YOGA IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURIES

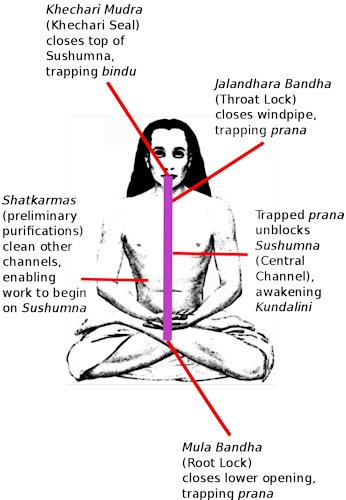

mode of action of Mudras and Bandhas on the Sushumna, leading to liberation in Hatha Yoga philosophy (the subtle fluids affected have numerous names including prana, bindu, and amrit)

Hatha yoga became a practiced exercise in the United States in the 1930s and 40s, and gained momentum in the 1960s, reached its peak in the 70s, when New Age idealism emerged in post 60s era and interest in Eastern spirituality was high among young Americans. A number of Indian yoga teachers came to the West to teach. In the 1980s, when a number of studies reported the health benefits of yoga, yoga was promoted as an exercise with its physical benefits taking precedence over its spiritual and mental ones. [Source: Lecia Bushak, Medical Daily, October 21, 2015]

David Gordon White wrote: “In the course of the past thirty years, yoga has been transformed more than at any time since the advent of hatha yoga in the tenth to eleventh centuries (Syman 2010). The theoretical pairing of yoga with mind-expanding drugs, the practice of “cakra adjustment,” the use of crystals: these are but a few of the entirely original improvisations on a four-thousand-year-old theme, which have been invented outside of India during the past decades. Aware of this appropriation of what it rightly considers to be its own cultural legacy, Indians have begun to take steps to safeguard their yoga traditions. In 2001, the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) was founded in India as a tool for preventing foreign entrepreneurs from appropriating and patenting Indian traditions as their own intellectual properties. Spurred by the 2004 granting of a U.S. patent on a sequence of twenty-six āsanas to the Indian- American yoga celebrity Bikram Chaudhury, the TKDL has turned its attention to yoga. In the light of the history outlined in this introduction, the TKDL has a vast range of theories and practices to protect. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

The number of people practicing yoga increased from 4 million in 2001 to 20 million in 2011. Scientific studies have linked yoga to the reduction of high blood pressure, depression, chronic pain, and anxiety and say it improves cardiac function, muscle strength, and circulation. Today, yoga is widely seen in the West as something you do in exercise class or take at the gym to build up your muscles and reduce stress you. In December 2014. The United Nations General Assembly named June 21 International Yoga Day, an annual celebration to incorporate yoga and meditation more into humanity all over the world.

Websites and Resources: Yoga National Institutes of Health, US government, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Yoga: Its Origin, History and Development, Indian government mea.gov.in/in-focus-article ; Different Types of Yoga - Yoga Journal yogajournal.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga Wikipedia ; Medical News Today medicalnewstoday.com ; Yoga and modern philosophy, Mircea Eliade crossasia-repository.ub.uni-heidelberg.de ; India's 10 most renowned yoga gurus rediff.com ; Wikipedia article on yoga philosophy Wikipedia ; Yoga Poses Handbook mymission.lamission.edu ; George Feuerstein, Yoga and Meditation (Dhyana) santosha.com/moksha/meditation

Vivekananda, the Founder of Modern Yoga

In the mid-19th century became intrigued with Indian culture in part because of the work by Theosophical Society. Yoga came to the attention of Westerners primarily through the efforts of Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu monk who toured Europe and the U.S. in the 1890s to spread knowledge about Hinduism among intellectuals. Vivekananda did much to bring attention to the Yoga Sutras, attributed to Patanjali and written sometime around A.D. 400, described what he believed were the main yoga traditions of his time. The Yoga Sutras focused mainly on removing all excess thought from the mind and focusing on a singular thing; but they were later incorporated more heavily than any other ancient yoga writings in modern, “corporate” yoga. [Source: Lecia Bushak, Medical Daily, October 21, 2015]

Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times, ““In the New York Times a few years back, Ann Louise Bardach wrote, wryly, that “you might blame Vivekananda” — a turn-of-the-century Hindu reformer, emissary to the United States and Indian nationalist who created a system of modern yoga called raja yoga — “for having introduced ‘yoga’ into the national conversation.” It’s a view echoed recently by the New Indian Express, which described him as “The Father of Yoga in the West.” The swami is known for a well-received speech he gave in Chicago in 1893 to the Parliament of the World’s Religions, in which he declared that “sectarianism, bigotry and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have long possessed this beautiful earth” and “had it not been for these horrible demons, human society would be far more advanced than it is now.” But the speech, in fact, never mentioned yoga. [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, February 7, 2013 ++]

Vivekananda in 1893

“In terms of his yogic teachings, Vivekananda had several Indian, European and North American contemporaries whose work was equally influential in the development of some of yoga’s earliest modern forms. Nineteenth-century American social radical Ida C. Craddock, who defended belly dancing’s “much needed blend of sexuality and spirituality,” for example, created a yoga system for married couples looking to improve their sex lives. Sadly, she was subsequently imprisoned on charges of obscenity and, facing the threat of more prison time, took her own life. Another early modern yoga advocate was Paramahansa Yogananda, an Indian guru who traveled to the United States and taught yoga to Americans in the first half of the 20th century. He envisioned yoga as a scientific path to the experience of God and taught what he called kriya yoga at a time when such religious experimentation was unusual and discouraged. The organization he founded, the Self-Realization Fellowship, is still thriving. ++

“Vivekananda’s emphasis on self-control, meditation and psychology appealed to many who challenged institutionalized religion. He encouraged his disciples to turn inward, toward the self, rather than outward, toward external authorities. But he wasn’t a fan of yoga poses — and those, of course, are what most of us envision when we think of yoga.” ++

White wrote: “Vivekananda’s rehabilitation of what he termed “rāja yoga” is exemplary, for its motives, its influences, and its content. A shrewd culture broker seeking a way to turn his countrymen away from practices he termed “kitchen religion,” Vivekananda seized upon the symbolic power of yoga as a genuinely Indian, yet non-sectarian, type of applied philosophy that could be wielded as a “unifying sign of the Indian nation . . . not only for national consumption but for consumption by the entire world”. For Vivekananda, rāja yoga, or “classical yoga,” was the science of yoga taught in theYoga Sūtra, a notion he took from none other than the Theosophist Madame Blavatsky, who had a strong Indian following in the late nineteenth century. Following his success in introducing rāja yoga to western audiences at the 1892 World Parliament of Religions at Chicago, Vivekananda remained in the United States for much of the next decade (he died in 1902), lecturing and writing on theYoga Sutras. His quite idiosyncratic interpretations of this work were highly congenial to the religiosity of the period, which found expression in India mainly through the rationalist spirituality of Neo-Vedānta. So it was that Vivekananda defined rāja yoga as the supreme contemplative path to selfrealization, in which the self so realized was the supreme self, the absolute brahman or god-self within. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

“While Vivekananda’s influence on present-day understandings of yoga theory is incalculable, his disdain for the means and ends of hatha yoga practice were such that that form of yoga—the principal traditional source of modern postural yoga—was slow to be embraced by the modern world. It should be noted here that within India, the tradition of hatha yoga had been all but lost, and that it was not until the publication of a number of editions of late hatha yoga texts, by the Theosophical Society and others, that interest in it was rekindled.”

Development of Modern Yoga

White wrote: “In Calcutta, colonial India’s most important center of intellectual life, the late nineteenth century saw the emergence of a new “holy man” style among leaders of the Indian reform and independence movement. A prime catalyst for this shift was the 1882 publication of Bankim Chandra Chatterji’s powerful and controversial Bengali novel Ānandamath (Lipner 2005), which drew parallels between the Sannyasi and Fakir Rebellion and the cause of Indian independence. [Source: David Gordon White, “Yoga, Brief History of an Idea”]

“In the years and decades that followed, numerous (mainly Bengali) reformers shed their Western-style clothing to put on the saffron robes of Indian holy men. These included, most notably, Swami Vivekananda, the Indian founder of “modern yoga”; and Sri Aurobindo, who was jailed by the British for plotting a sannyāsī revolt against the Empire but who devoted the latter part of his life to yoga, founding his famous āśram in Pondicherry in 1926. While the other leading yoga gurus of the first half of the twentieth century had no reform or political agenda, they left their mark by carrying the gospel of modern yoga to the west. These include Paramahamsa Yogananda, the author of the perennial best-selling 1946 publication, Autobiography of a Yogi; Sivananda, who was for a short time the guru of the pioneering yoga scholar and historian of religions Mircea Eliade; Kuvalayananda, who focused on the modern scientific and medical benefits of yoga practice (Alter 2004: 73–108); Hariharananda Aranya, the founder of the Kapila Matha [Jacobsen]; and Krishnamacharya [Singleton, Narasimhan, and Jayashree], the guru of the three hatha yoga masters most responsible for popularizing postural yoga throughout the world in the late twentieth century.

History of Asanas

“Indeed, none other than the great Krishnamacharya himself went to Tibet in search of true practitioners of a tradition he considered lost in India (Kadetsky 2004: 76–79). One of the earliest American practitioners to study yoga under Indian teachers and later attempt to market the teachings of hatha yoga in the west, Theos Bernard died in Tibet in the 1930s while searching there for the yogic “grail”. Whatever Krishnamacharya found in his journey to Tibet, the yoga that he taught in his role of “yoga master” of the Mysore Palace was an eclectic amalgam of hatha yoga techniques, British military calisthenics, and the regional gymnastic and wrestling traditions of southwestern India (Sjoman 1996). Beginning in the 1950s, his three leading disciples—B. K. S. Iyengar, K. Pattabhi Jois, and T.K.V. Desikachar—would introduce their own variations on his techniques and so define the postural yoga that has swept Europe, the United States, and much of the rest of the world. The direct and indirect disciples of these three innovators form the vanguard of yoga teachers on the contemporary scene. The impact of these innovators of yoga, with their eclectic blend of training in postures with teachings from theYoga Sutras, also had the secondary effect of catalyzing a reform within the Śvetāmbara Jain community, opening the door to the emergence of a universalistic and missionary yoga-based Jainism in the United Kingdom in particular.

Krishnamacharya: The Inventor of Modern Posture-Centered Yoga

Fernando Pagés Ruiz wrote in Yoga Journal: “You may never have heard of him, but Tirumalai Krishnamacharya influenced or perhaps even invented your yoga. Whether you practice the dynamic series of Pattabhi Jois, the refined alignments of B.K.S. Iyengar, the classical postures of Indra Devi, or the customized vinyasa of Viniyoga, your practice stems from one source: a five-foot, two-inch Brahmin born more than one hundred years ago in a small South Indian village. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007]

“He never crossed an ocean, but Krishnamacharya's yoga has spread through Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Today it's difficult to find an asana tradition he hasn't influenced. Even if you learned from a yogi now outside the traditions associated with Krishnamacharya, there's a good chance your teacher trained in the Iyengar, Ashtanga, or Viniyoga lineages before developing another style. Rodney Yee, for instance, who appears in many popular videos, studied with Iyengar. Richard Hittleman, a well-known TV yogi of the 1970s, trained with Devi. Other teachers have borrowed from several Krishnamacharya-based styles, creating unique approaches such as Ganga White's White Lotus Yoga and Manny Finger's ISHTA Yoga. Most teachers, even from styles not directly linked to Krishnamacharya—Sivananda Yoga and Bikram Yoga, for example—have been influenced by some aspect of Krishnamacharya's teachings.

“Many of his contributions have been so thoroughly integrated into the fabric of yoga that their source has been forgotten. It's been said that he's responsible for the modern emphasis on Sirsasana (Headstand) and Sarvangasana (Shoulderstand). He was a pioneer in refining postures, sequencing them optimally, and ascribing therapeutic value to specific asanas. By combining pranayama and asana, he made the postures an integral part of meditation instead of just a step leading toward it.

Krishnamacharya at 100

“In fact, Krishnamacharya's influence can be seen most clearly in the emphasis on asana practice that's become the signature of yoga today. Probably no yogi before him developed the physical practices so deliberately. In the process, he transformed hatha—once an obscure backwater of yoga—into its central current. Yoga's resurgence in India owes a great deal to his countless lecture tours and demonstrations during the 1930s, and his four most famous disciples—Jois, Iyengar, Devi, and Krishnamacharya's son, T.K.V. Desikachar—played a huge role in popularizing yoga in the West.”

“Krishnamacharya remains a mystery, even to his family. He never wrote a full memoir or took credit for his many innovations....Krishnamacharya began his teaching career by perfecting a strict, idealized version of hatha yoga. Then, as the currents of history impelled him to adapt, he became one of yoga's great reformers. Some of his students remember him as an exacting, volatile teacher; B.K.S. Iyengar told me Krishnamacharya could have been a saint, were he not so ill-tempered and self-centered. Others recall a gentle mentor who cherished their individuality. Desikachar, for example, describes his father as a kind person who often placed his late guru's sandals on top of his own head in an act of humility.

Krishnamacharya’s Early Life

Fernando Pagés Ruiz wrote in Yoga Journal: “As a young man, Krishnamacharya immersed himself in this pursuit, learning many classical Indian disciplines, including Sanskrit, logic, ritual, law, and the basics of Indian medicine. In time, he would channel this broad background into the study of yoga, where he synthesized the wisdom of these traditions. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“According to biographical notes Krishnamacharya made near the end of his life, his father initiated him into yoga at age five, when he began to teach him Patanjali's sutras and told him that their family had descended from a revered ninth-century yogi, Nathamuni. Although his father died before Krishnamacharya reached puberty, he instilled in his son a general thirst for knowledge and a specific desire to study yoga. In another manuscript, Krishnamacharya wrote that "while still an urchin,”he learned 24 asanas from a swami of the Sringeri Math, the same temple that gave birth to Sivananda Yogananda's lineage. Then, at age 16, he made a pilgrimage to Nathamuni's shrine at Alvar Tirunagari, where he encountered his legendary forefather during an extraordinary vision.

“As Krishnamacharya always told the story, he found an old man at the temple's gate who pointed him toward a nearby mango grove. Krishnamacharya walked to the grove, where he collapsed, exhausted. When he got up, he noticed three yogis had gathered. His ancestor Nathamuni sat in the middle. Krishnamacharya prostrated himself and asked for instruction. For hours, Nathamuni sang verses to him from the Yogarahasya (The Essence of Yoga), a text lost more than one thousand years before. Krishnamacharya memorized and later transcribed these verses.

Krishnamacharya's Mysore school

“The seeds of many elements of Krishnamacharya's innovative teachings can be found in this text, which is available in an English translation (Yogarahasya, translated by T.K.V. Desikachar, Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, 1998). Though the tale of its authorship may seem fanciful, it points to an important trait in Krishnamacharya's personality: He never claimed originality. In his view, yoga belonged to God. All of his ideas, original or not, he attributed to ancient texts or to his guru.

“After his experience at Nathamuni's shrine, Krishnamacharya continued his exploration of a panoply of Indian classical disciplines, obtaining degrees in philology, logic, divinity, and music. He practiced yoga from rudiments he learned through texts and the occasional interview with a yogi, but he longed to study yoga more deeply, as his father had recommended. A university teacher saw Krishnamacharya practicing his asanas and advised him to seek out a master called Sri Ramamohan Brahmachari, one of the few remaining hatha yoga masters.

“We know little about Brahmachari except that he lived with his spouse and three children in a remote cave. By Krishnamacharya's account, he spent seven years with this teacher, memorizing the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, learning asanas and pranayama, and studying the therapeutic aspects of yoga. During his apprenticeship, Krishnamacharya claimed, he mastered 3,000 asanas and developed some of his most remarkable skills, such as stopping his pulse. In exchange for instruction, Brahmachari asked his loyal student to return to his homeland to teach yoga and establish a household.

“Krishnamacharya's education had prepared him for a position at any number of prestigious institutions, but he renounced this opportunity, choosing to honor his guru's parting request. Despite all his training, Krishnamacharya returned home to poverty. In the 1920s, teaching yoga wasn't profitable. Students were few, and Krishnamacharya was forced to take a job as a foreman at a coffee plantation. But on his days off, he traveled throughout the province giving lectures and yoga demonstrations. Krishnamacharya sought to popularize yoga by demonstrating the siddhis, the supranormal abilities of the yogic body. These demonstrations, designed to stimulate interest in a dying tradition, included suspending his pulse, stopping cars with his bare hands, performing difficult asanas, and lifting heavy objects with his teeth. To teach people about yoga, Krishnamacharya felt, he first had to get their attention.

“Through an arranged marriage, Krishnamacharya honored his guru's second request. Ancient yogis were renunciates, who lived in the forest without homes or families. But Krishnamacharya's guru wanted him to learn about family life and teach a yoga that benefited the modern householder. At first, this proved a difficult pathway. The couple lived in such deep poverty that Krishnamacharya wore a loincloth sewn of fabric torn from his spouse's sari. He would later recall this period as the hardest time of his life, but the hardships only steeled Krishnamacharya's boundless determination to teach yoga.

Developing Ashtanga Vinyasa

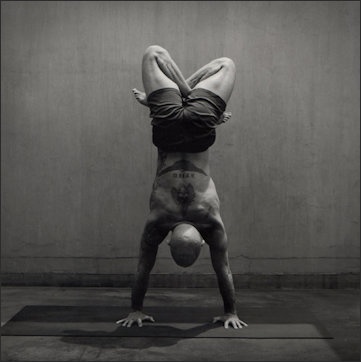

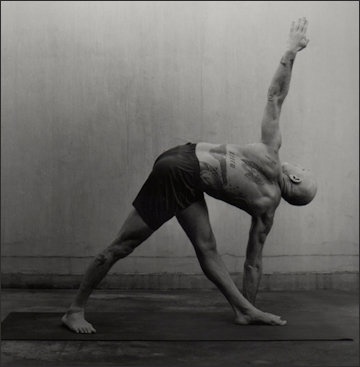

ashtanga yoga asana

Ruiz wrote in Yoga Journal: “Krishnamacharya's fortunes improved in 1931 when he received an invitation to teach at the Sanskrit College in Mysore. There he received a good salary and the chance to devote himself to teaching yoga full time. The ruling family of Mysore had long championed all manner of indigenous arts, supporting the reinvigoration of Indian culture. They had already patronized hatha yoga for more than a century, and their library housed one of the oldest illustrated asana compilations now known, the Sritattvanidhi (translated into English by Sanskrit scholar Norman E. Sjoman in The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“For the next two decades, the Maharaja of Mysore helped Krishnamacharya promote yoga throughout India, financing demonstrations and publications. A diabetic, the Maharaja felt especially drawn to the connection between yoga and healing, and Krishnamacharya devoted much of his time to developing this link. But Krishnamacharya's post at the Sanskrit College didn't last. He was far too strict a disciplinarian, his students complained. Since the Maharaja liked Krishnamacharya and didn't want to lose his friendship and counsel, he proposed a solution; he offered Krishnamacharya the palace's gymnastics hall as his own yogashala, or yoga school.

“Thus began one of Krishnamacharya's most fertile periods, during which he developed what is now known as Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga. As Krishnamacharya's pupils were primarily active young boys, he drew on many disciplines—including yoga, gymnastics, and Indian wrestling—to develop dynamically-performed asana sequences aimed at building physical fitness. This vinyasa style uses the movements of Surya Namaskar (Sun Salutation) to lead into each asana and then out again. Each movement is coordinated with prescribed breathing and drishti, "gaze points”that focus the eyes and instill meditative concentration. Eventually, Krishnamacharya standardized the pose sequences into three series consisting of primary, intermediate, and advanced asanas. Students were grouped in order of experience and ability, memorizing and mastering each sequence before advancing to the next.

Krishnamacharya and K. Pattabhi Jois

Ruiz wrote: “Though Krishnamacharya developed this manner of performing yoga during the 1930s, it remained virtually unknown in the West for almost 40 years. Recently, it's become one of the most popular styles of yoga, mostly due to the work of one of Krishnamacharya's most faithful and famous students,K. Pattabhi Jois. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

another ashtanga asana

“Pattabhi Jois met Krishnamacharya in the hard times before the Mysore years. As a robust boy of 12, Jois attended one of Krishnamacharya's lectures. Intrigued by the asana demonstration, Jois asked Krishnamacharya to teach him yoga. Lessons started the next day, hours before the school bell rang, and continued every morning for three years until Jois left home to attend the Sanskrit College. When Krishnamacharya received his teaching appointment at the college less than two years later, an overjoyed Pattabhi Jois resumed his yoga lessons.

“Jois retained a wealth of detail from his years of study with Krishnamacharya. For decades, he has preserved that work with great devotion, refining and inflecting the asana sequences without significant modification, much as a classical violinist might nuance the phrasing of a Mozart concerto without ever changing a note. Jois has often said that the concept of vinyasa came from an ancient text called the Yoga Kuruntha. Unfortunately, the text has disappeared; no one now living has seen it. So many stories exist of its discovery and content—I've heard at least five conflicting accounts—that some question its authenticity. When I asked Jois if he'd ever read the text, he answered, "No, only Krishnamacharya.”Jois then downplayed the importance of this scripture, indicating several other texts that also shaped the yoga he learned from Krishnamacharya, including the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Yoga Sutra, and the Bhagavad Gita.

“Whatever the roots of Ashtanga Vinyasa, today it's one of the most influential components of Krishnamacharya's legacy. Perhaps this method, originally designed for youngsters, provides our high-energy, outwardly-focused culture with an approachable gateway to a path of deeper spirituality. Over the last three decades a steadily increasing number of yogis have been drawn to its precision and intensity. Many of them have made the pilgrimage to Mysore, where Jois, himself, offered instruction until his death in May, 2009.

Krishnamacharya and Indra Devi

Ruiz wrote: “Even as Krishnamacharya taught the young men and boys at the Mysore Palace, his public demonstrations attracted a more diverse audience. He enjoyed the challenge of presenting yoga to people of different backgrounds. On the frequent tours he called "propaganda trips,”he introduced yoga to British soldiers, Muslim maharajas, and Indians of all religious beliefs. Krishnamacharya stressed that yoga could serve any creed and adjusted his approach to respect each student's faith. But while he bridged cultural, religious, and class differences, Krishnamacharya's attitude toward women remained patriarchal. Fate, however, played a trick on him: The first student to bring his yoga onto the world stage applied for instruction in a sari. And she was a Westerner to boot! [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“The woman, who became known as Indra Devi (she was born Zhenia Labunskaia, in pre-Soviet Latvia), was a friend of the Mysore royal family. After seeing one of Krishnamacharya's demonstrations, she asked for instruction. At first, Krishnamacharya refused to teach her. He told her that his school accepted neither foreigners nor women. But Devi persisted, persuading the Maharaja to prevail on his Brahmin. Reluctantly, Krishnamacharya started her lessons, subjecting her to strict dietary guidelines and a difficult schedule aimed at breaking her resolve. She met every challenge Krishnamacharya imposed, eventually becoming his good friend as well as an exemplary pupil.

“After a year-long apprenticeship, Krishnamacharya instructed Devi to become a yoga teacher. He asked her to bring a notebook, then spent several days dictating lessons on yoga instruction, diet, and pranayama. Drawing from this teaching, Devi eventually wrote the first best-selling book on hatha yoga, Forever Young, Forever Healthy. Over the years after her studies with Krishnamacharya, Devi founded the first school of yoga in Shanghai, China, where Madame Chiang Kai-Shek became her student. Eventually, by convincing Soviet leaders that yoga was not a religion, she even opened the doors to yoga in the Soviet Union, where it had been illegal. In 1947 she moved to the United States. Living in Hollywood, she became known as the "First Lady of Yoga,”attracting celebrity students like Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Arden, Greta Garbo, and Gloria Swanson. Thanks to Devi, Krishnamacharya's yoga enjoyed its first international vogue.

“Although she studied with Krishnamacharya during the Mysore period, the yoga Indra Devi came to teach bears little resemblance to Jois's Ashtanga Vinyasa. Foreshadowing the highly individualized yoga he would further develop in later years, Krishnamacharya taught Devi in a gentler fashion, accommodating but challenging her physical limitations.

“Devi retained this gentle tone in her teaching. Though her style didn't employ vinyasa, she used Krishnamacharya's principles of sequencing so that her classes expressed a deliberate journey, beginning with standing postures, progressing toward a central asana followed by complementary poses, then concluding with relaxation. As with Jois, Krishnamacharya taught her to combine pranayama and asana. Students in her lineage still perform each posture with prescribed breathing techniques.

“Devi added a devotional aspect to her work, which she calls Sai Yoga. The main pose of each class includes an invocation, so that the fulcrum of each practice involves a meditation in the form of an ecumenical prayer. Although she developed this concept on her own, it may have been present in embryonic form in the teachings she received from Krishnamacharya. In his later life, Krishnamacharya also recommended devotional chanting within asana practice.

“Though Devi died in April, 2002 at the age of 102, her six yoga schools are still active in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Until three years ago, she still taught asanas. Well into her nineties, she continued touring the world, bringing Krishnamacharya's influence to a large following throughout North and South America. Her impact in the United States waned when she moved to Argentina in 1985, but her prestige in Latin America extends well beyond the yoga community.

“You might be hard-pressed to find someone in Buenos Aires who doesn't know of her. She's touched every level of Latin society: The taxi driver who brought me to her house for an interview described her as "a very wise woman"; the next day, Argentina's President Menem came for her blessings and advice. Devi's six yoga schools deliver 15 asana classes daily, and graduates from the four-year teacher-training program receive an internationally recognized college-level degree.”

Krishnamacharya and B.K.S. Iyengar

B K S Iyengar

Ruiz wrote: “During the period when he was instructing Devi and Jois, Krishnamacharya also briefly taught a boy named B.K.S. Iyengar, who would grow up to play perhaps the most significant role of anyone in bringing hatha yoga to the West. It's hard to imagine how our yoga would look without Iyengar's contributions, especially his precisely detailed, systematic articulation of each asana, his research into therapeutic applications, and his multi-tiered, rigorous training system which has produced so many influential teachers. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“It's also hard to know just how much Krishnamacharya's training affected Iyengar's later development. Though intense, Iyengar's tenure with his teacher lasted barely a year. Along with the burning devotion to yoga he evoked in Iyengar, perhaps Krishnamacharya planted the seeds which were later to germinate into Iyengar's mature yoga. (Some of the characteristics for which Iyengar's yoga is noted—particularly, pose modifications and using yoga to heal—are quite similar to those Krishnamacharya developed in his later work.) Perhaps any deep inquiry into hatha yoga tends to produce parallel results. At any rate, Iyengar has always revered his childhood guru. He still says, "I'm a small model in yoga; my guruji was a great man."

“Iyengar's destiny wasn't apparent at first. When Krishnamacharya invited Iyengar into his household—Krishnamacharya's wife was Iyengar's sister—he predicted the stiff, sickly teenager would achieve no success in yoga. In fact, Iyengar's account of his life with Krishnamacharya sounds like a Dickens novel. Krishnamacharya could be an extremely harsh taskmaster. At first, he barely bothered to teach Iyengar, who spent his days watering the gardens and performing other chores. Iyengar's only friendship came from his roommate, a boy named Keshavamurthy, who happened to be Krishnamacharya's favorite protégé. In a strange twist of fate, Keshavamurthy disappeared one morning and never returned. Krishnamacharya was only days away from an important demonstration at the yogashala and was relying on his star pupil to perform asanas. Faced with this crisis, Krishnamacharya quickly began teaching Iyengar a series of difficult postures.

“Iyengar practiced diligently and, on the day of the demonstration, surprised Krishnamacharya by performing exceptionally. After this, Krishnamacharya began instructing his determined pupil in earnest. Iyengar progressed rapidly, beginning to assist classes at the yogashala and accompanying Krishnamacharya on yoga demonstration tours. But Krishnamacharya continued his authoritarian style of instruction. Once, when Krishnamacharya asked him to demonstrate Hanumanasana (a full split), Iyengar complained that he had never learned the pose. "Do it!”Krishnamacharya commanded. Iyengar complied, tearing his hamstrings.

“Iyengar's brief apprenticeship ended abruptly. After a yoga demonstration in northern Karnataka Province, a group of women asked Krishnamacharya for instruction. Krishnamacharya chose Iyengar, the youngest student with him, to lead the women in a segregated class, since men and women didn't study together in those days. Iyengar's teaching impressed them. At their request, Krishnamacharya assigned Iyengar to remain as their instructor.”

Hard Times for Krishnamacharya

Ruiz wrote: “Even as his students prospered and spread his yoga gospel, Krishnamacharya himself again encountered hard times. By 1947, enrollment had dwindled at the yogashala. According to Jois, only three students remained. Government patronage ended; India gained their independence and the politicians who replaced the royal family of Mysore had little interest in yoga. Krishnamacharya struggled to maintain the school, but in 1950 it closed. A 60-year-old yoga teacher, Krishnamacharya found himself in the difficult position of having to start over. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

Krishnamacharya teaching

“Unlike some of his protégés, Krishnamacharya didn't enjoy the perks of yoga's growing popularity. He continued to study, teach, and evolve his yoga in near obscurity. Iyengar speculates that this lonely period changed Krishnamacharya's disposition. As Iyengar sees it, Krishnamacharya could remain aloof under the protection of the Maharaja. But on his own, having to find private students, Krishnamacharya had more motivation to adapt to society and to develop greater compassion.

“As in the 1920s, Krishnamacharya struggled to find work, eventually leaving Mysore and accepting a teaching position at Vivekananda College in Chennai. New students slowly appeared, including people from all walks of life and in varying states of health, and Krishnamacharya discovered new ways to teach them. As students with less physical aptitude came, including some with disabilities, Krishnamacharya focused on adapting postures to each student's capacity. “For example, he would instruct one student to perform Paschimottanasana (Seated Forward Bend) with knees straight to stretch the hamstrings, while a stiffer student might learn the same posture with knees bent. Similarly, he'd vary the breath to meet a student's needs, sometimes strengthening the abdomen by emphasizing exhalation, other times supporting the back by emphasizing inhalation. Krishnamacharya varied the length, frequency, and sequencing of asanas to help students achieve specific short-term goals, like recovering from a disease. As a student's practice advanced, he would help them refine asanas toward the ideal form. In his own individual way, Krishnamacharya helped his students move from a yoga that adapted to their limitations to a yoga that stretched their abilities. This approach, which is now usually referred to as Viniyoga, became the hallmark of Krishnamacharya's teaching during his final decades.

“Krishnamacharya seemed willing to apply such techniques to almost any health challenge. Once, a doctor asked him to help a stroke victim. Krishnamacharya manipulated the patient's lifeless limbs into various postures, a kind of yogic physical therapy. As with so many of Krishnamacharya's students, the man's health improved—and so did Krishnamacharya's fame as a healer.”

T.K.V. Desikachar, Krishnamacharya’s Son, Keeps the Flame Alive

Ruiz wrote: ““It was this reputation as a healer that would attract Krishnamacharya's last major disciple. But at the time, no one—least of all Krishnamacharya—would have guessed that his son,T.K.V. Desikachar, would become a renowned yogi who would convey the entire scope of Krishnamacharya's career, and especially his later teachings, to the Western yoga world. Although born into a family of yogis, Desikachar felt no desire to pursue the vocation. As a child, he ran away when his father asked him to do asanas. Krishnamacharya caught him once, tied his hands and feet into Baddha Padmasana (Bound Lotus Pose), and left him tied up for half an hour. Pedagogy like this didn't motivate Desikachar to study yoga, but eventually inspiration came by other means. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

T V K Desikachar

“After graduating from college with a degree in engineering, Desikachar joined his family for a short visit. He was en route to Delhi, where he'd been offered a good job with a European firm. One morning, as Desikachar sat on the front step reading a newspaper, he spotted a hulking American car motoring up the narrow street in front of his father's home. Just then, Krishnamacharya stepped out of the house, wearing only a dhoti and the sacred markings that signified his lifelong devotion to the god Vishnu. The car stopped and a middle-aged, European-looking woman sprang from the backseat, shouting "Professor, Professor!”She dashed up to Krishnamacharya, threw her arms around him, and hugged him.

“The blood must have drained from Desikachar's face as his father hugged her right back. In those days, Western ladies and Brahmins just did not hug—especially not in the middle of the street, and especially not a Brahmin as observant as Krishnamacharya. When the woman left, "Why?!?”was all Desikachar could stammer. Krishnamacharya explained that the woman had been studying yoga with him. Thanks to Krishnamacharya's help, she had managed to fall asleep the previous evening without drugs for the first time in 20 years. Perhaps Desikachar's reaction to this revelation was providence or karma; certainly, this evidence of the power of yoga provided a curious epiphany that changed his life forever. In an instant, he resolved to learn what his father knew.

“Krishnamacharya didn't welcome his son's newfound interest in yoga. He told Desikachar to pursue his engineering career and leave yoga alone. Desikachar refused to listen. He rejected the Delhi job, found work at a local firm, and pestered his father for lessons. Eventually, Krishnamacharya relented. But to assure himself of his son's earnestness—or perhaps to discourage him—Krishnamacharya required Desikachar to begin lessons at 3:30 every morning. Desikachar agreed to submit to his father's requirements but insisted on one condition of his own: No God. A hard-nosed engineer, Desikachar thought he had no need for religion. Krishnamacharya respected this wish, and they began their lessons with asanas and chanting Patanjali's Yoga Sutra. Since they lived in a one-room apartment, the whole family was forced to join them, albeit half asleep. The lessons were to go on for 28 years, though not always quite so early.

“During the years of tutoring his son, Krishnamacharya continued to refine the Viniyoga approach, tailoring yoga methods for the sick, pregnant women, young children—and, of course, those seeking spiritual enlightenment. He came to divide yoga practice into three stages representing youth, middle, and old age: First, develop muscular power and flexibility; second, maintain health during the years of working and raising a family; finally, go beyond the physical practice to focus on God.

“Desikachar observed that, as students progressed, Krishnamacharya began stressing not just more advanced asanas but also the spiritual aspects of yoga. Desikachar realized that his father felt that every action should be an act of devotion, that every asana should lead toward inner calm. Similarly, Krishnamacharya's emphasis on the breath was meant to convey spiritual implications along with physiological benefits.

“According to Desikachar, Krishnamacharya described the cycle of breath as an act of surrender: "Inhale, and God approaches you. Hold the inhalation, and God remains with you. Exhale, and you approach God. Hold the exhalation, and surrender to God."

“During the last years of his life, Krishnamacharya introduced Vedic chanting into yoga practice, always adjusting the number of verses to match the time the student should hold the pose. This technique can help students maintain focus, and it also provides them with a step toward meditation. “When moving into the spiritual aspects of yoga, Krishnamacharya respected each student's cultural background. One of his longtime students, Patricia Miller, who now teaches in Washington, D.C., recalls him leading a meditation by offering alternatives. He instructed students to close their eyes and observe the space between the brows, and then said, "Think of God. If not God, the sun. If not the sun, your parents.”Krishnamacharya set only one condition, explains Miller: "That we acknowledge a power greater than ourselves."

Krishnamacharya’s Legacy

Ruiz wrote: “Today Desikachar extends his father's legacy by overseeing the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram in Chennai, India, where all of Krishnamacharya's contrasting approaches to yoga are being taught and his writings are translated and published. Over time, Desikachar embraced the full breadth of his father's teaching, including his veneration of God. But Desikachar also understands Western skepticism and stresses the need to strip yoga of its Hindu trappings so that it remains a vehicle for all people. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“Krishnamacharya's worldview was rooted in Vedic philosophy; the modern West's is rooted in science. Informed by both, Desikachar sees his role as translator, conveying his father's ancient wisdom to modern ears. The main focus of both Desikachar and his son, Kausthub, is sharing this ancient yoga wisdom with the generation. "We owe children a better future,”he says. His organization provides yoga classes for children, including the disabled. In addition to publishing age-appropriate stories and spiritual guides, Kausthub is developing videos to demonstrate techniques for teaching yoga to youngsters using methods inspired by his grandfather's work in Mysore.

“Although Desikachar spent nearly three decades as Krishnamacharya's pupil, he claims to have gleaned only the basics of his father's teachings. Both Krishnamacharya's interests and personality resembled a kaleidoscope; yoga was just a small part of what he knew. Krishnamacharya also pursued disciplines like philology, astrology, and music too. In his own Ayurvedic laboratory, he prepared herbal recipes.

“In India, he's still better known as a healer than as a yogi. He was also a gourmet cook, a horticulturist, and shrewd card player. But the encyclopedic learning that made him sometimes seem aloof or even arrogant in his youth—"intellectually intoxicated,”as Iyengar politely characterizes him—eventually gave way to a yearning for communication. Krishnamacharya realized that much of the traditional Indian learning he treasured was disappearing, so he opened his storehouse of knowledge to anyone with a healthy interest and sufficient discipline. He felt that yoga had to adapt to the modern world or vanish.

“An Indian maxim holds that every three centuries someone is born to re-energize a tradition. Perhaps Krishnamacharya was such an avatar. While he had enormous respect for the past, he also didn't hesitate to experiment and innovate. By developing and refining different approaches, he made yoga accessible to millions. That, in the end, is his greatest legacy. “As diverse as the practices in Krishnamacharya's different lineages have become, passion and faith in yoga remain their common heritage. The tacit message his teaching provides is that yoga is not a static tradition; it's a living, breathing art that grows constantly through each practitioner's experiments and deepening experience.

Krishna Pattabhi Jois

Pattabhi Jois

Krishna Pattabhi Jois (1914-2009) was a prominent and influential yoga teacher who drew a global following that included Western celebrities like Madonna, Gwyneth Paltrow and Sting. Known to his followers simply as guruji, a term of respect for teachers, Jois (pronounced JOYCE) was based in the southern Indian city of Mysore.

Vikas Bajaj wrote in the New York Times: “Long before yoga studios sprang up in shopping centers and gyms across America and Europe, Mr. Jois began teaching yoga at the Sanskrit University of Mysore in the late 1930s, according to a biography on his Web site. He eventually opened his own school, the Ashtanga Yoga Institute, which has drawn students from around the world. [Source: Vikas Bajaj, New York Times, May 20, 2009 ^^^]

“The son of a Brahmin priest and astrologer, Mr. Jois was inculcated in ancient Hindu teachings from an early age. He was first exposed to yoga when he was 12. He learned from Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, a guru who also taught another famous Indian yogi, B.K.S. Iyengar. Mr. Jois popularized the school of yoga known as Ashtanga, which literally means eight limbs and is characterized by fast-paced exercises that involve pronounced, but controlled, breathing while holding varying postures. Unlike some other forms of yoga, Ashtanga is meant to induce profuse sweating, which Mr. Jois said was necessary to cleanse the body. ^^^

“Though he enjoyed success and international acclaim in recent decades, Mr. Jois had a difficult early life. According to his biography, he left the village of Kowshika, in Karnataka State, with two friends and 2 rupees (about 4 cents at today’s exchange rates) when he was 14. He hoped to attend the Sanskrit University in Mysore, which is about 90 miles east of Bangalore. ^^^

“In a chance encounter, he reconnected with his yoga guru, Mr. Krishnamacharya. Later he met the ruler of Mysore, who made it possible for him to teach yoga at the Sanskrit University. While there, he married Savitramma, who died in 1997. They had three children, two of whom survive him: a son Manju, who lives in Encinitas, Calif., and a daughter, Saraswati, who lived with him in Mysore. His son Ramesh was killed in an accident. He is also survived by three grandchildren, including Mr. Rangaswamy, and four great-grandchildren. ^^^

“Mr. Jois’s following in the West brought him fame and influence, but people close to him say that it did not appear to have changed him much. He never altered his early morning prayer rituals and put all of his students, including the celebrities, through the same tough regimen, Mr. Rangaswamy said. “Everybody got the same training,” he said. “There was no difference.” ^^^

Krishnamacharya and K. Pattabhi Jois

ashtanga asana

Ruiz wrote: “Though Krishnamacharya developed this manner of performing yoga during the 1930s, it remained virtually unknown in the West for almost 40 years. Recently, it's become one of the most popular styles of yoga, mostly due to the work of one of Krishnamacharya's most faithful and famous students, K. Pattabhi Jois. [Source: Fernando Pagés Ruiz, Yoga Journal, August 29, 2007 ]

“Pattabhi Jois met Krishnamacharya in the hard times before the Mysore years. As a robust boy of 12, Jois attended one of Krishnamacharya's lectures. Intrigued by the asana demonstration, Jois asked Krishnamacharya to teach him yoga. Lessons started the next day, hours before the school bell rang, and continued every morning for three years until Jois left home to attend the Sanskrit College. When Krishnamacharya received his teaching appointment at the college less than two years later, an overjoyed Pattabhi Jois resumed his yoga lessons.

“Jois retained a wealth of detail from his years of study with Krishnamacharya. For decades, he has preserved that work with great devotion, refining and inflecting the asana sequences without significant modification, much as a classical violinist might nuance the phrasing of a Mozart concerto without ever changing a note. Jois has often said that the concept of vinyasa came from an ancient text called the Yoga Kuruntha. Unfortunately, the text has disappeared; no one now living has seen it. So many stories exist of its discovery and content—I've heard at least five conflicting accounts—that some question its authenticity. When I asked Jois if he'd ever read the text, he answered, "No, only Krishnamacharya.”Jois then downplayed the importance of this scripture, indicating several other texts that also shaped the yoga he learned from Krishnamacharya, including the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Yoga Sutra, and the Bhagavad Gita.

“Whatever the roots of Ashtanga Vinyasa, today it's one of the most influential components of Krishnamacharya's legacy. Perhaps this method, originally designed for youngsters, provides our high-energy, outwardly-focused culture with an approachable gateway to a path of deeper spirituality. Over the last three decades a steadily increasing number of yogis have been drawn to its precision and intensity. Many of them have made the pilgrimage to Mysore, where Jois, himself, offered instruction until his death in May, 2009.”

Yoga Class with Sri K. Pattabhi Jois in India

Describing a class by the then 84-year-old Sri K. Pattabhi Jois in Mysore, Rebecca Mead wrote in The New Yorker, “Jois doesn't teach in the manner of a Western aerobics class, by standing in the front of the room and yelling instructions. Instead each student shows up at an appointed time and works through the series of postures at his or her own place, while Jois, barrel-stomached in black Calvin Klein briefs and, and bare-chested except for his Brahmin stings performs what are known in the yoga business as adjustments — -winching a leg into place or leaning heavily on a student's back to stretch him or her further." [Source: Rebecca Mead The New Yorker, August 14, 2000 \=/]

ashtanga asana

“All the men are stripped to the waist, the women are in spandex, and all of them are slick with sweat as they twist their bodies in unimaginable knots or deep into breathtaking backbends, seeming to hang suspended in the air they jump from one position to the next...The room is silent but for the subtle chorus of long, repetitive, nasal hisses, and occasional pigeon English command from Jois, who barks, “Nooooo! You go down!...It is a serenity born of concentration and pain — -torture meets bliss." \=/

On her first 5:00am lesson Mead said that Jois “had alarmed me while I was attempting a forward bend by coming up behind me, grabbing my hips, and tipping me over so that my head hovered inches above the ground and my feet almost slipped out from under me: it's hard to think about meditating when the only thing preventing your head from crashing on the concrete floor is the physical strength of an octogenarian." Initiates often have castor oil smeared all their head an body, a process that is supposed make them more supple but often makes them physically sick. \=/

“At Jois's daily afternoon conference...students are invited to sit with him and ask questions about yoga theory and about his life...The atmosphere is more one of companionable comfort than pedagogical rigor: on many afternoons, Jois, who is known as Gurji, will settle in his chair in his tank top and dhoti...and immerse himself in the newspaper, while his students sit cross-legged in beatific silence at his feet." Most of the participants in Jois's classes are Westerners who engage in normal backbacker activities when they are not in the classes. Local Indians often have little time or little interest in yoga. Those that are interested in it are often in to it as way to make money from Westerners. \=/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 3 South Asia” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin; “A Guide to Angkor: an Introduction to the Temples” by Dawn Rooney (Asia Book) for Information on temples and architecture. National Geographic, the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018