the government and 6,625 smaller public corporations. Critics say that many of the former bureaucrats use their connections in government to win public money for dubious construction and research projects, then delegate the work while their organizations pocket much of the budget as administrative fees. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, April 28, 2010]

Aki Wakabayashi, an author and former worker at a government-supported labor think tank, has been one of the most fervent critics of government spending on these organizations. In 2001, she blew the whistle on her institute, describing lavish foreign “research? trips for the former bureaucrats leading the institute — complete with first-class air travel and stays in five-star hotels — and clerks who drew researcher salaries while spending their days chatting and reading magazines. “The Japanese public is angry and demoralized,” said Ms. Wakabayashi, who has been advising the Democrats on the cost-cutting panels. “And Japan’s finances are in tatters. We either fix this, or Japan goes bankrupt.”

Criticism of the Hearings

The hearings have drawn criticism from some circles. During the recent ones, members of Japan’s scientific community warned that steep cuts in research financing would damage Japan’s global competitiveness. Their fears were exacerbated when a Democratic lawmaker, known only as Renho, called for reduced spending for a government-financed project to build the world’s fastest computer, asking, “What’s wrong with No. 2?”

Meanwhile, the scale of the cuts — which will amount to a few trillion yen at best against Japan’s budget of 207 trillion yen this year — is too small to make much of a difference, some experts say. Even supporters like Ms. Wakabayashi doubt that the Democrats, with strong links to labor unions, will cut too deeply into the estimated tens of thousands of workers at the government-associated entities. [Source: by Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, April 28, 2010]

Some organizations, meanwhile, are making last-ditch efforts to drive home their relevancy. In a hastily called press conference this month, the government-financed Fisheries Research Agency announced that it had succeeded for the first time in fully cultivating Japanese eels, a fish whose breeding habits had long baffled scientists. Kiyoshi Inoue, executive director at the agency, stressed the importance of the achievement. “These findings are at the cutting edge of global research,” he told reporters.

Futenma Base Issue

After the Hatoyama government was elected in August 2009 a big deal was made the plan to relocate the U.S. Marine’s Futenma Air Base in Okinawa, which local people objected to because it was the source of so much noise. According to the plan, agreed upon by Japan and the United States in 2006 before Hatoyama took office, the flight operations of Futenma’s noisy helicopter facility would be moved a coastal area of Camp Schwab in Nago, a less populated part of Okinawa and 8,000 Marines would be moved from Okinawa to Guam.

According to the deal much of the base at Nago would be made on land reclaimed from the sea to minimize the impact on residents. Among the biggest objectors to the deal were residents of Nago and environmentalist who opposed the effect of construction on sea life in the area. Among those upset by the delay of the move were people that lived around Futenma.

There is strong opposition to the Futenma base and the deal made with the Americans by leaders of the small political parties that formed a coalition with Hatoyama’s party. Mizuho Fukushima, the female leader of Social Democratic Party, a coalition partner in the Hatoyama government, was among the most vocal and unyielding of the opponents of the base.

The government of U.S. President Barack Obama put strong pressure on the Hatoyama government to abide by the agreement struck before Hatoyama took office. The issue caused considerable strain between the government of Japan and the United States. Diplomatic dinners were canceled. Promises were broken. At one point U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton summoned the Japanese ambassador in the middle of a huge snowstorm to express her displeasure at they way events had unfolded. The New York Times said that Japan-U.S. relations were at their “most contentious” since the trade wars in the 1990s. When Defense Secretary Robert Gates bluntly demanded that Japan live up to its side of the bargain some Japanese viewed the message as “openly hostile.”

Among the ideas that were floated as alternatives to the base but were ultimately abandoned for lack of support was combining Futenma with Kadena Air base or moving the base to Shimojishima Island about 280 kilometers southwest of Okinawa or even Guam, proposals that had been rejected in earlier negotiations. The issue became further complicated in January 2010 when a new mayor was elected to Nago that opposed the base.

One suggestion was to put the base on Tokunoshima Island, Kagoshima Prefecture . About 15,000 protestors on the island showed to voice their opposition to that plan. The intensity and scope of the protest were something that had not been before.

Hatoyama originally said he would make a decision on the matter before the end of 2009 but postponed the decision until May 2010. In the meantime the United States said it would not aggressively pursue the matter. On the issue, Joseph Nye, a professor of international relations at Harvard, told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “My impression is that has to do with upper house elections...that it is a political situation where you have domestic politics determining the agenda...But I don’t think it’s going to determine the long-term future because we have such strong national interests in common.”

By April 2010, Hatoyama’s approval rating had dropped to 33 percent and half of those interviewed in Japan said he should resign if the Futenma Air base issue was not solved.

Hatoyama Scandals

Hatoyama promised to bring cleaner government to Japan and reduce corruption but had trouble keeping his own house in order. In October 2009, Hatoyama’s political management fund admitted making false reports in regarded to ¥350 million, listing donations from people who had actually not given any money, including some who were dead. A month later it was revealed that Hatoyama initially failed to declare ¥72 million in income from stock sales in 2008 but later corrected the failure and paid the tax.

The biggest embarrassment was a donation of more ¥1.1 billion to Hatoyama’s political organization over about six years by Hatoyama’s mother. The money was handed over in cash in monthly installments of ¥15 million in violation of tax and political donations laws. Hatoyama insisted that the money was a loan even though there was no documentation to say that it was. In one speech, Hatoyama said, “All of you think I must have been aware of the funds [from my mother], don’t you...I was totally unaware however.” He later promised to pay ¥400 million “gift tax” on it.

Hatoyama’s brother Kumio said, “My elder brother visited our mother frequently to ask for money, saying he needed it to distribute it and funnel it to his sidekicks — and he received it. Our mother phoned me asking “if I’m doing the right thing.”

In April 2010, an inquest panel concluded it would not be appropriate to indict Hatoyama over the false records on political donations by his fund-management organization on the grounds of insufficient evidence. In December 2009, Hatoyama’s former first secretary and another former aide were indicted for falsifying reports to disguise funds given to Hatoyama by his mother as income from individual donations and sales of tickets at find-raising parties. Prosecutors decided not to indict Hatoyama. After the announcement of the arrests Hatoyama made a deep bow of shame and shed some tears at a hastily-arranged press conference. The aide, Keiji Katsuba, was given a two-year suspended sentence for faking political fund reports.

In February 2010, an LDP politician accused Hatoyama of being “king of tax evasion” — an allusion to donations from his mother being a way to get around paying taxes. Taxes are not levied on political funds transferred between politician’s political fund-management organizations. Sometimes lawmakers use the rules to transfer political funds to their children tax free.

Hatoyama’s Resignation

Hatoyama resigned in June 2010 to take responsibility for his administration’s failure to resolve the confusion over the plan to relocate the Futenma air base on Okinawa. People had been calling for his resignation for months. There was a sense of relief that it finally happened. According to a Yomiuri Shimbun survey held a week or so before 89 percent of respondents said they “no longer trusted” Hatoyama and the approval rating of his cabinet was only 19 percent. When Hatoyama resigned so too did Ozawa as secretary general of the DPJ.

In a speech before members of both Diet houses, Hatoyama said, “The public gradually stopped listening [to me]. It’s quite regrettable, and this resulted from my lack of virtue, I’d like to step down.”

The Futenma issue had come to a head when Hatoyama was forced to sack Social Democratic Party (SDP) leader Mizuho Fukushima from his cabinet and the SDP quit the DPJ coalition after Fukushima refused to endorse the Hatoyama government decision to move the bases within Okinawa as was originally planed. Hatoyama said, “I must take responsibility for pushing the SDP into taking the difficulty decision to leave the coalition.” Fukushima was adamantly against the base in Okinawa , and refused to budge in the issue, and failed to offer an alternatives.

After he stepped down as prime minister Hatoyama said he would retire from politics then retracted his statement and said he would. He continued to stir up trouble and make confusing, irresponsible statements after he resigned. In reference to the deterrent provided of the U.S. Marines in Okinawa as reason to move Futenma Airbase Hatoyama said in February 2011 it was “an expedient excuse” — undermining the foundation of the presence of the United States in Japan.

Hatoyama Visits Iran in 2012 and Retires from Politics

In April 2012, former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama visited Iran despite government pressure to call the trip off. Hatoyama met with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his aides in Tehran to discuss Iran's controversial nuclear development program. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, April 11, 2012]

According to an Iranian report on the talks, Hatoyama criticized the International Atomic Energy Agency for applying double standards toward certain countries, including Iran, saying such treatment was unfair. At a press conference in the Diet building on Monday following his return home, Hatoyama denied making this comment, saying he profoundly regrets what he called a "complete fabrication" by Tehran. Later Tehran said they misquoted Hatoyama and apologized.

Explaining why he took the trip Hatoyama said that his trip "is part of my activities I'm making in a personal capacity as a legislator, as there is a significant possibility diplomatic efforts by an individual legislator could help the national interest." Chief Cabinet Secretary Osamu Fujimura said: "We continued to ask him not to make the trip at this sensitive time, even as an individual lawmaker acting on his own accord.”

In November 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Hatoyama announced his retirement from politics amid a feud over key issues with the current leadership of the ruling Democratic Party of Japan. Hatoyama, 65, apparently decided to retire after the DPJ decided not to give official backing to party members in the upcoming election unless they promise to follow its current policies, including a consumption tax increase and Japan's participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade talks. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 22, 2012]

Hatoyama has voiced opposition to those policies. He voted against bills for the tax hike in the lower house in June with other DPJ opponents, many of whom later left the party, including former DPJ President Ichiro Ozawa. Hatoyama has criticized Noda for pushing ahead with the tax increase plan by working with the opposition LDP and New Komeito.

A grandson of former Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama, Hatoyama earned a Ph.D. in engineering at Stanford University and started an academic career. He changed course, however, and first won a lower house seat in 1986 as a member of the LDP and has been reelected to the chamber seven times. He left the LDP in 1993.

Hatoyama’s Legacy

Henshu Techo wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “I think he is a tender-hearted person. Perhaps his ardent desire to please those around him by any means led him to promise the relocation of the U.S. Marine Corps' Futenma Air Station in Okinawa Prefecture to the U.S. president. He also pledged a relocation of the base "outside the prefecture" to the people of Okinawa Prefecture. Consequently, his words proved to be sinful lies to both parties and caused fissures in Japan-U.S relations. [Source: Henshu Techo, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 22, 2012]

I think he is a rare individual. There is no comparable figure among all the prime ministers before or after him. After he left the prime minister's post, he was criticized for visiting Iran in defiance of the government's opposition. The visit did a lot of harm and no good whatsoever. While there is no shortage of those ill-suited to serve as prime minister, this is the first example of someone who could not even serve properly as former prime minister.

I would like to take up one particularly impressive specimen from among Hatoyama's many quotations. At the time of the Democratic Party of Japan's presidential election two years ago, Hatoyama embarked on a "coordination" effort to avoid a collision between Naoto Kan and Ichiro Ozawa. It ended in failure, serving only to muddy the waters. At that time, he spoke to his close aides in embarrassment saying, "What on earth was I doing?" A fitting title for your memoirs, Mr. Hatoyama, if ever you write them.

NAOTO KAN

Kan talking to a

Japanese astronaut In June 2010, after Hatoyama resigned Naoto Kan was named the president of the DPJ and became the prime minister of Japan and the fifth Japanese leader in four years. In his first press conference Kan said, “the main role of politics is to create a society with the “least unhappiness...We will build a strong economy, strong government finances and strong social security systems at the same time.” When took office Kan inherited a bunch of problems: economic malaise, corruption scandals, poor relations with the United States.

Kan had been a major political figure and opposition leader for some time. Described by the New York Times as a plain-spoken politician with activist roots, he is handsome and well spoken, and became involved in politics as a student activist and environmentalist. Nathan Gardels of Global Viewpoint wrote, “More than anyone else in Japanese politics, Kan has lead the democratic revolt of the urban consumer and citizen against the bureaucracy allied with old rural politics of the Liberal Democratic Party that ruled Japan for decades.” In the end though his policies were on the right but he lacked the leadership, political and social skills to effectivelt to sell them to the public and even many members of his own party.

Kan was 63 when he took office. Known for his quick temper, he gained national attention in the mid-1990s when, as health minister, when he exposed his own ministry’s use of blood tainted with H.I.V. He was the Deputy Prime Minister at the time of Hatoyama’s resignation. Kan became the DPJ president by defeating his only opponent Shinji Tarutiko, chairman of the lower house Environment Committee, 291-129 in the DPJ election, in which DPJ member in the upper and lower houses voted. Kan was supported mainly by groups within the party that wanted to distance themselves from Ozawa.

“Mr. Kan is the outsider-turned-prime minister who should have provided leadership,” said Takayoshi Igarashi, a professor of urban policy and a longtime friend of Mr. Kan who serves as an adviser to his cabinet. “The paralysis in Japan just keeps getting worse because leaders cannot answer the people’s expectations.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 26, 2011]

Mr. Kan was supposed to be different. In a nation where so many national politicians are second-, third- and even fourth-generation lawmakers, he was the rare self-made man. He entered public affairs four decades ago as an aide to a prominent feminist leader and rose to national attention when as health minister in the 1990s, he exposed his ministry’s cover-up of a scandal involving H.I.V.-tainted blood products.

When he became prime minister in June 2010, T-shirts appeared with the slogan “Yes, We Kan” — anticipating that he would break the mold of the ineffectual Japanese political leader and shake up the sclerotic status quo. But after only one month in office Kan’s disapproval ratings surpassed his approval ratings. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: When the March 2011 earthquake struck, "the Diet was discussing whether Kan had taken illegal campaign donations...Japanese politics had become so fractious and unstable in recent times that when the German newspaper Die Zeit produced an illustration of Kan it mistakenly featured a Prime Minister who was booted from office two years earlier.

See Separate Article NAOTO KAN, THE LEADER OF JAPAN DURING THE MARCH 2011 TSUNAMI factsanddetails.com

Ichiro Ozawa

Ichiro Ozawa was selected as the head of the DPJ in the Hatoyama government. On Ozawa’s section as party head, Hatoyama said, Ozawa’s ability to devise shrewd election tactics would be indispensable for the DPJ’s attempt to gain a working majority of seats in the upper house in next year’s election.

Ozawa was described as a “Shadow Prime Minister” or “shadow shogun.” His office was put in charge of screening all petitions from industrial associations, local governments and others. Ozawa had a hand in picking the Cabinet and coached first term representatives. Those that were late to his seminars were punished like school children. Many worried that Ozawa would take over the DPJ or divide it. Some of his allies took key positions in the government. A very close ally of Ozawa’s, 77-year-old Hirohisa Fujii, was named Finance Mister but was forced to resign only a few months after taking his post due to poor health.

Hatoyama was advised by his aides to pick cabinet members with a certain amount of distance from Ozawa and not ask permission to enact policies, simply tell him. Ozawa gave high positions in the DPJ to members of the upper house in anticipation of doing well and gaining supporters in the upper house elections.

In December 2009, Ozawa went to China, accompanied by 600 people, including 143 DPJ party members, each of whom had his or her photograph taken shaking hands with Chinese President Hu Jintao. The visit came across as a publicity stunt with no real purpose. Ozawa insisting it was part of the “Great Wall Plan” that he launched when he was a member of the LDP in the 1990s. Around the same time Ozawa drew criticism for putting pressure on the Japanese Emperor to meet the Chinese Vice President in a hastily-prepared meeting and for calling Christianity a “self righteous” religion.

After Naoto Kan became prime minister Ozawa openly criticized his remarks advocating a consumption tax and revisions of the DPJ manifesto. Ozawa’s political troubles seemed to drag the entire DPJ down. Kan hoped Ozawa would resign and asked him to step down temporarily from the party but Ozawa refused. Kan then took steps to punish him. Ozawa’s allies rebelled against this and refused top back Kan’s budget.

Ozawa and Kan thought so little of each other, the Asahi Shimbun reported, they don’t even exchange New Year’s cards — a common courtesy among Japanese and the equivalent of exchanging Christmas cards.

See Separate Article ICHITO OZAWA https://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat22/sub146/item801.html#chapter-19 factsanddetails.com

YOSHIHIKO NODA

In September, Yoshihiko Noda, a down-to-earth fiscal conservative, former finance minister and a member of the Democratic Party of Japan, was sworn in as the nation's 95th prime minister — the 62nd person to take the post and the sixth change of leaders in five years. Hiroko Tabuchi wrote in New York Times, “Mr. Noda, a surprise choice by the governing Democratic Party as prime minister, has promised a nose-to-the-grindstone approach to policy making rather than grand appeals to public sentiment. In an emotional speech before the party vote...that elevated him to the top spot, he compared himself to a hardworking loach, an unattractive, bottom-feeding yet resilient fish.” “I will stink of mud and work until I sweat on behalf of the people,” he said. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, August 30 and September 2, 2011]

Whether his self-depreciating style will charm voters remains to be seen. Analysts said his lack of recognition could work in his favor by not building up expectations in the beginning that he cannot fulfill. “He won’t start with strong approval ratings, which will put less pressure on him to deliver right away,” said Hirotada Asakawa, an independent political analyst.

Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “political analysts said his victory was as much about seeking a fresh start for the Democratic Party, which has floundered since taking power in a historic election two years ago. The choice of Mr. Noda, who has no large power base within the party and is not one of the Democrats’ founding members, appeared to signal an effort to move beyond deep divisions that have undermined the party. [Source:Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 29, 2011

“Analysts said that he may represent the last chance for the unpopular Democrats, who seemed to have lost their way under the indecisive leadership of Naoto Kan and his predecessor, Yukio Hatoyama. Mr. Noda was seen as having an opportunity to heal a deep division in the party over its scandal-tainted kingpin, Ichiro Ozawa, because he was neither a supporter nor a sharp critic of Mr. Ozawa.

The Economist reported: “Before he is dismissed as yet another has-been, at least it can be said that he has a nicely self-deprecating turn of wit. Other qualities should also be noted. Mr Noda, a former finance minister, has a keen sense of the swamp in which Japan is mired, with low growth, a national debt twice the size of the economy, an ageing population and a dwindling workforce. On top of that comes cleaning up after the earthquake and tsunami of March 11th, which destroyed a swathe of the north-east, led to a nuclear emergency and threw Japan’s energy policy into disarray. In contrast to his immediate predecessor, Naoto Kan, Mr Noda is a conciliator, both within his fractious party and towards the opposition, led by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Perhaps his greatest asset is that, commanding so little faith, he will not succumb to inflated expectations.” [Source: The Economist, September 3, 2011]

Choosing a New Prime Minister After Kan

voting for his own designation In a sign of deep divisions within the party, no less than seven candidates have put their hands up to replace him in an internal party vote. “I don’t see any of the problems changing,” said Professor Gerald Curtis of Columbia. “If anything, the next guy will be the shortest-lived prime minister yet.”

In the end five DPJ lawmakers — finance minister Yoshihiko Nada, economy and trade minister Banri Kaieda, former foreign minister Seiji Maehara, transport minister Sumio Mabuchi and agriculture minister Michihinko Kano — ran in the election among party Diet members to chose a new party leader, the de facto prime minister. The candidates — a couple of them recognizable, others no, none of them making much of an impressiont’seemed to have come out of nowhere, make a few speeches and television appearances and compete in a quickly thrown-together election in which DPJ lawmakers were the only ones allowed to vote. It seemed like the exact opposite of the long drawn-out process to choose a new president in the United States.

Former Democratic Party of Japan President Ichiro Ozawa cast a long shadow over poll.Kohei Kobayashi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “His party membership has been suspended over a land purchase scandal, leaving him with no voting rights...Ozawa still has enormous influence over the party's ongoing presidential election. About 90 DPJ members who support Ozawa met at a Tokyo hotel — before the party election. “Ozawa and former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama brought their choice for DPJ head: Economy, Trade and Industry Minister Banri Kaieda.” [Source: Kohei Kobayashi, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 28, 2011]

Ozawa told the attendees, "After consulting with Mr. Hatoyama, I decided Mr. Kaieda is the most suitable person to be our next leader." He urged the attendees to support Kaieda, but there was only scattered applause. The atmosphere was cool, with no shouts of enthusiasm. Kaieda made jokes when it was his turn to speak, but no one laughed. The most boisterous moment came during a closing speech by a junior member who said, "Let's make Mr. Kaieda the prime minister this year, and next year we should make Mr. Ozawa prime minister." The attendees immediately burst into applause and shouted, "Let's do it," three times.

Yoshihiko Noda Becomes Prime Minister

Hiroko Tabuchi and Martin Fackle wrote in New York Times,” Mr. Noda outmaneuvered more prominent rivals in an internal party ballot, making him leader of the Democratic Party, which has been plagued by internal feuding...Noda defeated the trade minister, Banri Kaieda, by 215 to 177 votes in a runoff election, after a first ballot failed to produce a clear victor from a field of five candidates.” The vote took place at a Tokyo Hotel. A total of 398 DPJ Diet members (292 from the lower houses and 106 from the upper house) were eligible to vote. Noda was formally elected prime minister by the full Parliament, where DPJ control and has the most seats in the more powerful lower house. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, Martin Fackler New York Times, August 29, 30, 2011]

Kaieda was supported by the Ozawa faction, appointed to his cabinet position by Kan and was ahead in polls before the party election. He was in first place after the first balloting with 143 votes (compared to 102 for Noda and 74 for third place Seiji Maehara) but ultimately was done in by his support from Ozawa. Anti-Ozawa votes were seen by analysts as key to Noda’s victory in the party election along with votes from Maehara and Kan supporters. Many of those that voted for Noda were fearful of the affect that Ozawa would have on the party were Kaida to win. They also worriesd that a revival of the Ozawa agenda would cause bad feelings between Japan’s political parties and within the DPJ. The last straw for many potential Kaieda supporters was when Kaieda proposed axing a deal to work together with the LDP and another opposition party.

Noda has called for unity and is expected to distribute cabinet and party posts to competitors as well as allies to underscore his conciliatory approach. During the brief campaign, Mr. Noda tried to set himself apart by displaying a sense of humor in an otherwise drab race when he compared himself to a loach. “Let us end the politics of resentment,” Mr. Noda said. “Let’s make a more stable and reliable political leadership.”

The Finance Minister under Naoto Kan, Noda is a relative political unknown. It was a surprise victory for Mr. Noda, who had been seen as running a distant third before the internal vote by the Democratic Party. During the campaign, Mr. Noda presented himself as a pro-business fiscal conservative who could rein in Japan’s ballooning national debt while also taming the soaring yen and battling deflation.

Yoshihiko Noda’s Early Life

Noda's cabinet The son of a paratrooper in the Japanese Self-Defense Force, Noda was born in 1957 in Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture. Both his parents were the youngest children from farming families in Toyama and Chiba prefectures. Noda said his parents inspired him to become a politician.At age 3 in 1960, he was watching the news of the assassination of Japan Socialist Party Chairman Inejiro Asanuma with his mother. He remembers his mother telling him at the time, "Politicians risk their lives." After that, he reportedly became interested in politics.[Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 31, 2011]

Noda is the first prime minister to attend from the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management, which was founded by the founder of Panasonic. When he was a student at Waseda University he was leaning toward a career in journalism. His father informed him that the Matsushita institute was seeking its inaugural class. The now prestigious institute has produced many politicians, but it had no reputation when Noda considered enrollment. He later said, "I felt the potential because nothing was established [at the institute]."

Soon after graduating from Waseda in the spring of 1980, Noda entered the private institute. Yasutomo Suzuki, mayor of Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, who was Noda's classmate at the institute, said he remembers that Konosuke Matsushita, founder of Panasonic Corp. who established the institute, stressed the importance of street speeches. "If you want to become a politician, can you make speeches on the street? Because if you don't have a political base, name recognition and money, you have to ask for support with only a microphone. Can you do that?" Suzuki quoted Matsushita as saying.

Jiro Ushio, chairman of Ushio Inc. who interviewed Noda as vice director of the Matsushita institute when Noda sought admission, said he remembers him well from the interview. "He was rather quiet, but was a dignified young man who looked me in the eye and listened to others," Ushio said. According to the 80-year-old chairman, Noda said he was moved by the institute's philosophy that calls on people to find and embrace their own path. "Among the many bright and enthusiastic people seeking admission to the institute, I thought we needed a person like him and decided to accept him," Ushio said.

Yoshihiko Noda’s Political Career

Noda, who lacked a political base and name recognition in his early days as a politician, is known for having stood in front of train stations to make speeches in the morning for about 25 years in his hometown in Chiba Prefecture. After marrying him, his wife Hitomi also stood before the stations with her husband and handed out fliers to passersby. This down-to-earth style played a big role in shaping the career of the man who will be Japan's 62nd prime minister.

checking typhoon damage in Nara

After graduating from the institute, Noda aimed for a Chiba Prefectural Assembly seat and started making daily speeches at local stations in 1986 to seek voters' reactions firsthand. He continued the routine until last year. "Making a street speech is a basic I learned at the institute. Noda is our role model. He's Mr. Seikeijuku," Suzuki said. The institute is called Matsushita Seikeijuku in Japanese. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, August 31, 2011]

In the 1993 House of Representatives election, Noda was elected for the first time as a member of the now-defunct Japan New Party, along with former Foreign Minister Seiji Maehara, a fellow Matsushita institute graduate. Noda moved to Shinshinto (New Frontier Party) and finally to the DPJ.

In his political life, Noda suffered some setbacks. In the 1996 lower house election, he sought his first reelection, losing by a narrow margin of 105 votes. For the following three years and eight months, he stayed away from the Diet. He carried on politis, His wife continued to help him with his political activity, folding fliers and taking telephone calls at his local office.

The low-profile Noda's popularity has fallen well short of Maehara, a favorite among voters. In political circles, however, Noda has drawn attention as a promising conservative since his early days as a politician. In 2002, Noda, only a two-term lower house member at the time, ran in a DPJ presidential election representing younger members.

Although his bid for the party presidency failed, he has since been appointed to key party positions such as Diet Affairs Committee chairman. After the DPJ took power in 2009, he raised his portfolio by serving as senior vice finance minister and then finance minister.

Noda has become one of the leading members of the DPJ and heads an intraparty group called Kasei-kai, which boasts about 25 members. Former Chief Cabinet Secretary Hidenao Nakagawa, who was Noda's Liberal Democratic Party counterpart as Diet Affairs Committee chairman, recalled: "Mr. Noda stood firm against us during Diet deliberations for bills related to [former Prime Minister Junichiro] Koizumi reforms. But he was flexible."

But when he served as the DPJ's Diet Affairs Committee chief for the second time in 2006, Noda was cornered over a fake e-mail scandal and resigned from the post, along with Maehara. Some people point to Noda's resignation as a sign of weakness.

Ushio said Noda spent a long time establishing his own political style based on various activities and experience, including morning speeches at stations, raising funds from local small and midsize companies and losing his Diet seat. "I think Japan is facing an important turning point that could determine its future. I want him to build a system that can unite Japan and fend off a national crisis by utilizing Japanese people's wisdom. I believe he can do it," Ushio added.

Yoshihiko Noda As Prime Minister

Hiroko Tabuchi and Martin Fackle wrote in New York Times, “Noda takes the post with Japan fighting to recover from a devastating earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in March, on top of an economy weakened by persistent deflation, the recent global economic turmoil and growing concerns over the country’s burgeoning debt.” [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 29, 30, 2011]

at Fukushima

“The new prime minister inherits a government that has largely lost the confidence of the Japanese people. Mr. Noda faces a gridlocked Parliament, where opposition parties have used their control of the legislature’s upper chamber to block Democratic Party policies. The Liberal Democratic Party, ousted by the Democrats in 2009, has harshly accused the outgoing administration of muddling the response to the natural and nuclear disasters.”

“Political analysts are divided on Mr. Noda’s chances of overcoming the political paralysis in Japan, which has gone through six prime ministers in five years. They said that while the choice of the relatively youthful Mr. Noda represents a much-needed changing of the guard in the governing party, he will face the same fiscal constraints and resistance to change that had stymied his predecessors.”

“One of his biggest challenges will be a divided Parliament, where opposition parties like the Liberal Democrats have used control of the upper house to block the Democrats, in hopes of forcing an early general election. During the campaign, Mr. Noda signaled a greater willingness to compromise with the opposition than did the other candidates, or Mr. Kan.” “Mr. Noda’s biggest battle will be overcoming the vested interests that have made it so hard to bring change in Japan,” Norihiko Narita, a political scientist and president of Surugadai University outside Tokyo, told the New York Times. “It will be extremely difficult for him to fare any better than those who came before him, to say the least.”

The precarious standing of the ruling Democratic Party, whose ratings have slumped after two unpopular prime ministers, has made politicians adverse to any move that might anger voters. A particular headache for Mr. Noda is a party heavyweight who has turned rebel: Ichiro Ozawa, a longtime advocate of robust government spending to prop up growth, and a fierce opponent of raising taxes. Mr. Ozawa backed the second-place candidate in the party ballot, and to appease him Mr. Noda is expected to tone down the fiscal hawkishness. Cabinet posts were given to two of Mr. Ozawa’s allies.

Yoshihiko Noda and the Tsunami Recovery

Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “Noda will take over the daunting tasks of leading Japan’s recovery from the deadly earthquake and the cleanup of radiation from the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, while also overcoming the challenges of two decades of economic stagnation, an aging population and the rise of neighboring China.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 29, 2011]

“Kan failed to galvanize Japan after the disaster in March or point a new direction for this seemingly rudderless nation. It remained unclear whether the relatively inexperienced Mr. Noda, who has held only one cabinet-level position but is seen as quietly competent, will fare any better in ending Japan’s drift.” “Can we do what is best for Japan, protect the livelihood of the Japanese people, revive the Japanese economy?” Mr. Noda, asked in a speech. “This is what we are being called on to do.”

Noda had to immediately compile a third supplemental budget to pay for the country’s recovery from the March disasters. The Kan government said that reconstruction will cost the government at least $169 billion over the next five years As a fiscal conservative,Noda is one of few within his party to suggest that raising taxes might be necessary to rein in Japan’s deficit. Others in his party argue that such a move is dangerous at a time of economic weakness.

Noda began his term with a visit to a typhoon stricken area east of Osaka. He wore a workman-like uniform and pledged the government would send money to the area to help with that disaster. A couple days before that he visited the stricken Fukushima nuclear power plant and wore protective gear there and praised workers who were trying to bring the crisis under control.

Yoshihiko Noda and Nuclear Power

at Fukushima Noda has said that he will stick to Mr. Kan’s promise to gradually phase out nuclear power, but that it remains necessary in the short term to prevent electricity shortages that could further cripple the economy. He promised to keep Japan on its path of phasing out nuclear power, saying it was “unrealistic” to build any new reactors in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear crisis or to extend those at the end of their life spans. [Source: Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, September 2, 2011]

In his inaugural address Noda stressed that reducing Japan’s dependence on nuclear power would be a gradual process, and that reactors that have fallen idle over safety fears since the Fukushima Daiichi accident would be restarted, albeit after stringent checks and gaining the understanding of local communities. “To build new reactors is unrealistic, and we will decommission reactors at the end of their life spans,” he said. “But it is also impossible to immediately reduce our dependence to zero,” he added.

“Speeding up the recovery and reconstruction process is our biggest mission. We must also work to bring the nuclear crisis to an end as swiftly as possible,” Mr. Noda said. “But our finances are also on the brink. We must strike a balance between economic growth and fiscal discipline.”

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Noda is slowly changing the government's stance on nuclear power generation, which his predecessor, Naoto Kan, wanted to replace with other energy sources. In July, when he was prime minister, Kan revised the long-held Japanese policy of promoting nuclear power and exports of nuclear technology because of the crisis at Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.Noda seems to be taking a more moderate approach by insisting that a stable electric power supply utilizing nuclear power plants is essential for economic growth. In his opinion, both economic growth and fiscal health are inseparable for rebuilding the economy. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 25, 2011]