INTRODUCTION OF BUDDHISM TO JAPAN

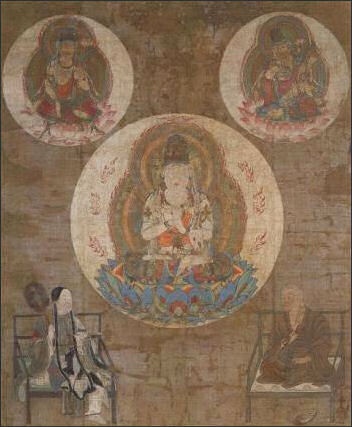

Gosonzo (Horyuji)

The arrival of Buddhism and its gradual acceptance by elite members of society was an important factor in the early cultural and political development of Japan. Buddhism is believed to have been first introduced to Japan in A.D. 538 along with the Chinese language, Chinese ideographs and Buddhist styles of painting, sculpture and architecture — via Korea when a Korean ruler (a king of Paekche) attempting to form an alliance with the Yamato clan sent a Buddha statue and some Buddhist texts as a gift. Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) Buddhism was the school of Buddhism that was introduced.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Along with Buddhism, other important foreign concepts and practices, including the Chinese written language, the practice of recording history, the use of coins, and the standardization of weights and measures–all of which supported the creation of a single-ruler state based on the Chinese model of a centralized, bureaucratic government–were imported from China and Korea. Taken together, these imports had a profound impact on all aspects of apanese society. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Artmetmuseum.org \^/]

It is thought that Buddhism was first publicly introduced in the seventh year of Emperor Kinmei’s reign, when King Songmyong of the south-western Korean state of Paekche (Japanese pronunciation: Kudara) presented Buddhist images and sutras to the Japanese court. The Soga clan, possessed of wealth and influence at that time, gave its positive support to the new religion,and Buddhism gradually spread among the imperial house and other influential families. [Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

It is important to note that, for its first few centuries in the Japanese islands, Buddhism functioned as a set of ritual practices of power to be used for political purposes. Japanese Buddhists generally had little knowledge of the fine points of theology or Buddhist spirituality until well into the Heian period. And it was not until the Kamakura period that Buddhism became a major religion among common people. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS, TEMPLES AND MONKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST SECTS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; PRINCE SHOTOKU factsanddetails.com; TAIKA REFORMS AND EMPERORS TENJI AND TENMU factsanddetails.com; ASUKA GOVERNMENT AND ECONOMY AND THE RITSURYO SYSTEM factsanddetails.com; ASUKA, FUJIWARA AND ASUKA-ERA CITIES AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; CULTURE AND LITERATURE FROM THE ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ARCHITECTURE: PALACES AND BUDDHIST TEMPLES factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ART factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan” (2008) by Donald F. McCallum Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Plotting the Prince: Shotoku Cults and the Mapping of Medieval Japanese Buddhism” by Kevin Gray Carr Amazon.com; “Nihongi: Volume I - Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697" by W G Aston Amazon.com; “The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters” by no Yasumaro Ō and Gustav Heldt Amazon.com; “Man'yoshu” by Alexander Vovin Amazon.com; “Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan” by William Wayne Farris Amazon.com;“The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Early History of Buddhism in Japan

King Songmyong (Emperor Kinmei) of the Paekche Kingdom in Korea

The first known reference to Buddhism in Japanese chronicles is dated to A.D. 538. King Songmyong of Paekche was threatened militarily by Silla, another Korean kingdom. The threat was so serious he had to move Paekche’s capital to a safer location. King Songmyong sought military assistance from the powerful clans in the Yamato region in present-day Japan, and, in connection with this matter, sent a Buddhist statue and several volumes of Buddhist scripture to Kinmei, the head of the Yamato confederation. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

An account in the Nihon Shoki said that King Songmyong sent a high level envoy to obtain support from Asuka Emperor Kinmei. During a second mission, the Asuka leader was presented with an image of Shaka Butsu in gold and copper, several flags and umbrellas and a number of volumes of Buddhist sutra texts. Along with the gifts, came a message boasting that embracing Buddhist teachings would bestow upon him, “treasures to his heart’s content”. The message urged the Yamato Emperor to receive Buddhism’s teachings, by offering the enticement that wealth, wisdom and the fulfilment of all one’s wishes beckoned the believer.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

In a message about Buddhism sent with gifts, King Songmyong stated: “This doctrine [Buddhism] is amongst all doctrines the most excellent, but it is hard to explain and hard to comprehend. Even the Duke of Zhou and Confucius had not attained knowledge of it. This doctrine can create religious merit and rewards without measure and without bounds, and so lead to a full appreciation of higher wisdom. Imagine a man in possession of treasures to his hearts content, so that he might satisfy all his wishes in proportion as he used them. Thus it is with the treasure of this wonderful doctrine. Every prayer is fulfilled and nothing is wanting. Moreover, from distant India it has extended here to the three [kingdoms of Korea], where there are none who do not receive it with reverence as it is preached to them. [Source: W.G. Aston’s translation of Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from Earliest Times to A.D. 697 (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972), p. 66, ~]

There is a slightly different account in the records of Gango-ji engi (compiled earlier than Nihon shoki). In an account that conflicts with the Nihon shoki’s account, the Buddhist relics and priests were presented to the imperial court in response to a request sent to Paekche (likely by Soga no Umako). Historians interpret this as meaning that the Nihon shoki embellished the account of the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. However, the scholars also generally concur that King Songmyong of Paekche did in fact send Buddhist images and texts to the Yamato king sometime between 538 and 552. And from that time on, a steady stream of representatives from Paekche brought various Buddhist images, ritual objects and sutra texts.

Buddhism at the Time It Arrived in Japan

Chinese Buddhist statue

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: “Buddhism arrived rather late in Japan in the middle of the 6th century, along with Korean and Chinese priests … one thousand years after the religion had originated with Siddhartha Gautama in India. From India, Buddhism had moved eastward through China, Southeast Asia and Korea before finally arriving in Japan. Archaeologists have traced the path of Buddhism to Japan through examining excavated temple tiles of the 6th century. From their studies, Buddhism was transmitted from south China’s court of Liang through the south Korean state of Paekche to Japan. Thus the earliest version of Buddhism Japan received was a south China variety and it was spread by way of Paekche which was in its Golden Age of Buddhism then. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “It is important to notice the view of Buddhism presented here. The Buddhism of King Songmyong’s court was not a spiritual discipline. To the Paekche king, Buddhism was a powerful form of magic, a set of esoteric practices that rulers could employ as a potent supplement to their power. For him, Buddhism was a set of practices that would allow one to "satisfy all his wishes," not to eliminate them as was the basic teaching of Buddhism as it originated in the Indian subcontinent. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“At this time, and for several centuries afterward, most Korean elites regarded Buddhism as a device for strengthening the power of the state. In early Japan, too, the dominant view of Buddhism regarded it as a potent form of magic for use by the state for its own political ends. This view of Buddhism, of course, runs contrary to the original teachings of the Buddha, but, just as Confucianism changed in ways Confucius would not have approved of or even recognized, so too did Buddhism change. It was not until the late Heian period that Buddhism began to spread into the ranks of ordinary people as a significant religious or spiritual force.” ~

Early Buddhism Versus Shinto in Japan

Buddhist sculpture from Horyuji in Nara, Japan

Buddhism contained many ideas and images that were radically different from the concerns of native Shinto. At first Buddhism was rejected by Shinto priests on the grounds that it embraced foreign kami (spirits or deities), but later it was accepted by members of the Japanese court. Kawagoe wrote: “The first encounters with Buddhism did not go down well with all. Buddhism was considered by many clans as an alien cultural invasion and was thought embracing this foreign religion that would offend the local kami gods. Soga no Iname, chief of the immigrant clan group is recorded in the Nihon shoki as having argued for its introduction, “All neighboring states to the west already honor Buddha. Is it right that Japan alone should turn its back on this religion?” And two other high ministers, chiefs of native clans were recorded to have objected to its introduction saying,” The kings of this country have always conducted seasonal rites in honor of the many heavenly and earthly kami of land and grain. If [our] king should now honor the kami of neighboring states, we fear that this country’s kami would be angered.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“According to the account, just as Emperor Kinmei had first introduced Buddhist rituals, an epidemic hit Japan so that the new religion was blamed for incurring the wrath of the native kami gods. Emperor Kinmei was forced to appease the kami by having the Buddhist statues thrown into the Naniwa Canal and a recently constructed pagoda burned to the ground. The Nihon shoki reports the events dramatically, saying that on that day, the winds blew and rain fell under a clear sky.

“However, there is a slightly different account in the records of Gango-ji engi. It places the suppression of Buddhism as having happened in 569 and linked it to the execution of Soga no Iname in the closing months of Kimmei’s reign, not due to the pestilence outbreak. According to Gango-ji engi, the call to purge the capital of Buddhism did not come from the two anti–Buddhist ministers but from Emperor Bidatsu himself. As the chief of kami worship, the Emperor, not his ministers would have been responsible for the priestly rulers in the native segment of society. Adjusting for the Gango-ji- engi version of events suggests that the promotion of Buddhism declined with the demise of Soga no Iname, not because of the outbreak of pestilence. ...It is also thought that the presentation of the Buddhist texts and statues was followed by conflict over its acceptance and that Soga no Iname had pushed for the official adoption of Buddhism...The important question remains what was really at the heart of the quarrel between Soga and other factions over the acceptance of Buddhism?

“Despite the initial rejection of Buddhism, ancient belief and deep tradition that the kami possessed the power to benefit life here and now, paradoxically, made the Japanese more receptive to Buddhist rites that would bring rain and secure a good harvest, stop disease and pestilence and cure illness, or prosper the state. The indigenous kami belief system fostered Japan’s receptivity to magical and popular forms of Buddhism.

Early Debate and Struggles Over Adopting Buddhism in Japan

Soga-no-Iname

When Japanese Kinmei received Buddhist gifts from Paekche he "leapt for joy" the ancient chronicles said. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: He consulted with the heads of the other Yamato clans about the best course of action. Soga-no-Iname was head of the Soga uji [clan], an increasingly powerful clan of relatively recent immigrants from the Korean peninsula. He argued that Kinmei should worship the Buddhist image, saying: "All the Western frontier lands without exception worship it. Shall Yamato alone refuse to do so?" [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

The head of the older Mononobe clan argued against worshiping the Buddhist image, saying to do so would offend the local Japanese deities: “Those who have ruled the empire in this our state have always made it their care to worship in spring, summer, autumn and winter the 180 deities of heaven and earth, and the deities of the land and of grain. If just at this time we were to worship foreign deities in their stead, it may be feared that we should incur the wrath of our local deities.” (Adapted from Aston, Nihongi, pp. 66-67.) ~

On the surface it seemed the Soga favored trying the new, apparently powerful foreign religion while Mononobe resisted but there was more to it than that. “Beneath the surface of this religious issue was a struggle for political power between two strong clans. As relatively recent immigrants from the Korean peninsula, the Soga had weaker ties to the native religious practices of the Japanese islands. They supported the introduction of new technology from the continent, which in this case included Buddhism. In the struggle for power in the Yamato heartland, the Soga aligned themselves with continental innovations. The Mononobe, on the other hand, traced their roots back to the Japanese islands, not the Korean peninsula. In its struggle for power with the Soga, the Mononobe aligned itself with the religious and cultural traditions of its native place. Had the Mononobe favored the importation of Buddhism, such a stance would likely have strengthened the hand of the Soga because they were in a better position to act as cultural mediators between the Japanese islands and the Korean peninsula.” ~

Soga Clan Embraces Buddhism

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Kinmei decided to give the statue to Soga-no-Iname for his clan to worship as an "experiment." Kinmei apparently wanted to proceed with caution before taking a stand on the matter. The Soga uji accepted the image and began worshiping it. Daigan and Alicia Matsunaga point out the nature of this Soga acceptance of Buddhism: "The Soga acceptance of Buddhism was far from a conversion in our ordinary sense of the term. They had no philosophical understanding of the new religion and merely regarded it as a superior form of magic long practiced by advanced civilizations they respected and sought to emulate." [Source: Daigan and Alicia Matsunaga, Foundation of Japanese Buddhism Volume 1: The Aristocratic Age (Los Angeles: Buddhist Books International, 1974], p. 10.); “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“Soga worship of the image caused controversy, and Buddhism went through several ups and downs as a result. The conflict finally came to a head in 587, when the Soga and Mononobe assembled their soldiers and fought it out on the battlefield. The Soga won. Soon afterward, the victorious uji brought in Buddhist monks, nuns, relics (sacred remains), temple builders, and related artisans. These specialists came mainly from the Korean peninsula. They began work on a great temple, Asuka-dera, which was completed in 596. Soon, the other major uji began to construct temples for their own benefit. As a result of these actions, Buddhism took firm root in Japan. By the close of the Asuka period (named after the temple), it was, for all practical purposes, the official religion of the state. “ Note here the high degree of independence the powerful Yamato clans exercised. The Emperor and Imperial faction lacked the power to keep the major clans from fighting each other. There was no strong, centralized Japanese state until the time of Tenmu. ~

Soga Clan

Early Buddhism and Politics in Japan

Buddhism’s acceptance rose and fell in the early years based on political factionalism and struggles and Buddhism’s perceived role in natural disasters and good and bad harvests. Buddhism spread quickly among the upper classes after the influential and pro-Buddhist Soga family crushed anti-Buddhist factions. Kawagoe wrote: These events were in effect a showdown between the mainstream native clans and communities engaged in agriculture and agricultural kami worship versus the less numerous immigrant clan groups led by the Soga family that enjoyed the benefits of imported continental techniques and learning associated with the imported Buddhist religion. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“Scholars now regard those pre-645 initial years of Buddhism, as a period when the spread and sponsorship of the Soga Buddhism benefited largely Soga and his immigrant clans, especially since the building of the first ujidera temple complexes were sponsored and controlled by the clans. They also think that until 645, no imperial ruler (including Empresses Suiko and Kogyoku) had actively patronized or been involved in Buddhist worship. Soga’s Asukadera temple was at the centre of the emerging temple complex system dominating the heart of the new capital Asuka. The forty six temples were concentrated in and around the Nara basin where the immigrant clans were based. The new religion was clearly a symbol and statement of the wealth and power of the Soga clan — was Empress Suiko (or other imperial rulers) wary that a developing Buddhist state religion with spiritual authority in the hands of the Soga head patron and high priest of Buddhism could overwhelm the imperial clan’s divine authority that had gone unchallenged for so long in the Kofun-Yamato centuries?

Although Empress Suiko was credited in the Nihon shoki as having been a supporter Buddhism, she appears to have kept the conflict in mind from her “command” to properly carry on the responsibilities of kami worship in an edict issued in 607: “We have heard how our imperial ancestors ruled the land in ancient times. Descending from heaven to earth, they devoutly honored heavenly and earthly kami. They worshipped [kami residing] in mountains and rivers everywhere and were in mysterious communion with heavenly and earthly kami. By performing rites to kami and by worshiping and communing with them in this way, our imperial ancestors harmonized negative and positive forces [on’yo] and handled affairs in accord with [those forces and the will of the kami]. Now in our reign nothing should be done to anger the heavenly and earthly kami by the way in which we honor and worship them. So we hereby command that our ministers work together devoutly in the worship of heavenly and earthly kami.”

“Although Buddhism proliferated due to the support of immigrant clans, especially the Soga clan, it was also partly due to increasingly popular belief that Buddhist rites had a mysterious power to produce spectacular physical and concrete benefits for the community. According to the Nihon shoki, a thousand men and women were conscripted to the Buddhist priesthood when Soga no Umako became ill in 623 “for his sake”. And during the drought of 642 the reading of excerpts from Mahayana sutras at Buddhist temples were offered as prayers, when offerings and prayers to kami produced no rain. The Nihon shoki reported that the reading of excerpts was discontinued because rain fell the next day.

Early Buddhism in Japan and Struggles Involving the Soga Clan

fight between Soga brothers

Conflicts and arguments over Buddhism sparked off fierce battles between the strongest clans and supporters behind the imperial government. Kawagoe wrote: In 587 when the Soga clan supporters of Buddhism won in the battle of the clans and defeated the native Monobe clan which had opposed the introduction of Buddhism. But there remained a divided society with two different sources of spiritual authority and the clashes between the Soga and imperial clans showed the fundamental differences between the two segments of Japanese society...Nevetheless with the defeat of the Monobe clan, the Soga clan grew more powerful and prospered, pushing for the spread of Buddhism. Buddhism spread rapidly between 587 and 645. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Soga no Emishi and his son Soga no Iruka engineered the tragic end of Prince Shotoku’s son Prince Yamashiro Why had the Soga clan so violently opposed Prince Yamashiro imminent succession to the throne, when he was allegedly a devout believer of the Buddhism? A probable motive for the murder, it is supposed that, is that the Sogas realized an emperor who would be committed to the cause of Buddism would divest sacred authority away from the current chieftain of the Soga clan to the emperor. In any event, Soga’s assassination of Prince Yamashiro in turn kindled a coup in which Soga no Emishi and Emperor Kotoku ascended the throne and began to be a patron of Buddhism, following the path outlined by Prince Shotoku. The conflict also showed how the strength of kami worship had pervaded all aspects of life in the native segment of Japanese society, and the entrenched role of imperial rulers as hereditary priests and priestesses of kami worship.”

Soga no Iruka was the early great power of the Asuka Period who even overshadowed the Imperial family. He was assassinated in the well-known coup d’etat of Taika no Kaishin (Taika Reform) in A.D. 645. Learning of his son’s death, Soga no Emishi set fire to his residence and killed himself. According to the Nihon Shoki, in November 644, Soga Oomi Emishi and his son Iruka, built houses in Amakashinooka, with Oomi’s house called Kami no Mikado and Iruka’s Hazama no Mikado. In June 645, the day after Iruka was assassinated, Emishi burned his and Iruka’s houses and committed suicide, the chronicle says. Kyoto University of Education Prof. Atsumu Wada said the Taika Reform was the biggest power struggle of ancient times in which the Sogas, who wielded tremendous power, were killed off and the Imperial family codified laws. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 15, 2005; Japan Times Weekly: Nov. 19, 2005]

Wave of Buddhist Temple Building n Asuka-Era Japan

By 624, there were forty-six Buddhist temple compounds throughout the Japanese islands and nearly 1,400 Buddhist monks and nuns, most of Korean origin. Japanese and immigrant Korean artisans began producing high-quality Buddhist. In many ways it seems that Japanese mastered art of Buddhism before absorbing the main points of Buddhist doctrines, scripture and theology. In the Asuka period, it was the external and ritualistic aspects of Buddhism that caught the attention of Japanese that embraced the religion. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Horyu-ji Temple

Kawagoe wrote: Late in the 6th century, the Soga clan chief Umako had ordered the building of the grand temple Hokoji (known as Asukadera today) on his home territory in Asuka as an outward show of the Soga clan’s support for Buddhism. The foundation of Hokoji (or Asukadera) contained jewels, horse trappings and gold and silver baubles … the same sort of prestige goods previously buried in the mounded tombs of the earlier era. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“The frenetic tomb construction activity of the previous era abruptly ended and all energies were now channeled into temple building by leaders of the day instead. Ancient records tell us that they “vied with one another in erecting Buddhist shrines for the benefit of their Lords and parents.” As Buddhism spread and took hold in society, Empress Suiko’s government established offices to oversee the religious community, putting trusted priests in charge, usually immigrant priests. During Empress Suiko’s reign in 623 a religious census was carried out which reported the existence of 46 temples, 816 priests and 569 nuns.

“As Prince Shotoku came to rule at the helm of government, serving as regent to the Empress Suiko, he ordered the building of the Ikarugji — later renamed Horyuji Temple, which became one of the most ancient and cherished icons of Buddist culture in the nation. It is famous as the oldest wooden structure in existence in the world today. The architecture of and sculptures of Horyuji reveal the extensive international influence that Buddhist teachings had in Asuka’s heyday. The temple art and architecture reveal that Buddhism brought to Asuka a cosmopolitan culture, such as medicine, irrigation, engineering technologies and ways of thought that were modern for those days. Buddhism was a significant force that had provided a channel of contact with the culturally and technologically advanced peoples of the Asian continent.

“By the 640s, Nihon Shoki records that Emperor Kotoku decreed that priests must be properly instructed in Buddhist doctrine and assistance given where needed to maintain all temples erected by members of the titled elite. He called for the Temple Commissioners and Chief Priests to be appointed, who would make a circuit to all the temples and who would make detailed reports to the imperial government, including matters such as their acreage of cultivated lands. Since many of the temples had been established by leaders of powerful uji clan groups, the imperial government had discovered that the key means of controlling the uji chiefs was to control the temples.”

“Buddhism thus took root in Japan, and came to be valued by ruling factions not just as a matter of faith, but because it was viewed as an expedient political tool as well as a shield from the epidemics of illness and natural disaster of the times. In the following decades, Buddhism continued to enjoy the support of the central government and newer, grander and more richly endowed temples were built, staffed by more and more priests, nuns and followers. Buddhist sutra texts, images and other religious paraphernalia flooded the cities from abroad.”

Shintoism Hangs On Despite Buddhism’s Rise

Kawagoe wrote: “All the temple-building activity notwithstanding, even as Buddhism spread through Japan the deepest and most widespread religious activity of this period through the Nara period, remained kami worship, not Buddha worship. The most popular Buddhist movement of the period – ascetic mountain Buddhism — was associated with mountains where particular kami were believed to reside. Buddhist ritual was regarded as similar to kami worship since both emphasised divine blessings that could be obtained here and now. Buddhist worship spread to local communities, helped by the building of Buddhist temples by clan chiefs who continued to function as chief priests in the worship of clan kami. Shrines and temples came to be regarded as compatible, some shrines called jinguji had their own temples, while other Buddhist temples were guarded by certain kami. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Eventually due to the close connection between kami worship and spread of Buddhism, local doctrines developed involving ideas such as a particular kami and Buddha existing as one body (shinbutsu dotai) and a kami manifesting the essence of Buddha (honji suijaku). The interaction between kami worship and Buddhist doctrine is referred to as kami-Buddha fusion (shinbutsu shugo).

Japanese kami (gods) withe their Buddhist equivalent

Honji-Suijaku: Merging of Shinto and Buddhism

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: From China, Buddhism spread to Korea and then Japan. By the time Buddhism got to Japan, it was approximately 1000 years old and had changed much since the days of its founder. Although, as we have seen, Buddhism encountered some resistance when it first arrived in Japan, this resistance was not rooted in deep-seated cultural biases as was the case with Buddhism in China. Buddhism merged with native Japanese forms of religion in an almost seamless web. The basic formula was that native Japanese deities were local manifestations of Buddhas or lesser Buddhist deities. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“As we have seen, the appeal of Buddhism to Japanese in the sixth century was as a superior, more powerful form of magic than native shamanism. As Buddhism spread during the Asuka period and later, it permanently altered native religious traditions. Under Buddhist influence, for example, women no longer played a major role in religious life (at least in the major urban areas--the situation in the countryside may have been different), even in native religious rites at shrines. Buddhism also began to absorb elements of Japan’s native religions into itself. Native kami, for example became protectors of Buddhist temples in their area, and many Buddhist temples contained shrines to these kami within their compounds. It was only after Buddhism became established that scribes recorded native Japanese prayers and religious practices. Japanese documents purporting to describe Japan’s native religious practices before the coming of Buddhism were all written after the coming of Buddhism. We cannot always be sure, therefore, which elements in these documents were purely Japanese and which were Buddhist. Many were undoubtedly a mixture of the two religious traditions. ~

“By the Nara period, the process of combining native Japanese forms of religion with Buddhism was well underway. The idea developed that Japanese kami were local manifestations (suijaku, gongen, or keshin) of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. In such a relationship, the Buddhas or Bodhisattvas were known as honji, or "original ground". All major Japanese kami became formally linked with Buddhist counterparts. For example, the great solar Buddha, Vairocana, became linked with the Japanese solar deity Amaterasu. Specifically, Amaterasu came to be regarded as the local Japanese manifestation of the solar Buddha. In this way, Buddhism absorbed native Japanese religion, and the two became thoroughly interconnected. ~

“The proper technical term for this interconnection is honji-suijaku. The honji element was always a Buddhist deity in medieval times, and the suijaku was the local Japanese manifestation of that Buddhist deity. This local Japanese manifestation would also be a kami. Among other things, this formulation indicates the primacy of Buddhism at least in formal religious circles during medieval times. As we move closer to modern times, some Japanese began to re-formulate honji-suijaku, with native deities on a par with, or even superior to their Buddhist counterparts. But such a re-formulation never attained much influence until the 1860s and 70s. ~

Kami in Buddhist clothing

“We have seen that religion was a major part of the politics and symbolism of imperial rule following the Taika Reforms. The religion of the emperor and his or her court was a mixture of Buddhist and native elements. A large portion of the emperor’s time and energy was taken up with religious rites. As the political power of the emperors grew after 645, what was once the religion of one particular uji (albeit a particularly prominent one) gradually became the official religion of the new Japanese state. The emperors established a large shrine at Ise, in the Yamato area, to house the spirit of Amaterasu. This shrine became an important symbol of the imperial family. In modern times, it became an important symbol of Japan as a nation. Traditionally, the shrine buildings were torn down and rebuilt every twenty years. ~

The following is the text of an official "grain-petitioning" prayer said during the second month at the Ise shrine:

By the solemn command of the Emperor,

I humbly speak before you,

Great Sovereign Deity, whose praises are fulfilled

In the bed-rock below

On the upper reaches of the Isuzu river

At Uji in Watarai:

I humbly speak this solemn command

To bring and present the great offerings

Habitually presented at the Grain-petitioning of the Second month. ~

Buddhism and Buddhist Art in Japan

According to the Asia Society Museum: “A major, long-established East Asian route of trade and influence ran from northern China down the Korean peninsula and across the Korea Strait to Japan. Traveling along this route, Mahayana Buddhism was introduced into Japan from Korea in the sixth century (traditionally, in either 538 or 552), as part of a diplomatic mission that included gifts such as an image of Shakyamuni Buddha and several volumes of Buddhist texts. As in Korea, the religion had a lasting effect on the native culture; today, Buddhism is the dominant religion in Japan. As Buddhism prospered there, related arts also flourished. By the seventh century, when the religion was firmly established, Japan had dozens of temple complexes, various orders of priests and nuns, and a body of skilled artisans to craft the icons and other accoutrements of faith needed.[Source: Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org |~| ]

Horyuji Buddha

“During the eighth century (Nara period, 710 – 94), Japan was part of an international trading network that linked it with such distant countries as India and Iran, although the strongest cultural and artistic influences still came from China and Korea. Japan's cosmopolitan nature at this time is illustrated by the eye-opening ceremony in 752 of a large bronze image of Roshana (Mahavairocana), the supreme Buddha. The statue was housed in the main hall of Todai-ji in Nara. The hall was built for the statue and is still the world's largest wooden structure, the Buddha's eyes were painted in by an Indian monk, an event that was witnessed by roughly ten thousand priests and numerous foreign visitors. |~|

“Vajrayana (Esoteric) Buddhism, and its attendant pantheon of deities, was introduced to Japan in the Early Heian Period (794 – 894) by a number of Japanese priests. They studied the religion in China and returned home to found influential monasteries, two of which became the centers of the two main Japanese Buddhist sects, Tendai and Shingon. Images of wrathful deities, such as Fudo Myo-o ("Immovable Wisdom King"), were introduced at this time as part of the Vajrayana Buddhist pantheon. Fudo Myo-o's dark skin, fierce expression, fangs, and bulging eyes indicate his power to vanquish all demons. |~|

“In the Late Heian Period (894 – 1185) and in the following centuries, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. The salvationist Pure Land Buddhism taught that faith in Amida, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and the diligent recitation of his name enabled the soul to be reborn in a heavenly Pure Land rather than in a Buddhist hell or other undesirable rebirth. Intense devotion to Amida produced voluminous requests for Buddhist statuary and painting in addition to the many temples dedicated to him. Another salvationist deity popular at this time was Jizo, who had been introduced to Japan centuries earlier as a bodhisattva in the Mahayana Buddhist pantheon. Jizo is a deity of compassion and benvolence whose powers expanded as time passed. By the time of the Kamakura period (1185 – 1333), Jizo had the guise of an itinerant monk who gave succor to children, mothers, and travelers. It was during the Kamakura period that Buddhism became the faith of all people of all classes. This was due, in part, to the many priests who became itinerant evangelists and brought Pure Land Buddhism to the masses. |~|

“Even with its formidable physical barriers, the Himalayan region was never completely isolated from the rest of the world. Through high passes and steep, narrow pathways many cultural migrations have taken place, and trade routes, established in prehistory, have coursed with Tibetan products such as musk, wool, yak tails, and salt sold south to India, and gold, spices, perfumes, and precious textiles sent northward. Later, foundational Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism, and Vajrayana Buddhism traveled along these same roads, and monasteries built near them offered food and shelter in addition to spiritual succor to those passing through, who, in turn, kept the monasteries' coffers full. Pilgrims, monks, and missionaries usually traveled with merchant caravans for safety, although at some points they could take shorter, more dangerous routes that were too difficult for heavily loaded animals. Buddhist travelers often carried portable shrines with them and either brought from home or purchased en route paintings, bronzes, manuscripts, or votive plaques. These devotional goods of pious merchants, pilgrims, and monks played a part in the wide dispersion of Buddhist art styles and iconography, as did the mobility of artists, who also traveled along the trade routes to patrons in distant monasteries or cities. |~|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Asuka Musuem and Asuka tourist information

Text Sources: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016