JAPAN UNDER NAOTO KAN

Kan talking to a

Japanese astronaut In June 2010, after Hatoyama resigned Naoto Kan was named the president of the DPJ and became the prime minister of Japan and the fifth Japanese leader in four years. In his first press conference Kan said, “the main role of politics is to create a society with the “least unhappiness...We will build a strong economy, strong government finances and strong social security systems at the same time.” When took office Kan inherited a bunch of problems: economic malaise, corruption scandals, poor relations with the United States.

Kan had been a major political figure and opposition leader for some time. Described by the New York Times as a plain-spoken politician with activist roots, he is handsome and well spoken, and became involved in politics as a student activist and environmentalist. Nathan Gardels of Global Viewpoint wrote, “More than anyone else in Japanese politics, Kan has lead the democratic revolt of the urban consumer and citizen against the bureaucracy allied with old rural politics of the Liberal Democratic Party that ruled Japan for decades.” In the end though his policies were on the right but he lacked the leadership, political and social skills to effectivelt to sell them to the public and even many members of his own party.

Kan was 63 when he took office. Known for his quick temper, he gained national attention in the mid-1990s when, as health minister, when he exposed his own ministry’s use of blood tainted with H.I.V. He was the Deputy Prime Minister at the time of Hatoyama’s resignation. Kan became the DPJ president by defeating his only opponent Shinji Tarutiko, chairman of the lower house Environment Committee, 291-129 in the DPJ election, in which DPJ member in the upper and lower houses voted. Kan was supported mainly by groups within the party that wanted to distance themselves from Ozawa.

“Mr. Kan is the outsider-turned-prime minister who should have provided leadership,” said Takayoshi Igarashi, a professor of urban policy and a longtime friend of Mr. Kan who serves as an adviser to his cabinet. “The paralysis in Japan just keeps getting worse because leaders cannot answer the people’s expectations.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 26, 2011]

Mr. Kan was supposed to be different. In a nation where so many national politicians are second-, third- and even fourth-generation lawmakers, he was the rare self-made man. He entered public affairs four decades ago as an aide to a prominent feminist leader and rose to national attention when as health minister in the 1990s, he exposed his ministry’s cover-up of a scandal involving H.I.V.-tainted blood products.

When he became prime minister in June 2010, T-shirts appeared with the slogan “Yes, We Kan” — anticipating that he would break the mold of the ineffectual Japanese political leader and shake up the sclerotic status quo. But after only one month in office Kan’s disapproval ratings surpassed his approval ratings. Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: When the March 2011 earthquake struck, "the Diet was discussing whether Kan had taken illegal campaign donations...Japanese politics had become so fractious and unstable in recent times that when the German newspaper Die Zeit produced an illustration of Kan it mistakenly featured a Prime Minister who was booted from office two years earlier.

See Separate Articles of the March 2010 Earthquake and Tsunami and the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis: MARCH 2011 EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI factsanddetails.com; FUKUSHIMA DISASTER factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE GOVERNMENT'S HANDLING OF THE TSUNAMI AND THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com; EARLY HOURS OF THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR DISASTER factsanddetails.com ; VENTING AND BLEEDING AND POURING WATER ON THE FUKUSHIMA NUCLEAR POWER PLANT factsanddetails.com DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF JAPAN (DPJ) WINS BIG IN 2009 ELECTION IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Japan's Dysfunctional Democracy: The Liberal Democratic Party and Structural Corruption” by Roger W. Bowen (2002) Amazon.com; “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II” by John Dowser of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1999. Amazon.com; “Japan Rearmed: The Politics of Military Power” by Sheila A. Smith (2019) Amazon.com; “Japan in Transformation, 1945–2020 by Jeff Kingston Amazon.com

Naoto Kan’s Life

Kan was born in Yamaguchi Prefecture in southern Honshu. He participated in student protests while a student at Tokyo Institute of Technology’s School of Science and worked for civic movements after his graduation. In 1974 he supported Fusae Ishikawa, a women’s rights activist, in her bid for an upper house seat.

Kan was born in Yamaguchi Prefecture in southern Honshu. He participated in student protests while a student at Tokyo Institute of Technology’s School of Science and worked for civic movements after his graduation. In 1974 he supported Fusae Ishikawa, a women’s rights activist, in her bid for an upper house seat.

Kan is known in Japan for his diligence and sharp tongue. He first attracted national attention for his involvement in civic issues and the brusk speaking manner he used in the Diet, which earned him the nickname: Ira-Kan (“hot-tempered Kan”). In the international community he was seen as a reformer and dubbed “Japan’s Tony Blair.”

Kan’s hobbies are shogi (Japanese chess) and mah-jongg. When he was a university students his love of mah-jongg led him to invent a machine that automatically calculated game scores. He obtained a patent for the devise.

Kan married to Nobuko Kan, his cousin and childhood friend, in 1970. Friends told the Yomiuri Shimbun she describes the couple’s relationship as “akin to friends or partisans.” She has said she “hates to lose” and is a steadfast supporter of her husband but has also said she is not adverse to disagreeing with her husband , saying “I’m an eligible voter. If you can’t convince me, you can’t convince the public.” Nobuku is from Okayama Prefecture. Because she is gifted speaker and is said to have a sharp, quick mind, many have suggested that she run for office herself.

According to a survey of the wealth of Japan’s lawmakers Kan’s family assets are the lowest ever for a Japanese prime minister. His declared family assets in 2010 were about ¥22.4 million (about $250,000). His assets including two condominium units in Tokyo and land parcels in Okayama he took over from his father. Kan’s cabinet also had relatively low net worth.

Naoto Kan’s Political Career

In 1980 Kan was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the now defunct Socialist Democratic Federation. During his career he promoted the “third way” that emphasized globalization and reform of the bureaucratic state. He said in the 1990s, “What Japan needs is a party of the consumer and taxpayers not one whose power rests in on the rural constituencies and big construction companies and then is subordinate to the bureaucracy. It is the politicians that are elected who should govern, not the bureaucrats.”

Kan holds a seat from a Tokyo district. He rose to prominence as Health and Welfare Minister in an LDP-lead coalition under Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto in 1996 when he announced that he not the bureaucrats would run the show. He then revealed a scandal involving drug companies and the spread of AIDS through untreated blood and efforts by the Health and Welfare Minister to cover it up. Polls sometimes list as Japan's top choice to be prime minister.

Kan helped formed Minshuto (the DPJ) in April 1998 when he merged four political parties:1) the previous DPJ, 2) the Good Governance Party (Minseito), 3) the Fraternity Party (Shinto-Yuai) and 4) the Democratic Reform Party (Minshu-Kaikaku Rengo). Kan served as the DPJ’s first president in 1998. In September 2003, the Liberal Party (Jiyuto),headed by Ichiro Ozawa, joined the DPJ.

In 2004, as leader of Minshuto, Kan used a pension fund scandal — in which it was revealed that politicians didn’t pay all that he should have to the pension fund — to gain political capital until it was revealed that he too didn’t pay all that he should have and he was forced to resign as leader of his party.

Kan initially served as state minister in charge of national policy in the Hatoyama administration, serving as a point man in the party’s push to rein in the secretive central ministries that have run Japan since World War II.. He later became finance minister before being appointed to Deputy Prime Minister.

Naoto Kan Becomes Prime Minister

Kan effectively become prime minister after winning the DPJ vote for party leader. He defeated Shinji Tarutoko, a relatively unknown legislator backed by Ichiro Ozawa. Kan won with 291 votes to Mr. Tarutoko’s 129. Kan became prime minister when he was approved in a vote in parliament. His party had commanding majority in the more powerful lower house which assured him of winning. He then went through the formality of being appointed prime minister by Emperor Akihito.

disaster prevention drill

“Before the party vote,” the New York Times reported, “Kan vowed to refocus the party on its original goal of ending Japan’s two-decade stagnation. He said he would do this by tackling two of Japan’s most daunting problems, its anemic growth rates and ballooning public debt. “I will carry on the torch of reviving Japan that the Democratic Party received from the people,” he said. Touching on his predecessor’s difficulties, he said he would honor an agreement to relocate a United States Marine air base on Okinawa and work to rebuild trust between the allies. But he also said he would place equal emphasis on improving ties with China, with whom Japan now has larger trade relations.”

After winning his party’s vote the New York Times said: “Mr. Kan faces an uphill task in trying to win back the public support that Mr. Hatoyama had squandered in months of indecision over the fate of an American military base. He must also help the party regain the momentum it had in August after winning a landslide election victory that ended a half-century of virtual one-party rule...Mr. Kan promised to move the party away from the sort of money politics that the scandal-tainted Mr. Ozawa had come to represent.”

Kan accession to the position of prime minister was seen as a centralization of power into the prime minister’s position and an end to the power-sharing relationship between Kan, Hatoyama and Ozawa, which in turn reduced Ozawa’s role as the “shadow prime minister.” The LDP criticized Kan for being nothing more than another page from the same book as Hatoyama. Kan himself distanced himself from he DPJ manifesto, saying it generous handouts for child allowance and farmer subsidies did not make sense at time when Japan needed to tighten its belt and make some changes to get its economic house in order.

Naoto Kan as Prime Minister

Kan started off his term as prime minister with a relatively high approval rating of 64 percent. Many attribute the initial high ratings of Kan’s cabinet to his shutting out Ozawa and his supporters from key positions in the government. When Kan became prime minister he told Ozawa to “be quiet for a while.” When he defeated Ozawa for the party leadership he was able to shut Ozawa out of the government.

receiving some plums

Kan made the economy a No. 1 priority and put off making any decisions about the Futenma air base in Okinawa, which had chilled relations with the United States, and dealt with aggressive actions by China, such as its hardball tactics following the collision of a Chinese trawler with Japanese Coast Guard vessels around islands claimed by Japan and China.

Kan also lacked political skill. One of his biggest mistakes was pushing for a consumption tax on the eve of upper house elections. He initially came out strong, pushing the tax as bitter medicine that Japan needed to take if is was going to do something about it national debt but later when criticism of tax mounted he waffled and seemed mealy-mouthed. In debates Kan often came across as evasive and wishy-washy instead of standing up for what he believed even if it was unpopular. He sometimes backed off from original statements, leaving him open to attacks from all sides. His exchanges in lower house debates were often testy and ill-tempered.

The New York Times reported: “Japan's recession-weary voters embraced Mr. Kan's tough talk, giving the Democrats a larger-than-expected bounce in the polls. But Mr. Kan saw his approval ratings quickly drop, first after he proposed a tax increase before an election — a political no-no in almost any country — then compounded the trouble by seeming to vacillate when the proposal proved predictably unpopular among voters. The apparent flip-flopping appeared to raise broader doubts in the country about whether the inexperienced Democrats, an alliance of L.D.P. defectors and former socialists who once seemed permanently relegated to Japan’s opposition sidelines, could mold themselves into an effective governing party. Mr. Hatoyama’s and then Mr. Kan’s inconsistencies appeared to fan fears of what some political experts characterized as a leadership crisis in Japan, where voters are eager to find someone to point a way out of the country’s seemingly intractable decline.”

Upper House Elections in July 2010

In July 2010, the DPJ lost its majority in the upper house. It won 44 seats giving its coalition a total of 110 seat (106 of those DPJ seats), below the 122 seats needed to form a majority and down 13 seats from before. The LDP won 51 seats giving its opposition coalition a total of 132 seat (84 of those LDP seats), up from 14 before. Voter turn out was 57.9 percent.

Among the small parties, most of them LDP allies, Your Party (a new party made up of former LDP members) won 10 seats, giving it 11 seats total; Komeito (the LDP’s coalition partner) won nine seats, giving it 19 seats total; the Japan Communist Party won three seats, giving it six seats; the Social democrats (former DPJ coalition partners) won two seats, giving it four seats total.

Celebrities didn’t fare very well, with actors, singers and former baseball players all losing, regardless of which part they ran for..Among those won, was two-time Olympic judo gold medalist Ryoko Tani, who won a seat for the DPJ.

Fall Out of the Upper House Election

The election was widely viewed as an embarrassing and stinging defeat for the DPJ, which had only been in power for 10 months, and its policies. The DPJ’s poor performance was partly blamed pm Kan’s remarks about a possible consumption tax. Although many Japanese say they supported the tax as a means of reducing Japan’s debt, the way Kan handled the issue was roundly criticized.

The New York Times said the election showed “growing voter disappointment with the party’s apparent inability to deliver on promises to revamp the country’s sclerotic postwar order.” The Financial Time said “Voters gave Kan a yellow card — and the election could lead to a “sustained period of political instability.”

The LDP did well in rural areas while labor unions were still vital in bring in votes for the DPJ. Ozawa’s tactic of fielding two candidates in multi-seat constituencies seemed to have failed miserably as with all but one failing to win a set. Current and former DPJ allies lost seats and influence.

Kan apologized for the DPJ’s dismal showing but said he was determined to stay on as prime minister. His camp and that of Ozawa blamed each other for the loss, with Ozawa’s people blaming Kan for breaking pledges for previous elections and Kan’s people blaming Ozawa for tarnishing the DPJ with is scandals.

Kan Versus Ozawa in the DPJ Election

in Okinawa

In September 2010, the DPJ held an election to chose its president, which meant that since the party was in power the election was a defacto election for Japan’s leader. Kan had the support of key members within the DPJ. A group led by Ozawa hoped to put their weight behind a candidate opposing Kan with Ozawa finally deciding to run himself despite having a cloud of scandal hanging over him. Ozawa ran on a platform of giving more power to local governments and fulfilling promises made in the 2009 election and spending a lot of money to achieve that.

It was not totally clear why Ozawa decided to run. Some speculate he did it because he had been disrespected by Kan. Some cynics even said he did it avoid being indicted. According to Japanese law sitting prime ministers can not be prosecuted for a crime. One of the most bizarre episodes of the DPJ election campaign was when Hatoyama came out in support of Kan one day and the next day changed his mind, supporting Ozawa as “a way of returning the favor for making me prime minister.” A couple days before he announced he going to run Ozawa called Americans “simple minded” and “somewhat like single-celled organisms.”

In September 2010, Kan was re-elected as DPJ President — allowing him to keep his post as Prime Minister — in the DPJ election against Ozawa with Kan taking 721 points to Ozawa’s 491. Kan edged out Ozawa in the vote among law makers, getting the votes of 206 lawmakers compared to Ozawa’s 200, and swept the voting among party members and voters taking 251 out of a possible 300 points, winning in almost every constituency.

In the voting 1,222 points were up for grabs. Each vote by the DPJ’s 411 Diet Members was worth two points, accounting for about 70 percent of the vote. About 2,400 DPJ local assembly members were allotted 100 points while 340,000 non-lawmaker DPJ members and supporters accounted for 300 points. The vote was the first DPJ election since 2002 in which rank-and-file DPJ members and supporters cast ballots.

Among lawmakers Kan was supported by his own group and that key members of his cabinet as well as from first-term lawmakers. Kan was helped further that the DPJ government would lose credibility abroad and support in Japan if Japan were to have its third prime minister in year, Ozawa was supported by his group, the largest in the party, and most of the group led by former Prime Minister Hatoyama.

Kan After the DPJ Election

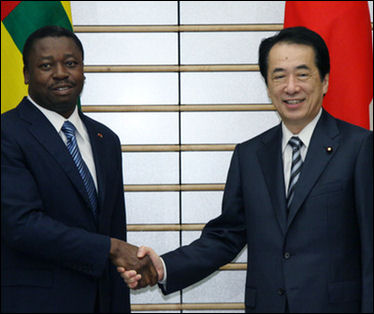

with the leader of Togo

Winning the DPJ election gave Kan a boost. There was the perception that he had won something, and this took the sting out of the disappointing showing by his party in the upper house elections three months earlier. Among the first things that Kan did was name foreign minister Katsuya Okada as secretary general of the DPJ, the position formally held by Ozawa, who endured more question about his political funds after the DPJ election.

Kan’s approval rating a week or so after the DPJ election was 66 percent, much higher than the 40 percent it dropped to before the election. Analysts said the high rating probably had more to do with the relief that Ozawa was finally out of the picture rather than being particularly pleased with Kan.

A few days after the election, the Kan government and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) bought up large amounts of dollars with yen in global currency markets in an effort to lower the value of the yen and bring back some vigor to Japan’s export-led economy. Later the BOJ lowered their interest rate to 0. Neither moved helped to stimulate the economy much or lower the value of the yen. The moves seem to have been made with the government putting some pressure on the BOJ, raising quests about the BOJ’s independence.

After the election Kan pushed for a reduction in the corporate tax — which stands at 40 percent, the highest in the developed world — to help Japanese companies become more globally competitive.

The DPJ held talks with New Komeito, a coalition partner of the LDP, to work together in policies and possibly form a “partial coalition.” New Komeito decided to offer some support to the Kan government in return for support for its effort to distribute ¥1.2 trillion to local government to revitalize rural areas.

The third round of budget screenings began in October 2010,. This time the target was to identify waste in budget requests by the three top officials at each ministry. These hearings set off clashes within the DPJ as the budgets that were attacked had been drwwn up by officials within the DPJ government. During the screenings the government decided to terminate some special accounts.

Economic Policy Under Kan

The Naoto Kan government that came into power in June 2010 said it was it was going make the economy a No. 1 priority, focus on cutting public debts, and boost domestic demand and attract foreign investors. Kan He said it was time for Japan to act “before it becomes like Greece.” he promoted his “third way” which emphasized a need to fund promising fields such as nursing care, medical services and the environment and tourism, as opposed to the “first way” which emphasized infrastructure projects such as road as dams and the “second way” Koizumi structural reforms.

In December 2010, Prime Minister Naoto Kan proposed major tax reforms for fiscal 2011 that included: 1) cutting the corporate income tax from 40 percent to 35 percent; 2) introducing an environmental tax in October 2011; 3) lowering the corporate tax rate for small businesses from 18 percent to 15 percent; 4) limiting deductions from taxable incomes of salaried workers with relatively high incomes and corporate executives.

The Kan government also: 1) issued orders to accelerate the study of whether or not to impose a consumption tax was needed; 2) advised that child allowances be raised to ¥ 20,000 per month from ¥13,000 for children under three years old; 3) called for studies of ways to improve farm productivity and competitiveness in global markets; and 4) asked that regional government be given more discretion on how they use state funds.

The Economist reported in February 2010: Kan’s efforts to reduce taxes and attract foreign investment — marks a remarkable maturation for the DPJ, which strode into office 16 months ago clutching a sheaf of anti-business policies such as reversing the privatization of the post office...creating a three-year debt moratorium for small firms and introducing unwieldy targets for carbon-emission reduction.”

Foreign Policy Under Kan

For the most part Kan didn’t come off very well on the international scene. The Chinese bullied him; the Russians mocked him; and the Americans ignored him. On one occasion when he was with Chinese President Hu Jintao he looked befuddled and spoke from notes in his hands. One widely circulated photo showed Hu refusing to shake hands with him. At a G-20 meeting in Seoul only the representatives of the European Union and Turkey met with him for bilateral talks.

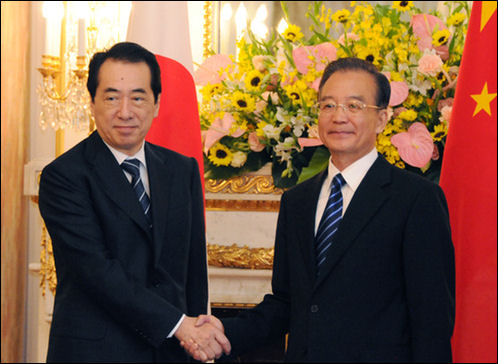

with China's Wen Jiabao

When he became prime minister, Kan admitted he had little experience in foreign affairs. At major international meeting such as the G-8 summits Kan came across as being a little sorts because he couldn’t speak English very well. Before his first G-8 meeting Kan sought the advice of Columbia University Prof. Gerald Curtis and former Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone and took his foreign minister Katsuya Okada with him to the meeting.

Seiji Maehara, who was Foreign Minister for a while, was one of the architects of its Kan’s foreign policy, in which the government took a tougher stance toward China than it did under Hatoyama. Maehara also called for keeping Japan close to the United States while building up its own military capabilities.

Island Dispute with China See International

Low Approval Ratings for Kan, Gridlock and Fired Ministers

Kan’s ratings took a dive”dropping from 66 percent to 53 percent and his unapproval rating increased from 25 percent to 37 percent over a couple of weeks” after the stand-off between Japan and China over Senroku Island’s that started with a collision of a Chinese fishing vessel and Japanese coast guard ship in September 2011. In an effort to improve his image Kan launched the Kan-Full Blog,

Kan reshuffled his cabinet in September 2010. In November 2009, Justice Minister Minoru Yaagida was forced to resign after only two months on the job after he jokingly saying that his job was “easy” before a gathering of supporters. “Being justice minister is easy because I only have to remember two phrases,” he said. “I can use either one if I am stuck for an answer. The two phrases he said were: “I can’t comment on a specific issue” and “We are dealing with the matter based on the law and available evidence.” His critics said the comments demeaned his job and the legislative process.

In December 2010, Kan’s approval rating dropped to 25 percent. At that time Kan said he would stay in power even if his approval rating “drops to 1 percent.” In January 2011 he reshuffled his cabinet, to largely collective yawn. The reshuffling took place after Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshito Sengoku was forced to resign because of his overly aggressive and combative style made an already difficult situation with the opposition worse. Sengoku was replaced by Yukio Edano. Kan named Seiji Maehara as foreign minster, Yoshihiko Noda as finance minister and Yoshihiro Katayama as internal affairs minister. Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano was the public face for the Kan government during crisis following the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011.

After the reshuffling some people complained that Kan’s cabinet was filled with cronies and was not a cross-section of the party. Okada was moved from foreign minster to head the DPJ. Noticeably absent were members of the Ozawa group. The two female members of the cabinet were Renho, a former television personality serving as State Minister in Charge of Government Revitalization, and Yoshito Sengoku, National Public Safety Commissioner and state minister in Charge of Consumer Affairs and Declining Birthrate.

Kan faced an uphill battle in Parliament to pass a series of bills related to the 2011-2012 budget before the new fiscal year in April 2011. Perhaps the most crucial of these bills was one authorizing new government bonds to finance the Japanese government’s huge deficits. With opposition parties in control of the upper house of Parliament, Kan would seem to have few prospects for breaking the political gridlock. The largest opposition party, the Liberal Democrats, vowed to block bills to force an early election. One reason for the Democrats’ dwindling public support has been a series of political funding scandals involving Hatoyama and Ozawa. [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, March 6, 2011]

with leaders from China and South Korea

Kan Admits Receiving Illegal Donations Unknowingly

In March 2011, the day before Japan was struck by disastrous earthquake and tsunami, Kan said he would not resign after acknowledging that his campaign office had unknowingly received illegal donations from a foreign supporter, days after his foreign minister stepped down for a similar reason. Kan told a parliamentary committee that he did not know the donor was a foreign national. Political finance laws permit lawmakers to accept donations only from Japanese nationals. “This person has a Japanese name, and I thought he was a Japanese citizen,” Mr. Kan said. In Japan, many Koreans who have lived in Japan their entire lives and offspring of Korean parents who have lived in Japan their entire lives are still regarded s Korean citizens and foreign nationals in Japan. [Source: AP, New York Times, March 11, 2011

About a week before that Japan’s foreign minister, Seiji Maehara resigned over illegal campaign donations. Maehara said he had received 250,000 yen, or about $3,000, in donations since 2005 from a South Korean permanent resident in Japan, who said she was an old neighborhood friend and was “unaware” that the law barred her from giving a gift.

Maehara, 48, a handsome and hawkish member of the DPJ, was widely been seen as being next in line to replace Kan as prime minister. The New York Times reported that his resignation over such a seemingly minor infraction was a measure of the increasingly weak position of Kan. Maehara was replaced by Takeaki Matsumoto as foreign minister.

Around the same the time government minister in charge of welfare and pensions — Ritsuo Hosokawa — confessed he was ignorant about a key directive his ministry issued on pension premium wavers for full-time housewives and Kan rammed the 2011 budget bill through the DPJ-dominated lower house in such a way that a vote was not necessary in the opposition-backed upper house, angering opposition parties.

Kan and the Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster See Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011

with Japan's national women's soccer team

Elections in 2011

In February 2011, the DPJ did poorly in elections in Nagoya and Aichi Prefecture, thought to be DPJ strongholds. DPJ-supported candidates lost both Aichi governor election and the Nagoya mayor race. The DPJ also lost a key election in Hokkaido in October 2010.

The DPJ did poorly in elections for governors and prefectural assemblies in mid April 2011, a month after the March earthquake and tsunami. DPJ and DPJ-supported candidates were defeated by LDP and LDP-supported candidates in gubernatorial races in Tokyo, Hokkaido and Mie Prefecture and emerged as dominant in 40 of the 41 prefectural assembly elections. Incumbents won eight of the 12 gubernatorial races.

LDP leaders said the election was a reflection of dissatisfaction by voters over the way the Kan government handled the earthquake and tsunami crisis. Campaigning was low key in the wake of the disaster and, understandably, disaster prevention and nuclear energy were important issues. Many elections in disaster-hit areas in Fukushima, Miyagi and Iwate prefectures were postponed if for no other reason than that the polling stations had been destroyed.

Kan’s Failure to Lead

surveying tsunami damage Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times,”Kan followed an all-too-familiar pattern, starting out with approval ratings above 60 percent but squandering it amid rising criticism that he was failing to show leadership. [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, August 26, 2011]

“This is a nation groping in the dark for what its new goals should be,” said Koichiro Kokubun, a philosophy professor at Takasaki City University of Economics. “Prime Minister Kan’s biggest failure was not pointing a direction.”

Of course, Mr. Kan faced a host of deep and formidable problems in office that would have challenged any leader, even without the earthquake and the tsunami, which left 20,000 dead or missing, and the resulting nuclear accident. Those difficulties, a moribund economy, an aging population and paralyzing divisions within both the governing Democratic Party and Parliament, will also hinder his successor.

But political analysts and even Mr. Kan’s allies say that Mr. Kan’s failure has also been at least partly his own doing. In recent months, Mr. Kan has faced constant criticism for what many here see as his impulsive handling of the nuclear crisis in Fukushima. At the same time, his lone-wolf style and refusal to engage in Japan’s requisite consensus-building have alienated almost every major player in the political establishment: bureaucracy, the news media, even members of his own party.

Kan’s Fecklessness as a Communicator

addressing the nation on the tsunami Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “Even his supporters say his biggest liability was an inability to communicate with the public. Like many of his predecessors, he was often compared unfavorably with a previous iconoclastic leader, Junichiro Koizumi, who proved much more successful as prime minister in his five-year term, which ended in 2006.

While Mr. Koizumi had mastered the art of short news conferences, tossing out pithy sound bites that resonated with voters, Mr. Kan refused to give such impromptu briefings. Mr. Koizumi built a populist appeal that he used to defeat a powerful interest group, the post office, which had become a crucial cog in the old-style political machines that Mr. Koizumi was trying to dismantle.

“He could have gotten out in front of this issue, but he didn’t communicate,” said Gerald Curtis, a professor of Japanese politics at Columbia University.

Mr. Kan’s adviser, Mr. Igarashi, said: “Prime Minister Kan never seemed to grasp the importance of communication. I told him and told him, but he had this belief that a man should be judged by actions, not words.”

Kan After the Tsunami

in the tsunami zone Martin Fackler wrote in the New York Times, “Three months ago, Japan’s unpopular prime minister, Naoto Kan, seemed to have a chance at a comeback, winning applause from Japan’s now nuclear-phobic public by facing down the powerful atomic energy establishment and ordering the shutdown of a nuclear plant in a risky earthquake fault zone.”

“But Mr. Kan proved incapable of seizing the moment. His approval ratings quickly resumed their slide, falling into the mid-teens, even as polls showed opposition to nuclear power growing after the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in March.

Indeed, one of the biggest complaints about Mr. Kan has been his inability to point a way toward recovery. In a sign of the indecision that seems to have paralyzed his administration, the government announced Friday that it would halve radiation levels in areas contaminated by the stricken Fukushima Daiichi plant within two years. It failed to explain how it would do so.

Mr. Kan got off to a strong start in May by ordering the shutdown of the vulnerable Hamaoka nuclear power plant. He also won popular applause by criticizing the cozy ties between the nuclear industry and regulators, who are widely blamed for allowing the Fukushima plant to operate without adequate protection from tsunamis. But Kan failed to persuade the public that his antinuclear stance represented a serious change of heart by a leader who before March supported building new nuclear plants. Worse, analysts say, he failed to lay out a detailed road map of how Japan might realistically rid itself of nuclear power without all the lights going out.

Pressure on Kan to Resign After the Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster

at Fukushima The was some discussion of the DPJ and LPD forming a “grand coalition” to deal with the fall out from earthquake and tsunami. The LDP said it would help with disaster relief but not as part of a government with Kan’s party. An April 2011 a Yomiuri Shimbun survey found that 64 percent of the people asked supported a grand coalition.

About two months after the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami it seemed as if Kan’s grace period was over and attacks on his leadership resumed and taken to a nigher level with a slew of accusations that he poorly handled the earthquake and tsunami fallout and Fukushima nuclear crisis. A poll taken in early June, 54 percent of those who responded said that Kan should resign and 36 percent said he should stay. At that point Kan’s approval rating was 31 percent and his disapproval rating was 59 percent. A Yomiuri Shimbun survey in July found that 72 percent of those interviewed wanted Kan to resign by the end of August.

In early June Kan announced his intention to resign once certain progress is made in rebuilding hard-hit areas and containing the nuclear crisis triggered by the natural disasters. He did not state when he would will step down but said the passage of three key bills were conditions for him to keep his promise to leave office. The three bills Kan referred to are the second supplementary budget for fiscal 2011, special legislation to require utility firms to buy renewable energy, and a special bill to issue debt-covering government bonds.

Kan Survives No-Confidence Vote

On June 2, 2011, Justin McCurry wrote in The Guardian, “Kan comfortably survived a no-confidence motion after offering to resign as soon as plans for Japan's recovery from the tsunami and nuclear crisis are in place. Legislators in in the 480-seat lower house of Japan's parliament voted down the motion by 293 votes to 152. By offering to quit, possibly in the autumn, Kan has bought himself a few more months in office. The move will enable him to oversee the operation to stabilise the nuclear plant — which is expected to take several months — and to secure emergency funding for the reconstruction of the country's battered north-east coast.” [Source: Justin McCurry, The Guardian, June 2, 2011]

“The fate of the motion, submitted by the main opposition Liberal Democratic party (LDP) and other opposition parties, was sealed after Kan's main rival in his own Democratic party of Japan (DPJ), Ichiro Ozawa, indicated he would abstain along with 50 of his supporters, having earlier threatened to side with the opposition. The no-confidence motion has exposed divisions inside his own party, with DPJ executives vowing to take action against rebel MPs who voted with the opposition. Kan, who has been in office for almost a year, managed to pre-empt his opponents earlier in the day when he pledged to resign once his disaster mission was complete, and suggested it was time the political elite made way for a new generation.”

“At one stage it had looked possible that opposition parties would come tantalisingly close to securing the votes of the 80 or so governing party MPs they needed to force Kan to resign or call a general election. Kan remained vague about when he would step down. Shizuka Kamei, the leader of a minor partner, said he should resign as soon as the nuclear crisis has been resolved.”

"Among possible scenarios the best one would be Kan voluntarily resigning and the DPJ forming a coalition with the LDP to stabilise politics," Yasuo Yamamoto, senior economist at the Mizuho research institute in Tokyo, told The Guardian. "Unstable politics would weigh on stock prices and delay reconstruction after the disaster. From both Japanese and foreign investors' point of view, now is not the time for political turmoil. Japan has various issues it needs to address swiftly — not only reconstruction but also tax and social security reform, TPP [a transpacific free trade agreement] and energy policy, which requires political initiative."

The return to business as usual in Nagatacho, Tokyo's political nerve centre, has been met with anger and disbelief in the country's north-east, where about 100,000 people are still living in evacuation shelters and construction of temporary housing is behind schedule. An 82-year-old resident of Kamaishi who was living in a local school told the Asahi Shimbun: "Once things become more settled in the region struck by the disaster, they can go ahead and dissolve the lower house as many times as they like. If they dissolve it now, I will abstain from voting."

Kan's cabinet resigns

Kan Finally Steps Down

Kan officially stepped down in late August 2011. In mid August his approval rating dropped to an all time low of 18 percent, with 72 percent of those surveyed in the Yomiuri Shimbun survey they disapproved of Kan. His final action in office was confirming that he was finally stepping down. The New York Times reported, “Indeed, this has been one of the most protracted resignations in recent memory; Mr. Kan first promised to resign in June, but then tried to prolong his time in office by vowing to pass disaster-related bills first.

Bruce Klinger wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “In June, Kan beat back a no-confidence vote by the national legislature for him to resign — by agreeing to resign. That hollow victory, the legislative equivalent of offering to quit before being fired, bought him some time. But during his subsequent tenure as dead man walking, Kan frittered away the opportunity to be the bold leader his nation yearned for...Kan's wife said she didn't pack more than summer clothes when her husband was selected as prime minister in June 2010, since she didn't know how long he would actually remain in office.”

About five weeks after Naoto Kan stepped down as prime minister, he donned the clothes of a pilgrim and resumed his pilgrimage that he had been undertaking to Shikoku’s 88 main temples, which he began back in 2004 with a shaven head. Christal Whelan wrote in Daily Yomiuri, This marked his sixth journey in a pilgrimage done in sections over an eight-year period along the 1,400-kilometer route. His lone figure--a pilgrim's staff in hand and wearing a conical sedge hat, white trousers and jacket--presented an archetypal image of the pilgrim on a quest for healing and rejuvenation through exposure to objects and places held sacred. Pilgrimages--journeys to holy places traditionally made on foot--are thriving worldwide.” [Source: Christal Whelan, Daily Yomiuri, November 6, 2011]

Image Sources: Kantei, Office of Japanese Prime Minister

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, Daily Yomiuri, Japan Times, Mainichi Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012