GOVERNMENT OF INDONESIA

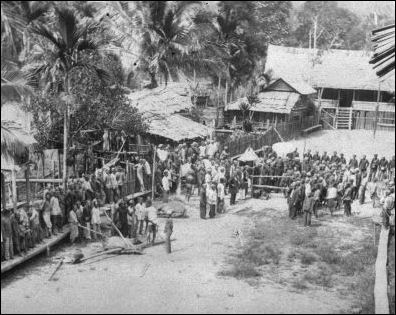

village meeting in Indonesia Indonesia is the world’s third largest democracy after India and the United States. It is a republic based on separation of powers among executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The constitution of 1945 is in force but was amended in 1999–2002. The government is somewhat similar to that of Turkey in that it is a Muslim secular democracy with a strong military.

The 1945 constitution was amended in 1999–2002 to make the once powerful, party-centered presidency subject to popular election and limited to two five-year terms. The president and vice president are elected on single ticket, usually representing a coalition of parties. Winning tickets must gain more than 60 percent of popular vote in the first round of voting and at least 20 percent of vote in half of provinces. If percentages not met, second-round runoff election held. The President is both the chief of state and head of government. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Legislative power vested in People’s Representative Council (DPR) and less-powerful upper house, Regional Representative Council (DPD). People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), which formerly elected the president and vice president, now joint sitting of the DPR and DPD but retains separate powers restricted to swearing in president and vice president, amending constitution, and having final say in impeachment process. Newly decentralized power of subnational authorities enshrined and delineated in amended constitution. Numerous political parties; Democrat Party (PD), Partai Golkar (Golkar Party), and Indonesian Democracy Party–Struggle (PDI–P) gained largest number of DPR seats in 2009 election. *

Capital: Jakarta Date of Independence: Proclaimed August 17, 1945, from the Netherlands. The Hague recognized Indonesian sovereignty on December 27, 1949. The Constitution was drafted July to August 1945, and became effective on August 17, 1945. It was abrogated by 1949 and 1950 constitutions. The 1945 constitution was restored July 5, 1959. It has been amended several times, last in 2002. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

Indonesia’s moto is: "One country. One people. One language." There is a fear that too much diversity could splinter Indonesia like the former Soviet Union or the Balkans. At the same time the Javanese pull most of the political strings. Seth Mydans wrote in the New York Times, "Indonesian rule has sometimes been likened to a colonial structure, with the dominant Javanese on their relatively small island asserting their rule over the larger and more resource-rich outer islands."

Names for Indonesia

Formal Name: Republic of Indonesia (Republik Indonesia). The the word Indonesia was coined from the Greek “indos”—for India—and “nesos”— for island). Short Form: Indonesia. Term for Citizen(s): Indonesian(s). Former Names: Netherlands East Indies; Dutch East Indies.

The term Indonesia was invented by James Richardson Loga in his study “The Languages and Ethnology of the Indian Archipelago” (1857). The name Indonesia was favored by anthropologists because it was similar to names given to neighboring cultural areas such as Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia.

Indonesia used to called the Dutch East Indies and before that the East Indies and the Malay Archipelago. The term East Indies was first used to describe present-day India, Southeast Asia and Indonesia after Columbus called the islands on the Caribbean the West Indies.

The name “Indonesia” was officially adopted after Indonesia became independent in 1945 in part because it previous name, the Dutch East Indies, wouldn’t do. Indonesia can mean either “extended India” or “the islands of India.”

Flag, Symbols and Slogans

Flag: two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white. The colors are derived from the banner of the Majapahit Empire of the 13th-15th centuries; red symbolizes courage, white represents purity. Adopted in 1945, it was first used by the Indonesian National Movement in the 1920s. The Indonesian flag is similar to the flag of Monaco, which is shorter. It is also similar to the flag of Poland, which is white (top) and red.

National symbols: garuda (mythical bird). National anthem: "Indonesia Raya" (Great Indonesia) with lyrics and music by Wage Rudolf (W.R.) Supratman (1903-38). It was first performed in 1928 and adopted as the national anthem in 1945.

The national coat of arms of Indonesia depicts the Garuda—an ancient mythical bird—which symbolizes creative energy, the greatness of the nation, and nature. The 8 feathers on the tail, 17 on each wing, and 45 on the neck stand for the date of Indonesia’s independence (August 17, 1945). The shield symbolizes self- defense and protection in struggle. The five symbols on the shield represent the state philosophy of Pancasila. The motto “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” (“Unity in Diversity”) on the banner signifies the unity of the Indonesian people despite their diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. After independence, the slogan “Unity in Diversity” was pushed on Indonesians.

Evolution of Proper Democracy in Indonesia

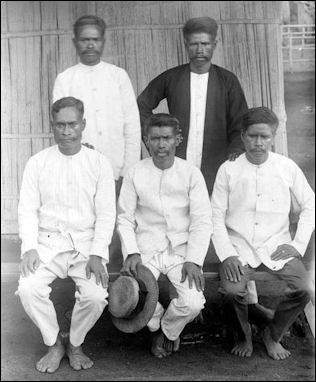

Headmen in the Moluccas

President Suharto resigned in 1998, and Indonesia began a transition to democracy, a process that has had the country struggling to establish a new political identity. This struggle has taken place on four fronts: executive–legislative relations, center–region relations, religion–state relations, and interethnic relations. A slow but eventually successful process of constitutional reforms from 1999 to 2002 addressed the first three fronts. Political elites in the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR; for this and other acronyms, see table A) established a strongly presidential system with directly elected national and local chief executives, stronger legislatures, and an independent judiciary, as well as a decentralized political system with significant local autonomy. They also maintained Indonesia’s identity as a plural, tolerant, and moderate Muslim- majority society with significant non-Muslim minorities, but not an Islamic state. [Source: Library of Congress *]

This vision was sorely tested by the passage in some districts of local regulations implementing parts of Islamic law—sharia, or syariah in Bahasa Indonesia —and by the Al Qaeda–linked terrorist attacks in Bali and Jakarta from 2002 to 2009. Indonesian citizens heartily endorsed these changes through their broad, enthusiastic, and largely nonviolent participation in the 1999, 2004, and 2009 electoral processes. The constitutional reform process indicated little on the fourth front, interethnic relations, except that Indonesia was still to be a state based on Pancasila, the five-point pan-religious, pan-ethnic state ideology created by the first president, Sukarno (in office 1945–67). Indonesians have struggled to overcome deadly communal strife in Maluku, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan, among other places, but by 2009 much of this violence had receded. *

Consolidation of the new democracy remains a significant challenge. By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, reforms in the national-security sector were only partial at best. The military and police remained neutral in elections between 1999 and 2009, and they were stripped of their appointed seats in legislatures at all levels. The system of secondment of military officers to the civilian bureaucracy was also abolished. However, the roots of the military’s political influence—the territorial system, business ventures, and the lack of democratic civilian oversight—only began to be addressed under the leadership of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who took office in 2004. The police were organizationally separated from the military in 1999 and have done a respectable job of addressing the threat of terrorism, but for most Indonesian citizens, daily interactions with the police have not been reformed: overall, corruption and ineffectiveness remain widespread.

The implementation of decentralization, including revised autonomy laws passed in 2004 and the direct election of regional chief executives (governors, mayors, and district administrative heads or regents— bupatis) beginning in 2005, created its own problems, as corruption also has been decentralized, and the national government is confronted with a host of local regulations that are inconsistent with national laws and the constitution. Executive– legislative relations are frequently contentious, as the president and the legislative branch establish a working relationship within the new constitutional parameters and the legislature itself adjusts to the presence of a new upper house, the Regional Representative Council (DPD), established in 2004. Internal reform of these entities, to unclog the process of enacting laws and strengthen institutional capacity, is a pressing need. *

The new political system has made dealing with these pressing issues more complex than previously. Legislatures are more independent of the executive branch, and there are now two legislative bodies at the national level. Provincial and district governments are more powerful and have greater autonomy vis-à-vis the central government.

Democracy in Indonesia

In the last 20 years, Indonesia has grown to become the world’s third-largest democracy and the economy has developed to become a middle-income country. Indonesia is the world's third largest democracy after India and the United States. One Western diplomat told the New York Times in the early 2000s that the Indonesian government was “almost hydroponic”—like a floating structure with danging, ineffectual roots

Democracy has been inhibited but is largely unrestricted. The press is relatively free. Elections come off with few hitches. Small groups of protesters calling for things like land reform, action on air pollution and the promotion of breast feeding gather outside the Parliament on an almost daily basis. William Pesek of Bloomberg News wrote, “What looks messy on CNN is really the workings of democracy and free expression taking hold—with all the risks that come with them.”

Democracy functions relatively well know but some had their doubts after Suharto was ousted. At that time many Indonesians grew weary of the economic chaos, upheaval, ethnic violence, terrorism and uncertainty that the shift to democracy was accompanied by. Stability and security remain important issues today. Some still look back on Suharto era, with its relative security and stability, with fondness and nostalgia while others see the occasional turbulence and problems as growing pains and phases that Indonesia is going through on the road to mature democracy.

In 2012, The Economist reported: “ A survey conducted last year, for example, found that Suharto’s authoritarian “New Order” was seen as preferable to politics in the reform era. Some national politicians certainly seem to be losing patience with local democracy: Mr Yudhoyono’s government is proposing revisions to a regional governance law that would replace direct elections for governors with indirect elections by local legislatures. This would in effect transfer power from ordinary voters to political parties.” [Source: The Economist, September 6, 2012 /*]

See Politics

Inability of Indonesia’s Democracy to Deal with Hard Issues

After the government of President Yudhoyono suffered a heavy political defeat when its plan to raise fuel prices was rejected by a vote in the House of Representatives and under pressure from massive street protests, Endy Bayuni wrote in Foreign Policy, “Indonesia may claim to have a functioning democracy; an open debate with wide public participation over an issue as important as fuel prices is certainly one positive indicator. But there are also grounds for arguing that Indonesia is now veering towards a dysfunctional democracy, one where populism and the rule of the majority have increasingly overpowered rational and moral arguments for more responsible government. [Source: Endy Bayuni, Foreign Policy, April 11, 2012 |+|]

“The will of the people has prevailed in guaranteeing that the price of gasoline in Indonesia — at the equivalent of 50 cents per liter — remains among the lowest in the world. Indonesia's "noisy democracy" went up by several decibels in the weeks before April 1, the day fuel prices were due to increase by 33 percent. No political cause is more popular in Indonesia than cheap gas: Almost everyone (except perhaps those who have to balance the books at the end of the day) embraces it. The outcome of this debate — in the House of Representatives, in TV talk-show programs, in cafes, in offices and in the streets — was inevitable, if not predictable: They who advocate cheap oil win. |+|

“The government, whose job is to balance the budget or find the money to pay for the heavy cost of subsidizing domestic fuel consumption, is almost alone. Lost in the noisy debate was their argument that the energy subsidy bill for 2012, at 225.35 trillion rupiah ($25 billion), was already eating up 15 percent of state spending. That's a huge sum, one that could be better spent on more important social and economic programs, such as poverty eradication, schooling, health care for the poor, or the construction of economic infrastructure. The other argument — that the gasoline subsidy is enjoyed mostly by the wealthy rather than the poor — was also lost in the debate. |+|

“Indonesia may have been rich in oil once, but the new millennium saw rising domestic consumption and rapidly falling reserves, turning the country from an oil exporter to a net importer. Old habits (and paradigms) die hard: Indonesia only quit the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 2008. Judging by the recent national debate about fuel prices, it appears that most people still believe, or would like to believe, that Indonesia is still flush with oil. |+|

“Cheap oil unfortunately also means cheap politics. What those advocating for cheap oil are not saying, out of ignorance or self-interest, is that someone, somewhere, will have to pay for that (costly) fuel subsidy. The pro-cheap oil side may have prevailed, but the government of President Yudhoyono is not the ultimate loser in this game. The biggest losers are the people and the taxpayers — in other words, the entire nation. The very same people the advocates for cheap oil claim to speak for will have to pay the price, either through taxes or the potential loss of services such as education and healthcare. |+|

“More troubling for Indonesia's nascent democracy is the message sent with this government defeat: If you can't win your case through a civil debate in the House, mobilize the people in the streets to wage your fight for you. And don't forget to make ample use of the catchphrase "on behalf of the people." What we saw in the streets just now was not so much "people power" as it was "mob power." Indonesians will have to brace themselves for an even noisier democracy in the coming years.” |+|

Indonesian Democracy: an Example to Other Muslim Nations?

Of the 47 Muslim majority nations worldwide, only about a third are electoral democracies. The situation in the Arab world is far worse. Of the 16 Arab Muslim countries, none had electoral democracies before the Arab Spring protests on the early 2010s, now a handful do but monarchies and authoritarian regimes are still the rule. In contrast, more than 80 percent of the world's 191 countries are considered democratic to varying degrees.

After voting took place in the 2004 election, Peter Brookes of the Heritage Foundation wrote: “ Lo and behold, the world's largest Muslim nation, Indonesia, went to the polls on to elect a president for the first time in — what appears to be from initial reports — a free and fair democratic election. Just six years after throwing off the 32-year yoke of Indonesian strongman Suharto, Indonesia has gone from autocracy to democracy, a remarkable — and highly unanticipated — political transformation. It might sound flippant, but in some ways, it doesn't matter who wins the Indonesian presidency. The mere fact that this giant Southeast Asian nation of 240 million people (87 percent Muslim) is voting in a democratic election is a major victory for freedom — and, more importantly, the Muslim world.After today, no one can say that Muslims can't be political pluralists. In fact, some Islamic scholars have long argued that the Koranic principle of shura (consultation) was the Prophet Mohammed's endorsement of democratic ideals. [Source: Peter Brookes, September 21, 2004 ]

“Others in the Muslim anti-democracy camp will say that Indonesian Islam, which came to the vast 17,000-island archipelago via India, is different than the brand of Islam practiced by Middle Eastern Muslims. True: Islam, like other religions, isn't monolithic. But this misses the point. Indonesia, a Muslim nation, proves empirically that Islam — based on the very same Koran — can be secular, tolerant and democratic. To their credit, insightful Indonesian Islamic activists and intellectuals sought — and found — democratic values within the teachings of Islam. By doing so, the success of the Indonesian democratic revolution dispels the long-held myth that democracy and Islam cannot thrive together.

“Heavy-handed, autocratic Muslim rulers have also justified their tight grip on the political reins because of the threat of terrorism. But that argument is contradicted by Indonesian fact. Yes, Indonesia has a terrorism problem. It's the home of al Qaeda's Southeast Asian franchise, Jemaah Islamiya — perhaps Osama bin Laden's largest terrorist spin-off. Jemaah Islamiya is responsible for the infamous October 2002 Bali nightclub bombing, which killed more than 200. But did Indonesia roll back political freedoms to the repressive Suharto days after the terrorist attacks? No. Using the rule of law, it cracked down on terrorists (arresting more than 100 and convicting more than 70) and pressed forward with successful, democratic national parliamentary and presidential elections.”

“Fortunately, Indonesia has recognized what others in the Muslim world haven't: freedom, democracy and open markets are strong antidotes to radicalism and terrorism. By increasing economic opportunity, giving people a stake in the political process and improving the quality of life, these principles of liberty undermine the attraction of militancy, hatred and violence. Political freedom is a universal value and the right of all mankind — including the world's 1.3 billion Muslims.No, Indonesia's democracy isn't perfect — but it's flourishing. And if democratic ideals can flourish here, they can prosper anywhere in the Islamic world.”

Pancasila

Pancasila is a state ideology that appeared under Sukarno in 1945 around the same time he declared Indonesia’s independence and was pushed heavily during the Suharto years from the mid 1960s to the late 1990s. One of the primary goals of these two leaders was to create a national philosophy that would bind Indonesians together and prevent the country from fragmenting along regional, religious and ethnic lines.

Pancasila has been incorporated into the national coat of arm, which appears everywhere: on textbooks, in government offices, at police stations. Under Suharto it was regarded as so important that anyone who questioned it was in political hot water. Accusing someone of criticizing it is an effective way to discredit them.

The Five Pillars (“Pancasila”), and their symbols in the Indonesian coat of arms, are beliefs in: 1) one and only supreme god (symbolized by a star); 2) a just and civilized humanity (a chain); 3) the unity of Indonesia (banyan tree); 4) democracy is guided by inner wisdom of deliberation of representatives (buffalo head); and 5) social justice for all citizens of Indonesia (sprays of rice and cotton).

Some of the wording is deliberately vague and can be used both to support both democracy and autocracy. According to Pancasila any group that asserted itself to strongly was crushed and people could worship any of the major religions but were not allowed to be atheists. The first principal was attempt to come up an understanding that would include all major religions: Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Hinduism. Many Islamists saw it as a declaration for an Islamic state.

History of Pancasila

The government undertook at independence the major effort of subsuming all of Indonesia’s political cultures, with their different and often incompatible criteria for legitimacy, into a national political culture based on the values set forth in the Pancasila. The preamble of the 1945 constitution establishes the Pancasila as the embodiment of basic principles of an independent Indonesian state. These five principles were announced by Sukarno in a speech on June 1, 1945. In brief, and in the order given in the constitution, the Pancasila principles are belief in one supreme God, humanitarianism, nationalism expressed in the unity of Indonesia, representative democracy, and social justice. Sukarno’s statement of the Pancasila, while simple in form, resulted from a complex and sophisticated appreciation of the ideological needs of the new nation. In contrast to Muslim nationalists who insisted on an Islamic identity for the new state, the framers of the Pancasila insisted on a culturally neutral identity, compatible with democratic or Marxist ideologies, and overarching the vast cultural differences of the heterogeneous population. Like the national language, Bahasa Indonesia, which Sukarno also promoted, the Pancasila did not come from any particular ethnic group and was intended to define the basic values for a national political culture. [Library of Congress *]

The Pancasila has its modern aspects, although Sukarno presented it in terms of a traditional Indonesian society in which the nation parallels an idealized village: society is egalitarian, the economy is organized on the basis of mutual cooperation (gotong royong), and decision making is by deliberation (musyawarah) leading to consensus (mufakat). In Sukarno’s version of the Pancasila—further defined by Suharto—political and social dissidence constituted deviant behavior. *

One reason why both Sukarno and Suharto were successful in using the Pancasila to support their authority, despite their very different policy orientations, is the generalized nature of the principles of the Pancasila. The Pancasila has been less successful as a unifying concept when leadership has tried to give it policy content. Suharto greatly expanded a national indoctrination program established by Sukarno to inculcate a regime-justifying interpretation of the Pancasila in all citizens, especially schoolchildren and civil servants. The Pancasila was thus transformed from an abstract statement of national goals into an instrument of social and political control. To oppose the government was to oppose the Pancasila. To oppose the Pancasila was to oppose the foundation of the state. The effort to enforce conformity to the government’s interpretation of Pancasila ideological correctness was not without controversy. The issue that persistently tested the limits of the government’s tolerance of alternative or even competitive systems of political thought was the position of religion, especially Islam. *

The democratic transition has entirely dismantled the New Order structures that institutionalized politicization of the Pancasila. Although the Pancasila is still taught in schools, the national indoctrination program for adults and the agency charged with managing it have both been abolished. Most importantly, political parties and social organizations are no longer required to adopt the Pancasila as their underlying ideological principle (asas tunggal). Prominent Muslim organizations in particular immediately took advantage of this change. For instance, the Development Unity Party (PPP) reestablished Islam as its ideological basis and returned to its pre-1984 party symbol, the Kaaba in Mecca. Secular nationalist parties and organizations, however, have retained the Pancasila as their ideological basis. In the early twenty-first century, the Pancasila thus remains alive in Indonesian political discourse in two ways. Harkening back to the pattern in the 1940s and early 1950s, it is one among several ideological strands underpinning political conflicts that have many other dimensions as well: economic, social, regional, and ethnic. On occasion, however, it is still used as a unifying force that can tie all Indonesians together within a national political culture. For example, President Yudhoyono has made several major speeches extolling the Pancasila’s virtues in this regard. While generally still aimed at countering the influence of Islamist discourse, this latter usage elevates the Pancasila above the fray of mundane political squabbles. *

Pancasila and Islam in Indonesia

Islam and the Indonesian state had a tense political relationship from the very outset of independence. The Pancasila’s promotion of monotheism is a religiously neutral and tolerant statement that equates Islam with the other religious systems: Christianity, Buddhism, and Hindu-Balinese beliefs. However, Muslim political forces had felt betrayed since signing the June 1945 Jakarta Charter, under which they accepted a pluralist republic in return for agreement that the state would be based upon belief in one God “with Muslims obligated to follow the sharia.” The decision two months later to remove this seven-word phrase from the preamble of the 1945 constitution, to keep predominantly Christian areas of eastern Indonesia from breaking away from the nationalist movement and declaring their own independence, set the agenda for future Islamic politics. At the extreme were the Darul Islam rebellions of the 1950s, which sought to establish a Muslim theocracy. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Orthodox Muslim groups saw the New Order’s emphasis on the Pancasila as an effort to subordinate Islam to a secular state ideology, even a “civil religion” manipulated by a regime inherently biased against the full expression of Muslim life. By the 1980s, however, within the legal and politically acceptable boundaries of Muslim involvement, the state had become a major promoter of Islamic institutions. The government even subsidized numerous Muslim community activities. Within the overall value structure of the Pancasila, Islamic moral teaching and personal codes of conduct balanced the materialism inherent in secular economic development. By wooing Islamic leaders and teachers, the state won broad support for its developmental policies. There is no question but that Islam was a state- favored religion in Indonesia, but it was not a state religion. That reality defined the most critical political issue for many orthodox Muslims. The so-called “hard” dakwah, departing from sermons and texts tightly confined to matters of faith and Islamic law, was uncompromisingly antigovernment. The Islamists called for people to die as martyrs in a “struggle until Islam rules.” This call, for the government, was incitement to “extremism of the right,” subversion, and terrorism. The government reaction to radical Islamic provocations was unyielding: arrest and jail.

Indonesia Eyes New Capital as Jakarta Bursts at Seams

Because Indonesia's capital, Jakarta is burst at the seams with over 10 million, is situated in set in an earthquake zone, suffers from frequent and is crippled by horrendous traffic inadequate infrastructure, some have floating the idea of establishing a new capital elsewhere in Indonesia.

Sara Webb of Reuters wrote: “A mere pinprick on the map of Java, Jonggol's cluster of tiny red-roofed houses set among banana groves and shimmering waterlogged rice fields may in years to come be destined for greater things. Now Jonggol is one of several sites being considered as a new administrative seat in a bid to relieve Jakarta's congestion, but at a potential cost of billions of dollars. This sudden thrust into the limelight appeals to some local residents in Jonggol, where few buildings exceed one storey and the nearest thing to a skyscraper is four floors high. "Now you can call this a village. I hope they will transform it into a city," said local resident Annur. "I don't mind if this becomes the capital, it would be more lively and beautiful."[Source: Sara Webb, Reuters, August 26, 2010]

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono has floated the idea of moving part of the capital in recent months, and earlier this month proposed increasing infrastructure spending, with plans to build 14 new airports as well as roads and railways, to lure foreign investment and boost growth. "The government takes this idea seriously," Velix Wanggai, an advisor to Yudhoyono, told Reuters. "The president considers it normal to look at moving the capital because of Jakarta's urban problems, the risk of disaster, and heavy environmental toll."

A new capital could — as was the case with Brasilia, studded with Oscar Niemeyers' architecture — be an emblem of national coming-of-age with careful urban planning and new infrastructure. "Anything that would lessen the congestion in Jakarta would be a blessing, so separating the business capital from the center of government could be a positive," said Tim Condon, regional economist for ING. "But it's also a huge investment. These moves are typically driven by political rather than economic considerations, the desire to develop an alternative part of the country. Is it really going to pay off in terms of increased efficiency by decongesting Jakarta?"

The choice of location can also lead to questions over government policy, and spur regional jealousies in a country composed of many different ethnic groups and religions. Of Indonesia's 17,000-odd islands it is Java, the cultural heart and home to 58 percent of Indonesians, which still calls the shots, making it the more likely site. "Java runs the country," said Condon, so a capital outside Java "would be pretty radical."

Malang in East Java, and Palangkaraya and Jayapura, which are outside Java, are also being considered, said Wanggai. Palangkaraya, on the island of Borneo, was former President Sukarno's choice for the capital because of its position in a quake-free region at the very center of the archipelago. A less likely site is Jayapura, at the easternmost extreme of Indonesia in resource-rich Papua, where the military has struggled to contain a decades-long secessionist movement. Despite its mineral, timber and energy reserves, Papua remains one of the poorest parts of the country. Building a new capital there would bring jobs and infrastructure, as well as an influx of Javanese and other ethnic groups, potentially diluting the Papuan majority and sowing further discontent.

The cost of such grandiose mega-projects can easily run into billions of taxpayer dollars, providing opportunities for patronage and land speculation. "I think there are no successful examples. I don't think it's wise to take that direction," Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, head of Yudhoyono's presidential delivery unit, told Reuters. Astana, Kazakhstan's showcase new capital boasting Norman Foster's architecture, cost over $12 billion.Malaysia's Putrajaya, the administrative capital built 25 km south of Kuala Lumpur, was promoted and pushed through by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad at an official cost of 11.83 billion ringgit ($3.77 billion). "I don't see any strong benefits" for Indonesia, said Song Seng Wun, regional economist at CIMB Research. "Maybe a few civil servants get a nice new aircon office and nice scenery but for the man in the street who is trying to find work in a textile company it's about whether the government's policies can lift the wages of the ordinary people."

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated June 2015