ASHOKA

Ashoka and his two queens at Sanchi

Emperor Asoka (born 304 B.C.,ruled 274-236 B.C.) was arguably the greatest ruler in Indian history and was the man who ensured Buddhism success as a world religion. After Asoka conquered the kingdom of Kalinga, in one of most important battles in the history of the world, near the Brubaneswar airport in the state of Orissa, he was so appalled by the number of people that were massacred (perhaps 100,000 or more) he converted himself and his kingdom to Buddhism and sent Buddhist missionaries to the four corners of Asia to spread the religion. The wheel Asoka used to symbolize his conversion to Buddhism is the same one pictured on India's flag today. H.G. Wells, a noted historian as well as science fiction writer, wrote: "Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history ... the name of Ashoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star."

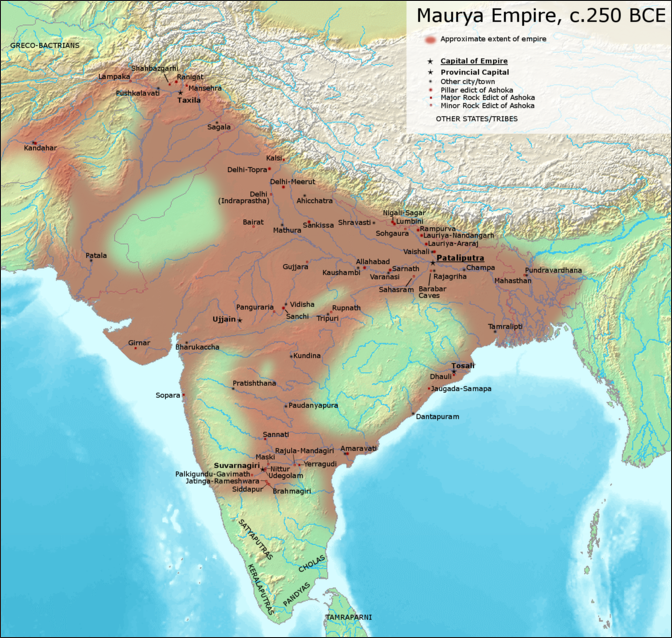

As the leader of the Maurya Empire Ashoka unified all of the subcontinent except the southern tip and put all of India under unified control for the first time. An early convert to Buddhism, his regime was remembered for its sectarian tolerance, as well as for remarkable administrative, legal, and cultural achievements. Under Ashoka, Buddhism was widely propagated and spread to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. Many Buddhist monuments and elaborately carved cave temples found at Sarnath, Ajanta, Bodhgaya, and other places in India date from the reigns of Ashoka and his Buddhist successors.

According to PBS: Ashoka “ruled over a territory stretching from the northern Himalayas into peninsular India and across the widest part of the subcontinent. Known for his principles of non-violence and religious tolerance, Ashoka modeled himself as a cakravartin, the Buddhist term for a "universal ruler," whose rule was based on the principle of dharma or conquest not by war but righteousness. To advance this principle, Ashoka had edicts based on the dharma carved on rocks, pillars, and caves throughout his kingdom and sent emissaries abroad to disseminate his views.” [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ The Mauryan emperor Ashoka (272–231 B.C.), a great military leader, conquered a large part of India. As a reaction to the horrors of war, he converted to Buddhism. To bring the Buddha’s teachings to his people, Ashoka built stupas throughout his kingdom. He also introduced a system of writing, which had been absent in India since the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization. When the Mauryan dynasty came to an end in the second century B.C., India was once again divided into smaller kingdoms. However, Buddhism continued to spread, and with it the building of stone stupas and meeting halls.[Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Religious Tolerance Page religioustolerance.org/buddhism ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; Buddhist Centre thebuddhistcentre.com; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org ; Victoria and Albert Museum vam.ac.uk/collections/asia/asia_features/buddhism/index

See Separate Article MAURYA EMPIRE factsanddetails.com ; ASHOKA’S EDICTS, PILLARS AND ROCKS factsanddetails.com

Ashoka and the Maurya Empire

Ashoka visiting Ramagrama stupa, from Sanchi Stupa 1 Southern gateway

The Maurya empire reached its zenith under Ashoka (273 and 232 B.C.)., who conquered most of the Indian subcontinent and then made Buddhism the state religion. The grandson of Chandragupta, Ashoka inscribed edicts Buddhist tenants on pillars throughout India, downplayed the caste system and tried to end expensive sacrificial rites.

According to PBS: His “exemplary story remains popular in folk plays and legends across southern Asia. The emperor ruled a vast territory that stretched from the Bay of Bengal to Kandahar and from the North-West Frontier of Pakistan to below the Krishna River in southern India. The year 261 B.C. marks a turning point in Ashoka's reign when, in part to increase access to the Ganges River, he conquered the east coast kingdom of Kalinga. By Ashoka's account, more than 250,000 people were killed, made captive or later died of starvation. Feeling remorseful about this massive suffering and loss, the emperor converted to Buddhism and made dharma, or dhamma, the central foundation of his personal and political life...To some historians, the edicts unified an extended empire, one that was organized into five parts governed by Ashoka and four governors. After his reign, Ashoka has become an enduring symbol of enlightened rule, non-violence, and religious tolerance. In 1950, the Lion Capital of Ashoka, a sandstone sculpture erected in 250 B.C., was adopted as India's official emblem by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

Ashoka and his predecessors and descendants created the largest ever Indian empire—stretching from present-day Myanmar (Burma) to Afghanistan and Sri Lanka. Ashoka is regarded as the first leader to conquer the world "in the name of religion and universal peace." Ashoka established a stable kingdom that lasted for over a hundred years and was supported by land taxes and trade duties, Trade expanded, agriculture produced bountiful harvests and new roads were buily to facilitate the movement of goods. One road extended all the way from Taxila in modern-day Pakistan to Tamralipti, the main port at the Ganges Delta.

Contacts established with the Hellenistic world during the reign of Ashoka's predecessors served him well. He sent diplomatic-cum-religious missions to the rulers of Syria, Macedonia, and Epirus, who learned about India's religious traditions, especially Buddhism. India's northwest retained many Persian cultural elements, which might explain Ashoka's rock inscriptions — such inscriptions were commonly associated with Persian rulers. Ashoka's Greek and Aramaic inscriptions found in Kandahar in Afghanistan may also reveal his desire to maintain ties with people outside of India. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ashoka and Spread of Buddhism

Under Ashoka, Buddhism was widely propagated and spread to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. Many Buddhist monuments and elaborately carved cave temples found at Sarnath, Ajanta, Bodhgaya, and other places in India date from the reigns of Ashoka and his Buddhist successors. Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to the four corners of Asia to spread the religion, led pilgrimages to all the Buddhist sacred places, repaired old shrines, “stupas” and built new ones. he was a tolerant ruler. He did not campaign against Brahmanism (Hinduism) he just derided some of the Hindu ceremonies and sacrifices as wasteful. To further the influence of dharma, he sent his son, a Buddhist monk, to Sri Lanka, and emissaries to countries including Greece and Syria.

The conversion process from Hinduism and Buddhism was easy in many places because Buddhism borrowed so many ideas and doctrines from Hinduism. When Asoka converted to Buddhism he simply changed Hindu stupas representing Mount Meru into Buddhist stupas that also represented Mt. Meru.

Buddhism appealed to merchants and took hold primarily in urban areas. Before its final decline in India, Buddhism developed the popular worship of enlightened beings (heavenly Bodhisattvas), produced a refined architecture (stupas or shrines) at Sanchi and sculpture (Gandharara reliefs 1-400 AD) on the geographical fringes of the Indian civilization. [Source: World Almanac]

Buddhism and Jainism had a profound impact on Indian and Hindu culture. They discouraged caste distinctions, abolished hereditary priesthoods, made poverty a precondition of spirituality and advocated the communion with the spiritual essence of the universe through contemplation and meditation.

See Separate Article: ASHOKA (304-236 B.C.) AND THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Ashoka’s Pillars and Edicts

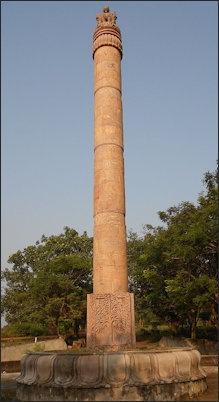

Ashoka placed rocks and stone pillars engraved with morally uplifting inscriptions on the sides of public roads to demarcate and define his kingdom. It was long thought they carried Buddhist messages but although some mentioned the idea of dharma they dealt mostly with the secular matters such as building wells, establishing rest houses for travelers, planting trees and founding medical services. Many of the commemorative stones pillars—at least 18 rocks and 30 stone pillars— he erected are still standing.

Ashoka’s inscriptions chiseled on rocks and stone pillars located at strategic locations throughout his empire — such as Lampaka (Laghman in modern Afghanistan), Mahastan (in modern Bangladesh), and Brahmagiri (in Karnataka) — constitute the second set of datable historical records. According to some of the inscriptions, in the aftermath of the carnage resulting from his campaign against the powerful kingdom of Kalinga (modern Orissa), Ashoka renounced bloodshed and pursued a policy of nonviolence or ahimsa, espousing a theory of rule by righteousness. His toleration for different religious beliefs and languages reflected the realities of India's regional pluralism although he personally seems to have followed Buddhism (see Buddhism). Early Buddhist stories assert that he convened a Buddhist council at his capital, regularly undertook tours within his realm, and sent Buddhist missionary ambassadors to Sri Lanka. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Throughout his kingdom, the emperor inscribed laws and injunctions inspired by dharma on rocks and pillars, some of them crowned with elaborate sculptures. Many of these edicts begin "Thus speaks Devanampiya Piyadassi [Beloved of the Gods]" and counsel good behavior including decency, piety, honoring parents and teachers and protection of the environment and natural world. Guided by this principle, Ashoka abolished practices that caused unnecessary suffering to men and animals and advanced religious toleration.

See Separate Article: ASHOKA’S EDICTS, PILLARS AND ROCKS factsanddetails.com

Ashoka’s Accession

The grandson of Chandragupta, Ashoka reportedly had to show he was willing to murder 99 rival brothers before he was allowed t claim the throne.

According to the Purdnas, Bindusara ruled for 25 years, whereas the Pali books assign to him a reign of 27 or 28 years. Assuming the correctness of the former, Bindusara must have died about 272 B.C., when he was succeeded by one of his sons, named Ashokavardhana or Ashoka, who had served his period of apprenticeship as Viceroy both at Taxila and Ujjain. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The Ceylonese accounts represent him ( Ashoka) as wading through a pool of blood to the throne, for he is said to have made short work of all his brothers, 99 in number, except his uterine brother, Tisya. This story is doubted by many scholars, who detect an allusion to the existence of his brothers in Rock Edict V. But, although the epigraphic evidence is inconclusive, as, it simply mentions Ashoka’s solicitude for the harems of his brothers, we may well believe that the Southern version is exaggerated. Presumably, the monks were interested in emphasising the dark background of his early career to show how A 4 oka, the monster of cruelty, was turned into the most gentle sovereign after he had come under the influence of the merciful teachings of the Buddha. This much, however, may be accepted as a fact that Ashoka had to reckon against his eldest brother, Susima or Sumana, before he could establish his claim to the throne. That the succession was disputed is also indicated by the interval of three or four years between Ashoka’s accession and coronation, which may, therefore, be dated circa 269 or 268 B.C.

Agam Kuan is an important archaeological site in Patna. Its name means unfathomable well and it is widely believed to be associated with Ashoka. It is said that the Agam Kuan was part of king Ashoka's hell chambers and used for purposes of torture. Apparently, fire used to emanate from the well and offenders were thrown into this fiery well. A legend says that it is the site where emperor Ashoka killed his 99 brothers by throwing them into the well. His aim was to be the master of the throne of the Mauryan empire. Devotees throw flowers and coins into this well as it is considered auspicious.

Ashoka’s Wives and Family

Various sources mention five consorts of Ashoka: Devi, Karuvaki, Asandhimitra, Padmavati, and Tishyarakshita). Kaurvaki is the only queen of Ashoka known from his own inscriptions: she is mentioned in an edict inscribed on a pillar at Allahabad. The inscription names her as the mother of prince Tivara, and orders the royal officers to record her religious and charitable donations. [Source: Wikipedia

According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka's chief queen was Asandhimitta, who died four years before him. It states that she was born as Ashoka's queen because in a previous life, she directed a pratyekabuddha to a honey merchant (who was later reborn as Ashoka). Some later texts also state that she additionally gave the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her. These texts say one day Ashoka mocked Asandhamitta was enjoying a tasty piece of sugarcane without having earned it through her karma. Asandhamitta replied that all her enjoyments resulted from merit resulting from her own karma. Ashoka then challenged her to prove this by procuring 60,000 robes as an offering for monks. At night, the guardian gods informed her about her past gift to the pratyekabuddha, and next day, she was able to miraculously procure the 60,000 robes. An impressed Ashoka makes her his favourite queen. , and even offers to make her a sovereign ruler. Asandhamitta refuses the offer, but still invokes the jealousy of Ashoka's 16,000 other wives. Ashoka proves her superiority by having 16,000 identical cakes baked with his royal seal hidden in only one of them. Each wife is asked to choose a cake, and only Asandhamitta gets the one with the royal seal. The Trai Bhumi Katha claims that it was Asandhamitta who encouraged her husband to become a Buddhist, and to construct 84,000 stupas and 84,000 viharas.

According to Mahavamsa, after Asandhamitta's death, Tissarakkha became the chief queen. The Ashokavadana does not mention Asandhamitta at all, but does mention Tissarakkha as Tishyarakshita. The Divyavadana mentions another queen called Padmavati, who was the mother of the crown-prince Kunala.

According to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka fell in love with Devi (or Vidisha-Mahadevi), as a prince in central India. After Ashoka's ascention to the throne, Devi chose to remain at Vidisha than move to the royal capital Pataliputra. According to the Mahavmsa, Ashoka's chief queen was Asandhamitta, not Devi: the text does not talk of any connection between the two women, so it is unlikely that Asandhamitta was another name for Devi. The Sri Lankan tradition uses the word samvasa to describe the relationship between Ashoka and Devi, which modern scholars variously interpret as sexual relations outside marriage, or co-residence as a married couple.

Tivara, the son of Ashoka and Karuvaki, is the only of Ashoka's sons to be mentioned by name in the inscriptions. According to North Indian tradition, Ashoka had a son named Kunala.[23] Kunala had a son named Samprati. The Sri Lankan tradition mentions a son called Mahinda, who was sent to Sri Lanka as a Buddhist missionary; this son is not mentioned at all in the North Indian tradition. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang states that Mahinda was Ashoka's younger brother (Vitashoka or Vigatashoka) rather than his illgetimate son. The Divyavadana mentions the crown-prince Kunala alias Dharmavivardhana, who was a son of queen Padmavati. According to Faxian, Dharmavivardhana was appointed as the governor of Gandhara. The Rajatarangini mentions Jalauka as a son of Ashoka. According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka had a daughter named Sanghamitta, who became a Buddhist nun.

Perry Garfinkel wrote in National Geographic: “As Buddhism migrated out of India, it took three routes. To the south, monks brought it by land and sea to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. To the north, they spread the word across Central Asia and along the Silk Road into China, from where it eventually made its way to Korea and Japan. A later wave took Buddhism over the Himalaya to Tibet. In all the countries, local customs and cosmologies were integrated with the Buddhist basics: the magic and masks of demon-fighting lamas in Tibet, the austerity of a Zen monk sitting still as a rock in a perfectly raked Japanese garden. Over centuries Buddhism developed an inclusive style, one reason it has endured so long and in such different cultures. People sometimes compare Buddhism to water: It is still, clear, transparent, and it takes the form and color of the vase into which it's poured.” [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005]

Battle of Kalinga

The Battle of Kalinga in the 260s B.C. was fought India between the Maurya Empire under Ashoka and the state of Kalinga, an independent feudal kingdom located on the east coast, in the present-day state of Odisha. It included one of the largest and bloodiest battles in Indian history. The conflict was the only major war Ashoka engaged in after his accession to the throne and the battle marked the close of empire building and military conquests of ancient India that began with Maurya king Bindusara. The death and destruction caused by the battle is said to have led to Ashoka decision to adopt Buddhism. [Source: Wikipedia]

The war was completed in the eighth year of Ashoka's reign, according to his own Edicts of Ashoka, probably in 262 B.C. The battle took place after a bloody battle for the throne following the death of his father, Ashoka prevailed and conquered Kalinga – but the consequences of the savagery changed Ashoka's views

According to PBS: “The Battle of Kalinga, an east coast kingdom in modern Orissa, marked a turning point in the rule of the Mauryan emperor, Ashoka the Great (c. 269–233 B.C.). In about 261 B.C., Ashoka fought a bloody war for the kingdom, a conquest he records in the thirteenth and most important of his Fourteen Rock Edicts. In the edict, he numbered the conflict's casualties and prisoners at more than 200,000 and expressed remorse for this massive loss of life and freedom. He renounced war for conquest through righteousness, dharma: "They should only consider conquest by dharma to be a true conquest, and delight in dharma should be their whole delight, for this is of value in both this world and the next." Dharma became the organizing principle of Ashoka's personal and public life and shaped his policies of non-violence and religious tolerance. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

Ramesh Prasad Mohapatra wrote in “Military History of Orissa”: “No war in the history of India as important either for its intensity or for its results as the Kalinga war of Ashoka. No wars in the annals of the human history has changed the heart of the victor from one of wanton cruelty to that of an exemplary piety as this one. From its fathomless womb the history of the world may find out only a few wars to its credit which may be equal to this war and not a single one that would be greater than this. The political history of mankind is really a history of wars and no war has ended with so successful a mission of the peace for the entire war-torn humanity as the war of Kalinga.”

Dhauligiri (or Dhauli, eight kilometers miles from Bhubaneswar) is where the Battle of Kalinga was fought. Situated by Daya Stream, the main attraction are the rock edicts and Peace Pagoda, or Dhauli Shanti Stupa, a large white stupa made in collaboration with the Japanese. From the top of the hill on which the stupa stands one can scan the famous battle field. On the rock there is an inscription of an elephant, the symbol of Buddha, reputedly placed there by Ashoka himself

Kalinga and the Background of the Battle

Kalinga is mentioned in the ancient scriptures as Kalinga the Braves (Kalinga Sahasikha). During the 3rd century B.C. the Greek ambassador Megasthenes in his tour of India had mentioned about the military strength of the Kalinga army of about one lakh which consisted of 60 thousand soldiers, 1700 horses and thousands of elephants. Kalinga was also powerful in the naval force. The vast military strength of Kalinga was the cause of jealousy for the Magadha empire. According to the historians the Magadha Emperor Ashoka invaded Kalinga in 261 B.C. Nearly one lakh soldiers lost their lives in the Kalinga War and one and half lakh soldiers were captured.

During Ashoka's invasion the capital of Kalinga was Toshali near Dhauli. The vast wealth, military power and the maritime activities of the Kalinga was the cause of jealousy for the Magadha empire. Though both Emperor Chandragupta Maurya and Bindusar wanted to conquer Kalinga, neither ventured a war with Kalinga.

After the death of Ashoka, the Great Kharavela became the emperor of Kalinga. He was the monarch of the Chedi Dynasty. The inscription found in the Elephant Caves of Khandagiri and Udaigiri mountains near Bhubaneswar describes in detail the reign of Emperor Kharavela.

Kalinga did not have a king at the time of the battle as it was culturally run without any. The reasons for invading Kalinga were both political and economic. Kalinga was a prosperous region consisting of peaceful and artistically skilled people. Known as the Utkala, they were the first from the region who traveled offshore to the southeast for trade. For that reason, Kalinga had important ports and a powerful navy. They had an open culture and used a uniform civil code.

Kalinga was under the rule of the Nanda Empire until the empire's fall in 321 B.C. Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta Maurya had previously attempted to conquer Kalinga, but had been repulsed. Ashoka set himself to the task of conquering the newly independent empire as soon as he felt he was securely established on the throne. Kalinga was a strategic threat to the Maurya empire. It could interrupt communications between Maurya capital Pataliputra and Maurya possessions in central Indian peninsula. Kalinga also controlled the coastline for the trade in bay of Bengal.

Impact of the Battle of Kalinga

Ashoka's Lion Pillar on the way to the Dhauli Giri

Ashoka was shocked by the bloodshed and felt that he was the cause of the destruction. The whole area of Kalinga was plundered and destroyed. Some of Ashoka's later edicts state that about 150,000 people died on the Kalinga side and an almost equal number of Ashoka's army, though legends among the Odia people – descendants of Kalinga's natives – claim that these figures were highly exaggerated by Ashoka. According to their legends, Kalinga armies caused twice the amount of destruction they suffered. Thousands of men and women were deported from Kalinga and forced to work on clearing wastelands for future settlement.

The war and led Ashoka to pledge to never again wage a war of conquest. Ashoka, Rock Edict No. 13 reads: “Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Priyadarsi, conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dharma, a love for the Dharma and for instruction in Dharma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.

The Battle of Kalinga prompted Ashoka, already a non-engaged Buddhist, to devote the rest of his life to ahimsa (non-violence) and to dharma-vijaya (victory through dharma). Following the conquest of Kalinga, Ashoka ended the military expansion of the empire and began an era of more than 40 years of relative peace, harmony, and prosperity.

The Battle of Kalinga took place during eighth year of Ashoka’s reign. Rama Shankar Tripathi wrote: “We have ventured the surmise elsewhere that the power of the Nandas extended to this region, and hence it must have asserted its independence in the confusion accompanying their overthrow, or during the disturbed reign of Bindusara. Thus, the task of recovering it fell to the lot of Ashoka. The Kalinga people offered stubborn resistance, for we learn from R. E. XIII that in the conflict no less than “one hundred and fifty thousand persons were captured, one hundred thousand were slain, and many times that number died,” perhaps of privation and pestilence. But nothing availed them, and their country was ruthlessly pillaged and conquered.” [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Extent of Ashoka’s Empire

It is well known that Kalinga was the only conquest of Ashoka. But he had inherited an enormous empire from his predecessors, and its limits may be fixed with tolerable accuracy. On the north-west, it certainly extended to the Hindu Kush, for there is every reason to believe that he retained the four satrapies of Aria (Herat), Arachosia (Kandahar), Gedrosia (Baluchistan), and Paropanisadas (Kabul valley), which were ceded to his grand-father by Selcukos Nikator. That Southern Afghanistan and the frontier regions continued to form part of Ashoka’s vast realm is clear from the findspots of his rock-edicts in Shahbazgarhi (Peshawar district) and Mansehra (Hazara district), as also from the evidence of Xuanzang who refers to the existence, of Ashokan Stupas in Kafiristan (Kapisa) and Jalalabad. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Further, the inclusion of Kashmir is deposed by the Chinese pilgrim, Xuanzang. It may be interesting to add here that the foundation of Srlnagar is ascribed to Ashoka, who is also credited with having built numerous Stupas and Caitjas in the valley. The inscriptions of Ashoka at Girnar and Sopara (Thana district) definitively point to his jurisdiction over Saurastra and the south-western regions. Besides, we also know from the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman that Yavanaraja Tusaspa 1 was Ashoka’s Viceroy in Saurastra.

In the north, Ashoka’s authority extended up to the Himalaya mountains. This is apparent from his edicts, which have been found at Kalsi (Dchradun district), Rummindei and Nigliva (Nepalese Tarai). Tradition also attributes to Ashoka the foundation of Lalitapatart in Nepal, where he went with his daughter Carumatl and her husband Devapala Ksatriya.

Eastwards, Bengal was comprised within his empire. Xuanzang noticed several Ashokan Stupas in the different parts of Bengal, and according to legends Ashoka went as far as Tamralipti (Tamluk) to see his son and daughter off to Ceylon. Kalinga, which was the only conquest of the Emperor, was, of course, included. Here he got two edicts inscribed — one at Dhauli (Puri district) and the other at Jaugada (Ganjam district). The inclusion of Bengal in the Mauryan Empire further receives some confirmation from the Mahasthan (Bogra district) Pillar Inscription, engraved in Brahmi characters of the Mauryan period.

Towards the south, Ashoka’s rock inscriptions have been discovered in Maski and Iragudi in the Nizam’s dominions, and Chitaldroog district in Mysore. Beyond this, there were the independent kingdoms of the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, and the Keralaputras (R. E. if).

Lastly, the edicts contain references to some of the towns 6f the empire, viz,, Bodhgaya, Taksasila (Taxila), Tosali, Samapa, Ujjayini, Suvarnagiri (Songir or Kanakagiri), Isila, Kau6ambi, Pataliputra. All these evidences indicate that the empire extended from the Hindu-Kush in the north-west to Bengal in the east; and from the foot of the mountains in the north to the Chitaldroog district in the south. It also comprised the two extremities of Kalinga and Saurastra. Indeed, it was of such imposing dimensions that Ashoka was fully justified in saying “mahalake hi vijitam”, i.e., “vast is my empire” (R. E. XIV). No king in ancient India was ever master of such extensive territories.

Government and Society Under Ashoka

The administrative system under Ashoka remained more or less the same as in the time of Chandragupta Maurya. It was an absolute benevolent monarchy, and Ashoka laid special stress upon the paternal principle of government. In the second Kalinga Edict he says: “All men are my children, and just as I desire for my children that they may enjoy every kind of prosperity and happiness both in this world and in the next, so also do I desire the same for all men.” As before, there was a council of Ministers (Parisad) to advise and help the Emperor in the business of the state (R. E. Ill and VI). [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Ashoka continued also the system of Provincial Administration. The important provinces were each under a prince of the blood royal (Kumara). We learn from the edicts that Taxila, Ujjayini, Tosali (Dhauli), and Suvarnagiri (Songir) were such scats of viceroyalty during Ashoka’s reign. Sometimes, however, trusted feudatory chiefs were appointed to the exalted viceregal offices, as is proved by the case of Raja Tusaspa, the Yavana, who had his capital at Girnar. Presumably, the Viceroys had their own ministers (. Amaiyas). At any rate, it was against the latter that the people of Taxila revolted in the time of Bindusara. The minor provinces were under governors, perhaps the Rajukas of the edicts.

Ashoka introduced a number of administrative innovations for good governance. He created the new office of Dbamma-Mabamdtas for the temporal and spiritual weal of his subjects. They were to look after the interests of the different religious groups and the distribution of charities, and also to mitigate the rigours of justice by securing reduction in penalties or release from imprisonment on the ground of age or numerous progeny, and by preventing any undue harassment. He allowed the Vativedakas (Reporters) to inform him about urgent public matters at all times wherever he may be (R.E. VI). Ashoka granted to the Rajukas, “set over many hundred thousands of people”, independence in the award of honours and punishments datnde) in order that they might discharge their duties confidently and fearlessly. They were, however, expected to maintain uniformity in penalties as well as in judicial procedure. Lastly, the Emperor released prisoners on the anniversary of his coronation (P.E. V), and gave three days’ respite to those sentenced to death (P.E. IV).

We get some glimpses of society as constituted in Ashoka’s time. It comprised religious orders like the Brahmanas, Sramanas, and other Pasandas, among which the Ajlvikas and the Nirgranthas (Jains) were the most prominent. These monks and ascetics spread the truth as they conceived it, and promoted the cause of learning by instruction and discussion. Besides, there were the householders and curiously the edicts mention all the four divisions, viz., Brahmanas; soldiers and their chiefs, corresponding to Ksatriyas; Ibhyas or Vaisyas; and slaves and servants, i.e., Sudras. The people were wont to perform many ceremonies to bring them good luck, and they believed in the hereafter. Meat-eating must have undoubtedly been a common feature of society, as appears from the comprehensive regulations laid down by Ashoka for preventing slaughter of animals (P.E. V). The “upper ten” perhaps practised polygamy, if the case of Ashoka himself furnishes any analogy. The references to harems in R.E. V would show that the segregation and restrictions upon the freedom of women-folk were then not unknown. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Ashoka’s Achievements and Reforms

His achievements were not only his victories of “Dharma”, but also on his achievements in the domain of art and architecture. Tradition credits him with the foundation of two cities, Srinagar in Kashmir and Lalitpur (the third largest city of Nepal after Kathmandu and Pokhara). . He also made, as noted by Faxian, considerable additions to the grandeur of his palace and the metropolis. He built a large number of Stupas throughout his far-flung empire to enshrine the corporeal relics of the Buddha. After the cremation of the Buddha’s remains his ashes were shared by eight claimants, who each raised a Stupa over them. These were opened by Ashoka, and, as the legend goes, he re-distributed the relics among 84,000 Stupas, which he himself built for the purpose. In addition, Ashoka undertook the construction of Viharas or monasteries and cave-dwellings for the residence of monks. Unfortunately, however, the extant evidence of his building activities is very scanty. [Source:“History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Ven. S. Dhammika wrote: The judicial system was reformed in order to make it more fair, less harsh and less open to abuse, while those sentenced to death were given a stay of execution to prepare appeals and regular amnesties were given to prisoners. State resources were used for useful public works like the importation and cultivation of medical herbs, the building of rest houses, the digging of wells at regular intervals along main roads and the planting of fruit and shade trees. To ensue that these reforms and projects were carried out, Ashoka made himself more accessible to his subjects by going on frequent inspection tours and he expected his district officers to follow his example. To the same end, he gave orders that important state business or petitions were never to be kept from him no matter what he was doing at the time. The state had a responsibility not just to protect and promote the welfare of its people but also its wildlife. Hunting certain species of wild animals was banned, forest and wildlife reserves were established and cruelty to domestic and wild animals was prohibited. The protection of all religions, their promotion and the fostering of harmony between them, was also seen as one of the duties of the state. It even seems that something like a Department of Religious Affairs was established with officers called dharma Mahamatras whose job it was to look after the affairs of various religious bodies and to encourage the practice of religion. [Source: “Edicts of King Ashoka: An English Rendering” by Ven. S. Dhammika, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy Sri Lanka, 1993]

Tolerance of Religion in Ashoka’s Empire

Asoka lions “Though Ashoka had himself embraced Buddhism, he was by no means an intolerant zealot. On the contrary, he bestowed due honours and patronage on all the sects then prevailing. He granted cavedwellings to the Ajivikas, and inculcated the virtues of liberality and seemly behaviour towards the votaries of different creeds — Brahmanas, Sramanas, Nirgranthas, etc. He believed that the followers of all sects aimed at “restraint of passions and purity of heart,” and, therefore, he desired that they should reside everywhere in his empire (R. E. VII). Above all, he exhorted his subjects to exercise self-control, be “bahuSruta,” i.e., have much information about the doctrines of different sects, and avoid disparaging any faith merely from attachment to one’s own, so that there may be a growth in mutual reverence and toleration (R. E. XII). Truly, these are lofty sentiments, which may bring solace even to the modern distracted world. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Owing to this catholicity Ashoka did not seek to impose his personal religion upon the people. Indeed, nowhere in his edicts does he mention the chief characteristics of Buddhism, to wit, the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, and the goal of Nirvana. The “Dharma”, which he presents to the world is, so to say, the essence or sara of all religions. He prescribes a code of conduct with a view to making life happier and purer. He laid great stress on obedience and respect for parents, preceptors, and elders. Liberality and proper treatment of Brahmanas, relations, friends, the aged, and the distressed, were highly commended. Ashoka defines the “Dharma” as comprising charity, compassion, truthfulness, purity, saintliness. self-control, gratitude, steadfastness, and so on. Negatively, it is freedom from sin, which is the outcome of anger, cruelty, pride), and jealousy. These ate points common to all religions, and so Ashoka can hardly be accused of utilising his vast resources as sovereign in the interests of any particular creed. To him, therefore, goes the credit of first conceiving the idea of a universal religion, synonymous with Duty in its broadest sense. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

Ashoka did not, however, give to all the current religious practices and beliefs the stamp of his recognition. In pursuance of the principle of non-injury to sentient beings, he did not hesitate to suppress entirely the performance of sacrifices accompanied with the slaughter of animals (R. E. I). This may have meant a real hardship to some of his people, who believed in their efficacy, but Ashoka was not prepared to make any compromise on this cardinal doctrine. He also condemned certain ceremonies as trivial, vulgar, and worthless. Mostly they were performed by womenfolk on occasions of births, deaths, marriages, journeys, etc. According to Ashoka, true ceremonial consisted of proper conduct in all relations of life. Similarly, he tried to change the popular idea of gifts and conquests. He declares that there is no such gift as dharma-d&na, which consists of “proper treatment of slaves and servants, obedience to mother and father, liberality to friends, companions, relations, Brahmana and Sramana ascetics, and abstention from slaughter of living creatures for sacrifice”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2020