BRITISH DURING THE BRITISH RAJ

Simla There were never really that many Britons in India. At the height of British imperialism in the 1930s, there were only 167,000 Europeans in all of South Asia. Britons in India were characterized by their English mother tongue, Christian religion, European lifestyle at home, Western clothes and employment in administration and service positions.

Journalist Jan Morris wrote in Newsweek, "Britons...on the other side of the world had come to think of India as part of their own national identity, a permanent presence in the public consciousness, at once exotic and familiar. Innumerable British families, of all social rank, had sent their representatives to India, as soldiers, as business people, as administrators, as ne'er-do-well younger sons or as pious missionaries."

The invention of the steam ship really opened up travel between Britain and India. The first run of the P&O steamer around the Cape of Good Hope took 91 days to travel from Southampton, England to Calcutta, with eight days spent taking in coal.

In 1876, the British parliament ruled that India should become an empire and Queen Victoria was named Empress. A viceroy ruled India. When King George VI (1936-53) visited India he was greeted as the King of England and the Emperor of India.

European perceptions of India, and those of the British especially, shifted from unequivocal appreciation to sweeping condemnation of India's past achievements and customs. Imbued with an ethnocentric sense of superiority, British intellectuals, including Christian missionaries, spearheaded a movement that sought to bring Western intellectual and technological innovations to Indians. Interpretations of the causes of India's cultural and spiritual "backwardness" varied, as did the solutions. Many argued that it was Europe's mission to civilize India and hold it as a trust until Indians proved themselves competent for self-rule. [Source: Library of Congress]

British Superiority

"As the British came to govern more and more of India," Pico Iyer wrote, "they developed an even stronger feeling of racial superiority, the spirit of paternalism carrying not only concern but all the condescension that the word can imply. The increased separation of the races intensified by the growing presence of upper-class British women on the subcontinent." With the presence of these more insular and perhaps most racist women, the British men partied less with their Indian friends and paid fewer courtesy calls on the local maharajas.”

One British woman wrote in 1809: "These [Indian] people, if they have the virtues of slaves, they have their vices also. They are cunning and incapable of truth; they disregard the imputation of lying and perjury and I would consider it folly not to protect them for their own interest."

The 1830s and 1840s was a period in which reformers like Thomas Babington Macaulay were intent on remaking and Westernizing India. In his book “Orientalism” the historian Edward Said has argued that British presence in India and other colonies was based on a sense of “otherness” rooted at least in part on racial superiority and strengthening the English identity and was “about powerful people imposing their will on less powerful people.”

In his book “Ornamentalism; How the British Saw Their Empire” the historian David Cannadine said the British empire had its roots in transplanting the British class system abroad not on racial pride and has argueed the whole thing was kind of as show. He wrote: the British Empire “was about antiquity and anachronism, tradition and honor, order and subordination; about glory and chivalry, horses and elephants, knights and peers, processions and ceremony, plumed hats and ermine robes; about chiefs and emirs, sultans and nawabs, viceroys and proconsuls; about thrones and crowns, dominion and hierarchy, ostentation and ornamentalism.”

Getting Rich in India

cholera

Members of the British upper-class were besides themselves that an upstart like Robert Clive—the "unpromising son of a penurious country gentlemen"—could spend a few years in India and amass more wealth than landowning families had accumulated in centuries of abusing peasant farmers. Among many upper class families in Britain, the eldest son was expected to run the family estate and the second eldest son was expected to go off to India to seek his fortune. [Source: Pico Iyer, Smithsonian magazine, January 1988]

Even 10-pound-a-year clerks in India had a good life. Expecting to make fortunes later in their careers as traders and merchant, they took out loans and lived a lavish lifestyle way beyond what they could have enjoyed at home. Generally they were only required to work between 9:00am and noon. The rest of the day was often spent napping, drinking, gambling, womanizing and smoking opium and hashish. Those that made money often did so by hiring cargo space on ships to ship goods like to textiles, spices, artifacts and opium to England.

After reports of the fortunes made by Clive and others filtered back to England, it seemed that everyone wanted a position in India. Bribes were paid to London officials to secure positions. The situation got so out of hand that, as one member of parliament put it, traders "rolling one after another; wave after wave; and there is nothing before the eyes of the natives but an endless hopeless prospect of new birds of prey and passage."

Traditional English society became so fed up with nouveau riche adventurers from India the word nabob (based on “nawab,” a local Indian ruler) was coined to describe them. Somerset Maugham who often wrote about Asia once said: "The type of person who did leave Great Britain for faraway posts had no particular tradition to uphold, as did the landed gentry. He was most times an incompetent, rank opportunist, or a trouble maker."

Enjoying the Good Life in India During the Raj

The British settlements in India were ruled by the British Governor-in-Council. These governors enjoyed a lifestyle that rivaled the Mughal emperors. State dinners featured 600 different dishes and numerous courses, each ushered in with a trumpet. When the governor of Bombay left his palace in 1700 he was carried in a palanquin escorted by 80 servants waving silver wands. One of these governor, Elihu Yale (Madras, 1687-92), used part of his fortune to start a small college in New Haven, Connecticut. [Source: Pico Iyer, Smithsonian magazine, January 1988]

British culture also found its way to India. The members of the newly formed Indian Civil Service were educated men of taste. "Where the rough and ready merchants of old had lived like local princelings," Iyer wrote, "the new arrivals preferred to live like well-heeled Britons. Tom-toms were gradually replaced by fife-and-drum corps, curries by English dishes and local clothes by the latest (or almost latest) London fashions. Country houses complete with tidy gardens began to spring up." There were also some interesting mergings of cultures. First class train compartments in the 1880s were outfit with hookahs and hashish. Servants fixed tea and shined boots.

Most of the British residents were male. With no English wives to tie them down, these Englishmen were fond of attending parties which featured food, drink, opium and fun with dancing girls who usually doubled as prostitutes. It was customary for unmarried British men to keep an Indian mistress-housekeeper who would also raise their children.

After the Suez canal opened in 1868, and travel was shorter and easier, married English men and their families became more common and more British women arrived and married the single English men. After that the British community became more self-sufficient and more insular and separated from the India community.

Good Life in Calcutta During the Raj

Calcutta became a British version of a Mughal palace. Civil servants were brought in on gilded palanquins with silver bells and embroidered curtains to Calcutta's theaters, where they watched English farces from private box with silk canopies. A typical bachelor in 1780 had 65 servants, and no soldier would go to battle without a steward, cook, housekeeper, washerman, a mistress and 15 servants who carried his bed, tent, luggage, wine, tables, live poultry and other necessities. [Source: Pico Iyer, Smithsonian magazine, January 1988]

The well-heeled English crowd would spend their morning going to the racetrack; their early afternoons napping in the sweltering heat; their late afternoon cruising the embankment in their carriages; and their evening playing card games and attending balls and dinner parties. Ice cream was delivered from Maine in clipper ships and unmarried girls from England were brought over in cool weather on what later was nicknamed the Fishing Fleet (unmarried returned Empties took the journey home).

Drinks were kept cool with ice made in a novel way. In the early 18th century Indians were able to make ice when the temperature was above freezing as a result of cooling evaporation. The water was poured into bowls in the ground where it froze as some of the water evaporated during the night. In 1828 over 120 tons of ice was produced in this fashion. The supply, which was stored in pits covered by thatch roofs, lasted more than six months.

Train passing Dudhsagar Falls

Disease and Life in India

Many Englishmen didn't last long enough to enjoy these fruits in a climate where "two monsoons was the age of a man." Many dropped dead in the first six months from cholera, malaria, heatstroke, small pox, cobra bites or accidents. Others wasted away more slowly from syphilis, exotic jungle diseases and doctors who treated cholera with a red hot iron on the heel. Bombay was known as the "burying ground of the English."

The average lifespan for an Englishman in India was 31, for an Englishwoman just 28. At one point six out of every seven officers was claimed by dysentery, typhoid, cholera or malaria. British soldiers were urged not to stay past a limit of two monsoons. One military doctor calculated that a soldier was five times more likely to die in India than in England.

Methods for treating and avoiding disease left a lot to be desired. The English didn't boil their water but insisted on wearing red flannel underwear even in the sweltering heat.

Hill Stations

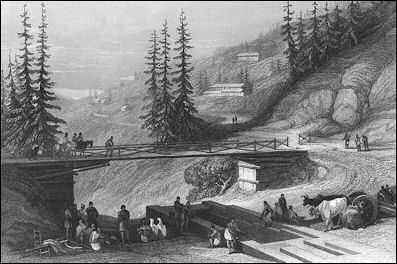

In the intense Indian summers, the English gentry and their servants fled the cities for the hill stations in the cooler mountains. The British built 96 hill stations in India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Burma. The Dutch built some in Indonesia, the French in Vietnam and the Americans in the Philippines. Most were built between 1820 and 1885. Simla, the largest hill station, was the capital of British India for most of the year and headquarters for the imperial army.

The first hill stations were built in 1820 after it was discovered that British soldiers fighting Gurhkas in the foothills of the Himalayas felt better and came down with less diseases in the high altitude than soldiers stationed at low altitudes.

The hill stations began as sanatoriums and convalescent centers, but it wasn’t long before they became places where healthy upper class people went to escape the heat of the lowland plains. Most of the hill stations were located above 6,000 feet because that seemed to be the ceiling of malaria-carrying mosquitos. Naturally cool air proved to be the perfect remedy for a world where air conditioning, insect repellant and antibiotics had not been invented.

Most hill stations were built on ridge tops. Now, while this had its advantages in fighting disease. It was not practical for supplying water, especially when trees were cut down and ground water levels drops. In the early days there were no scenic train rides. Visitors were brought up the slopes in bullock carts, on horseback, or in sedan chairs. A few walked.

Book: “Great Hill Stations of Asia” by Barbara Crossette (Harper Collins/ Westview, 1998)

Hill Station Life

The hill station were complete towns with sanitariums, churches, cottages, clubs, libraries and activities. Social activities went on almost around the clock and status and rank was rigidly defined. The hill stations were set up like towns back home. They featured comfortable cottages, steepled churches, clubs, schools, tearooms, and gardens with European flowers.

The atmosphere at the hill stations was both formal, strange and hedonistic. People attended full dress balls, drank a lot, slept in closed rooms to avoid the "miasma," indulged in extramarital affairs and had sex with prostitutes. One chronicler wrote, "I verily believe that when the white man penetrates the interior to found a colony, his first act is to clear a space and build a clubhouse."

One journalist described hill station life as "ball after ball, each followed by a little backbiting." Another said, "There is a theory that anyone who lives above 7,000 feet starts having delusions, illusions and hallucinations. People who, in the cities, are the models of respectability are known to fling more than stones and insults at each other when they come to live up here. “

Hill station residents lived quite well. Dinners often features a large selection of wines, ales and spirits, a choice of soups, fish, joints of Bengal mutton, Chinese capons, Keddah fowls, Sangora ducks, Yorkshire hams, Java potatoes and Malay ibis, rice, curry and fruit. Some Indians were invited. Describing the bejeweled maharajahs in Simla, Aldous Huxley wrote," At the Viceroy's evening parties the diamonds were so large they looked like stage gems. It was impossible to believe that pearls in the million-pound necklaces were the genuine excrement of oysters."

Missionaries in India

One consequence of the British sense of superiority was to open India to more aggressive missionary activity. The contributions of three missionaries based in Serampore (a Danish enclave in Bengal)— William Carey, Joshua Marshman, and William Ward— remained unequaled and have provided inspiration for future generations of their successors. The missionaries translated the Bible into the vernaculars, taught company officials local languages, and, after 1813, gained permission to proselytize in the company's territories. Although the actual number of converts remained negligible, except in rare instances when entire groups embraced Christianity, such as the Nayars in the south or the Nagas in the northeast, the missionary impact on India through publishing, schools, orphanages, vocational institutions, dispensaries, and hospitals was unmistakable. [Source: Library of Congress]

By the end of the 18th century, Hindus and Muslims were no longer regarded merely as novelties, they were seen as natives—like American Indians—that needed to converted to Christianity. In 1813 an anti-slavery activist told the British Parliament that he hoped India would "exchange its dark and bloody superstition for the genial influence of Christian light and good." Early Britons looked upon India as a backward society that could be improved through education. After Darwin many Britons began looking upon Indians as racially inferior.[Source: Geoffrey C. Ward, Smithsonian magazine]

Missionaries that came to India in large numbers beginning in the early 1800's endured numerous hardships and had little success converting the local population. Upon arrival many went to their boat cabins and wept with shock and prayed for strength after seeing throngs of sweaty Indians naked except for their loincloths.

Missionaries were often expected to live out their lives abroad and they were discouraged from coming home even if they were fatally ill. "It is better that our missionaries should die on the field of battle," one missionary board warned, "than to return to camp in a wounded or disabled state."

Life of the Missionaries

Missionary women were often carried about in palanquins resting on the shoulders of a half dozen Indian servants and the men were pulled in covered carts drawn by teams of bullocks. The journey from Madras to Madurui took 20 days by palanquin. As the servants carried the women they chanted “She's not heavy, “Putterum, Puuterum”, Carry her softly, “Puuterum, Putterum”, Nice little lady, “Puuterum, Putterum”, Carry her gently.” [Source: Geoffrey C. Ward, Smithsonian magazine]

The primary activity of missionaries was setting up schools. They usually set up numerous primary schools and, if they were there long enough to get primary school graduates, a secondary school. Low caste parents sent their children to the missionary schools because there was no other way for them to get an education. Hindus sent their children to the secondary school to learn English so they had better chances of getting jobs. Many Christian converts were Untouchables. They had more to gain from converting to Christianity than other Hindus.

Missionaries had to protect themselves against snakes, scorpions, white ants, winged ants and bats. One missionary described a huge spider that made a home in his shoe. It "was nearly the size of the palm of my hand...olive brown and covered with a soft down.” Many people died of malaria and deaths at a rate of 60 a day from cholera was not uncommon in some cities.

The missionaries also had to put up with dust storms, torrential monsoons and 130°F heat that lasted for weeks at a time. "Between the rising and setting of the sun," one missionary wrote, "a foreigner should not leave his house without the shelter of a carriage or palanquin or a thick umbrella."

Missionary View of the Indians

"View the gods of India," one missionary wrote, "false to their word, thievish, licentious, ambitious, murderous, all indeed that is repellent, malignant and vile...is it surprising that there is perjury, and injustice, and wickedness the land over? The Bible must supplant the narratives of their false divinities, their temples carved now with sculptures and paintings which crimson the face of modesty." [Source: Geoffrey C. Ward, Smithsonian magazine]

One missionary in Madurai in the 1830s described it as "a stronghold of debauchery. An influential and numerous priesthood dwell here...Tumultuous processions, wild and fantastic as the dreams of a maniac...pervade the city night and day, making idolaters drunk with excess of glare, noise and folly...all in barbarous taste." Missionaries were sometimes threatened with murder for maligning Hindu Gods.

In the19th century pounding and cleaning rice was "a constant employment among females." Street performers with trained monkeys were familiar sites and smiths spent hours beating gold. Irrigation pumps were powered by three men who were used as a counterweight. Some people earned money by mutilating themselves.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated June 2015