EMPEROR HIROHITO

Emperor Hirohito was Japan's longest reigning (63 years) and longest-living (87 years) emperor. One of the most important figures of the 20th century, he was the Emperor of Japan when it became a world class military power, when it invaded China, when it raped Nanking, when it attacked Pearl Harbor and when it rose to become the world's second economic superpower. During World War II millions of Japanese young men died in his name. The extent of Hirohito’s involvement in the war is still not known. It is not clear whether he was active in shaping policy or whether decisions were simply, made in this name.

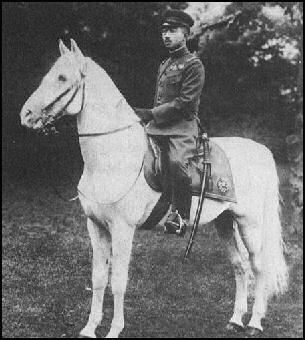

Emperor Hirohito went through an amazing transformation after World War II that mirrored the changes experienced by his country. Before the war he was "a-god-king-generalissimo," who appeared in public on a white stallion before people who were forbidden from photographing and even laying eyes on him. After the war he was democratic monarch who waved to crowds dress in a fedora and was regarded by some as a reformer.

The Showa Period (1926-1989) refers to the period of Emperor Hirohito's rule, which extended across the better part of the 20th century. Showa means "Enlightened Peace" — an ironic name for a player in one of the most violent episodes of world history — World War II.

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: MEIJI PERIOD AND BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN CHINA: WAR AND OCCUPATION BEFORE AND DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; OKINAWA, KAMIKAZES, HIROSHIMA AND THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com;SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY: TAISHO PERIOD (1912-1926) THE TOKYO EARTHQUAKE factsanddetails.com; JAPAN BEFORE WORLD WAR II: THE RISE OF JAPANESE MILITARISM AND NATIONALISM factsanddetails.com; JAPAN GEARS UP FOR WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com JAPANESE EMPEROR AND IMPERIAL FAMILY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE EMPEROR’s DUTIES AND LIFESTYLE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ; EMPEROR AKIHITO AND EMPRESS MICHIKO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPAN AFTER WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPAN’s ECONOMIC MIRACLE AND THE 1950s, 60s, AND 70s Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPAN’s BUBBLE ECONOMY AND COLLAPSE Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Hirohito and Japan cidc.library.cornell.edu ; PBS Article pbs.org/wgbh ; ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Hirohito’s World War II Surrender Speech mtholyoke.edu/acad Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Japanese History Documentation Project openhistory.org/jhdp ; Cambridge University Bibliography of Japanese History to 1912 ames.cam.ac.uk ; Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; WWW-VL: History: Japan (semi good but dated source ) vlib.iue.it/history/asia/Japan ; Forums Delphi Forums, Good Discussion Group on Japanese History forums.delphiforums.com/samuraihistory ; Tousando tousando.proboards.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan” by Herbet P. Bix (HarperCollins, 2000) Amazon.com is a critically acclaimed 800-page work that won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction and the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2000. Bix worked on the book for 10 years while he was professor history at Hitosubashi University in Tokyo. Also: “Inventing Japan: 1853-1964" by Ian Buruma (Modern Library, 2003) Amazon.com; “Japan at War in the Pacific: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Empire in Asia: 1868-1945" by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com; “The Making of Modern Japan” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com; “Imperialism in East Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries —With a Focus on the Case of Japan in Korea” by John B. Duncan Amazon.com; “The Meiji Restoration” by W. G. Beasley and Michael R. Auslin Amazon.com; “The Culture of the Quake: The Great Kanto Earthquake and Taisho Japan (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2015) Amazon.com; “Party Rivalry and Political Change in Taisho Japan” (Harvard East Asian Series, 35) by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century” by Peter Duus Amazon.com; “The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics and the Opening of Old Japan” by Christopher Benfey (Random House, 2003) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century” by Marius B. Jansen Amazon.com

Hirohito's Early Life

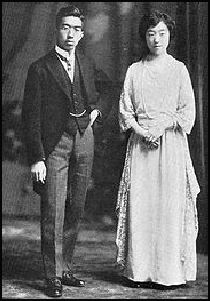

Hirohito and Empress Nagako Emperor Hirohito was born on April 29, 1901 in Tokyo. He was the eldest son of Yoshihito, the Taisho Emperor. At the age of seven he was enrolled at the Peer's School, which was run Maresuke Nogi, an infantry general who distinguished himself in the Russo-Japanese War. Hirohito was taught by Nogi and two Confucian tutors about discipline, loyalty, samurai virtues and responsibilities that went along with being a descendant of the sun goddess.

Hirohito was 11 when the Meiji Emperor died and his father ascended to the throne and became the Taisho Emperor. After that Hirohito was taught by war hero Admiral Heihachiro Togo.

At the age of 20, Hirohito became the first royal prince to leave Japan and see the world. He traveled around Europe and was given a welcome reception. He played golf, went fishing in Scotland, shopped in Paris, visited museums and even challenged the rule that Japanese royals were not to touche money by having his aids place bets for him on British horse races. During the trip, he wrote his brother, "I discovered freedom for the first time in England."

In 1923, shortly after the devastating Tokyo Earthquake, an assassin took a shot at Hirohito as he rode in an imperial limousine — and came close to hitting his target. After that Hirohito’s sequestered existence became even more sequestered.

Hirohito's Family

On January 26, 1924, Hirohito married Empress Nagako, the eldest daughter of Prince Kuni. The marriage was arranged when he was 16 and she was 14 but almost didn't come off because some advisors were concerned about rumors that some of her relatives were color blind. The wedding was delayed for a year because of the Great Tokyo earthquake in 1923.

Empress Nagako was not well liked by the Japanese people. She reportedly didn't get on well with her husband early in the marriage and did little more than fulfill the scripted duties expected of her. Her main job was to produce a make heir but that didn't happen until after four girls were born. During fifth pregnancy, it was widely believed that Hirohito would take another consort if the child wasn't a boy. Cannon fire announced it was a boy. She also gave her daughter-in-law, Empress Michiko, a hard time in part because she was a commoner and she was educated at a Catholic school.

Hirohito's family, including future Emperor Akihito

Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako had eight children: Princess Shigeko (1925-61), Princess Sachiko (1927-28), Princess Kazuko (1929-89), Princess Atsuko (1931-), Emperor Akhito (1933-), Princess Hitachi (1940-), Prince Hitachi (1935-) and Prince Takado (1939).

Hirohito's Character and Interests

Hirohito has been described as a shy, troubled, aloof, lonely, reclusive family man who was puritanical in private and formal in public. The image that most Westerners have of Hirohito is a bespectacled man in a military uniform astride a white horse or a man in a top hat and morning suit submitting himself to Gen. MacArthur.

Hirohito’s biographer Herbet Bix described him as a "nervous man" of average intellect, having "a strong streak of opportunism" and "moral cowardice." His teachers had convinced him that the preservation of the Japanese monarchy was imperative to the survival of Japan itself and Hirohito saw this as his primary responsibility. Explaining what made Hirohito tick, Bix said "he was educated to retrieve the lost powers — the power that his father, the Taisho Emperor, hadn't been able to exercise...War was never central to his character, but he was given a military education and an education in realpolitik."

Every morning Hirohito ate an English breakfast — a fried egg, grilled tomato and bacon or sausage — took English tea in the afternoon and had a golf course built on the palace grounds. He had a strong interest in marine biology. He spent hundreds of hours looking though the eyepiece of a microscope in his specially-made laboratory in the Imperial Palace.

Hirohito as Emperor

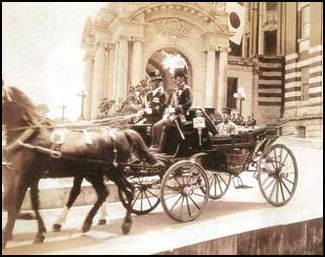

Hirohito on a visit to Taiwan Hirohito ascended to the throne on Christmas Day, 1926 and became the 124th emperor of Japan, succeeding his father, the Taisho Emperor.

Hirohito had the power to appoint and dismiss cabinet members and generals. In 1928, he forced one prime minister to resign for not stopping militarists from conspiring to kill a Chinese warlord in Manchuria. After that with the exception of 1936 and World War II Hirohito said that he chose to stay aloof from politics. In 1936, he ordered the execution of 19 militarists who led an unsuccessful coup d'etat against the civilian government in the Emperor's name.

Hirohito allied himself with hard line factions in the Japanese military. He helped military leaders weaken political parties, brutally suppressed political dissidents, promoted anti-democratic imperial ideology and enhanced his power at the expense of democracy. Bix said, "He wanted to rescue and eventually eliminate the power, the voice of elected officials in making national policy. He favored bureaucrats."

Emperor Hirohito and World War II

The Japanese military committed a number of atrocities in China and Korea and in World War II in the name of the emperor. The conventional wisdom has traditionally been that Emperor Hirohito was a puppet of the military rulers, who ruled Japan from the late 1930s through World War II. He reportedly made no decisions, and was not involved in the running of the government. In 1946, Hirohito said that he "was virtually a prisoner and powerless."

Some historians argue that if Hirohito had stepped in and tried to stop the militarists this would have only resulted in a coup that would have ousted the civilian government as feeble as it was and led to the Emperor's dethrone. Hirohito had been indoctrinated as young man in the belief that preserving the emporership was his most important duty.

Bix said, "Hirohito was not Hitler or Mussolini. But he was a highly activist, interventionist, dynamic emperor, insisting at all times that he had his say in the making of national policy." Bix believed that the notion of Hirohito as a puppet was propaganda was cooked up to serve both Japanese and American interests after the war.

Hirohito criticized the alliance of Japan with Nazi Germany, supported talks with the U.S. over the cut off of oil and called for restraint on eve of Pearl Harbor but also condemned the army for not conquering more territory in China

Even though Hirohito tried to prevent Japan from entering the war he was a strong supporter once it got going. Hirohito was involved in the planning of the Pearl Harbor attack. Mitsuo Fuchida, the pilot who led the Pearl Harbor air attack and transmitted the famous “Tora, tora, tora,” said he showed photographs from the attack to Emperor Hirohito, who he said was fascinated with images and kept saying he wanted to show them to the Empress.

Hirohito also praised the victims in Singapore, the Philippines and the Pacific, received detailed reports about military planning and offered advice on things like the Bataan Death March and the Battle of Leyte. He used the powers invested in emperor to participate "directly and decisively" in policy making.

Many think that Hirohito was not blamed because the Japanese Constitution stipulated that “The Emperor is sacred and inviolable” which meant that he had no legal responsibility for the war and he was restricted in his input in government policy.

Nagasaki, Hirohito and the Decision to Surrender

Japan's Supreme War Council was meeting and debating what to do about the Soviet invasion of Manchuria which had been launched that day when the Nagasaki bomb exploded. Even after the details of the Nagasaki bomb were made clear, half the members of the council insisted that Japan should continue fighting. The debate was deadlocked between the pacifists and militarists. Finally one member of the council, Kiichito Hiranuma, shocked everyone by asking the Emperor Hirohito what he thought they should do. Asking the emperor, who was regarded as a God, to speak was unprecedented if not sacrilegious.

"For the first time in Japanese history," wrote Yale professor James R. Van de Velde in the Washington Post, "the emperor himself rose to break the political stalemate and directed his cabinet to end the war and stop the suffering of his people."

As surprising as the move was, Hirohito seemed prepared to make it. He reportedly had already decided to surrender before the dropping of the Nagasaki bomb and said the terms of the Potsdam Declaration should be accepted, saying “that continuing the war means destruction of the nation and a prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. The time has come when we must bear the unbearable. I swallow my tears and give my sanction to the proposal to accept the Allied proclamation."

Emperor Hirohito Announces the Surrender

The Japanese laid down their arms on August 15, 1945, nine days after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and six days after one was dropped on Nagasaki. At noon on August 15, 1945, in the his first ever public speech, Emperor Hirohito formally announced his country surrender with typical Japanese indirectness during a live radio broadcast from Tokyo’s Nippon Budokan hall. In the speech said that "the war situation had developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of world have all turned against her interests. Moreover, the enemy had begun to deploy a new and cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives."

The Japanese people had never heard their Emperor speak before. When the Emperor addressed the nation, many Japanese held their swords and were ready to take part in a mass suicide known as the Honorable Death of the Hundred Million. The day before a military contingent captured the Imperial Palace in an attempt to prevent the emperor from making the announcement.

Emperor Hirohito Renounces His Divine Status

As part of the surrender agreement, the allies allowed Hirohito keep his throne but required him to renounce his semidivine status. In January 1st, 1946, Hirohito publicly denounced "the notion that the emperor is a living god" and rejected the idea that "the Japanese are a superior to other races destined accordingly to rule the world."

Nobel Prize-winning author One said one of the most momentous events in life was when the Emperor confessed after World War II that he was not a God. He, like other Japanese, had been taught in school that the Emperor was a indeed god and many believed that was the truth.

See World War II

Emperor Hirohito After World War II

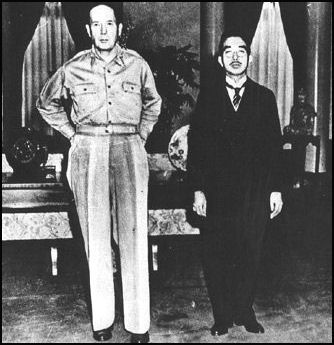

Macarthur and Hirohito Emperor Hirohito came very close to being executed as a World War II war criminal. It may have been the direct intervention of Douglas MacArthur that kept that from happening. Many historian feel than Hirohito bore just as much responsibly for the war as Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, who was executed for war crimes.

Hirohito accepted responsibility for the war and offered to abdicate or do whatever was asked of him. MacArthur wanted him to stay on to make the transition to democracy as smooth and peaceful as possible. Hirohito and MacArthur met 11 times. Hirohito was completely exonerated and used as a unifying symbol in the postwar period similar to way he used during the war.

Hirohito approved the American-made constitution and traveled across the country shaking hands and exchanging bows with ordinary Japanese to boost their morale. Describing one outing, Frank Gibney wrote in Time: "The crumpled gray hat became in time the badge of a successful political campaigner. The monosyllables in which Hirohito had conducted his early interviews with the common folk grew into coherent questions and intelligent replies. The shy man waved his hat in the air to acknowledge greetings. He smiled. Slowly the sense or personality behind the walled moat of the Imperial Palace communicated itself to the people of Japan."

During the same trip one steel worker at a mill visited by Hirohito told Time, "I must admit that we were filled with deep emotion. When you talk about the Emperor, it's just an abstract thing. But when you see him close at hand, it's different, somehow...The Emperor is our father. He should be left a he is."

Americans, Hirohito and War Responsibility

Historian John Dower has argued that Americans created an attitude that has prevented the Japanese from facing up to their culpability in World War II the same way the Germans have. Instead of punishing Hirohito as war criminal MacArthur paid him formal respect as the living symbol of Japan and absolved him of any responsibility for the war.

Dower argued that the absolution of Hirohito made a mockery of the Tokyo war crimes trial in which 23 military and civilian leaders were convicted — with seven executed — for essentially following Hirohito' decrees. "Justice was rendered arbitrarily. Serious engagement with the issue of war responsibility was deflected: if the nation’s supreme secular and spiritual authority bear no responsibility...why should his ordinary subjects be expected to engage on self-reflection?"

Dower added, the Americans kept Hirohito as Emperor because "The Americans said if they forced him to step down, there would have been chaos and rifts in Japan."

Hirohito in the 1960s and 70s

Hirohito at White House with

U.S. President Gerald Ford Hirohito presided over the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and made successful trips to seven countries in Europe in 1971 and to the United States in 1975, when he visited Disneyland and was photographed with Mickey Mouse, .

Hirohito had a "warm relationship" with Liberal Democratic Party Primer Ministers, Eisaku Sato, and Kakauei Tanaka, and was said by some to be manipulated by the tycoons of Japan Inc. He received top-level military briefings even though this violated the constitution through the 1960s and until 1973 when the practice was revealed during the Lockheed Scandal.

Hirohito was a trained marine biologist. On a visit to Washington D.C. in 1975, he became so entranced by a collection of colentrates (hydra, jellyfish, corals and anemones) from around the world, he fell behind on his State department schedule.

Prime Minister Koizumi visits to Yasukuni Shrine — which enshrines Japanese the war criminals — became a big issue in Asia in the early and mid 2000s. Documents released in July 2006 revealed that even Emperor Hirohito was displeased about the enshrinement of the war criminals and felt that visits to Yasukuni Shrine were inappropriate. In diaries of private conversations, Hirohito said he stopped visiting the shrine when it began honoring 14 convicted Class war criminals, including Hideki Tojo, the wartime prime minister, and others who were executed. Hirohito visited the shrine eights times after the end of World War II. His last visit was 1975. Neither he or the government explained why he stopped the visits. The current emperor, Emperor Akihito, has never visited the shrine as Emperor.

Hirohito's Death

Hirohito died on January 7, 1989 of cancer in Tokyo. He became serious ill in 1988 and slowly wasted away for months, with the Japanese media describing his treatment in great detail. An effort was made to make Hirohito live as long as possible so that his ruling year matched up with the calendar year. He died officially on January 6, just as the New Year’s holidays were coming to a close. Before that time, there nightly reports on the evening news on how much blood was given to him to keep him alive.

Hirohito left behind a taxable estate of about $200 million. He is believed to have kept a diary since age 11. The diary, plus his conversations with MacArthur, have never been made public.

After Hirohito's death Empress Nagako became the Empress Dowager Nagako. She was regarded as too senile and feeble to attend the funeral and lived out her life n a modest house on the Imperial Palace ground in Tokyo. She lived to the age of 97 and died in June 2000.

Views of Hirohito After His Death

Pulitzer-Prize-winning

book about Hirohito Hirohito is posthumously named Emperor Showa. Showa means ‘Shining peace.” He died without apologizing for the events in World War II. His birthday, April 29, is still celebrated as holiday although the name was changed to Green Day. In 2005 a bill was passed to call the holiday Showa Day.

In 1990, the mayor of Nagasaki was shot after saying in public that Hirohito bore some responsibility for the war.

In the mid 2000s, an actor played Hirohito in a film about Hirohito — “The Sun” by Russian director Alexander Sokurov — at the close of World War II. It was considered quite revolutionary — in the view of some, sacrilegious — for an actor to play someone once regarded as a god. In older films that dealt with historical events in which he was a central figure he was rarely shown. When he was shown he was shown from the back at a distance.

Image Sources: Wikipedia

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2010