HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM AND RELIGION

Heian-era painting, Five Buddhas

In the Heian period (794 - 1185) Buddhist culture was primarily the property of the court and the aristocracy — a very small minority in Japan. Religion to some extent was separated from politics but Buddhist clergy were very powerful and had close ties with the Imperial family and ruling elite. The conflict between Buddhism and Shinto was dealt with making Shinto gods manifestations of Buddha. Two important Buddhist sects — Tendai and Shingon — were founded by Japanese monks after returning from China.Between 1150 and 1300 new sects and doctrines arose that were founded by reformers. They used simple ideas and lively language that appealed to ordinary farmers, fishermen and soldiers.

The Heian period saw a movement of Buddhism away from government centers and out among the people, although this movement fell far short of a full-scale popularization of the religion. F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “ Buddhism continued to grow during the Heian period, helped by an almost harmonious co-existence with the native Shinto religion and the acceptance of its teachings by the Court. Great religious complexes sprang up in the central provinces, aided by grants of shoen and other land rights. Chief among these was the Enryakuji on Mt. Hiei, to the northeast of the capital. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

The relationship between Mahayana Buddhism, its cortege of buddhas and bodhisattvas, and the Shinto pantheon raised some issues. In the Heian period a theory known as honji-suijaku, or "original nature and provisional manifestation," came to dominate. According to this theory, the local kami of Shinto were manifestations of various buddhas and bodhisattvas that appeared in Japan to teach the people and protect the nation. In this way, both religions could be accommodated in a single institution that incorporated both Buddhist and Shinto personnel and practices (the jinguji, or "shrine-temple"). [Source: A. S. Rosso,; Jones, C. B. New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The most important temple was Enryaku-ji Temple, built on top of Mt. Hiei near Kyoto. Founded in 788 by Saicho, the priest who founded the Tendai school of Buddhism, it was established to protect Kyoto from demons traveling from the northeast and was the center of Buddhism in Japan for 800 years. At it height the temple contained 3,000 buildings, ruling monks more powerful than the Imperial family and warrior monks that supported them. Many famous monks are associated with Enryaku and Mt. Hiei: Honen, founder of the Jodo sect; Eisai, founder of the Zen sect; Dogen, founder of the Soto sect; Shinran, founder of the Jodoshin sect; and Nichiren," founder of the Nichiren sect. [Source: Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS, TEMPLES AND MONKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST SECTS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTOS VERSUS THE TAIRA CLAN IN THE HEIAN PERIOD (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD GOVERNMENT (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD ARISTOCRATIC SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD LIFE factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN THE HEIAN PERIOD factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan WRITING AND LITERATURE IN THE HEIAN PERIOD factsanddetails.com TALE OF GENJI, MURASAKI SHIKIBU AND WOMEN IN THE STORY factsanddetails.com

Websites on Nara- and Heian-Period Japan: Essay on Nara and Heian Periods aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Nara Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the Heian Period Wikipedia ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji Temple Websites: Enryaku-ji Temple official site hieizan.or.jp; Marathon monks Lehigh.edu ; Tale of Genji Sites: The Tale of Genji.org (Good Site) taleofgenji.org ; Nara and Heian Art Sites at the Metropolitan Museum in New York metmuseum.org ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Tokyo National Museum www.tnm.jp/en ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Halo of Golden Light: Imperial Authority and Buddhist Ritual in Heian Japan” by Asuka Sango Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949–1603" by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds Amazon.com; “The Gates of Power: Monks, Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan” by Mikael S. Adolphson Amazon.com; “The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sohei in Japanese History” by Mikael S. Adolphson Amazon.com; “Emperor and Aristocracy in Heian Japan: 10th and 11th centuries” by Francine Herail and Wendy Cobcroft (2013) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 2: Heian Japan” by Donald H. Shively and William H. McCullough Amazon.com; “The Birth of the Samurai: The Development of a Warrior Elite in Early Japanese Society by Andrew Griffiths Amazon.com; “The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan” by Catharina Blomberg Amazon.com; “Buddhism in the Heian period reflected in the Tale of Genji” by Kati Neubauer Amazon.com; “Heian Temples: Byodo-In and Chuson-Ji” (The Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art, V. 9) by Toshio Fukuyama and Ronald K Jones Amazon.com; “The Pillow Book” (Penguin Classics) by Sei Shonagon and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com; “The Tale of Genji” (Penguin Classics) by Royall Tyler and Murasaki Shikibu Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Japanese Arts of the Heian Period, 794-1185" by John M Rosenfield Amazon.com;

Buddhism and the Shift of Power from Nara to Heian

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: In the Nara Period (A.D. 710-794), the Sangha (monk community) began to gain new political power — a process which culminated in an effort to institute a Buddhist theocracy under a master of the Hosso sect. This was finally blocked by opposing forces in the royal court, and at the close of the Nara and the beginning of the Heian period (794 to 1185) the Nara clergy was significantly discredited. Emperor Kammu deliberately undertook to dissociate the court from the Nara schools by moving the capital bodily to Kyoto and adopting the term heian (“peace,” “tranquillity”) to express his new political and cultural goals. He also encouraged the formation of a new Buddhist monastic order, under the leadership of Saicho (767–822), a reforming monk who had earlier withdrawn in disgust from the worldly meshes of Nara Buddhism. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Saicho established his own charismatic and doctrinal independence by studying with Tien-t’ai (Tendai) monks in China. He centered his teaching on the Lotus Sutra and required his monks to undergo 12 years of study and discipline under the rules of the Vinaya. His specific social aim was to prepare them to assume positions of responsible leadership in joint support of the monastic order and the state.

With Kammu’s death in A.D. 806, the new emperor asserted his own patrimonial independence by promoting a new teaching, expounded by Kukai (Kobo Daishi), a monk of aristocratic Japanese lineage who had studied in China and returned with Tantric doctrines culled from the Mantrayana (Chen-yen) school. Kukai, unquestionably a man of immense intellectual and artistic abilities, founded Shingon — the Japanese version of this school. Its esoteric teachings, rich ceremonial, and aesthetically satisfying symbolism appealed to the royal court. Shingon claimed to incorporate not only all the major Buddhist doctrines but also Confucianism, Taoism, and Brahmanism, forming a hierarchial system arranged in ten stages of perfection and capped by the esoteric mysteries. It thus provided an eclectic system of beliefs and practices capable of wide-ranging social penetration, which could be accommodated to the given social hierarchy through extension of the highest esoteric privileges to the elite. Shingon’s synthetic potential also found one of its most important expressions in “dual” Shinto, in which Shinto gods were designated Bodhisattvas in an effort to form a unified cultic framework.

Buddhism, Politics and Government in Heian-Era Japan

Emperor Murakami

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “There was a substantial crossover between the elite monks of the major Buddhist establishments and the court aristocracy. For one thing, members of aristocratic families often became monks, either early in life or after retiring from political office. The major posts in the Buddhist clergy were in part political appointments, usually requiring the support of leading government officials. In no way, however, should these facts imply that the Heian nobility took a cynical view of Buddhism. Remember, we live in a society today that generally regards close ties between church and state as improper. In Heian Japan, however, Buddhism was seen as absolutely essential for the well being of the state, and it was natural that religion and politics would mix. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Consider, for example, the text of the following Buddhist prayer, uttered at a Buddhist ritual by Fujiwara Morosuke, a Minister of the Left with ambitions to place his sub-branch of the Fujiwara family into positions of great power: “Through the power of this [ritual] may the glory of my family be passed on. May the fullness of the glory of the emperor [Morosuke’s son-in-law, Emperor Murakami], the empress [Morosuke’s daughter, Yasuko], the crown prince [Morosuke’s grandson, Prince Norihira], the princes and princesses, the three ranks of officials [including the minister of the left, Morosuke himself], and the nine ranks of courtiers unceasingly persist for generation after generation and fill the court.1

The names of specific individuals are not important here. Instead, notice that this is a prayer by the Minister of the Left for the political success of his immediate family members (which includes the emperor for reasons we examine later). We are a long way from the Buddha’s original teachings.” ~

“Although this particular prayer was uttered by a government official, the larger ritual in which it took place was conducted by a monk--and not just any old monk. The Minister of the Left had selected a rising star of the Buddhist establishment as the head ritualist, and, of course, this selection by the minister furthered the monk’s career even further. This monk was not originally from a powerful family. Instead, his career within the Buddhist establishment rose mainly because of his superb skill as a debater of theological issues. Neil McMullen points out that "in the tenth century there appears to have been a correlation made between knowledge and power. That is, a monk who demonstrated great intelligence was considered to be a prime candidate for patronage because such a monk was believed to be capable of performing especially efficacious rituals."2 One point to be made here is that the Buddhist clergy offered some possibility of social mobility. Because monks perceived as having special powers of the mind or spirit were especially desirable to be employed by powerful officials, a monk who managed to demonstrate such power might advance to high rank despite humble origins. Such advancement was not easy, but it was possible during most of the Heian period. ~

“Toward the end of the Heian period, however, even monastic advancement had become entirely a matter of family connections and status. In other words, the same group of aristocrats staffed both the Buddhist and government hierarchies. They did not necessarily get along well with each other. Infighting within a family and competition between aristocratic families was the rule in Heian Japan because the number of eligible aristocrats greatly exceeded the number of prestigious posts in the bureaucracy or in the Buddhist hierarchy. Especially because the same pool of aristocrats supplied both monks and ministers, conflict between the government and some of the powerful monasteries increased during the last century of the Heian period. Large monasteries maintained armies of warrior monks (sohei), who were usually more warrior than monk. These monastic warriors would sometimes march through the streets of the capital and demand concessions from the government (more land, for example). Usually, the imperial guards dared not resist the warrior monks because the monks carried with them Buddhist relics and other ritual objects believed to possess supernatural power. ~

Buddhism and Power in Heian-Era Japan

Buddhist Guardian deity Governing and religion went hand and hand. Throughout Japanese history, new sects and temples needed government approval to become established. More often than not permission was granted on the basis of grain tax revenues and land than on particular religious beliefs. Buddhist temples were meeting places and their schools were the foundation of the education system. They served as a local government, recording births and deaths, collecting taxes and providing help to the needy.

Religious sects that were viewed as helpful to the government were given beneficial treatment while those that were viewed in unfavorable terms were persecuted. Almost all religious activities, from the number of priests per temple and what was taught in schools, needed government approval.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “In terms of personnel, there was a significant overlap between the leading Buddhist clergy and both the nobility and the imperial family. It was common, for example, for imperial princes to become the heads of the major Buddhist monasteries. Furthermore, emperors and nobles alike often retired from worldly affairs to become Buddhist monks. In many cases, however, they continued to exert political influence even after joining the clergy. Buddhist temples maintained armies of warrior monks and held interests in the special estates mentioned previously. They were, in short, wealthy and powerful, and they often wielded political influence as a result.” [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Increasing Power of Monasteries in Heian Japan

Carl Bielefeldt wrote in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: “The growing autonomy of Buddhism in the Heian period was occasioned not only by the diffusion of the religion to the populace but by the consolidation of power in the monastic centers. Just as the major aristocratic families came increasingly to dominate the court through the independent means provided by their private land holdings, so too certain monasteries acquired extensive property rights that made them significant socioeconomic institutions. As such, they were players in Heian politics, supported by, and in turn supporting, one or another faction at court; as a result, their elite clergy interacted with, and was itself often drawn from the scions of, the aristocracy. This development produced what is often referred to as Heian "aristocratic Buddhism," with its ornate art and architecture, its elegant literary expression, and its elaborate ritual performance. [Source:Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

The Nara monasteries were challenged and often superseded by institutions in and around Heian (modern Kyoto), of which the most historically influential became Enryakuji, on Mount Hiei, and (to a somewhat lesser extent) Toji. The former was the seat of the Tendai school; the latter was the metropolitan base of the Shingon (which had established itself on isolated Mount Koya).

Like Todaiji, Kofukuji, and other major monasteries, these institutions not only held significant land rights but developed networks of subsidiary temples that made them, in effect, the headquarters of extended organizations. The identity of the Tendai and Shingon organizations was ritually reinforced by the adoption of new, private rites of ordination (tokudo) and initiation (kanjo) that supplemented and in some cases even replaced the standard rituals of Buddhist clerical practice. Thus, the first steps were taken toward a division of the Buddhist community into ritually distinct and institutionally separate ecclesiastic bodies.

Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji Temple

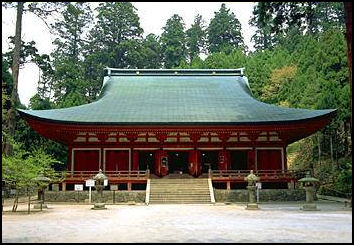

Mt. Hiei (on a ridge between northern Kyoto and Lake Biwa) is regarded as one of three holiest mountains in Japan along with Mt. Koya and Mt. Osorezan. More than 800 meters high, it has several beautiful temples scattered over a wide area in a pine forest. In the old days the mountainside was filled with temples and monks and is regarded as the mother mountain of Japanese Buddhism.

building at Enryakuji Temple Enryaku-ji Temple is a temple complex with halls, pagodas and other buildings on top of Mt. Hiei grouped into three main sections. Todo (Eastern Section), Saito (Western Section) and Yokawa. Todo contains the main temple. Saito features tall trees and stone pathways. Founded in 788 by Saicho, the priest who founded the Tendai school of Buddhism, it was established to protect Kyoto from demons traveling from the northeast and was the center of Buddhism in Japan for 800 years.

At its height Enryaku-ji Temple contained 3,000 buildings and the ruling monks that resided there had more power than the Imperial family and had armies of warrior monks to support them. In 1581, the ruling shogun saw the temple as threat and ordered nearly all of the temple buildings and the monks destroyed. Many famous monks are associated with Enryaku and Mt. Hiei: Honen, founder of the Jodo sect; Eisai, founder of the Zen sect; Dogen, founder of the Soto sect; Shinran, founder of the Jodoshin sect; and Nichiren, founder of the Nichiren sect.

Heian Period Buddhist Sects

The main Japanese Buddhist sects — Shingon, Tendai, Pure Land Nichiren, and Zen — sprung up during the Heian Period (794-1185) and Kamakura Period (1192-1338). The first homegrown Buddhist sects to take hold in Japan were the Tendai and Shingon schools.

Buddhism began to spread throughout Japan during the Heian period, primarily through two major esoteric sects, Tendai (Heavenly Terrace) and Shingon (True Word).Tendai originated in China and is based on the Lotus Sutra, one of the most important sutras of Mahayana Buddhism. Shingon is an indigenous sect with close affiliations to original Indian, Tibetan, and Chinese Buddhist thought founded by Kukai (also called Kobo Daishi). A third school emerged at the end of the Heian Period. The monk Hônen (1133-1212), a former priest of the Enryakuji, founded what would become known as the Jodo, or Pure Land.

Tendai and Shingon schools were the most influential sects during the Heian period. They emphasized meditative practices using mandalas (elaborate pictorial representations of the Buddhist cosmos, the many heavens, and their inhabitants) and mantras (magically powerful words or phrases). The recitation of the nembutsu, a simple expression of faith in the saving power of the bodhisattva Amida, grew in popularity, as did the Heart Sutra and the Lotus Sutra. Buddhist teachings, practices, and miracle stories were disseminated not only by ordained monks and nuns but also by a variety of associated lay figures. [Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Emperor Saga

A close relationship developed between the Tendai monastery complex on Mount Hiei and the imperial court in its new capital at the foot of the mountain. As a result, Tendai emphasized great reverence for the emperor and the nation. [Source: Library of Congress]

Tendai

The Tendai sect is an eclectic form of Buddhism that incorporates elements of both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. The Lotus Sutra is Tendai’s central text. Followers believe that salvation can be achieved by reciting and copying it. The Tendai sect appeared at the end of the 8th century and was centered at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei near Kyoto.Its founder, Saicho (762-822), studied meditation, tantric rituals and the Lotus sutra in China.

Under the patronage of Emperor Kanmu (737-806) and Emperor Saga (786-842) the Tendai sect was officially sanctioned. It was embraced by these emperors who had tired of the authoritarian nature and political power of the priests in the Nara Buddhist sects. Priest were ordained at Enryakuji, the temple founded by Saicho, Tendai artists produced wonderful Buddhist sculpture---graceful and beautiful sculptures of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and deities---in the Heian period.

Tendai was not recognized as a school until after Saicho’s death. After Mt. Hiei received the right to ordain monks the sect took off, At it height Mt, Heie boasted 3,000 temples and 30,000 monks and produced wonderful works of art. The monasteries kept armed retainers and sometimes imposed their will on the government by force.

Almost every sects has its origins in Enryakuji Temple on Mt, Heie. All new sects founded in the 12th and 13th centuries were founded by Tendai monks. Pure Land, Zen and Nichiren all developed from the Tendai school.

See TENDAI SCHOOL OF BUDDHISM: SAICHO, HISTORY, BELIEFS factsanddetails.com

Shingon and Kukai

Kukai (Kobo Daishi)

Shingon is an indigenous Japanese Buddhist sect with close affiliations to original Indian, Tibetan, and Chinese Buddhist thought founded by Kukai (also called Kobo Daishi). Kukai greatly impressed the emperors who succeeded Emperor Kammu (782-806), and also generations of Japanese, not only with his holiness but also with his poetry, calligraphy, painting, and sculpture. [Source: Library of Congress]

Shingon Buddhism (whose name was derived for the Sanskrit word for "magic formula" or "mantra") is centered at Kongobu-ji Temple at Mt. Koya and To-ji Temple in Kyoto. It is closely linked with the Tendai sect and is known for its ornate art and incorporation of Shinto elements.

F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “Shingon (or True Word) was centered on the worship of Maha-Vairocana (or Great Illuminator, otherwise known as the Dainichi Nyorai), believed to be the first and greatest of the Buddhas. Shingon held that the Dainichi Nyori was present in all things in the universe and by extension was all people. Essentially, Kukai taught that to understand the Great illuminator, one needed to unlock the mysteries of their own minds and spirits. This involved a large amount of ceremony and ritual - hence earning Shingon the label of 'esoteric Buddhism'. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

Shingon Buddhism has Tantric elements and is known for it rich ceremonies and has many similarities with Tibetan Buddhism. A central idea is to find the "mystery at the heart of the uncovered” using rituals, symbols and mandalas representing the sphere of the indestructible and the womb of the world.

Kukai (774-835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism, is one of Japan’s most beloved religious figures. Kukai established the teachings of Shingon esoteric Buddhism in Japan in the early Heian period (794-1192). Often referred to by his posthumous name, Kobo Daishi, he is considered a giant of the esoteric Buddhist school who had a great impact on Buddhist art in Japan.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Kūkai (774-835), posthumously titled Kōbō Daishi (The Great Master of the Extensive Dharma), was the founder of the Shingon or “True Word” Japanese school of Buddhism and is considered one of the most important intellectual and cultural figures in Japan. Kūkai traveled to China in 804 and went as far west as the Tang dynasty capital of Changan (today, Xian), where he was introduced to the esoteric Buddhist tradition. Upon returning to Japan two years later, he founded a Shingon temple on Mt. Kōya as well as Tōji temple in Kyoto. His main treatise is the Jūjū Shinron (Treatise of the Ten Stages of Mind). [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

See Separate Article SHINGON AND KUKAI factsanddetails.com

Pure Land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism (also known as Jodo, Jodoshu, or Jodoshinshu) spread during the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333) but was introduced by the Chinese to Japan much earlier. Founded by Honen and Shinran, it emphasizes faith in the saving grace of Amida, another enlightened being, rather than through meditation. The School of Pure Land emerged about A.D. 500 in China as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

Jodo in Japan emerged at the end of the Heian Period. F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “ Jodo popularized Amidism, a form of Buddhism the monk Genshin (942-1017) had written about and that centered on the worship of the Amida Buddha. The Amida resided in the Western Paradise and welcomed in all the faithful. No undo ceremony or spiritual honing was necessary for admittance to Paradise, only a honest belief in the Buddha and the reciting of his name in praise (the nembutsu). By the start of the Kamakura Period, Jôdo would have a strong following among the common people, for whom its straightforward approach appealed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the established schools of Buddhism did not take kindly to Jôdo, and made very effort to limit its spread. Yet by the 15th and 16th centuries, Jôdo was to prove an exceptionally powerful force. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ]

The School of Pure Land takes the Mahayana belief in Buddhas or Bodhisattvas a step further than Buddhist traditionalists want to go by giving Bodhisattvas the power to help people attain enlightenment that otherwise would be unable to attain it on their own. The emphasis on Bodhisattvas is manifested in the numerous depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Pure Land temples and caves.

Pure Land Buddhists reveres Amida (literally meaning “infinite light” or “infinite life”), the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and stress the universality of salvation. They believe that salvation is achieved through faith rather than good works and that Buddha and heaven are close at hand and everywhere rather in some far off place as Buddhists had been taught to believe.

Pure Land Buddhists believe that Buddhism has entered a Mappo (Later Age) in which Buddhism is in decline and individuals are no longer able to achieve enlightenment on their own and salvation can only be achieved by enlightenment through the mercy of Amida. This idea appealed to many ordinary Japanese who were not turned on by the usual process of mediating, chanting and denying oneself for long periods of time.

See Separate Article PURE LAND BUDDHISM (JODO) factsanddetails.com

Honen Illustrated biography

Honen and Shinran

Honen (1133-1212) was the founder of the Jōdō (Pure Land) sect in Japan. He the Japanese man who made Pure Land Buddhism an independent sect, eschewed scholarly metaphysics and promoted the use of simple prayers and chants such as "Hail Amida Buddha," as a means to enlightenment. He once said "Even a bad man will be received in Buddha’s Land, but how much more a good man!" The idea of hell and judges is important in the Pure Land school of Buddhism.

Honen studied as a Tendai monk at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei, beginning at age 13, and read the Chinese Tripitaka five times and was respected for his learning. He began teaching the Pure Land faith after realizing, at age 43, that the teachings of the Buddhist elite were lacking and that reliance on Amida was the only way to reach enlightenment and it was something that could be obtained by anyone not just pious monks. This message appealed to both the elite and ordinary people but was opposed by the old schools. Honen and his followers were persecuted. At the age of 75 Honen was banished to Shikoku. Some of his followers were executed.

Shinran (1173-1263) was one Honen’s favorite disciples. Regarded as the actual founder of the Pure Land sect in Japan, he broke free from his teacher and established the Jōdō Shinshū (The True Teaching of the Pure Land). Shinran renounced the monk’s life and married a young noblewoman, arguing that celibacy and dietary rules demonstrated reliance on self-power. He was banished and spent much of his life in the provinces. His grandson carried on his lineages, which remains alive among his descendants today.

Buddhist Militarism and Power in Japan

There was a militant side to Japanese Buddhism. Many monasteries were fortified and had standing armies. These measures began as protective measures against brigands and marauding armies but over time led to the sects becoming like feudal states, sometimes with large armies and controlling entire provinces.

Until the 12th century, Buddhism was closely associated with the aristocracy’s strategy of centralizing political control. Temple such as Kofukuji in Nara, Enryakuji in Kyoto and Koyasan south of Nara held a great deal of power. Religious leaders, court nobles and military leaders competed with one another and formed alliances. Temples earned money from taxes and donations, intended to support monks and maintain buildings.

Monks worked as soldiers and formed power networks with the imperial court and influential members of the nobility. It was not uncommon for violence to occur between monks and warriors over conflicts between temples and the Imperial court. The Buddhist monk Shunkan (1142-1179) is a tragic figure in Japanese history. As punishment for his failed plot against the ruling Heike clan, he was exiled to Iojima island, south of Kagoshima, Kyushu. He was left alone on the island after his conspirators were granted amnesty and is believed to have committed suicide. His story is the basis of a famous Noh play.

Enryaku Power and Warrior Monks

Enryakuji Temple F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “Enryakuji grew throughout the Heian period to include thousands of buildings and to hold considerable influence as the vanguard of Tendai Buddhism. As the monastic complex grew, so did the willingness of its inhabitants to actively involve themselves in temporal affairs, or rather, to deal with issues in a very temporal manner. The early rivals of the Enryakuji included the older Nara temples, and, after the 10th Century, the Mii-dera temple. The latter came about as a result of a schism with the Tendai sect of Buddhism that saw a fair number of monks driven from Mt. Hiei and forced to establish their own place of worship. Outright battles between the Enryakuji and Mii-dera were common during the later Heian Period, and saw the later burned to the ground numerous times. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

The famous warrior monks, or Sohei, of Mt. Hiei came about, it would seem, in an unexpected way. From its earliest times, the Enryakuji was held to be off limits to both women and law enforcement bodies. The latter prohibition attracted such a large criminal element to Mt. Hiei that Kakûjin (1012-81), the 35th abbot of the Enryakuji, called for his followers to form an army and drive away the undesirables. In fact, many of the men who took up arms may well have been those very same unwelcome fugitives they were intended to fight. From this time forward, Mt. Hiei would maintain a martial arm, one that it rarely hesitated to use. |~|

One frequent victim of the Enryakuji’s heavy-handed tactics was none other then the emperor himself. As emperor Shirakawa is alleged to have said, "There are three things that even I cannot control: the waters of the Kamo river, the roll of the dice, and the monks of the mountain." When the monks of Mt. Hiei found themselves at odds with court over some affair (perhaps a question of land rights or taxation), they would gather and march down at to the gates of Kyoto, bearing on their shoulders the sacred palanquin (mikoshi) of the Shinto deity Sanno. So revered was this artifact that no one dared block its passage and much more often then not the emperor would give in to the monk’s demands. The warrior monks of the Enryakuji would continue to play an important role in the Kyoto area for hundreds of years, until the advent of Oda Nobunaga. While evidently not the first monastic complex to take on a military aspect, the Enryakuji’s reputation was great indeed.

Buddhist Conflicts and Feudal Wars in the Heian Period

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: Tendai was victimized by a sectarian disruption stemming principally from a dispute over the right of patriarchal succession which developed when the emperor selected a blood relative of the aristocratic Kukai as abbot of the order. The conflict produced one of the most tragic periods in the history of Japanese Buddhism. The two camps not only split into hostile religious sects but also, in coordination with dominant clan-based feudal developments, formed fortresses of warrior-monks, who engaged in violent internecine warfare. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Fighting Monk

During the medieval period this became a widespread characteristic. These hostilities were exacerbated by the fact that personal prestige and political status depended jointly on education in one of the monasteries and the monastery’s respective position vis-à-vis royal or clan approval. Clan conflict was frequently defined along sectarian lines, with the great families supporting one feudal monastery against another. Equally important was the freewheeling legitimation allowed by the syncretic richness of the esoteric teachings — including suitable Shinto deities to signify the solidarity of each monastic fortress. The esoteric repertoire also gave rise to the Vajrayana sexual sacramentalism of the Tachikawa school — a “heretical” movement bitterly opposed by Shingon leaders and ultimately suppressed by imperial order.

In all of this the resurgent Buddhism of the early Heian seemed to have undergone a compromising worldly domestication. However, toward the end of the Heian period, amid increasingly violent clan wars and social disruptions, there were countervailing forces at work. In the Heian court, clearly under the influence of Buddhism, we find the emergence of a self-reflective poetry, literature, and drama marked by an extraordinary sophistication of mood and expression. Awareness of the transience of life and the melancholy of impermanent beauty was coupled with symbolism of withdrawal and a nostalgia for the tranquillity of the past. This easily degenerated into sentimentality and became a sign of courtly refinement, but nevertheless it signified a growing uneasiness and a renewed sense of human finitude and guilt.

The feudal wars finally resulted in the overthrow of the old Kyoto aristocracy and the installation of military rule under the Kamakura shogunate (1192–1333). However, effective stabilization of the society did not take place until the Tokugawa period, and during the intervening four centuries Japan continued to be devastated by protracted warfare. In this situation of deepening gloom and pessimism the energies of Buddhism were once again restored, in a new breakthrough which touched all social strata. Liberated from aristocratic ties to the defunct Kyoto court, it expressed its inherent universalism in ways which still dominate Japanese religious life today. The most important new movement was Pure Land Buddhism. The soteriology was basically the same as in the Chinese case. Self-salvation is impossible. The single efficacious act is the Nembutsu, the invocation and fervent repetition of Amida’s (Amitabha’s) name — a practice already introduced earlier by Ennin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Guardian deity, Ray Kinnane.

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated January 2024